Abstract

The discrepancy between organ need and organ availability represents one of the major limitations in the field of transplantation. One possible solution to this problem is xenotransplantation. Research in this field has identified several obstacles that have so far prevented the successful development of clinical xenotransplantation protocols. The main immunologic barriers include strong T cell and B cell responses to solid organ and cellular xenografts. Additionally, components of the innate immune system can mediate xenograft rejection. Here, we review these immunologic and physiologic barriers and describe some of the strategies that we and others have developed to overcome them. We also describe the development of two strategies to induce tolerance across the xenogeneic barrier, namely thymus transplantation and mixed chimerism, from their inception in rodent models through their current progress in pre-clinical large animal models. We believe that the addition of further beneficial transgenes to Gal knockout swine, combined with new therapies such as Treg administration, will allow for successful clinical application of xenotransplantation.

Keywords: xenotransplantation, tolerance, thymus transplant, mixed chimerism, genetically modified swine, NK cells

Introduction

One of the major problems confronting the field of transplantation today is that the demand for organ transplants currently outstrips the number of suitable donor organs. Efforts such as indicating organ donor status on Facebook have produced only modest increases in organ donation in recent years (1), and there has been a relative plateau of organ donor availability nationwide (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network database). One potential solution to this issue is utilization of organs from a different species, or xenotransplantation. In the early 20th century, the first attempts at transplants to humans utilized animal organs due to ethical concerns related to the use of organs from other humans (2). With increased understanding of immunology and histocompatibility, the enthusiasm for xenotransplantation has waxed and waned over the past century. Great progress has been made in understanding and overcoming the barriers to xenograft function and survival, but several hurdles remain. Nevertheless, we believe that xenotransplantation remains the most promising approach for addressing the organ shortage. This review will define some of the immunological barriers that remain and describe the development of our strategies to overcome them by inducing immunological tolerance.

Source Animal

Xenotransplantation from species closely related to humans presents fewer immunological barriers than transplantation from vastly disparate species. This led several early investigators to perform clinical transplants from nonhuman primates (primarily chimpanzees and baboons) to humans. The most successful of these, a renal transplant from chimpanzee, functioned for 9 months before the recipient died of pneumonia (3). In the early 1990’s, the Pittsburgh group transplanted baboon livers to humans with viral hepatitis. The longest survivor of this series was 70 days (4). However, due to growing concerns of viral transmission from closely related species, the US Department of Health and Human Services developed new guidelines in 1999 that effectively declared a moratorium on primate-to-human transplantation (5). Thereafter, focus turned to using swine as the source animal. This species was targeted as the most suitable animal due to the relatively similar size of organs to their human counterpart, physiologic similarity (swine insulin had been used for decades in diabetic patients), favorable breeding characteristics (large litters and rapid maturation), and feasibility for genetic manipulation to add favorable genes or to delete unfavorable ones (6, 7). Despite the identification of a theoretically transmittable endogenous retrovirus in pigs, recent data have shown that the risk of disease transmission is low (8–10) and can be further minimized by producing porcine endogenous retrovirus “non-transmitting” pigs by breeding or genetic modification (11–13). Nevertheless, clinical protocols will require adherence to strictly regulated risk reduction measures, including the use of source pigs generated in closed colonies to exclude potential pathogens and a surveillance program to monitor for infectious disease transmission (14, 15). Additionally, use of swine as source animals added a major immunologic hurdle to successful xenotransplantation due to high levels of preformed anti-swine antibodies.

Initial attempts at preclinical swine-to-primate transplantation were hampered by the presence of antibodies to α-galactose-1,3-galactose (Gal), a sugar displayed on the surface of pig cells, but not in humans or Old World monkeys due to a frame shift mutation in α-1,3-galactosyltransferase (GalT) (16). Sensitization to this sugar is thought to arise from exposure to Gal+ bacteria in the normal intestinal flora. Anti-Gal antibodies have been estimated to constitute as much as 1–4% of circulating immunoglobulin (Ig) in human sera (17, 18). This robust antibody response to Gal leads to hyperacute rejection of Gal positive swine transplants in Old World monkeys. The development of GalT knockout (GalTKO) animals in 2002 eliminated this obstacle (19, 20). However, initial series using GalTKO swine as source animals demonstrated that important additional xenogeneic immune responses must be overcome before clinical xenotransplantation can be considered. Here, we provide a brief overview of the main obstacles and the strategies that we and others have developed to overcome them.

T cell responses

1) Direct pathway

Unique to the transplant environment, the direct pathway of antigen presentation refers to recipient T cell recognition of antigen presented by a donor antigen-presenting cell (APC). This pathway requires appropriate interaction between the T cell receptor and an MHC/peptide ligand. The duration of direct pathway stimulation depends on the longevity of donor APC in the recipient environment. Given the potentially extensive differences between HLA and swine leukocyte antigens (SLA) (21), there was some initial uncertainty that the direct pathway would be active in swine-to-human xenotransplantation. Hope that T cell responses across xenogeneic barriers would be weak was encouraged by experiments performed by Moses et. al. that demonstrated a lack of effective interaction between the T cell receptor (TCR) of human CD4 cells and class II molecules on murine APCs. Unfortunately, this defect did not apply to the swine/human combination. Several investigators described activation of human CD8+ and CD4+ T cells by SLA class I and class II respectively (22–24). CD4 direct reactivity appears to be directed toward the SLA-DR molecule (specifically the beta chain) as determined by blocking antibodies and by assessing T cell clone cross-reactivity between known haplotypes (22, 24). Additionally, porcine aortic endothelial cells have been shown to be capable of providing appropriate ligation and costimulation through human CD2 and CD28 (25). The magnitude of the direct pathway response using limiting dilution assay has been determined to be on par with that seen in a fully MHC mismatched allogeneic transplant (24). The importance of the direct pathway in vivo has yet to be determined, but is likely to be considerable. Experiments have shown that porcine endothelial cells do not upregulate class II molecules following stimulation with human IFN-γ (26), but do constitutively express class I, class II and costimulatory molecules (27, 28). These findings led to the recent development of genetically engineered swine that express low levels of class II and induce a decreased T cell response in vitro (29). Another strategy to limit T cell activation is the transgenic up-regulation of inhibitory costimulatory molecules, such as CTLA4-Ig and PD-1 ligands (30–32). Together, these innovations may limit the role of the direct pathway in xenograft rejection.

2) Indirect pathway

The indirect pathway of T cell recognition involves presentation of donor-derived peptides on recipient APCs. Not surprisingly, several investigators have shown this pathway to be active in xenotransplantation (22, 24). Importantly, it appears that the response to porcine antigens is stronger than the indirect response to alloantigens (24). In vivo, detailed analysis of porcine islet xenografts in rhesus macaques showed an increased number of IFN-γ producing T cells activated by the indirect pathway. This was associated with intraislet T cell and macrophage infiltration. The authors also commented that the immunosuppressive regimen prevented allograft rejection in the same species, suggesting that the xenogeneic T cell responses were more vigorous and difficult to control than alloresponses (33). The magnitude of the indirect pathway xenoresponse is also reflected in the rapid and potent development of induced antibody responses in vivo. Primates that received porcine kidneys or hearts using immunosuppressive regimens not designed for extensive T cell control develop rapid acute humoral xenograft rejection and, importantly, anti-swine IgG (34–36), suggesting that CD4 T cells activated through the indirect pathway primed xenoreactive B cells and induced class switching to IgG via cognate interactions.

