Abstract

Background

Since smoking has a profound impact on socioeconomic disparities in illness and death, it is crucial that vulnerable populations of smokers be targeted with treatment. The US Public Health Service recommends that all patients be asked about their smoking at every visit, and that smokers be given brief advice to quit and referred to treatment.

Purpose

Initiatives to facilitate these practices include the 5 A’s (i.e., Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) and Ask Advise Refer (AAR). Unfortunately, primary care referrals are low, and most smokers referred fail to enroll. This study evaluated the efficacy of the Ask Advise Connect (AAC) approach to linking smokers with treatment in a large, safety-net public healthcare system.

Design

Pair-matched-two-treatment arm group-randomized trial.

Setting/participants

Ten safety-net clinics in Houston, TX.

Intervention

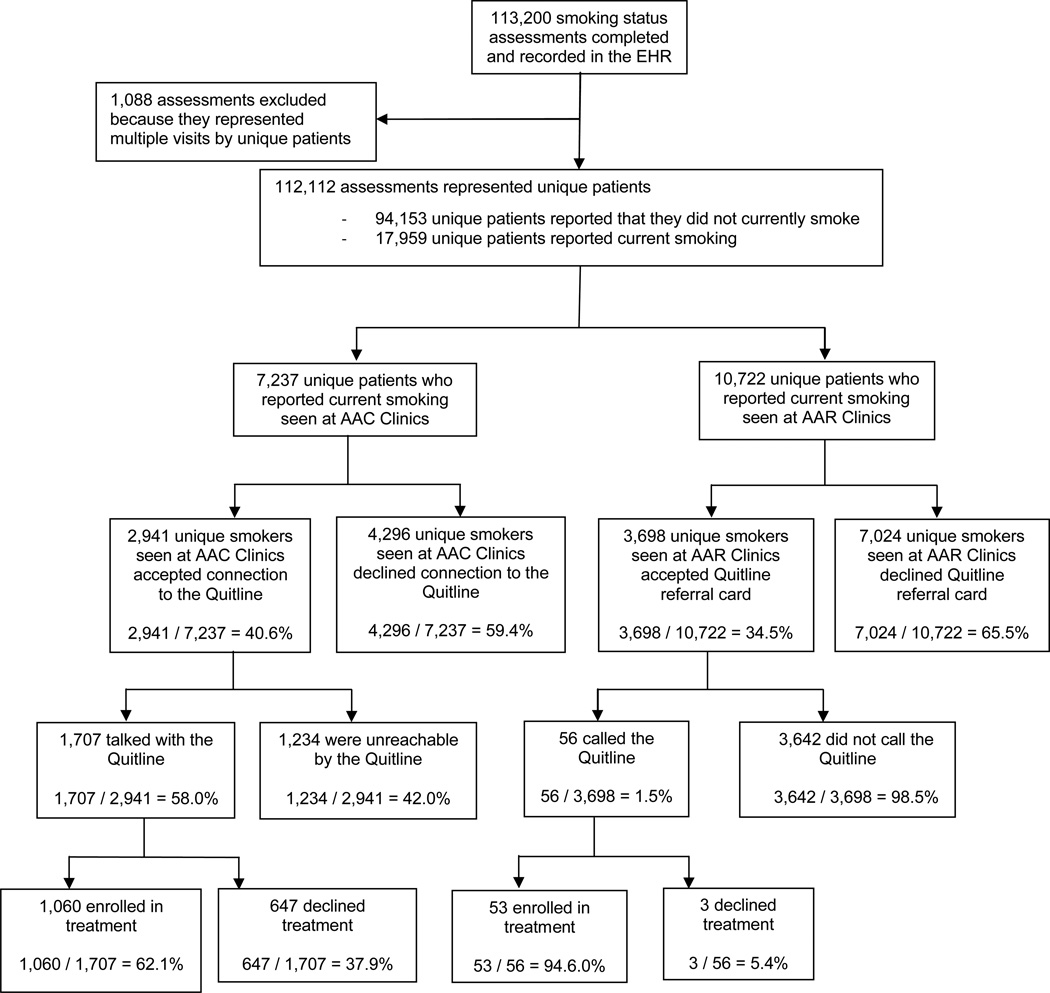

Clinics were randomized to AAC (n=5; intervention) or AAR (n=5; control). Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVNs) were trained to assess and record the smoking status of all patients at all visits in the electronic health record (EHR). Smokers were given brief advice to quit. In AAC, the names and phone numbers of smokers who agreed to be connected were sent electronically to the Texas Quitline daily, and patients were proactively called within 48 hours. In AAR, smokers were offered a Quitline referral card and encouraged to call on their own. Data were collected between June 2010 and March 2012 and analyzed in 2012.

