Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia involves alterations in hippocampal function. The implications of these alterations for memory function in the illness remain poorly understood. Furthermore, it remains unknown how memory is impacted by drug treatments for schizophrenia. The goal of this study was to delineate specific memory processes that are disrupted in schizophrenia and explore how they are affected by medication. We specifically focus on memory generalization - the ability to flexibly generalize memories in novel situations.

Methods

Individuals with schizophrenia (n=56) and healthy controls (n=20) were tested on a computerized memory generalization paradigm. Participants first engage in trial-by-error associative learning. They are then asked to generalize what they learned by responding to novel stimulus combinations. Individuals with schizophrenia were tested on or off anti-psychotic medication, using a between-subject design that eliminates concerns about learning-set effects.

Results

Individuals with schizophrenia were selectively impaired in their ability to generalize knowledge, despite having intact learning and memory accuracy. This impairment was found only in individuals tested off medication. Individuals tested on medication generalized almost as well as healthy controls. This between-group difference was selective to memory generalization.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that individuals with schizophrenia have a selective alteration in the ability to flexibly generalize past experience towards novel learning environments. This alteration is unaccompanied by global memory defect. Additionally, the results indicate a robust generalization difference based on medication status. These results suggest that hippocampal abnormalities in schizophrenia may be alleviated with anti-psychotic medication, with important implications for understanding adaptive memory-guided behavior.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Hippocampus, Memory, Antipsychotic drugs, Human

INTRODUCTION

Considerable evidence suggests that individuals with schizophrenia display subtle, but consistent, memory impairments [1, 2]. However, individuals with schizophrenia are not impaired on all forms of memory [1, 3]. Furthermore, the effect of treatment on memory impairments in schizophrenia remains poorly understood at both the cognitive and neurobiological levels. Thus, a central challenge is to characterize the specificity of the memory impairments in schizophrenia, their relation to specific neural systems, and their modulation by anti-psychotic drugs (APDs).

One aspect of memory function that may be particularly vulnerable in schizophrenia is the ability to flexibly generalize memories from past events when encountering novel situations in the future. Understanding how memories may guide behavior in novel situations provides insight into a fundamental aspect of adaptive human behavior. Emerging evidence suggests that in healthy individuals, generalization of memories depends critically on the hippocampus [4-6], a brain region widely known to support the formation of accurate declarative memories [7-9]. Here, we examine the hypothesis that individuals with schizophrenia are specifically impaired at memory-based generalization, and we explore how generalization is impacted by treatment with APDs.

There are a number of reasons to expect that memory generalization might be impaired in schizophrenia and may be impacted by APDs. Extensive evidence suggests that schizophrenia is associated with abnormal hippocampal function. Reductions in hippocampal volume [10, 11], increases in hippocampal perfusion (e.g., rCBF) [12, 13], and reductions in task-associated activations in the hippocampus [14, 15] are found in schizophrenia, along with impaired performance on hippocampal-dependent memory tasks [1, 2]. A particularly strong link has been found between hippocampal function and memory generalization in schizophrenia using a transitive inference paradigm [1, 2]. Transitive inference is a form of hippocampal-dependent generalization in which learned information is used to later guide logical inferences. Individuals with schizophrenia (tested on medication) are impaired at transitive inference, and their impairment is related directly to hippocampal dysfunction [16]. However, it is neither known how memory-based generalization may be impacted by APDs, nor is it known how these findings relate to other forms of generalization that do not rely on logical inference.

Evidence suggesting that generalization may be impacted by APDs comes from recent reports that generalization may also depend on dopaminergic mechanisms in the midbrain [6]. For example, in one study, healthy participants engaged in a novel two-phase learning and generalization task while being scanned with fMRI. In this paradigm, the first phase involved feedback-based learning of a series of associations. In the second phase, subjects were probed to generalize what they learned to novel stimulus combinations. Here, generalization does not depend on logical inference, but on associative memory processes that take place during learning [6]. FMRI data revealed that in this context the ability to generalize involved correlated activation in the hippocampus and in midbrain dopaminergic regions (ventral tegmental area; VTA) during learning, suggesting a cooperative hippocampal-midbrain interaction that supports generalization. The precise anatomical underpinnings of this interaction remain to be determined. However, VTA dopamine neurons are known to project directly to the hippocampus [17-19], where dopamine modulates hippocampal plasticity [20, 21], suggesting a likely mechanism by which midbrain dopaminergic signals may modulate hippocampal representations.

