Abstract

The use of trimethoprim in treatment of Streptococcus pyogenes infections has long been discouraged because it has been widely believed that this pathogen is resistant to this antibiotic. To gain more insight into the extent and molecular basis of trimethoprim resistance in S. pyogenes, we tested isolates from India and Germany and sought the factors that conferred the resistance. Resistant isolates were identified in tests for trimethoprim or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) susceptibility. Resistant isolates were screened for the known horizontally transferable trimethoprim-insensitive dihydrofolate reductase (dfr) genes dfrG, dfrF, dfrA, dfrD, and dfrK. The nucleotide sequence of the intrinsic dfr gene was determined for resistant isolates lacking the horizontally transferable genes. Based on tentative criteria, 69 out of 268 isolates (25.7%) from India were resistant to trimethoprim. Occurring in 42 of the 69 resistant isolates (60.9%), dfrF appeared more frequently than dfrG (23 isolates; 33.3%) in India. The dfrF gene was also present in a collection of SXT-resistant isolates from Germany, in which it was the only detected trimethoprim resistance factor. The dfrF gene caused resistance in 4 out of 5 trimethoprim-resistant isolates from the German collection. An amino acid substitution in the intrinsic dihydrofolate reductase known from trimethoprim-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae conferred resistance to S. pyogenes isolates of emm type 102.2, which lacked other aforementioned dfr genes. Trimethoprim may be more useful in treatment of S. pyogenes infections than previously thought. However, the factors described herein may lead to the rapid development and spread of resistance of S. pyogenes to this antibiotic agent.

INTRODUCTION

Trimethoprim is used for the treatment of enteric, respiratory, skin, and urinary tract infections (1). It acts bacteriostatically by inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), an enzyme of the folate synthesis pathway. Interference with this pathway inhibits bacterial DNA synthesis (2). Typically, trimethoprim is used in combination with sulfamethoxazole, a sulfonamide. This combination is also known as co-trimoxazole or SXT. Like other sulfonamides, sulfamethoxazole is an inhibitor of the dihydropteroate synthase, another enzyme of the folate synthesis pathway (3–5). Because of early nonstandardized antibiotic susceptibility tests, Streptococcus pyogenes has been considered largely resistant to SXT. S. pyogenes is pathogenic in humans, causing a variety of diseases. This spectrum of diseases ranges from pharyngitis, tonsillitis, and suppurative skin and soft tissue infections to severe invasive infections and immune sequelae (6, 7).

Today's knowledge of the pitfalls in SXT susceptibility testing has raised doubts about some of the early data and the widespread resistance of S. pyogenes to this combination drug (8). SXT may be an underestimated alternative to other antibiotics under certain circumstances, such as in the treatment of streptococcal skin and soft tissue coinfections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (8, 9). However, a reevaluation of SXT for use in S. pyogenes infections requires clinical studies and more, reliable data on the spread of resistance. Knowledge about the genes and mutations that confer resistance to S. pyogenes against sulfur antibiotics or trimethoprim is scant but is a prerequisite for a comprehensive understanding of the extent of resistance and its development. Studies by Swedberg et al. (4) and Jönsson et al. (3) identified mutations in the chromosomally encoded dihydropteroate synthase as a cause for sulfonamide resistance in S. pyogenes. In our previous work, we report trimethoprim resistance in S. pyogenes due to the dihydrofolate reductase (dfr) gene dfrG (10). To our knowledge, no other mutations and genes that confer resistance to trimethoprim or sulfonamides to S. pyogenes have been reported.

Generally, bacterial resistance to trimethoprim is mediated by the following five main mechanisms: (i) a permeability barrier (1, 11), (ii) a naturally insensitive intrinsic DHFR (1), (iii) spontaneous mutations in the intrinsic DHFR (12–17), (iv) increased production of the sensitive target enzyme by upregulation of gene expression or gene duplication (18), and (v) horizontal acquisition (plasmid mediated or conjugation) of dfr genes that encode resistant DHFRs. Only a few horizontally transmissible dfr genes have been identified so far in Gram-positive bacteria (Table 1). Only one of them, the dfrG gene, has been detected in S. pyogenes.

TABLE 1.

Horizontally transmissible dfr genes in Gram-positive bacteria

| Resistance gene | Species | Reference or GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| dfrA | Staphylococcus aureus | 33 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 34 | |

| dfrD | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 34 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 35 | |

| dfrK | Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | 36 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 37 | |

| Staphylococcus hyicus | 38 | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 38 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 32 | |

| Enterococcus durans, Enterococcus hirae | 32 | |

| Enterococcus gallinarum, Enterococcus casseliflavus | 32 | |

| dfrF | Various enterococcal species | 32 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 31 | |

| dfrG | Enterococcus faecium | 39 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 40 | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | GenBank accession no. FM204877.1 | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 30 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 10 |

Although penicillin has been used against S. pyogenes for a long time, in vitro resistance against this antibiotic has not yet been observed for this streptococcal species. However, treatment failure (19, 20) or adverse reactions to penicillin (21) may occur. Therefore, the development and spread of resistance of S. pyogenes to alternative antibiotics, such as erythromycin or clindamycin, is a matter of concern. The use of SXT for treatment of skin infections has been suggested for use in certain settings (8). Trimethoprim is among the most frequently used antimicrobial agents (22, 23) and is commonly prescribed in rural areas of India (24), where high resistance rates to SXT have been reported (25, 26). This required further examination, including investigations of the mechanisms that render S. pyogenes resistant to trimethoprim.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Indian S. pyogenes isolates were collected during a school survey and from clinical cases of human infection at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh (northern India), and the Christian Medical College, Vellore (southern India) (27, 28). S. pyogenes isolates from Germany were collected at the German National Reference Center for Streptococci. For details about the isolates from Germany and India, see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of S. pyogenes.

