Abstract

Background

The prognosis for patients with hepatocellular cancer (HCC) undergoing transarterial therapy (TACE/TAE) is variable.

Methods

We carried out Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors using a training dataset of 114 patients treated with TACE/TAE. A simple prognostic score (PS) was developed, validated using an independent dataset of 167 patients and compared with Child–Pugh, CLIP, Okuda, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) and MELD.

Results

Low albumin, high bilirubin or α-fetoprotein (AFP) and large tumour size were associated with a two- to threefold increase in the risk of death. Patients were assigned one point if albumin <36 g/dl, bilirubin >17 μmol/l, AFP >400 ng/ml or size of dominant tumour >7 cm. The Hepatoma arterial-embolisation prognostic (HAP) score was calculated by summing these points. Patients were divided into four risk groups based on their HAP scores; HAP A, B, C and D (scores 0, 1, 2 and >2, respectively). The median survival for the groups A, B, C and D was 27.6, 18.5, 9.0 and 3.6 months, respectively. The HAP score validated well with the independent dataset and performed better than other scoring systems in differentiating high- and low-risk groups.

Conclusions

The HAP score predicts outcomes in patients with HCC undergoing TACE/TAE and may help guide treatment selection, allow stratification in clinical trials and facilitate meaningful comparisons across reported series.

Keywords: embolization, hepatocellular, prognosis

introduction

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and third most common cause of cancer mortality. Unfortunately, the majority of patients have unresectable disease at presentation, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or bland embolisation (TAE) has been widely used in these cases. Two small, randomised trials and a meta-analysis [1] have demonstrated a survival advantage in carefully selected patients treated with TACE compared with best supportive care, but TACE has not yet been shown to be superior to TAE [2]. Recent guidelines, recommended TACE for patients with intermediate-stage HCC according to the BCLC classification which accounts for ∼20% of patients [3]. However, the intermediate group comprises a wide spectrum in terms of liver function and extent of tumour, and this may explain the large differences in survival reported for individual series [4]. A simple, pragmatic and reliable prognostic index based on objective measures would be of value in providing information to patients, for stratifying patients entering clinical trials and in making meaningful comparisons between series reported in the literature.

The aims of our study were (i) to identify predictors of survival in a cohort of patients undergoing TACE or TAE for unresectable HCC, (ii) to develop and validate a simple scoring system and (iii) to compare the new scoring system with the most frequently used prognostic systems for its ability to separate high- and low-risk patients.

methods and materials

study population

We reviewed 114 sequential patients with HCC treated with TAE/TACE at the Royal Free Hospital and University College Hospital between 1997 and 2010, including patients from a recently reported clinical trial [2]. HCC was diagnosed by histology or imaging according to European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria and patients who had surgery or transplantation were excluded. These patients formed the ‘training dataset’, used to develop the hepatoma arterial-embolisation prognostic (HAP) score.

The HAP score was validated using an external and independent cohort of 167 patients treated with TACE at University Hospital Birmingham NHS Trust (the ‘validation dataset’). Both the centres are liver transplant centres, and TAE/TACE was deemed to be the appropriate treatment modality by a multidisciplinary team.

treatment procedure

In the training dataset, TAE-treated patients were embolised with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (50–150 µm) alone, while TACE-treated patients received either transarterial epirubucin mixed with lipiodol or cisplatin before embolization. In the validation dataset, all patients were treated with TACE based on doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and lipiodol, and PVA was used as the embolic particle. TACE/TAE was repeated thereafter if tumour vascularity persisted, provided the patient tolerated the procedure and there were no emergent contraindications.

statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of first TACE/TAE until death or the date of last follow-up. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression were used to produce crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for potential risk factors. All factors were included in a stepwise backward selection model (with a P value of ≤0.10) to identify a set of factors that together have the best performance. The proportionality assumption was checked using Schoenfeld residuals of the final model. Tumour size and the three biochemical factors [albumin, bilirubin and α-fetoprotein (AFP)], although continuous, were used as binary variables in the Cox models for ease of interpretation of the HRs and application in clinical practice. The cut-offs used were bilirubin 17 μmol/l, albumin 36 g/dl which are, respectively, the upper and lower limits of the normal range; AFP: 400 ng/ml since this has been used as a diagnostic cut-off, and 7 cm for tumour size.

