Abstract

As a class, nucleotide inhibitors (NIs) of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase offer advantages over other direct-acting antivirals, including properties, such as pangenotype activity, a high barrier to resistance, and reduced potential for drug-drug interactions. We studied the in vitro pharmacology of a novel C-nucleoside adenosine analog monophosphate prodrug, GS-6620. It was found to be a potent and selective HCV inhibitor against HCV replicons of genotypes 1 to 6 and against an infectious genotype 2a virus (50% effective concentration [EC50], 0.048 to 0.68 μM). GS-6620 showed limited activities against other viruses, maintaining only some of its activity against the closely related bovine viral diarrhea virus (EC50, 1.5 μM). The active 5′-triphosphate metabolite of GS-6620 is a chain terminator of viral RNA synthesis and a competitive inhibitor of NS5B-catalyzed ATP incorporation, with Ki/Km values of 0.23 and 0.18 for HCV NS5B genotypes 1b and 2a, respectively. With its unique dual substitutions of 1′-CN and 2′-C-Me on the ribose ring, the active triphosphate metabolite was found to have enhanced selectivity for the HCV NS5B polymerase over host RNA polymerases. GS-6620 demonstrated a high barrier to resistance in vitro. Prolonged passaging resulted in the selection of the S282T mutation in NS5B that was found to be resistant in both cellular and enzymatic assays (>30-fold). Consistent with its in vitro profile, GS-6620 exhibited the potential for potent anti-HCV activity in a proof-of-concept clinical trial, but its utility was limited by the requirement of high dose levels and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global health problem, with an estimated 180 million individuals chronically infected with the virus (1). The infection is the leading cause of end-stage liver disease and liver cancer in North America and Europe (2). It is estimated that in 2007, HCV surpassed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as a cause of death, and the disease burden has continued to grow as the duration of infection has increased for those initially infected (3).

The recent regulatory approval of two HCV nonstructural protein 3/4A (NS3/4A) protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, has led to increased treatment response rates when given in combination with pegylated interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) for those with an HCV genotype 1 infection. However, these regimens are limited by the emergence of viral resistance, increased adverse events, inability to treat patients who are intolerant or contraindicated to IFN treatment, and decreased efficacy in many patient populations who are most in need of therapy, including those with advanced liver diseases and those infected with other HCV genotypes (4). Nucleotide inhibitors (NIs) have demonstrated great promise as direct-acting antivirals with broad genotype coverage, lack of preexisting variants with reduced susceptibility, a high barrier to resistance, and the ability to produce potent and durable antiviral responses (5–7). Following intrahepatic activation involving nucleotide kinases, the active 5′-triphosphates of NIs target the HCV nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase by serving as alternative substrates and nonobligate chain terminators of viral RNA synthesis. The initial HCV NIs to enter clinical trials were N-nucleosides, containing the natural C-N glycosidic linkage, with either 2′-C-Me or 4′-azido as the substituted ribose sugars (5, 8).

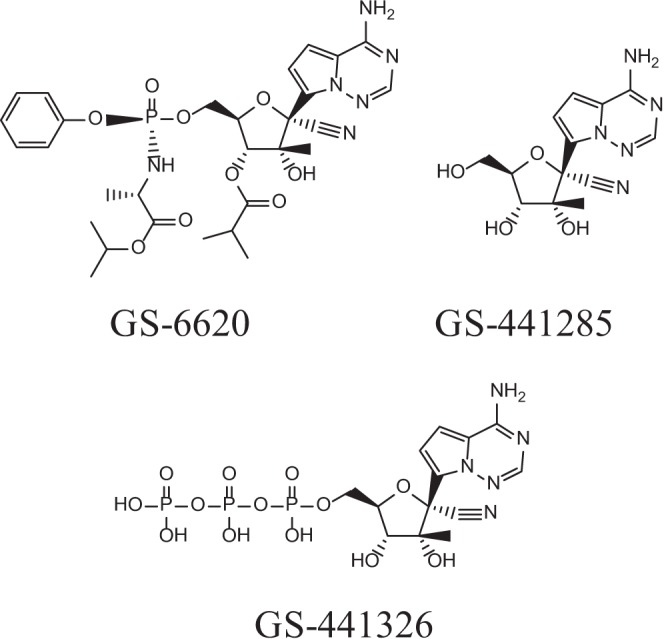

Recently, we reported the discovery of a C-nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitor, GS-6620 (9) (chemical structure shown in Fig. 1). GS-6620 is a pangenotype inhibitor with additive-to-synergistic effects when combined with other classes of HCV antivirals in vitro. The pharmacologically active metabolite of GS-6620, 1′-CN-2′-C-Me-4-aza-7,9-dideaza-A 5′-triphosphate (TP) (GS-441326), is a potent inhibitor of NS5B and is not a substrate for the mitochondrial RNA polymerase, a potential off-target that may lead to toxicity that has been observed for some HCV NIs (9, 10). Cross-resistance studies showed that GS-6620 had reduced activities against genotype 1b (GT1b) replicons carrying the S282T NS5B mutation. In this study, we fully characterized the pharmacology of GS-6620 in vitro. The reported studies include the activity of GS-6620 against HCV genotype 1 to 6 replicons and infectious genotype 2a virus, antiviral activity against a panel of RNA and DNA viruses, and detailed kinetic characterization of the interaction of GS-441326 with the NS5B polymerase. We also evaluated the potential for general and mitochondrial cytotoxicity of GS-6620 using cell- and enzyme-based assays. The potential for cross-resistance with other NIs and additional HCV inhibitor classes was assessed using resistant mutants selected by NS5B nonnucleoside inhibitors (NNIs), protease NS3/4A inhibitors (PIs), and NS5A inhibitors. Resistance selections with GS-6620 were also conducted using both the infectious genotype 2a virus and the genotype 1b replicon.

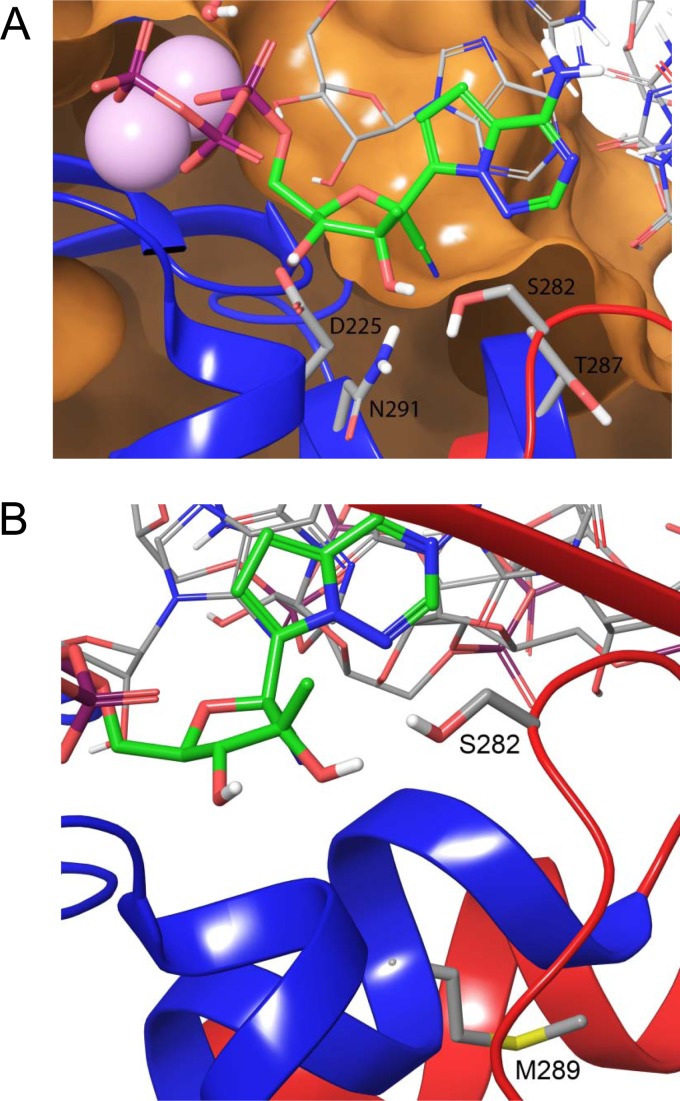

FIG 1.