3) T cell interaction with the innate immune system

Once activated, T cells can mediate direct anti-swine cytotoxic effects through the Fas-Fas ligand pathway (37). They also prime components of the innate immune response by producing cytokines that activate macrophages and natural killer cells (38, 39). These T cell-activated components of the innate immune system have been shown to participate in xenograft rejection, particularly of cellular transplants such as porcine islets. Indeed, T cells have been shown to be essential promoters of islet xenograft rejection by macrophages (38, 40–42), and transplant immunosuppression protocols that utilize costimulatory blockade to control T cell responses have yielded significantly improved xenograft islet survival times in pig-to-primate models (33, 42, 43) and prevented rejection of pig islets in humanized mice(33, 42, 43). Remarkably, T cell depletion prevented islet graft infiltration with human macrophages and B cells in the humanized mouse model (41). In rodent models, T cells are required for xenogeneic islet rejection (44) and interact with macrophages through TCR-MHC interactions (45). T cells recruit and activate macrophages (38), which home to islet xenografts in this rodent model (39).

Macrophages also play a major role in preventing xenogeneic bone marrow engraftment (46, 47). One explanation for their greater importance in xenogeneic compared to allogeneic bone marrow rejection is that macrophages express an inhibitory receptor, signal-regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα), which recognizes a ubiquitously expressed cell surface protein CD47 (48). This interaction serves as a “marker of self”, inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis. In pig-to-mouse cellular transplants, the CD47-SIRPα interaction was found to be ineffective (49) and restoration of this interaction via transgenic expression of murine CD47 on porcine cells reduced phagocytosis by mouse macrophages (50). The pig-to-human interaction of this receptor and ligand is likewise ineffective and inducing expression of human CD47 on porcine cells reduces cellular phagocytosis by human macrophages in vitro (49). This interaction may be more important for cellular transplants like islets and bone marrow that are exposed directly to blood components (see section on mixed chimerism below). Restoration of appropriate CD47-SIRPα interactions in the human-to-mouse bone marrow transplant (BMT) model augmented engraftment (51), indicating the importance of this pathway in xenogeneic mixed chimerism studies. Likewise, hepatocytes appear to be subject to macrophage-mediated rejection unless they express the appropriate CD47 (52). However, thymic xenografts are unaffected by the lack of CD47 expression (53), consistent with the interpretation that solid tissues are not susceptible to direct, T cell-independent macrophage-mediated destruction. To address the important species incompatibility for pig CD47 and human SIRPα, we have produced GalTKO miniature swine that are transgenic for human CD47 to serve as the source animal for future swine-to-baboon bone marrow transplant experiments (54, 55). Together, these studies suggest that if T cell tolerance is induced via thymus transplantation or mixed chimerism (see below), macrophage-mediated rejection should be mitigated if hCD47 transgenic bone marrow or other cellular grafts such as islets are utilized.

Antibody responses

1) Antigen targets

Following the development of GalTKO swine, it was discovered that humans and primates possessed significant amounts of anti-swine antibodies recognizing non-Gal antigens. The level of these antibodies was not high enough to cause hyperacute rejection in primate recipients of GalTKO organs, but was sufficient to cause damage to organs or cellular transplants. To date, the target(s) of the non-Gal antibodies remain to be definitively described. In contrast to anti-Gal antibodies, which develop within the first 3 months, non-Gal antibodies are nearly absent for the first year of life (56). Early studies that relied on adsorption of anti-Gal antibodies and Gal+ target cells suggested that anti-HLA antibodies cross-reacted with SLA (57–59). A more sophisticated analysis using monoclonal Ab reactive to HLA antigens showed some cross reactivity with SLA, but most of these antibodies were IgM and polyreactive with multiple HLA (60). Two studies went on to show no correlation between PRA and reactivity to GalTKO PBMC (61, 62). Together, these data suggest that highly allosensitized patients will in general be candidates to receive a GalTKO porcine organ (63). The Mayo Clinic group performed an analysis of non-Gal antibodies in baboon recipients of Gal positive and GalTKO hearts. They found that non-Gal antibodies bound to a number of stress response-related endothelial cell antigens, but failed to identify an immunodominant antigen that could be the focus of future targeted genetic deletion (64). A subsequent analysis also identified porcine CD9, CD46 and CD59 as targets of non-Gal antibodies. Since some of these antigens are regulators of the complement response, their neutralization by antibody binding would have the additional effect of making the cell more susceptible to complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). They also found a putative carbohydrate target of non-Gal antibodies due to antibody binding to the product of a gene with homology to human β-1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase 2 (65). Another possible antibody target, N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NeuGc), may be important (66). Similar to the situation for Gal, humans lack a functional gene for CMP-NeuAc hydroxylase that is required for NeuGc synthesis (67). Nonhuman primates have a functional CMP-NeuAc hydroxylase gene (68) and therefore current translational models cannot determine the importance of this antigen (69). However, anti-NeuGc antibodies are present in the majority of human sera and might be relevant for clinical pig-to-human transplants (70). Recently, CMPH knockout pigs have been generated on the GalTKO background (71). Nonetheless, it seems unlikely that antibody-mediated rejection will be completely prevented by targeted deletion of a specific xenogeneic antigen and efforts towards controlling antibody responses must be focused on broadly eliminating their production (72).

2) Cells producing non-Gal antibody

Much of the work describing the phenotype of natural antibody-producing cells involved the identification of anti-Gal producing cells due to their binding with their well-defined antigenic target. Using GalTKO mice, we showed that anti-Gal IgM production was mediated by B-1b-like CD5−, CD11b− splenic B cells. Additionally, a population of B cells in the peritoneal cavity that expresses anti-Gal receptors, but that does not secrete anti-Gal antibody, is phenotypically CD5−, CD11b+ (73)These peritoneal B-1b cells are precursors of the CD5−, CD11b− anti-Gal IgM secreting splenic B cells (74). Similar to the results in GalTKO mice, the spleen was found to be the major source of anti-Gal IgM-secreting cells in nonhuman primates (NHP) and humans. (75). Following sensitization with Gal+ porcine tissues in NHP, IgG-secreting cells were detected in the spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow at 2 months. Six months after sensitization, the majority of the anti-Gal IgM and IgG-producing cells were localized to the bone marrow. Phenotypically, most IgM-secreting cells were CD20+, CD138− and surface Ig+, although a small percentage of plasma cells in the spleen and bone marrow were found to secrete anti-Gal IgM. Most anti-Gal IgG-producing cells were CD138+ plasma cells. A study performed by Fischer-Lougheed et. al. in rhesus macaques demonstrated that anti-Gal secreting cells were CD5−, CD11b+, similar to the B-1b cells in GalTKO mice (76). Unfortunately the same approach, which relies on using the anti-Gal IgM receptor on antibody-secreting cells to define xenoantibody-producing cells, has little applicability in the current era, when the relevant xenoantibodies under study are directed to poorly-defined non-Gal antigens. Extrapolation of this approach to non-Gal-producing cells may be possible for defined carbohydrate xenoantigens. However, given that many of the described non-Gal antibodies are directed to protein antigens (or possibly carbohydrate or lipid moieties on protein antigens, see above), cells that express a different phenotype from anti-Gal antibody-producing cells may be important. Therefore, further work to define the phenotype(s) of non-Gal natural antibody-producing cells is required.

Despite the lack of an accurate phenotypic description of non-Gal antibody-secreting cells, attempts to eliminate or reduce the anti-swine antibody response using B cell-depleting antibodies have been attempted. Two studies examined the effect of B cell depletion on anti-Gal antibody production in baboons by using anti-CD20 mAb (77, 78). While B cells were effectively depleted, neither group found a sustained decrease in anti-Gal antibody levels, even when antibody depletion was combined with whole body irradiation. However, a study from the Maryland group demonstrated that intense B cell depletion prolonged survival of GalTKO/hCD46 transgenic hearts (79). The difference in these results could be explained by the possibility that non-Gal xenoantibody-producing cells express CD20, whereas the majority of anti-Gal antibody-secreting cells are CD20−/low. The results may also reflect a major role for B cells in presenting antigen to T cells that promote non-Gal antibody production. Attempts at targeted plasma cell depletion with anti-CD38 or bortezomib were ineffective in reducing anti-Gal antibody levels (78, 80). Additionally, the effects of antibodies such as belimumab that target B cell survival factors on the production of non-Gal antibodies have not been reported. Further study is needed to clarify the effect, if any, of new pharmacological agents on non-Gal antibodies.