The HAP score was developed using the set of clinical factors that had the best prognostic performance from the multivariable analysis. The minimum follow-up for each patient was 6 months. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and statistical significance tested using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata 12. All reported P values are two-sided.

comparison of different scoring systems to predict mortality

training dataset

Using three different methods, we compared the HAP score with five well-known scoring systems; two scores of liver function: Child–Pugh and Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and three scores which include both liver function and tumour characteristics: Okuda [5], Cancer of Liver Italian Programme (CLIP) [6] and BCLC [7]. Initially, we compared the HRs estimated for each of the scores using Cox regression. We then compared the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curves in order to evaluate the discriminatory ability of these scoring systems to predict OS. Finally, we compared the estimates of the detection rates (DRs) and false-positive rates (FPRs) for death for HAP with the five existing scoring systems in order to evaluate its performance relative to the other five scoring systems. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) for DR and FPR were estimated using the Wilson method.

results

patients

The training and validation sets were similar with respect to most variables (Table 1). The training cohort had a higher proportion of Child–Pugh score B patients, and more patients with a MELD >10. Main-branch portal vein thrombosis was an exclusion criterion for TAE/TACE in both institutions, but segmental portal vein involvement was more common in the validation dataset.

Table 1.

Demographic data for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization or bland embolisation (TACE/TAE)

| Characteristics | Training dataset |

Validation dataset |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Total (N) | N (%) | Total (N) | |

| Age at first session, years (median, range) | 65 (23–84) | 114 | 64 (18–80) | 166 |

| Gender (female/male) | 15/99 (13/87) | 114 | 34/133 (20/80) | 167 |

| Aetiology | 106 | 167 | ||

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) | 17 (16) | 16 (10) | ||

| HCV | 27 (25) | 26 (16) | ||

| Alcohol-related | 16 (15) | 42 (25) | ||

| Other | 46 (43) | 83 (50) | ||

| Child–Pugh class | 114 | 167 | ||

| A | 81 (71) | 151 (90) | ||

| B | 30 (26) | 16 (10) | ||

| C | 3 (3) | 0 | ||

| CLIP score | 96 | 153 | ||

| 0 | 17 (18) | 21 (14) | ||

| 1 | 44 (46) | 58 (38) | ||

| 2 | 26 (27) | 41 (27) | ||

| >2 | 9 (9) | 33 (22) | ||

| Okuda stage | 89 | 155 | ||

| 1 | 59 (66) | 106 (68) | ||

| >1 | 30 (34) | 49 (32) | ||

| MELD score | 95 | 167 | ||

| ≤10 | 37 (39) | 136 (81) | ||

| >10 | 58 (61) | 31 (19) | ||

| BCLC stage | 113 | - | - | |

| A | 39 (35) | |||

| B | 35 (31) | |||

| C | 35 (31) | |||

| D | 4 (4) | |||

| Tumour characteristics | ||||

| Tumour size (mm) | 112 | 154 | ||

| ≤30 | 25 (22) | 22 (14) | ||

| 30–50 | 34 (32) | 54 (35) | ||

| 50–70 | 18 (17) | 32 (21) | ||

| >70 | 32 (29) | 46 (30) | ||

| Tumour volume > 50% | 7 (6) | 108 | 36 (23) | 156 |

| Number of lesions | 113 | 161 | ||

| 1 | 48 (42) | 59 (37) | ||

| ≥2 | 65 (56) | 102 (63) | ||

| α-Fetoprotein (ng/ml) | 102 | 163 | ||

| ≤400 | 70 (69) | 113 (69) | ||

| >400 | 32 (31) | 50 (31) | ||

| Presence of ascites | 18 (17) | 103 | 7 (4) | 159 |

| Segmental portal vein thrombosis | 7 (6) | 114 | 47 (28) | 167 |

| Treatment | 114 | 167 | ||

| TAE | 56 (49) | NA | ||

| TACE | 49 (43) | 167 (100) | ||

| TAE + TACE | 9 (8) | NA | ||

At the time of the analysis, 89 of 114 in the training cohort and 107 of 167 in the validation cohort had died. The median OS was 15.0 (95% CI 9.7–16.6) and 13.7 (95% CI 9.4–16.9) months for the training and validation cohorts, respectively. The median follow-up was 5.7 (95% CI 2.5–6.8) and 1.9 (95% CI 1.2–2.5) years for the two cohorts.

univariable and multivariable cox regression analyses

In both univariable and multivariable analyses, tumour size, albumin, bilirubin and AFP were statistically significant predictors of OS (Table 2). Tumour size was divided into four groups (<3 cm, 3–5 cm, 5–7 and >7 cm). The first three groups were very similar in their survival outcomes in a univariable analysis, whereas the survival outcome of the group with lesions >7 cm was significantly different from the group with lesion size <3 cm (P = 0.008). Therefore, the groups with lesion size ≤7 cm were combined and compared with the group with >7 cm. The Kaplan–Meier OS curves for these four factors are shown in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Although the adjusted HR for creatinine was statistically significant, the effect was small (only 2% decrease in risk for an increase of 1 μmol/l creatinine).