Chemical structures of GS-6620, its nucleoside metabolite GS-441285, and active triphosphate metabolite GS-441326.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

GS-6620 [(Sp)-isopropyl 2-((S)-(((2R,3R,4R,5R)-3-isobutyroxy-5-(4-aminopyrrolo[1,2-f][1,2,4]triazin-7-yl)-5-cyano-4-hydroxy-4-methyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)methoxy) (phenoxy)phosphorylamino)propanoate] and other NIs were synthesized by Gilead Sciences, Inc. unless mentioned otherwise. The NS3 protease inhibitor BILN-2061 [14-cyclopentyloxycarbonylamino-18[2-(2-isopropylamino-thiazol-4-yl)-7-methoxy-quniolin-4-yloxy]-2,15-dioxo-3,16-diaza-tricyclo(14.3.0.0)nonadec-7-ene-4-carboxylic acid] and the nucleoside 2′-C-methyl adenosine (2′CMeA) [2-(6-amino-purin-9-yl)-5-hydroxymethyl-3-methyl-tetrahydro-furan-3,4-diol] were purchased from Acme Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA). All natural deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) were from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). The [α-33P]dNTPs and [α-33P]NTPs were purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). The 3′-deoxy NTPs were from TriLink BioTechnologies (San Diego, CA). Aphidicolin, α-amanitin, and alpha interferon (IFN-α) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

DNA and RNA oligonucleotides.

A 244-nucleotide (nt) heteropolymeric RNA lacking secondary structure (short small hairpin RNA [sshRNA]) with the sequence 5′-(UCAG)20(UCCAAG)14(UCAG)20-3′ was used as the template in the NS5B enzymatic assay and was designed and prepared as described previously (11). An RNA dimer, GpC [guanylyl(3′→5′)cytidine], was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and was used as the primer for RNA synthesis. GpC was labeled with 5′-32P by incubating in a 25-μl mixture containing 10 μl of 8 mM GpC, 10.5 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), 20 units T4 kinase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), and 2.5 μl T4 kinase buffer at 37°C for 30 min. The mixture was heated at 90°C for 2 min and subsequently diluted with 187.5 μl of water to reach a final concentration of 0.2 mM labeled [32P]GpC. This final mixture was used directly in the RNA elongation assays. The trace amount of residual [γ-32P]ATP had no impact on the assay (data not shown). A 16-nucleotide (nt) RNA template (R16) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was used in the NTP analog incorporation and chain-termination assays. It was synthesized and PAGE purified by Thermo Scientific/Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Cells.

The differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma Huh-7 cell line was obtained from the JCRB Cell Bank (Japan). The human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-1)-transformed human T-lymphoblastoid cell line MT-4 was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD). The hepatoblastoma cell line HepG2 and the prostate metastatic carcinoma cell line PC-3 were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from human buffy coats obtained from normal healthy volunteers (Stanford Medical School Blood Center, Palo Alto, CA). For quiescent PBMC cultures, the total cells were seeded in 96-well plates, followed by immediate drug treatment. Stimulated PBMCs were cultured in the presence of 10 units per ml of recombinant human interleukin-2 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and 1 μg per ml phytohemagglutinin-P (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h prior to drug treatment. Human primary hepatocytes were obtained from either Celsis In Vitro Technologies (Baltimore, Maryland) or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Human primary bone marrow (BM) light-density cells from three different lots were obtained from AllCells (Emeryville, CA) or Lonza (Walkersville, MD), and the cytotoxicity studies were conducted by Stemcell Technologies (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada).

Enzymes.

The coding sequences of NS5B polymerase from genotype 1b (Con1 strain) and 2a (JFH1 strain) were PCR amplified from plasmids carrying the I389luc-ubi-neo/NS3-3′/ET replicon and pJFH1, respectively. The 3′-PCR primers were designed to encode a construct excluding the C-terminal 21 (or 55) amino acids of full-length NS5B and including a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. The resulting PCR fragments from the Con1 and JFH1 strains were cloned into pET21a and pET30a protein expression vectors (Invitrogen), respectively, yielding plasmids pET21-NS5B(1b)Δ21(or Δ55)C6His and pET30-NS5B(2a)Δ21C6H. Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Wild-type and mutant NS5B proteins were overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified according to published protocols (12). Recombinant human DNA polymerases α and β were gifts from Robert Kuchta at the University of Colorado and Zucai Suo at the Ohio State University, respectively. Recombinant human DNA polymerase γ (including both the large subunit and the small subunit) was cloned, overexpressed, and purified based on published methods (13, 14). RNA polymerase II was purchased as part of the HeLaScribe nuclear extract in vitro transcription system kit from Promega (Madison, WI). The recombinant human mitochondrial RNA polymerase was purchased from Enzymax (Lexington, KY).

HCV subgenomic replicons.

Genotypes 1a-H77 and 1b-Con1 subgenomic replicons were generated as described previously (15, 16). Stable genotype 2a JFH1 Rluc subgenomic HCV replicon cells were created using plasmid pRLucNeo2a that encodes a bicistronic genotype 2a subgenomic replicon with the Renilla luciferase reporter in the first cistron. Plasmid pRLucNeo2a was derived from the plasmid pLucNeo2a containing the nonstructural genes of genotype 2a JFH1 strain and a firefly luciferase reporter (17). The firefly luciferase-neo gene of pLucNeo2a was replaced by the Renilla luciferase-neo gene in the plasmid pRlucNeo2a, as described previously (15). Briefly, the fragment encoding the Renilla luciferase-neo reporter gene was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pF9A (Promega) using primers, with the addition of AfeI and NotI restriction sites (underlined) at the ends (AfeIRlucNeoF, 5′-ATA GCG CTA TGG CTT CCA AGG-3′ and RlucneoNotIR, 5′-AAT GCG GCC GCT CAG AAG AAC-3′) and subsequently cloned into a pTA TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The plasmid pRlucNeo2a was then generated by the ligation of the TOPO-cloned AfeI-NotI fragment containing Renilla luciferase-neo into the plasmid vector pLucNeo2a digested with the same enzymes. The final sequence of plasmid pRLucNeo2a was confirmed by DNA sequencing. In vitro-transcribed replicon RNA (12 μg) of pRlucNeo2a was transfected into Huh-7-Lunet cells by electroporation, and the clonal cell line 2a Rluc-15 was selected for antiviral assays, as described previously (15).

Stable genotype 3a Rluc subgenomic HCV replicon cells were established with a plasmid (pGT3aS52NeoSG) that encodes a subgenomic genotype 3a replicon based on the S52 infectious clone (GenBank accession no. GU814263), as published previously (18). Stable genotype 4a (ED43 strain) Rluc subgenomic HCV replicon cells were established as described previously (19). A genotype 5a chimeric replicon was generated with a consensus NS5B sequence of genotype 5 derived from the European HCV database, as described earlier (20, 21).

Stable genotype 6a Rluc subgenomic HCV replicon cells were established with a plasmid pGT6aNeoSG that carries a bicistronic genotype 6a replicon based on the consensus sequence of 16 genotype 6a genomes available in the European HCV database and the 2a JFH1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (230 nt). pGT6aNeoSG was prepared by DNA synthesis and cloning (GenScript). Plasmid pGT6aRlucNeoSG was generated from the pGT6aNeoSG plasmid as described above for plasmid pRLucNeo2a. The stable genotype 6a subgenomic replicon cell line was established in the same way as the above stable genotype 3a subgenomic replicon.

