Short abstract

The uterine suspensory tissue (UST), which includes the cardinal (CL) and uterosacral ligaments (USL), plays an important role in resisting pelvic organ prolapse (POP). We describe a technique for quantifying the in vivo time-dependent force-displacement behavior of the UST, demonstrate its feasibility, compare data from POP patients to normal subjects previously reported, and use the results to identify the properties of the CL and USL via biomechanical modeling. Fourteen women with prolapse, without prior surgeries, who were scheduled for surgery, were selected from an ongoing study on POP. We developed a computer-controlled linear servo actuator, which applied a continuous force and simultaneously recorded cervical displacement. Immediately prior to surgery, the apparatus was used to apply three “ramp and hold” trials. After a 1.1 N preload was applied to remove slack in the UST, a ramp rate of 4 mm/s was used up to a maximum force of 17.8 N. Each trial was analyzed and compared with the tissue stiffness and energy absorbed during the ramp phase and normalized final force during the hold phase. A simplified four-cable model was used to analyze the material behavior of each ligament. The mean ± SD stiffnesses of the UST were 0.49 ± 0.13, 0.61 ± 0.22, and 0.59 ± 0.2 N/mm from trial 1 to 3, with the latter two values differing significantly from the first. The energy absorbed significantly decreased from trial 1 (0.27 ± 0.07) to 2 (0.23 ± 0.08) and 3 (0.22 ± 0.08 J) but not from trial 2 to 3. The normalized final relaxation force increased significantly with trial 1. Modeling results for trial 1 showed that the stiffnesses of CL and USL were 0.20 ± 0.06 and 0.12 ± 0.04 N/mm, respectively. Under the maximum load applied in this study, the strain in the CL and USL approached about 100%. In the relaxation phase, the peak force decreased by 44 ± 4% after 60 s. A servo actuator apparatus and intraoperative testing strategy proved successful in obtaining in vivo time-dependent material properties data in representative sample of POP. The UST exhibited visco-hyperelastic behavior. Unlike a knee ligament, the length of UST could stretch to twice their initial length under the maximum force applied in this study.

Keywords: uterine suspensory tissue, cardinal ligament, uterosacral ligament, viscoelasticity, pelvic organ prolapse

1. Introduction

Pelvic floor dysfunction has resulted in 11% of American women undergoing surgery during their lifespan [1]. Over 200,000 prolapse operations are performed each year; this is as many as for breast cancer and more than twice as many as for prostate cancer [2]. The annual estimated cost for prolapse surgery exceeds US $1 billion [3].

Pelvic organ support involves the dynamic interaction between support provided by the levator ani muscles and the connective tissues that attach the organs to the pelvic walls [4]. Vaginal birth can damage those muscles (e.g., Ref. [5]), and it has been noted that pelvic organ prolapse typically occurs in women 20–30 years after having delivered children vaginally [6]. It is possible that repetitive loading and age-related deterioration of the connective tissues loaded over that time might contribute to the subsequent failure. Although subject to debate, many clinicians will support the fact that most women complain of worsening prolapse symptoms at the end of an active day [7]. Therefore, it is important to understand the material properties of the connective tissue in a time- and load history-dependent mechanical setting. This can help us better understand risk factors for prolapse, such as in women who perform repetitive heavy lifting, the effect of the second stage of labor, as well as the fact that pelvic organ prolapse develops rather late in a woman's life and is likely multifactorial in nature.

The uterine suspensory tissue, comprised of the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, is thought to play an important role in resisting pelvic organ prolapse [8]. The CL and USL constitute part of the level I support for the pelvic floor [9]. The CL originates from the pelvic side wall at the top of the greater sciatic foramen to its insertion on the genital tract, centered on the cervix and upper vagina [10]. The USL originates from sacrum and sacrospinous ligament-coccygeus muscle and inserts on the genital tract [10]. There are four ligament structures in total: one CL and one USL on either side of the uterus (Fig. 1).

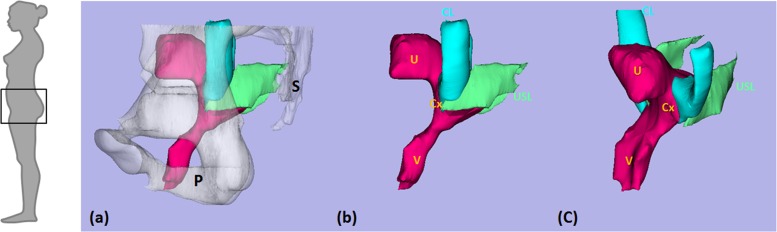

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of female uterine suspensory tissue in a 3D model based on MRI of a healthy control. Note the pelvis (P) and sacrum (S) are transparent in (a) and have been deleted in (b), as viewed from the left, and in (c) in a left oblique view. U denotes uterus; Cx: cervix; V: vagina; CL: cardinal ligament; and USL: uterosacral ligament. Modified from Luo, et al. [11] © Luo, Ashton-Miller, and DeLancey.

