Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the level of Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) in adults of Chandigarh and to correlate the dental caries in these individuals with their S. mutans titers.

Materials and Methods:

Salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans, using Dentocult SM commercial kits were estimated in 200, 25-35 year old adults (males and females). Streptococcus mutans were detected in 87% of the study sample. Score 2, representing 105-106 CFU/ml (Colony Forming Unit) of saliva was found to be most prevalent, i.e. in 80 of 200 adults, followed by score 1, depicting S mutans with <105 CFU/ml, in 56 of 200 adults and score 3, with bacterial titer >106 CFU/ml in 38 of 200 adults.

Results:

Dental caries, recorded using Møller's index, was found to be maximum in individuals with score 3, followed by score 2,1 and 0, thereby showing a positive correlation of dental caries with increasing titers of S. mutans. This correlation was statistically highly significant in males with figures as 8.73 decayed surfaces at score 2 rising to 17.38 at score 3. The mean of DMFT was higher among females than in the males in the present study.

Conclusion:

The split up data in males and females, showed a positive association between caries experience and salivary S. mutans scores. The results of the study will serve as a baseline data for future planning of preventive programs in adults.

Keywords: Adults, dental caries, dentocult SM kits, Streptococcus mutans

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus mutans has been implicated as one of the major etiological factor of dental caries.[1,2] Tooth surfaces colonized with S. mutans are at a higher risk for developing caries.[3] In populations with a relatively high caries experience, a positive association between salivary levels of S. mutans and dental caries experience have been reported.[4,5] Individuals with high levels of S. mutans also develop more coronal and root caries in temporary and permanent restorations than do individuals in the same population with lower concentration of S. mutans.[6,7] Salivary levels of S. mutans are directly related to the number of tooth sites colonized[8] and to their proportion in dental plaque.[9]

Majority of the studies on frequency distribution of S. mutans and its correlation with dental caries have been carried out on children[3,10] and a few on adolescents[11,12,13] while the data on adults are sparse.[13,14,15,16] Saliva has been used to monitor the total oral load of these micro-organisms.[10] In adults the mechanism of pathogenesis of dental caries is much more complex than in children. Disregarding the level (concentration) of S. mutans, data from research prove that the number of carious lesions per tooth in the adult population is rather higher. Explanations of these data point to the following: Gingival recession, lowered saliva secretion, motor function of the masticatory system, wearing a dental prosthesis, poor oral hygiene, and inordinate dental examination.[17] Thus, more information is needed regarding the distribution of S. mutans and correlation of levels of S. mutans with caries in adults. The present study was planned in adult population of Chandigarh, India (i) to determine the S. mutans levels in their stimulated saliva and (ii) to correlate the dental caries in these individuals with their S. mutans titers separately in both the males and females.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry at Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of PGIMER, Chandigarh. A written informed consent was obtained from the selected participants.

Study participants

Households of the study subjects residing in different sectors of Chandigarh were visited by the main author. Individuals aged between 25-35 years were short listed and explained the purpose of the study. The sample size necessary for the study was calculated on the basis of prevalence of dental caries in adults which was obtained on the basis of pilot study conducted on 50 subjects and consulting a statistician. The inclusion criteria were that the participants were dentate, had not suffered from any systemic debilitating disease and were not taking or had taken antibiotics in the last 3 months. The individuals undergoing orthodontic treatment, with dentures, crowns or bridges were not included in the study. The willing participants were thus randomly selected so as to make a study group of 200 adults with equal number of females and males.

The selected individuals were instructed not to eat/drink, brush their teeth, use a mouth wash, or smoke 1 h prior to their appointment. The households were revisited by the author (PP) at the appointed time and recording of dental caries and collection of saliva sample was carried out. Prior to the start of the study the recorder (PP) was trained by repeated sessions of calibration carried out in the department of the institute.

Recording of dental caries

The DMFT recording was done by a single calibrated examiner using mouth mirror and probe, with the participant seated on an ordinary chair in natural day light, facing away from direct sunlight. Møller's index[18] for dental caries recordings was used to record DMFT and DMFS as it records the initial carious lesions and initiation of dental caries is associated with the presence of S. mutans. Recordings were made on the Unilever dental proforma using standardized Hu-Friedy dental probes with a tip diameter of 45 microns so that any remineralization is not disturbed that could have happened with a finer tip probe, i.e., 18 μm, as used by I. J. Moller.