Establishment of genotype 2a infectious HCV.

The cell culture-adapted genotype 2a-JFH1 virus was established in Lunet-CD81 cells as described previously (22).

Antiviral assays against genotypes 1 to 6 subgenomic HCV replicon cells.

Genotype 1a-H77, 1b-Con1, 2a-JFH1, 3a-S52, 4a-ED43, and 6a-HK HCV replicon cells were seeded into 384-well plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well, as described previously (23). Genotype 5a NS5B chimeric replicon cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 4,000 cells/well (21). The assay plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 85% humidity, after which the cell culture medium was removed and the cells were assayed for luciferase activity as a marker for replicon levels. Luciferase activity was quantified by using a Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) for inhibiting replicon replication and the 50% concentration inhibiting cell viability (CC50) were reported.

Antiviral assays against genotype 2a infectious HCV.

Lunet-CD81 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 4 × 103 cells per well in 100 μl of complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM). The cells were allowed to attach overnight and then compounds were added in a medium volume of 50 μl. The compounds were serially diluted in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a 3-fold dilution series and then added at a 1:50 dilution to complete DMEM before being transferred to the cell culture wells. Immediately following the compound addition, virus was added to the cells in a volume of 50 μl and at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. The final compound dilution was therefore 1:200, with a final DMSO concentration of 0.5%. The cell plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 days, after which the culture medium was removed and the cells were assayed for viral replication levels. The proteolytic activity of viral-expressing NS3 protease was measured as a marker for viral replication using an europium-labeled NS3 peptide substrate, and the EC50s were determined as described previously (17).

Antiviral screening against other viruses.

The antiviral activity of GS-6620 was determined against a panel of non-HCV viruses, including bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), West Nile virus, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, human rhinovirus (HRV), coxsackievirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, vaccinia virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Detailed information regarding the virus strains, cell lines, and incubation duration is shown on Table S2 in the supplemental material. In general, virus and cells were mixed in the presence of test compound, incubated for 4 to 10 days, and measured for the reduction in viral cytopathic effects (CPE). The antiviral effect of GS-6620 against HBV was monitored by HBV DNA quantification using real-time PCR (24). Whenever applicable, the titers of viruses were determined beforehand, such that the control wells exhibited 85 to 95% loss of cell viability. The EC50s and CC50s were reported.

Cytotoxicity.

Huh-7, HepG2, PC-3, and MT-4 cells, primary hepatocytes, quiescent PBMCs, and stimulated PBMCs were treated with GS-6620 for 5 days; cell viability was measured using the intracellular ATP level (CellTiter-Glo; Promega), and the luminescence signal was quantified using an EnVision luminescence plate reader (PerkinElmer). The CC50 value was defined as the concentration at which there was a measured 50% decrease in cell viability. The data were analyzed using the Pipeline Pilot software (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) or GraphPad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA). Unless otherwise mentioned, CC50 values were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis using a sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) equation (four-parameter logistic equation): Y = bottom + (top − bottom)/(1 + 10[[logCC50 − X] × HillSlope]), where the bottom and top values were fixed at 0 and 100, respectively. X is the log of the concentration of the test compound and Y is the response of the untreated control. The Hill slope (or Hill coefficients) represents the largest absolute slope of the dose-response curve.

Mitochondrial DNA content determination.

The assay was modified based on a previously published method (25). HepG2 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. Following attachment, the medium was replaced with 1.0 ml of fresh medium containing tested compounds and incubated for 10 days. The medium was replaced with fresh medium and compounds every 3 to 4 days. The DMSO concentration was normalized to 1.0% for all treatments. Following the incubation, the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the total DNA was extracted from the cells using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCRs were performed using TaqMan universal mastermix (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in an ABI Prism 7900HT fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The quantification of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was achieved by the amplification of a fragment of the mitochondrion-specific cytochrome b gene, described in detail in the supplemental material. Chromosomal DNA was quantified by the amplification of a fragment of the β-actin gene using a β-actin Assay-on-Demand kit (Applied Biosystems). The final results are presented as the mean percentage of mtDNA (± standard deviation [SD]) relative to the percentage of chromosomal DNA from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Mitochondrial biogenesis assay.

The compounds were tested starting at a concentration close to the CC50 value of the compound from a 5-day treatment. For compounds with a CC50 of ≥100 μM, the starting concentration was 100 μM. PC-3 cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 103 cells per well in a final assay volume of 100 μl per well, with a constant amount of DMSO equal to 0.5%. After a 5-day incubation, the cells were analyzed with the MitoTox MitoBiogenesis in-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MitoSciences/Abcam, Eugene, OR), which uses quantitative immunocytochemistry to measure the protein levels of a mitochondrial DNA-encoded protein (cytochrome c oxidase 1 [COX1]) and a nuclear DNA-encoded protein (succinate dehydrogenase [SDH-A]) in cultured cells. The cells were fixed in 96-well plates and the target proteins were detected with highly specific and well-characterized monoclonal antibodies. Protein levels were quantified with IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies. Infrared (IR) imaging and quantitation were performed using a Li-Cor Odyssey instrument (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). All ratios were expressed as a percentage of the 0.5% DMSO control. In cases where the cell viability was severely affected, the data for mitochondrial biogenesis were not included for analysis due to significant errors associated with low signals. Chloramphenicol was used as a positive control for the assay.

Cross-resistance studies.

For the genotype 1b or 2a NS5B mutant HCV replicons and genotype 1b NS3/4A and NS5A mutant replicons, mutations were introduced into the genotype 1b or 2a parental replicons using a QuikChange II XL mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After confirming the mutations by DNA sequencing, replicon RNA was transcribed in vitro from replicon-carrying plasmids using a MEGAscript T7 kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Mutation replicon RNAs were transfected into Huh-7-Lunet cells and their susceptibilities to GS-6620 were determined as described previously (16, 23).

Selection of GS-6620-resistant J6/JFH1 viruses.

Naive Lunet-CD81 cells were infected with the cell culture-adapted J6/JFH1 virus at an MOI of 3.0, as described previously (22). The infected cells were maintained in the presence of GS-6620 or other nucleos(t)ide analog HCV inhibitors, starting at a concentration of 1× EC50. The infected cells were passaged every 3 to 4 days until viral CPE was observed. The viral supernatants were then passaged over naive Lunet-CD81 cells at escalating drug concentrations for continuous selection, as previously described (17). The determination of viral titers (50% tissue culture infectious dose [TCID50] assay) is described in the supplemental material.

Selection of GS-6620-resistant genotype 1b HCV replicon.

Genotype 1b-Rluc-2 cells (6 × 105) were seeded in a 150-mm-diameter cell culture dish. After overnight culture, the cells were treated with GS-6620 at a concentration of 1.5 μM (5× EC50) in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml G-418. The cell culture medium was refreshed every 2 days with fresh compounds until massive cell death occurred. When the cell colonies grew and reached 90% confluence, the cells were split 1:3 and the GS-6620 concentration was increased 2-fold. The GS-6620 concentration was progressively increased until cell growth became stable in the presence of 50 μM GS-6620. The cell pellets were collected and stored for genotypic analysis as described in the supplemental material.

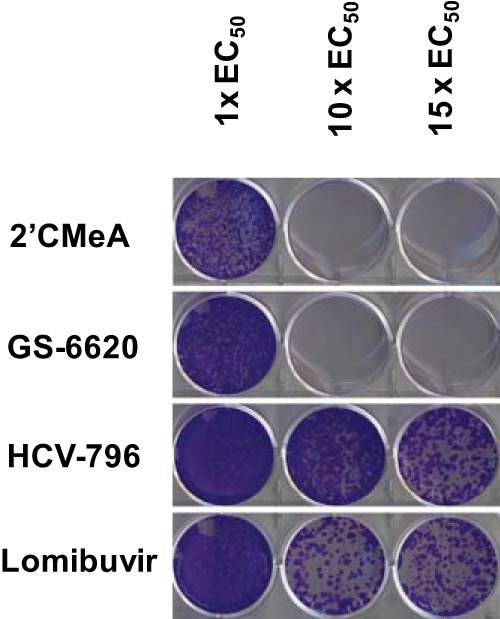

Resistance barrier assessment by replicon colony reduction assay.