Table 2.

Cox regression analysis of potential risk factorsa

| Risk factors | Univariable |

Multi variable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | No. of deaths/patients | bAdjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age at 1st session | 0.999 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.94 | 89/114 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 0.13 |

| Aetiology | 0.04 | 0.40 | |||

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) | 1 | 16/17 | 1 | ||

| HCV | 0.63 (0.33, 1.24) | 19/27 | 0.60 (0.26, 1.38) | ||

| ALD | 0.32 (0.15, 0.72) | 10/16 | 0.35 (0.11, 1.14) | ||

| Multiple | 0.59 (0.33, 1.06) | 38/46 | 0.52 (0.23, 1.16) | ||

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.002) | 0.13 | 81/106 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.999) | 0.02 |

| INR | 0.09 | 0.33 | |||

| ≤1.2 | 1 | 42/57 | 1 | ||

| >1.2 | 1.48 (0.94, 2.32) | 36/46 | 1.44 (0.75, 2.77) | ||

| Bilirubin (μmol/l) | 0.04 | 0.047 | |||

| ≤17 | 1 | 26/38 | 1 | ||

| >17 | 1.66 (1.02, 2.71) | 47/59 | 2.21 (1.07, 4.56) | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.002 | 0.004 | |||

| ≥36 | 1 | 47/64 | 1 | ||

| <36 | 2.08 (1.31, 3.30) | 34/42 | 3.03 (1.62, 5.69) | ||

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP, ng/ml) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤400 | 1 | 50/70 | 1 | ||

| >400 | 2.89 (1.76, 4.73) | 27/32 | 2.50 (1.24, 5.04) | ||

| Number of lesions | 0.15 | 0.14 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 37/48 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 0.97 (0.54, 1.75) | 16/21 | 1.07 (0.50, 2.32) | ||

| >2 | 1.56 (0.96, 2.54) | 35/44 | 2.18 (1.07, 4.44) | ||

| Size of the largest lesion (mm) | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| ≤70 | 1 | 59/77 | 1 | ||

| >70 | 2.56 (1.55, 4.22) | 25/32 | 2.51 (1.22, 5.19) | ||

ALD, alcoholic liver disease.

aFor patients in the training dataset.

bAdjusted for age, treatment, aetiology, creatinine, INR, albumin, AFP, number of lesions and tumour size. The multivariate analysis was based on 81 patients with 59 deaths.

developing the prognostic score

The HAP scoring system was based on the four most statistically significant predictors of OS in the multivariable analysis; albumin, bilirubin, AFP and tumour size. Patients were assigned one point for each of the four parameters when they were in the adverse group as defined by the cut-off. The HAP score was defined as the sum of these scores, and patients were classified into low- (HAP A), intermediate-(HAP B), high-(HAP C) or very high-(HAP D) risk groups with HAP scores of 0, 1, 2 or >2 points, respectively (Table 3). The equal weighting applied to each factor was justified since the adjusted HRs for the four factors were similar in a multivariable model using just these four factors (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 3.

Calculation of the Hepatoma arterial-embolisation prognostic (HAP) score

| Prognostic factor | Points |

|---|---|

| Albumin < 36 g/dl | 1 |

| AFP > 400 ng/ml | 1 |

| Bilirubin > 17 μmol/l | 1 |

| Maximum tumour diameter >7 cm | 1 |

| HAP classification | Points |

| HAP A | 0 |

| HAP B | 1 |

| HAP C | 2 |

| HAP D | >2 |

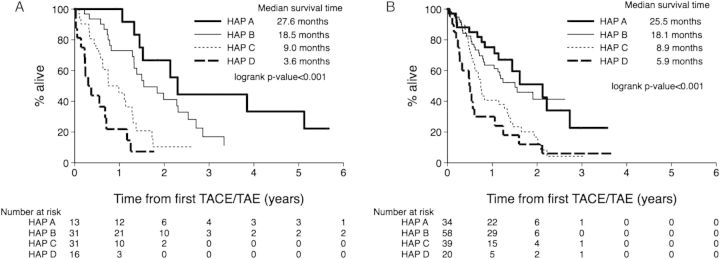

The HAP score could be calculated for 91 patients in the training set and 151 in the validation set (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Kaplan–Meier plots stratified by the HAP score showed statistical evidence for a reduction in OS when moving from HAP A to HAP D in both training and validation sets (P value from the log-rank test: <0.001, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to the Hepatoma arterial-embolisation prognostic (HAP) score in the training dataset (A) and the validation dataset (B). For the training dataset, the median overall survival (OS) times were 27.6 months (95% CI16 to not estimable), 18.5 months (95% CI15.5–30.4), 9.0 months (95% CI 6.9–15.4) and 3.6 months (95% CI 1.7–8.5) for HAP A, B, C and D, respectively. For the validation set, OS median values were 25.5 (95%CI 13.7–32.8), 18.1 (95% CI 9.9 to not estimable), 8.9 (95% CI 6.8–16.1) and 5.9 (95% CI 2.8–12.7) months, respectively.