These findings in healthy individuals raise questions regarding the effects of APDs on memory-based generalization. APDs are known to antagonize dopamine (as well as other monoamine receptors) [22]. Thus, one possibility is that APDs may worsen generalization performance. However other evidence demonstrates that dopamine antagonism generally reduces symptoms in schizophrenia [23, 24], raising the possibility that APDs might improve generalization of memories. Indeed, one early report indicated that APDs improve verbal memory performance on a recent memory task. However, because that study did not specifically examine generalization, it remains unknown how, or whether, APD treatment impacts generalization in schizophrenia. Understanding the effects of APDs on memory and generalization is important from both a clinical and basic science perspective, as such understanding may provide insight into possible mechanisms underlying memory-based generalization in the illness.

The goal of the present study was to address two main open questions. First, we sought to examine the effect of schizophrenia on a memory generalization paradigm that does not depend on logical inference. Based on prior reports [25], we predicted that individuals with schizophrenia would be impaired at generalization. Second, we sought to determine the effects of APDs on generalization in schizophrenia in order to distinguish the effects of disease from the effects of medication on this fundamental cognitive process. To that end, we tested generalization in individuals with schizophrenia who were either on or off their medication. Given that the effect of APDs on hippocampal function is largely unknown, we explored whether APDs would impair, facilitate, or have no effect on generalization performance. Importantly, the generalization paradigm used here allows for separate assessments of (a) learning, (b) memory retention, and (c) memory-guided generalization. Therefore, to the extent that APDs impact generalization, this paradigm allows us to determine whether their effect is specific to generalization or is more global, broadly impacting memory function.

METHODS

Subjects

The effects of APDs on generalization were examined using a between-subject design to avoid effects of order and learning-set which are common in studies of learning and memory. Results are reported from 56 volunteers with schizophrenia and 20 healthy control volunteers at the UTSW Schizophrenia Research Clinic.

Patients were tested either on anti-psychotic medication (SV-on; n=20) or off anti-psychotic medication (SV-off; n=16). All volunteers were recruited from the Dallas metropolitan area, the healthy controls through advertising and the schizophrenic volunteers through advertising and directly at a community mental health clinic. We solicited informed consent, validated potential diagnosis and group placement, and subsequently tested all normal volunteers and most schizophrenic volunteers at the UTSW Research Clinic; volunteers were tested with the behavioral task within two weeks of consenting. Additional information regarding patient recruitment, medication status, and exclusion criteria are found in Supplement 1

All patient volunteers received a thorough diagnostic workup using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis (SCID) and met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Consensus diagnoses were based on all available psychiatric information and made by at least two experienced research psychiatrists. Ratings for psychosis (i.e., Positive and Negative Symptom Scale, PANSS) were conducted by three trained research coordinators whose inter-rater reliability was r=0.84, intraclass correlation (Edel, 1957). Informed consent was obtained for all participants in accordance with procedures approved by the UTSW Institutional Review Board.

Ages of the volunteers ranged from 18 to 59 years. Control volunteers (NV) averaged 39.9 years of age (SD=11.8 years) and were not different from either SV-on (mean=40.4; SD=9.1; p=0.85) or SV-off (mean=36.4; SD=11.9, p=0.40), nor were there differences in age between the SV-on and the SV-off (p=0.18). The ages for disease onset for all SV volunteers was between 21 and 27 years of age. The education level of the control group was 14.0 years (SD=1.8), which was not significantly different from the SV-on (mean=13.7; SD=2.7, p=0.55). The education level of SV-off was 11.9 years (SD=2.1), which was lower than the level of the NV (P=0.003), and, to a lesser extent, the SV-on (p=0.04). Of the 20 controls, 19 were administered the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) in predicting IQ; 36 of the 40 SV-on and 13 of the 16 SV-off were also administered the WTAR for predicting pre-morbid IQ; this measurement yielded significant differences between NV (mean=107; SD=8.4) and both SV-on (mean=98; SD=12.2, p=0.001) and SV-off (mean=96; SD=10.9, p=0.001), but no significant differences in predicted pre-morbid IQ between the SV-on and SV-off (p=0.65).