Huh-9-13 replicon cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. Twenty-four hours postseeding, the cells cultured in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml of G-418 were treated with either GS-6620, 2′-C-Me-A, HCV-796 (HCV NNI), or lomibuvir at 1, 10, or 15× EC50 concentrations using the predetermined EC50s of 500 nM, 300 nM, 3 nM, and 4 nM for GS-6620, 2′-C-Me-A, HCV-796, and lomibuvir, respectively. The culture medium was replaced with freshly prepared compound-containing medium every 72 h. After 21 days in culture, the medium was removed and the cells were fixed in 20% methanol solution and stained with crystal violet.

Biochemical assays.

All of the biochemical assays used radiolabeled dNTP or NTP to track DNA or RNA product formation. The products were analyzed using affinity filter-binding or electrophoresis systems and quantified using a Typhoon Trio imager and ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare). All concentrations refer to the final concentrations unless mentioned otherwise. Product formation in the presence of the inhibitors was expressed as a percentage of the product in water-treated controls (defined as 100%). The IC50 was defined as the concentration at which there was a 50% decrease in product formation. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. IC50s were calculated as an average of at least three independent experiments.

Inhibition of NS5B.

A reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.2 U/μl RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega), 4 ng/μl sshRNA, 5 mM MgCl2, and 70 to 150 nM wild-type or mutant HCV NS5B was preincubated with NTP analogs for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction was initiated by adding a mixture containing 2.5 μM ATP, 2.5 μM CTP, 2.5 μM UTP, 1.25 μM GTP, and 0.06 μCi/μl of [α-33P]GTP (3,000 mCi/mol). The reactions were allowed to proceed for 90 min at 30°C. After 90 min, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was spotted on DE81 anion exchange paper (Whatman, United Kingdom), which was then washed with 3× Na2HPO4 (125 mM [pH 9]), 1× water, and 1× ethyl alcohol (EtOH). The filter paper was air-dried and exposed to the phosphorimager screen, and the amount of synthesized RNA was quantified as described earlier.

Mode of inhibition and Ki measurements for inhibitors.

The assay setup was similar to the IC50 assay described above except that the inhibition of NS5B by the analogs was measured at various concentrations of ATP (2.5, 5, and 10 μM). The reactions were allowed to proceed for 70 min at 30°C, and 2 μl of the reaction mixture was spotted on DE81 anion exchange paper (Whatman, United Kingdom) that was washed with 3× Na2HPO4 (125 mM [pH 9]), 1× water, and 1× EtOH. The filter paper was air-dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen. RNA product formation was plotted as a function of the natural NTP concentration at each different NTP analog concentration. The Ki values were calculated by globally fitting the data using a mixed inhibition model, using the following equations: VmaxApp = Vmax/(1 + I/[α × Ki]), KmApp = Km × (1 + I/Ki)/(1 + I/[α × Ki]), and Y = VmaxApp × X/(KmApp + X), where X and I are the concentrations of the natural NTP and its analog, respectively (GraphPad Prism 5.0). The value of α indicates the mode of inhibition. When α is 1, noncompetitive inhibition is indicated, when α is ≫1, competitive inhibition is indicated, and when α is >0 and <1, uncompetitive inhibition is indicated (26).

Single nucleoside incorporation and chain termination of RNA synthesis.

The incorporation of NTP analogs was studied using a 5′-33P-labeled GpC primer and an R16 template. As shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, the first position for an ATP or ATP analog incorporation is +8 nt beyond the GpC primer. A reaction mixture containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 10 mM DTT, 20 μM R16, 20 μM GpC, 4.7 μM NS5B (Con1, Δ55, C6His), and 5 mM MgCl2 was preincubated at room temperature for 5 min. The reaction was started by adding 100 μM CTP and 100 μM UTP, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 15 min at 25°C, followed by adding a mixture containing 10 μM ATP analog in the presence or absence of 100 μM GTP. After incubation at 30°C for 30 min, 15 μl of the reaction mixture was quenched with 5 μl 0.25 M EDTA in a gel loading buffer (50% formamide and bromophenol blue) to reach a final concentration of 35 μM EDTA. The samples were heated at 65°C for 5 min, run on a 25% polyacrylamide gel (8 M urea), and exposed to a phosphorimager screen prior to quantification and analysis.

Inhibition of human DNA and RNA polymerases.

All reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 2 mM DTT, 0.05 mg/ml activated fish sperm DNA, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.3 μCi [α-33P]dTTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), and 2 μM each of dATP, dGTP, and TTP. The optimal enzyme concentrations were chosen to be in the linear range of enzyme concentration ([E]) versus activity, and the reaction time was selected to ensure that <10% of the substrate was consumed. All reactions were run at 37°C. The amounts of enzyme used in each assay were 160 nM and 30 nM for polymerase α and β, respectively. For polymerase γ holoenzyme, 1.2 nM large catalytic subunit and 3.6 nM small accessory subunit were used in the assay. The incubation times were 30 min, 10 min, and 60 min for polymerases α, β, and γ, respectively. The reactions were started by adding a mixture of the abovementioned natural NTPs and MgCl2 into a preincubated mixture containing enzyme and inhibitors. At the end of the incubation, 5 μl of the reaction mixture was removed and spotted on DE81 anion exchange paper (Whatman, United Kingdom), which was washed with 3× Na2HPO4 (125 mM [pH 9]), 1× water, and 1× EtOH. The filer paper was air-dried and exposed to the phosphorimager screen prior to quantification and analysis.

Human RNA polymerase (Pol) II reactions were conducted by preincubating 7.5 μl 1× transcription buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.2 to 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 20% glycerol), 3 mM MgCl2, 100 ng cytomegalovirus (CMV)-positive control DNA (Promega), a mixture of natural NTPs, and various concentrations of the inhibitors at 30°C for 5 min. The mixture of four natural NTPs contained 5 μCi of the competing NTP, with the concentration set at the Km, and 400 μM the three noncompeting NTPs. The reaction was started by adding 3.5 μl of HelaExtract to a final 25-μl reaction mixture. After 1 h incubation at 30°C, the polymerase reaction was stopped by adding 10.6 μl of proteinase K mixture, which contained final concentrations of 2.5 μg/μl proteinase K (New England BioLabs), 5% SDS, and 25 mM EDTA. After incubation at 37°C for 3 to 12 h, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was mixed with 10 μl of the loading dye (98% formamide, 0.1% xylene cyanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue), heated at 75°C for 5 min, and loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel (8 M urea). The gel was dried for 45 min at 70°C and the full-length product (363 nt runoff RNA) was quantified.

The inhibition of mitochondrial RNA polymerase (POLRMT) was evaluated using 20 nM POLRMT preincubated with 20 nM template plasmid (pUC18-LSP) containing POLRMT light-strand promoter region and mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA) (100 nM) and mtTFB2 (20 nM) in buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 10 mM MgCl2 (27). The reactions were heated to 32°C and initiated by adding 2.5 μM each of the four natural NTPs and 1.5 μCi of [33P]GTP. After incubation for 30 min at 32°C, the reactions were spotted on DE81 paper before being processed for quantification.