Other immunological barriers

NK cells

Like macrophages, NK cells are components of the innate immune system that have importance for xenotransplantation. Human NK cells have multiple receptors with inhibitory activity including CD85, CD158 and CD159, as well as a number of activating receptors of different molecular classes. These inhibitory receptors recognize class I HLA molecules that are constitutively expressed on host cells. Insufficient inhibitory interactions to balance interactions with activating ligands can result in destruction of a xenogeneic cell (81, 82). Early experiments determined that inhibitory interactions of NK cells were defective in multiple xenotransplantation models. In vitro, human NK cell-mediated elimination of porcine cells is mitigated by expressing human HLA-Cw3, HLA-Cw4 or HLA-E on the target pig cells (83–85). This NK killing was stimulated by IL-2 in vitro (86), suggesting that it could be augmented by T cell priming. In vivo, NK cells are prominent in rejecting solid organ xenografts in rodent models (87) (81) and are also present, albeit in lower numbers, in GalTKO pig-to-primate hearts and kidneys (88, 89). A second method by which NK cells act in vivo is by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) (90), which is induced by binding of NK cell FcγRIII (CD16) to the Fc portion of xenoreactive antibodies (91). The importance of the two pathways in vivo has been difficult to parse out in xenotransplant models. Nevertheless, it is clear that NK cells represent a significant barrier in xenogeneic bone marrow transplantation, with a greater inhibiting effect on engraftment of xenogeneic than allogeneic bone marrow (92). In at least one species combination, however, NK cells did not reject xenogeneic donor cells once chimerism had been established and continued NK depletion did not alter the kinetics of gradual xenochimerism loss in rat→mouse mixed chimeras (93). Consistently, mouse NK cells exhibited “tolerance” to rat donor cells in these mixed chimeras (94, 95) (see below). Islet transplant models have shown that NK cells are not required for rejection and likely play a minor role overall (96, 97). Thus, the major obstacle NK cells seem to present is the impairment of bone marrow engraftment.

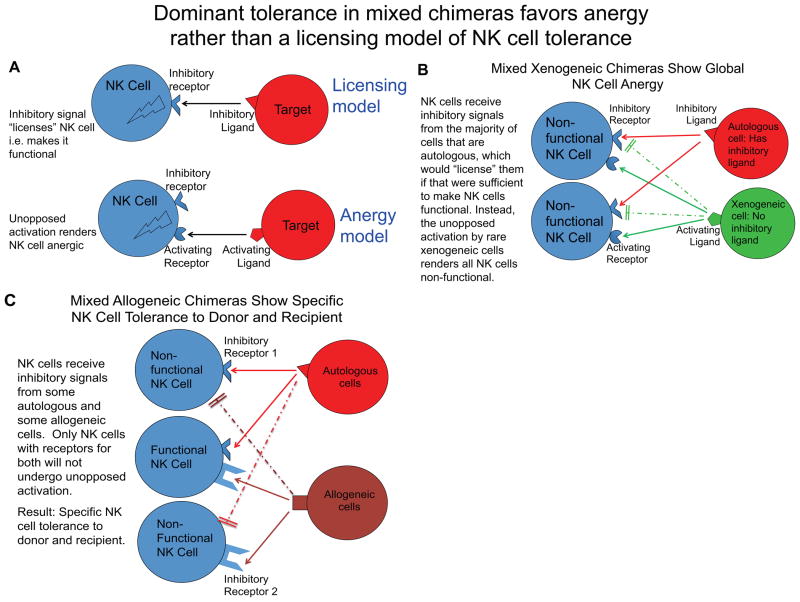

Several strategies may be able to minimize the contribution of NK cells to xenograft rejection. First, the addition of class I HLA to the cell surface of the source animal would provide an inhibitory ligand to human NK cells and thereby decrease their ability to kill. For this reason, transgenic human HLA-E-expressing swine were generated and studies indicate that their cells are indeed resistant to human NK-mediated cytotoxicity compared to wild-type swine cells (98). In murine mixed allogeneic chimeras, we have shown that NK cells become specifically tolerant to the donor cells, with preservation of the ability to reject class I-deficient cells (99). However, in the rat-to-mouse mixed chimerism model, NK cell tolerance was associated with global unresponsiveness of the murine NK cells (95). In our view, the most plausible explanation for these divergent results is that the presence of a cell population lacking any inhibitory ligand for recipient NK cells results in chronic activation of all NK cells and hence global anergy (Figure 1). Such “disarming” of NK cells has been used to explain dominant hyporesponsiveness in mixed chimeras involving class I-deficient donors or mosaic class I MHC transgenic mice (100, 101). In general, inhibitory receptors have been shown not to function between species, whereas activating receptors have been found effective (84, 98, 102–112). In the case of mixed xenogeneic chimeras, therefore, the xenogeneic cells are completely lacking in ligands that inhibit recipient NK cells, so all NK cells are chronically activated and become anergic (Figure 1B). In contrast, allogeneic cells in mixed allogeneic chimeras express MHC molecules that will inhibit some subsets of recipient NK cells expressing relevant inhibitory receptors. Thus, in mixed allogeneic chimeras, only the subset of recipient NK cells lacking an inhibitory ligand for donor cells will chronically receive unopposed stimulation and hence become anergic; the consequence is a functional NK cell repertoire that is inhibited by recognition of the donor (in addition to recipient) cells (Figure 1C). This explanation for the divergent results in mixed allogeneic vs. xenogeneic chimeras is consistent with the “disarming” concept (101), as opposed to the “licensing” model of NK cell tolerance (113), which instead proposes that inhibitory interactions license NK cells to become functional. Consistent with the disarming model, NK cells have been shown to tune their responsiveness in direct proportion to the number of inhibitory interactions they experience in vivo (114). Moreover, continuous engagement of an NK cell activating receptor renders NK cells hyporesponsive (115, 116). The complete lack of inhibitory interactions with xenogeneic cells could thereby render all NK cells anergic. Based on these results, and the lack of effect of chronic NK cell depletion on gradual loss of rat chimerism in murine mixed chimeras, it seems unlikely that NK cells would participate in loss of chimerism once it is established, but the lack of NK cell function in chimeras may make them susceptible to viral and oncologic complications (95). Moreover, studies are needed to determine whether or not mixed porcine chimerism in primates or humanized mice would result in a similar state of NK cell tolerance associated with global unresponsiveness.

Figure 1.

Model for NK cell responses in mixed allogeneic and xenogeneic chimeras. Licensing model requires an inhibitory ligand-receptor interaction to activate an NK cell, whereas the anergy or disarming model predicts that persistent unopposed activation renders an NK cell anergic (A). In mixed xenogeneic chimeras, donor cells present activating ligands, but not inhibitory ligands, leading to unopposed NK cell activation and global unresponsiveness, consistent with the disarming model of NK cell tolerance (B). In mixed allogeneic chimeras, autologous and allogeneic cells both display inhibitory ligands, resulting in NK cell function with specific tolerance to donor and recipient (C). Dashed line indicates lack of inhibitory receptor-ligand interaction.

