Abstract

Objective

Metabolic abnormalities, e.g., diabetes, are common among schizophrenia patients. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) regulates glucose/lipid metabolisms, and schizophrenia like syndrome may be induced by actions involving retinoid X receptor-α/PPAR-γ heterodimers. We examined a possible role of the PPAR-γ gene in metabolic traits and psychosis profile in schizophrenia patients exposed to antipsychotics.

Methods

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the PPAR-γ gene and a serial of metabolic traits were determined in 394 schizophrenia patients, among which 372 were rated with Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Results

SNP-10, -12, -18, -19, -20 and -26 were associated with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) whereas SNP-18, -19, -20 and -26 were associated with fasting plasma glucose (FPG). While SNP-23 was associated with triglycerides, no associations were identified between the other SNPs and lipids. Further haplotype analysis demonstrated an association between the PPAR-γ gene and psychosis profile.

Conclusion

Our study suggests a role of the PPAR-γ gene in altered glucose levels and psychosis profile in schizophrenia patients exposed to antipsychotics. Although the Pro12Ala at exon B has been concerned an essential variant in the development of obesity, the lack of association of the variant with metabolic traits in this study should not be treated as impossibility or a proof of error because other factors, e.g., genes regulated by PPAR-γ, may have complicated the development of metabolic abnormalities. Whether the PPAR-γ gene modifies the risk of metabolic abnormalities or psychosis, or causes metabolic abnormalities that lead to psychosis, remains to be examined.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Psychosis, Glucose, PPAR-γ gene

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic abnormalities, e.g., DM, are common among schizophrenia patients. DM may be induced by antipsychotics medications,1 or may occur before the antipsychotics exposure in a considerable number of schizophrenia patients.2 Positive syndrome of most schizophrenia patients can be relieved to some extents by antipsychotic treatments, but this is not the case for negative syndrome,3,4 suggesting that schizophrenia patients with severe negative syndrome may represent a subgroup with distinct biological features.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) belong to the superfamily of nuclear receptors (NRs), and play a central role in the transcriptional control of glucose and lipid regulation. The agonism of NRs has been used as a molecular strategy for treating diabetes and hyperglycemia.5 Three different human PPAR subtypes, namely PPAR-α, PPAR-β (also known as PPAR-δ) and PPAR-γ,6,7 have been identified. PPAR-γ is the most frequently studied NR, and is involved in the control of energy balance and lipid and glucose homeostasis.8 Several PPAR-γ gene knockout studies in mice have demonstrated glucose and lipid metabolism cross-talks between adipose tissue, muscle and liver, suggesting that PPAR-γ is important for retaining normal insulin sensitivity and whole-body glucose and lipid homeostasis.9,10 Also, genome-wide association and association studies have indicated a genetic contribution of the PPAR-γ gene in the development of type 2 DM and metabolic traits.11,12

The activation of PPAR-γ mediates anti-inflammation in the cardiovascular system and nervous system.13 PPAR-γ forms a heterodimer complex with retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα), which then binds to peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs) within the promoters of PPAR-γ-targeted genes.14,15 Retinoic acid receptors (RARs) are present in all parts of the cranial region, and delivery of retinoids is exquisitely controlled throughout the embryonic and fetal development.16 RARs act either alone or together with the heterodimeric partners. An in vitro experiment in adult human keratinocytes showed that endogenous retinoic acid RAR-RXR heterodimers are the major functional forms that regulate the retinoid-responsive elements,17 suggesting that an accurate regulation between PPAR-γ, RAR and RXR is needed to ensure a normal brain development and function. Because retinoid toxicity or deficit produces symptoms resembling schizophrenia,16 it is reasonable to deduce that genetic variants in the PPAR genes may affect the functioning of retinoid cascade and, thus, have profound implications in schizophrenia.

The objective of the study was to investigate a possible role of the PPAR-γ gene in metabolic traits and psychosis profile in schizophrenia patients in Taiwan.

METHODS

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yu-Li Hospital, Department of Health, Taiwan, file number YLH-93001. A total of 401 subjects (300 males and 101 females) meeting DSMIV criteria of schizophrenia and who had been exposed to antipsychotics treatment for more than 2 years, were recruited. None of the patients were exposed to psychiatric therapeutics other than antipsychotics except hypnotics when medically required. Medication for physical health problems was intervened in any form during the study period. The mean age of the study population was 49.3±9.9, ranging from 21 to 84 years. All eligible patients signed the informed consent form for blood donation and genetic analysis. At last, 394 good satisfactory DNA samples were obtained and used for genotyping. Psychosis profiles were evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Taiwan Chinese version, which includes subscales of positive syndrome, negative syndrome and general psychopathology.18 Three hundred and seventy two out of the 401 schizophrenia patients were successfully assessed using PANSS by board-certified psychiatrists. None of the patients were rated during acute psychosis. All patients examined in this study resided in a commodious environment.

