Abstract

So far most studies on adult neurogenesis aimed to unravel mechanisms and molecules regulating the integration of newly generated neurons in the mature brain parenchyma. The exceedingly abundant amount of results that followed, rather than being beneficial in the perspective of brain repair, provided a clear evidence that adult neurogenesis constitutes a necessary feature to the correct functioning of the hosting brain regions. In particular, the rodent olfactory system represents a privileged model to study how neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis interact with sensory functions. Until recently, the vomeronasal system (VNS) has been commonly described as being specialized in the detection of innate chemosignals. Accordingly, its circuitry has been considered necessarily stable, if not hard-wired, in order to allow stereotyped behavioral responses. However, both first and second order projections of the rodent VNS continuously change their synaptic connectivity due to ongoing postnatal and adult neurogenesis. How the functional integrity of a neuronal circuit is maintained while newborn neurons are continuously added—or lost—is a fundamental question for both basic and applied neuroscience. The VNS is proposed as an alternative model to answer such question. Hereby the underlying motivations will be reviewed.

Keywords: accessory olfactory bulb, AOB, vomeronasal, VNO, neurogenesis, pheromones, plasticity, innate

Introduction

The idea of a mature brain as an organ with limited growth, cell renewal and rewiring has considerably changed since pioneer studies on adult neurogenesis (Altman and Das, 1966; Altman, 1969; Graziadei and Monti-Graziadei, 1979; Lledo and Gheusi, 2006; Kempermann, 2012). In the adult mammalian brain, neural progenitors are present in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles and the hippocampal subgranular zone (SGZ) where they give rise respectively to Dlx2/5/6-derived GABAergic olfactory bulb interneurons and glutamatergic granule cells of the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus (Doetsch et al., 1999; Seri et al., 2001; Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009). Admittedly, neurogenesis in other adult brain regions is generally believed to be very limited under physiological conditions (Nishiyama et al., 1996; Horner et al., 2000; Dawson et al., 2003; Luzzati et al., 2006, 2011; Bonfanti and Peretto, 2011), although it could be induced after injury (Ramaswamy et al., 2005; Gould, 2007; Yu et al., 2008; Kernie and Parent, 2010; Saha et al., 2013) or as a consequence of tissue inflammation and degeneration (Buffo et al., 2008; Ohira et al., 2010; Luzzati et al., 2011; Belarbi and Rosi, 2013). Nowadays several approaches have been developed to maintain and manipulate pluripotent stem cells in-vitro in the perspective of brain repair (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yamanaka and Blau, 2010). Particularly the rodent olfactory bulb (OB) has been widely studied to clarify the logic of neuronal stem-cell biology in the SVZ opening new venues to brain-repair strategies, cell transplants techniques in disease models and other translational approaches (Gage and Temple, 2013).

However, the development of clinical translations cannot stand aside the basic research, focused in this case on the physiologic function of the neurogenic regions in-vivo (see for critical reviews on this point Lau et al., 2008; Lindvall and Kokaia, 2010).

In addition, studying OB neurogenesis may yield new insights in the biology of olfaction, being olfactory sensory activity and behaviors easy readouts of any experimental manipulation in rodents.

Understanding how the environment affects newborn neurons integration into mature networks, and consequently normal brain function, are certainly meaningful aims to define the boundaries between physiology and pathology in translational neuroscience. The restoration of brain connectivity after trauma or the comprehension of the etiology of major brain disorders may certainly move forward and undoubtedly more clinically oriented approaches would benefit from the unbiased attempts of basic research to address these issues (Fang and Casadevall, 2010; Enserink, 2013). In the present manuscript a special attention will be given to neurogenesis in a particular olfactory subsystem—namely the accessory/vomeronasal system (VNS)—due to the fact that, despite its behavioral relevance in rodent sociality, it received so far a minor deal of attention. The main point hereby stressed concerns the unclear relationship between form—plastic and changing—and function—presumably stable, innate—in the VNS. Due to its distinct peculiarities, compared to the rest of the olfactory system, the VNS offers an unparalleled opportunity to analyze how newborn neurons constantly integrate into mature circuits without interfering with the physiological behavioral and endocrine development. Recent findings on neurogenesis in the vomeronasal organ (VNO) and accessory olfactory bulb (AOB) will be listed and discussed with a particular emphasis on the AOB, since it represents the first central brain region of this olfactory pathway.

The vomeronasal system as a model to study adult neurogenesis

Neurogenesis in the OB has been studied predominantly in the main olfactory pathway. The neurons constantly replaced in the main olfactory bulb (MOB) are GABAergic local interneurons (periglomerular, PGs, and granule cells, GCs) mainly derived from the Dlx2 subpallial domain in the SVZ (Puelles et al., 2000; Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo, 2002; Lledo and Gheusi, 2006; Whitman and Greer, 2009). These cells play a key role in regulating MOB input and output activity (Spors et al., 2012), and they have been proved to actively contribute to olfactory processing (Mandairon et al., 2011; Alonso et al., 2012) given their activity dependent survival and functional recruitment (Magavi et al., 2005; Mouret et al., 2008; Sultan et al., 2011a,b). In most of these reports the role of newborn neurons in the context of olfactory discrimination, short and long-term olfactory memory has been analyzed using synthetic odor compounds or artificial behavioral tasks. These paradigms are well suited to answer specific questions about the logic of sensory transduction (e.g., tuning, discrimination, detection threshold). However, framing the same analysis within the contexts of reproduction and sociality may be more informative to clarify whether neurogenesis itself is necessary or not to the mature brain. Indeed reproduction and sexual selection constitute a powerful evolutionary force and therefore the primary drive for any functional adaptation of a brain circuit. So far only few recent studies correlated MOB neurogenesis, with the regulation of social behavior in mice (see for example Larsen et al., 2008; Kageyama et al., 2012; Monteiro et al., 2013). The functional studies on the role of neurogenesis in the VNS are considerably fewer despite the major contribution of the VNS in rodent sociality (Tirindelli et al., 2009; Mucignat-Caretta, 2010; Chamero et al., 2012; Ibarra-Soria et al., 2013). Moreover the presence of neurogenesis in the AOB has been largely ignored, if not denied (Mak et al., 2007). However, neurogenesis occurs postnatally both at the VNS periphery, in the VNO, and more centrally, in the AOB (VNO: Barber and Raisman, 1978; Graziadei and Monti-Graziadei, 1979; Jia and Halpern, 1998; Giacobini et al., 2000; Martinez-Marcos et al., 2005; Weiler, 2005; Brann and Firestein, 2010; Enomoto et al., 2011; AOB: Bonfanti et al., 1997; Martínez-Marcos et al., 2001; Peretto et al., 2001; Huang and Bittman, 2002; Oboti et al., 2009, 2011; Figure 1). Interestingly cell survival in the AOB is higher after sensory stimulation around weaning and puberty onset (ca. 4 weeks in mice) when, after gonadal and endocrine maturation, social and reproductive behaviors become more clearly manifest (Oboti et al., 2011). Concurrently, despite the VNO seems to be already functional at birth (Coppola and O'Connell, 1989), the process of wiring and synaptogenesis of the VNO-AOB circuit has been shown to extend postnatally and to reach maturity only around the third postnatal week (Horowitz et al., 1999).

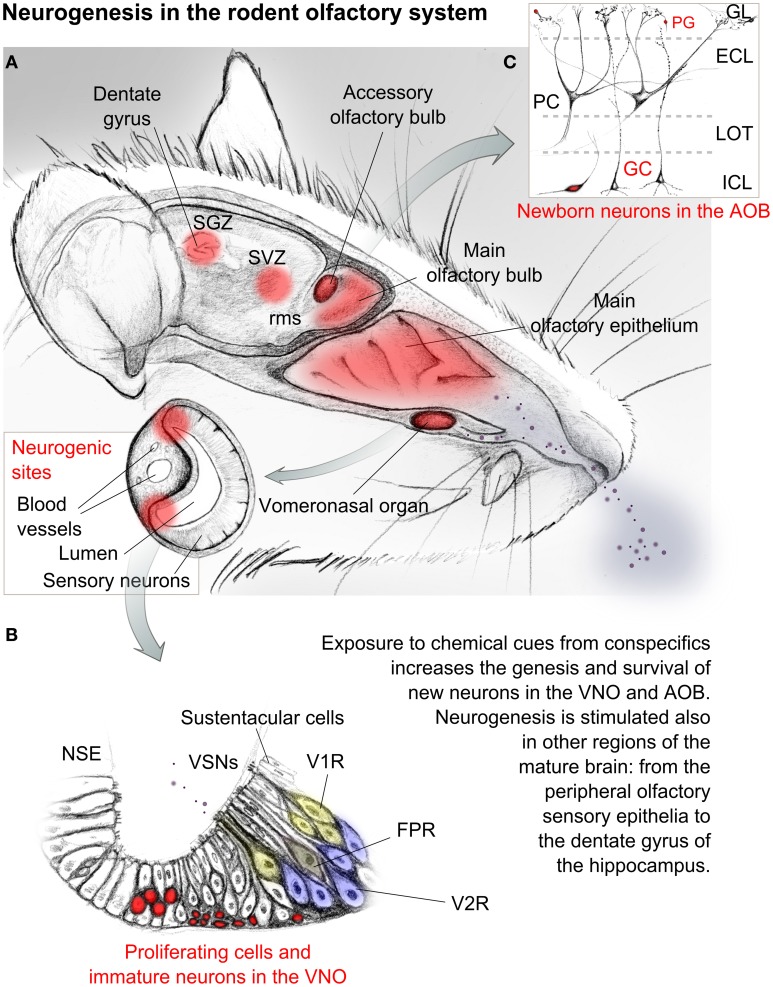

Figure 1.