Complement/Coagulation

The complement system consists of a group of blood-borne proteins that participate in innate and adaptive immune responses. It is activated by three different pathways, the classical (triggered by antibodies), alternative, and lectin pathways (117, 118). Once activated, it proceeds toward the assembly of the membrane attack complex and cell lysis. Several cell surface proteins have been identified that serve as inhibitors of different stages of complement activation (119). These complement regulatory proteins (CRP) have limited effects on xenogeneic complement activation and thus xenogeneic cells are more susceptible to complement-mediated damage. Since complement is an effector of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, CRPs were an early focus for genetic modulation of source animals. To date, animals that express human CD46, CD55, CD59 (120–123) or multiple CRPs have been produced (124, 125). Cells from these animals have decreased susceptibility to complement-mediated damage and their organs are less susceptible to hyperacute rejection (126–128). Animals that express human CRPs may be especially critical for xenotransplantation if antibody responses cannot be completely eliminated, as CRPs may have a role in graft accommodation (129, 130). An additional effect of the complement cascade is the activation of the coagulation pathway. This is particularly deleterious in xenotransplantation since the inhibitors of the clotting pathway expressed on the donor endothelium do not interact appropriately with the host hematologic system (131). This coagulation dysregulation is an identified hurdle to successful solid organ xenotransplantation, with thrombotic microangiopathy having been reported in pig-to-baboon renal and cardiac transplants (88, 132–134). One pathway that has been extensively investigated by the Robson group is the interaction of CD39 with the coagulation system (135–137) and work in this field was the subject of a recent review (138). Data indicate that genetic modification of the source animal via expression of human CD39 or other regulators of the coagulation cascade may alleviate the development of thrombotic microangiopathy (124, 139). Recently, several new transgenic pigs expressing human thrombomodulin and human endothelial protein C receptor have been constructed and prolonged heart graft survival has been achieved using the human TM transgenic, CD46 transgenic GalTKO pigs (140). We also believe that control of the antibody response will in turn limit activation of complement and thereby the coagulation cascade and consequently help to prevent the development of thrombotic microangiopathy.

Tolerance Induction

Given the robust responses of T and B cells to xenografts, and their priming of other components of the immune system through cytokine production and antibody-Fc receptor interactions, it is probable that the level of systemic immunosuppression required to prevent rejection will be high and lead to unacceptable side effects in recipients. Therefore, we believe that the induction of immunological tolerance to xenotransplants will likely be required for clinical application of this modality. One advantage of xenotransplantation compared to allotransplantation is that every transplant procedure can be planned. This allows for the application of scheduled conditioning regimens in the recipient preoperatively, for quality control of the source animals and also for any required manipulation of the source animal. In this respect, although the immunological barriers may be greater, the development of tolerance-inducing regimens that are administered over a period of time may be more readily applied to xenotransplantation than, for example, to deceased donor allotransplantation. For the past twenty-five years, we and our colleagues have worked on two basic strategies of tolerance induction. The first strategy we describe involves the transplantation of donor thymus tissue to induce T cell tolerance. Since negative selection of maturing T cells occurs in the thymus, depletion of peripheral T cells followed by xenogeneic thymus transplantation reprograms the T cell compartment to regard porcine antigens displayed in the donor thymus as self (141, 142). The second strategy we have investigated is the use of mixed chimerism to induce both T cell and B cell tolerance.

1) Thymus Transplant

A) Rodent Models

The first proof of principle experiments demonstrating that xenogeneic thymus transplants could induce tolerance were performed in the pig-to-mouse model (143, 144). The general protocol involved host thymectomy and exhaustive recipient T cell depletion, followed by implantation of fetal or neonatal porcine thymus tissue underneath the renal capsule. Host CD4+ peripheral T cell numbers recovered by 8 weeks post-grafting in animals that received porcine thymus tissue, whereas controls without thymus tissue maintained low CD4 counts. Further analysis of the CD4 T cell phenotype revealed that these cells were CD44low CD45RBhigh CD62Lhigh, indicating they were naïve cells that had developed in the porcine thymus, which contained similar numbers of phenotypically normal thymocytes as were present in normal mouse thyme, and were not progeny of homeostatic expansion of CD4 T cells that had escaped depletion (145). Using MHC class II knockout and various TCR transgenic mice, positive selection of maturing CD4 cells was shown to be mediated by swine MHC with no contribution from murine APCs that populate the swine xenograft (146). In contrast, both porcine and murine MHC contributed to negative selection, resulting in a T cell repertoire that was specifically tolerant of the donor pig and of the recipient mouse (147). Using MLR assays, it was shown that these mice were unresponsive to donor antigens, but remained responsive to allogeneic or third-party swine xenoantigens (148). In vivo, murine recipients of swine thymus were tolerant to porcine skin grafts with the same SLA type, but not 3rd party allogeneic (144) or 3rd party pig skin (148). The contribution of host class II MHC to negative selection of thymocytes (144, 147) has significant implications for the avoidance of graft-versus-host disease in thymus transplant recipients. However, we found that a minority (~10%) of fetal porcine thymus and liver grafted thymectomized and T cell depleted B6 mice developed a wasting syndrome of autoimmune origin. When nude mice were used as recipients, the percentage of mice developing this syndrome increased to 60% (149). Since incomplete deletion of Tregs with anti-CD4 in B6 mice could explain the decreased incidence of autoimmunity in B6 compared to nude mice that would not have preexisting any thymus-derived Tregs, we investigated the role of Tregs in suppressing host-reactive T cells. The autoimmune syndrome could be transferred by CD4 T cells from pig thymus-rafted nude mice to syngeneic nude mice, but was mitigated by the co-transfer of normal syngeneic splenocytes to secondary nude mouse recipients (149). While this effect could be attributed in part to suppression of homeostatic expansion of host-reactive T cells, the autoimmune syndrome was most potently suppressed by CD4+CD25+ normal splenocytes, suggesting that Tregs helped suppress autoimmunity (149). We also found that normal numbers of mouse Tregs were generated in the porcine thymus grafts, but they ineffectively suppressed effector cells in vitro and in vivo. However, injecting recipient-type murine thymic epithelial cells (TECs) into the porcine thymus at the time of grafting enhanced Treg function in this model and reduced autoimmunity in vivo (150). The capacity of non-Tregs from the pig thymus-grafted mice to transfer disease was also diminished by the implantation of mouse TECs in the grafts (149), consistent with the important role of TECs in expressing tissue-specific antigens and thereby contributing to negative selection of thymocytes with such specificities (151). These results suggest that inclusion of recipient TECs in xenogeneic thymus grafts may promote positive selection of recipient-specific Tregs and negative selection of tissue antigen-specific effector T cells. Since we have also shown that T cells generated in xenogeneic thymus grafts by positive selection on porcine MHC appear to have a defect in post-thymic maturation, proliferation and/or survival (possibly due to lack of donor MHC in the periphery) (150), positive selection of Tregs by host MHC, and subsequent restimulation by host MHC in the periphery, may be needed to prevent autoimmunity and enhance generation/function of Tregs.

Although the pig-to-mouse model demonstrated that xenogeneic thymus transplants could support cross-species T cell development, mediate positive and negative selection of maturing thymocytes and promote donor-specific tolerance, it remained to be shown that the pig-to-human combination would yield similar results. To accomplish this, we implanted fetal porcine thymus and human fetal liver under the renal capsule of SCID mice (152). These animals reconstituted peripheral T cells by 10 weeks and the thymocytes in the porcine thymus grafts had similar phenotypic profiles as those that developed in fetal human thymus grafts. Using spectratyping, we demonstrated that the human T cell repertoire generated in the porcine thymus was diverse and similar to that generated in human thymus grafts (153). In MLR assays, these T cells were tolerant to donor swine antigens, but not to 3rd party swine or allogeneic antigens. To determine the mechanism of tolerance, IL-2 was added to MLR assays and the donor-specific tolerance persisted, suggesting a deletional mechanism of tolerance. Subsequently, we improved the level of immune reconstitution by using NOD/SCID mice as recipients and giving human CD34 cells i.v. In these studies, we have been able to demonstrate that peripheral human T cells are also specifically tolerant to the donor pig, both in MLR assays and in vivo, demonstrating specific acceptance of donor skin grafts. Moreover, we have shown that porcine thymus grafts generate normal, functional human Tregs (Kalscheuer et. al., manuscript submitted). One difference between these models and the clinical situation is that the human T cell compartment did not preexist at the time of porcine thymus transplantation. We therefore examined the ability of swine thymus transplants to engraft and support thymopoiesis in humanized mice with established human immune systems (154). Following peripheral T cell depletion and removal of the human thymus grafts, porcine thymus tissue engrafted under the renal capsule and supported human thymopoiesis and T cell development. These human T cells were specifically tolerant to donor pig antigens and responded to 3rd party pig stimulation in MLR assays. The level of human anti-pig natural antibodies did not increase and even declined in animals with porcine thymus grafts, indicating a lack of sensitization and possible B cell tolerance following thymus transplantation. However, when we performed porcine thymus transplants in GalTKO mice (155), which produce anti-Gal natural antibodies, the engraftment of porcine thymus was significantly reduced in animals with high levels of anti-Gal antibodies. In animals that did accept the porcine thymus tissue, a lack of T cell-dependent antibody sensitization was observed, but B cells producing anti-Gal antibodies in a T cell-independent manner were not tolerized (155). Together, these results indicate that porcine thymus transplants can support human thymopoiesis resulting in a normal T cell repertoire and specific T cell tolerance. However, B cells producing xenoantibodies in a T cell-independent manner are not tolerized and may constitute a barrier to the successful application of this strategy. In contrast, mixed xenogeneic chimerism tolerized T cell-independent B cell responses of all specificities recognizing the donor (see below), suggesting that the combination of xenogeneic thymus transplant and mixed chimerism might be an optimal approach.

