Abstract

Kimura disease (KD) affecting an unusual site is a diagnostic challenge. We report herein the case of a 62-year-old Japanese woman who presented with swelling of the epiglottis, resulting in airway narrowing. Microscopically, biopsied and resected specimens both revealed lymphoid proliferation of a reactive immunophenotype, accompanied by vascular proliferation, eosinophilic infiltration, and stromal sclerosis. Adjunctive immunohistochemistry with immunoglobulin E in addition to laboratory and histological findings led us to seriously consider a diagnosis of KD. The patient underwent surgical removal with postoperative steroid therapy and has no evidence of recurrence. Our experience suggests that KD is potentially fatal as well as showing difficulty in the histological diagnosis when occurring in the upper respiratory tract, such as the epiglottis. A literature review disclosed that our case is the 11th case so far reported in this location, and that KD of the epiglottis did not show any male preponderance, as seen in other places.

Keywords: Kimura disease, Epiglottis, Respiratory tract

Introduction

Kimura disease (KD) is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, and usually presents as a subcutaneous mass in the head and neck region or the major salivary glands of young to middle-aged Asian men. It is often associated with regional lymphadenopathy. Elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and peripheral blood eosinophilia are also common. The histology of the lesion is characterized by dense lymphoid infiltrates containing prominent germinal centers, eosinophilic infiltrates, proliferation of postcapillary venules, and sclerosis. Recently, we have experienced KD occurring in the epiglottis with symptoms of slight dysphonia and dysphagia. A literature review showed that involvement of the epiglottis is rare, and only 10 cases of KD centered around the epiglottis were found. Here, we report an additional case and briefly review KD involving the upper respiratory tract. Lastly, we would like to stress that its unusual location may cause some difficulty in making a diagnosis histologically and clinically, and that it could be potentially fatal if left untreated.

Clinical Summary

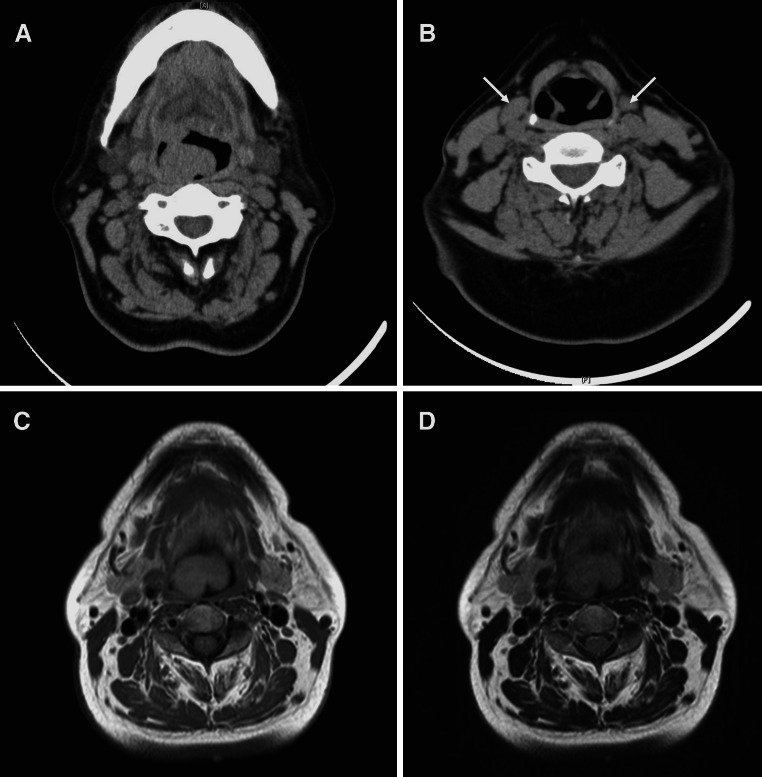

A 62-year-old Japanese woman, with a 3-month history of slight dysphonia and dysphagia, was found to have swelling of the epiglottis and anterior aspect of the right aryepiglottic fold with a smooth mucosal surface (Fig. 1). The tumor was 2.7 × 2.0 × 1.7 cm. Laboratory investigations showed elevated serum IgE at 467 IU/l (normal range <100 IU/l) and peripheral eosinophil count of 7.4 %, that was slightly increasing (normal range 1–6 %). Soluble interleukin-2 receptor at 386 U/ml was within the normal range (122–496 U/ml). Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a thickening of the epiglottis and the right aryepiglottic fold (Fig. 2a), and multiple cervical lymph node enlargement, each measuring up to 1 cm across (Fig. 2b). T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) depicted a homogenously hyperintense mass in the epiglottis and the right aryepiglottic fold (Fig. 2c, d). Malignancy, including lymphoma or carcinoma, was clinically suspected. Out of fear of airway obstruction, a tracheotomy was performed in our hospital with a biopsy of the lesion. The diagnosis of KD was considered based on the histological and laboratory findings, but initially hesitated because of its rarity in this location and the progressive clinical course. Under a possible diagnosis of KD, we performed a wide resection for more precise evaluation and the diagnosis was confirmed. The patient has been on low dose corticosteroid for 32 months and remains free of recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic view showing a mass-like swelling of the epiglottis about to obstruct the airway

Fig. 2.