Data from routine tests of SXT susceptibility of 2,371 S. pyogenes isolates collected in Germany were analyzed at the German National Reference Center for Streptococci. The MICs for SXT were determined using the broth microdilution method as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (http://www.clsi.org). The microtiter plates (Sensititre NLMMCS10; TREK Diagnostic Systems Ltd., East Grinstead, United Kingdom) contained trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) in the ratio 1:19 (the concentrations [trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole], in mg/liter, were 0.25/4.75, 0.5/9.5, 1/19, 2/38, 4/76, and 8/152) with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) and 5% lysed horse blood. The final inoculum was 5 × 105 CFU/ml. Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 24 h in ambient air. Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used as a control strain. Isolates with a MIC of ≥2/38 mg/liter of SXT were sent to the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI).

Susceptibility to trimethoprim alone was tested at the HZI by using the following method of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST; http://www.eucast.org). MICs of trimethoprim were determined using the agar dilution method with a 2-fold dilution series from 512 mg/liter to 1 mg/liter of the antibiotic agent. Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood and 20 mg/liter β-NAD was used. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of trimethoprim that inhibited visible growth after 18 h of incubation at 37°C. Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 were used as quality control strains. Official breakpoints for resistance classification of S. pyogenes to trimethoprim were not available. Therefore, the isolates were classified tentatively as susceptible (MIC, ≤2 mg/liter), intermediate (MIC, 4 mg/liter), or resistant (MIC, >4 mg/liter) (see Discussion). Our tentative classification was based on official breakpoints of the EUCAST for resistance of S. pyogenes to SXT (susceptible, ≤1/19 mg/liter; resistant, >2/38 mg/liter) and for Streptococcus agalactiae to trimethoprim alone (susceptible, ≤2 mg/liter; resistant, >2 mg/liter).

DNA extraction and emm typing.

Genomic DNA was isolated with a Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) after bacterial lysis with zirconia beads. The highly variable 5′-terminal nucleotide sequence of the emm gene allows genotyping of S. pyogenes isolates. emm types were determined by amplification and sequencing of the 5′-end region of the emm gene using the primers emm_fwd (forward) and emm_rev (reverse) (Table 2). The nucleotide sequences were compared against the emm gene database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/strepblast.htm).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Annealing temp (°C) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dfrG_fwd | ATGAAAGTTTCTTTGATTGCTGCGA | 500 | 55 | 10 |

| dfrG_rev | CAATAAGTTTTTTCTTTCATATACATG | |||

| element_fwd | TTACAGGGTCTGCGGCTATT | 3,800/500a | 55 | 10 |

| element_rev | TTCAAAGCCGTCTCAGTCAC | |||

| dfrA_fwd | ATCAATAATTGTCGCTCACG | 405 | 52 | 41 |

| dfrA_rev | ACTGAAGATTCGACTTCCC | |||

| dfrD_fwd | GCAAGGATAACGACATTCC | 202 | 52 | 41 |

| dfrD_rev | GCAGCTTCTATTGAATGGG | |||

| dfrF_fwd | TTAACAACGGGTAATGTGGT | 201 | 52 | 41 |

| dfrF_rev | AAATAGTCCATATCCACCAG | |||

| dfrK_fwd | GAGAATCCCAGAGGATTGGG | 422 | 55 | 32 |

| dfrK_rev | CAAGAAGCTTTTCGCTCATAAA | |||

| dfr_fwd | GTTGCACTTTGACCTTGCTATTTAA | 646 | 55 | This study |

| dfr_rev | ATACTCCAAAAATACTACGTTGCAT | |||

| emm_fwd | TATTCGCTTAGAAAATTAA | 1,500 | 52 | 29 |

| emm_rev | GCAAGTTCTTCAGCTTGTTT |

The two amplicon sizes refer to amplicons with and without dfrG-carrying sequences, respectively.

Standard PCR.

PCR was performed using 0.2 μM suitable primers (Table 2), 0.2 mM (each) dNTP, 1× Crimson Taq PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.625 units of Crimson Taq DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs), with the addition of water to a final volume of 25 μl. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at gene-specific temperatures (Table 2) for 30 s, and extension at 68°C for 1 min per kb of gene length. The cycle reaction was followed by a final extension phase at 68°C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

PCR detection of the dfrG insertion sequence.

Isolates that were positive for the dfrG resistance gene were analyzed for the presence of the dfrG gene-carrying insertion element with primers element_fwd and element_rev (Table 2) specific for conserved regions that flank the integration site at genes that are homologous to SPy_1769 of S. pyogenes SF370. This strain bore no integration element (negative control) and therefore produced a 500-bp PCR product. Based on our 2012 publication (10), a 3.8-kb amplification product was expected for dfrG-positive isolates.