B) Large animal models

Thymus transplantation for the induction of allogeneic and xenogeneic tolerance has also been investigated in large animal models. Our initial attempts at allogeneic thymus transplantation in miniature swine demonstrated that the thymus tissue needed to be transplanted as a vascularized tissue to engraft in recipients that were not T cell-depleted (156–158). We have shown that suppressive mechanisms of tolerance to the donor may be involved in xenogeneic thymus graft recipients (155), and others have shown that transplanting vascularized thymus tissue enhances suppressive capacity (159). We therefore developed two strategies for vascularized thymus transplantation. The first was transplantation of a composite “thymokidney” that was prepared by implanting autologous thymus under the kidney capsule and vascularization of the tissue (157, 160). The other method, that could be applicable to any co-transplanted organ, is direct revascularization of a porcine thymus lobe (161). Transplantation of the thymus as a vascularized thymus lobe or as part of a composite thymokidney was shown to support host thymopoiesis (161, 162) and induce tolerance to donor kidneys and hearts across MHC class I and full MHC barriers (158, 162–164).

Xenogeneic thymus transplants have been performed from both Gal+ and GalTKO swine to baboons in an effort to induce tolerance in this preclinical model. When Gal+ porcine thymus tissue was transplanted into T cell-depleted baboons as a non-vascularized graft, the tissue survived for 48 days. While there was not an increase in the level of anti-Gal antibodies, porcine skin graft survival was not prolonged in these recipients, indicating that full tolerance was not achieved (165). Baboons that received vascularized thymus tissue transplants from Gal+ donors, along with T cell depletion and anti-Gal antibody immunoadsorption, had evidence for donor-specific unresponsiveness by MLR assays and evidence for early host thymopoiesis (166, 167). These grafts were all rejected due to the return of anti-Gal antibodies, however. This demonstrated that, similar to the results reviewed above in rodents, high levels of T cell-independent antibodies represent a barrier to thymus transplant survival and B cells producing these antibodies are not tolerized by thymus transplantation. Using vascularized thymus transplants from GalTKO swine, we were able to demonstrate that the lower levels of non-Gal anti-swine antibodies do not lead to thymus rejection. Baboon recipients of thymus plus kidney transplants demonstrated significantly prolonged survival of life-supporting GalTKO swine kidneys, in some cases > 80 days. In contrast, baboon recipients of kidneys without cotransplanted vascularized thymus tissue rejected their kidneys due to induced humoral responses, indicating T cell sensitization (34). No thymus grafts or co-transplanted kidneys were lost due to rejection. Functional analysis of the thymus grafts showed they supported baboon thymopoiesis by demonstration of phenotypic markers of thymocyte maturation and active T cell receptor gene rearrangement in the thymus (168, 169). In vitro, there was evidence for donor-specific T cell tolerance in CML assays. Although there was no induced antibody production and a decrease in the amount of preformed antibody levels in all animals, indicating a lack of T cell sensitization, circulating anti-pig cytotoxic antibodies could be detected at all time points and IgM deposition was seen in the co-transplanted swine kidneys (168). These data correspond to the findings in the rodent models detailed above. Thus, while porcine thymus supported baboon thymopoiesis with in vitro evidence for T cell tolerance, B cell tolerance was not induced. For the elimination of anti-swine antibody responses to be achieved with thymus transplantation, it seems that it must be paired with a strategy designed to induce robust B cell tolerance.

2) Mixed Chimerism for T and B cell tolerance

The association of chimerism with immunological tolerance emerged from the work of Owen and Billingham on Freemartin cattle (170, 171). Since that first report, mixed chimerism induced in adults with pre-existing immune systems has been shown to induce T and B cell tolerance across allogeneic barriers in rodents (172–175) (176) (177), large animals (178–184), and humans (185–191). We have also extensively studied the strategy of inducing mixed chimerism for tolerance induction across the xenogeneic barrier.

A) Rodent models

Our early studies of xenogeneic bone marrow transplantation were performed in a rat-to-mouse model, a combination described as concordant since transplants between these species do not undergo hyperacute rejection (as opposed to discordant transplants that are hyperacutely rejected). Our first attempts at inducing chimerism in this model adopted the nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen used at that time for our allogeneic BMT model (192) that utilized 300 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI), 700 cGy of thymic irradiation (TI), and antibodies depleting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. This regimen failed to induce chimerism across the xenogeneic barrier, however (193). This failure was found to be due to rejection by NK cells and CD4/CD8 double negative γδ T cells, as the addition of depleting antibodies for NK1.1 and Thy-1.2 permitted the induction of xenogeneic chimerism, and there was no requirement for anti-Thy1.2 mAb in mice lacking γδ T cells (92). Additionally, a large number of donor bone marrow cells were required to achieve mixed chimerism in this model, partly due to destruction by preformed anti-rat antibodies in recipient mice (194). However, the effect of these anti-donor natural antibodies could be overcome by administering large doses of donor bone marrow, likely due to adsorption of antibodies on the bone marrow product itself (195, 196). Analysis of the immune responses following the development of xenogeneic chimerism revealed specific prolongation of donor, but not 3rd party rat skin grafts. Further studies indicated that tolerance was associated with the presence of rat bone marrow-derived cells, morphologically resembling dendritic cells, in the recipient thymus and deletion of donor-reactive T cell clones (197, 198). B cell responses in these rat-to-mouse chimeras were also tolerized and chimeric animals lacked induced antibody responses even following secondary skin grafts (199). Despite the achievement of initial engraftment, peripheral chimerism was gradually lost in all animals, decreasing to less that 1% by 28 weeks (94). It was shown that this loss of chimerism was due to a competitive advantage of recipient cells for hematopoiesis in the murine marrow microenvironment and not due to immunological rejection (200, 201). This observation was supported by the later demonstration that chimerism could be boosted by giving a repeat low-dose of TBI and additional donor bone marrow infusion and was not affected by NK cell depletion, suggesting that loss of chimerism was associated with non-immune mechanisms (94). These studies demonstrated that xenogeneic bone marrow could engraft across concordant species barriers and facilitate B cell and T cell tolerance. However, they and in vitro studies in the pig-human combination indicated that provision of species-specific adhesion interactions and growth factors may be required to “even the playing field” between donor and host hematopoietic stem cells if permanent chimerism is to be achieved (202–206).