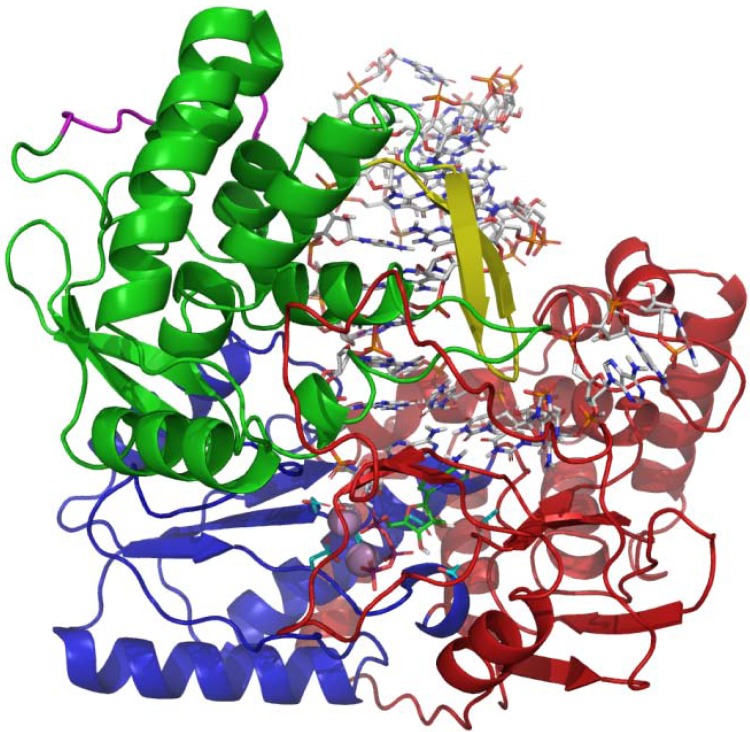

Modeling of GS-441326 in the NS5B active site.

We constructed a model of elongating genotype 1b NS5B based on the NS5B 2a Δ21-Δ8 primer–template-bound structure (4E7A) published by Mosley et al. (28). An analysis of this structure suggested it had some elements necessary for binding double-stranded RNA (dsRNA); however, the RNA observed in the structure was not properly positioned to be catalytically competent. We thus modified the structure based on the structures of poliovirus (3OL7) (29) and Norwalk virus (3BSO) (30) polymerases. The poliovirus polymerase and the NS5B structures were overlaid based on α-carbon superposition of active site residues. Primer/template, metals, and substrate from the poliovirus structure were then merged into the NS5B structure. Some side-chain minimization surrounding the RNA was required, but otherwise, this RNA was a good fit. The metals were modified from Mn2+ to Mg2+. Active site side chains (particularly D225 and S282) were manipulated into conformations consistent with the poliovirus and Norwalk structures and subsequently minimized, constraining the coordination of the metals using MacroModel OPLS-AA/GB/SA (suite 2012, version 9.9; Schrödinger, New York, NY). Additional side chains were conformationally sampled using Prime (suite 2012, version 3.1; Schrödinger). The β-loop was manually incorporated and optimized with MacroModel dynamics. Finally, the structure was mutated to conform with those of other genotype sequences (including 1b-Con1), and side chains were reoptimized with Prime. In brief, the structural changes required to bind the RNA product are relatively minimal in our model. With respect to apo structures, the palm domain remains essentially unchanged (root mean square deviation [RMSD], 0.5 Å) while the fingers move by ∼1 Å and the thumb moves by ∼2 Å. In particular, the largest structural rearrangements occur at the interface of the C-terminal tail/thumb domain and the β-loop/C-terminal tail, which form the moving parts that rearrange to accommodate RNA product. The final genotype 1b-Con1 NS5B structure is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG 2.

Model of elongating NS5B, based on the structure of Mosley et al. (28) and structures of poliovirus (29) and Norwalk virus (30). The palm domain is shown in blue, the fingers are red, the thumb is green, and the beta loop is yellow.

RESULTS

Anti-HCV activity and specificity of GS-6620.

The anti-HCV activity of GS-6620 was evaluated using a panel of genotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 3a, 4a, 5a, and 6a subgenomic replicons. Different from the genotype 3, 4, and 6 NS5B chimeric replicons used in our earlier report (9), all of the replicons used in this study were subgenomic replicons, except genotype 5a, which is a chimeric replicon with genotype 5a (GT5a) NS5B sequence engineered into a genotype 1b backbone. GS-6620 showed potent activities against the replicons of all six genotypes, with EC50s ranging from 0.05 to 0.68 μM (Table 1). It is also active against the infectious genotype 2a-J6/JFH1 virus, with an EC50 of 0.25 μM. GS-6620 showed no cytotoxicity toward any of the replicon cells or clone-5 cells at the highest concentration tested (90 or 50 μM). It is worth mentioning that the recent reclassification of HCV genotypes presents the need to study the efficacy of future HCV direct-acting antivirals on genotype 7, a currently poorly understood genotype (31).

TABLE 1.

Antiviral activity of GS-6620 against HCV replicon and infectious viruses

| HCV replication systema | GS-6620 |

2′CMeA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μM)b | CC50 (μM) | EC50 (μM)b | CC50 (μM) | |

| HCV repliconc | ||||

| GT1a | 0.18 ± 0.12 | >90 | 0.20 ± 0.12 | >90 |

| GT1b | 0.46 ± 0.28 | >90 | 0.20 ± 0.10 | >90 |

| GT2a | 0.68 ± 0.31 | >90 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | >90 |

| GT3a | 0.048 ± 0.001 | >90 | 0.091 ± 0.032 | >90 |

| GT4a | 0.11 ± 0.06 | >90 | 0.16 ± 0.07 | >90 |

| GT5a | 0.14 ± 0.02 | >90 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | >90 |

| GT6a | 0.11 ± 0.05 | >90 | 0.031 ± 0.004 | >90 |

| HCV infectious virusd | ||||

| GT2a J6/JFH-1 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | >50 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | >50 |

GT, genotype.

Values are the average ± SD from at least three independent experiments.

All replicons are full-length Rluc replicons except genotype 5a, which is a chimeric replicon with genotype 5a NS5B sequence engineered into a genotype 1b backbone. Part of the data has been published (9).

Clone-5 cells obtained from cured Huh-7 genotype 1b replicon clone were used in this study.

To establish the antiviral specificity of GS-6620, the compound was tested against a panel of RNA and DNA viruses (Table 2). Within the closely related Flaviviridae family, only the BVDV replicon showed appreciable inhibition by GS-6620, with an EC50 of 1.5 μM, while BVDV infectious virus, West Nile, and yellow fever viruses were not inhibited by GS-6620. Weak activity was found against different strains of human rhinovirus (HRV) (EC50, 19 to 78 μM) but not against coxsackievirus in the Picornaviridae family. Similarly, GS-6620 showed no inhibition of a group of negative-strand RNA viruses, including human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus, and influenza virus, or with reverse transcriptase-containing viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV), at the highest concentration tested. Interestingly, GS-6620 was moderately active against vaccinia virus, a complex double-stranded DNA virus in the Poxviridae family, with an EC50 of 8 μM that was also confirmed with an alternative prodrug closely related to GS-6620 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Antiviral activity of GS-6620 against other viruses

| Viruses by type and family | GS-6620 |

Positive controls |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50a (μM) | CC50 (μM) | Compoundb | EC50 | CC50 | |