Viscoelastic behavior has been observed in many soft tissues including pelvic floor tissues [6,12], so one might anticipate finding it in the CL and USL. Viscoelastic behavior of the CL and USL in living women with prolapse has yet to be quantified. Although the CL and USL are ligaments in name, their composition is not type 1 collagenous tissue as in skeletal ligaments (e.g., Ref. [13]). Instead, they are visceral ligaments similar to a mesentery and comprised of varying combinations of blood vessels, nerves, smooth muscle, and areolar tissue [14–17]. Moreover, considerable variation exists in the spatial morphology of different parts of these structures [18]. Therefore, excision of one region of these “ligaments” would not necessarily provide a sample that is representative of the whole structure. Rather than excising tissue, we chose to first test the force-deflection behavior, or geometric stiffness, of the intact structural complex in vivo recognizing certain constraints (i.e., testing to failure would be contraindicated and long “ramp and hold” times would be infeasible in a busy clinic or operating room).

The objective of this study, therefore, was to (1) describe a technique to quantify the in vivo time-dependent force-displacement behavior of the uterine suspensory tissue complex, (2) demonstrate the feasibility of making these measurements, (3) compare data from POP patients to normal subjects previously reported, and (4) introduce a biomechanical modeling approach for identifying the properties of the CL and USL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Apparatus.

To apply the test force while simultaneously recording the cervical displacement in descent, we developed a tripod mounted computer-controlled linear servo actuator with a force transducer in series (Fig. 2). This apparatus was approved by the Biomedical Electronics Unit of the Human Research Protection Program at the University of Michigan. It consists of a linear servo actuator (model No. FA-PO-150-12-8”, Firgelli Automation, Inc., Vancouver, Canada) to apply force and obtain position information, a Transducer TechniquesTM load cell (Temecula, CA, model No. TLL-500, capacity 500 lb, nonlinearity 0.25% of rated output) at the end of the servo actuator arm to measure the traction force, a motor control unit to move the arm forward and backward at a given speed, and a data acquisition unit to acquire the test data using a microprocessor and a LabVIEW® program. The force measurement was calibrated using weights. The displacement measurement accuracy was confirmed when we videotaped the first nine testing trials with a ruler in the view. Overall, the resolution for the force measurement was 0.0625 lb and for displacement measurement was 0.1 mm. Both measurements were accurate to within 1%. For electrical safety, the testing equipment was powered via an isolation transformer. In addition, an emergency power cut-off switch was included in the motor control unit.

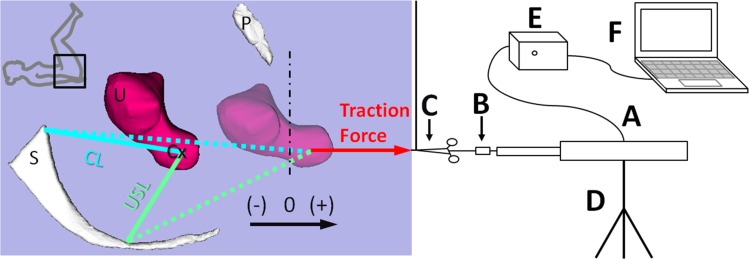

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the test setup. Zero indicates the location of the hymen, with –/+ meaning above or below the hymen. S denotes sacrum; U: uterus; P: pubic bone; and Cx: cervix. A, B and C denote the servo actuator, force transducer, and surgical tenaculum, respectively; D the tripod; E the motor controller; and F the microprocessor. Vertical dashed-dotted line represents the initial location of the hymenal ring. This defines the origin (“0”) for the pelvic organ prolapse measurement system used to assess uterine position. The dashed long and short lines represent the CL and USL, respectively, under load. Note the 1 m long vertical suture suspending the weight of C © Luo, Ashton-Miller, and DeLancey.

2.2. Study Subjects.

Fourteen women with varying degrees of pelvic organ prolapse and a uterus in situ were selected for surgery. They represented a subset from an ongoing University of Michigan institutional review board-approved (IRB No. HUM00056743) study of pelvic organ prolapse. All subjects had symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse below the hymen based on the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system [19]. None of the subjects had previously undergone prior pelvic floor surgery.

2.3. Testing Procedure.

The testing procedure was modeled after clinical assessment of uterine descent during a routine surgical procedure when a tenaculum was placed on the cervix and manual traction was applied in a caudal direction to test the uterine suspensory ligaments (Fig. 2).

The POP-Q values were measured by the study team prior to the induction of anesthesia. After the subject was anesthetized in the operation room, she was placed in the dorsal lithotomy position (inset, Fig. 2). The location of the cervix before and after tenaculum placement was measured by measuring the distance from the lateral cervix to the hymeneal ring (–/+ defined as above/below the hymen). The motor displacement and absolute location recorded by the linear motor was, therefore, aligned with the hymen and considered to be “0” (Fig. 2).

In each patient three ramp and hold test trials were applied with 60 s rest interval between each trial. The ligaments are unloaded in lithotomy position at rest and, therefore, uterine position is arbitrary. Thus, a 1.1 N (or 1/4 lb) preload was applied to remove slack in the uterine suspensory ligaments; this was set based on the senior author's clinical experience and proved to be sufficient during the trials. To make the measurement consistent with each patient, the force was then increased by initiating a “ramp” displacement with a rate of 4 mm/s until the force limit of 17.8 N (or 4 lb) was reached. This latter value is safely below the maximum force used clinically [20,21]. Due to time limitations in the operating room, the subsequent “hold” time (when the displacement was held constant), was restricted to 60 s.