Our mixed chimerism studies in the rat-to-mouse model also demonstrated that pre-existing, T cell-independent IgM natural antibody-producing B cells were tolerized by the achievement of even low-levels of mixed chimerism (199, 207). The next step toward validating this strategy for tolerance induction across discordant barriers was to prove that mixed chimerism could tolerize the anti-Gal response. To do so, we investigated the ability of allogeneic bone marrow to induce tolerance to the anti-Gal antibody response in GalTKO mice (208). GalTKO mouse recipients of wild-type bone marrow showed significantly reduced levels of anti-Gal antibodies 2 weeks after transplant, and the level became undetectable in the serum at 4 weeks. Since anti-Gal antibody-producing B cells were undetectable by ELISPOT in long-term follow up, it was determined that mixed chimerism resulted in tolerization of anti-Gal producing B cells (209). Further analysis revealed that anti-Gal producing B cells were rendered anergic early after BMT, but long-term unresponsiveness is mediated by clonal deletion and/or receptor editing of xenoreactive B cells (210). In these animals, donor MHC matched, but Gal+, hearts were accepted after the establishment of mixed chimerism in the recipients (211). In murine recipients that had the level of anti-Gal antibody boosted, to simulate situations where human recipients may have high levels of preformed natural antibodies, chimerism could still be achieved, but required a high dose of bone marrow to overcome the preformed antibody response (196). We next induced mixed rat xenogeneic chimerism in GalTKO mice and demonstrated that anti-Gal producing B cells were again tolerized and that all forms of cardiac xenograft rejection, including hyperacute xenograft rejection, delayed xenograft rejection and cell-mediated rejection were prevented by this single strategy (212).

Although mixed chimerism had been demonstrated in concordant species, induction of chimerism across more distant species barriers, such as pig-to-mouse or discordant pig-to-baboon combinations, which would be more relevant to clinical pig-to-human transplants, presents additional challenges. By transplanting porcine BM into immunodeficient SCID mice, we demonstrated engraftment of progenitors and low levels of porcine chimerism (200). Since engraftment was enhanced by adding porcine specific growth factors IL-3, and GM-CSF to the conditioning regimen (213), we developed transgenic mice that expressed porcine hematopoietic cytokines (214). Utilization of these animals as recipients enhanced swine bone marrow engraftment, which was associated with the long-term presence of porcine class II cells in the host thymus (215). These chimeras demonstrated donor-specific skin graft acceptance, donor-specific unresponsiveness in MLR assays and an absence of anti-swine IgG antibodies after skin grafting (216). Finally, using humanized mice with fully developed human immune systems (217), we were able to demonstrate that porcine mixed chimerism induced human T cell tolerance. Porcine chimeric humanized mice lacked anti-donor responses in MLR assays and accepted donor-matched skin grafts, but rejected 3rd party swine skin grafts. Again, T cell tolerance was associated with the presence of porcine class II+ cells in the human thymus graft, suggesting deletional tolerance (218).

These studies in various models repeatedly demonstrate that the induction of mixed chimerism across xenogeneic barriers is possible. Additionally, established mixed chimeras become tolerant to their donor and eliminate preformed anti-donor antibody-producing cells. They also demonstrate the requirement for donor species-specific hematopoietic cell growth factors to reduce the preference for host bone marrow proliferation in the host environment. Additional species-specific growth factors and adhesion molecules could likely further reduce this competitive advantage of host hematopoiesis.

2) Large animal models

The first experiments studying swine transplants to nonhuman primates utilized Gal+ swine as the source of marrow. Likely due in part to the high levels of xenoantibodies in the serum, including anti-Gal, initial experiments failed to show peripheral macrochimerism but did provide evidence for persisting pig DNA, suggesting very low levels of engraftment (219, 220). Since studies in rodents indicated that high numbers of donor hematopoietic cells are required to overcome a pre-existing anti-donor antibody response (212), the next series of studies investigating xenogeneic chimerism in the pig-to-baboon model utilized porcine mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC). Mobilizing the progenitor cells and harvesting by leukapheresis of the donor increased the number of cells administered to recipients increased approximately 100-fold (221). This modification, combined with anticoagulation to prevent platelet activation during infusion (222) and the use of co-stimulatory blockade in the immunosuppressive regimen, resulted in the detection of peripheral chimerism by FACS for up to 5 days in the periphery. One animal that lost chimerism on Day 5 had a rebound of multilineage peripheral chimerism up to 6% on days 16 to 22, suggesting that porcine engraftment had occurred, at least transiently (223, 224). While animals that received PBPCs with costimulatory blockade did not display an induced anti-pig antibody response, they retained anti-Gal antibodies and did not show specific anti-donor T cell tolerance in MLR assays (223, 224). It was concluded that more durable chimerism would be required for this strategy to succeed in this model.

The production of GalTKO swine led to the exploration of these animals as the source of swine bone marrow. We returned to using bone marrow as the source of hematopoietic cells, as opposed to PBPC, because the source animals were being sacrificed at a young age to serve as heart and kidney donors for separate experiments (34, 225), and were too small for leukapheresis (220). The immunosuppressive regimen consisted of TBI (300 cGy), TI (700 cGy), anti-thymocyte globulin for T cell depletion, methylprednisolone, porcine stem cell factor and IL-3, and continuous infusion of mycophenolate mofetil. Despite receiving fewer hematopoietic cells, a recipient had detectible levels of peripheral chimerism in the blood for 5 days, although most of the recipients lost macrochimerism in 2 days. Peripheral microchimerism was also observed in the second week following BMT, suggesting some level of engraftment. In vitro assessment of immune responses revealed that the animals were not sensitized to the donor, as no non-Gal anti-swine antibody developed. Investigations of T cell responses revealed that the animals were hyporesponsive to both donor and 3rd party allogeneic stimulators in MLR, indicating generalized hyporesponsiveness (220, 226). We then modified the regimen to decrease the dose of TBI to 150 cGy and substitute tacrolimus for mycophenolate mofetil, given the known myelosuppressive effects of MMF, in order to augment hematopoietic stem cell engraftment. Although they did not have peripheral chimerism at any time point, two recipients of the regimen showed evidence for donor progenitor cell engraftment for 28 days. BM biopsies taken at that time grew colony-forming units (CFU) of porcine origin as determined by PCR. One animal maintained low cytotoxic titers of anti-swine antibodies until day 28, when it expired before MLR could be performed. The other animal maintained low cytotoxic antibody titers until day 57 and MLR performed at that date indicated donor-specific hyporesponsiveness (227). However, when tolerance induction was tested by performing a combined bone marrow and kidney transplant with the same induction protocol on two subsequent animals, bone marrow engraftment as determined by CFU analysis was not observed and the kidneys were rejected. Together, the data in large animals indicates that other interventions to augment engraftment, including measures to overcome rapid macrophage-mediated destruction of porcine cells, will be required for achievement of durable chimerism and tolerance.

New Frontiers

Although xenogeneic thymus transplantation leads to apparently normal thymopoiesis with positive selection mediated by donor TEC (146), post-thymic maturation of T cells and Tregs may be defective due to a lack of donor MHC in the periphery (Kalscheuer et al., manuscript submitted). Two modifications to the thymus transplant protocol may address this issue. First, host thymic epithelial cells could be harvested at the time of host thymectomy and injected into the porcine graft, allowing for positive selection on host MHC, and normal post-thymic maturation in the periphery by host APC (150). Additionally, the porcine thymus transplant could be combined with porcine bone marrow transplantation, resulting in survival of porcine APC that would in turn allow for normal post-thymic maturation via donor MHC. Since the porcine endothelium constitutively expresses both MHC class I and class II (27, 28), there is also a possibility that xenogeneic thymus transplantation combined with solid organ transplantation would provide adequate T cell/Treg-SLA interactions for post-thymic maturation of donor-restricted T cells. While provision of porcine antigen in the periphery would not lead to effective host MHC-restricted immunity, it could promote effective Treg-mediated suppression of anti-donor responses and permit clearance of infectious organisms affecting donor cells.