Metabolic traits

BMI, waistline, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TGA), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), were measured on October 2004. Details of measurement of the indexes are summarized in supplement file.

Genotyping

The human PPAR-γ gene is located on chromosomal region 3p25.19 At least 7 human PPAR-γ mRNA splice variants have been found, each consists of exons 1 through 6 consecutively.20 The PPAR-γ protein exists in 2 isoforms-PPAR-γ1 with 477 amino acids and PPAR-γ2 with 505 amino acids. The PPAR-γ1 mRNAs are coded by 8 exons (A1, A2, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6), among which exon A1 and A2 are untranslated. The PPAR-γ2 mRNAs are encoded by 7 exons (exon B, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6), among which the additional 28 amino acids are encoded by exon B.21

Information of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the PPAR-γ gene in Han Chinese population (Beijing, China) and Japanese population (Tokyo, Japan) were retrieved from the HapMap database (phase II, 7 Jan 2007, http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Twenty TaqSNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.03 were selected using the Hapmap Tagger Program; 9 coding SNPs available during the research period were selected from dbSNP (Build 125) for genotyping. Detailed information of the SNPs, including chromosomal position, nucleotide location, exonic or intronic (based on PPAR-γ2 mRNA and protein encoded by exon B, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6), allelic variants and amino acid changes, are summarized in supplement file. The Sequenom MassARRAY® iPLEX Gold platform (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and calling software Typer were used for genotyping and signal analysis.

Statistical analysis

SNPs not deviated from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and ≥0.03 were analyzed using the Haploview™ program 4.1 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/scientific-community/science/programs/medical-and-population-genetics/haploview/haploview). General linear model (GLM) was used to estimate the contribution of each SNP, age, gender, the use of typical antipsychotics, and the use of atypical antipsychotics on metabolic indexes by applying the enter method. SNPs that possibly confer functionality or associated with genetic variants with functionality (i.e., SNPs significantly associated with metabolic indexes),22 were used to evaluate a role of the PPAR-γ gene in psychosis profile. The additive and dominant genetic effects of each haplotype on PANSS were tested against the other haplotypes (i.e., other haplotypes were merged and considered as one haplotype) in the same GLM with age, gender, the use of typical antipsychotics, and the use of atypical antipsychotics included. The code for additive effect (0, 1 or 2) in the data sheet was the frequency of the haplotype of interests. For dominant effects, the code was 1 when one haplotype of interests existed, and 0 when no haplotype of interest existed. After each haplotype was examined, those significantly contributed to PANSS either through additive or dominant effects, were further permutated with 10,000 iterations. The permutation tests randomly assigned the identification labels to the patients (each possessed a specific haplotype), creating a scenario where the dependent variable (i.e., PANSS) was not related to the PPAR-γ gene. The SAS program was used for the GLM statistical analysis and permutations.