Recombinant overexpression of the S. pyogenes intrinsic dihydrofolate reductase gene dfr and determination of the MIC of overexpressing E. coli.

Intrinsic dfr genes of S. pyogenes isolates A981, A951, MGAS315, and SF370 were recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli TOP10. To this end, the dfr genes were amplified using primers dfr_fwd and dfr_rev (Table 2). The amplification products were ligated into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). After transformation of E. coli TOP10 with the vector, the bacteria were grown on Luria-Bertani agar containing 100 mg/liter ampicillin for selection of positive clones. Nucleotide sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The MICs of the E. coli clones were determined after cultivation on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with trimethoprim in a 2-fold dilution series.

Nucleotide sequence of intrinsic dfr genes and cluster analysis.

Intrinsic dfr genes were sequenced and novel sequence information was deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: A1359_dfr, KF737388; A981_dfr, KF737389; A1357_dfr, KF737390; A842_dfr, KF737391; A899_dfr, KF737392. Cluster analysis was carried out with ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) using the neighbor joining algorithm.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of isolates from India.

A total of 268 S. pyogenes isolates that comprised 72 different emm types was collected in India (27, 28). The emm type serves as a genotype marker for S. pyogenes (29). All isolates in the collection were examined for susceptibility to trimethoprim. In the agar dilution test, 73 S. pyogenes isolates (27.2%) were intermediate (MIC, 4 mg/liter) or resistant (MIC, >4 mg/liter) to trimethoprim. Of these 73 isolates, 65 resistant isolates showed MIC values above 16 mg/liter. Four resistant isolates showed MIC values of 8 to 16 mg/liter. The remaining 4 isolates that were classified as intermediate had MICs of 4 mg/liter (Table 3) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, 25.7% of the 268 S. pyogenes isolates from India were resistant to trimethoprim (n = 69) and 1.5% intermediate (n = 4).

TABLE 3.

Trimethoprim susceptibility and resistance factors in S. pyogenes isolates from India

| Region | No. (%) of isolates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Resistance factor detectedd |

Resistant (MIC > 4 mg/liter) | Intermediate (MIC = 4 mg/liter) | Susceptible (MIC < 4 mg/liter) | ||

| dfrG | dfrFa | |||||

| India | 268 (100) | 23 (8.6) | 46b (17.2) | 69 (25.7) | 4 (1.5) | 195 (72.8) |

| Northern India | 89 (100) | 21 (23.6) | 31c (34.8) | 49 (55.1) | 1 (1.1) | 39 (43.8) |

| Southern India | 179 (100) | 2 (1.1) | 15 (8.4) | 20 (11.2) | 3 (1.7) | 156 (87.1) |

Not all isolates that tested positive for the dfrF resistance gene were resistant to trimethoprim (see footnotes b and c).

Forty-two out of 46 isolates were resistant, 1 isolate was intermediate, and 3 isolates were susceptible.

Twenty-seven out of 31 isolates were resistant, 1 isolate was intermediate, and 3 isolates were susceptible.

Isolates were not tested for the resistance genes dfrA, dfrD, and dfrK.

Acquired trimethoprim resistance genes in S. pyogenes.

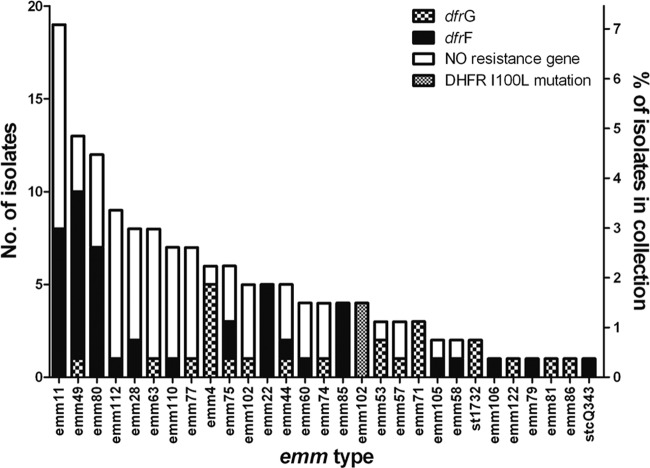

Recently, we reported the presence of a trimethoprim resistance determinant, the dfrG gene, in S. pyogenes emm type 1-2 (emm1-2) from India. The dfrG gene was located chromosomally within an insertion sequence of about 3.3 kb (10). To determine the distribution of the dfrG gene in S. pyogenes in India, all 268 isolates collected in India were tested by PCR. Of these isolates, 23 (8.6%) were positive for dfrG (Fig. 1; Table 3), all of them resistant and highly tolerant to trimethoprim (MIC, ≥256 mg/liter). The previously characterized 3.3-kb insertion element that contained the dfrG gene was integrated into a gene that was homologous to SPy_1769 of S. pyogenes SF370 (integration site). As shown by PCR, the insertion element that contained the dfrG gene was located in this integration site in 21 out of the 23 dfrG-positive isolates. The integration site of the two remaining isolates was not determined. As the majority of the intermediate or resistant isolates was negative for dfrG (50 out of 73), these isolates were examined by PCR for the presence of the trimethoprim resistance gene dfrF. This PCR analysis identified dfrF as a second acquired resistance gene in S. pyogenes. The dfrF gene was detected in 46 of the 268 isolates (17.2%) of the Indian collection (Table 3; Fig. 1). None of the isolates contained both dfrG and dfrF genes. Forty-two out of the 46 dfrF-positive isolates were classified as resistant to trimethoprim by antimicrobial susceptibility testing, with MICs equal to or higher than 32 mg/liter. Three of the dfrF-positive isolates were susceptible, and one was intermediate. None of the known trimethoprim resistance genes (dfrG, dfrF, dfrA, dfrD, and dfrK) was detected in the seven remaining intermediate or resistant isolates. Four out of these seven isolates without a known resistance factor belonged to emm type 102.2 and were classified as resistant (MIC range, 8 to 16 mg/liter). One S. pyogenes isolate of emm type 15.2 and two isolates of emm type 80.0 were intermediate (MIC, 4 mg/liter).