Main Outcome Measure

The primary outcome – impact – was defined as the proportion of identified smokers that enrolled in treatment.

Results

The impact (proportion of identified smokers who enrolled in treatment) of AAC (14.7%) was significantly greater than the impact of AAR (0.5%), t (4) = 14.61, p = 0.0001, OR = 32.10 (95% CI 16.60–62.06).

Conclusions

AAC has tremendous potential to reduce tobacco-related health disparities.

BACKGROUND

Smoking is becoming increasingly concentrated among individuals with the lowest levels of education, income, and occupational status,1–6 and has a profound impact on socioeconomic disparities in the United States.7–9 Therefore, it is crucial that vulnerable populations of smokers be targeted with evidence-based cessation treatment.10 Because evidence-based treatments delivered by quitlines are underutilized,11–15,10,16 formalizing partnerships with healthcare systems has been identified as a critical strategy for enhancing their reach and overall impact.16 Despite 5 A’s (i.e., Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) and “Ask Advise Refer (AAR)” initiatives,12,11,17,18,19,20 treatments have not been well integrated within healthcare systems.10,16,21–24 Thus, there is a critical need to address treatment barriers. We recently evaluated the efficacy of a new, electronic health record (EHR)-based approach to connect smokers in healthcare settings with treatment called “Ask Advise Connect” (AAC). Results of our initial trial, conducted in a private healthcare system, indicated that AAC (vs. AAR) was associated with a 13-fold increase in treatment enrollment.25 The current study utilized similar methodology and was intended to replicate the findings in a safety-net healthcare system.

METHODS

Study Design

A pair-matched group randomized design in 10 Harris Health System community health clinics was utilized. The clinics serve nearly 200,000 unique adult patients per year, 90% are members of racial/ethnic minority groups, and nearly half have incomes below poverty. Five clinics were randomized to AAC (intervention) and five were randomized to AAR (control condition). The dissemination period was 18 months. Data were collected between June 2010 and March 2012 and analyzed in 2012. The protocol was published in 2010.26

Participants

Participants were current smokers ≥18 who were seen the clinics. There was no racial or gender bias in participant selection. IRB approval was obtained from MD Anderson Cancer Center, Harris Health System, and the Texas Department of State Health Services.

Randomization

Randomization occurred at the clinic level. Clinics were initially paired by the investigators based on patient volume, average age, gender, race/ethnicity, and percent below poverty. One clinic within each pair was then randomly assigned to one of the two arms.

Procedures

In AAC and AAR, Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVNs) were trained to assess and record the smoking status of all patients at all visits in the EHR when vital signs were collected. They were also trained to provide smokers with brief advice to quit consistent with the Guideline.11 A 30-minute training session on how to assess smoking status, deliver brief advice to quit, and connect (AAC) or refer (AAR) patients to the Quitline was held at the beginning of the trial. In AAC, LVNs directly connected patients with the Quitline through clicking an automated link in the EHR that sent smokers’ names and phone numbers to the research team, who then sent the information to the Quitline within 24 hours. Patients were contacted by the Quitline within 48 hours. In AAR, LVNs gave smokers willing to accept assistance a Quitline referral card.

Smoking status and willingness to be connected (in AAC) or referred (in AAR) were recorded using the EHR. An Excel data file was automatically and securely sent to the research team daily, and forwarded to the Quitline daily. Treatment enrollment was tracked and recorded by the Quitline. Data were maintained in an Access database.