2.4. Data Analysis.

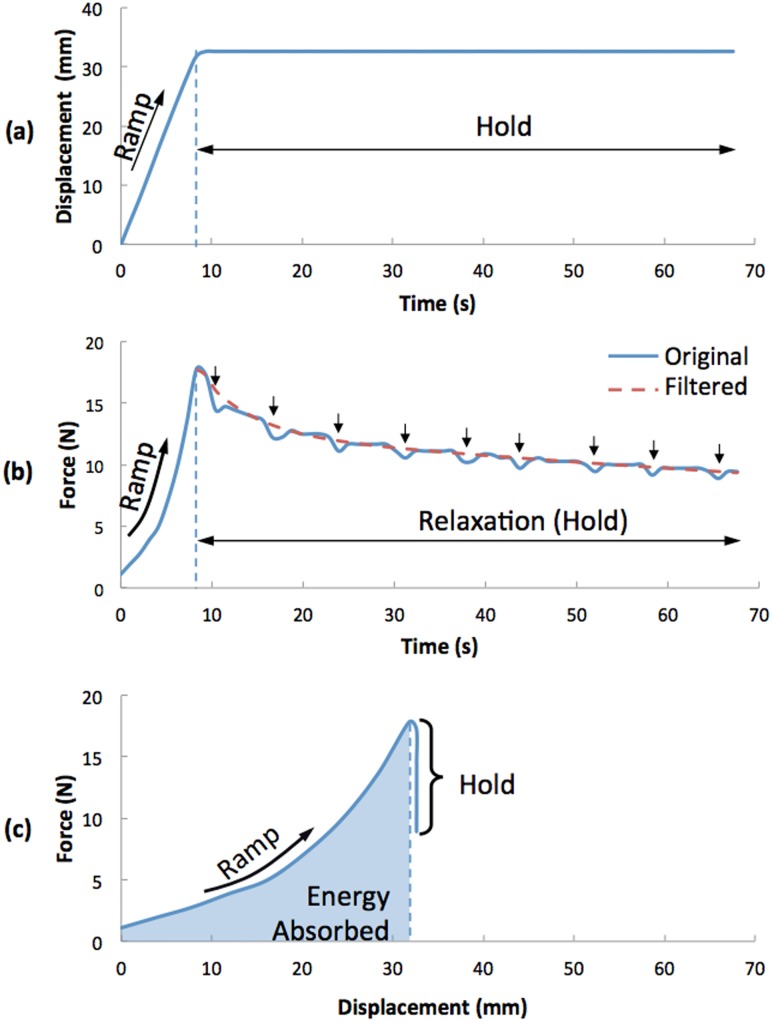

A typical ramp and hold test result for UST is presented to help make the description of the data analysis methods easier to follow (Fig. 3). The test result for each trial was analyzed to calculate the geometric UST stiffness (Stiffness = ΔF/ΔD, F is force, D is displacement, ΔF is the difference between maximum and minimum forces, and ΔD is the displacement difference between maximum and minimum forces) and energy absorbed (, E is energy, and s is displacement) during the ramp phase (from minimum force 1.11 N to maximum force 17.8 N). To check the feasibility of the testing, the ramp data of our prolapse subjects is graphically compared to a cohort or patients without prolapse on whom a manual pull technique was used [20]. Using the data from the hold phase, we obtained tissue relaxation behavior by first filtering the force data with a high pass filter to attenuate the effect of changes in intra-abdominal pressure generated by the respirator (Fig. 3(b)), then normalizing the data by dividing by the peak ramp force; the normalized final force was then compared across trials and patients.

Fig. 3.

Results from a typical “ramp and hold” test of UST (Study ID S005, trial 1). (a) shows displacement versus time, (b) force versus time, and (c) force versus displacement. In (b), arrows indicate respiratory cycles wherein the downward force created by lung expansion caused a temporary force decrease.

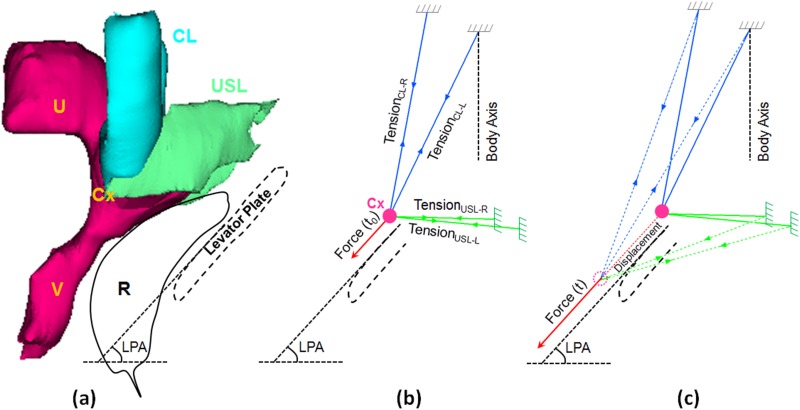

Experimental data were input into a four-cable biomechanical model to predict the material properties and elongation of the CL and USL (Fig. 4) based on the assumption that their origins remain unchanged and the insertions moved together. With the resting position based on the in vivo model geometry provided by (magnetic resonance) MR studies [22], we calculated the axial force and elongation of each cable. The main resting geometry data included the average angle between the CL (54 deg), the average angle between USL (46 deg), the average angle between CL and body axis (18 deg), the average angle between USL and body axis (92 deg), and the average straight length of CL (47.5 mm) and USL (26.5 mm) [22]. The direction in which the uterus moves is also influenced by the dorsal portion of the levator ani muscle called the “levator plate” and intervening rectum. The average levator plate angle (LPA) for prolapse subjects is 53 deg [23]. For the calculation, we also assumed the CL and USL are both symmetric and have the same length and angle on both sides of the uterus, and at rest, there was no difference for the ligament length between prolapse and healthy subjects based on the result from our previous study [24].