FIG 1.

Distribution of the acquired resistant dihydrofolate reductase genes dfrG and dfrF and of an isoleucine-to-leucine substitution at position 100 of the intrinsic DHFR (I→L) in Indian S. pyogenes isolates of different emm types (x axis).

Trimethoprim resistance in SXT-resistant S. pyogenes isolates from Germany.

Resistance to SXT was observed for 37 out of 2,371 isolates from Germany (1.6%). These 37 isolates were tested for susceptibility to trimethoprim alone. Due to this preselection for SXT resistance prior to trimethoprim susceptibility testing, a trimethoprim resistance rate for the complete collection of 2,371 isolates from Germany could not be determined. Four out of the 37 SXT-resistant isolates were resistant to trimethoprim (MIC, >512 mg/liter) and positive for the resistance gene dfrF (Table 4). Two of these isolates were of emm type 81, and the others were of emm type 28 and st 854, respectively. One trimethoprim-resistant isolate with a MIC of 8 mg/liter and 12 intermediate isolates (MIC, 4 mg/liter) were negative for dfrF (Table 4). The resistance genes dfrG, dfrA, dfrK, and dfrD were not detected in any of the 37 SXT-resistant isolates from Germany.

TABLE 4.

Trimethoprim susceptibility and trimethoprim resistance factors in SXT-resistant S. pyogenes isolates from Germany

| No. (%) of isolates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Resistance factor detecteda |

Resistant (MIC > 4 mg/liter) | Intermediate (MIC = 4 mg/liter) | Susceptible (MIC < 4 mg/liter) | |

| dfrG | dfrF | ||||

| 37 (100) | 0 | 4 (10.8) | 5b (13.5) | 12 (32.4) | 20 (54.1) |

All isolates tested were negative for the resistance genes dfrA, dfrD, and dfrK.

Four out of 5 resistant isolates were positive for the dfrF resistance gene. For one isolate, none of the known resistance factors was detected.

A point mutation in the intrinsic dihydrofolate reductase confers trimethoprim resistance to S. pyogenes.

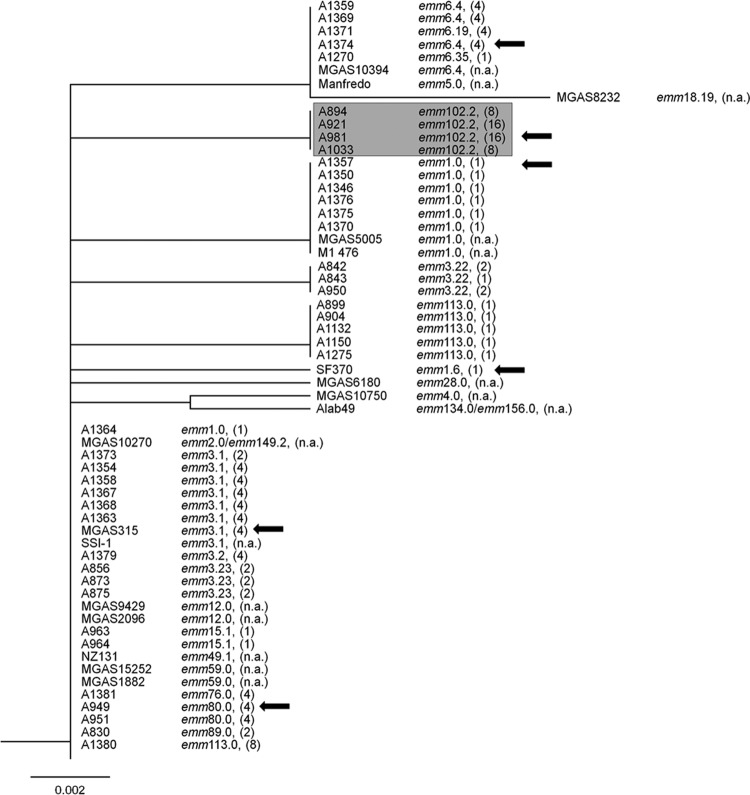

A total of 20 isolates from India and Germany were intermediate or resistant to trimethoprim despite lacking an acquired dfr gene. Therefore, intrinsic dfr genes of representative isolates were examined by DNA sequencing for mutations and differences in the encoded DHFR. The cluster dendrogram based on the amino acid sequences of the intrinsic DHFRs (Fig. 2) includes sequences of S. pyogenes isolates for which whole-genome sequences were available in the GenBank database. Despite belonging to different emm types, 27 of the 59 analyzed DHFR sequences were identical and formed one major cluster. The DHFRs of four emm102.2 streptococci formed a distinct cluster. The respective isolates were all collected in India and resistant to trimethoprim (MICs, 8 to 16 mg/liter). Compared to DHFRs of susceptible and intermediate isolates, the DHFR of the resistant emm102.2 isolates harbored an amino acid substitution of leucine for the isoleucine at position 100 (Fig. 3). The same substitution in the intrinsic DHFR was shown to be essential for trimethoprim resistance in S. pneumoniae (12, 17).