Patient assessments included the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale for symptom severity (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987, the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological status (RBANS; Randolf et al., 1993), and the Birchwood Social Functioning Scale (SFS; Birchwood et al., 1990). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Consistent with their medication status, the SV-off scored significantly higher than the SV-on with respect to the total PANSS score (t(35)=2.57, p=0.014), and on PANSS-general score (t(35)=3.10, p=0.004). The groups did not differ on other measures.

Table 1.

Demographic and neuropsychological measures for all participants.

| NV (n=20) | SZ-ON (n=40) | SZ-OFF (n=16) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N male/female | 5/15 | 26/14 | 12/4 |

| Age (years) | 39.9 (11.8) | 40.4 (9.1) | 36.4 (11.9)) |

| Education (years) | 14.0 (1.84) | 13.7 (2.7) | 11.9 (2.9) |

| Chlorpromazine equivalent (mg) |

- | 483.5 (404.4) | - |

|

| |||

| PANSS | |||

| Total | - | 81.07 (10.8) | 92.43 (8.8) |

| Positive | - | 21.30 (4.3) | 23.3 (5.8) |

| Negative | - | 19.20 (4.7) | 22.3 (4.1) |

| General | - | 40.63 (5.7) | 47.8 (4.8) |

|

| |||

| RBANS | |||

| Total | - | 80.05 (17.8) | 73.9 (17.9) |

| Immediate Memory | - | 88.84 (24.0) | 80.5 (21.9) |

| Visuospatial/Constructual | - | 79.07 (18.5) | 75.2 (14.9) |

| Language | - | 88.12 (12.0) | 89.8 (10.7) |

| Attention | - | 81.42 (18.5) | 75.6 (22.6) |

| Delayed Memory | - | 81.91 (22.3) | 74.0 (20.7) |

|

| |||

| SFS | |||

| Total | 156.6 (16.3) | 118.9 (27.9) | 113.9 (24.6) |

| Social Withdrawal | 13.1 (1.8) | 9.52 (2.6) | 8.27 (2.72) |

| Interpersonal functioning | 8.7 (0.46) | 6.57 (1.7) | 6.36 (2.16) |

| Independence (performance) |

34.9 (3.3) | 28.8 (6.7) | 20.8 (6.6) |

| Independence (competence) |

38.5 (1.1) | 32.0 (5.7) | 31.7 (4.35) |

| Recreational activities | 24.6 (6.0) | 18.1 (7.6) | 12.5 (6.9) |

| Prosocial activities | 28.8 (10.4) | 18.2 (8.5) | 12.7 (8.5) |

| Employment/Occupation | 9.8 (0.5) | 5.19 (3.8) | 2.0 (2.2) |

|

| |||

| WTAR predicted IQ | 107.2 (8.38) | 97.6 (12.21) | 96.0 (10.9) |

Task Stimuli and Procedures

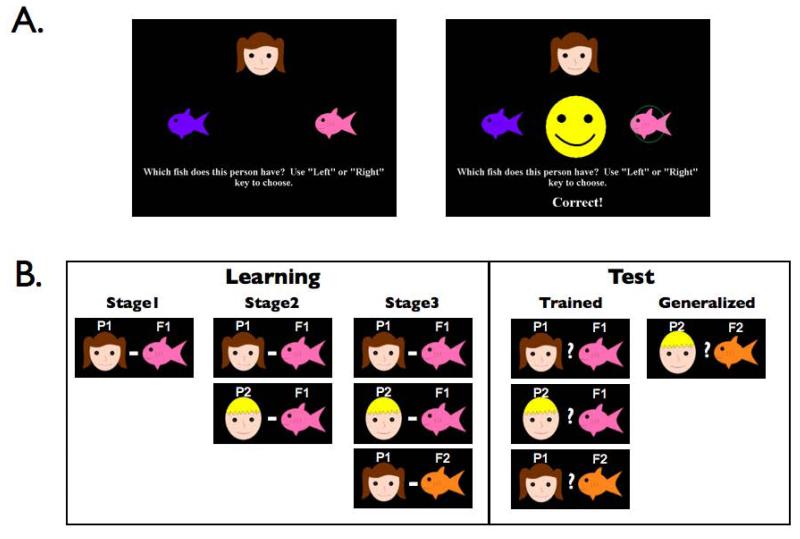

We used an “acquired equivalence” task, which has been previously shown to be sensitive and specific to hippocampal function [25-27]. As shown in Figure 1, the task consisted of two phases. Subjects first engage in associative learning (Learning Phase) and then are tested on generalization (Test Phase)[25-27]. During the Learning phase, participants use trial-by-error feedback to learn associations between stimuli (cartoon faces and colored fish). Although each person-fish association is learned individually, there is partial overlap between them, such that two different people are associated with the same fish (P1-F1; P2-F1). This overlap provides participants with the opportunity to form an associative link between the two people (P1 and P2), even though they have not been experienced together. Importantly, a fish that was incorrect for one person was correct for another person, such that reinforcement histories were equal for all fish. Participants then learn that one of the people is also associated with a different fish (P1-F2). If indeed the overlap in the associations has led to a link between the two people, then this additional knowledge about one of the people may be expected to generalize to the other, creating a P2-F2 association. This generalization is assessed in the final Test Phase where participants are tested on all previously learned associations, as well as on the critical generalization probe, P2-F2.

