Abstract

Long-term cardiovascular complications in metabolic syndrome are a major cause of mortality and morbidity in India and forecasted estimates in this domain of research are scarcely reported in the literature. The aim of present investigation is to estimate the cardiovascular events associated with a representative Indian population of patients suffering from metabolic syndrome using United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. Patient level data was collated from 567 patients suffering from metabolic syndrome through structured interviews and physician records regarding the input variables, which were entered into the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. The patients of metabolic syndrome were selected according to guidelines of National Cholesterol Education Program – Adult Treatment Panel III, modified National Cholesterol Education Program – Adult Treatment Panel III and International Diabetes Federation criteria. A projection for 10 simulated years was run on the engine and output was determined. The data for each patient was processed using the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine to calculate an estimate of the forecasted value for the cardiovascular complications after a period of 10 years. The absolute risk (95% confidence interval) for coronary heart disease, fatal coronary heart disease, stroke and fatal stroke for 10 years was 3.79 (1.5–3.2), 9.6 (6.8–10.7), 7.91 (6.5–9.9) and 3.57 (2.3–4.5), respectively. The relative risk (95% confidence interval) for coronary heart disease, fatal coronary heart disease, stroke and fatal stroke was 17.8 (12.98–19.99), 7 (6.7–7.2), 5.9 (4.0–6.6) and 4.7 (3.2–5.7), respectively. Simulated projections of metabolic syndrome patients predict serious life-threatening cardiovascular consequences in the representative cohort of patients in western India.

Keywords: UKPDS risk engine, cardiovascular complications, metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is an array of lipid and nonlipid factors of metabolic origin related to defects in insulin sensitivity that lead to a high risk for the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Various prospective analyses have reported that the metabolic syndrome is associated with an approximate twofold increase in CVD[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In addition, people with metabolic syndrome have a fivefold greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes[7,14,16]. In a community study, middle-aged people of either sex with metabolic syndrome were 1.5-2 times more vulnerable to get coronary heart disease (CHD)[17]. Moreover, metabolic syndrome is more prevalent in aged individuals, affecting half of adults aged 60 years and over[9].

The National Cholesterol Education Program – Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) has laid down guidelines for defining a typical patient of metabolic syndrome. As per NCEP ATP III definition, metabolic syndrome is identified when three or more of the following five components are present: (1) elevated waist circumference (WC), (2) elevated triglyceride (TG), (3) reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, (4) elevated blood pressure (BP) and (5) elevated fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or already diagnosed to have diabetes mellitus (DM). Long-term cardiovascular complications in metabolic syndrome are a major cause of mortality and morbidity in India and forecasted estimates in this domain of research are scarcely reported in literature. Metabolic syndrome, first defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1998[18], has been christened into a new definition by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in 2005[19]. This gives an important aspect of the NCEP-ATPIII definition (NCEP 2001) and updated in 2005[20]. The major variables in the current definitions include abdominal obesity, BP elevation, dyslipidaemia and hyperglycaemia with varying cut-off levels.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk engine is most widely known and used for determination of long-term cardiovascular events. Various investigators have predicted the risk score specifically for diabetic patients, either newly diagnosed patients or those already receiving treatment[21,22,23,24,25] across the globe. However, a couple of studies from India have employed UKPDS risk engine[1]. It forecasts the risk of vascular diseases for 10 years. It predicts the absolute CHD risk using traditional risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), age, sex, smoking, systolic BP, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, atrial fibrillation, ethnicity, duration of diabetes and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)[26]. Hence, in the present investigation, we estimated the long-term cardiovascular events associated with a representative Indian population of patients suffering from metabolic syndrome.

The study protocol was approved by the scientific committee of Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Poona College of Pharmacy, Pune, India, Institutional human ethics committee and permission was granted by the governing authorities of Agarwal hospital, Khenat hospital and Dhekane clinic, Pune to interact and inquire information regarding BMI, age, sex, smoking, systolic BP, total cholesterol HDL-cholesterol, atrial fibrillation, ethnicity, duration of diabetes and HbA1c from the patients attending the outpatient departments of these hospitals. If the patients were unable to provide the required information, the concerned physician was consulted or the patient records were used as the source of the data. The patients agreed to participate in the study after filling a well-defined informed consent form in local language (Marathi). A written permission was granted by UKPDS, UK authorities to carry out this academic noncommercial research using UKPDS risk engine within the aegis of the university.

Patient level data was collated from 567 diabetic patients suffering from metabolic syndrome through structured interviews and physician records regarding the input variables, which were entered into the UKPDS risk engine. The patients of metabolic syndrome were selected according to guidelines of NCEP ATP III, modified NCEP ATP III and IDF criteria. Projections for 10 simulated years were run on the engine and the output determined. The data for each patient was processed using the UKPDS risk engine to calculate an estimate of the forecasted value for the cardiovascular complications after a period of 10 years.