| Positive-strand RNA viruses | |||||

| Flaviviridaec | |||||

| BVDV replicon | 1.5 | 29 | MK-608 | 0.066 μM | >50 μM |

| BVDV | >30 | >30 | rIFN-α | 10.1 IU/ml | >500 IU/ml |

| West Nile virus | >30 | >30 | rIFN-α | 8.26 IU/ml | >500 IU/ml |

| Dengue virus type 2 | >30 | >30 | RBV | 29.6 μg/ml | >200 μg/ml |

| Yellow fever virus | >30 | >30 | rIFN-α | 10.1 IU/ml | >500 IU/ml |

| Picornaviridae | |||||

| HRV 1A | 57 | >100 | Rupintrivir | 40 μM | >100 μM |

| HRV 1Bc | 19 | >30 | Enviroxime | 0.22 μg/ml | >100 μg/ml |

| HRV 10 | 78 | >100 | Rupintrivir | 44 μM | >100 μM |

| Coxsackievirusc | >30 | >30 | RBV | 11.3 μg/ml | >100 μg/ml |

| Negative-strand RNA viruses | |||||

| Paramyxoviridae | |||||

| RSV | >100 | >100 | YM-53403 | 0.3 μM | >100 μM |

| Parainfluenza virusc | >30 | >30 | Enviroxime | 13 μg/ml | >100 μg/ml |

| Orthomyxoviridae | |||||

| Influenza A (H3N2) virus | >100 | >100 | Favipiravir | 1.3 μM | >100 |

| Influenza A (H1N1) virus | >100 | >100 | Favipiravir | 1.5 μM | >100 |

| dsDNA virusd | |||||

| Vaccinia virus | 8 | >100 | Rifampin | 25 μM | >500 μM |

| RT-containing virusese | |||||

| HIV | >100 | >100 | AZT | 0.023 μM | >50 μM |

| HBV | >100 | >100 | TFV | 9.0 μM | >50 μM |

Values are based on average of at least three independent experiments and reported as average ± SD.

rIFN-α, recombinant alpha interferon; AZT, zidovudine; TFV, tenofovir.

A GS-6620-containing diastereomeric mixture was used in the assay.

dsDNA, double-stranded DNA.

RT, reverse transcriptase.

Inhibition of NS5B and mechanism of action for GS-441326.

GS-441326, the pharmacologically active 5′-triphosphate metabolite of GS-6620 (chemical structure shown in Fig. 1) was tested as an inhibitor for NS5B-catalyzed RNA synthesis using recombinant NS5B polymerase derived from genotype 1b (Con1) and genotype 2a (JFH1) replicon sequences. The IC50s and Ki/Km values are summarized in Table 3. GS-441326 was a potent inhibitor of HCV NS5B polymerase, with IC50s of 0.39 and 1.3 μM and Ki/Km values of 0.23 and 0.18 for NS5B genotypes 1b and 2a, respectively. It was 12- to 14-fold-more potent than 2′CMeATP based on the Ki/Km values.

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of genotypes 1b and 2a NS5B polymerases by GS-441326

| Active triphosphate | Genotype 1ba |

Genotype 2aa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | Ki/Kmb | IC50 (μM) | Ki/Kmc | |

| GS-441326 | 0.39 ± 0.14 | 0.23 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.18 |

| 2′CMeATP | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 2.7 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 2.6 |

IC50s are reported as an average ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Genotype 1b-Conc1 and genotype 2a-JFH1 sequences were used for the NS5B cloning.

Km value for ATP with genotype 1b-Conc1 NS5B is 0.09 μM.

Km value for ATP with genotype 2a-JFH1 NS5B is 0.96 μM.

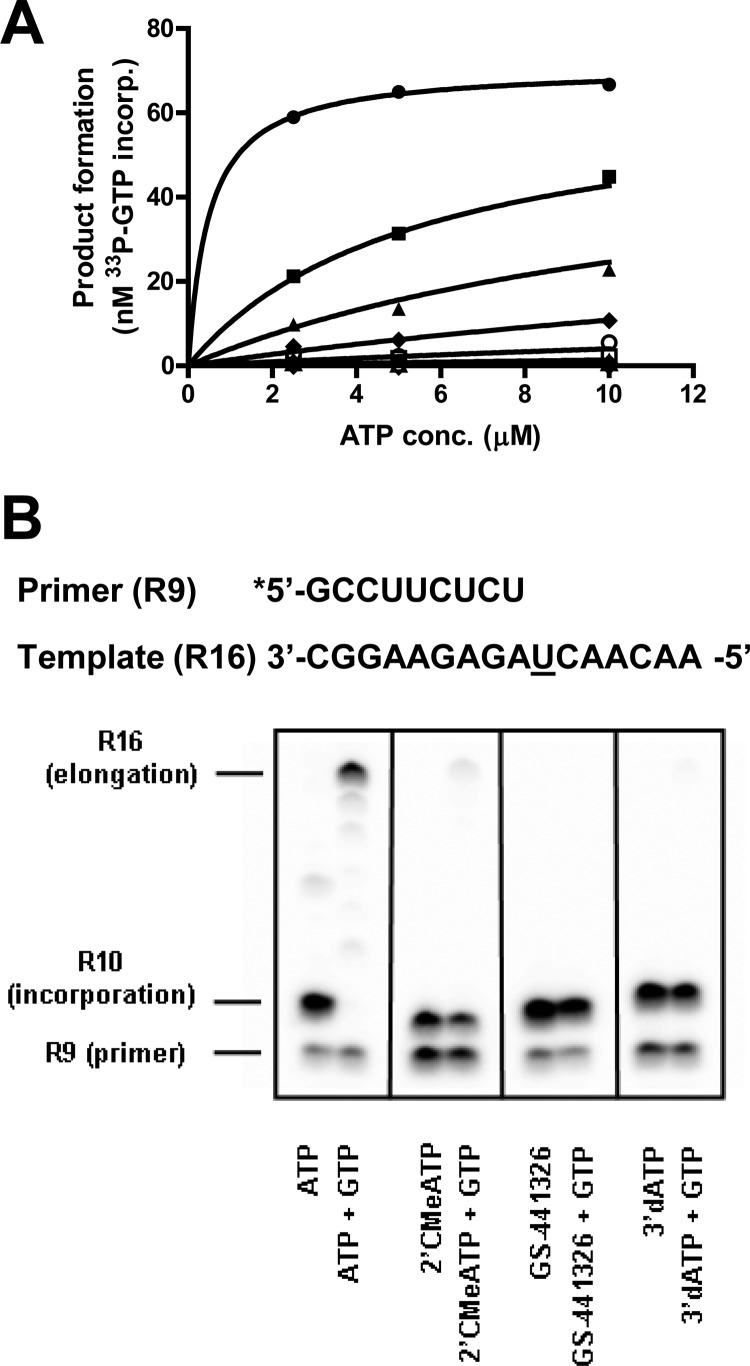

The mode of inhibition of GS-441326 was studied in the presence of increasing concentrations of ATP, and the data were fit with a nonbiased mixed inhibition model that yielded an α-factor of 140, with a global fit R2 of 0.998, indicating that GS-441326 is a competitive inhibitor of NS5B-catalyzed ATP incorporation (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, a detailed gel-based single nucleotide incorporation assay demonstrated that once incorporated, GS-441326 serves as a chain terminator similar to 2′CMeATP and 3′-deoxy ATP (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Inhibition of RNA synthesis by GS-441326 at different concentrations of ATP (A) and incorporation and chain termination by GS-441326 during NS5B-catalyzed RNA synthesis (B).

Evaluation of GS-6620 for general cytotoxicity, mitochondrial toxicity, and off-target effects on host polymerases.

GS-6620 and the major circulating metabolite observed after the administration of GS-6620, the nucleoside analog GS-441285 (structure shown in Fig. 1), as shown in an accompanying paper (32), were investigated for cytotoxicity in a panel of human cell lines derived from different tissues, including hepatic (Huh-7, HepG2), T-cell (MT-4), and prostate (PC-3) cells, as well as primary cells, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (unstimulated and stimulated cultures), primary hepatocytes, and human bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells (erythroid and myeloid). As summarized in Table 4, GS-6620 showed minimal cytotoxicity in Huh-7, HepG2, and PC-3 cells, with CC50 values of 40 to 67 μM. No cytotoxicity was observed in quiescent PBMCs, stimulated PBMCs, or primary hepatocytes at the highest concentration tested (100 μM). GS-6620 showed complex multiphasic effects on the MT-4 T-cell line and myeloid bone marrow progenitor cells and detectable toxicity in erythroid bone marrow progenitor cells (CC50, 15 μM). GS-441285 showed no effects on all cell types at the highest concentration tested (100 μM).