Figure 1.

Sample task events and task structure for the learning and generalization paradigm. A single equivalence set is shown here. In the task, participants were trained simultaneously on two sets (4 people, 4 fish). A fish that was correct for one person, was incorrect for another person, so that the task could not be learned by simple stimulus-response associations.

The Learning phase was distributed gradually over three stages in a ‘shaping’ procedure, as shown in Figure 1 (see also Supplement 1). Upon completion of the third stage, an instruction screen appeared informing the participant that in the final part of the task no corrective feedback would be given, and that they would need to remember what they had learned previously. During the Test phase, participants were presented with interleaved trials consisting of the previously learned associations (‘trained’) and also the critical trials that probed for generalization to untrained associations. Additional details appear in Supplement 1.

RESULTS

Among the schizophrenia participants, there were two (one off and one on medication) who made more than 200 errors during the very first stage of learning (greater than 3 SDs from the mean of the group). These outliers were removed from all further analyses.

Learning

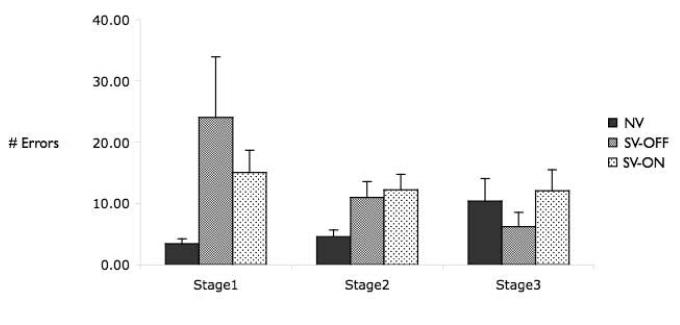

Figure 2 shows performance of all remaining subjects across the three stages of the Learning phase. A repeated-measures ANOVA with number of errors as the dependent variable, and learning stage (1-3) and group (NV, SV-OFF, SV-ON) as independent variables, revealed a trend for a difference in learning between the groups (F(2,71)=2.56, p=0.08), no difference across the learning stages (F(2,142)=1.55, p=0.21), and a trend for a group × stage interaction (F(4,142)=2.17, p=0.08). To further examine differences between the groups, we conducted a more liberal test using a separate ANOVA for each learning stage. This revealed a significant difference between the groups only during the first stage of learning (F(2,71)=3.35, p=0.04), reflecting significantly better performance among the NV than among either of the schizophrenia groups (NV vs. SV-ON, t(57)=2.27, p<0.05; NV vs. SV-OFF, t(33)=2.23, p<0.05), while the SV-ON and the SV-OFF did not differ (t(52)=1.07, p=0.29). By contrast, the effect of group was not significant during either the second (F(2,71)=2.44,p=0.94) or third (F(2,71)=0.56,p=0.57) stage of learning, revealing that the groups had reached a comparable level of learning prior to test. Note that the NV showed a trend (t(19)=1.8; p=0.08) towards an increase in number of errors between the second and third learning phase. The different phases of learning differ in the extent to which they test learning for each of the three different trial types (P1-F1; P2-F1; P1-F2, respectively). Thus, this trend is likely due to the increased memory load and increased conflict in the third stage, where subjects must learn a new outcome for an already well-learned stimulus.

