Abstract

Esophageal motility abnormalities are among the main factors implicated in the pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The recent introduction in clinical and research practice of novel esophageal testing has markedly improved our understanding of the mechanisms contributing to the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease, allowing a better management of patients with this disorder. In this context, the present article intends to provide an overview of the current literature about esophageal motility dysfunctions in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Esophageal manometry, by recording intraluminal pressure, represents the gold standard to diagnose esophageal motility abnormalities. In particular, using novel techniques, such as high resolution manometry with or without concurrent intraluminal impedance monitoring, transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations, hypotensive LES, ineffective esophageal peristalsis and bolus transit abnormalities have been better defined and strongly implicated in gastroesophageal reflux disease development. Overall, recent findings suggest that esophageal motility abnormalities are increasingly prevalent with increasing severity of reflux disease, from non-erosive reflux disease to erosive reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Characterizing esophageal dysmotility among different subgroups of patients with reflux disease may represent a fundamental approach to properly diagnose these patients and, thus, to set up the best therapeutic management. Currently, surgery represents the only reliable way to restore the esophagogastric junction integrity and to reduce transient LES relaxations that are considered to be the predominant mechanism by which gastric contents can enter the esophagus. On that ground, more in depth future studies assessing the pathogenetic role of dysmotility in patients with reflux disease are warranted.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, High-resolution manometry, Ineffective esophageal motility, Esophagogastric junction, Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations

Core tip: Esophageal motility abnormalities are among the main factors implicated in the pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. In particular, transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations, hypotensive LES, ineffective esophageal peristalsis and bolus transit abnormalities have been strongly implicated in gastroesophageal reflux disease development. Moreover, recent findings suggest that these abnormalities are increasingly prevalent with increasing severity of reflux disease. Currently, surgery represents the only reliable way to restore the esophagogastric junction integrity and to reduce transient LES relaxations. On that ground, more in depth future studies assessing the pathogenetic role of dysmotility in patients with reflux disease are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) develops when the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus leads to troublesome symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation, with or without mucosal damage and/or complications[1]. Population-based studies indicate that GERD is a highly prevalent condition in Western countries[2]. However, these patients are markedly heterogeneous in terms of clinical features, pathophysiological mechanisms and response to acid suppression, including Barrett’s esophagus (BE), erosive esophagitis (ERD) and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)[3-8]. Of note, the pattern of esophageal motility has been shown to differ in the various subclasses of GERD patients[4].

The pathogenesis of GERD is multifactorial, involving transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations (TLESRs) as well as other LES pressure abnormalities (i.e., hypotensive LES)[9]. Moreover, other factors contributing to the pathophysiology of GERD include impairment of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) (i.e., hiatal hernia), ineffective esophageal acid and bolus clearance, delayed gastric emptying and impaired mucosal defensive factors[9,10].

The recent advent of new technologies, such as combined impedance-manometry and high-resolution manometry (HRM), has represented a major advance in defining and characterizing esophageal motility abnormalities in GERD patients[11,12].

The present article intends to appraise and critically discuss the current literature about esophageal motility dysfunctions in patients with GERD.

MOTILITY ABNORMALITIES IN GERD

The anti-reflux barrier, consisting of LES, crural diaphragm (CD), angle of His and normal thorax-abdomen pressure gradient, prevents reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, whereas esophageal peristalsis helps to clear the refluxate and reduce exposure to noxious components of gastric juice. Consequently, impairment of both EGJ, including LES and CD, and/or esophageal clearance may favor GERD[10]. The main motility abnormalities contributing to the occurrence of refluxes in GERD are impairment of the EGJ (i.e., TLESRs, hypotensive LES, anatomic distortion of the EGJ) and ineffective esophageal motility (IEM).

Impairment of the EGJ

In this context, TLESRs are considered to be the predominant mechanism by which gastric contents can enter the esophagus[13]. According to Spechler and Castell criteria, using conventional manometry testing, TLESRs were defined as periods, lasting 10-60 s, of spontaneous (non preceded by a swallow) LES relaxation[14]. In patients with reflux, up to 75% of reflux events occur during TLESRs, but the proportion of reflux episodes that can be attributed to TLESRs decreases inversely with respect to the severity of GERD, probably due to the increasing prevalence of hypotensive LES in patients with severe GERD[15-19]. In addition, TLESRs appear to play a less important role for reflux episodes in patients with hiatal hernia than in patients without hiatal hernia[15]. Hypotensive LES is diagnosed when LES basal pressure is less than 10 mmHg and represents another major determinant for the EGJ incompetence[20]. Of note, the mean resting LES pressure was found to be significantly lower in patients with ERD than in those with NERD[21,22] and patients with BE and ERD, thus a higher severity of GERD usually has the highest frequency of hypotensive LES[16,17]. Anatomic degradation of the EGJ was also observed to play a role in the genesis of reflux events. Pandolfino et al[23] observed that the opening characteristics of the relaxed EGJ during low-pressure distention were different between GERD patients and normal subjects, that is a wider opening in GERD patients than in normal controls. Such a difference could not be explained entirely by presence of an axial hiatus hernia or by alterations in LES pressure. Thus, mechanical degradation of the EGJ other than hiatal hernia distinguishes GERD patients from normal subjects (i.e., competence of the CD, integrity of the phrenoesophageal ligament, alterations in the muscular wall of the LES)[23].