FIG 2.

Cluster dendrogram of amino acid sequences of intrinsic dihydrofolate reductases of selected Indian and German S. pyogenes isolates and from S. pyogenes whole-genome sequences, available in GenBank. emm types and MIC values (in mg/liter) are indicated to the right of the isolate designation. DFHRs of emm102.2 isolates with an isoleucine-to-leucine substitution at position 100 of the amino acid sequence form a distinct clade that is highlighted in gray. Arrows indicate the DHRFs that are shown in Fig. 3 and those overexpressed in E. coli (Fig. 4.). n.a., not available.

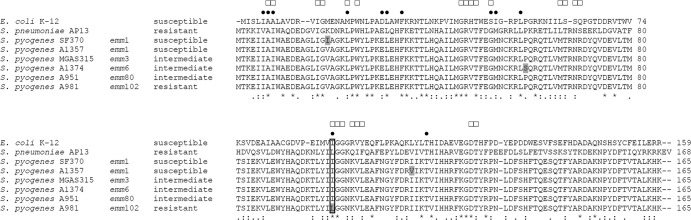

FIG 3.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of the intrinsic DHFR of trimethoprim-susceptible E. coli K-12, trimethoprim-susceptible S. pyogenes SF370 and A1357, trimethoprim-intermediate S. pyogenes MGAS315, A1374, and A951, and trimethoprim-resistant S. pyogenes A981 and S. pneumoniae AP13 (12). Isolate designations, emm types of S. pyogenes isolates, and resistance classifications are given on the left. Indicated are amino acid positions involved in trimethoprim (●) and NADPH cofactor (□) binding of the E. coli K-12 enzyme (13–16). Differences between the S. pyogenes DHFRs are highlighted in gray. Identical amino acids (*), conserved substitutions (:), and semiconserved substitutions (.) are indicated as determined by multiple alignment of all sequences. Amino acid positions are indicated on the right. A box indicates position 100.

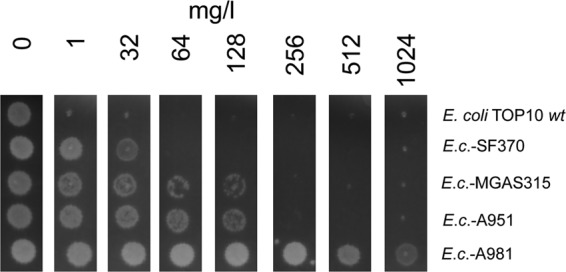

To examine if the mutation at position 100 of the DHFR renders S. pyogenes resistant to trimethoprim, the intrinsic dfr genes of the resistant isolate A981 (emm102.2; MIC, 16 mg/liter), of the intermediate isolates A951 (emm80; MIC, 4 mg/liter) and MGAS315 (emm3; MIC, 4 mg/liter), and of the susceptible isolate SF370 (emm1; MIC, 1 mg/liter) were recombinantly expressed in E. coli. The E. coli clones were designated E.c.-A981, E.c.-A951, E.c.-MGAS315, and E.c.-SF370, respectively. The DHFR of S. pyogenes SF370 differed from the DHFR of S. pyogenes MGAS315 and A951 by one amino acid, at position 19, at which DHFR of SF370 carried an isoleucine instead of a valine (Fig. 3). In the agar dilution test for trimethoprim resistance (Fig. 4), the wild-type E. coli isolate was susceptible (MIC, <1 mg/liter). In accord with the trimethoprim susceptibility test of the S. pyogenes isolates, E. coli clone E.c.-SF370, which produced a DHFR with an isoleucine at position 19, was the most susceptible one. Higher tolerance was observed with the two clones E.c.-A951 and E.c.-MGAS315, which produced a DHFR with valine at position 19. The highest tolerance to trimethoprim was observed with clone E.c.-A981. This clone produced a DHFR with a valine at position 19. Moreover, in contrast to the other DHFRs, it harbored the replacement of isoleucine with leucine at position 100. Taken together, the results indicate that a replacement of isoleucine with leucine at position 100 of the intrinsic DHFR caused trimethoprim resistance in S. pyogenes.

FIG 4.

Effect of trimethoprim on growth of E. coli TOP10 transformed with the intrinsic dfr genes of S. pyogenes strains SF370 and MGAS315 and of the Indian S. pyogenes isolates A951 and A981 (Fig. 2). The E. coli clones are referred to as E.c.-SF370, E.c.-MGAS315, E.c.-A951, and E.c.-A981, respectively. The MIC was determined on Mueller-Hinton agar with a 2-fold dilution series of trimethoprim. The clone designation is shown on the right. Formation of a bright colony on the dark agar indicates growth in the presence of trimethoprim in the concentration that is indicated above in mg/liter. The figure shows one representative experiment out of three.