Figure 2.

Learning performance across the three shaping stages for healthy controls (NV), individuals with schizophrenia tested off medication (SV-OFF), and individuals with schizophrenia tested on medication (SV-ON). Both patient groups made more errors in the very first learning stage; however, after this initial phase, the groups did not differ in their ability to learn the associations.

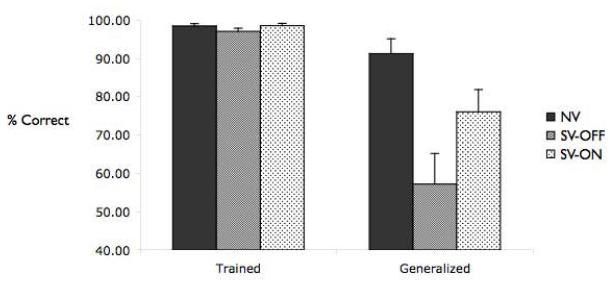

Test

Figure 3 shows performance of the three groups during the Test phase. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of group (F(1,71)=5.53, p<0.01), a main effect of trial type (‘generalized’ vs. ‘trained’; F(1,71)=36.15, p<0.001), and a group × trial type interaction (F(2,71)=4.676, p<0.01). Post hoc analyses indicated that the interaction was due to significantly worse generalization among the SV-OFF relative to the NV (p<0.01), while the groups did not differ on the ‘trained’ trials (all p>0.30). No differences were found between the SV-ON and NV on either ‘trained’ or ‘generalized’ trials (all Ps>0.15). Consistent with these results, one-sample t-tests confirmed that generalization performance was significantly above chance for both the NV and SV-ON groups (NV, t(19)=10.47, p<0.001; SV-ON, t(38)=4.35, p<0.001), but not for the SV-OFF group (t<1.0).

Figure 3.

Test phase performance for healthy controls (NV), individuals with schizophrenia tested off medication (SV-OFF), and individuals with schizophrenia tested on medication (SV-ON). All groups performed very well on the test of previously trained associations. However, the groups did differed in their ability to generalize what they learned: Schizophrenics off medication did not generalize what they learned; by contrast, schizophrenics tested on medication generalized well, and did not differ significantly from healthy controls.

Relation between Learning and Generalization

We found no significant relationship between learning rate (number of errors during the Learning phase) and generalization performance. This was the case for all three of the learning stages, and when we examined this relationship across all participants (Stage 1: r=0.13; Stage 2: r=0.08; Stage 3: r=0.17; all Ps>0.20) and for each group separately (NV, Stage 1: r=0.36; Stage 2: r=0.03; Stage 3: r=0.18; SV-OFF, Stage 1: r=0.13; Stage2: r=0.15; Stage 3: r=0.09; SV-ON, Stage1: r=0.10; Stage2: r=0.005; Stage 3: r=0.20; all Ps>0.13).

Relation between Medication Dose and Performance

We examined the relation between medication dose and performance for individuals in the SV-ON group. Dose was calculated according to two different methods (as described in [28] and [29]). We found no correlation between dose of medication and performance on either the Learning or the Test phase, for either calculation (Learning, Stage 1: r=0.10; Stage 2: r=0.16; Stage 3: r=0.22; Test, trained: r=0.01; generalized; r=0.13; all Ps>0.16).

Relation of Performance to Demographic & Neuropsychological Measures

We examined the relation between task performance and all demographic and neuropsychological measures.

Learning

Across all subjects, the number of errors during the first stage of learning was correlated with education (r=0.33), WTAR-IQ (r=0.41), and SFSTOT (r=0.41) (Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons; all Ps<0.01). Performance during the second and third stages of learning was not correlated with any demographic measures (all rs<0.20, all Ps>0.13).

A separate examination of neuropsychological measures among the patient groups revealed that performance on the first and second stage of learning correlated with RBANS total scores (Stage1: r=0.46; Stage2: r=0.51; Ps<0.005) and with RBANS delayed memory scores (Stage1: r=0.45; Stage2: r=0.55; Ps<0.005). No other measures correlated with learning (all rs<0.35, non-significant when corrected for multiple comparisons).