TABLE 4.

In vitro cytotoxicity of GS-6620 in human cell lines and primary cells

| Cell typea | CC50 (μM) withb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-6620 | GS-441285 | Puromycin | Fluorouracil | |

| Cell lines | ||||

| Hepatic | ||||

| Huh-7 | 67 ± 13 | >90 | 0.52 ± 0.19 | |

| HepG2c | 66 ± 13 | >90 | 0.65 ± 0.18 | |

| Prostate | ||||

| PC-3 | 40 ± 0.7 | >100 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | |

| T cell | ||||

| MT-4 | Complexd | >100 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | |

| Primary cells | ||||

| Hepatic | ||||

| Primary | >100 | >100 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | >100 |

| PBMC | ||||

| Quiescent | >100 | >100 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | >100 |

| Stimulated | >100 | >100 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | >100 |

| Bone marrow | ||||

| Erythroid | 15 ± 7 | >100 | NDf | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| Myeloid | Complexe | >100 | ND | 3.4 ± 0.8 |

Depending on the cell line, 90 μM or 100 μM was the highest concentration tested for each compound. All cells were treated for 5 days, except the bone marrow-derived progenitor cells, which were treated for 14 days.

CC50 values represent average ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Puromycin or fluorouracil was used as the positive control in all assays.

Galactose-adapted HepG2 cells were used in this study.

A complex multiphasic dose response was observed, with an initial drop in viability of 50% observed at 3.3 μM, followed by a rebound to >50% at higher concentrations. Flow cytometry studies showed the compound effect on cells was cytostatic instead of cytotoxic. In addition, MT-4 cell viability remained unchanged after a 6-week continuous culture with the compound.

Complex multiphasic behavior observed in myeloid cells, with an initial drop in viability of 50% observed at the concentrations of 1.5, 1.8, and 6.2 μM, respectively, in cells from three different donors. The viability of the cells rebounded to 30 to 40% at the highest concentration tested (100 μM).

ND, not determined.

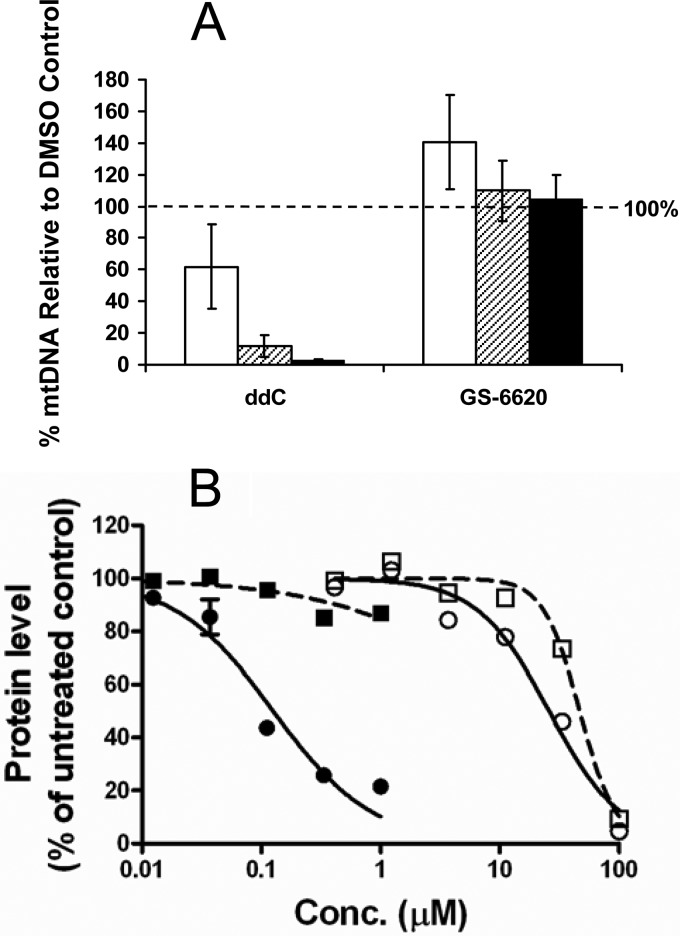

The potential risk of mitochondrial toxicity of GS-6620 was evaluated by measuring the mitochondrial DNA level and protein synthesis in treated HepG2 and PC-3 cells, respectively. After a 10-day incubation of HepG2 cells with GS-6620, the level of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was measured by real-time PCR and compared to the levels of chromosomal DNA. As shown in Fig. 4A, GS-6620 showed no inhibition of mtDNA level at the highest concentration tested (20 μM) in comparison to a >97% decrease by 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC), an HIV antiviral known as an inhibitor of human mtDNA polymerase (Pol) γ.

FIG 4.

Effect of GS-6620 on the level of mitochondrial DNA in HepG2 cells (A) and on the level of mitochondrial protein synthesis in PC-3 cells (B). (A) HepG2 cells were treated with compounds for 10 days and compounds were refreshed every 3 to 4 days. The three concentrations used were 0.2 μM (white bars), 2 μM (hatched bars), and 20 μM (black bars). (B) PC-3 cells were incubated with GS-6620 (open symbols) and dideoxycytosine (ddC) (closed symbols) for 5 days prior to analysis. The levels of mitochondrial DNA-encoded protein (COX-1, circles and solid lines) and nuclear DNA-encoded protein (SDH-A, squares and dotted lines) were plotted relative to the untreated controls.

The effect of GS-6620 on mitochondrial protein synthesis was evaluated in PC-3 cells using an in-cell ELISA-based MitoTox MitoBiogenesis assay. The cellular levels of a mitochondrial DNA-encoded COX1 and a nuclear DNA-encoded SDH-A proteins were monitored after 5-day incubation with GS-6620. GS-6620 showed no specific inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 4B). In contrast, ddC and chloramphenicol, an inhibitor of mitochondrial protein synthesis, showed selective inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis.

The inhibitory effect of GS-441326 was tested against a panel of human DNA and RNA polymerases, including DNA polymerases α, β, γ, and RNA polymerases II and mitochondrial RNA polymerase (POLRMT). Inhibition for the incorporation of radiolabeled dNTP or NTP (concentration = Km) was studied with heteropolymeric primer/templates using filter-binding or gel-based assays. GS-441326 showed no inhibition at the highest concentrations tested (200 or 500 μM) for any of the human DNA and RNA polymerases tested (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Inhibition of human DNA and RNA polymerases by GS-441326

| Human polymerases | GS-441326 | Positive controls |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM)a | Compound | IC50 (μM)b | |

| DNA Pol-αc | >200 | Aphidicolin | 1.6 ± 1.1 |

| DNA Pol-βc | >200 | 3′-Deoxy-TTP | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| DNA Pol-γc | >200 | 3′-Deoxy-TTP | 1.0 ± 0.6 |

| RNA Pol-IId | >200 | α-Amanitin | 0.0035 ± 0.0014 |

| POLRMT | >500 | 3′-Deoxy-GTPe | 4.2 ± 1.4 |

Values represent the average of at least three independent experiments.

IC50 values are reported as average ± SD.

The concentrations for dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and TTP were kept at 2 μM in the assay.

IC50s were measured under conditions where the competing NTP concentration was held at Km: 25 μM for ATP and 5 μM for GTP, UTP, and CTP. The Km values for each natural NTP were measured in the presence of 33P-labeled NTP of interest and 400 μM for the three other NTPs. The Km values are consistent with published data (40).

IC50s for 3′-deoxy-ATP, 3′-deoxy-CTP, and 3′-deoxy-UTP were 4.6, 1.4, and 4.7 μM, respectively.