CT showing a mass-like thickening of the epiglottis (a), and multiple cervical lymph node enlargement (b). T1-weighted (c) and T2-weighted (d) MRI displaying a homogenously hyperintense mass in the epiglottis

Pathological Findings

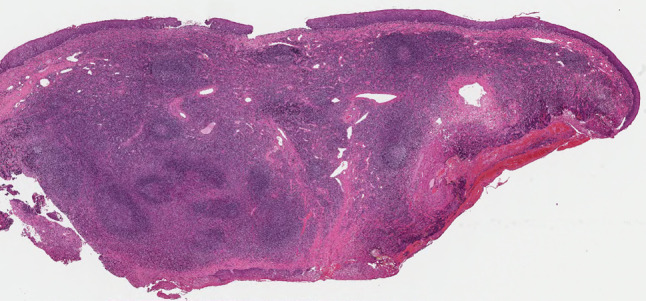

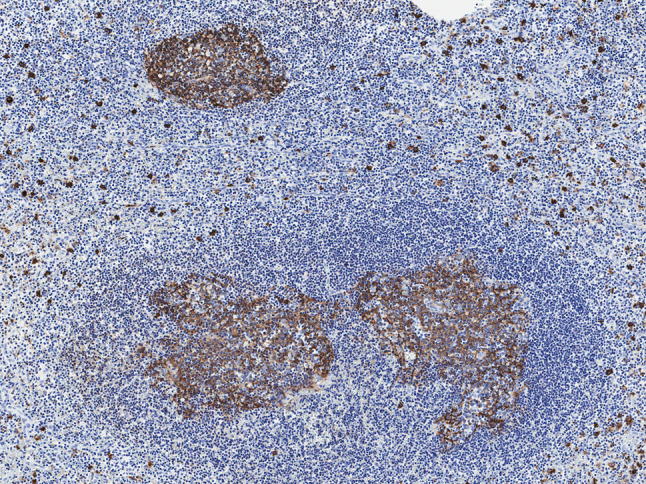

Histologically, the first biopsy specimen showed a non-specific chronic inflammatory change, except for mildly increased eosinophils. The second resected specimen was essentially similar but demonstrated vaguely nodular dense lymphoid aggregates with formation of follicles and germinal centers beneath the intact stratified squamous epithelium of the epiglottis, accompanied by vascular proliferation and numerous eosinophilic infiltrates within and around the lymphoid follicles, as well as stromal sclerosis (Figs. 3, 4, 5). CD138-positive plasma cells and CD117-positive mast cells were also intermingled. In some germinal centers, proteinaceous deposits could be observed (Fig. 6). Proliferating blood vessels were lined by swollen but conventional endothelium, without an epithelioid cell appearance. Immunohistochemical examination with IgE revealed characteristic reticular staining in germinal centers, identical to the distribution of follicular dendritic cells (Fig. 7). The immunophenotypical findings of lymphoid proliferation supported the reactive nature. These clinical and histological findings were considered compatible with KD, despite the unconventionality of the site involved.

Fig. 3.

Resected specimen showing submucosal nodular lymphoid aggregates containing follicles and germinal centers with sclerotic stroma (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×20)

Fig. 4.

Increased vessels and inflammatory infiltrates within and around the lymphoid follicles (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×50)

Fig. 5.

Increased vessels and prominent eosinophils (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×400)

Fig. 6.

Proteinaceous deposits in a germinal center (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×400)

Fig. 7.