Estimation of salivary levels of S. mutans

Subsequently, in the same sitting, the salivary sample collection for the estimation of levels of S. mutans was carried out, using a commercially available kit, Dentocult SM (Orion Diagnostica Co. Ltd, Helsinki, Finland) introduced by Jensen and Bratthall.[19] Each participant was given a paraffin pellet (provided in the kit), to be chewed upon for 1 min, and was instructed to swallow the stimulated saliva after the removal of the pellet. A Dentocult SM–Strip was rotated ten times on the participant's tongue and was withdrawn gently with the teeth apart and lips closed to obtain a thin layer of saliva on the strip. This act was rehearsed in each individual before the actual procedure. The contaminated strip was immediately transferred into a glass vial containing the MSB agar medium which contained mitis salivarius agar with sucrose, bacitracin, and potassium tellurite.

The vials containing Dentocult SM strips were coded and were transported within an hour of collection to the laboratory in an upright position, by placing them in their original boxes. In the laboratory the vials were given another code by one of the authors, in order to make it a blind study. The screw cap of the vials was opened by quarter of a turn so as to release any gas which could form during incubation. The vials were incubated at 37° centigrade for 48 h.

After incubation the strips were carefully removed from the vials with the help of tweezers and air dried. The colony density on the strips was compared with the standard interpretation chart (provided by the manufacturer in the kit) and the grading of the strips was done as score 0, 1, 2, or 3 by observing them with the naked eye. Strip mutans score 0 depicts <104 CFU/ml, score 1 corresponds to <105 CFU/ml, Score 2 refers to 105-106 CFU/ml, and Score 3 indicates >106 CFU/ml. The formula of “when in doubt, score less” was followed, in doubtful cases one score lower than the observed score was recorded to ensure standardization. After the recording, the strips were packed in plastic bags and sent for incineration.

Statistical analysis

The recorded data were transferred to an MS-excel sheet and statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 13.0 for Windows). The data were statistically analyzed using ANOVA test. Dental caries experience was correlated with S. mutans levels using Pearson's correlation coefficient. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

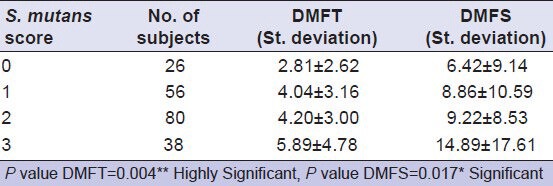

The frequency distribution of S. mutans in 200 adults, separately in females and males is presented in Tables 1–3, respectively. Out of a total of 200 participants, 174 (87%) had S. mutans titers equivalent to score 1, 2, and 3. The highest number of individuals (80) had score 2, followed by Score 1 (34) and score 3 (38). The proportion of individuals with S. mutans score of 0 was least (26). The prevalence of S. mutans was significantly higher in females (92%) than in males (82%).

Table 1.

Correlation between dental caries experience and salivary S. mutans scores

Table 3.

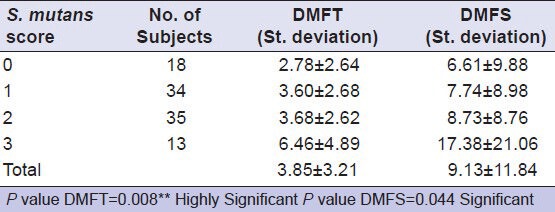

Correlation between dental caries experience and salivary scores of S. mutans in females

The salivary levels of S. mutans of the adults were related to their DMFT/S scores. It was found that overall DMFT/S was lower when the levels of S. mutans was less and increased with the increase in bacterial titers. From score 1 to 2, the increase in the dental caries was not so marked, whereas there was statistically significant increase of decayed teeth/surfaces as the titers increased to score 3. This correlation was statistically highly significant in males with figures as 8.73 decayed surfaces at score 2 rising to 17.38 at score 3.