The UKPDS defines diabetes as follows: clinician diagnosed diabetes, subsequently confirmed by two FPG greater than 6 mmol/l on two occasions. The UKPDS defines myocardial infarction by the WHO clinical criteria (either total cholesterol and HDL enzyme rise or pathological Q-wave in ECG). The risk engine cardiac endpoint is CHD, defined by either myocardial infarction (fatal or nonfatal) or sudden death. The risk engine stroke endpoint is stroke as defined by the UKPDS: either death attributed to stroke, or stroke with symptoms or signs persisting for more than 1 month. The risk engine version 2 calculates the risk that first CHD is fatal within 6 months. This will slightly underestimate the total rate of fatal CHD. Later versions of the risk engine will calculate total risk of fatal CHD. The same remarks apply to fatal stroke.

As per NCEP ATP III definition, metabolic syndrome was identified when three or more of the following five components were present: (1) elevated WC (WC ≥102 cm in men, ≥88 cm in women), (2) elevated TG (TG ≥150 mg/dl, ≥1.7 mmol/l), (3) reduced HDL-cholesterol (HDL ≤40 mg/dl or ≤1.03 mmol/l in men, ≤50 mg/dl or ≤1.29 mmol/l in women), (4) elevated BP (BP ≥130/85 mmHg) and (5) elevated FPG (FPG ≥100 mg/dl or ≥5.6 mmol/l) or already diagnosed to have DM.

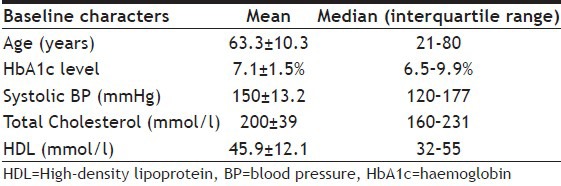

Baseline characteristics are presented as means, median (interquartile range). The estimated 10-year first CHD risk was calculated for each participant using the UKPDS algorithms. Calibration of the model was visually checked by plotting the predicted probabilities estimated by the prediction models against the observed proportion of first CHD events UKPDS and fatal CHD events score. Participants were grouped into CHD and fatal CHD depends on quintiles of predicted CHD risk within 10 years of follow-up.

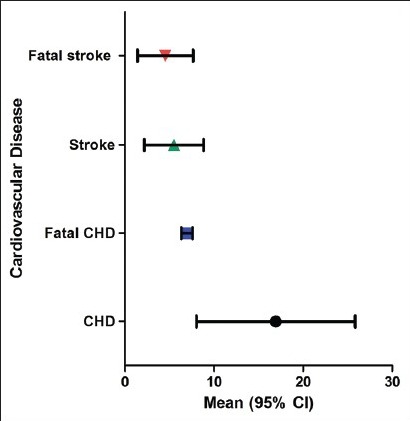

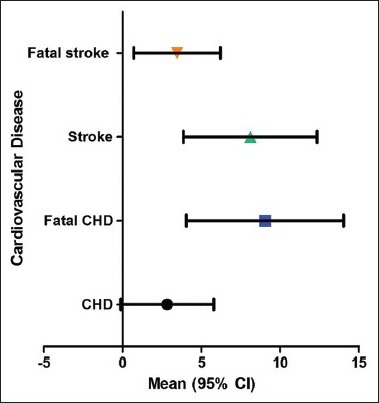

In the present investigation, figs. 1 and 2 depicted that various vascular parameters such as systolic BP, total cholesterol and HDL cause significant progression of disease and finally lead to morbidity and mortality. A 10-year forecasted estimate of the cardiovascular events governs higher risk of disease in patients with metabolic syndrome than normal people. The UKPDS risk engine output consisted of estimates of absolute and relative risk of CHD (congestive heart disease), fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke after a period of 10 years. The baselines characteristics are represented in Table 1. The baseline characteristics correlate with the symptoms of metabolic syndrome patients. The input variables for the risk engine are present age, sex, presence of atrial fibrillation, ethnicity, smoking status, HbA1c, systolic BP, total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol. The data for each individual patient was processed using the UKPDS risk engine to calculate an estimated numerical value of the forecasted value of long-term cardiovascular complications after a period of 10 years in the metabolic syndrome patients. The absolute risk (fig. 1, 95% confidence interval, CI) for CHD, fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke for 10 years was 3.79 (1.5–3.2), 9.6 (6.8–10.7), 7.91 (6.5–9.9) and 3.57 (2.3–4.5), respectively. The relative risk (fig. 2, 95% CI) for CHD, fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke was 17.8 (12.98–19.99), 7 (6.7–7.2), 5.9 (4.0–6.6) and 4.7 (3.2–5.7), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Predicted absolute risk of cardiovascular disease over 10 years. Predicted absolute risk over period of 10 year with 95% confidence intervals of cardiovascular disease including CHD, Fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke using UKPDS risk engine.