Fig. 4.

MR-based four-cable 3D biomechanical model of UST. (a) Cardinal ligament (CL), uterosacral ligament (USL), uterus (U), cervix (Cx), vagina (V), and outline of rectum (R) and levator plate. At right (b) are shown the four-cable free body diagram at time 0 and time t (c). The applied test force was assumed to be parallel to the levator plate. LPA denotes levator plate angle.

As seen in the typical testing result (Fig. 3(c)), the UST exhibits nonlinear hyperelastic behavior. The nonlinear hyperelastic behavior of CL and USL was fit by an exponential force and elongation equation [4]

| (1) |

where C 1 and C 2 are material properties constants, and l 0 and l are the ligament initial length and current length.

For the hold (relaxation) test, we normalized the force divided by the peak force and then fit the normalized reduced force relaxation behavior using a form of Prony series during the 60 s hold

| (2) |

with fitting constraints g 1, g 2, τ 1, and τ 2 > 0, and G(0) = 1.

Descriptive statistical analysis and two-sided T-test analyses were used with a p value of 0.05 being considered significant.

3. Results

The demographics for the 14 women with prolapse were of 53.9 ± 11.9 (mean ± SD) years, parity of 2.9 ± 1.2, and BMI of 29.1 ± 4.7 kg/m2. The respiration rates were 10.2 ± 1.6 cycles per minute. The POP-Q values revealed that the cervix lay (–) 3.1 ± 4.3 cm above the hymen during maximal Valsalva. On the anterior vaginal wall, a point 3 cm above the hymen at rest was 0.4 ± 1.5 cm below the hymen during maximal Valsalva and the similar point on the posterior wall was 1.6 cm above the hymen during Valsalva (± 1.2 cm). Overall, the anterior vaginal wall lay 1.2 cm below the hymen (± 2.5 cm) and the lowest point of the posterior wall that was at least 3 cm from the hymen at rest was located 1.0 cm above the hymen during maximal Valsalva (± 2.3 cm).

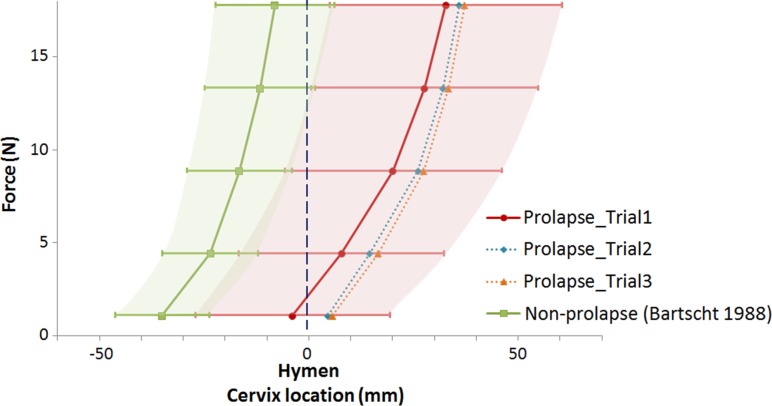

The UST stiffness for these women with prolapse (Figs. 5 and 6) was 0.49 ± 0.13 N/mm for trial 1, 0.61 ± 0.22 N/mm for trial 2 and 0.59 ± 0.2 N/mm for trial 3. For comparison to trial 1, average UST stiffness in women without prolapse was 0.62 N/mm (see Ref. [20], Fig. 5). The force-displacement curves for the women with prolapse (Fig. 5) were shifted to the right compared to the women without prolapse, especially in trial 3, reflecting differences in the cervix starting position. Because the raw subject-specific data for the women without prolapse are no longer available, we could only make a graphical comparison between the two groups.

Fig. 5.

Force and displacement behavior of prolapse women (trial 1, 2, and 3) compared to women without prolapse (Bartscht and DeLancey) displayed as mean and SD (whisker plot and shaded area). The data are shown in interval format for comparison with the Bartscht and DeLancey results

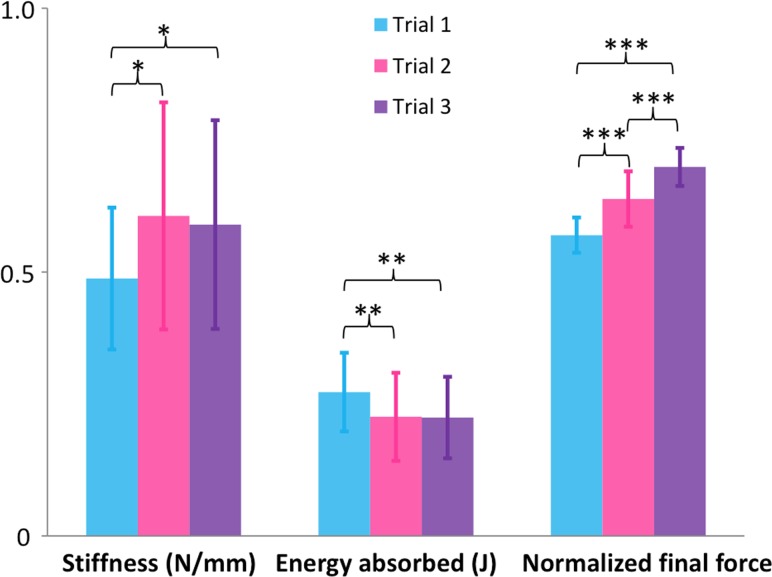

Fig. 6.