Outcome Measures: Reach, Efficacy and Impact

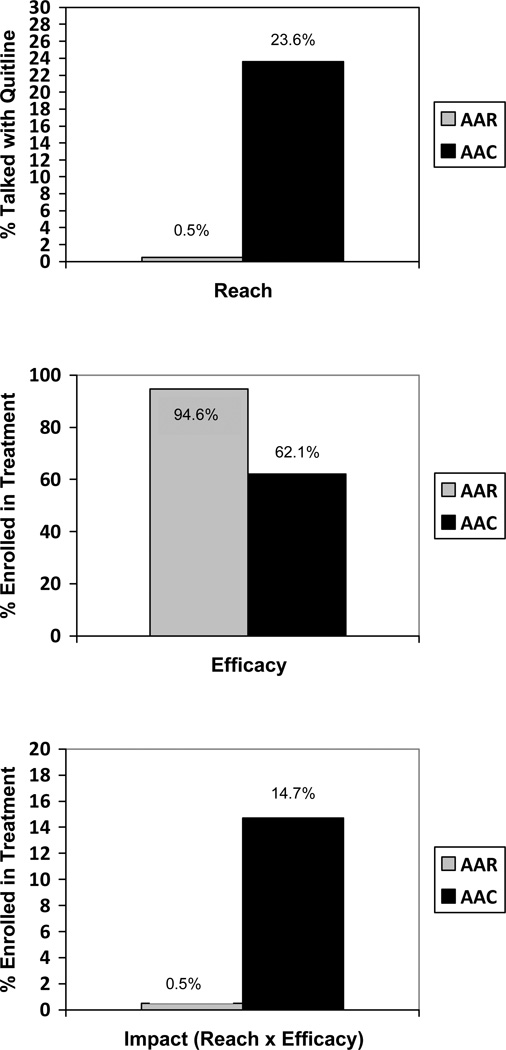

Reach, efficacy, and impact were evaluated using the RE-AIM framework.27 Reach = number of smokers that talked with Quitline / total number of identified smokers. Efficacy = number of smokers that enrolled in Quitline treatment / total number of identified smokers that talked with Quitline. Impact = Reach × Efficacy.

Data Analysis

Proportions for Reach, Efficacy, and Impact were calculated and the magnitude and significance of differences between AAC and AAR were evaluated using Donner and Donald’s weighted empirical logistic transformation approach. This approach accounts for nesting of individuals within clinics and induced intraclass correlation and was used because the data were generated using a pair-matched-two-treatment arm group randomized trial.28 This method accounts for the probability of imbalance between treatment groups on participant characteristics, and provides estimated odds ratios (ORs) for assessing the significance of the intervention effects over all strata.

RESULTS

Smoking prevalence was 16.0% (17,959 / 112,112), and higher in AAC (7,237 / 40,402 = 17.9%) versus AAR (10,722 / 70,710 = 15.2%), Pearson’s X2(1)=142.8 p=1.3×10−33. However, Donner and Donald’s 22 approach accounts for such imbalances and yields results robust to such potential biases.

Reach

In AAC, 7,237 smokers were identified, and in AAR, 10,722 smokers were identified. In AAC, 23.6% of identified smokers talked with the Quitline (1,707 / 7,237) and in AAR, 0.5% of identified smokers talked with the Quitline (56 / 10,722). The empirical logistic transformation approach indicated that the Reach was significantly greater in AAC (vs. AAR), t(4)=18.60, p=.00005.28 The overall estimated odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI for assessing the intervention on Reach over all strata was equal to 56.19 (95% CI 30.79–102.53).

Efficacy

Of the 1,707 smokers that talked with the Quitline in AAC, 1,060 enrolled in treatment (62.1% enrollment rate). Of the 56 smokers in AAR that talked with the Quitline, 53 enrolled in treatment (94.6% enrollment rate). The unconditional test for equivalence of two binomial proportions was used to compare treatment enrollment in AAR versus AAC. The Efficacy of AAR (vs. AAC) was significantly greater (standardized Z statistic = 4.97, p=3.4×10−7.).

Impact

Impact was significantly greater in AAC (23.6% × 62.1% = 14.7%) than in AAR (0.5% × 94.6% = 0.5%), t (4) = 14.61, p = 0.0001.28 The overall estimated OR for assessing the effect of the intervention on impact over all strata was equal to 32.10 (95% CI 16.60–62.06).

CONCLUSIONS

Directly connecting low-income, racially/ethnically diverse smokers to the Quitline via an automated link in the EHR resulted in a nearly 30-fold increase in treatment enrollment compared to providing referral cards and asking smokers to call on their own. This treatment enrollment rate is larger than in any study previously reported. Importantly, AAC yielded a larger effect size in a safety-net healthcare system than a private healthcare system (30-fold vs. 13-fold increase in treatment enrollment).25 Recent healthcare reform legislation has created an environment in which programs such as AAC could be integrated and sustained within healthcare settings.29–31

A strength is that AAC was evaluated in a setting representative of real-world healthcare systems that serve smokers disproportionately burdened by tobacco. Additionally, AAC could be implemented broadly in other healthcare settings. A limitation is that smoking outcome data were not collected, and smokers who called the Quitline may have been more motivated to quit. Another limitation is the absence of a fidelity check on LVNs. That smoking prevalence (16%) was lower than would be expected in this population, and differed between AAC (17.9%) and AAR (15.0%) clinics, suggests that all patients were not for smoking status, and that AAC (vs. AAR) clinics may have more systematically screened and documented smoking status. Finally, the national infrastructure for supporting quitlines would need to be expanded to be sufficient to support widespread adoption of AAC.

In summary, widespread adoption of AAC could reduce tobacco-related morbidity and mortality, and the large effect obtained in a safety-net healthcare system supports the potential of AAC to reduce tobacco-related health disparities.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Figure 2.