Test

Across all subjects, performance during Test (trained and generalization trials) was not correlated with any demographic measures (all rs<0.20). Given the difference in education levels between the SV-OFF and the NV groups, it is especially important to note that education and generalization were not even weakly correlated (r=0.08; p=0.47).

To further verify that differences in education between SV-OFF and SV-ON do not account for the differences in generalization performance, we conducted a separate analysis of Learning and Test phase performance while equating for education levels in the groups. To this end, we excluded those subjects from the SV-ON and NV groups who had the highest level of education (≥16 yrs), resulting in two new subgroups that did not differ in education from the SV-OFF group (SV-ON: n=28, mean yrs education=12.36, SD=1.73; NV: n=13, mean yrs education=12.9, SD=1.32; SV-OFF vs. SV-ON, p=0.20; SV-OFF vs. NV, p=0.49).

Analyses of task performance among these education-matched groups replicated the findings described above. Specifically, the SV-OFF did not differ from either the SV-ON or the NV in performance on the trained trials (p>0.40). Critically, however, the SV-OFF demonstrated significantly lower generalization performance compared to the NV (p<0.005) and the SV-ON (p<0.05).

We also examined the group differences found during Stage 1 of learning among these education-matched groups. This analysis revealed that among the education-matched groups, there was no significant differences in errors during Stage 1 of learning F(2,53)=2.25′ p=0.12).

Finally, when separately examining the neuropsychological measures limited to the education-matched patient groups, performance on the trained trials was correlated with the RBANS-TOT scores (r=0.44; p<0.005), but not with any other measures. Generalization performance was not significantly correlated with any neuropsychological measure, when correcting for multiple comparisons. Using a more liberal, uncorrected threshold, the only measure that showed a relationship with generalization performance was the RBANS-LANG (r=0.31; p<0.05; all other measures, Ps>0.40).

DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine the effect of schizophrenia and APDs on memory generalization. We found that individuals with schizophrenia are impaired at generalization, an impairment that was significant only among those schizophrenic volunteers who were tested off APDs. In contrast, schizophrenic individuals treated with APDs did not perform significantly worse than healthy controls. The effect of both disease and medication was selective to generalization: the on and off medication groups showed no impairments on retention of what they learned, and, importantly, both groups performed similarly during learning suggesting the lack of differences in retention is not easily explained by ceiling effects).

Memory Generalization in Schizophrenia

The paradigm used here has previously been shown to be sensitive and specific to hippocampal function [25-27]. The present findings thus complement previously reported data demonstrating impaired hippocampal-dependent generalization in schizophrenia [4, 30, 31], and extend these prior observations by demonstrating that generalization is sensitive to modulation by anti-psychotic medication. This raises important questions regarding the cause of generalization deficits in schizophrenia, as well as the mechanism by which anti-psychotic medication may impact generalization. In particular, recent fMRI data in healthy individuals demonstrate that hippocampal-midbrain interactions contribute to generalization. Taken together with the present findings, this raises the intriguing possibility that there may be an intrinsic alteration in hippocampal function in schizophrenia which is remediated by APDs. This idea is also consistent with recent theories suggesting that disrupted hippocampal-midbrain function may be a key feature of schizophrenia [32]. It is currently unknown as to precisely what effect APDs have on hippocampal function. Future studies exploring the interaction between hippocampal and midbrain dopamine regions in schizophrenia and the impact of APDs on hippocampal function will provide leverage on these speculative possibilities.

Effect of APDs on Memory and the Hippocampus

It is a prevailing assumption that anti-psychotic medication does not have an action on any aspect of hippocampal-dependent memory in schizophrenia [33]. APDs reduce psychotic symptoms; however, reports regarding their effect on memory and other aspects of cognition have not been documented [34]. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that medication may positively impact generalization in a paradigm previously shown to depend on hippocampal function [25-27].

This key finding must be understood in light of both what is known about APD action in the medial temporal lobe. APDs block D2 receptors that are located anteriorly in hippocampus and in highest concentrations in DG, CA1 and subiculum. Additionally, APDs have been shown to alter LTP in hippocampal subfields, through D1 dopamine receptor actions [35, 36], modulating activity dependent plasticity [21]. Activity within the perforant pathway is modulated by dopamine, affecting the integration of perforant pathway and schafer collateral transmission into CA1 [37]. APDs may also have indirect effects on hippocampal transmission by altering activity within the cortical-subcortical long track pathways. Precisely what of the pharmacology of dopamine in hippocampus is involved in the actions we report here remains a speculation.