UST geometric stiffness, energy absorbed, and normalized final force by trial

The energy absorbed by the UST (Fig. 6) significantly decreased from trial 1 (0.27 ± 0.07 J or N*m) to trial 2 (0.23 ± 0.08 J) and 3 (0.22 ± 0.08 J), but not so from trial 2 to 3. The decreasing values show the UST becoming stiffer after repeated loadings, and the normalized final relaxation force (Fig. 6) significantly increased from trial 1 (0.57 ± 0.03 or 57% of maximum force applied in this study) to trial 2 (0.64 ± 0.05) and trial 3 (0.70 ± 0.04).

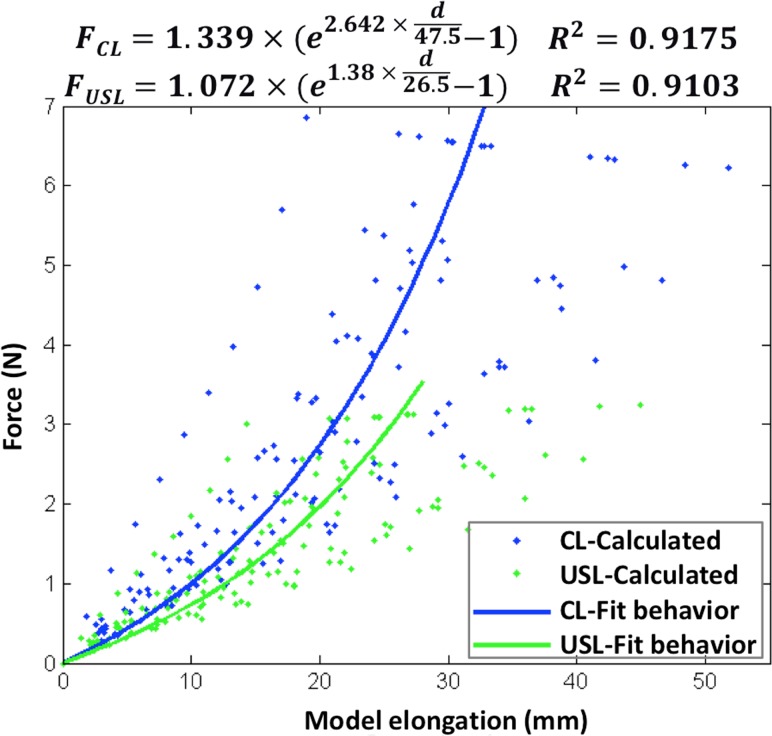

While the cervix was pulled at maximum loading force 17.8 N, the calculated tensile force on each CL was 6.92 ± 0.18 N and on USL was 3.34 ± 0.07 N. The stiffness for each CL is 0.20 ± 0.06 N/mm, and USL is 0.12 ± 0.04 N/mm. For each CL and USL cable, the calculated data and fit hyperelastic behavior is shown in Fig. 7. Compared to the lengths of CL and USL at rest, the CL elongated about 73 ± 20% and the USL elongated about 109 ± 32%, while the cervix was pulled under the maximum force applied in this study.

Fig. 7.

Fit hyperelastic properties of CL/USL

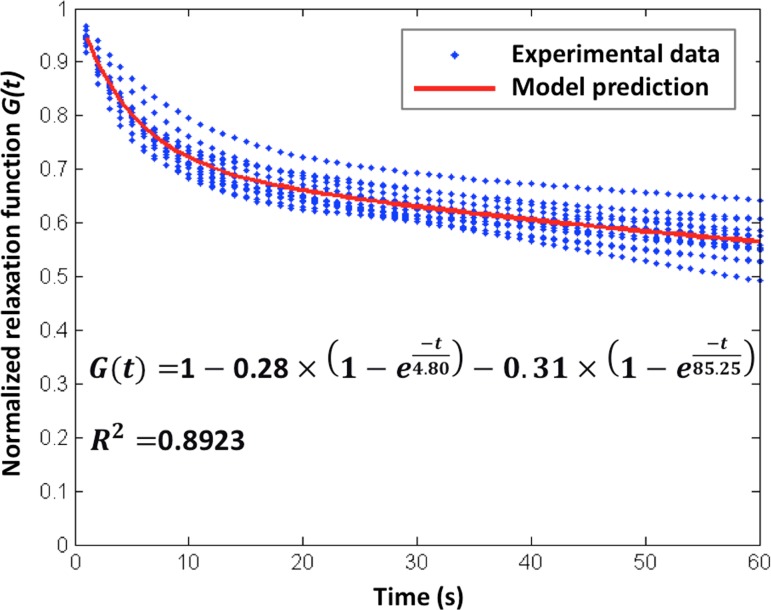

While the relaxation force was divided by the peak force for normalization, the uterine support complex or each ligament has the same normalized relaxation behavior (Fig. 8). The peak force dropped by 20 ± 3% after 5 s and by 44 ± 4% after 60 s, which shows the mechanical behavior of CL and USL are time-dependent.

Fig. 8.

The fitted normalized force relaxation function for UST, CL, and USL during the hold phase

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of the use of a computer controlled servo actuator to measure in situ data on UST stiffness in vivo and infer the properties of the CL and USL in women with prolapse. It provides the first estimates of viscoelastic properties of UST in vivo and in situ under controlled test conditions using multiple trials.