There has been considerable interest in the potential to use Tregs to modulate the xenogeneic immune response (27). Two reports have demonstrated that Tregs can be expanded ex-vivo and suppress baboon anti-pig T cell responses (228, 229). The Tregs appeared to be antigen-specific, as suppression of responses to 3rd party pigs was lower than suppression to the same pig used for antigen stimulation during expansion (229). Additionally, Tregs were able to suppress baboon B cell responses following polyclonal stimulation, suggesting they may have some effect on xenogeneic antibody production. One final property of Tregs may have application for tolerance induction in xenotransplantation. Pilat et. al. have demonstrated that ex-vivo expanded Tregs facilitate bone marrow engraftment in mouse allotransplantation experiments and allow for elimination of cytoreductive conditioning in BMT recipients (230). We have applied this strategy in a nonhuman primate BMT model and demonstrated marked prolongation of allogeneic chimerism (Duran-Struuck, Sondermeijer, Sykes et. al. unpublished data). We plan to start investigating the application of Tregs in xenotransplantation and tolerance induction in the near future. Additionally, we expect the hCD47/GalTKO animal to be a better source of donor bone marrow for xenogeneic mixed chimerism, as the cells will be less susceptible to macrophage-mediated destruction.

Our understanding of the immunologic and physiologic hurdles to xenotransplantation has greatly improved over the previous few decades. Many of the obstacles are the result of mismatches in receptor-ligand or enzyme-substrate interactions between the pig tissue and recipient blood and immune systems. Having identified and characterized numerous cell surface proteins and carbohydrates involved, investigators in this field have managed to produce either knockout or transgenic animals with genetic modifications intended to correct these mismatches. However, bringing these modifications together into a single “idealized” source animal has yet to occur. We are hopeful that as more improvements are made and combined, substantial progress will be made towards minimizing the mismatches between the organ transplant and its new environment. Additionally, we continue to see tolerance induction as a critical component to any future clinical application of xenotransplantation. The response of the immune system to the xenograft is unlikely to be sufficiently mitigated by genetic modification alone and will almost certainly to remain a significant barrier. The induction of T cell tolerance has the ability to also regulate the NK cell component of the innate immune system. The ability to induce B cell tolerance may also prove critical, since the identification of many natural antibody targets make it unlikely they can all be nullified by further targeted genetic deletion. The demonstration that Tregs are active in the xenogeneic model suggests the possibility of cellular therapy as an adjunct to systemic immunosuppression or a tolerance induction protocol. The xenogeneic model may be particularly suitable for tolerance induction since all transplants would be pre-planned and donor-specific Tregs could be generated pretransplant. Therefore, despite the obstacles reviewed in this article, we feel that significant progress has been made to overcome the barriers to successful xenotransplantation and remain optimistic that xenotransplantation will be the ultimate solution to the organ transplant shortage.

Table 1.

Contributions of donor and host to tolerance in xenogeneic thymus transplantation and mixed chimerism. TEC: thymic epithelial cells, APC: antigen-presenting cells

| Positive Selection of T cells | Negative Selection of T cells | T cell restriction | Cell types tolerized | Post-thymic maturation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenogeneic Thymus Transplantation | Donor TEC | Donor TEC, APC and Host APC | Donor | T cells | Possibly deficient due to absence of donor MHC in the periphery |

| Mixed Xenogeneic Chimerism | Host TEC | Host TEC, APC and Donor APC | Host | T cells, B cells, NK cells (anergy) | Yes |