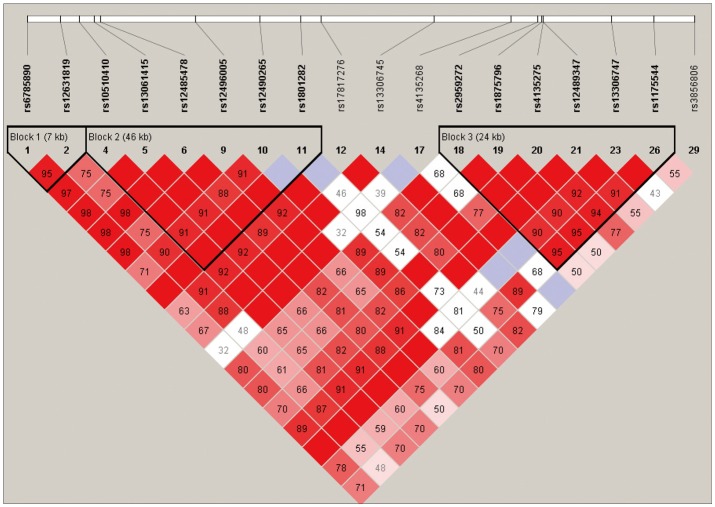

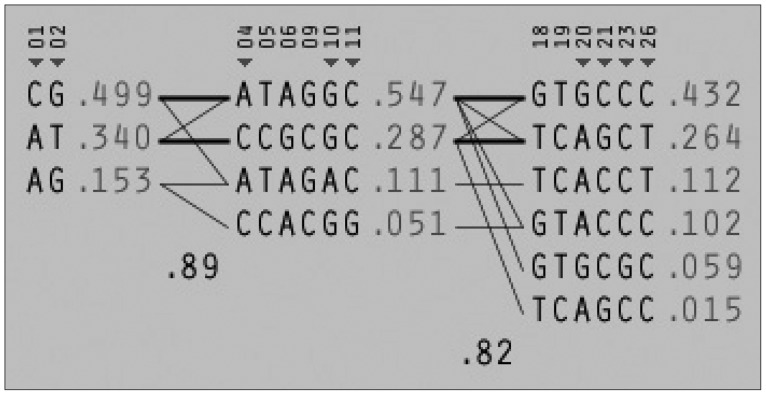

RESULTS

Among the 29 SNPs we examined, genotype distribution of 2 SNPs significantly deviated from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and 9 SNPs had MAF <0.03 (Supplementary Table 1, online). These 11 SNPs were excluded from statistical analysis to avoid a bias toward significance. Figure 1 shows the linkage disequilibrium (LD) strengths in D' between the 18 remained SNPs and haploblocks revealed by the Haploview program. The LD plot consisted 3 haploblocks: block-1 included SNP-1 (rs6785890, 5'UTR) and -2 (rs12631819, 5'UTR), spanning a 7 kb region; block 2 included SNP-4 (rs10510410, 5'UTR), -5 (rs13061415, 5'UTR), -6 (rs12485478, 5'UTR), -9 (rs12496005, 5'UTR), -10 (rs12490265, 5'UTR) and -11 (rs1801282, Pro12Ala, exon B), spanning a 46-kb region, followed by the unblocked SNP-12 (rs17817276, intron B), -14 (rs13306745, intron B) and -17 (rs4135268, intron B); block-3 included SNP-18 (rs2959272, intron 3), -19 (rs1875796, intron 3), -20 (rs4135275, intron 3), -21 (rs12489347, intron 3), -23 (rs13306747, Pro269Pro, exon 5) and -26 (rs1175544, intron 5), spanning a 24 kb region, followed by the independent SNP-29 (rs3856806, His449His, exon6). None of the SNPs were located at exon 1, intron 1, exon 2, intron 2 or exon 3. Further information on the haplotype frequencies and strengths between blocks are shown in Figure 2. The LD between block-1 and block-2 was 0.89, whereas that between block-2 and block-3 was 0.82. The unblocked SNP-12, -14 and -17 were located in intron B, suggesting that numerous historical recombinations occurred between intron B and block-2 and block-3. In terms of molecular evolution, block-1, block-2 and block-3 were possibly derived from the same DNA segment, while intron B was derived from DNA elsewhere.

Figure 1.

LD between valid SNPs. LD: Linkage disequilibrium, SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Figure 2.

LD between haploblocks. LD: Linkage disequilibrium.