Sketched representation of the mouse olfactory system. Central and peripheral neurogenic regions are evidenced in red. (A) Social odors and chemical cues are detected through the main olfactory epithelium and the vomeronasal organ, which is enclosed in a bony capsule opened rostrally toward the nasal cavity. A highly vascularized cavernous tissue flanking the organ allows tissue contraction and therefore the access of mucuous fluids transporting chemical cues toward the sensory epithelium. (B) Enlarged view of the vomeronasal sensory epithelium and its cell types. Proliferating cells are localized at the lateral and basal margins of the matured sensory epithelium. Sensory neurons here located send axonal projections to the accessory olfactory bulb. (C) Simplified anatomy of the accessory olfactory bulb cellular layers. Cells evidenced in red in (B,C) represent immature or regenerating neurons. Abbreviations: SGZ, subgranular zone; SVZ, subventricular zone; rms, rostral migratory stream; GL, glomerular layer; PG, periglomerular cell; ECL, external cellular layer; ICL, internal cellular layer; LOT, lateral olfactory tract; PC, principal cell; GC, granule cell; V1R, vomeronasal receptor neuron type1; V2R, vomeronasal receptor neuron type2; FPR, formyl peptide receptor neuron; VSNs, vomeronasal sensory neurons; NSE, non-sensory epithelium.

This seems to suggest the occurrence of a post-pubertal functional tuning of the VNS circuitry through neurogenesis, plasticity and constant rewiring, which goes beyond an early postnatal maturation of the system, similarly to the main olfactory system (Figure 1; Bonfanti and Peretto, 2011; Lepousez et al., 2013).

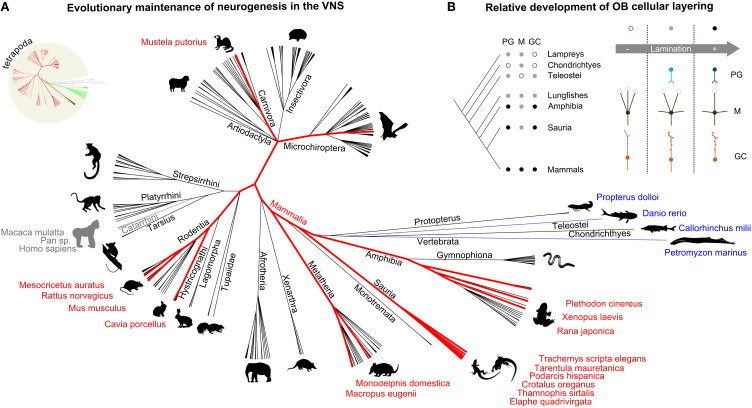

The reason why the VNS has been neglected by more recent studies on olfactory neurogenesis is possibly due to two main reasons. Firstly, the VNS is absent in humans, therefore limiting the interest in extending the study of olfactory neurogenesis to this system in rodents. Secondly, this sensory system has been traditionally associated to pheromone detection, innate signal processing and stereotyped endocrine responses, for which plasticity, neurogenesis, and rewiring are apparently not necessary. Nonetheless, regardless of any homologies in the mammalian olfactory systems, we undoubtedly share with rodents and other species the functions that this sensory pathway specifically regulates, when present (Figure 2). Therefore, one of the main reasons why neurogenesis in the rodent VNS deserves more attention is related to understanding the neural bases of mammalian neuroendocrine and behavioral development and how they are affected by environmental cues. Ultimately, the rodent VNS is a suitable and simple model to tackle wider issues related to other mammals in general, humans included.

Figure 2.

Neuronal plasticity in the vomeronasal system is a conserved trait across several vertebrate species. The increased organizational complexity of the olfactory systems is plausibly related to their protracted development through postnatal neurogenesis. (A) Cladogram representing the main vertebrate taxa in which the presence of a vomeronasal system has been reported (black lines). Taxa indicated in blue possess the cellular and molecular elements of the VNS, without a defined structural organization. Old world monkeys are indicated in gray, as reference, although they generally do not possess a functional VNS. The species (and related taxa) in which neurogenesis in the VNS has been reported are highlighted in red. (B) Features of the vertebrate olfactory systems include: more defined cellular layering (white: low, gray: moderate, black: high lamination), presence of periglomerular cells, PG (white: absent, gray: ambiguous, black: present), development of mitral cell secondary dendrites, M (white: absent, only multiglomerular primary dendrites, gray: presence of both multiglomerular primary dendrites and secondary dendrites, black: monoglomerular primary dendrites and secondary dendrites), loss of granule cell axon, GC (white: smooth dendrites, axon, gray: spiny dendrites, axon, black: spiny dendrites, no axon). Sources: (Meisami and Bhatnagar, 1998; Eisthen, 2000; Halpern and Martinez-Marcos, 2003; Grus and Zhang, 2008; Eisthen and Polese, 2009; Mucignat-Caretta, 2010); NCBI.

The aim of the following paragraphs is to evaluate different aspects of VNS neurogenesis ranging from the phenotypes of newly generated neurons to their functional impact on specific circuits. The comparative description accompanying each of these points aims to open new questions for a wide range of approaches. These entailing the developmental, circuit, and system biology of olfaction. Aside, emerges the interesting—yet unanswered—question of how this olfactory subsystem acquires its function in the precise way it does, while its circuits are constantly changing. Rather than supporting the hardwired nature of this process, the evidences here reported suggest a necessary role for neurogenesis, neuronal plasticity, and environmental adaptation for its accomplishment.

Neurogenesis in the vomeronasal organ

Olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) are directly exposed to the environment to detect chemical stimuli through membrane bound receptors on their cilia (MOS) or microvilli (VNS). In the olfactory epithelia, ciliated and microvillus neurons, supporting cells and ensheating glial cells are constantly renewed during pre- and postnatal development (Murdoch and Roskams, 2008) by neural stem cells deriving from both neural crest and olfactory placode precursor lineages (Katoh et al., 2011; Heron et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2013). Due to this peripheral localization, OSN renewal has been generally associated to tissue growth (during development), homeostasis and repair (during adulthood) as gene expression patterns are maintained very similar (Heron et al., 2013). In the VNO, as in the MOE, the proliferation of different subsets of neuronal progenitors gives rise to OMP-positive mature receptor neurons (Murdoch and Roskams, 2008; Enomoto et al., 2011) but begins slightly later. In the rat olfactory epithelium OMP starts to be expressed at E14, while in the VN epithelium it occurs only at P2 (Kulkarni-Narla et al., 1997). In the mouse OMP is expressed in vomeronasal sensory neurons (VSNs) a few days earlier, during the last week of gestation (Tarozzo et al., 1998). These data indicate that VSNs are not fully developed at birth as most of their maturation begins and occurs postnatally.

Mature VSNs can be divided in three main families, depending on the receptors expressed and the ligands they have been reported to detect: V1Rs, activated preferentially by low molecular weight (LMW) hormone metabolites and other small molecules possibly contained in urine and bodily secretions; V2Rs, activated mainly by high molecular weight (HMW) peptidic compounds such as lipocalins, or smaller MHC peptides; formyl peptide receptors (FPRs), involved in the immune cell response to infections (Chamero et al., 2012; Figure 1B). V1R expressing neurons populate the apical portion of the sensory epithelium, V2Rs are located more basally while FPRs are more heterogeneously distributed (Rivière et al., 2009).

The earlier steps of VSNs differentiation are regulated by the proneural bHLH genes Mash1 and Neurogenin1, the former maintaining stem-cell progenitors, the second determining their multipotency (Cau et al., 2002), which is further regulated by the gene Ctip2 (Enomoto et al., 2011). Accordingly, loss of Ctip2 shifts the V1R/V2R differentiation ratio toward the V1R phenotype, suggesting a pivotal role in VSNs maturation and the possibility that the V2R-lineage entails both V1R and V2R committed neurons (Enomoto et al., 2011). The molecular mechanisms specifying the FPR lineage are not known.