The present contrast between SV-ON and SV-OFF shows improved memory-based generalization in individuals tested on APDs, which has not been shown previously. Generalization performance was impaired in the SV-OFF group and was significantly better, though still not normal, in the SV-ON group. This latter observation supports a speculative therapeutic action of APDs on memory-based generalization in schizophrenia.

Selective Effects of Schizophrenia and APDs on Memory Generalization

The present findings indicate that APDs had a selective effect on the ability to generalize learned associations. By contrast, there were no differences between medication groups on feedback-based associative learning, nor on memory for previously learned associations. Thus, our data suggest that schizophrenia - and APDs -may selectively impact only particular aspects of memory function. The selectivity of this effect may have important implications for understanding the nature and cause of cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Additionally, the present data add to a growing number of studies suggesting that associative learning and generalization may tap into dissociable processes [25, 27, 38]. First, we found that medication selectively impacted generalization, but not learning. Second, we found that performance in the early stages of learning correlated with a number of demographic and neuropsychological measures, while generalization did not. This last finding is particularly interesting given that, among volunteers with schizophrenia, both the on and off medication subjects made more errors than healthy controls on the earliest learning stage. Taken together, these findings suggest that early learning in this task varies as based on IQ, age, education, and/or general attentional learning-set abilities – all abilities that do not appear to contribute directly to generalization processes.

In contrast to generalization, the learning phase of the paradigm used here has been shown to be sensitive to striatal function, both in fMRI and in patient studies [25, 27]. There has been one previous report that medication dose in schizophrenia correlated with number of errors in the learning phase of a task similar to the one used here [30]. However, we found neither an effect of medication on learning phase performance, nor a correlation with medication dose, consistent with a more recent report [31]. This difference may be related to the overall higher APD doses tested in that study [30], compared to the present one. Together with other converging evidence suggesting that learning-phase performance on this task depends on striatal mechanisms [6, 25, 39], these results suggest that learning-phase performance on this task may be impacted. Future studies are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of how medication dose may differentially impact different aspects of memory function.

Limitations and Future Directions

A potential limitation in interpreting the present findings is that the on vs. off medication effects were compared between individuals. Because cognitive tasks (particularly learning and memory tasks) are sensitive to learning-set effects, between-subjects designs, as used here, are best suited for this kind of study. However, this design necessitates a consideration of possible differences between the groups other than medication status. In particular, it is important to consider that the groups may differ not only in treatment, but in disease state, as well. Nonetheless, there are several indications that the effects we found are not due to global differences between the groups. First, the effects are selective to generalization, rather than global cognitive differences. Second, the difference between the groups does not appear to be related to any other demographic or neuropsychological measure. Although the off medication group had on average lower education levels, this does not appear to relate to differences in generalization. Over all participants, education did not correlate with generalization performance. This does not appear to be due to lack of sensitivity in the education measure, since education did correlate with number of errors in the first learning stage. Furthermore, the difference in education levels between the groups was driven primarily by a number of high-education subjects in the on medication and the control groups. When removing these high-education subjects from the analyses, the effects of medication on generalization performance remain significant.