The method presented in this study extends and refines the present in vivo/in situ strategy [20] of visually recording cervical displacement data with a ruler at only four levels of manually applied force without control on how rapidly the test force was applied. Obtaining continuous cervical location data using a controlled loading rate in the ramp and hold phases facilitates accurate measurements of UST stiffness and viscoelastic effects.

UST stiffness (0.49 N/mm) was modestly lower in these women with prolapse compared to stiffness seen in normal women of 0.62 N/mm (Bartscht and DeLancey [20]). The greatest difference between women with prolapse and normal support was seen in 3 cm the lower position of the cervix in women with prolapse at low force (1.11 N) compared with women with normal support suggesting that the ligaments in women with prolapse are longer than those with normal support. Modeling of the separate hyperelastic properties of the cardinal versus the uterosacral ligaments showed that the cardinal ligament displayed a slightly higher stiffness than the uterosacral ligament. When considering the biomechanical model, we only modeled the data from trial 1 since it represents how the UST structures might respond to a single loading cycle, as imposed by a single powerful cough or sneeze. In addition, in the clinic the UST properties are usually evaluated using a single pull.

Several groups have assessed the biomechanical properties of the UST ex vivo. None have assessed in vivo/in situ time-dependent properties of the UST. Reay Jones et al. performed uniaxial tension testing of a 1 by 1 cm sample of uterosacral ligament excised immediately adjacent to the uterus, measured the resilience (area under the force-displacement curve or energy absorbed), and demonstrated a significant resilience difference between control (mean: 0.019 J) and prolapse patients (mean: 0.004 J) [25]. The above study demonstrated that the maximum elongation (plastic limit) of USL was less than 5 mm (or less than 50%) under maximum load (∼15 N), an elongation substantially less than our results and making the measured resilience one order of magnitude less than our results. The difference could be due to the sample itself and preconditioning of the sample. Rivaux et al. similarly performed uniaxial tensile testing on nonprolapsed fresh cadaveric uterosacral biopsies and demonstrated a nonlinear stress-strain relationship and hyperelastic mechanical behavior [26]. The nonlinear hyperelastic behavior of their study is consistent with our results, although we need to further study to measure the cross-sectional area of the intact ligaments and then calculate the stress-strain behavior. Martins et al. also performed uniaxial ex vivo tensile testing of 2 by 1 cm samples of nonprolapsed intermediate regions of uterosacral ligaments and demonstrated a nonlinear stress-strain relationship and hyperelastic behavior [27]. However, these studies are limited by their ex vivo technique and by measuring properties of small excised samples, which may not take into account the significant regional variation in anatomy over the length of the ligaments [25,26].

Although much can be learned from the biology of excised tissues, mechanical testing on small samples needs to be correlated with in vivo/in situ data because the CL and USL are visceral ligaments comprised of many different types of tissue (see Introduction). Therefore, any excised sample may not adequately represent the composition of the entire structure. The present results can be used to verify computer simulations of pelvic floor behavior, which potentially could predict the occurrence of pelvic organ prolapse. It could be useful to directly compare results from excised tissues with results inferred from the four-cable model to better understand the relationship between the two if the composition of the samples is known. Current research suggests that tissue remodeling of the vagina and its supportive tissues, including the metabolism of collagen and elastin and other proteolytic enzymes, occur in response to different environmental stimuli such as the time-dependent effects of loading and unloading [28]. Anatomic studies have demonstrated altered tissue composition in women with prolapse compared to normal women; however, it is unclear whether the altered tissue is a cause or effect of pelvic organ displacement [29,30]. Our study could be complementary to ongoing research regarding tissue-specific changes in the pelvic floor (e.g., Refs. [28,31]) and would provide a broad context into which these findings can be placed.

Review of Fig. 5 shows that the lower position of the uterus is highly influenced by the starting position of the uterus. This suggests that the CL and USL are longer in women with prolapse. Our underlying hypothesis concerning prolapse is that damage to the levator ani muscle during vaginal birth results in increased repetitive forces on the CL and USL over time [4,32]. During the 10–30 years that usually elapse between the muscle injury and development of prolapse, repeated stresses placed on these viscoelastic tissues could lead to tissue remodeling that would produce the longer ligament implied by the lower starting position, emphasizing the importance of time dependent factors.

As with any new testing strategy, our technique will require refinement over time. Limitations of our study include a modest sample size, nonstandardized anesthetic technique, and the graphical comparison to the early data from the control group. This comparison will be more meaningful when a control group is tested using the present methods. Second, it is important to recognize that while this technique seeks, to the extent possible, to isolate the UST properties, it may also include supporting level 2 paravaginal tissues [9]. Third, we used a pulling technique that may measure something different from uterine descent during a maximal Valsalva maneuver. Understanding the relationship between these data and clinical findings will take further research. Fourth, due to the OR setting, only a few minutes were available for each trial. We understand that the 60 s of relaxation might not be enough to identify the long term relaxation behavior. Similarly, the 60 s of rest time between the three trials might also be too short to permit full tissue recovery. Currently, we have no way of knowing whether a greater number of trials, a longer rest time, and longer relaxation time might influence the results or not. Fifth, it is a limitation that we were unable to include sensitivity analyses by which the test parameters were systematically varied to determine which parameters have the greatest influence on the results. Again, there simply was not enough time in the OR to run such tests. Sixth, it is possible that there is an anesthetic effect on smooth muscle tone properties in this study that has yet to be evaluated. Seventh, there was the periodic effect of small changes in abdominal pressure (see Fig. 3(b)) generated by the respirator on the force record; however, the filtering attenuated its effect on the results. Eighth, we developed and employed a simplified four-cable biomechanical model to predict the mechanical behavior of each single ligament based on average geometric data. One might instead create patient-specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based 3D models to calculate the mechanical behavior of each ligament.