Ineffective esophageal motility

Impaired esophageal clearance can be caused by IEM, such as ineffective peristalsis or failed peristalsis[24,25]. In 2001, using conventional manometry, IEM was defined as distal esophageal hypocontractility in ≥ 30% of wet swallows, characterized either as contraction amplitude < 30 mmHg in the distal esophagus, 3 and 8 cm above the LES, or as peristaltic waves that are not propagated to the distal esophagus, or absent peristalsis[14]. Hypocontractility is considered the most prevalent esophageal motor disorder in GERD[26,27] and this concept has been further supported by different studies showing that esophageal peristaltic dysfunction was increasingly prevalent with more severe GERD presentation[16,19,26,28]. Of note, in a group of patients with respiratory symptoms associated with reflux, IEM was found in 53% of asthmatics, 41% of chronic coughers and 31% of those with laryngitis[29].

Recently, studies carried out in patients with scleroderma, who are characterized by failed or absent peristalsis and low basal LES pressure, observed that these patients are frequently affected by GERD and its complications[30-32], thus substantiating the relevant role of esophageal clearance for the development of GERD.

As reported in the next section, HRM, with or without concurrent intraluminal impedance monitoring, allows a more complete definition of peristalsis that is, at least in part, highlighted in the Chicago Classification[33].

ADVANCES IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF GERD MOTILITY ABNORMALITIES

Esophageal manometry, by recording intraluminal pressure, represents the gold standard to diagnose esophageal motility abnormalities. Until recently, stationary esophageal manometry was performed using an intraluminal catheter with four to eight water-perfused channels connected to external pressure sensors, including a sleeve sensor to measure continuously the maximum LES pressure[34,35].

Although the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders is based on manometric findings, it is worth noting that endoscopy represents an important diagnostic tool to identify specific causes of motility disorders (i.e., diverticulum, mechanical obstruction, eosinophilic esophagitis)[36-38].

High-resolution manometry

HRM is a recently developed technique using multiple (up to thirty-six) closely spaced pressure sensors to measure intraluminal pressure changes of the entire esophagus during swallowing[39]. Indeed, a dynamic representation of pressure variations is recorded from the upper esophageal sphincter to the lower one, providing an esophageal pressure topography study[40]. Of note, a new practical classification of esophageal motor disorders, the Chicago Classification[33], has been developed using several esophageal pressure topography metrics, constructed from HRM data, able to thoroughly characterise tests swallows[41,42]. Moreover, HRM-based studies improved both EGJ and TLESRs assessment and underlined their role as main mechanisms involved in the development of reflux events[43,44].

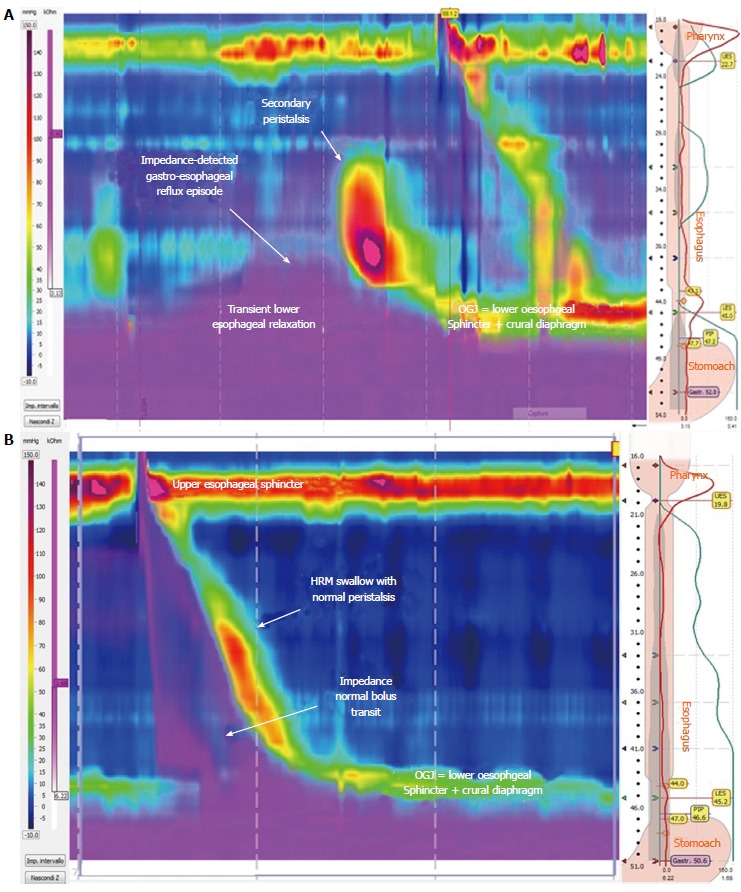

As already known, GERD is primarily a motility disorder in which TLESRs plays a crucial role[45] and, in this regard, recent evidence has highlighted that HRM is reproducible and more sensitive than stationary manometry to detect TLESRs associated with refluxes (Figure 1A), also providing a better interobserver agreement[46-47]. HRM data from patients with esophageal symptoms (dysphagia, chest pain and heartburn/regurgitation), compared to asymptomatic volunteers, revealed that measuring the duration of the esophageal low pressure zone, in the area of transition from striated to smooth muscle, as defined by the time delay between the proximal and distal esophageal contraction waves, might be a meaningful variable in GERD and dysphagia[48]. To date, using HRM with esophageal pressure topography, the definition of TLESRs has been further detailed (Table 1)[43,49,50].

Figure 1.

Portion of high-resolution impedance manometry tracing. A: Showing an example of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and impedance-detected gastroesophageal reflux event with secondary peristaltic wave; B: Showing an example of complete bolus transit during a peristaltic swallow.

Table 1.