Abbreviations

- Gal

α-galactose-1,3-galactose

- GalT

α-1,3-galactosyltransferase

- GalTKO

GalT-knockout

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- SLA

swine leukocyte antigen

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- SIRPα

signal-regulatory protein alpha

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- NeuGc

N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- NHP

nonhuman primate

- CRP

complement regulatory protein

- TCR

T cell receptor

- BMT

bone marrow transplant

- TI

thymic irradiation

- TBI

total body irradiation

- PBPC

peripheral blood progenitor cells

- CFU

colony-forming units

References

- 1.Cameron AM, et al. Social media and organ donor registration: the facebook effect. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013;13:2059–2065. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada K, Griesemer AD, Okumi M. Pigs as xenogeneic donors. Transplantation reviews. 2005;19:164–177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reemtsma K, McCracken BH, Schlegel JU, Pearl M. Heterotransplantation of the Kidney: Two Clinical Experiences. Science. 1964;143:700–702. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3607.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starzl TE, et al. Baboon-to-human liver transplantation. Lancet. 1993;341:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92553-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US guidelines on xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 1999;5:465. doi: 10.1038/8325. Editorial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachs DH. The pig as a potential xenograft donor. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;43:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachs DH, Galli C. Genetic manipulation in pigs. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2009;14:148–153. doi: 10.1097/mot.0b013e3283292549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang YG, et al. Mouse retrovirus mediates porcine endogenous retrovirus transmission into human cells in long-term human-porcine chimeric mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:695–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI21946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fishman JA, Patience C. Xenotransplantation: infectious risk revisited. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2004;4:1383–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Issa NC, et al. Absence of replication of porcine endogenous retrovirus and porcine lymphotropic herpesvirus type 1 with prolonged pig cell microchimerism after pig-to-baboon xenotransplantation. Journal of virology. 2008;82:12441–12448. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01278-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hector RD, Meikle S, Grant L, Wilkinson RA, Fishman JA, Scobie L. Pre-screening of miniature swine may reduce the risk of transmitting human tropic recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:222–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieckhoff B, Petersen B, Kues WA, Kurth R, Niemann H, Denner J. Knockdown of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) expression by PERV-specific shRNA in transgenic pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsoondar J, et al. Production of transgenic pigs that express porcine endogenous retrovirus small interfering RNAs. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cozzi E, Tallacchini M, Flanagan EB, Pierson RN, 3rd, Sykes M, Vanderpool HY. The International Xenotransplantation Association consensus statement on conditions for undertaking clinical trials of porcine islet products in type 1 diabetes--chapter 1: Key ethical requirements and progress toward the definition of an international regulatory framework. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:203–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sykes M, d’Apice A, Sandrin M, Committee IXAE. Position paper of the Ethics Committee of the International Xenotransplantation Association. Transplantation. 2004;78:1101–1107. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000142886.27906.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galili U, Shohet SB, Kobrin E, Stults CL, Macher BA. Man, apes, and Old World monkeys differ from other mammals in the expression of alpha-galactosyl epitopes on nucleated cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:17755–17762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker W, Bruno D, Holzknecht ZE, Platt JL. Characterization and affinity isolation of xenoreactive human natural antibodies. Journal of immunology. 1994;153:3791–3803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMorrow IM, Comrack CA, Sachs DH, DerSimonian H. Heterogeneity of human anti-pig natural antibodies cross-reactive with the Gal(alpha1,3)Galactose epitope. Transplantation. 1997;64:501–510. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199708150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai L, et al. Production of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science. 2002;295:1089–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1068228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelps CJ, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafsson K, Germana S, Hirsch F, Pratt K, LeGuern C, Sachs DH. Structure of miniature swine class II DRB genes: conservation of hypervariable amino acid residues between distantly related mammalian species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:9798–9802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada K, Sachs DH, DerSimonian H. Human anti-porcine xenogeneic T cell response. Evidence for allelic specificity of mixed leukocyte reaction and for both direct and indirect pathways of recognition. Journal of immunology. 1995;155:5249–5256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollins SA, Kennedy SP, Chodera AJ, Elliott EA, Zavoico GB, Matis LA. Evidence that activation of human T cells by porcine endothelium involves direct recognition of porcine SLA and costimulation by porcine ligands for LFA-1 and CD2. Transplantation. 1994;57:1709–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorling A, Lombardi G, Binns R, Lechler RI. Detection of primary direct and indirect human anti-porcine T cell responses using a porcine dendritic cell population. European journal of immunology. 1996;26:1378–1387. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray AG, Khodadoust MM, Pober JS, Bothwell AL. Porcine aortic endothelial cells activate human T cells: direct presentation of MHC antigens and costimulation by ligands for human CD2 and CD28. Immunity. 1994;1:57–63. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sultan P, et al. Pig but not human interferon-gamma initiates human cell-mediated rejection of pig tissue in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:8767–8772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller YD, Ehirchiou D, Golshayan D, Buhler LH, Seebach JD. Potential of T-regulatory cells to protect xenografts. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2012;17:155–161. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283508e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choo JK, et al. Species differences in the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II antigens on coronary artery endothelium: implications for cell-mediated xenoreactivity. Transplantation. 1997;64:1315–1322. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199711150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara H, et al. Human dominant-negative class II transactivator transgenic pigs - effect on the human anti-pig T-cell immune response and immune status. Immunology. 2013;140:39–46. doi: 10.1111/imm.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gock H, Nottle M, Lew AM, d’Apice AJ, Cowan P. Genetic modification of pigs for solid organ xenotransplantation. Transplantation reviews. 2011;25:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phelps CJ, et al. Production and characterization of transgenic pigs expressing porcine CTLA4-Ig. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:477–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plege A, Borns K, Baars W, Schwinzer R. Suppression of human T-cell activation and expansion of regulatory T cells by pig cells overexpressing PD-ligands. Transplantation. 2009;87:975–982. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819c85e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hering BJ, Walawalkar N. Pig-to-nonhuman primate islet xenotransplantation. Transplant immunology. 2009;21:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada K, et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2005;11:32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen G, et al. Acute rejection is associated with antibodies to non-Gal antigens in baboons using Gal-knockout pig kidneys. Nat Med. 2005;11:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davila E, et al. T-cell responses during pig-to-primate xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2005.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yi S, Feng X, Wang Y, Kay TW, Wang Y, O’Connell PJ. CD4+ cells play a major role in xenogeneic human anti-pig cytotoxicity through the Fas/Fas ligand lytic pathway. Transplantation. 1999;67:435–443. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199902150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi S, Feng X, Hawthorne WJ, Patel AT, Walters SN, O’Connell PJ. CD4+ T cells initiate pancreatic islet xenograft rejection via an interferon-gamma-dependent recruitment of macrophages and natural killer cells. Transplantation. 2002;73:437–446. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi S, et al. T cell-activated macrophages are capable of both recognition and rejection of pancreatic islet xenografts. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:2750–2758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benda B, Sandberg JO, Holstad M, Korsgren O. T cells in islet-like cell cluster xenograft rejection: a study in the pig-to-mouse model. Transplantation. 1998;66:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199808270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gill RG, Wolf L, Daniel D, Coulombe M. CD4+ T cells are both necessary and sufficient for islet xenograft rejection. Transplantation proceedings. 1994;26:1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tonomura N, et al. Pig islet xenograft rejection in a mouse model with an established human immune system. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cardona K, et al. Long-term survival of neonatal porcine islets in nonhuman primates by targeting costimulation pathways. Nat Med. 2006;12:304–306. doi: 10.1038/nm1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rayat GR, Gill RG. Pancreatic islet xenotransplantation: barriers and prospects. Current diabetes reports. 2003;3:336–343. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt P, Krook H, Maeda A, Korsgren O, Benda B. A new murine model of islet xenograft rejection: graft destruction is dependent on a major histocompatibility-specific interaction between T-cells and macrophages. Diabetes. 2003;52:1111–1118. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basker M, et al. Clearance of mobilized porcine peripheral blood progenitor cells is delayed by depletion of the phagocytic reticuloendothelial system in baboons. Transplantation. 2001;72:1278–1285. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abe M, et al. Elimination of porcine hemopoietic cells by macrophages in mice. Journal of immunology. 2002;168:621–628. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Navarro-Alvarez N, Yang YG. CD47: a new player in phagocytosis and xenograft rejection. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2011;8:285–288. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ide K, et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H, et al. Attenuation of phagocytosis of xenogeneic cells by manipulating CD47. Blood. 2007;109:836–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strowig T, et al. Transgenic expression of human signal regulatory protein alpha in Rag2−/− gamma(c)−/− mice improves engraftment of human hematopoietic cells in humanized mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:13218–13223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109769108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Navarro-Alvarez N, Yang YG. Lack of CD47 on donor hepatocytes promotes innate immune cell activation and graft loss: a potential barrier to hepatocyte xenotransplantation. Cell transplantation. 2013 doi: 10.3727/096368913X663604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Wang H, Wang S, Fu Y, Yang YG. Survival and function of CD47-deficient thymic grafts in mice. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:160–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tena A, et al. Engraftment and peripheral persistence of human CD47 transgenic porcine progenitor cells in CHEF-NSG mice. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:363–364. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tena A, et al. Initial evidence for functional immune modulation in primate recipients of porcine skin grafts following conditioning with human CD47 transgeneic pig hematopoietic stem cells. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:341. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rood PP, et al. Late onset of development of natural anti-nonGal antibodies in infant humans and baboons: implications for xenotransplantation in infants. Transplant international: official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2007;20:1050–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naziruddin B, et al. HLA antibodies present in the sera of sensitized patients awaiting renal transplant are also reactive to swine leukocyte antigens. Transplantation. 1998;66:1074–1080. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oostingh GJ, Davies HF, Tang KC, Bradley JA, Taylor CJ. Sensitisation to swine leukocyte antigens in patients with broadly reactive HLA specific antibodies. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2002;2:267–273. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz Varela I, Sanchez Mozo P, Centeno Cortes A, Alonso Blanco C, Valdes Canedo F. Cross-reactivity between swine leukocyte antigen and human anti-HLA-specific antibodies in sensitized patients awaiting renal transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2003;14:2677–2683. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088723.07259.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mulder A, et al. Human monoclonal HLA antibodies reveal interspecies crossreactive swine MHC class I epitopes relevant for xenotransplantation. Molecular immunology. 2010;47:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong BS, et al. Allosensitization does not increase the risk of xenoreactivity to alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout miniature swine in patients on transplantation waiting lists. Transplantation. 2006;82:314–319. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000228907.12073.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hara H, et al. Allosensitized humans are at no greater risk of humoral rejection of GT-KO pig organs than other humans. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cooper DK, Tseng YL, Saidman SL. Alloantibody and xenoantibody cross-reactivity in transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000105116.74032.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Byrne GW, et al. Proteomic identification of non-Gal antibody targets after pig-to-primate cardiac xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:268–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Byrne GW, Stalboerger PG, Du Z, Davis TR, McGregor CG. Identification of new carbohydrate and membrane protein antigens in cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:287–292. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203c27d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miwa Y, et al. Are N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Hanganutziu-Deicher) antigens important in pig-to-human xenotransplantation? Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Irie A, Koyama S, Kozutsumi Y, Kawasaki T, Suzuki A. The molecular basis for the absence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:15866–15871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Irie A, Suzuki A. CMP-N-Acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase is exclusively inactive in humans. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;248:330–333. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Breimer ME. Gal/non-Gal antigens in pig tissues and human non-Gal antibodies in the GalT-KO era. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:215–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu A, Hurst R. Anti-N-glycolylneuraminic acid antibodies identified in healthy human serum. Xenotransplantation. 2002;9:376–381. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2002.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burlak C, et al. N-linked glycan profiling of GGTA1/CMAH knockout pigs identifies new potential carbohydrate xenoantigens. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:347. doi: 10.1111/xen.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burlak C, et al. Identification of human preformed antibody targets in GTKO pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2012.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ohdan H, Sykes M. B cell tolerance to xenoantigens. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:98–106. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kawahara T, Ohdan H, Zhao G, Yang YG, Sykes M. Peritoneal cavity B cells are precursors of splenic IgM natural antibody-producing cells. Journal of immunology. 2003;171:5406–5414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu Y, et al. Characterization of anti-Gal antibody-producing cells of baboons and humans. Transplantation. 2006;81:940–948. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203300.87272.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]