This study provides much-needed quantitative data concerning the stiffness, time-dependent behavior of the CL and USL. These insights and data can now be used by design engineers in planning new types of surgical implants, which imitate the function of UST to treat prolapse, verifying FE models of the pelvic floor under load, understanding the cause of pelvic organ prolapse, and testing the hypothesis that inadequate uterine support is a major issue. Our data emphasize the differences between these visceral ligaments and skeletal ligaments. It is noteworthy that our results show that the stiffness of UST in these women (0.49 N/mm) is three orders of magnitude less than that of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee (200 N/mm [13]). In addition, under the maximum force applied in this study, the strains of CL and USL reached up to about 100%, thereby doubling the original length. This is an order of magnitude greater strain than is found in a knee ligament (i.e., less than 10% [33]). Because the uterine suspensory “ligaments” are innately different than ligaments found in the extremities, it is important to quantify their mechanical behavior so as not to apply imply incorrect properties by analogy.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health Office for Research on Women's Health, Specialized Center of Research: Sex and Gender Factors Affecting Women's Health, Grant P50 HD 044406 and NIH R01 HD 038665.

Contributor Information

Jiajia Luo, Biomechanics Research Laboratory, Department of Mechanical Engineering, 2350 Hayward Street, GG Brown Building 3212, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109;; Pelvic Floor Research Group, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, e-mail: jjluo@umich.edu

Tovia M. Smith, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; Pelvic Floor Research Group, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

James A. Ashton-Miller, Biomechanics Research Laboratory, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; Pelvic Floor Research Group, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

John O. L. DeLancey, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; Pelvic Floor Research Group, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