Manometric criteria for esophageal motility associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease

| TLESRs: periods (lasting more than 10-60 s) of spontaneous LES relaxation characterized by: |

| (i) absence of swallowing for 4 s before to 2 s after the onset of LES relaxation, |

| (ii) relaxation rate of ≥ 1 mmHg/s |

| (iii) time from onset to complete relaxation of ≤ 10 s |

| (iv) nadir pressure of ≤ 2 mmHg |

| LES relaxations associated with a swallow and fulfilling the above mentioned criteria (ii), (iii) and (iv) that lasted more than 10 s are considered as TLESR |

| Esophagogastric junction: |

| Type 1: no separation between the LES and the crural diaphragm |

| Type 2: minimal separation (> 1 and < 2 cm) making for a double-peaked pressure profile that is not yet indicative of hiatal hernia |

| Type 3: more than 2 cm separation between the LES and the crural diaphragm at inspiration so that two high-pressure zones can be clearly identified |

| 3a: respiratory inversion point distal to the LES |

| 3b: respiratory inversion point proximal to the LES |

| Weak peristalsis with large (a) and small peristaltic defects (b): |

| (i) Mean integrated relaxation pressure < 15 mmHg and > 20% swallows with large breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour ( > 5 cm in length) |

| (ii) Mean integrated relaxation pressure < 15 mmHg and > 30% swallows with small breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour (2–5 cm in length) |

LES: Lower esophageal sphincter; TLESRs: Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations.

Regarding the EGJ assessment, HRM provides a dynamic representation of the EGJ high-pressure zone, making it possible to isolate the extrinsic CD contraction from expiratory LES pressure[51]. On this basis, Pandolfino et al[51] reported that reduced inspiratory EGJ pressure augmentation, an indicator of impaired CD function, was a common finding in GERD patients and a better predictor of GERD prevalence than either LES pressure or LES-CD separation (the HRM signature of hiatus hernia). By means of HRM monitoring, it is possible to document the presence of hiatal hernia measuring simultaneously the separation between the intrinsic LES and CD[52]. Bredenoord et al[15] showed that, in patients with a small hiatal hernia, temporal reduction of the hernia occurs frequently. During spatial separation of the diaphragm and LES, reflux events occurred more often than during reduction of the hernia[15]. Overall, the defects of the EGJ can be evaluated in more detail by means of HRM monitoring and, thus, future studies will better clarify the role of EGJ morphology in GERD development and progression (Table 1).

As for the esophageal peristalsis, a recent HRM study aimed at developing a classification of weak peristalsis in esophageal pressure topography, showed that large (> 5 cm) and small (2-5 cm) pressure troughs in the 20 mm Hg isobaric contour of peristalsis, but not failed peristalsis, occurred more frequently in patients with unexplained non-obstructive dysphagia than in control subjects[53].

In addition, it has been demonstrated that HRM predicts bolus movement more accurately than conventional manometry and identifies clinically relevant esophageal dysfunction not detected by other investigations, including conventional manometry[54].

Combined impedance-manometry

The application of combined impedance-manometry technology provides relevant additional data regarding esophageal motility compared to conventional manometry[55], particularly to identify abnormal bolus transport and clearance during swallows, and to investigate the relationships between bolus transit and LES relaxation[12] (Figure 1B).

After instillation of an acid bolus in healthy subjects, in which Sildenafil provoked a graded impairment in esophageal motility without affecting saliva secretion, simultaneous manometry, pH and impedance study showed that, during upright acid reflux, volume clearance was slightly prolonged only with severe IEM (> 80% abnormal peristaltic sequences)[24]. In the supine position, severe IEM significantly prolonged chemical and volume clearance[24]. In keeping with these results, Fornari et al[25] observed that mild IEM did not affect esophageal clearance in GERD patients. Only severe IEM was associated with prolonged clearance and acid exposure, particularly in supine periods[25]. Recently, we demonstrated that an increasing degree of esophageal mucosal damage in GERD patients (ERD and BE) was associated with a progressively more severe deflection of esophageal function, expressed by an increased frequency of IEM and bolus transit abnormalities, the latter ones also occurring in cases of a normal motility pattern[16].

A new study with combined HRM and impedance monitoring reported that the frequency of TLESRs did not differ between patients with NERD and healthy controls. In patients with NERD, TLESRs were associated more often with reflux episodes than in controls and this association increased when only liquid and mixed refluxes were considered[56]. If confirmed in larger series, it might be hypothesized that factors involved in the occurrence of reflux in NERD patients during TLESRs are different from those in healthy subjects and that the volume of refluxate in patients is higher than that in healthy subjects[56].

Finally, the importance of concomitant manometry and impedance monitoring in order to distinguish rumination syndrome from GERD in patients with predominant regurgitation has been highlighted[57].

DIFFERENCES IN MOTILITY ABNORMALITIES AMONG GERD SUBGROUPS

As mentioned above, several studies reported that motor abnormalities are increasingly prevalent with the severity of GERD, from NERD, ERD to BE[19,21-22,26]. On the other hand, there are studies in contrast with these findings, showing no significant difference in terms of hypotensive LES and IEM between NERD and ERD[58-59]. However, it should be pointed out that, to assess any difference in motility dysfunction among GERD subgroups, a careful classification is warranted. In particular, the inclusion of patients with reflux symptoms and negative upper endoscopy as NERD patients is often made without any attempt of distinguishing functional heartburn (as defined by Rome III criteria) from NERD by means of pathophysiological investigations. To date, NERD is identified as a condition in which typical reflux symptoms appear in patients with negative endoscopy and presence of troublesome reflux-associated symptoms (to acid, weakly acidic or non-acid reflux)[5], whereas functional heartburn is a disorder characterized by symptoms of heartburn not related to GERD, as diagnosed by means of 24-h impedance-pH testing, and must be distinguished from NERD[60-64].