comparison of different scoring systems

The Child–Pugh, Okuda, CLIP, BCLC and HAP scoring systems, but not MELD, were found to be statistically significant in univariable analyses using the training dataset (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). HRs were the largest for HAP groups C (HR 4.4) and D (HR 10.11) than any other scoring system.

As with the training dataset, univariable analyses for Child–Pugh, Okuda, CLIP, MELD and HAP using the validation dataset revealed the strongest association between the HAP scoring system and survival (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online, HR: 2.45 and 3.54 for HAP groups C and D, respectively). BCLC could not be calculated for the validation dataset since the performance status was not available for these patients.

The discriminatory ability of the various scoring systems to predict mortality was evaluated separately using both the training and validation datasets by comparing the AUROC curve. The analyses were carried out at 1 and 2 years after the first TACE/TAE treatment (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). In the training cohort, the HAP scoring system had the highest AUROC at both time points.

We compared the AUROC of HAP with each of Child–Pugh, Okuda, CLIP, BCLC and MELD in a pairwise manner (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). The difference was statistically significant at 1 year (P ≤ 0.01) for Okuda, CLIP, BCLC and MELD, and close to significance for Child–Pugh. At 2 years, and the difference was significant for Okuda, MELD, BCLC and Child–Pugh, but not so for CLIP. These results combined with the highest AUROC for HAP (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online) suggest HAP as a better scoring system than Child–Pugh, Okuda, BCLC and MELD at 1 and 2 years, and that HAP is better than CLIP at 1 year and is at least as good at 2 years.

Area under the ROC curve was also the highest for HAP at 1 year in the validation dataset (P = 0.02, supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Moreover, pairwise comparisons indicate that the HAP area is significantly different from Okuda, MELD and Child–Pugh at 1 year (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). ROC curves show that for a given value of sensitivity, the HAP scoring system had the lowest false-positive rate (FPR) among all the scoring systems considered with both datasets (data not shown).

Taken together our results show better performance for HAP when compared with Okuda, MELD, BCLC and Child–Pugh and at least as good a performance as CLIP (supplementary Tables S4 and S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online, shows the DRs, FPRs and likelihood ratio (LR) for each scoring method. The LR combines DR and FPR, and the larger the value, the better the prognostic performance. The HAP scoring system had the highest LR at a cut-off of ≥3 (LR = 4.71), with DR = 33% (i.e. a third of patients dying at 1 year had a HAP score ≥ 3), and FPR = 7% (i.e. 7% of those alive at 1 year have HAP ≥ 3). A HAP score ≥ 3 corresponds to the very high risk group (HAP D). The LR for the highest risk groups for Child–Pugh, Okuda, CLIP, MELD and BCLC were 3.14, 2.89, 1.86, 2.86 and 1.29 respectively. Furthermore, although the LRs were similar for HAP ≥ 2 and Okuda ≥1 at 1 year (2.23 versus 2.32) the DR for Okuda ≥ 1 was much lower than that of HAP (78% for HAP and 51% for Okuda).

The HAP scoring system performed similarly with the validation dataset with the highest LR for HAP ≥ 3 out of all the scoring systems considered, except for Okuda (supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

Several staging systems have been developed for the classification of patients with HCC, but none have been specifically developed to predict outcomes of therapy for HCC. Previous studies have compared staging systems for their ability to predict the survival of patients treated with TACE, but there is no consensus as to which is best [8–13]. Moreover, these systems cover the whole clinical spectrum of HCC and are not ideally suited to the TACE-treated subgroup that may fall into a limited range within these classifications.