VSNs proliferation is not homogeneous across the sensory epithelium but seems to be increasingly more localized at its margins, as development proceeds (Barber and Raisman, 1978; Giacobini et al., 2000; Martinez-Marcos et al., 2005; de la Rosa-Prieto et al., 2011). Although immature VSNs show limited migratory capabilities during adulthood (Martinez-Marcos et al., 2005; de la Rosa-Prieto et al., 2011), their proliferation increases until 2 months of age, in mice (Weiler, 2005; Brann and Firestein, 2010). Newborn VSNs are produced in clusters giving rise to patterned waves of migrating neurons (as observable by DCX immunohistochemistry). It would be interesting to clarify whether neurons expressing receptors of the same family are simultaneously generated at a given time. However, BrdU experiments suggested that both V1Rs and V2Rs are produced at the same pace in physiological conditions (de la Rosa-Prieto et al., 2010). Interestingly, postnatal development and growth seems to be present also in the non-sensory epithelium (NSE, Figure 1B) of the VNO (Garrosa et al., 1998; Elgayar et al., 2013).

Despite the vast number of MOE receptor genes (ca 1500 in the mouse) each OSN expresses only one of them. In the VNO this rule is not followed since each VSN may express more than one receptor gene (Martini et al., 2001; Silvotti et al., 2007; Ishii and Mombaerts, 2011). Interestingly, the phenotypic identity of newborn VSNs can be affected by histone modifications following application of urine ligands in-vitro (Xia et al., 2010). While application of HDAC inhibitors to cultured VSNs decreases the expression of immature neuronal marker Nestin, and increases the expression of markers of differentiation such as Map2, Neuro D1-D2, and V2R genes (Xia et al., 2010). It remains to be clarified whether these effects, represent a generalized adaptive response of the VNO epithelium to sensory stimulation or if it constitutes a mechanism to selectively specific subsets of newborn VSNs, as shown in the MOE (Watt et al., 2004; Dias and Ressler, 2013). Both simple parsimony and recent evidences suggest that this latter might be the case (Broad and Keverne, 2012). However, other factors such as odor exposure (Xia et al., 2006), hormonal changes (Kaba et al., 1988; Paternostro and Meisami, 1996) and sensory activity (Hovis et al., 2012) contribute to postnatal VNO neurogenesis and VNO-AOB rewiring indicating the persistence of constant adjustments in this circuit. Altogether these results strongly suggest that VNO neurogenesis do not serves mere tissue homeostasis and repair, but actively contributes to the functional tuning of the organ during postnatal development. A possibility still largely unexplored.

Neurogenesis in the accessory olfactory bulb, a comparative note

Afferent axons from VSNs reach the brain at the level of the dorsal part of the OB. Here they form glomerular-like structures with the apical dendrites of a separate group of projection neurons which constitute the accessory olfactory bulb (AOB; Figures 1A,C). As for the MOB, their activity is regulated by inhibitory glomerular and granule cells (Figure 1C). Neurogenesis in the AOB involves mainly these two cell types (Oboti et al., 2009). Despite earlier doubts on its presence, several lines of evidence support the idea that adult neurogenesis represents a constitutive feature of the AOB. It can be found in adult mice of both genders (Oboti et al., 2009; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011), in adult rats (Peretto et al., 2001) and rabbits (personal observation). In addition, AOB neurogenesis has been reported not only in mammals (Altman and Das, 1966; Altman, 1969; Hinds, 1968a,b; Kaplan and Hinds, 1977; Bayer, 1983; Kaplan, 1985; Kishi, 1987), but also in other vertebrate species such as amphibians (Fritz et al., 1996), and reptiles (Garcia-Verdugo et al., 1989; Pérez-Cañellas and García-Verdugo, 1996; Pérez-Cañellas et al., 1997) indicating that it represents a conserved trait across different taxa (Figure 2A), rather than a parallel convergence. Neuronal plasticity in the olfactory system occurs independently of the presence of a discernible VNS, as in primates, fishes, cetaceans, and birds for example (García-Verdugo et al., 2002; Mucignat-Caretta, 2010); Figure 2A). In addition, taxa in which some of the typical cellular and molecular elements of the VNS are present, although with different levels of organization (as anurans, lungfishes, sea lampreys, teleosts, and cartilaginous fishes; Eisthen and Wyatt, 2006; Figure 2A), retain neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis in the primary olfactory structures during post-hatching and more mature stages. This indicates that a plastic VNS may not be an apomorphic (underived) trait of terrestrial vertebrates (Figure 2A; Table 1). In bat species, even though the VNS is not always developed, the presence of immature neurons typically expressing doublecortin (DCX) has been noted in the AOB (Amrein I., personal communication).

Table 1.

List of representative studies explicitly focused on VNO and AOB neurogenesis.

| Species | VNO | AOB |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | Barber and Raisman, 1978 | Hinds, 1968a,b |

| Monti-Graziadei, 1992 | Bonfanti et al., 1997 | |

| Cappello et al., 1999 | Oboti et al., 2009–2011 | |

| Giacobini et al., 2000 | Veyrac and Bakker, 2011 | |

| Weiler, 2005 | Sakamoto et al., 2011 | |

| Martinez-Marcos et al., 2005 | Nunez-Parra et al., 2011 | |

| Murdoch and Roskams, 2008 | ||

| Brann and Firestein, 2010 | ||

| Enomoto et al., 2011 | ||

| Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | Monti-Graziadei, 1992 | Altman and Das, 1966 |

| Weiler et al., 1999a–2005 | Altman, 1969 | |

| Inamura et al., 2000 | Kaplan and Hinds, 1977 | |

| Martínez-Marcos et al., 2000 | Kishi, 1987 | |

| Matsuoka et al., 2002 | Bayer, 1983 | |

| Peretto et al., 2001 | ||

| Corona et al., 2011 | ||

| Portillo et al., 2012 | ||

| Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | Othman, 2011 | Personal observation |

| Guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) | Personal observation | |

| Hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) | Ichikawa et al., 1998 | Huang and Bittman, 2002 |

| Taniguchi and Taniguchi, 2008 | ||

| Opossum (Monodelphis domestica) | Jia and Halpern, 1998 | Shapiro et al., 1997 |

| Shapiro et al., 1997 | Martínez-Marcos et al., 2001 | |

| Wallaby (Macropus eugenii) | Ashwell et al., 2008 | Ashwell et al., 2008 |

| Ferret (Mustela putorius furo) | Weiler et al., 1999b | |

| Bat (various spp.) | Amrein et al., 2007 (OB) | |

| Garter snake (Tamnophis sirtalis) | Wang and Halpern, 1982 | |

| Striped snake (Elaphe quadrivirgata) | Kondoh et al., 2012 | |

| Wall lizard (Podarcis hispanica) | Garcia-Verdugo et al., 1989 | |

| Sampedro et al., 2008 | ||

| Font et al., 2012 | ||

| Red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) | Pérez-Cañellas et al., 1997 | |

| Gecko (Tarentola mauritanica) | Pérez-Cañellas and García-Verdugo, 1996 | |

| Clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) | ||

| No | Hansen et al., 1998 | Fritz et al., 1996 |

| Higgs and Burd, 2001 | ||

| Yes | Endo et al., 2011 | |

| Salamander (Plethodon cinereus) | Dawley et al., 2000 | |

| Dawley and Crowder, 1995 | ||

| Japanese brown frog (Rana japonica) | Taniguchi et al., 1996 | |

| Zebra fish (Danio rerio) | Byrd and Brunjes, 2001(OB) | |

| Adolf et al., 2006 (OB) |

Species in which neurogenesis in the VNS components of the olfactory system could be present are indicated italics.

In mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs SVZ neuronal progenitors give rise to neuroblasts integrating in the AOB mainly as granule cells localized in the inner granule cell layer, below the lateral olfactory tract. The presence of newborn neurons in periglomerular layer is very limited, possibly reflecting a much slower turn-over rate of PGs (Martínez-Marcos et al., 2001; Peretto et al., 2001; Oboti et al., 2009; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). A limited number of cells can be found in the plexiform layer between the GC and PG layers, where principal cells (PC) are located (Oboti et al., 2009; PCs are homologous to MOB mitral cells), possibly representing other cell types such as external granule cells and dwarf cells (Larriva-Sahd, 2008). The increasing importance of local interneurons for OB signal elaboration, reflected by the increased complexity in OB structural lamination (Eisthen and Polese, 2009; Figure 2B), implies a possible correlation with the maintenance of their turnover. Overall, OB neurogenesis may represent a necessary and conserved feature of the olfactory pathways, reminiscent of the higher neuronal plasticity showed by the paleocortex, to which it belongs (see Table 1 for a list of representative studies explicitly focused on VNO or AOB postnatal development and neurogenesis). In the following paragraphs, attention will be given to the anatomy of the AOB, the phenotypes of AOB newborn cells and the possible role in its circuitry considering the present knowledge about its role in the VNS.