In this context, Frazzoni et al[18] showed that the mean LES pressure was significantly lower in ERD and NERD patients than in controls and functional heartburn patients and that the mean distal esophageal wave amplitude was lower in patients with ERD than in patients with NERD, functional heartburn and controls. In addition, the authors found that the prevalence of hiatal hernia was significantly higher in ERD and NERD than in functional heartburn and controls[18]. In line with these results, we reported that GERD patients have a greater prevalence of abnormally low LES pressure, IEM and hiatal hernia compared with patients with functional heartburn and healthy controls. In particular, we observed that IEM gradually increased from controls and functional heartburn to NERD and from ERD to BE patients[16]. By the application of concurrent manometry and impedance study, it has been shown that ERD is characterized by longer esophageal bolus transit and fewer complete bolus transit than NERD and healthy controls. The authors hypothesized that the noted differences in esophageal bolus transit might reflect a continuum of dysfunction secondary to increasing esophageal mucosal damage[65]. On the other hand, a recent HRM study reported a peristaltic dysfunction in 56% of NERD and 76% of ERD patients, with no significant difference between the two groups[66]. Nevertheless, the authors observed that, using HRM, the frequency of esophageal motility abnormalities in GERD was higher than that reported in a previous study performed with conventional manometry[66].

It is also worth noting the possibility that reflux-induced esophageal contractions can be responsible for symptom perception. Indeed, Pehlivanov et al[67], while studying 12 unclassified subjects with heartburn by means of 24-h pH-metry, combined with synchronized pressure recording and high-frequency intraluminal ultrasound imaging of the esophagus, highlighted a close correlation between heartburn episodes, associated with acid reflux or not, and abnormally long durations of longitudinal muscle contractions. Afterwards, in 10 unclassified subjects complaining of chronic heartburn, Bhalla et al[68] observed that an increase in symptom sensitivity, elicited by acid infusion, occurred in concomitance with a perturbation of esophageal contractility, as revealed by a greater increase in contraction amplitude, contraction duration, muscle thickness and incidence of sustained esophageal contractions during the second acid infusion, in comparison with the first one. On the other hand, Thoua et al[69] showed that acid infusions, although inducing greater acid sensitivity in NERD patients compared to ERD patients and controls, did not induce any changes in the amplitude of esophageal contractions in any of the studied patient groups.

Overall, further studies with advanced techniques such as HRM and proper physiological classification of patients with reflux symptoms are needed in order to better assess the prevalence and pathophysiological role of esophageal motility abnormalities in GERD patients.

TREATMENT PERSPECTIVES

Studies using impedance-pH monitoring have demonstrated that 30%-40% of GERD patients have persistent symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy, mostly related to non-acid reflux events[70,71]. In keeping with this assumption and considering that TLESRs represent the main pathogenetic mechanism of all types of reflux events, controlling the occurrence of TLESRs is considered to be a relevant therapeutic goal in GERD management. However, the actual therapeutic options are limited because there is no specific pharmacological intervention that reliably restores LES function. Drugs interfering with TLESRs, called reflux inhibitors, have been developed, including: γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)B-receptor agonists (baclofen, lesogaberan, arbaclofen placarbil) and antagonists to the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (ADX10059). Despite the promising initial results of these compounds[72-74], their clinical use has been compromised by various side effects or small therapeutic gain[75-77].

The use of prokinetic drugs (i.e., metoclopramide, bethanecol, domperidone) is supposed to accelerate gastric emptying, increase LES tone and hasten esophageal clearance. However, the currently available prokinetics are poorly effective in treating GERD-related dysmotility[78,79] and compounded by side effects[80,81].

Considering the lack of specific effective drugs on reflux-related esophageal dysmotility, dietary and lifestyle interventions are strongly suggested. Particularly, weight loss, head of bed elevation and left lateral decubitus position provided an improvement in GERD measures[82]. Reduction in calorie density and a low-fat diet has positive effects respectively on acid exposure after a meal and on the frequency of reflux symptoms[83]. In addition, chewing gum for half an hour after meals could reduce acidic postprandial esophageal reflux, likely stimulating salivation and swallowing, and thus improving both volume and chemical clearance[84].

Currently, surgery represents the only reliable way to treat esophageal motility abnormalities. Indeed, fundoplication is able to reduce both the volume of proximal stomach and the rate of TLESRs[85-88]. Particularly, the percentage of TLESRs associated with reflux was found to be decreased after fundoplication[85,89]. In addition, surgery is able to restore the eventual EGJ disruption acting on a hiatal hernia, CD defects and gastroesophageal high pressure zone[89]. Pandolfino et al[90] showed that anti-reflux surgery decreases the distensibility of the EGJ to a level similar to normal subjects. Recently, the LOTUS trial, a 5-year randomized, open, parallel-group trial, showed that the remission rate did not differ between optimized esomeprazole therapy (92%) and standardized laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery (85%) in GERD patients (Log-Rank P = 0.048)[91]. However, at 5 years, acid regurgitation was more prevalent in the esomeprazole group than in the anti-reflux surgery group; whereas dysphagia, bloating and flatulence were more prevalent in the anti-reflux surgery group[91]. Moreover, both treatments were well tolerated, with similar safety profiles[91]. Overall, the positive effects of anti-reflux surgery have been clearly demonstrated, not only on reflux symptoms[91-93] but also on dysphagia[94-96]. However, in this context, performing manometry to exclude severe motility abnormalities during the preoperative assessment of patients being considered for anti-reflux surgery is warranted[35]. As to the best surgical procedure to adopt, a systematic review and meta-analyses comparing the effects of laparoscopic Nissen (360°) and Toupet (270°) fundoplication for GERD have assessed that both procedures are equally effective with respect to the percentage of patients with recurrent pathological acid exposure (RR = 1.26, P = 0.29) and subjective reflux recurrence (RR = 1.11, P = 0.61)[92]. In contrast, the Nissen procedure was associated with higher prevalence of postoperative dysphagia (13.5% vs 8.6%, P = 0.02)[92]. On the other hand, another meta-analysis reported that the Toupet procedure was more likely to result in surgery-related complications during the early post-operative period (P = 0.04)[97].