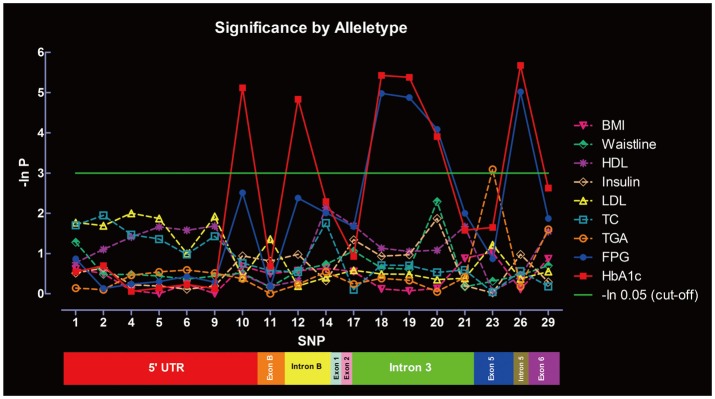

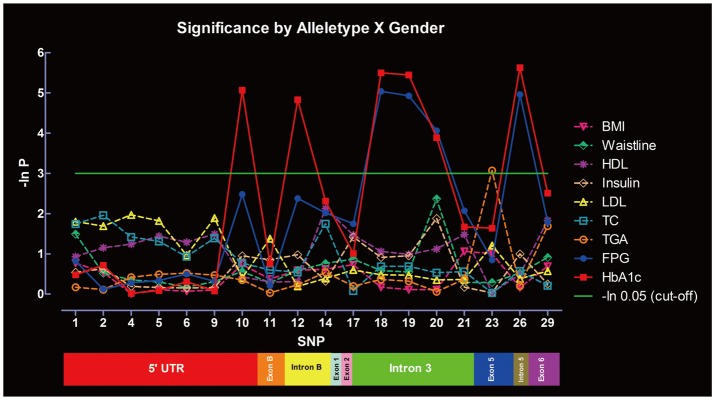

Significance of SNPs by allele distribution without considering gender interaction is summarized in Figure 3. SNP-10, -12, -18, -19, -20, and -26 were significantly associated with HbA1c, whereas SNP-18, -19, -20, and -26 were associated with FPG. Only SNP-23 was significantly associated with TGA. No associations were found between the SNPs and other metabolic indexes under the same parameters. Significance of SNPs by allele distribution when gender interaction was included is summarized in Figure 4. Similar associations were observed for HbA1c, FPG and TGA.

Figure 3.

Significance of the SNPs at the PPAR-γ gene in metabolic indexes evaluated by allele distribution, without gender interaction. P-values are shown in the form of minus natural logarithm (-In P). The green line is the significant level of -ln 0.05 (χ2=2.99). Rs serial numbers corresponding to the SNPs are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms, PPAR-γ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ.

Figure 4.

Significance of the SNPs at the PPAR-γ gene in metabolic indexes evaluated by allele distribution, with gender interaction. SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms, PPAR-γ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ, BMI: Body Mass Index, FPG: fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, TC: total cholesterol, TGA: triglycerides, LDL: low density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

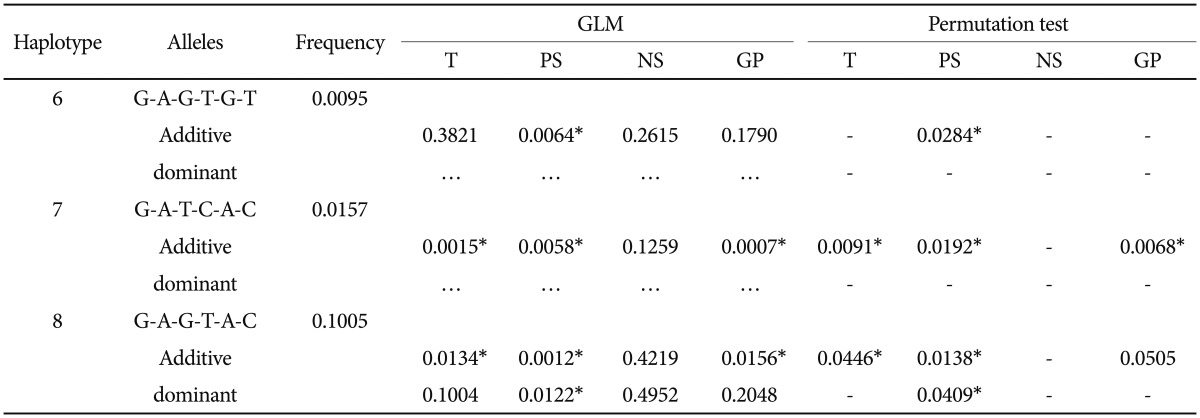

Six SNPs significantly associated with HbA1c including SNP-10, -12, -18, -19, -20, and -26, were selected to form haplotypes and used in the GLM and permutation tests. SNP-23 was tested separately because it was unrelated to glucose regulation in our statistical model. Eleven haplotypes were identified using the SAS program (Supplementary Table 2, online). Each haplotype was regressed with PANSS adjusted for age, gender, the use of typical antipsychotics and the use of atypical antipsychotics in the GLM. The results are summarized in Table 1. Haplotype 6 and 7 were significantly associated with one or more scales in additive mode only. Haplotype 6 was associated with positive syndrome (p=0.0064) but not with total scale (p=0.3821), negative syndrome (p=0.2615) or general psychopathology (p=0.1790). Haplotype 7 was associated with total scale (p=0.0015), positive syndrome (p=0.0058), and general psychopathology (p=0.0007), but not with negative syndrome (p=0.1259). Haplotype 8 was associated with total scale (p=0.0134), positive (p=0.0012) and general psychopathology (p=0.0156) in additive mode, but no with negative syndrome (0.4219); the haplotype also demonstrated an association with positive syndrome (0.0122) in dominant mode. These 3 haplotypes, with a summed up frequency of 12.6%, were then examined by permutation tests. All associations remained significant after 10,000 iterations, except for the association of haplotype 8 with general psychopathology (p=0.0505). The same alleles, namely allele G and A, existed in SNP-10 and 12 in the 3 haplotypes.