Neurogenesis in the two accessory olfactory bulb subregions

Both the glomerular and principal cell (PC) layer of the AOB look clearly partitioned by the segregated V1R/Gai2 and V2R/Gao afferent fibers. Axonal projections from these two neuronal populations establish synaptic contact with either the anterior (aAOB) or posterior (pAOB) AOB, respectively. This separation is visible in the PC layer neuropil (linea alba, Larriva-Sahd, 2008). In rodents the V1R and V2R pathways have been shown to selectively respond to low molecular weight organic molecules (Leinders-Zufall et al., 2000; Sugai et al., 2006) and high molecular weight compounds of peptidic nature, respectively (Leinders-Zufall et al., 2004, 2009; Kimoto et al., 2005). Accordingly to this functional dichotomy, differences in c-Fos expression patterns in the two AOB regions have been observed after exposure to gender related odors in male and female mice (Kumar et al., 1999; Halem et al., 2001). Interestingly, in mice and rats (Peretto et al., 2001; Oboti et al., 2009, but not in opossums Martínez-Marcos et al., 2001), newborn cells reaching the AOB in physiological conditions (no odor exposures) seem to be unequally distributed along the rostro-caudal axis. This may reflect a differential rate of development of the two AOB sub-regions or alternatively be related to the V1R/V2R functions being subjected to differential adaptive pressures in a given eco-ethological niche (Suárez et al., 2011a,b). Accordingly, recently a dual embryonic origin of the AOB has been proposed (Huilgol et al., 2013). In this study, Huilgol and coauthors showed that PCs in the pAOB derive from the thalamic eminences at the diencephalic/telencephalic boundary (DTB) from Lhx5 expressing neurons, as part of the amygdala, BST and Cajal-Retzius neurons (Huilgol et al., 2013), while the aAOB PCs share common origin with MOB mitral cells, as indicated by Tbx21 expression in the OB primordium (Huilgol et al., 2013). The DTB is evolutionary conserved in amphibians and mammals indicating that the pAOB may be a residue of the earliest sensory systems originating from the thalamic eminences and controlling olfactory responses in amphibians (Krug et al., 1993; Huilgol et al., 2013). However, the apparent morphology of AOB granule cell layer does not reveal a similar dichotomy, as AOB granule cells connectivity may be more ambiguous (Larriva-Sahd, 2008). Despite the different origin of pAOB projection neurons, immature GABAergic interneurons of both the aAOB and pAOB may include cells derived from the same Dlx2/5/6, Emx1, and Meis2 lineages in the SVZ (Kohwi et al., 2007; Agoston et al., 2013). Overall this suggests the existence of different regulatory mechanisms locally specifying the phenotype of cells belonging to the same neuronal lineage but integrating in different circuits (aAOB vs. pAOB, but also AOB vs. MOB). Further understanding of the underlying mechanisms would extend our knowledge of the morphological and functional adaptations newborn neurons may be capable of. In addition, given the functional segregation of the VNS circuits (V1R-aAOB, V2R-pAOB), different levels of neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis may reflect a different degree of adaptability to the diversity of chemical stimuli each subsystem elaborates. However, despite the differences these features may have a similar functional relevance for their proper function.

Phenotypes of newborn neurons in the accessory olfactory bulb

New neurons migrating from the SVZ through the rostral migratory stream, reach all AOB layers: glomerular (Gl), external (ECL), and internal (ICL) cellular layers (Larriva-Sahd, 2008). At present no detailed analysis has been made to identify these cell types. Moreover, the presence in the MOB of newly generated tbr2-derived glutamatergic cells (Brill et al., 2009) and GABAergic-serotonergic (Inta et al., 2008) interneurons has been recently proven, while in the AOB it remains to be verified.

In the MOB, the cell types forming the glomerulus (juxtaglomerular cells) are classified in periglomerular (PG), short axon (SA) and external tufted (ET) cells, based on their neurochemistry, morphology, and connectivity. Juxtaglomerular cells can be divided in two main GABAergic chemotypes based on the expression of different isoforms of the GABA synthesis enzyme—GAD-65, GAD-67—together with other markers such as dopamine (DA), or its synthesis enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), calbindin, calretinin, and others (Shipley et al., 2004). Virtually all dopaminergic neurons express GAD-67, while little if no overlap is present between the GAD-65 and the TH sub-populations (Kiyokage et al., 2010). As typical SA cells, TH-GAD-67 neurons innervate multiple glomeruli while GAD-65 neurons are mostly monoglomerular with only few secondary processes directed to other glomerular formations (Aungst et al., 2003; Kiyokage et al., 2010).

In the AOB glomerular layer scarce if not absent GAD-67 staining has been reported together with almost complete lack of TH expression (Mugnaini et al., 1984; Oboti et al., 2009). This possibly indicates a predominance in the AOB of the monoglomerular GAD-65 chemotype. However, newly generated cells with morphological features of both PG uniglomerular cells and SA multiglomerular cells have been identified in the AOB (Oboti et al., 2009) suggesting that the low levels of GAD-67 expression do not necessarily imply the absence of SA-like cells (Mugnaini et al., 1984; Larriva-Sahd, 2008).

In the MOB, dopaminergic PG cells are responsible of thresholding mitral cell firing in response to olfactory inputs (Pírez and Wachowiak, 2008). The lack of dopaminergic signaling in the AOB may imply a minor need for gain control of vomeronasal inputs on PCs being their firing threshold possibly determined by input coincidence from heterotypical glomerular afferents (Meeks et al., 2010).

Other inhibitory cells located more deeply in the AOB are external and internal granule cells, located above and below the lateral olfactory tract (LOT), respectively. Evidence showed the vast majority of newborn cells reaching the AOB is represented by internal granule cells (Oboti et al., 2009; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). In the ICL main accessory cells are also present (MACs, Larriva-Sahd, 2008) and are distinguishable from granule cells by larger soma and nuclear size and by their sporadic presence in the LOT. Although newborn cells can be often found in the LOT, their nuclear size was always comparable to normal granule cells (external granule cells, in this case), thus limiting the likelihood for MACs to be regenerated during adulthood.

Recently, in the rat MOB the presence of newborn neurons in the external plexiform layer (EPL) has been proved (Yang, 2008). These neurons have been reported to be PV/CR expressing Van Gehuchten cells, multipolar cells and superficial SA cells (Yang, 2008). Since DCX- and BrdU-positive cells can be found in homologous locations in the AOB (ECL), the presence here of these cell types is possible but yet to be investigated.

It is not known whether SVZ-derived interneurons migrating to the AOB belong to the same lineage of those in the MOB. It is possible that genetically distinct populations of interneurons are heterogeneously distributed in the two OB sub-regions. Recently, viral fate-mapping experiments revealed the mosaic nature of the SVZ proliferative domains giving rise to different and heterogeneous pools of GABAergic interneurons (Merkle et al., 2007). However, upon inspection of the material used in this study, no apparent regionalization of either aAOB- or pAOB-committed progenitors was found (viral infected GFP+ cells were found in the AOB of mice injected at all SVZ levels, personal observation). Interestingly, although most of newborn AOB neurons labeled with BrdU coexpress NeuN at 4 weeks of age (80%) as in the MOB, the level of coexpression with other interneuronal markers is much lower (BrdU/GABA, BrDU/GAD-67, and BrdU/calretinin reach only about the 30%; Oboti et al., 2009) (MOB: BrdU/GAD67 is about 80% in the GrL and 30% in the GL; Parrish-Aungst et al., 2007). These results indicate that the phenotype of AOB newborn neurons is similar to the MOB but conserve some peculiarities specified either locally or in the SVZ. The different relative abundance of morpho- and chemo-types in this structure, renders the AOB an interesting circuit to study the differential role of a given cell type in different compartments of the bulbar circuitry. For example by studying PC (AOB mitral cell homolog) electrical responses to peripheral nerve stimulations it would be possible to clarify to which extent SA cells in the AOB may be dispensable—in case of their limited presence in this structure—for a certain olfactory coding task, or—by comparison—which specific function do they serve when present in other bulbar circuits.

Sensory activity-dependent survival and function of newborn cells

As shown by olfactory enrichment or deprivation studies, the maturation and survival of newborn neurons in the MOB depends on sensory inputs (Cummings et al., 1997; Rochefort et al., 2002; Mandairon et al., 2006). Newborn neurons reach the MOB in massive waves but are gradually selected during integration into local circuits (Petreanu and Alvarez-Buylla, 2002) activated by sensory inputs (Magavi et al., 2005; Mouret et al., 2008; Sultan et al., 2011a,b). Importantly, loss or ablation of newborn neurons in the MOB can impair olfactory function (Breton-Provencher et al., 2009; Mandairon et al., 2011) since younger cells are preferentially involved in these circuits (Nissant et al., 2009; Alonso et al., 2012).