Germinal centers showing reticular staining of IgE and surrounding IgE-positive mast cells (original magnification ×100)

Discussion

Kimura disease is endemic in Asia, and therefore many cases have been collected and reviewed in Asian countries [1–3], while it occurs only infrequently in non-Asian populations [4]. In general, KD tends to affect young adults, with patient age ranging from 1 to 72 years, with a mean age of 32.8 years, and shows a striking male predilection (M:F = 5:1). A subcutaneous mass in the head and neck region or a mass in the major salivary glands is the usual presentation, often being associated with regional lymphadenopathy [1–6]. Occasionally, lymph node enlargement is the only manifestation. The treatment for KD includes surgical excision, steroid therapy, and radiation. Although recurrences are common, the disease usually follows a benign clinical course. Other sites such as the oral cavity, axilla, groin, limbs, and trunk have also been described, but the involvement of the respiratory tract is rare. To our knowledge, 10 cases of KD centered around the epiglottis have appeared in the English and Japanese literature [7–16]. Our case provides an additional example (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of Kimura disease around the epiglottis

| Case [Ref.] | Age/Sex Race |

Site | Symptoms | Blood eosinophils (%) | Serum IgE (IU/l) | Treatment | FU (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [7] |

61/F Japanese |

Epiglottis Rt. preauricular mass |

Abnormal feeling in the larynx | 18 | 595 | Oral steroids | PD |

| 2 [8] |

15/M Korean |

Epiglottis Cervical LN |

Stridor during sleeping and dysphagia | 17.5 | 375 |

Surgery Oral steroids |

FD (1) |

| 3 [9] |

14/M Japanese |

Bi. false vocal cords Cervical LN |

Sleep apnea | 16.4 | 1260 |

Surgery Oral steroids Pranlukast |

FD |

| 4 [10] |

72/F Japanese |

Epiglottis | Abnormal feeling in the larynx | 9.7 | 797 |

Oral steroids Herbal medicine “Saibokutoh” |

FD (31) |

| 5 [11] |

41/M Turkish |

Paraglottic space | Voice hoarsening | NA | NA | Surgery | FD (6) |

| 6 [12] |

21/M Japanese |

Epiglottic vallecula Bi. parotid glands Cervical LN |

NA | 59.5 | 652 |

Surgery Oral steroids |

Rec. (24) |

| 7 [13] |

37/F Arabic |

Epiglottis | Difficulty in breathing and swallowing | 9 | NA | Surgery | Lost |

| 8 [14] |

45/M Japanese |

Epiglottis Lt. parotid gland Lt. lacrymal gland |

Asymptomatic | 32.9 | NA | Tranilast | PD (24) |

| 9 [15] |

52/F Japanese |

Epiglottis | Sensation of a foreign body in the pharynx | 12.5 | NA | Surgery | PD (24) |

| 10 [16] |

12/M Singaporean |

Epiglottis Cervical LN |

Asymptomatic | 11 | NA | Surgery | FD |

| 11 [Our case] |

62/F Japanese |

Epiglottis Cervical LN |

Dysphonia and dysphagia | 7.4 | 467 |

Surgery Oral steroids |

FD (32) |

FD free of disease, FU follow-up, LN lymph node, NA not available, PD persistent disease, Rec. recurrence

Among 10 cases that appeared in the literature as epiglottic KDs and our own case, there were six males and five females, thereby showing no apparent male predilection in these cases. Their ages ranged from 12 to 72 years, with a mean age of 39.2 years, which was in line with cases involving the usual sites. The symptoms were mostly related to airway narrowing, although two patients were asymptomatic. Because of symptoms related to respiratory problems, patients seem to have consulted doctors earlier, and eight cases were treated by surgery, five of whom became free of disease, one recurred but was free of disease after additional steroid therapy, one persisted, and one was lost follow-up. In contrast, two out of three patients treated by oral steroid alone or with other medications suffered persistent disease. In all cases, none of the patients died of the disease after treatment, but if untreated it may be fatal because of its location. Therefore, we believe that treatment is necessary and that the surgery seems most effective, and steroids are also beneficial to some extent.