DISCUSSION

Commonly, trimethoprim is used together with sulfamethoxazole as a component of the combination drug SXT. Official breakpoints for the classification of trimethoprim resistance of S. pyogenes are lacking. Therefore, we used tentative values (see Materials and Methods) that do not take into account clinical data and experiences with the treatment of S. pyogenes infections with trimethoprim. Notably, out of the 215 isolates that were classified as susceptible in our study, 128 and 87 had a MIC of ≤1 mg/liter and ≤2 mg/liter, respectively. Out of the 90 isolates that were not classified as susceptible, a considerable number, 16 isolates, showed a lower tolerance (MIC, 4 mg/liter) than that of the remaining 74 isolates (Tables 3 and 4) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Therefore, isolates with a MIC of 4 mg/liter were classified as intermediate and isolates with higher MICs (≥8 mg/liter) were classified as resistant.

Based on our classification, resistance to trimethoprim required the horizontal acquisition of dfr genes or an isoleucine-to-leucine substitution at position 100 of the intrinsic DHFR. For one resistant isolate, S. pyogenes A1308 from Germany (MIC, 8 mg/liter), no resistance factor was identified. Of the 74 resistant isolates from India and Germany, 23 harbored the dfrG resistance gene (MICs, 256 to >512 mg/liter), 46 isolates harbored the dfrF resistance gene (MICs, 32 to >512 mg/liter), and the aforementioned substitution in the intrinsic DHFR was detected in four isolates (MICs, 8 to 16 mg/liter). To our knowledge, this is the first description of the dfrF gene and of the amino acid substitution at position 100 in the intrinsic DHFR as trimethoprim resistance factors in S. pyogenes. Notably, not all of the isolates that carried the dfrF gene were resistant to trimethoprim. Three out of the 50 dfrF-positive isolates were susceptible to trimethoprim and one was intermediate, which could be due to low expression levels of this resistance gene. Still, dfrF was the most frequent factor in India that conferred trimethoprim resistance to the S. pyogenes isolates and was present in 15.6% of the isolates. The dfrF gene was present in isolates from Germany also, where it was the only trimethoprim resistance factor detected and caused resistance in 4 out of the 5 trimethoprim-resistant isolates (Table 4). The high rate of 25.7% isolates with trimethoprim resistance was observed in India; this may have been caused by frequent prescription of this drug in rural settings of India (24, 25). When considered separately, the resistance rate was higher in northern India (55.1%) than in southern India (11.2%) (Table 3). A resistance rate for Germany was not determined, as the isolates of this study were preselected for SXT resistance.

In a previous publication (10), we described a 3.3-kb DNA sequence that contained the dfrG gene and that was integrated into the genome of S. pyogenes emm1-2 isolates. The element was integrated into a sequence that was homologous to SPy_1769. Recently, Bertsch et al. (30) identified an identical 3.3-kb sequence, which was a part of the transposon Tn916 in Listeria monocytogenes. Other parts of the Tn916 transposon bore genetic elements for bacterial conjugation. Although a circular form of the 3.3-kb sequence was detected in L. monocytogenes, the dfrG-containing fragment could not be transferred on its own to L. monocytogenes or to Enterococcus faecalis (30). Transfer of the dfrG gene was observed only when it was part of Tn916, which provided genetic elements that were required for conjugation. Notably, we identified S. pyogenes isolates of 15 different emm types that harbored the 3.3-kb dfrG-containing sequence devoid of transposon sequences. In most of the isolates, the dfrG gene was integrated into the genome at the site mentioned above. The mode of transfer remains elusive.

In the present study, the dfrG gene was more frequently detected in southern India than in northern India. Two out of 179 isolates (1.1%) from southern India, both of emm type st1732.1, harbored dfrG. In contrast, 21 out of 89 isolates (23.6%) from northern India were positive for dfrG. These 21 isolates belonged to 14 different emm types, which excludes the possibility that all isolates were clonal and suggests that horizontal transfer of the dfrG gene occurs with considerable frequency. Like the dfrG gene, the dfrF gene was found in isolates of various emm types. Conversely, dfrF was more frequent in northern India, where it was detected in 31 isolates (34.8%) of 14 different emm types. In southern India, dfrF was detected in 15 isolates (8.4%) of 5 different emm types. The nature of the DNA element that carries the dfrF gene remains unknown. To date, the resistance gene dfrF has only been observed in different enterococcal species (31, 32). Our data suggest that it is transferable to S. pyogenes, although the mode of transfer remains unknown. Taken together, the data presented herein suggest a considerable horizontal transfer of dfrG and dfrF in S. pyogenes in India.

As reported previously, an amino acid substitution of isoleucine with leucine at position 100 of the intrinsic DHFR caused trimethoprim resistance in S. pneumoniae (12, 17). In our study, the same mutation conferred trimethoprim resistance to all 4 S. pyogenes isolates of emm type 102.2 that were isolated in India. The isolates differed in their MICs, which may be due to differences in biosynthesis of the enzyme (Fig. 2). Taking previous observations into account, one can conclude that a single mutation either in the intrinsic dihydrofolate reductase gene or in the dihydropteroate synthase gene (3, 4) is sufficient to diminish the susceptibility of S. pyogenes to trimethoprim or sulfonamides, respectively.