Against this background, we identified key independent prognostic factors among 114 sequential TAE/TACE-treated patients. Using four factors (albumin, bilirubin, AFP and tumour size) most strongly predictive of survival, we derived a clinical score that stratifies patients into low-, intermediate-, high- and very high-risk groups. The risk factors included in the HAP score are consistent with previous studies. AFP, which may represent a surrogate marker for either tumour bulk or aggressive tumour biology, has frequently emerged as significant in other studies [9,14,15]. Consistent with the findings of Llado et al. [16], we found that AFP levels >400 ng/ml were associated with a threefold increase in the risk of death. Albumin is an index of liver function and parenchymal reserve and has also been identified as prognostic in other studies [15,16]. Tumour size had consistently been shown to influence survival with a larger tumour volume being associated with higher risk of vascular invasion and distant metastasis [14–17]. The threshold above which survival is reduced has varied between 3 and 10 cm, and there is no consensus on which size cut-off should be used [14,15,17–19]. In the present study, patients with largest lesion >7 cm had double the risk of death and 60% reduction in median survival compared with those in whom it was ≤7 cm.

Our analyses suggest that the HAP scoring system predicts survival in TAE/TACE-treated patients better than other scoring systems which have been applied in this population, including Child–Pugh, Okuda, CLIP, BCLC and MELD [8]. Univariable Cox models, examining the association between each of the six scoring systems and survival, produced the largest HRs for HAP and, secondly, the HAP scoring system had the greatest discriminatory ability to predict mortality; it had the highest AUROC and the highest LR, when examining DRs and FPRs.

Alternative prognostic indices have been proposed for TACE patients but suffer from limitations that render them less practical than the HAP score. The index reported by Llado et al. [16] was mathematically more complex and requires the assessment of greater or less than 50% tumour burden in contrast to a simple unidimensional measurement. In another score, the assessment of iodised oil uptake was required but is not applicable with the increasing use of drug-eluting beads that obviate the need for lipiodol [17]. Prognostic indicators that rely on some form of post-embolisation assessment have also been defined, but these are not helpful in pre-selection of patients [20,21].

The implementation and practice of TACE are highly variable between institutions [22], and validation of the HAP score with an independent data set was required to ensure that the score was broadly applicable. It is reassuring that the HAP score was equally discriminatory in the validation cohort despite differences in technique, chemotherapy and patient characteristics. In both the cohorts, a HAP score of C or D defined poor prognosis groups which are unlikely to have benefited from TACE and might now be better served with systemic therapy or supportive care. Overall, the clinical outcomes for these datasets was remarkably similar reflecting common selection criteria, but the application of the HAP score may also help in making meaningful comparisons between published series in which outcomes are more divergent.

In summary, we have defined a simple and clinically relevant prognostic index requiring the measurement of two tumour variables and two liver variables, specifically for patients undergoing TACE. The score performed well against other prognostic staging systems for HCC despite its simplicity, and has been validated on an independent dataset, but it is appropriate to prospectively validate it on a larger cohort to confirm our findings.

funding

This work was supported by the UCLH/UCL Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer T, Kirkwood A, Roughton M, et al. A randomised phase II/III trial of 3-weekly cisplatin-based sequential transarterial chemoembolisation vs embolisation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1252–1259. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raoul JL, Sangro B, Forner A, et al. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CLIP Investigators. A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiades CS, Liapi E, Frangakis C, et al. Prognostic accuracy of 12 liver staging systems in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1619–1624. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000236608.91960.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461–469. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grieco A, Pompili M, Caminiti G, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut. 2005;54:411–418. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DB, Fundakowski CE, Lisker-Melman M, et al. Comparison of MELD and Child–Pugh scores to predict survival after chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1209–1218. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000128123.04554.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testa R, Testa E, Giannini E, et al. Trans-catheter arterial chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with viral cirrhosis: role of combined staging systems, Cancer Liver Italian Program (CLIP) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), in predicting outcome after treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1563–1569. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camma C, Di MV, Cabibbo G, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a comparison of BCLC, CLIP and GRETCH staging systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:62–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savastano S, Miotto D, Casarrubea G, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Child's grade A or B cirrhosis: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:334–340. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Suilleabhain CB, Poon RT, Yong JL, et al. Factors predictive of 5-year survival after transarterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:325–331. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llado L, Virgili J, Figueras J, et al. A prognostic index of the survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Cancer. 2000;88:50–57. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<50::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumortier J, Chapuis F, Borson O, et al. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: survival and prognostic factors after lipiodol chemoembolisation in 89 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueno S, Tanabe G, Nuruki K, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with Child class B and C cirrhosis in relation to treatment: a multivariate analysis of 411 patients at a single center. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:469–477. doi: 10.1007/s005340200058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon RT, Ngan H, Lo CM, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma and postresection intrahepatic recurrence. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:109–114. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(200002)73:2<109::aid-jso10>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillmore R, Stuart S, Kirkwood A, et al. EASL and mRECIST responses are independent prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular cancer patients treated with transarterial embolization. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinato DJ, Sharma R. An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res. 2012;160:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.