Although renewing at a slower rate (Oboti et al., 2009), newborn cells in the AOB are likely to similarly contribute to VNS function. As in the MOB, sensory activity increases the survival of newborn neurons in the AOB (Oboti et al., 2009, 2011; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). This effect is mediated by chemical cues present in urine or bodily secretions (Nunez-Parra et al., 2011; Oboti et al., 2011), it is abolished after VNO genetic functional ablation in trpc2-ko mice (Oboti et al., 2011), it is persisting until 7 months of age (Nunez-Parra et al., 2011), and gives rise to neurons responding preferentially to experienced odor stimuli (Oboti et al., 2011).

The presence of gender related differences in AOB neurogenesis is controversial (no differences in CD1 mice Oboti et al., 2009, 2011; differences in B6 mice, Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). However, the effect of odor experience on AOB neurogenesis seems to be particularly evident in post-pubertal female mice after male odor stimulation (Oboti et al., 2009, 2011; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). This seems particularly evident in the aAOB upon chronic exposure to low molecular weight (LMW) chemical cues present in male urine, which are mainly detected by the V1R neurons (Oboti et al., 2011). Larger protein compounds sensed through V2Rs are instead ineffective on neuronal survival in neither of the two AOB regions (Oboti et al., 2011). However, a lack of increase in surviving cells after sensory enrichment does not necessarily imply the absence of a sensory dependent functional recruitment of newborn elements, but only that the net amount of surviving cells remains stable. Considering that social odors are important primers on mice development and reproductive behavior, these findings suggest a possible role of AOB postnatal/adult neurogenesis in sensory processing in both genders. Accordingly, eliminating newborn cells in the whole bulb, AOB included, Sakamoto and colleagues showed for the first time an impairment in olfactory functions involving the VNS such as predator-odor avoidance, aggression and mounting in males (Sakamoto et al., 2011). A finding that has been extended to VNO-dependent mate recognition in females (Oboti et al., 2011). The effect of sensory inputs on AOB neurogenesis overall indicates that newborn neurons play an active and possibly relevant role on the vomeronasal circuitry during postnatal and adult life.

Impact of newborn neurons on AOB circuits

A few comparative considerations with the MOB elementary functional unit—the olfactory column—can be insightful in defining the impact of newborn neurons on AOB network activity. The MOB olfactory column is considered equivalent to the cortical columns and barrels in the visual and somatosensory cortices (Shepherd, 2010). It comprises all OSNs projecting to a single glomerulus, all the mitral and tufted cells extending their dendrites to it and all the granule cells connected to these projection neurons. Granule cells can regulate mitral/tufted cell output providing self inhibition through dendrodendritic synapses on mitral cell lateral dendrites within the same column. In addition, they may exert lateral inhibition on adjacent columns by shunting the propagation of action potentials on distal lateral dendrites of extra-columnar mitral cells (Xiong and Chen, 2002). This implies a dual role of granule cells on mitral/tufted cell firing: through self-inhibition within the same column, granule cells may act synchronizing the firing rate of projection neurons belonging to different units while responding to the same sensory input (Dhawale et al., 2010); through lateral inhibition on extracolumnar mitral cells, granule cells may provide contrast enhancement between two different functional units (as other amacrine—axonless—cells in the retina for instance; Migliore and Shepherd, 2008). Both effects have been hypothesized to be relevant for olfactory discrimination (Migliore and Shepherd, 2008; Dhawale et al., 2010; see Lepousez et al., 2013 for a detailed review on this hypothesis). Given the apparent lack of columnar organization in the piriform cortex, this topological motif in the bulbar circuitry probably reflects its cortical like function and represents the modular unit encoding the diversity of olfactory inputs (Haberly, 2001; Migliore et al., 2007). Importantly, the constant re-adjustment of the synaptic inputs caused by renewal of both local interneurons and olfactory fibers has been associated with an optimization of this function (Alonso et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2008; Adam and Mizrahi, 2011).

The AOB appears structurally similar to the MOB, although it retains some peculiar features in both hodology and cell types. However, the occurrence of similar plastic events in both structures motivates the same reasoning done for the MOB. Olfactory glomeruli in the AOB are on average smaller than those in the MOB and appear to be clustered in pseudostratified formations. Contrarily to MOB glomeruli, they receive multiple inputs from different types of VSNs (Takami and Graziadei, 1991; Belluscio et al., 1999; Del Punta et al., 2002), with V1Rs projecting only to the aAOB and V2Rs to the pAOB. In addition, neurons expressing the same receptor/s in the VNO, may project to up to 20–30 different glomeruli (Belluscio et al., 1999), while same-receptor OSNs in the MOE project mainly to two symmetrical glomeruli in the MOB. This conserved pattern seems to underlie a higher degree of input convergence on MOB projection neurons and therefore functional specialization of each olfactory column in the MOB (Hildebrand and Shepherd, 1997; Su et al., 2009; Touhara and Vosshall, 2009) as mitral cells project to a single glomerulus, therefore receiving afferents from OSNs expressing the same receptor. Conversely, AOB PCs reach multiple glomeruli receiving inputs from different VSNs (a feature shared with the OB of fishes: Ngai et al., 1993; Speca et al., 1999). However, AOB projection neurons maintain V1R/V2R segregated apical dendritic arborizations depending on their location in the aAOB and pAOB (Jia and Halpern, 1997). Nonetheless, a cross talk may exist between aAOB and pAOB principal cells via thinner lateral dendrites crossing the midline (Larriva-Sahd, 2008). As a result of their heterotypic connectivity, AOB PCs integrate inputs from different receptor types in the VNO and therefore different ligands. Slice recordings on ex-vivo VNO-AOB intact preparation showed that this is indeed the case (Meeks et al., 2010). Juxtaglomerular complexes in the AOB resemble the functional triads described in the MOB: PG and SA cells have inter- and intra-glomerular projections, external tufted cells contact a single glomerulus.

The limited extent by which AOB PGs are regenerated by SVZ-derived progenitors, together with the above mentioned lack of TH, could be explained by the lack of TH/GAD-67 cells in the AOB. Alternatively, since TH expression levels in PGs are traditionally used as a proxy for olfactory input (Nadi et al., 1981; Baker et al., 1983; Cho et al., 1996) and VNO activity is subordinated to initial odor detection by the MOE (Xu et al., 2005; Slotnick et al., 2010), the lack of TH and GAD-67 in the AOB could be just a consequence of the irregular nature of vomeronasal inputs. The expression patterns of other activity markers (such as cytochrome-c-oxydase or β-secretase-1) in the AOB glomerular layer resemble those in the MOB during sensory deprivation and therefore could support this hypothesis (Yan et al., 2007; He et al., 2014).

Conversely, granule cells in the AOB are the most represented cell type among newly generated neurons (Oboti et al., 2009; Nunez-Parra et al., 2011). They are typically located in the deep ICL (below the LOT) but also in the deeper portion of the ECL and in the LOT, just below PC somata. They project to PC dendrites belonging to the homologous region (aAOB or pAOB), but considering that PC axon collaterals cross repeatedly the two sub-regions, they could receive synaptic inputs from both. In addition their apical dendrites seem to reach the glomerular layer (Larriva-Sahd, 2008), although it is not clear whether they interact synaptically with the juxtaglomerular complex. Interestingly, while EGC dendritic processes appose on PC somata or proximal dendrites, those from IGC seem to localize preferentially on distal and apical processes, between glomeruli and PC somata (Larriva-Sahd, 2008), a feature confirmed by EM studies (Moriya-Ito et al., 2013). This distinction may imply a bias for AOB IGCs toward PC self-inhibition, instead of intercolumnar lateral inhibition. Eventually, since the vast majority of newly generated cells in the adult AOB are IGC, it is appealing to imagine neurogenesis in the AOB as a mechanism to shunt directly input signals from the VNO. Given the variable turnover rate of IGCs during postnatal development, this feature alone would be sufficient to justify changes in the response to vomeronasal sensory cues over time. In addition, given that both the survival and activation of newborn neurons is actively driven by vomeronasal sensory inputs, this selective shunting may contribute to encode stimulus familiarity. In general, a change in IGC turnover rate, together with other physiological changes, may set the timing for certain stimuli to be more or less effective as social signals or endocrine modulators (e.g., effect of male urine odors on female estrous varying depending on kinship or shared fostering). Ultimately, this could represent a possible answer to the question posed by the title of this manuscript.

Overall these observations suggest that newly generated GABAergic interneurons differently contribute to mature AOB circuits, if compared to the MOB. The different nature of GABAergic modulation of AOB output signals is further supported by the firing of AOB PCs, which appears to be longer sustained, if compared to MOB mitral cells (Meeks et al., 2010; Shpak et al., 2012). In addition, given PC heterogeneous glomerular connectivity and the convergence of their centripetal projections to more central targets (Salazar and Brennan, 2001), the information conveyed by their output signals is also different, and probably more complex. As a direct consequence and in the whole system perspective, the impact newborn IGCs have on PC output activity may definitely be higher than that of granule interneurons on MOB mitral cells.