Table 1.

Statistical results for GLMs and permutation tests (10,000 iterations)

*significant p-values. T: total scale, PS: positive syndrome, NS: negative syndrome, GP: general psychopathology, GLM: General linear model

The regression of SNP-23 in PANSS demonstrated no evidence of association (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

SNP-11, the Pro12Ala nonsynonymous variant at exon B, is one of the most widely examined SNP at the PPAR-γ gene in studies investigating obesity related phenotypes, including insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.23,24 When this SNP was used to interpret the results, PPAR-γ2 mRNA or protein were presumed to play a major role over PPAR-γ1 mRNA or protein in the phenotype of interests, because exon B exists only in the PPAR-γ2 isoform. PPAR-γ1 mRNA is predominant in human tissues, but PPAR-γ2 mRNA only appears in human liver and adipose tissues. We found no evidence supporting a major role of the Pro12Ala at exon B (and thus PPAR-γ2) in maintaining a normal glucose level. Although the Pro12Ala at exon B has been concerned an essential variant in the development of obesity, that lack of association of the variant with metabolic traits in this study should not be treated as impossibility or a proof of error because other factors, e.g., genes regulated by PPAR-γ, may have complicated the development of metabolic abnormalities. SNP-23 (Pro269Pro), a synonymous variant at exon 5, was associated with TGA by allele distribution. Although a role of the PPAR-γ gene in lipid profile in schizophrenia patients remains inclusive, further investigation is worth performing, especially the lipid pathway concerning the Apolipoprotein E (APOE). The APOE gene is a schizophrenia gene.25,26 This gene is also a diabetic gene, which confers its risk at least partially through altering serum lipid levels.27 Importantly, APOE is transcriptionally regulated by PPAR-γ and liver X receptors (LXRs),28 which form obligate heterodimers with RXRs. Variations in the PPAR-γ gene may change the risk schizophrenia, psychosis syndrome or diabetes, through the subtle actions of PPAR-γ:RXR and LXR:RXR. For the haplotype effects on the PANSS scores, haplotype 6, 7 and 8 demonstrated a positive effect on positive syndrome although their frequencies were low. The common GA alleles of the two SNPs embracing exon B may, or are in linkage with genetic variants that affect the severity and long-term outcome of schizophrenia.

There are a few limitations in this study. First, our study subjects were schizophrenia patients undergoing long term antipsychotic treatment. The proclivity of antipsychotic drugs for metabolic disturbances, especially the second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics, have been extensively documented. For this reason, the associations identified in this study might be caused by the adverse effects of antipsychotics rather than the disease per se. Nevertheless, contributions of the antipsychotics were accounted for in the regression analysis. Third, haplotype 6 and 7 were of very low frequencies (<1% and 1.6%, respectively) and thus associations of these two genetic structures with PANSS relied on very small number of patients. Nevertheless, haplotype 8 was of relative high frequency (10.1%), suggesting the association was likely a true association.

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder in etiology, symptomology and treatment responses.29 Albeit metabolic abnormalities are associated with cognitive dysfunctions and brain abnormalities, so far, there have been limited evidences showing that metabolic abnormalities lead to specific mental disorders.30 The present study demonstrates a significant association of the PPAR-γ gene in altered glucose levels and psychosis profile in schizophrenia patients. Whether the PPAR-γ gene modifies the risk of metabolic abnormalities and psychosis, or causes metabolic abnormalities that lead to psychosis, remind to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Genotyping Center at Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, for their genotyping service.

Supplement

Supplemental Information for Materials and Methods

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TGA), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) were measured by using the Hitachi 7170 chemistry analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Insulin was examined by microparticle enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was examined by using the boronate affinity HPLC on PDQ Plus (Trinity Biotech, Kansas City, MO, USA).