In the last decade, a variety of endoscopic techniques (i.e., radiofrequency ablation, suturing devices) have been proposed as less invasive and costly alternatives to laparoscopic surgery, even although many methods are no longer available primarily because of unacceptable side effects, modest or lack of long-term efficacy, cost, time invested and lack of reversibility[98-100]. To our best knowledge, currently available anti-reflux endoscopic devices include the Stretta procedure (Mederi Therapeutics, Inc, Greenwich, CT), the EsophyX transoral incisionless fundoplication (EndoGastro Solutions, Redmond, WA) and the Endoscopic Plicator (former distributor NDO Surgical, Inc., Mansfield, MA, United States; current product of Ethicon Endosurgery, Sommerville, NJ, United States). The Stretta procedure is an example of a thermal ablation technique for reflux control that has been supposed to be effective in decreasing esophageal acid sensitivity without significant effect on esophageal acid exposure[101-103]. However, a recent review article showed that, in selected GERD patients, Stretta reduces esophageal acid exposure, decreases the frequency of TLESRs, increases patient satisfaction, decreases medication use and improves quality of life[104]. In GERD patients with a small or no hiatal hernia, transoral incisionless fundoplication has been shown to reduce the number of post-prandial TLESRs, the number of TLESRs associated with reflux and EGJ distensibility. This resulted in a reduction of the number and proximal extent of reflux episodes and improvement of acid exposure in the upright position after 6 mo[105]. In addition, previous studies have shown that this procedure permits an increase in LES length and resting pressure and is able to normalize esophageal acid exposure in GERD patients, improving reflux symptoms and quality of life, and reducing PPI use[106]. Endoscopic treatment by full-thickness plication using the Endoscopic Plicator has been shown to significantly reduce GERD symptoms, PPI use and distal esophageal acid exposure in both prospective open-label and randomized controlled trials[107,108]. Recently, a novel Plicator device able to place multiple sutures has been applied, showing that this technique is safe and effective in reducing GERD symptoms, medication use and esophageal acid exposure at 12 mo follow-up without clinical significant side-effects[109,110]. Overall, considering the feasibility and safety profiles that are similar to those of anti-reflux surgery, endoscopic techniques appear to be procedures of interest for GERD; however, they are not as effective as surgery for returning acid exposure to normal, healing esophagitis and resolution of symptoms[111]. Thus, widespread use of these techniques cannot be recommended yet and further controlled prospective trials are urgently required.

Finally, an alternative surgical method to augment LES function has been assessed with a magnetic ring device that is laparoscopically placed around the external diameter of the distal esophagus, the LINX reflux management system, with encouraging results in eliminating reflux symptoms and normalizing esophageal acid exposure[112]. As with the endoscopic techniques, the LINX device is not able to treat the anatomical abnormality of a large hiatus hernia. In conclusion, further controlled prospective studies with long-term follow-up comparing the LINX device to standard pharmacological and surgical alternatives are needed.

CONCLUSION

The pathogenesis of GERD is multifactorial, including esophageal motility abnormalities of which the most important are TLESRs, hypotensive LES and IEM. High-resolution manometry, with or without concurrent intraluminal impedance monitoring, providing an esophageal pressure topography study of the esophagus, allows a more complete definition of esophageal peristalsis. Moreover, HRM-based studies improved both EGJ and TLESRs assessment as a pathophysiological mechanism for the occurrence of reflux events. Particularly, the combination of esophageal manometry and intraluminal impedance measurement allows assessment of abnormal bolus transport and clearance during swallows and investigation of the relationships between bolus transit and LES relaxation. On that ground, more in depth future studies assessing the pathogenetic role of dysmotility in GERD patients are warranted.