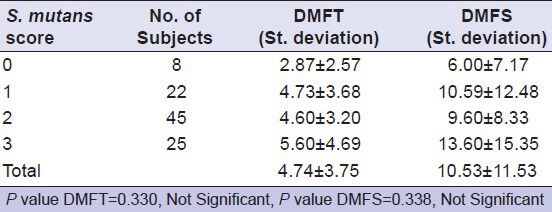

In males, the difference in the mean DMFT/S between scores 0 and 3 was found to be statistically significant at 5% level [Table 2]. In females also a similar increase was seen, except from score 1 to 2, where there was a marginal decrease of 1 DMFS. The mean of DMFT was higher among females (4.74) than in the males (3.85) in the present study. In females, the difference between the groups was found to be statistically not significant (P > 0.5) [Table 3].

Table 2.

Correlation between dental caries experience and salivary scores of S. mutans in males

DISCUSSION

Oral disease is a major public health problem due to the high prevalence in all regions of the world and the greatest impact on the socially marginalized populations. Therefore, the evaluation of caries risk is most important. It gives an opportunity to improve hygiene, diet, and implement preventive measures in an exposed population.[20]

Some authors compared the results of Strip mutans method with that of conventional MSB plating method and reported a highly significant correlation between the two (contingency coefficient = 0.76).[19] They also compared the number of S. mutans colony forming units per ml of saliva (CFU/ml) obtained on two consecutive occasions by using strip mutans method and observed a contingency coefficient of 0.80 thereby establishing reliability of the method.[19]

In the present study the decayed component comprised 99.04% of DMFT. It may be of significance to know that in the DMFT/S components, the filled component was only 0.96% depicting a total neglect of dental restorative care which is in accordance with a study in Sweden.[17] On the other hand, this factor of untreated carious lesions is advantageous as it does not mask the cumulative effect of correlation of the S. mutans titers with the spread of dental caries.

The results are in accordance with the studies conducted by some other authors who reported a positive correlation between the concentration of mutans streptococci in saliva and dental caries.[9,14] Individuals with lower concentrations showed a significantly lower mean number of decayed surfaces compared with the individuals with higher concentrations of mutans streptococci in their saliva.[21] Results of a recent study conducted in Japan showed that high levels of mutans streptococci (MS) correlated with the onset of primary and secondary caries, with odds ratios of 2.34 and 2.22, respectively.[22] According to some other study reports, levels of MS were not associated with high caries experience which is contradictory to the results of the present study.[23,24]

Considering the relation between DMFT and gender, the mean of DMFT was higher among females than in the males in the present study. When dental caries rates were reported by gender in the dental literature, females were found to exhibit typically higher prevalence rates than males. This finding is generally true for diverse cultures and for a wide range of chronological periods.[25,26,27] A high caries rate in females can be attributed to frequent snacking and hormonal imbalance during events such as puberty, menstruation, and pregnancy.[27]

A cross-sectional study design was used in the present study to determine the correlation between S. mutans and dental caries experience like several other studies. But a single saliva sample would record the microbial counts at one particular point of time and its well understood that dental caries develops over a considerable period of time, during which bacterial counts would fluctuate in response to the changing oral environment.[28]