Reach, Efficacy, and Impact for AAC and AAR

Notes: Reach = proportion of smokers identified who talked with Quitline; Efficacy = proportion of smokers who talked with Quitlline that enrolled in treatment; Impact = Reach × Efficacy

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Number R18DP001570 (PI: Vidrine) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. This work was also partially supported by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672. MD Anderson’s Patient-Reported Outcomes, Survey, and Population Research (PROSPR) Shared Resource also provided support through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant. Support was also provided by a grant from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment - Center for Community-Engaged Translational Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Jennifer Irvin Vidrine was awarded a grant from the CDC to support the study described in this manuscript (R18DP001570. Her work has also been supported by the NIH and the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT). Dr. Sanjay Shete’s work has also been supported by the NIH and CPRIT. Dr. Yisheng Li’s work has been supported by the CDC and the NIH. Dr. Vance Rabius has served as a consultant on a CDC contract awarded to RTI International and has received funding from the CDC, NIH, and the American Cancer Society. Ms. Penny Harmonson and Mr. Barry Sharp are with the Texas Department of State Health Services, Tobacco Prevention & Control Program, which receives funding from the Texas legislature appropriation of state tobacco settlement and general revenue funds, the CDC, and the FDA. Ms. Cao, Dr. Alford, and Ms. Galindo-Talton have no financial disclosures. Dr. Susan Zbikowski’s work has been supported by the NIH, state agencies, and the CDC. Dr. Zbikowski is an employee of Alere Wellbeing, the service provider for the Texas Quitline. Ms. Lyndsay Miles’s work has been supported by the NIH, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and CPRIT. Ms. Miles is an employee of Alere Wellbeing, the service provider for the Texas Quitline. Dr. David Wetter has received grants from the NIH and CPRIT.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults - Unites States, 2000. MMWR. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Fouladi RT, et al. Understanding the associations among education, employment characteristics, and smoking. Addict Behav. 2005;30:905–914. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:269–278. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:509–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes JR. The future of smoking cessation therapy in the United States. Addiction. 1996;91:1797–1802. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkleby MA. Accelerating cardiovascular risk factor changes in ethnic minority and low socioeconomic groups. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;S7:S96–S103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Hatziandreu EJ, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Educational differences are increasing. Jama. 1989;261:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Hatziandreu EJ, Patel KM, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. The changing influence of gender and race. Jama. 1989;261:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honjo K, Tsutsumi A, Kawachi I, Kawakami N. What accounts for the relationship between social class and smoking cessation? Results of a path analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrams DB. A comprehensive smoking cessation policy for all smokers: Systems integration to save lives and money. In: Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Wallace RB, editors. Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine: National Academies Press; 2007. Appendix A. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Public Health Service (PHS); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Public Health Service (PHS); 2000. Report No.: 1-58763-007-9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation (review) New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S. Quitlines in North America: evidence base and applications. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:201–205. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabius V, McAlister AL, Geiger A, Huang P, Todd R. Telephone counseling increases cessation rates among young adult smokers. Health Psychol. 2004;23:539–541. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:73–78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ask and Act Tobacco Cessation Program. [Accessed May 15, 2013];2013 at http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/clinical/publichealth/tobacco.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cydulka RK, et al. Tobacco control interventions in the emergency department: a joint statement of emergency medicine organizations. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:e417–e426. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ASA Stop Smoking Initiative for Providers: Smoke-Free for Surgery. [Accessed May 15, 2013]; at http://www.asahq.org/For-Members/Clinical-Information/ASA-Stop-Smoking-Initiative.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Do you cAARd? Ask, Advise, Refer - Help your patients quit smoking. [Accessed May 15, 2013];2006 at http://www.caldiabetes.org/content_display.cfm?contentID=497&CategoriesID=32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, Fleming L, Hollis JF, McAfee T. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM, Khanchandani HS, Goodman MJ. Repeated tobacco-use screening and intervention in clinical practice: health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz DA, Muehlenbruch DR, Brown RB, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Effectiveness of a clinic-based strategy for implementing the AHRQ Smoking Cessation Guideline in primary care. Prev Med. 2002;35:293–301. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Silverman CB, et al. Measuring provider adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines: a comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S35–S43. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:458–464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidrine JI, Rabius V, Alford MH, Li Y, Wetter DW. Enhancing dissemination of smoking cessation quitlines through T2 translational research: a unique partnership to address disparities in the delivery of effective cessation treatment. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16:304–308. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181cbc500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donner A, Donald A. Analysis of data arising from a stratified design with the cluster as unit of randomization. Statistics in medicine. 1987;6:43–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. HR-3590 United States. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health. Title XIII of Division A and Title IV of Division B United States. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buntin MB, Jain SH, Blumenthal D. Health information technology: laying the infrastructure for national health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1214–1219. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]