FPG is influenced by type and quantity of food taken and thus demonstrates a broad variation within an individual. On the other hand, HbA1c is not influenced by daily glucose fluctuations, and thus reflects the average glucose metabolic status over a period of time.1

REFERENCE

1. Kilpatrick ES. Glycated haemoglobin in the year 2000. J Clin Pathol 2000;53:335-339.

Information of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used in this study. Valid SNPs used in statistical analysis are marked with #

Eleven haplotypes derived from 6 selected single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

- 1.Girgis RR, Javitch JA, Lieberman JA. Antipsychotic drug mechanisms: links between therapeutic effects, metabolic side effects and the insulin signaling pathway. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:918–929. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spelman LM, Walsh PI, Sharifi N, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Diabet Med. 2007;24:481–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter WT., Jr Clinical constructs and therapeutic discovery. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, Kissling W. Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:51–68. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans RM, Barish GD, Wang YX. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreyer C, Krey G, Keller H, Givel F, Helftenbein G, Wahli W. Control of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1992;68:879–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PS, Savory R, Barratt P, Bell AR, Gray TJ, Jenkins NA, et al. Chromosomal localisation, inducibility, tissue-specific expression and strain differences in three murine peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor genes. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.219_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemberger T, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a nuclear receptor signaling pathway in lipid physiology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:335–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He W, Barak Y, Hevener A, Olson P, Liao D, Le J, et al. Adipose-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma knockout causes insulin resistance in fat and liver but not in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15712–15717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536828100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koutnikova H, Cock TA, Watanabe M, Houten SM, Champy MF, Dierich A, et al. Compensation by the muscle limits the metabolic consequences of lipodystrophy in PPAR gamma hypomorphic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14457–14462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336090100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CH, Lu ML, Kuo PH, Chen PY, Chiu CC, Kao CF, et al. Gender differences in the effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2 gene polymorphisms on metabolic adversity in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetes Genetics Initiative of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Lund University, and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research. Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, Burtt NP, de Bakker PI, et al. Genomewide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daynes RA, Jones DC. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:748–759. doi: 10.1038/nri912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ijpenberg A, Jeannin E, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Polarity and specific sequence requirements of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)/retinoid X receptor heterodimer binding to DNA. A functional analysis of the malic enzyme gene PPAR response element. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20108–20117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature. 1992;358:771–774. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman AB. Three independent lines of evidence suggest retinoids as causal to schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7240–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao JH, Durand B, Chambon P, Voorhees JJ. Endogenous retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-retinoid X receptor (RXR) heterodimers are the major functional forms regulating retinoid-responsive elements in adult human keratinocytes. Binding of ligands to RAR only is sufficient for RAR-RXR heterodimers to confer ligand-dependent activation of hRAR beta 2/RARE (DR5) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3001–3011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng JJ, Ho H, Chang CJ, Lane HY, Hu HG. Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS): Establishment and reliability study of a mandarin Chinese language version. Chin Psychiaty. 1996;10:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene ME, Blumberg B, McBride OW, Yi HF, Kronquist K, Kwan K, et al. Isolation of the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma cDNA: expression in hematopoietic cells and chromosomal mapping. Gene Expr. 1995;4:281–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClelland S, Shrivastava R, Medh JD. Regulation of translational efficiency by disparate 5’ UTRs of PPARgamma splice variants. PPAR Res. 2009;2009:193413. doi: 10.1155/2009/193413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspé E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, et al. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18779–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu MC, Kraft P, Epstein MP, Taylor DM, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ, et al. Powerful SNP-set analysis for case-control genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:929–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, Lindgren CM, Vohl MC, Nemesh J, et al. The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:76–80. doi: 10.1038/79216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonjes A, Scholz M, Loeffler M, Stumvoll M. Association of Pro12Ala polymorphism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with Pre-diabetic phenotypes: meta-analysis of 57 studies on nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2489–2497. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen NC, Bagade S, McQueen MB, Ioannidis JP, Kavvoura FK, Khoury MJ, et al. Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in schizophrenia: the SzGene database. Nat Genet. 2008;40:827–834. doi: 10.1038/ng.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu MQ, St Clair D, He L. Meta-analysis of association between ApoE epsilon4 allele and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anthopoulos PG, Hamodrakas SJ, Bagos PG. Apolipoprotein E polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of 30 studies including 5423 cases and 8197 controls. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chawla A, Boisvert WA, Lee CH, Laffitte BA, Barak Y, Joseph SB, et al. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkpatrick B, Galderisi S. Deficit schizophrenia: an update. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:143–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yates KF, Sweat V, Yau PL, Turchiano MM, Convit A. Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognition and brain: a selected review of the literature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2060–2067. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.252759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Information of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used in this study. Valid SNPs used in statistical analysis are marked with #

Eleven haplotypes derived from 6 selected single nucleotide polymorphisms