CONCLUSION

Longitudinal studies, where microbial samples are taken at regular intervals would help to study the variation in counts of microorganisms. However, the results of this study will add to the existing data on the gender differences in caries, which can be used for planning preventive programs in adults, to reduce the reservoir of S. mutans and hence prevent its transmission to the infants and adults.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Hamada S, Slade HD. Biology, Immunology and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:331–84. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.2.331-384.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loesche WJ. The role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:353–80. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loesche WJ, Eklund S, Earnest R, Burt B. Longitudinal investigation of bacteriology of human fissure decay; epidemiological studies in molars shortly after eruption. Infect Immun. 1984;46:765–72. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.3.765-772.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emilson CG, Krasse B. Support for an implication of the specific plaque hypothesis. Scand J Dent Res. 1985;93:96–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1985.tb01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koga-Ito CY, Martins CA, Balducci I, Jorge AO. Correlation among mutans streptococci counts, dental caries, and IgA to Streptococcus mutans in saliva. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18:350–5. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242004000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thenisch NL, Bachmann LM, Imfeld T, Leisebach MT, Steurer J. Are mutans streptococci detected in preschool children a reliable predictive factor for dental caries risk? A systematic review. Caries Res. 2006;40:366–74. doi: 10.1159/000094280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preza D, Olsen I, Aas JA, Willumsen T, Grinde B, Paster BJ. Bacterial profiles of root caries in elderly patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2015–21. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02411-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Togelius J, Kristoffersson K, Andersson H, Bratthall D. Streptococcus mutans in saliva: Intra-individual variations and relation to number of colonized sites. Acta Odontol Scand. 1984;42:157–63. doi: 10.3109/00016358408993867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenander-Lumikari M, Loimaranta V. Saliva and Dental Caries. Adv Dent Res. 2000;14:40–7. doi: 10.1177/08959374000140010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beighton D, Rippon HR, Thomas HE. The distribution of Streptococcus mutans serotypes and dental caries experience in a group of 5-8-year-old English school children. Br Dent J. 1987;162:103–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beighton D, Manji F, Baelum V, Fejerskov O, Johnson NW, Wilton JMA. Associations between Salivary Levels of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, Lactobacilli and caries experience in Kenyan Adolescents. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1242–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680080601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedge PP, Ashok BR, Ankola VA. Dental caries experience and salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in 13-15 years old children of Belgaum city, Karnataka. J Indian Soc Pedo Prev Dent. 2005;23:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.16022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim HH, Yoo SY, Kim KW, Kook JK. Frequency of Species and Biotypes of Mutans Streptococci Isolated from Dental Plaque in Adolescents and Adults. J Bacteriol Virol. 2005;35:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salonen L, Allander D, Bratthall D, Hellden L. Mutans Streptococci, oral hygiene and caries in an adult Swedish population. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1469–75. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batoni G, Ota F, Gheraldi S, Senesi S, Barnini S, Freer G, et al. Epidemiological survey of Streptococcus mutans in a group of adult patients living in Pisa (Italy) Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:2:238–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00144807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishikawara F, Katsumura S, Ando A, Tamaki Y, Nakamura Y, Sato K, et al. Correlation of cariogenic bacteria and dental caries in adults. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:245–51. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apostolska S, Rendzova V, Ivanovski K, Peeva M, Elencevski S. Presence of caries with different levels of oral hygiene. Prilozi. 2011;32:269–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Möller IJ. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of the incipient carious lesion. Adv Fluorine Res. 1966;4:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen B, Brathall D. A new method for the estimation of Mutans Streptococci in human saliva. J Dent Res. 1989;68:468–71. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, McGrath C. Oral health status of homeless people in Hong Kong. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:150–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alaluusua S, Renkonen OV. Streptococcus mutans establishment and dental caries experience in children from 2-4 years old. Scand J Dent Res. 1983;91:453–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1983.tb00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito A, Hayashi M, Hamasaki T, Ebisu S. How regular visits and preventive programs affect onset of adult caries. J Dent Res. 2012:52S–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034511435701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giacaman RA, Araneda E, Padilla C. Association between biofilm-forming isolates of mutans streptococci and caries experience in adults. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:550–4. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Palenstein Helderman WH, Matee MI, van der Hoeven JS, Mikx FH. Cariogenicity depends more on diet than the prevailing mutans streptococcal species. J Dent Res. 1996;75:535–45. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashim BA, Noor MA, Chindia ML. Oral health status among Kenyans in rural arid setting: Dental; caries experience and knowledge on its causes. East Afr Med J. 2006;83:100–5. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v83i2.9396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukacs JR, Largaespada LL. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and “life-history” etiologies. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18:540–55. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farsi N. Dental caries in relation to salivary factors in Saudi population groups. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tukia-Kulmala H, Tenovuo J. Intra- and inter-individual variation in salivary flow rate, buffer effect, Lactobacilli and mutans streptococci among 11to 12-year old school children. Acta Odontol Scand. 1993;51:31–7. doi: 10.3109/00016359309041145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]