Conclusions

Although schizophrenia is a complex multi-faceted disorder, the present findings show that cognitive dysfunctions in memory are selective, not global. Therefore, schizophrenia can provide a relatively selective model for certain aspects of cognitive disruption. In particular, the disease and its treatment with APDs may be specifically vulnerable to memory processes that depend on the hippocampus, and which may be impacted by dopamine modulation. Taken together with recent functional imaging data, the current results suggest that the hippocampus may be powerfully modulated by dopaminergic mechanisms (either through a direct effect, a systems action, or both) which enable the acquisition of associative memories that support later generalization across experiences, functions that are impaired in schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, National Institute of Mental Health (5R01–MH080309 to A.D.W.; 1 R34 MH075863, SMRI 05-RC-001 to C.T., and 5F32MH072135 to D.S). The authors are grateful to R. Alison Adcock and Ed Smith for insightful discussion.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ongur D, et al. The neural basis of relational memory deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):356–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Titone D, et al. Transitive inference in schizophrenia: impairments in relational memory organization. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):235–47. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00152-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aleman A, et al. Memory impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1358–66. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heckers S, et al. Hippocampal activation during transitive inference in humans. Hippocampus. 2004;14(2):153–62. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preston AR, et al. Hippocampal contribution to the novel use of relational information in declarative memory. Hippocampus. 2004;14(2):148–52. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shohamy D, Wagner AD. Integrating memories in the human brain: hippocampal-midbrain encoding of overlapping events. Neuron. 2008;60(2):378–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol Rev. 1992;99(2):195–231. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabrieli JD. Cognitive neuroscience of human memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichenbaum HE, Cohen NJ. From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honea R, et al. Regional deficits in brain volume in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2233–45. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steen RG, et al. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malaspina D, et al. Resting neural activity distinguishes subgroups of schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(12):931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamminga CA, et al. Limbic system abnormalities identified in schizophrenia using positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose and neocortical alterations with deficit syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(7):522–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820070016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyler Zorrilla LT, et al. Functional abnormalities of medial temporal cortex during novel picture learning among patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;59(2-3):187–98. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jessen F, et al. Reduced hippocampal activation during encoding and recognition of words in schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1305–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heckers S. Neuroimaging studies of the hippocampus in schizophrenia. Hippocampus. 2001;11(5):520–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaral DG, Cowan WM. Subcortical afferents to the hippocampal formation in the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1980;189(4):573–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.901890402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasbarri A, et al. Anterograde and retrograde tracing of projections from the ventral tegmental area to the hippocampal formation in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33(4):445–52. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson LW. The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: a combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9(1-6):321–53. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey U, Schroeder H, Matthies H. Dopaminergic antagonists prevent long-term maintenance of posttetanic LTP in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1990;522(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otmakhova NA, Lisman JE. D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation increases the magnitude of early long-term potentiation at CA1 hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 1996;16(23):7478–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07478.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlsson A, Lindqvist M. Effect Of Chlorpromazine Or Haloperidol On Formation Of 3methoxytyramine And Normetanephrine In Mouse Brain. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1963;20:140–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1963.tb01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis JM, Klein DF, Davis JM, editors. Diagnosis and Drug Treament of Psychiatric Disorders. The Williams and Wilkins Company; Baltimore: 1969. Review of antipsychotic drug literature; pp. 52–138. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):553–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers CE, et al. Dissociating hippocampal versus basal ganglia contributions to learning and transfer. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15(2):185–93. doi: 10.1162/089892903321208123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collie A, et al. Selectively impaired associative learning in older people with cognitive decline. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(3):484–92. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shohamy D, Wagner AD. Building integrated memories in the human brain: Hippocampal-midbrain encoding of overlapping events. Neuron. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association AP. Treatment of patients with schizophrenia: Practice guidelines for the treatment pf psychiatric disorders. APA; Washington: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rey MJ, et al. Guidelines for the dosage of neuroleptics. I: Chlorpromazine equivalents of orally administered neuroleptics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989;4(2):95–104. doi: 10.1097/00004850-198904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keri S, et al. Dissociation between medial temporal lobe and basal ganglia memory systems in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(2-3):321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farkas M, et al. Associative learning in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 2008;19(1):55–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f2dff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lisman JE, et al. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(5):234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Effects of neuroleptic medications on the cognition of patients with schizophrenia: a review of recent studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 9):62–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geyer MA, Tamminga C. MATRICS: Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174(Special Issue):1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumoto M, et al. Characterization of clozapine-induced changes in synaptic plasticity in the hippocampal-mPFC pathway of anesthetized rats. Brain Res. 2008;1195:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navakkode S, Sajikumar S, Frey JU. Synergistic requirements for the induction of dopaminergic D1/D5-receptor-mediated LTP in hippocampal slices of rat CA1 in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52(7):1547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otmakhova NA, Lisman JE. Dopamine selectively inhibits the direct cortical pathway to the CA1 hippocampal region. J Neurosci. 1999;19(4):1437–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01437.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shohamy D, et al. L-dopa impairs learning, but spares generalization, in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(5):774–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shohamy D, et al. Basal ganglia and dopamine contributions to probabilistic category learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(2):219–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.