References

- [1]. Olsen, A. L. , Smith, V. J. , Bergstrom, J. O. , Colling, J. C. , and Clark, A. L. , 1997, “Epidemiology of Surgically Managed Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence,” Obstet. Gynecol., 89(4), pp. 501–506. 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Boyles, S. H. , Weber, A. M. , and Meyn, L. , 2003, “Procedures for Pelvic Organ Prolapse in the United States, 1979–1997,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 188(1), pp. 108–115. 10.1067/mob.2003.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Subak, L. L. , Waetjen, L. E. , Van Den Eeden, S. , Thom, D. H. , Vittinghoff, E. , and Brown, J. S. , 2001, “Cost of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery in the United States,” Obstet. Gynecol., 98(4), pp. 646–651. 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01472-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Chen, L. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , Hsu, Y. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2006, “Interaction Among Apical Support, Levator Ani Impairment, and Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse,” Obstet. Gynecol., 108(2), pp. 324–332. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000227786.69257.a8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kearney, R. , Miller, J. M. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2006, “Obstetric Factors Associated With Levator Ani Muscle Injury After Vaginal Birth,” Obstet. Gynecol., 107(1), pp. 144–149. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000194063.63206.1c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2009, “On the Biomechanics of Vaginal Birth and Common Sequelae,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng., 11, pp. 163–176. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Pearce, M. , Swift, S. , and Goodnight, W. , 2008, “Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Is There a Difference in POPQ Exam Results Based on Time of Day, Morning or Afternoon?,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 199(2), pp. 200.e1–200.e5. 10.1016/J.Ajog.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Summers, A. , Winkel, L. A. , Hussain, H. K. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2006, “The Relationship Between Anterior and Apical Compartment Support,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 194(5), pp. 1438–1443. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. DeLancey, J. O. , 1992, “Anatomic Aspects of Vaginal Eversion After Hysterectomy,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 166(6 Pt 1), pp. 1717–1724. 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Ramanah, R. , Berger, M. B. , Chen, L. Y. , Riethmuller, D. , and DeLancey, J. O. L. , 2012, “See It in 3D! Researchers Examined Structural Links Between the Cardinal and Uterosacral Ligaments,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 207(5), pp. 437.e1–437.e7. 10.1016/J.Ajog.2012.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Luo, J. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. L. , 2011, “A Model Patient: Female Pelvic Anatomy can be Viewed in Diverse 3-Dimensional Images With a New Interactive Tool,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 205(4), pp. 391.e1–391.e2. 10.1016/J.Ajog.2011.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Fung, Y. , 1993, Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues, 2nd ed., Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Woo, S. L.-Y. , Hollis, J. M. , Adams, D. J. , Lyon, R. M. , and Takai, S. , 1991, “Tensile Properties of the Human Femur-Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Tibia Complex the Effects of Specimen Age and Orientation,” Am. J. Sports Med., 19(3), pp. 217–225. 10.1177/036354659101900303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Campbell, R. M. , 1950, “The Anatomy and Histology of the Sacrouterine Ligaments,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 59(1), pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Range, R. L. , and Woodburne, R. T. , 1964, “The Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Transverse Cervical Ligament,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 90, pp. 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Cole, E. E. , Leu, P. B. , Gomelsky, A. , Revelo, P. , Shappell, H. , Scarpero, H. M. , and Dmochowski, R. R. , 2006, “Histopathological Evaluation of the Uterosacral Ligament: Is This a Dependable Structure for Pelvic Reconstruction?,” BJU Int., 97(2), pp. 345–348. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05903.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Ramanah, R. , Berger, M. B. , Parratte, B. M. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2012, “Anatomy and Histology of Apical Support: A Literature Review Concerning Cardinal and Uterosacral Ligaments,” Int. Urogynecol. J., 23(11), pp. 1483–1494. 10.1007/s00192-012-1819-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Vu, D. , Haylen, B. T. , Tse, K. , and Farnsworth, A. , 2010, “Surgical Anatomy of the Uterosacral Ligament,” Int. Urogynecol. J., 21(9), pp. 1123–1128. 10.1007/s00192-010-1147-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Bump, R. C. , Mattiasson, A. , Bo, K. , Brubaker, L. P. , DeLancey, J. O. , Klarskov, P. , Shull, B. L. , and Smith, A. R. , 1996, “The Standardization of Terminology of Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 175(1), pp. 10–17. 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Bartscht, K. D. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 1988, “A Technique to Study the Passive Supports of the Uterus,” Obstet. Gynecol., 72(6), pp. 940–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Foon, R. , Agur, W. , Kingsly, A. , White, P. , and Smith, P. , 2012, “Traction on the Cervix in Theatre Before Anterior Repair: Does It Tell Us When to Perform a Concomitant Hysterectomy?,” Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol., 160(2), pp. 205–209. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Chen, L. , Ramanah, R. , Hsu, Y. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2013, “Cardinal and Deep Uterosacral Ligament Lines of Action: MRI Based 3D Technique Development and Preliminary Findings in Normal Women,” Int. Urogynecol. J., 24(1), pp. 37–45. 10.1007/s00192-012-1801-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Hsu, Y. , Summers, A. , Hussain, H. K. , Guire, K. E. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2006, “Levator Plate Angle in Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse Compared to Women With Normal Support Using Dynamic MR Imaging,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 194(5), pp. 1427–1433. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Luo, J. , Betschart, C. , Chen, L. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2013, “Using Stress MRI to Analyze the 3D Changes in Apical Ligament Geometry From Rest to Maximal Valsalva: A Pilot Study,” Int. Urogynecol. J. (in press). 10.1007/s00192-013-2211-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Reay Jones, N. , Healy, J. , King, L. , Saini, S. , Shousha, S. , and Allen-Mersh, T. , 2003, “Pelvic Connective Tissue Resilience Decreases With Vaginal Delivery, Menopause and Uterine Prolapse,” Br. J. Surg., 90(4), pp. 466–472. 10.1002/bjs.4065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Rivaux, G. , Rubod, C. , Dedet, B. , Brieu, M. , Gabriel, B. , and Cosson, M. , 2013, “Comparative Analysis of Pelvic Ligaments: A Biomechanics Study,” Int. Urogynecol. J., 24(1), pp. 135–139. 10.1007/s00192-012-1861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Martins, P. , Silva-Filho, A. L. , Fonseca, A. M. , Santos, A. , Santos, L. , Mascarenhas, T. , Jorge, R. M. , and Ferreira, A. M. , 2013, “Strength of Round and Uterosacral Ligaments: A Biomechanical Study,” Arch. Gynecol. Obstet., 287(2), pp. 313–318. 10.1007/s00404-012-2564-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Moalli, P. A. , Shand, S. H. , Zyczynski, H. M. , Gordy, S. C. , and Meyn, L. A. , 2005, “Remodeling of Vaginal Connective Tissue in Patients With Prolapse,” Obstet. Gynecol., 106(5 Pt 1), pp. 953–963. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000182584.15087.dd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Gabriel, B. , Watermann, D. , Hancke, K. , Gitsch, G. , Werner, M. , Tempfer, C. , and Zur Hausen, A. , 2006, “Increased Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 in Uterosacral Ligaments Is Associated With Pelvic Organ Prolapse,” Int. Urogynecol. J., 17(5), pp. 478–482. 10.1007/s00192-005-0045-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Ewies, A. A. , Al-Azzawi, F. , and Thompson, J. , 2003, “Changes in Extracellular Matrix Proteins in the Cardinal Ligaments of Post-Menopausal Women With or Without Prolapse: A Computerized Immunohistomorphometric Analysis,” Hum. Reprod., 18(10), pp. 2189–2195. 10.1093/humrep/deg420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Rahn, D. D. , Ruff, M. D. , Brown, S. A. , Tibbals, H. F. , and Word, R. A. , 2008, “Biomechanical Properties of the Vaginal Wall: Effect of Pregnancy, Elastic Fiber Deficiency, and Pelvic Organ Prolapse,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 198(5), pp. 590.e1–590.e6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Chen, L. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and DeLancey, J. O. , 2009, “A 3D Finite Element Model of Anterior Vaginal Wall Support to Evaluate Mechanisms Underlying Cystocele Formation,” J. Biomech., 42(10), pp. 1371–1377. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Lipps, D. B. , Oh, Y. K. , Ashton-Miller, J. A. , and Wojtys, E. M. , 2012, “Morphologic Characteristics Help Explain the Gender Difference in Peak Anterior Cruciate Ligament Strain During a Simulated Pivot Landing,” Am. J. Sports Med., 40(1), pp. 32–40. 10.1177/0363546511422325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]