Fig. 2.

Predicted relative risk of cardiovascular disease over 10 years. Predicted relative risk over period of 10 year with 95% confidence intervals of cardiovascular disease including CHD, fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke using UKPDS risk engine.

TABLE 1.

BASELINE DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF 567 PATIENTS

Metabolic syndrome is a disorder of energy utilisation and storage reflected by elevated levels of BP, plasma glucose, serum TGs with decreased low HDL cholesterol that increases risk of CVDs; it also increases the risk of diabetes in patients[4,7,14,27,28]. At present, 25% of the world population is suffering from metabolic syndrome. The prevalence of disease varies across the globe. In India, prevalence rates of metabolic syndrome during 2010 were 35.8% (NCEP ATP III), 45.3% (modified NCEP ATP III) and 39.5% (IDF criteria)[29]. In the US, metabolic syndrome is more common in males than in females. In India, females are more prone to metabolic syndrome when compared with men[30,31]. The risk factors for metabolic syndrome are increasing age, gender, race, ethnicity and sedentary lifestyle and diabetes in parents. Indians have a higher tendency to develop cardiovascular abnormalities as compared with other Asian ethnic groups. Using modified NCEP ATP III criteria, a study had reported that age adjusted prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher in Indians among different Asian ethnic groups[32].

To our knowledge, this is a pioneer study in India that uses UKPDS risk engine to predict long-term cardiovascular risk factors in patients with metabolic syndrome. The inputs required by the engine are all readily measured in clinical practice, and routinely reported in research for maximum applicability. UKPDS outcomes model has been incorporated in the UKPDS Risk Engine software, which is available to noncommercial users without charge from UKPDS website (http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/riskengine/download.php)[19].

UKPDS was generally conducted in the White, Afro-Caribbean or Asian-Indian ethnic group patients[23]. The western Indian population of metabolic syndrome patients from Pune, who have been included in the study, may be considered to be a representative of the general Asian-Indian population. The present investigation gives a clear picture of long-term cardiovascular events in metabolic syndrome patients, that is the absolute risk for CHD, fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke for 10 years was 3.79, 9.6, 7.91 and 3.57 years, respectively. Whereas the relative risk for CHD, fatal CHD, stroke and fatal stroke was 17.8, 7, 5.9 and 4.7 years, respectively. UKPDS risk engine simulates risk of cardiovascular events in patients for 10 years.

Sedentary lifestyle has a greater impact in the development of metabolic syndrome. The findings of the present investigation are in accordance with the findings of Kothari et al. who used a similar risk engine to evaluate the risk of stroke in 4549 type II diabetes patients in the UKPDS[23]. Moreover, a similar study has been published by Simmons et al. who examined the performance of the UKPDS Risk Engine (version 3) and the Framingham risk equations in estimating CVD incidence in various populations[32]. The forecasted risk of long-term cardiovascular events will contribute to a better control of the metabolic disorders. Measures need to be taken to alleviate the long-term CVDs and to halt the progression of cardiovascular complications and mortality[33].

The present study provides credence to the previous studies carried out by Ghosh et al. and Ravikiran et al. who demonstrated that metabolic syndrome poses serious threat to patients[1,29]. Moreover, findings of Ghosh et al. in type 2 DM patients accord the findings of the present investigation as UKPDS risk engine successfully predicted the CVDs in type 2 diabetes in our previous investigation[1]. The present study on metabolic syndrome patients reiterates a similar trend for predicting the risk of CVDs in type 2 diabetes and warrants urgent measures to halt the progression of metabolic syndrome among all age groups to alleviate long-term cardiovascular perturbations. Simulated projections of metabolic syndrome patients predict serious life-threatening cardiovascular consequences in the representative cohort of metabolic syndrome patients in western India.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. S. S. Kadam, Vice-Chancellor and Dr. K. R. Mahadik, Principal, Poona College of Pharmacy, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune, India, for providing necessary facilities to carry out the study. The authors are also thankful to the UKPDS risk engine development team and the UKPDS outcomes model development team to grant the permission to use these engines for noncommercial academic research purpose.