Conclusions

Overall the considerations made in this manuscript are meant to underline that the VNS is not only constitutively plastic but also that this plasticity may constitute the basis for its peculiar function. Eventually the VNS circuitry cannot be considered hardwired but rather able to adjust its connectivity to environmental changes. If the function of the VNS described so far (see for critical views on this point Eisthen and Wyatt, 2006; Mucignat-Caretta et al., 2012) is the result of the interaction between plastic circuits and environmental stimuli, is definitely not known and certainly deserves further investigation. Plausibly neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis are indeed necessary to shape it and maintain it throughout postnatal life. Eventually different rates of neurogenesis can determine the extent by which VNS circuits adapt and tune to a given chemical environment, being it referred to social, reproductive, or aggressive/territorial behaviors. Even though the VNS is not simply the pheromone-detector in the nasal cavity of mammals or other vertebrates (Eisthen and Wyatt, 2006), it would be a challenge of future studies to test the impact of neuronal plasticity and neurogenesis on those functions, commonly associated to pheromone sensing. Indeed studying the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying the neuroendocrine physiology of sociality may yield insights on the etiology of associated anomalies, even in those mammalian species, human included, in which this sensory pathway is not present. For this reason the rodent VNS may represent the unique opportunity to dissect this issue in an animal model in which these features strongly rely on its functional integrity and—plausibly—its capability of cell renewal through adult neurogenesis.

Conflict of interest statement

Figure 1A was adapted from published material, courtesy of Catherine Delphia. Cladogram in Figure 2B was adapted from material copyrighted by Elsevier, courtesy of Heather Eisthen and Elsevier. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Arturo Alvarez-Buylla for sending part of the tissues used for the viral fate-mapping analysis of the SVZ-OB and Carla Mucignat-Caretta, Jan Weiss, Martina Pyrski, and Roberto Tirindelli for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- aAOB

anterior accessory olfactory bulb

- AOB

accessory olfactory bulb

- CR

calretinin

- DCX

doublecortin

- DG

dentate gyrus

- ECL

external cellular layer

- EGC

external granule cell

- ET

external tufted

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GC

granule cell

- Gl

glomerular layer

- HMW

high molecular weight

- ICL

internal cellular layer

- IGC

internal granule cell

- LMW

low molecular weight

- LOT

lateral olfactory tract

- MACs

main accessory cell

- MOB

main olfactory bulb

- MOE

main olfactory epithelium

- MOS

main olfactory system

- NSE

non-sensory epithelium

- OB

olfactory bulb

- OSNs

olfactory sensory neurons

- pAOB

posterior accessory olfactory bulb

- PC

principal cell

- PG

periglomerular cell

- PV

parvalbumin

- SA

short axon cell

- SGZ

subgranular zone

- SVZ

subventricualr zone

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VNO

vomeronasal organ

- VNS

vomeronasal system

- VSNs

vomeronasal sensory neurons.

References

- Adam Y., Mizrahi A. (2011). Long-term imaging reveals dynamic changes in the neuronal composition of the glomerular layer. J. Neurosci. 31, 7967–7973 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0782-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolf B., Chapouton P., Lam C. S., Topp S., Tannhäuser B., Strähle U., et al. (2006). Conserved and acquired features of adult neurogenesis in the zebrafish telencephalon. Dev. biology, 295, 278–293 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agoston Z., Heine P., Brill M. S., Grebbin B. M., Hau A.-C., Kallenborn-Gerhardt W., et al. (2013). Meis2 is a Pax6 co-factor in neurogenesis and dopaminergic periglomerular fate specification in the adult olfactory bulb. Development 141, 28–38 10.1242/dev.097295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M., Lepousez G., Sebastien W., Bardy C., Gabellec M.-M., Torquet N., et al. (2012). Activation of adult-born neurons facilitates learning and memory. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 897–904 10.1038/nn.3108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M., Viollet C., Gabellec M.-M., Meas-Yedid V., Olivo-Marin J.-C., Lledo P.-M. (2006). Olfactory discrimination learning increases the survival of adult-born neurons in the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 26, 10508–10513 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2633-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J. (1969). Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. IV. Cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 137, 433–457 10.1002/cne.901370404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J., Das G. D. (1966). Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. I. A longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 126, 337–389 10.1002/cne.901260302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A., Garcia-Verdugo J. M. (2002). Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. J. Neurosci. 22, 629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrein I., Dechmann D. K. N., Winter Y., Lipp H.-P. (2007). Absent or low rate of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus of bats (Chiroptera). PLoS ONE, 2:e455 10.1371/journal.pone.0000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell K. W. S., Marotte L. R., Cheng G. (2008). Development of the olfactory system in a wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Brain Behav. Evol. 71, 216–230 10.1159/000119711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungst J. L., Heyward P. M., Puche A. C., Karnup S. V., Hayar A., Szabo G., et al. (2003). Centre-surround inhibition among olfactory bulb glomeruli. Nature 426, 623–629 10.1038/nature02185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H., Kawano T., Margolis F. L., Joh T. H. (1983). Transneuronal regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in olfactory bulb of mouse and rat. J. Neurosci. 3, 69–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber P. C., Raisman G. (1978). Cell division in the vomeronasal organ of the adult mouse. Brain Res. 141, 57–66 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90616-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S. A. (1983). 3H-thymidine-radiographic studies of neurogenesis in the rat olfactory bulb. Exp. Brain Res. 50, 329–340 10.1007/BF00239197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belarbi K., Rosi S. (2013). Modulation of adult-born neurons in the inflamed hippocampus. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:145 10.3389/fncel.2013.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluscio L., Koentges G., Axel R., Dulac C. (1999). A map of pheromone receptor activation in the mammalian brain. Cell 97, 209–220 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80731-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L., Peretto P. (2011). Adult neurogenesis in mammals–a theme with many variations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 930–950 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L., Peretto P., Merighi A., Fasolo A. (1997). Newly-generated cells from the rostral migratory stream in the accessory olfactory bulb of the adult rat. Neuroscience 81, 489–502 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00090-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann J. H., Firestein S. (2010). Regeneration of new neurons is preserved in aged vomeronasal epithelia. J. Neurosci. 30, 15686–15694 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4316-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton-Provencher V., Lemasson M., Peralta M. R., Saghatelyan A. (2009). Interneurons produced in adulthood are required for the normal functioning of the olfactory bulb network and for the execution of selected olfactory behaviors. J. Neurosci. 29, 15245–15257 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3606-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill M. S., Ninkovic J., Winpenny E., Hodge R. D., Ozen I., Yang R., et al. (2009). Adult generation of glutamatergic olfactory bulb interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1524–1533 10.1038/nn.2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad K. D., Keverne E. B. (2012). The post-natal chemosensory environment induces epigenetic changes in vomeronasal receptor gene expression and a bias in olfactory preference. Behav. Genet. 42, 461–471 10.1007/s10519-011-9523-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo A., Rite I., Tripathi P., Lepier A., Colak D., Horn A.-P., et al. (2008). Origin and progeny of reactive gliosis: a source of multipotent cells in the injured brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3581–3586 10.1073/pnas.0709002105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd C. A., Brunjes P. C. (2001). Neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb of adult zebrafish. Neuroscience 105, 793–801 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00215-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappello P., Tarozzo G., Benedetto A., Fasolo A. (1999). Proliferation and apoptosis in the mouse vomeronasal organ during ontogeny. Neurosci. Lett. 266, 37–40 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00262-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E., Casarosa S., Guillemot F. (2002). Mash1 and Ngn1 control distinct steps of determination and differentiation in the olfactory sensory neuron lineage. Development 129, 1871–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamero P., Leinders-Zufall T., Zufall F. (2012). From genes to social communication: molecular sensing by the vomeronasal organ. Trends Neurosci. 35, 597–606 10.1016/j.tins.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J. Y., Min N., Franzen L., Baker H. (1996). Rapid down-regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the olfactory bulb of naris-occluded adult rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 369, 264–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola D. M., O'Connell R. J. (1989). Stimulus access to olfactory and vomeronasal receptors in utero. Neurosci. Lett. 106, 241–248 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90170-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona R., Larriva-Sahd J., Paredes R. G. (2011). Paced-mating increases the number of adult new born cells in the internal cellular (granular) layer of the accessory olfactory bulb. PLoS ONE 6:e19380 10.1371/journal.pone.0019380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D. M., Henning H. E., Brunjes P. C. (1997). Olfactory bulb recovery after early sensory deprivation. J. Neurosci. 17, 7433–7440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawley E. M., Crowder J. (1995). Sexual and seasonal differences in the vomeronasal epithelium of the red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus). J. Comp. Neurol. 359, 382–390 10.1002/cne.903590303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawley E. M., Fingerlin A., Hwang D., John S. S., Stankiewicz C. A. (2000). Seasonal cell proliferation in the chemosensory epithelium and brain of red-backed salamanders, Plethodon cinereus. Brain Behav. Evol. 56, 1–13 10.1159/000006673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. R. L., Polito A., Levine J. M., Reynolds R. (2003). NG2-expressing glial progenitor cells: an abundant and widespread population of cycling cells in the adult rat CNS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 24, 476–488 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00210-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa-Prieto C., Saiz-Sanchez D., Ubeda-Bañon I., Argandoña-Palacios L., Garcia-Muñozguren S., Martinez-Marcos A. (2010). Neurogenesis in subclasses of vomeronasal sensory neurons in adult mice. Dev. Neurobiol. 70, 961–970 10.1002/dneu.20838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa-Prieto C., Saiz-Sánchez D., Úbeda-Bañón I., Mohedano-Moriano A., Martínez-Marcos A. (2011). Maturation of newly born vomeronasal neurons in the adult mice. Neuroreport 22, 28–32 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328341fb66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Punta K., Puche A., Adams N. C., Rodriguez I., Mombaerts P. (2002). A divergent pattern of sensory axonal projections is rendered convergent by second-order neurons in the accessory olfactory bulb. Neuron 35, 1057–1066 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00904-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawale A. K., Hagiwara A., Bhalla U. S., Murthy V. N., Albeanu D. F. (2010). Non-redundant odor coding by sister mitral cells revealed by light addressable glomeruli in the mouse. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1404–1412 10.1038/nn.2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias B. G., Ressler K. J. (2013). Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 89–96 10.1038/nn.3594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F., García-Verdugo J. M., Alvarez-Buylla A. (1999). Regeneration of a germinal layer in the adult mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11619–11624 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisthen H. L. (2000). Presence of the vomeronasal system in acquatic salamanders. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1209–1213 10.1098/rstb.2000.0669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisthen H. L., Polese G. (2009). Evolution of the vertebrate olfactory subsystems, in Evolutionary Neuroscience, ed Kaas J. H. (Boston, MA: Academic Press; ), 447–492 [Google Scholar]