To date, the majority of studies in this field report that these esophageal motility abnormalities are increasingly prevalent with increasing severity of GERD, thus from NERD, to ERD and BE patients. A more comprehensive diagnosis and characterization of reflux patients with esophageal dysmotility is nowadays possible and this additional information may be of help in identifying patients who could potentially benefit more from surgery due to restoration of OGJ integrity or reduction of TLESRs.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Kuhn F, Pace F S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarino E, Tutuian R, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Pohl D, Marabotto E, Parodi A, Sammito G, Gemignani L, Bodini G, et al. Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1053–1061. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fass R. Erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease (NERD): comparison of epidemiologic, physiologic, and therapeutic characteristics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:131–137. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225631.07039.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Savarino V. NERD: an umbrella term including heterogeneous subpopulations. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:371–380. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savarino E, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, Frazzoni M, Sammito G, Bonfanti D, Sconfienza L, Assandri L, Gemignani L, Malesci A, et al. The added value of impedance-pH monitoring to Rome III criteria in distinguishing functional heartburn from non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Frazzoni M, Cuoco DL, Pohl D, Dulbecco P, Marabotto E, Sammito G, Gemignani L, Tutuian R, et al. Characteristics of gastro-esophageal reflux episodes in Barrett’s esophagus, erosive esophagitis and healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1061–e280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, Pohl D, Gemignani L, Malesci A, Savarino V. Impedance-pH reflux patterns can differentiate non-erosive reflux disease from functional heartburn patients. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castell DO, Murray JA, Tutuian R, Orlando RC, Arnold R. Review article: the pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease - oesophageal manifestations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 9:14–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando RC. Overview of the mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2001;111 Suppl 8A:174S–177S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00828-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandolfino JE, Roman S. High-resolution manometry: an atlas of esophageal motility disorders and findings of GERD using esophageal pressure topography. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21:465–475. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savarino E, Tutuian R. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and manometry testing. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittal RK, Holloway RH, Penagini R, Blackshaw LA, Dent J. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:601–610. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49:145–151. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Intermittent spatial separation of diaphragm and lower esophageal sphincter favors acidic and weakly acidic reflux. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:334–340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savarino E, Gemignani L, Pohl D, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Assandri L, Marabotto E, Bonfanti D, Inferrera S, Fazio V, et al. Oesophageal motility and bolus transit abnormalities increase in parallel with the severity of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:476–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zentilin P, Conio M, Mele MR, Mansi C, Pandolfo N, Dulbecco P, Gambaro C, Tessieri L, Iiritano E, Bilardi C, et al. Comparison of the main oesophageal pathophysiological characteristics between short- and long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:893–898. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frazzoni M, De Micheli E, Zentilin P, Savarino V. Pathophysiological characteristics of patients with non-erosive reflux disease differ from those of patients with functional heartburn. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:81–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahrilas PJ, Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ, Kern M, Arndorfer RC, Reece A. Esophageal peristaltic dysfunction in peptic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:897–904. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan S, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ. Determinants of gastroesophageal junction incompetence: hiatal hernia, lower esophageal sphincter, or both? Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:977–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho KY, Kang JY. Reflux esophagitis patients in Singapore have motor and acid exposure abnormalities similar to patients in the Western hemisphere. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1186–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quigley EM. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-spectrum or continuum? QJM. 1997;90:75–78. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandolfino JE, Shi G, Trueworthy B, Kahrilas PJ. Esophagogastric junction opening during relaxation distinguishes nonhernia reflux patients, hernia patients, and normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1018–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simrén M, Silny J, Holloway R, Tack J, Janssens J, Sifrim D. Relevance of ineffective oesophageal motility during oesophageal acid clearance. Gut. 2003;52:784–790. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fornari F, Blondeau K, Durand L, Rey E, Diaz-Rubio M, De Meyer A, Tack J, Sifrim D. Relevance of mild ineffective oesophageal motility (IOM) and potential pharmacological reversibility of severe IOM in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1345–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener U, Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Esophageal dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:260–265. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Anggiansah A, Anggiansah R, Young A, Wong T, Fox M. Effects of age on the gastroesophageal junction, esophageal motility, and reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1392–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JC, Cheung CM, Wong VW, Sung JJ. Distinct clinical characteristics between patients with nonerosive reflux disease and those with reflux esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fouad YM, Katz PO, Hatlebakk JG, Castell DO. Ineffective esophageal motility: the most common motility abnormality in patients with GERD-associated respiratory symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1464–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1127_e.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savarino E, Mei F, Parodi A, Ghio M, Furnari M, Gentile A, Berdini M, Di Sario A, Bendia E, Bonazzi P, et al. Gastrointestinal motility disorder assessment in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1095–1100. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gemignani L, Savarino V, Ghio M, Parodi A, Zentilin P, de Bortoli N, Negrini S, Furnari M, Dulbecco P, Giambruno E, et al. Lactulose breath test to assess oro-cecal transit delay and estimate esophageal dysmotility in scleroderma patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savarino E, Bazzica M, Zentilin P, Pohl D, Parodi A, Cittadini G, Negrini S, Indiveri F, Tutuian R, Savarino V, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux and pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma: a study using pH-impedance monitoring. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:408–413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1359OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahrilas PJ, Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal motility disorders in terms of pressure topography: the Chicago Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:627–635. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815ea291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dent J. A new technique for continuous sphincter pressure measurement. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:207–208. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roman S, Kahrilas PJ. Management of spastic disorders of the esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.di Pietro M, Fitzgerald RC. Research advances in esophageal diseases: bench to bedside. F1000Prime Rep. 2013;5:44. doi: 10.12703/P5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schindler A, Mozzanica F, Alfonsi E, Ginocchio D, Rieder E, Lenglinger J, Schoppmann SF, Scharitzer M, Pokieser P, Kuribayashi S, et al. Upper esophageal sphincter dysfunction: diverticula-globus pharyngeus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1300:250–260. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ. Oesophageal high-resolution manometry: moving from research into clinical practice. Gut. 2008;57:405–423. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.127993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandolfino JE, Sifrim D. Evaluation of esophageal contractile propagation using esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24 Suppl 1:20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJ. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24 Suppl 1:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandolfino JE, Zhang QG, Ghosh SK, Han A, Boniquit C, Kahrilas PJ. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux: mechanistic analysis using concurrent fluoroscopy and high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1725–1733. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux of liquids and gas during transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:888–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessing BF, Conchillo JM, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ, Masclee AA. Review article: the clinical relevance of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:650–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roman S, Zerbib F, Belhocine K, des Varannes SB, Mion F. High resolution manometry to detect transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations: diagnostic accuracy compared with perfused-sleeve manometry, and the definition of new detection criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:384–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohof WO, Boeckxstaens GE, Hirsch DP. High-resolution esophageal pressure topography is superior to conventional sleeve manometry for the detection of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations associated with a reflux event. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:427–32, e173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pohl D, Ribolsi M, Savarino E, Frühauf H, Fried M, Castell DO, Tutuian R. Characteristics of the esophageal low-pressure zone in healthy volunteers and patients with esophageal symptoms: assessment by high-resolution manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2544–2549. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Sleeve sensor versus high-resolution manometry for the detection of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1190–G1194. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00478.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Zhang Q, Jarosz A, Shah N, Kahrilas PJ. Quantifying EGJ morphology and relaxation with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1033–G1040. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00444.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandolfino JE, Kim H, Ghosh SK, Clarke JO, Zhang Q, Kahrilas PJ. High-resolution manometry of the EGJ: an analysis of crural diaphragm function in GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1056–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandolfino JE, El-Serag HB, Zhang Q, Shah N, Ghosh SK, Kahrilas PJ. Obesity: a challenge to esophagogastric junction integrity. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:639–649. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roman S, Lin Z, Kwiatek MA, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Weak peristalsis in esophageal pressure topography: classification and association with Dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:349–356. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fox M, Hebbard G, Janiak P, Brasseur JG, Ghosh S, Thumshirn M, Fried M, Schwizer W. High-resolution manometry predicts the success of oesophageal bolus transport and identifies clinically important abnormalities not detected by conventional manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:533–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tutuian R, Castell DO. Clarification of the esophageal function defect in patients with manometric ineffective esophageal motility: studies using combined impedance-manometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:230–236. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ribolsi M, Holloway RH, Emerenziani S, Balestrieri P, Cicala M. Impedance-high resolution manometry analysis of patients with nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tucker E, Knowles K, Wright J, Fox MR. Rumination variations: aetiology and classification of abnormal behavioural responses to digestive symptoms based on high-resolution manometry studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:263–274. doi: 10.1111/apt.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lemme EM, Abrahão-Junior LJ, Manhães Y, Shechter R, Carvalho BB, Alvariz A. Ineffective esophageal motility in gastroesophageal erosive reflux disease and in nonerosive reflux disease: are they different? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:224–227. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152782.22266.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martínek J, Benes M, Hucl T, Drastich P, Stirand P, Spicák J. Non-erosive and erosive gastroesophageal reflux diseases: No difference with regard to reflux pattern and motility abnormalities. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:794–800. doi: 10.1080/00365520801908928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Savarino E, Pohl D, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Sammito G, Sconfienza L, Vigneri S, Camerini G, Tutuian R, Savarino V. Functional heartburn has more in common with functional dyspepsia than with non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2009;58:1185–1191. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.175810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Savarino V, Savarino E, Parodi A, Dulbecco P. Functional heartburn and non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2007;25:172–174. doi: 10.1159/000103879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zerbib F, Bruley des Varannes S, Simon M, Galmiche JP. Functional heartburn: definition and management strategies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Mastracci L, Dulbecco P, Marabotto E, Gemignani L, Bruzzone L, de Bortoli N, Frigo AC, Fiocca R, et al. Microscopic esophagitis distinguishes patients with non-erosive reflux disease from those with functional heartburn. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:473–482. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, Pohl D, Casa DD, Frazzoni M, Cestari R, Savarino V. The role of nonacid reflux in NERD: lessons learned from impedance-pH monitoring in 150 patients off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2685–2693. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen CL, Yi CH, Cook IJ. Differences in oesophageal bolus transit between patients with and without erosive reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daum C, Sweis R, Kaufman E, Fuellemann A, Anggiansah A, Fried M, Fox M. Failure to respond to physiologic challenge characterizes esophageal motility in erosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:517–e200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pehlivanov N, Liu J, Mittal RK. Sustained esophageal contraction: a motor correlate of heartburn symptom. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G743–G751. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhalla V, Liu J, Puckett JL, Mittal RK. Symptom hypersensitivity to acid infusion is associated with hypersensitivity of esophageal contractility. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G65–G71. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00420.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thoua NM, Khoo D, Kalantzis C, Emmanuel AV. Acid-related oesophageal sensitivity, not dysmotility, differentiates subgroups of patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, Castell DO. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–1402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zerbib F, Roman S, Ropert A, des Varannes SB, Pouderoux P, Chaput U, Mion F, Vérin E, Galmiche JP, Sifrim D. Esophageal pH-impedance monitoring and symptom analysis in GERD: a study in patients off and on therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1956–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Q, Lehmann A, Rigda R, Dent J, Holloway RH. Control of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2002;50:19–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boeckxstaens GE, Beaumont H, Hatlebakk JG, Silberg DG, Björck K, Karlsson M, Denison H. A novel reflux inhibitor lesogaberan (AZD3355) as add-on treatment in patients with GORD with persistent reflux symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:1182–1188. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.235630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zerbib F, Bruley des Varannes S, Roman S, Tutuian R, Galmiche JP, Mion F, Tack J, Malfertheiner P, Keywood C. Randomised clinical trial: effects of monotherapy with ADX10059, a mGluR5 inhibitor, on symptoms and reflux events in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vakil NB, Huff FJ, Bian A, Jones DS, Stamler D. Arbaclofen placarbil in GERD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1427–1438. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lidums I, Lehmann A, Checklin H, Dent J, Holloway RH. Control of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. Failure of reflux inhibitors in clinical trials: bad drugs or wrong patients? Gut. 2012;61:1501–1509. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maddern GJ, Kiroff GK, Leppard PI, Jamieson GG. Domperidone, metoclopramide, and placebo. All give symptomatic improvement in gastroesophageal reflux. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grande L, Lacima G, Ros E, García-Valdecasas JC, Fuster J, Visa J, Pera C. Lack of effect of metoclopramide and domperidone on esophageal peristalsis and esophageal acid clearance in reflux esophagitis. A randomized, double-blind study. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:583–588. doi: 10.1007/BF01307583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brogden RN, Carmine AA, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Domperidone. A review of its pharmacological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of chronic dyspepsia and as an antiemetic. Drugs. 1982;24:360–400. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198224050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ganzini L, Casey DE, Hoffman WF, McCall AL. The prevalence of metoclopramide-induced tardive dyskinesia and acute extrapyramidal movement disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1469–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965–971. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fox M, Barr C, Nolan S, Lomer M, Anggiansah A, Wong T. The effects of dietary fat and calorie density on esophageal acid exposure and reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moazzez R, Bartlett D, Anggiansah A. The effect of chewing sugar-free gum on gastro-esophageal reflux. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1062–1065. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ireland AC, Holloway RH, Toouli J, Dent J. Mechanisms underlying the antireflux action of fundoplication. Gut. 1993;34:303–308. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vu MK, Straathof JW, v d Schaar PJ, Arndt JW, Ringers J, Lamers CB, Masclee AA. Motor and sensory function of the proximal stomach in reflux disease and after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1481–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1130_f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnsson F, Holloway RH, Ireland AC, Jamieson GG, Dent J. Effect of fundoplication on transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation and gas reflux. Br J Surg. 1997;84:686–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lindeboom MA, Ringers J, Straathof JW, van Rijn PJ, Neijenhuis P, Masclee AA. Effect of laparoscopic partial fundoplication on reflux mechanisms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bredenoord AJ, Draaisma WA, Weusten BL, Gooszen HG, Smout AJ. Mechanisms of acid, weakly acidic and gas reflux after anti-reflux surgery. Gut. 2008;57:161–166. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.133298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pandolfino JE, Curry J, Shi G, Joehl RJ, Brasseur JG, Kahrilas PJ. Restoration of normal distensive characteristics of the esophagogastric junction after fundoplication. Ann Surg. 2005;242:43–48. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167868.44211.f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Eklund S, Långström G, Lind T, Lundell L. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1969–1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Broeders JA, Mauritz FA, Ahmed Ali U, Draaisma WA, Ruurda JP, Gooszen HG, Smout AJ, Broeders IA, Hazebroek EJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen (posterior total) versus Toupet (posterior partial) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1318–1330. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Antoniou SA, Luketina RR, Emmanuel K, Pointner R. Comparison of results from a randomized trial 1 year after laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2383–2390. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2803-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fibbe C, Layer P, Keller J, Strate U, Emmermann A, Zornig C. Esophageal motility in reflux disease before and after fundoplication: a prospective, randomized, clinical, and manometric study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:5–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herbella FA, Tedesco P, Nipomnick I, Fisichella PM, Patti MG. Effect of partial and total laparoscopic fundoplication on esophageal body motility. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:285–288. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Munitiz V, Ortiz A, Martinez de Haro LF, Molina J, Parrilla P. Ineffective oesophageal motility does not affect the clinical outcome of open Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1010–1014. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tan G, Yang Z, Wang Z. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic total (Nissen) versus posterior (Toupet) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease based on randomized clinical trials. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vassiliou MC, von Renteln D, Rothstein RI. Recent advances in endoscopic antireflux techniques. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:89–101, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Falk GW, Fennerty MB, Rothstein RI. AGA Institute technical review on the use of endoscopic therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1315–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fass R. Alternative therapeutic approaches to chronic proton pump inhibitor treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:338–345; quiz e39-40. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Corley DA, Katz P, Wo JM, Stefan A, Patti M, Rothstein R, Edmundowicz S, Kline M, Mason R, Wolfe MM. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms after radiofrequency energy: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:668–676. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Coron E, Sebille V, Cadiot G, Zerbib F, Ducrotte P, Ducrot F, Pouderoux P, Arts J, Le Rhun M, Piche T, et al. Clinical trial: Radiofrequency energy delivery in proton pump inhibitor-dependent gastro-oesophageal reflux disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1147–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arts J, Sifrim D, Rutgeerts P, Lerut A, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of radiofrequency energy delivery at the gastroesophageal junction (the Stretta procedure) on symptoms, acid exposure, and esophageal sensitivity to acid perfusion in gastroesophagal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2170–2177. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9695-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Franciosa M, Triadafilopoulos G, Mashimo H. Stretta Radiofrequency Treatment for GERD: A Safe and Effective Modality. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:783815. doi: 10.1155/2013/783815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rinsma NF, Smeets FG, Bruls DW, Kessing BF, Bouvy ND, Masclee AA, Conchillo JM. Effect of transoral incisionless fundoplication on reflux mechanisms. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Testoni PA, Vailati C. Transoral incisionless fundoplication with EsophyX® for treatment of gastro-oesphageal reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rothstein R, Filipi C, Caca K, Pruitt R, Mergener K, Torquati A, Haber G, Chen Y, Chang K, Wong D, et al. Endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A randomized, sham-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:704–712. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pleskow D, Rothstein R, Kozarek R, Haber G, Gostout C, Lembo A. Endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of GERD: long-term multicenter results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.von Renteln D, Schiefke I, Fuchs KH, Raczynski S, Philipper M, Breithaupt W, Caca K, Neuhaus H. Endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease using multiple Plicator implants: 12-month multicenter study results. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1866–1875. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Antoniou SA, Spaun G, Pointner R, Swanstrom LL. Subjective and objective data on esophageal manometry and impedance pH monitoring 1 year after endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of GERD by using multiple plication implants. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino JE, Smout AJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2013;381:1933–1942. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bonavina L, DeMeester T, Fockens P, Dunn D, Saino G, Bona D, Lipham J, Bemelman W, Ganz RA. Laparoscopic sphincter augmentation device eliminates reflux symptoms and normalizes esophageal acid exposure: one- and 2-year results of a feasibility trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:857–862. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd879b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]