Histology of KD may vary among cases and among locations in the same case. It characteristically consists of cellular (increased eosinophils and follicular hyperplasia), fibrocollagenous, and vascular (proliferation of the postcapillary venule) components. Other features include eosinophilic microabscesses, eosinophilic folliculolysis, germinal center (GC) necrosis, proteinaceous deposits in GC, polykaryocytes of the Warthin-Finkeldey type within GC, and IgE reticular staining in GC [1, 2, 4]. Findings may be basically non-specific and may cause some difficulty in making a histological diagnosis, particularly when the tissue sample is small, such as when obtained by biopsy. Histological differential diagnosis of KD may include angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL), Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), florid follicular hyperplasia, Castleman disease (CD), dermatopathic lymphadenopathy (DL), sinonasal eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis (EAF), drug reaction, parasitic reaction and others. Although KD has been confused and sometimes used synonymously with ALHE, it is now thought that these are entirely different entities [2, 5]. KD differs from ALHE in that the lymphoid component eclipses the minor vascular component and lacks the epithelioid endothelial cells that are the morphologic hallmark of ALHE. KD can be distinguished from HL by the absence of Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells and its variants, and from AITL by neoplastic clear cells. The absence of proliferative Langerhans cells that have distinctive cytologic features can exclude a diagnosis of LCH. Florid follicular hyperplasia shows proliferation of the postcapillary venule, proteinaceous deposits in GC, polykaryocytes, but lacks eosinophilia. The follicle in CD of the hyaline-vascular variant has atrophic germinal centers and tight concentric layering of the mantle zone, and a sclerotic blood vessel radially penetrates the germinal center, resulting in a “lollipop lesion”. CD of the plasma cell variant is characterized by diffuse plasma cell proliferation in the interfollicular area. Both variants of CD also lack eosinophilia. DL is distinguished by deposits of hemosiderin, melanin, and lipids, and KD usually does not show paracortical expansion by nodular proliferation of interdigitating dendritic cells and Langerhans cells, characteristics of DL. EAF lacks dense lymphoid aggregates with prominent germinal centers, and shows characteristic angiocentric whorled fibrosis. A careful clinical correlation helps in distinguishing KD from drug and parasitic reactions. Immunohistochemical analysis is also required to confirm the diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of KD remains unclear, but an immunologically-mediated mechanism has been suggested, based on the laboratory and histological findings. We suppose that air-borne and dietary agents may have a higher proportion among the etiological factors, because of the absence of gender predilection and the presence in the vicinity of the throat.

In summary, we report a case of KD involving the epiglottis. A review of the literature disclosed that it is rare and that males and females are equally affected in comparison with general male predominance. Rarity in this location may hinder a pathological diagnosis, so it is important to consider and include the possibility of KD in the differential diagnosis whenever chronic inflammatory conditions with germinal centers are seen with increased eosinophils in particular.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest and funding disclosures.

References

- 1.Hui PK, Chan JK, Ng CS, Kung IT, Gwi E. Lymphadenopathy of Kimura’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13(3):177–186. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urabe A, Tsuneyoshi M, Enjoji M. Epithelioid hemangioma versus Kimura’s disease. A comparative clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11(10):758–766. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198710000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu X, Fu J, Fang Y, Liang L. Kimura disease in children: a case report and a summary of the literature in Chinese. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(4):306–311. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181fce3b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Thompson LD, Aguilera NS, Abbondanzo SL. Kimura disease: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(4):505–513. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helander SD, Peters MS, Kuo TT, Su WP. Kimura’s disease and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: new observations from immunohistochemical studies of lymphocyte markers, endothelial antigens, and granulocyte proteins. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22(4):319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang JZ, Zhang CG, Chen JM. Thirty-five cases of Kimura’s disease (eosinophilic lymphogranuloma) Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(3):542–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi N, Kawamoto K, Takeuchi Y. Eosinophilic granuloma of the soft tissue (Kimura’s disease) on the epiglottis. Practica Otologica. 1995;41(2):157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho MS, Kim ES, Kim HJ, Yang WI. Kimura’s disease of the epiglottis. Histopathology. 1997;30(6):592–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5480804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okami K, Onuki J, Sakai A, Tanaka R, Hagino H, Takahashi M. Sleep apnea due to Kimura’s disease of the larynx. Report of a case. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65(4):242–244. doi: 10.1159/000073125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tasei A, Tsutsumi T, Shimoide Y. A rare case of Kimura’s disease of the epiglottis treated with herbal medicine “Saibokutoh”. Practica Otologica. 2003;96(11):999–1004. doi: 10.5631/jibirin.96.999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akyol U, Tatar EC, Sungur AA. Kimura’s disease in paraglottic space. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(6):989–990. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwai H, Nakae K, Ikeda K, Ogura M, Miyamoto M, Omae M, Kaneko T, Yamashita T. Kimura disease: diagnosis and prognostic factors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;37(2):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badr A, Abdul-Haleem A, Carlsen E. Kimura disease of the epiglottis. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(4):328–32. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0078-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamitani T, Taki M, Matsui M. A case of Kimura’s disease of the parotid gland, eyelid and epiglottis. Jibi Inkoka, Tokeibu Geka. 2008;80(10):737–741. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawata R, Yoshimura K, Ichihara T, Takenaka H, Tsuji M. Kimura’s disease of the epiglottis: resection by a lateral pharyngotomy approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(1):148–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim KH, Ang AHC, Tan HKK. Kimura disease of the epiglottis: an unusual cause of upper airway obstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2012;2(1):18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pedex.2011.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]