- Eisthen H. L., Wyatt T. D. (2006). The vomeronasal system and pheromones. Curr. Biol. 16, R73–R74 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgayar S. A. M., Eltony S. A., Othman M. A. (2013). Morphology of non-sensory epithelium during post-natal development of the rabbit vomeronasal organ. Anat. Histol. Embryol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/ahe.12073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo D., Yamamoto Y., Nakamuta N., Taniguchi K. (2011). Developmental changes in lectin-binding patterns of three nasal sensory epithelia in Xenopus laevis. Anat. Rec. 294, 839–846 10.1002/ar.21377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto T., Ohmoto M., Iwata T., Uno A., Saitou M., Yamaguchi T., et al. (2011). Bcl11b/Ctip2 controls the differentiation of vomeronasal sensory neurons in mice. J. Neurosci. 31, 10159–10173 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1245-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink M. (2013). Europe. French mathematician tapped to head key funding agency. Science 342:545 10.1126/science.342.6158.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F. C., Casadevall A. (2010). Lost in translation–basic science in the era of translational research. Infect. Immun. 78, 563–566 10.1128/IAI.01318-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font E., Barbosa D., Sampedro C., Carazo P. (2012). Social behavior, chemical communication, and adult neurogenesis: studies of scent mark function in Podarcis wall lizards. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 177, 9–17 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz A., Gorlick D. L., Burd G. D. (1996). Neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb of the frog Xenopus laevis shows unique patterns during embryonic development and metamorphosis. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 14, 931–943 10.1016/S0736-5748(96)00054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage F. H., Temple S. (2013). Neural stem cells: generating and regenerating the brain. Neuron 80, 588–601 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Verdugo J. M., Ferrón S., Flames N., Collado L., Desfilis E., Font E. (2002). The proliferative ventricular zone in adult vertebrates: a comparative study using reptiles, birds, and mammals. Brain Res. Bull. 57, 765–775 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00769-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Verdugo J. M., Llahi S., Ferrer I., Lopez-Garcia C. (1989). Postnatal neurogenesis in the olfactory bulbs of a lizard. A tritiated thymidine autoradiographic study. Neurosci. Lett. 98, 247–252 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90408-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrosa M., Gayoso M., Esteban F. (1998). Prenatal development of the mammalian vomeronasal organ. Microsc. Res. Tech. 41, 456–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini P., Benedetto A., Tirindelli R., Fasolo A. (2000). Proliferation and migration of receptor neurons in the vomeronasal organ of the adult mouse. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 123, 33–40 10.1016/S0165-3806(00)00080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E. (2007). How widespread is adult neurogenesis in mammals? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 481–488 10.1038/nrn2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei P. P., Monti-Graziadei G. A. (1979). Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. I. Morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. J. Neurocytol. 8, 1–18 10.1007/BF01206454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grus W. E., Zhang J. (2008). Distinct evolutionary patterns between chemoreceptors of 2 vertebrate olfactory systems and the differential tuning hypothesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1593–1601 10.1093/molbev/msn107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberly L. B. (2001). Parallel-distributed processing in olfactory cortex: new insights from morphological and physiological analysis of neuronal circuitry. Chem. Senses 26, 551–576 10.1093/chemse/26.5.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halem H. A., Baum M. J., Cherry J. A. (2001). Sex difference and steroid modulation of pheromone-induced immediate early genes in the two zones of the mouse accessory olfactory system. J. Neurosci. 21, 2474–2480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern M., Martinez-Marcos A. (2003). Structure and function of the vomeronasal system: an update. Prog. Neurobiol. 70, 245–318 10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00103-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A., Reiss J. O., Gentry C. L., Burd G. D. (1998). Ultrastructure of the olfactory organ in the clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, during larval development and metamorphosis. J. Comp. Neurol. 398, 273–288 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980824)398:2%3C273::AID-CNE8%3E3.0.CO;2-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Zhang X.-M., Wu J., Fu J., Mou L., Lu D.-H., et al. (2014). Olfactory experience modulates immature neuron development in postnatal and adult guinea pig piriform cortex. Neuroscience 259, 101–112 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron P. M., Stromberg A. J., Breheny P., McClintock T. S. (2013). Molecular events in the cell types of the olfactory epithelium during adult neurogenesis. Mol. Brain 6:49 10.1186/1756-6606-6-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs D. M., Burd G. D. (2001). Neuronal turnover in the Xenopus laevis olfactory epithelium during metamorphosis. J. Comp. Neurol. 433, 124–130 10.1002/cne.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand J. G., Shepherd G. M. (1997). Mechanisms of olfactory discrimination: converging evidence for common principles across phyla. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 595–631 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds J. W. (1968a). Autoradiographic study of histogenesis in the mouse olfactory bulb. I. Time of origin of neurons and neuroglia. J. Comp. Neurol. 134, 287–304 10.1002/cne.901340304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds J. W. (1968b). Autoradiographic study of histogenesis in the mouse olfactory bulb. II. Cell proliferation and migration. J. Comp. Neurol. 134, 305–322 10.1002/cne.901340305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner P. J., Power A. E., Kempermann G., Kuhn H. G., Palmer T. D., Winkler J., et al. (2000). Proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells throughout the intact adult rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 20, 2218–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz L. F., Montmayeur J. P., Echelard Y., Buck L. B. (1999). A genetic approach to trace neural circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3194–3199 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovis K. R., Ramnath R., Dahlen J. E., Romanova A. L., LaRocca G., Bier M. E., et al. (2012). Activity regulates functional connectivity from the vomeronasal organ to the accessory olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 32, 7907–7916 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2399-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Bittman E. L. (2002). Olfactory bulb cells generated in adult male golden hamsters are specifically activated by exposure to estrous females. Horm. Behav. 41, 343–350 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huilgol D., Udin S., Shimogori T., Saha B., Roy A., Aizawa S., et al. (2013). Dual origins of the mammalian accessory olfactory bulb revealed by an evolutionarily conserved migratory stream. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 157–165 10.1038/nn.3297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Soria X., Levitin M. O., Logan D. W. (2013). The genomic basis of vomeronasal-mediated behaviour. Mamm. Genome 25, 75–86 10.1007/s00335-013-9463-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M., Osada T., Costanzo R. M. (1998). Replacement of receptor cells in the hamster vomeronasal epithelium after nerve transection. Chem. Senses 23, 171–179 10.1093/chemse/23.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura K., Sakamoto H., Honda N., Kashiwayanagi M. (2000). Cluster of proliferating cells in rat vomeronasal sensory epithelium. Neuroreport 11, 477–479 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inta D., Alfonso J., von Engelhardt J., Kreuzberg M. M., Meyer A. H., van Hooft J. A., et al. (2008). Neurogenesis and widespread forebrain migration of distinct GABAergic neurons from the postnatal subventricular zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 20994–20999 10.1073/pnas.0807059105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Mombaerts P. (2011). Coordinated coexpression of two vomeronasal receptor V2R genes per neuron in the mouse. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 46, 397–408 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C., Halpern M. (1997). Segregated populations of mitral/tufted cells in the accessory olfactory bulb. Neuroreport 8, 1887–1890 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C., Halpern M. (1998). Neurogenesis and migration of receptor neurons in the vomeronasal sensory epithelium in the opossum, Monodelphis domestica. J. Comp. Neurol. 400, 287–297 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981019)400:2%3C287::AID-CNE9%3E3.0.CO;2-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. V., Choi D. C., Davis M., Ressler K. J. (2008). Learning-dependent structural plasticity in the adult olfactory pathway. J. Neurosci. 