Recommendations against the use of SXT for S. pyogenes infections continue in the belief that the pathogen is intrinsically resistant to this drug. As discussed recently by Bowen et al., this seems to be a misconception. Studies reporting high resistance rates either used media known to have high concentrations of thymidine, which attenuates the antimicrobial effect of SXT, or did not provide details of the medium used. Today, Mueller-Hinton medium is used in trimethoprim and SXT susceptibility testing to ensure a low thymidine concentration (8). As suggested by others, SXT may be a valuable alternative for treatment of skin and soft tissue coinfections with S. pyogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, for which penicillin treatment is losing efficacy (8). The results of our study support the notion that the efficacy of trimethoprim for treatment of S. pyogenes infections in certain geographic regions is underestimated. However, we also identified factors that may readily cause resistance to trimethoprim in S. pyogenes and its rapid spread.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 February 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02282-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huovinen P, Sundstrom L, Swedberg G, Skold O. 1995. Trimethoprim and sulfonamide resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:279–289. 10.1128/AAC.39.2.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miovic M, Pizer LI. 1971. Effect of trimethoprim on macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 106:856–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jönsson M, Strom K, Swedberg G. 2003. Mutations and horizontal transmission have contributed to sulfonamide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:147–153. 10.1089/107662903765826732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swedberg G, Ringertz S, Skold O. 1998. Sulfonamide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes is associated with differences in the amino acid sequence of its chromosomal dihydropteroate synthase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1062–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushby SR. 1975. Synergy of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 112:63–66 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhatwal GS, Graham RM. 2008. Streptococcal diseases, p 231–241 In Encyclopedia of public health 2008. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nitsche-Schmitz DP, Chhatwal GS. 2013. Host-pathogen interactions in streptococcal immune sequelae. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 368:155–171. 10.1007/82_2012_296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen AC, Lilliebridge RA, Tong SY, Baird RW, Ward P, McDonald MI, Currie BJ, Carapetis JR. 2012. Is Streptococcus pyogenes resistant or susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole? J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:4067–4072. 10.1128/JCM.02195-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong SY, Andrews RM, Kearns T, Gundjirryirr R, McDonald MI, Currie BJ, Carapetis JR. 2010. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with benzathine penicillin for treatment of impetigo in Aboriginal children: a pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Paediatr. Child Health 46:131–133. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann R, Sagar V, Nitsche-Schmitz DP, Chhatwal GS. 2012. First detection of trimethoprim resistance determinant dfrG in Streptococcus pyogenes clinical isolates in India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5424–5425. 10.1128/AAC.01284-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huovinen P. 1987. Trimethoprim resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1451–1456. 10.1128/AAC.31.10.1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pikis A, Donkersloot JA, Rodriguez WJ, Keith JM. 1998. A conservative amino acid mutation in the chromosome-encoded dihydrofolate reductase confers trimethoprim resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 178:700–706. 10.1086/515371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolin JT, Filman DJ, Matthews DA, Hamlin RC, Kraut J. 1982. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus casei dihydrofolate reductase refined at 1.7 Å resolution. I. General features and binding of methotrexate. J. Biol. Chem. 257:13650–13662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filman DJ, Bolin JT, Matthews DA, Kraut J. 1982. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus casei dihydrofolate reductase refined at 1.7 Å resolution. II. Environment of bound NADPH and implications for catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 257:13663–13672 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews DA, Bolin JT, Burridge JM, Filman DJ, Volz KW, Kaufman BT, Beddell CR, Champness JN, Stammers DK, Kraut J. 1985. Refined crystal structures of Escherichia coli and chicken liver dihydrofolate reductase containing bound trimethoprim. J. Biol. Chem. 260:381–391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DA, Bolin JT, Burridge JM, Filman DJ, Volz KW, Kraut J. 1985. Dihydrofolate reductase. The stereochemistry of inhibitor selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 260:392–399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adrian PV, Klugman KP. 1997. Mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of trimethoprim-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2406–2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brochet M, Couve E, Zouine M, Poyart C, Glaser P. 2008. A naturally occurring gene amplification leading to sulfonamide and trimethoprim resistance in Streptococcus agalactiae. J. Bacteriol. 190:672–680. 10.1128/JB.01357-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook I. 2001. Failure of penicillin to eradicate group A beta-hemolytic streptococci tonsillitis: causes and management. J. Otolaryngol. 30:324–329. 10.2310/7070.2001.19359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Johnson DR. 2001. Unexplained reduced microbiological efficacy of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G and of oral penicillin V in eradication of group a streptococci from children with acute pharyngitis. Pediatrics 108:1180–1186. 10.1542/peds.108.5.1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macy E, Ngor E. 4 April 2013. Recommendations for the management of beta-lactam intolerance. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 10.1007/s12016-013-8369-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coenen S, Adriaenssens N, Versporten A, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, Vankerckhoven V, Aerts M, Hens N, Molenberghs G, Goossens H, ESAC Project Group 2011. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient use of tetracyclines, sulphonamides and trimethoprim, and other antibacterials in Europe (1997-2009). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66(Suppl 6):vi57–vi70. 10.1093/jac/dkr458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClean P, Hughes C, Tunney M, Goossens H, Jans B, European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Nursing Home Project G 2011. Antimicrobial prescribing in European nursing homes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1609–1616. 10.1093/jac/dkr183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bapna JS, Tekur U, Gitanjali B, Shashindran CH, Pradhan SC, Thulasimani M, Tomson G. 1992. Drug utilization at primary health care level in southern India. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 43:413–415. 10.1007/BF02220618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devi U, Borah PK, Mahanta J. 2011. The prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of beta-hemolytic streptococci colonizing the throats of schoolchildren in Assam, India. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 5:804–808. 10.3855/jidc.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A, Shukla VK, Tiwari V, Kumar R. 2008. Antibiotic resistance pattern of group-A beta-hemolytic streptococci isolated from north Indian children. Indian J. Med. Sci. 62:392–396. 10.4103/0019-5359.44018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagar V, Bergmann R, Nerlich A, McMillan DJ, Nitsche Schmitz DP, Chhatwal GS. 2012. Variability in the distribution of genes encoding virulence factors and putative extracellular proteins of Streptococcus pyogenes in India, a region with high streptococcal disease burden, and implication for development of a regional multisubunit vaccine. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19:1818–1825. 10.1128/CVI.00112-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haggar A, Nerlich A, Kumar R, Abraham VJ, Brahmadathan KN, Ray P, Dhanda V, Joshua JM, Mehra N, Bergmann R, Chhatwal GS, Norrby-Teglund A. 2012. Clinical and microbiologic characteristics of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infections in north and south India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:1626–1631. 10.1128/JCM.06697-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Facklam R, Beall B, Efstratiou A, Fischetti V, Johnson D, Kaplan E, Kriz P, Lovgren M, Martin D, Schwartz B, Totolian A, Bessen D, Hollingshead S, Rubin F, Scott J, Tyrrell G. 1999. emm typing and validation of provisional M types for group A streptococci. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:247–253. 10.3201/eid0502.990209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertsch D, Uruty A, Anderegg J, Lacroix C, Perreten V, Meile L. 2013. Tn6198, a novel transposon containing the trimethoprim resistance gene dfrG embedded into a Tn916 element in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:986–991. 10.1093/jac/dks531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coque TM, Singh KV, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 1999. Characterization of dihydrofolate reductase genes from trimethoprim-susceptible and trimethoprim-resistant strains of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:141–147. 10.1093/jac/43.1.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez M, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Torres C. 2012. First detection of the staphylococcal trimethoprim resistance gene dfrK and the dfrK-carrying transposon Tn559 in enterococci. Microb. Drug Resist. 18:13–18. 10.1089/mdr.2011.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouch DA, Messerotti LJ, Loo LS, Jackson CA, Skurray RA. 1989. Trimethoprim resistance transposon Tn4003 from Staphylococcus aureus encodes genes for a dihydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthetase flanked by three copies of IS257. Mol. Microbiol. 3:161–175. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb01805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dale GE, Langen H, Page MG, Then RL, Stuber D. 1995. Cloning and characterization of a novel, plasmid-encoded trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase from Staphylococcus haemolyticus MUR313. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1920–1924. 10.1128/AAC.39.9.1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charpentier E, Courvalin P. 1997. Emergence of the trimethoprim resistance gene dfrD in Listeria monocytogenes BM4293. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1134–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perreten V, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Gronlund Andersson U, Finn M, Greko C, Moodley A, Kania SA, Frank LA, Bemis DA, Franco A, Iurescia M, Battisti A, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, van Duijkeren E, Weese JS, Fitzgerald JR, Rossano A, Guardabassi L. 2010. Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Europe and North America: an international multicentre study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1145–1154. 10.1093/jac/dkq078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadlec K, Schwarz S. 2009. Identification of a novel trimethoprim resistance gene, dfrK, in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strain and its physical linkage to the tetracycline resistance gene tet(L). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:776–778. 10.1128/AAC.01128-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kadlec K, Fessler AT, Couto N, Pomba CF, Schwarz S. 2012. Unusual small plasmids carrying the novel resistance genes dfrK or apmA isolated from methicillin-resistant or -susceptible staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:2342–2345. 10.1093/jac/dks235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanimoto K, Ike Y. 2002. Analysis of the conjugal transfer system of the pheromone-independent highly transferable Enterococcus plasmid pMG1: identification of a tra gene (traA) up-regulated during conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 184:5800–5804. 10.1128/JB.184.20.5800-5804.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sekiguchi J, Tharavichitkul P, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Chupia V, Fujino T, Araake M, Irie A, Morita K, Kuratsuji T, Kirikae T. 2005. Cloning and characterization of a novel trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase from a nosocomial isolate of Staphylococcus aureus CM.S2 (IMCJ1454). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3948–3951. 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3948-3951.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cattoir V, Huynh TM, Bourdon N, Auzou M, Leclercq R. 2009. Trimethoprim resistance genes in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium clinical isolates from France. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:390–392. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.