Footnotes

Shivakumar, et al.: Estimation Cardiovascular Events by Using UKPDS Risk Engine

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghosh P, Kandhare AD, Raygude KS, Kumar VS, Rajmane AR, Adil M, et al. Determination of the long term diabetes related complications and cardiovascular events using UKPDS risk engine and UKPDS outcomes model in a representative western Indian population. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2012;2:S642–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffner SM, Valdez RA, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Morales PA, Stern MP. Prospective analysis of the insulin-resistance syndrome (syndrome X) Diabetes. 1992;41:715–22. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandhare AD, Bodhankar SL, Singh V, Mohan V, Thakurdesai PA. Antiasthmatic effects of type-A procyanidine polyphenols from cinnamon bark in ovalbumin-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in laboratory animals. Biomed Aging Pathol. 2013;3:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil MV, Kandhare AD, Bhise SD. Antiarthritic and antiinflammatory activity of Xanthium srtumarium L. ethanolic extract in Freund's complete adjuvant induced arthritis. Biomed Aging Pathol. 2012;2:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven G. Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology and implications for management of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:286–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019884.36724.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visnagri A, Kandhare AD, Shiva Kumar V, Rajmane AR, Mohammad A, Ghosh P, et al. Elucidation of ameliorative effect of Co-enzyme Q10 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathic perturbation by modulation of electrophysiological, biochemical and behavioral markers. Biomed Aging Pathol. 2012;2:157–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Bonadonna RC, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease in the metabolic syndrome prospective data from the Bruneck Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1251–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation among adults in the US. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2745–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsén B, Lahti K, Nissén M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:2709–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick HE, Jones K, Ruotolo G, Jain AK, Henderson J, Lu W, et al. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic American Indians the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:861–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and prediction of cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2004;110:380–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136581.59584.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visnagri A, Kandhare AD, Chakravarty S, Ghosh P, Bodhankar SL. Hesperidin, a flavanoglycone attenuates experimental diabetic neuropathy via modulation of cellular and biochemical marker to improve nerve functions. Pharm Biol. 2014 doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.870584. DOI: 10.3109/13880209.2013.870584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visnagri A, Kandhare AD, Ghosh P, Bodhankar SL. Endothelin receptor blocker bosentan inhibits hypertensive cardiac fibrosis in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Cardiovasc Endocrinol. 2013;2:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stern MP, Williams K, González-Villalpando C, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. Does the metabolic syndrome improve identification of individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2676–81. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Golden SH, Schmidt MI, East HE, et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:385–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberti KG, Zimmet P. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberti K, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome: A new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cederholm J, Eeg-Olofsson K, Eliasson B, Zethelius B, Nilsson PM, Gudbjörnsdottir S. Risk Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes A risk equation from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2038–43. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamnan P, Simmons R, Sharp S, Griffin S, Wareham N. Cardiovascular risk assessment scores for people with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2001–14. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1454-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kothari V, Stevens RJ, Adler AI, Stratton IM, Manley SE, Neil HA, et al. UKPDS 60 risk of stroke in type 2 diabetes estimated by the UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. Stroke. 2002;33:1776–81. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020091.07144.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens JW, Ambler G, Vallance P, Betteridge DJ, Humphries SE, Hurel SJ. Cardiovascular risk and diabetes. Are the methods of risk prediction satisfactory? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:521–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000136418.47640.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, So WY, Kong AP, Ma RC, Ko GT, Ho CS, et al. Development and validation of a total coronary heart disease risk score in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, Stratton IM, Holman R. The UKPDS risk engine: A model for the risk of coronary heart disease in Type II diabetes (UKPDS 56) Clin Sci. 2001;101:671–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamble H, Kandhare AD, Bodhankar S, Mohan V, Thakurdesai P. Effect of low molecular weight galactomannans from fenugreek seeds on animal models of diabetes mellitus. Biomed Aging Pathol. 2013;3:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patil MV, Kandhare AD, Ghosh P, Bhise SD. Determination of role of GABA and nitric oxide in anticonvulsant activity of Fragaria vesca L. ethanolic extract in chemically induced epilepsy in laboratory animals. Orient Pharm Exp Med. 2012;12:255–64. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravikiran M, Bhansali A, Ravikumar P, Bhansali S, Dutta P, Thakur J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic syndrome among Asian Indians: A community survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta R, Deedwania PC, Gupta A, Rastogi S, Panwar RB, Kothari K. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an Indian urban population. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan CE, Ma S, Wai D, Chew SK, Tai ES. Can we apply the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel definition of the metabolic syndrome to Asians? Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1182–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmons RK, Coleman RL, Price HC, Holman RR, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ, et al. Performance of the UK prospective diabetes study risk engine and the Framingham risk equations in estimating cardiovascular disease in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:708–13. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra A, Pandey R, Devi JR, Sharma R, Vikram N, Khanna N. High prevalence of diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia in urban slum population in northern India. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1722. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]