28, 13106–13111 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4465-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaba H., Rosser A. E., Keverne E. B. (1988). Hormonal enhancement of neurogenesis and its relationship to the duration of olfactory memory. Neuroscience 24, 93–98 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90314-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R., Imayoshi I., Sakamoto M. (2012). The role of neurogenesis in olfaction-dependent behaviors. Behav. Brain Res. 227, 459–463 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M. S. (1985). Formation and turnover of neurons in young and senescent animals: an electronmicroscopic and morphometric analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 457, 173–192 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb20805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M. S., Hinds J. W. (1977). Neurogenesis in the adult rat: electron microscopic analysis of light radioautographs. Science 197, 1092–1094 10.1126/science.887941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh H., Shibata S., Fukuda K., Sato M., Satoh E., Nagoshi N., et al. (2011). The dual origin of the peripheral olfactory system: placode and neural crest. Mol. Brain 4:34 10.1186/1756-6606-4-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G. (2012). New neurons for “survival of the fittest.” Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 727–736 10.1038/nrn3319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernie S. G., Parent J. M. (2010). Forebrain neurogenesis after focal Ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 267–274 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto H., Haga S., Sato K., Touhara K. (2005). Sex-specific peptides from exocrine glands stimulate mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. Nature 437, 898–901 10.1038/nature04033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi K. (1987). Golgi studies on the development of granule cells of the rat olfactory bulb with reference to migration in the subependymal layer. J. Comp. Neurol. 258, 112–124 10.1002/cne.902580109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokage E., Pan Y.-Z., Shao Z., Kobayashi K., Szabo G., Yanagawa Y., et al. (2010). Molecular identity of periglomerular and short axon cells. J. Neurosci. 30, 1185–1196 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3497-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohwi M., Petryniak M. A., Long J. E., Ekker M., Obata K., Yanagawa Y., et al. (2007). A subpopulation of olfactory bulb GABAergic interneurons is derived from Emx1- and Dlx5/6-expressing progenitors. J. Neurosci. 27, 6878–6891 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0254-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh D., Yamamoto Y., Nakamuta N., Taniguchi K. (2012). Seasonal changes in the histochemical properties of the olfactory epithelium and vomeronasal organ in the Japanese striped snake, Elaphe quadrivirgata. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 41, 41–53 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2011.01101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein A., Alvarez-Buylla A. (2009). The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 149–184 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug L., Wicht H., Northcutt R. G. (1993). Afferent and efferent connections of the thalamic eminence in the axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. Neurosci. Lett. 149, 145–148 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90757-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni-Narla A., Getchell T. V., Getchell M. L. (1997). Differential expression of manganese and copper-zinc superoxide dismutases in the olfactory and vomeronasal receptor neurons of rats during ontogeny. J. Comp. Neurol. 381, 31–40 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970428)381:1%3C31::AID-CNE3%3E3.0.CO;2-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Dudley C. A., Moss R. L. (1999). Functional dichotomy within the vomeronasal system: distinct zones of neuronal activity in the accessory olfactory bulb correlate with sex-specific behaviors. J. Neurosci. 19, RC32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larriva-Sahd J. (2008). The accessory olfactory bulb in the adult rat: a cytological study of its cell types, neuropil, neuronal modules, and interactions with the main olfactory system. J. Comp. Neurol. 510, 309–350 10.1002/cne.21790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C. M., Kokay I. C., Grattan D. R. (2008). Male pheromones initiate prolactin-induced neurogenesis and advance maternal behavior in female mice. Horm. Behav. 53, 509–517 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D., Ogbogu U., Taylor B., Stafinski T., Menon D., Caulfield T. (2008). Stem cell clinics online: the direct-to-consumer portrayal of stem cell medicine. Cell Stem Cell 3, 591–594 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Brennan P., Widmayer P., S P. C., Maul-Pavicic A., Jäger M., et al. (2004). MHC class I peptides as chemosensory signals in the vomeronasal organ. Science 306, 1033–1037 10.1126/science.1102818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Ishii T., Mombaerts P., Zufall F., Boehm T. (2009). Structural requirements for the activation of vomeronasal sensory neurons by MHC peptides. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1551–1558 10.1038/nn.2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T., Lane A. P., Puche A. C., Ma W., Novotny M. V., Shipley M. T., et al. (2000). Ultrasensitive pheromone detection by mammalian vomeronasal neurons. Nature 405, 792–796 10.1038/35015572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepousez G., Valley M. T., Lledo P.-M. (2013). The impact of adult neurogenesis on olfactory bulb circuits and computations. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75, 339–363 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O., Kokaia Z. (2010). Stem cells in human neurodegenerative disorders–time for clinical translation? J. Clin. Invest. 120, 29–40 10.1172/JCI40543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo P.-M., Gheusi G. (2006). Adult neurogenesis: from basic research to clinical applications. Bull. Acad. Natl. Méd. 190, 385–402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati F., De Marchis S., Fasolo A., Peretto P. (2006). Neurogenesis in the caudate nucleus of the adult rabbit. J. Neurosci. 26, 609–621 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4371-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati F., De Marchis S., Parlato R., Gribaudo S., Schütz G., Fasolo A., et al. (2011). New striatal neurons in a mouse model of progressive striatal degeneration are generated in both the subventricular zone and the striatal parenchyma. PLoS ONE 6:e25088 10.1371/journal.pone.0025088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magavi S. S. P., Mitchell B. D., Szentirmai O., Carter B. S., Macklis J. D. (2005). Adult-born and preexisting olfactory granule neurons undergo distinct experience-dependent modifications of their olfactory responses in vivo. J. Neurosci. 25, 10729–10739 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak G. K., Enwere E. K., Gregg C., Pakarainen T., Poutanen M., Huhtaniemi I., et al. (2007). Male pheromone-stimulated neurogenesis in the adult female brain: possible role in mating behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1003–1011 10.1038/nn1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandairon N., Sacquet J., Jourdan F., Didier A. (2006). Long-term fate and distribution of newborn cells in the adult mouse olfactory bulb: influences of olfactory deprivation. Neuroscience 141, 443–451 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandairon N., Sultan S., Nouvian M., Sacquet J., Didier A. (2011). Involvement of newborn neurons in olfactory associative learning? The operant or non-operant component of the task makes all the difference. J. Neurosci. 31, 12455–12460 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2919-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Marcos A., Jia C., Quan W., Halpern M. (2005). Neurogenesis, migration, and apoptosis in the vomeronasal epithelium of adult mice. J. Neurobiol. 63, 173–187 10.1002/neu.20128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Marcos A., Ubeda-Bañón I., Deng L., Halpern M. (2000). Neurogenesis in the vomeronasal epithelium of adult rats: evidence for different mechanisms for growth and neuronal turnover. J. Neurobiol. 44, 423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Marcos A., Ubeda-Bañón I., Halpern M. (2001). Cell migration to the anterior and posterior divisions of the granule cell layer of the accessory olfactory bulb of adult opossums. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 127, 95–98 10.1016/S0165-3806(01)00106-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini S., Silvotti L., Shirazi A., Ryba N. J., Tirindelli R. (2001). Co-expression of putative pheromone receptors in the sensory neurons of the vomeronasal organ. J. Neurosci. 21, 843–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M., Osada T., Yoshida-Matsuoka J., Ikai A., Ichikawa M., Norita M., et al. (2002). A comparative immunocytochemical study of development and regeneration of chemosensory neurons in the rat vomeronasal system. Brain. Res. 946, 52–63 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)02823-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks J. P., Arnson H. A., Holy T. E. (2010). Representation and transformation of sensory information in the mouse accessory olfactory system. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 723–730 10.1038/nn.2546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisami E., Bhatnagar K. P. (1998). Vomeronasal organ in bats and primates: extremes of structural variability and its phylogenetic implications. Microsc. Res. Tech. 43, 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle F. T., Mirzadeh Z., varez-Buylla A. (2007). Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science 317, 1095–9203 10.1126/science.1144914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M., Inzirillo C., Shepherd G. M. (2007). Learning mechanism for column formation in the olfactory bulb. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 1:12 10.3389/neuro.07.012.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore M., Shepherd G. M. (2008). Dendritic action potentials connect distributed dendrodendritic microcircuits. J. Comput. Neurosci. 24, 207–221 10.1007/s10827-007-0051-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]