Cross-resistance studies.

The cross-resistance profile of GS-6620 against known HCV drug-resistant mutants was studied using transient replicon assays. The panel of resistance mutations includes NS5B NI mutations (S282T and N142T), NS5B NNI mutations (M423T and Y448H/Y452H), protease NS3/4A inhibitor mutations (T54A, R155K, A156T, and D168V), and NS5A inhibitor mutations (L31V and Y93H). As summarized in Table 6, GS-6620 retained full activity against all of the mutations except S282T, which showed 39-fold resistance. All of the positive-control compounds showed fold resistance consistent with historical values.

TABLE 6.

Cross-resistance of known resistance mutations associated with different classes of HCV antivirals to GS-6620

| Mutationsa | GS-6620 (fold resistance)b | Positive controls |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | WT EC50 (nM)c | Fold resistance | ||

| NS5B NI | ||||

| S282T | 39 | 2′CMeA | 370 | 41 |

| N142T | 1.1 | 4′-Azido cytidine | 2,400 | 1.6 |

| NS5B NNI | ||||

| M423T | 0.76 | VX-222 | 17 | 80 |

| Y448H/Y452H | 0.80 | GS-9190 | 1.4 | 221 |

| NS3/4A | ||||

| T54A | 0.81 | Telaprevir | 520 | 3.5 |

| R155K | 0.93 | Telaprevir | 520 | 4.6 |

| A156T | 0.36 | BILN-2061 | 0.61 | >410 |

| D168V | 0.61 | BILN-2061 | 0.61 | >410 |

| NS5A | ||||

| L31V | 1.6 | BMS-790052 | 0.0029 | 17 |

| Y93H | 0.33 | BMS-790052 | 0.0029 | 44 |

Genotype 1b replicons (wild type or encoding the mutations) were transiently transfected into 1C cells. A GS-6620-containing diastereomeric mixture was used in these studies.

Fold resistance was calculated as the ratio of mutant EC50 to wild-type EC50. The values reported are the averages from at least three independent experiments. The S96T mutation was not studied due to its lack of fitness in transiently transfected replicons.

WT, wild type.

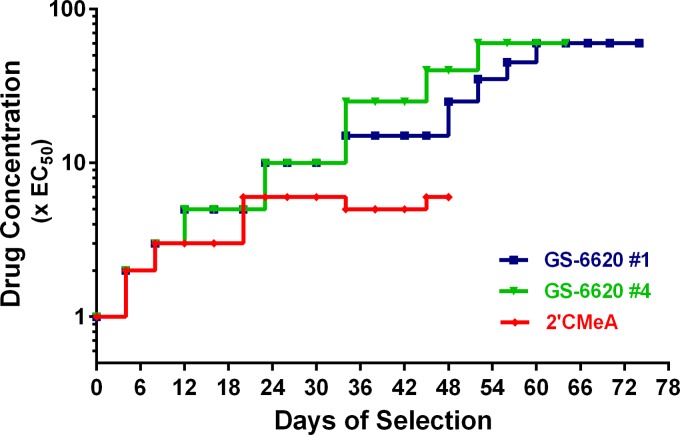

Resistance selection using genotype 2a infectious J6/JFH1 virus.

The selection of infectious viruses resistant to GS-6620 was performed with stepwise-escalating drug concentrations, as previously described (17). To determine the scope of drug resistance mutations, four independent selections were performed with GS-6620 (see Table S6 in the supplemental material) in parallel with NIs 2′CMeA and 2′CMeC as controls. The selection of drug-resistant viruses started at a drug concentration of 1× EC50 (0.25, 0.38, and 1.1 μM for GS-6620, 2′CMeA, and 2′CMeC, respectively). After 48 to 78 days of selection with escalating drug concentrations, infectious viruses with significantly reduced susceptibility were successfully selected at 60×, 6×, and 10× EC50 for GS-6620, 2′CMeA, and 2′CMeC, respectively. The selection charts for viruses resistant to GS-6620 (two representative experiments) and 2′CMeA are summarized in Fig. 5. The selection chart for the 2′CMeC resistant virus was very similar to that for 2′CMeA-resistant virus and is not shown in the figure.

FIG 5.

Representative resistance selection charts for GS-6620 and 2′CMeA-resistant viruses. The selection of drug-resistant viruses started at a drug concentration of 1× EC50. The infected cells were maintained in the presence of drug and were passaged every 3 to 4 days until viral CPE was observed. The viral supernatants were then passaged over naive Lunet-CD81 cells at escalating drug concentrations for continuous selection. Each symbol represents a passage of viral supernatant onto naive cells. The circles indicate the viral supernatants that were selected for genotypic analyses. The selection charts for GS-6620 selection no. 1 and no. 2 and 2′CMeA selection are shown in blue, green, and red, respectively.

Genotypic changes in the NS5B gene were determined throughout the resistance selection process by population sequencing. The emerging amino acid changes are listed in Table S6 in the supplemental material. At low drug concentrations (e.g., 3× EC50), although viruses were able to overcome drug pressure, no amino acid changes were observed in the NS5B gene from any of the selection experiments (data not shown). These results were confirmed by phenotypic analyses that showed no change in inhibitor susceptibility for these viruses. When the viruses were continuously selected at a higher drug concentration (6× EC50), a single substitution of serine to threonine at amino acid 282 (S282T) was identified in viral supernatants from the 2′CMeA and 2′CMeC selections. This finding is consistent with the knowledge that S282T in NS5B is the signature resistance-associated variant to 2′-C-Me nucleoside inhibitors. Interestingly, genotypic analyses of the viruses selected at 10× EC50 of GS-6620 identified substitutions of M289V in three independent selections and M289L in the fourth selection (see Table S6). At a higher drug concentration (60× EC50), population sequencing of the NS5B gene revealed that the resistant viruses retained the M289V/L mutation and acquired the S282T mutation (see Table S6). The substitution V421A in combination with M289V/L and S282T was also observed but appeared only once in the various selections.

All of the viruses shown in Table S6 in the supplemental material with genotypic changes in the NS5B gene were analyzed for phenotypic changes in drug susceptibility (Table 7). These analyses indicated that single substitutions in NS5B (M289V or M289L) were sufficient to confer low-level resistance to GS-6620, with an average of 4.4-fold increases in the EC50s. These two mutants were cross-resistant to 2′CMeA conferring an average 3.4-fold loss in susceptibility, but they were not cross-resistant to 2′CMeC (<1.6-fold). In contrast, the S282T mutant selected by 2′CMeA or 2′CMeC was highly resistant to both inhibitors, with average susceptibility losses of 33- and 19-fold, respectively. S282T alone also conferred significant resistance to GS-6620, with an average of 33-fold decrease in susceptibility. Viruses with a combination of either M289V or M289L and S282T had high-level resistance to GS-6620 (25- to 48-fold). However, this level of resistance was comparable to that conferred by S282T alone (within 2-fold). Not surprisingly, all the selected viruses remained fully susceptible to the NS3 protease inhibitor BILN-2061. These results indicate that in genotype 2a-J6/JFH1 virus, S282T is the primary resistance mutation (33-fold resistance) for GS-6620, while substitutions of M289L/V cause low levels of resistance to the compound (3- to 5-fold).

TABLE 7.

Phenotypic analyses of combinational NS5B mutations against GS-6620 in infectious virus antiviral activity assay

| Assay characteristics | EC50 (μM) | EC50 fold resistance by groupa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-6620 selection no. against indicated mutation: |

2′CMeA against S282T | 2′CMeC against S282T | |||||||

| 1 and 2 |

3 |

4 |

|||||||

| M289V | M289V, S282T | M289V | M289V, S282T, V421A | M289L | M289L, S282T | ||||

| Drug concn of virus (×EC50) | 10 | 60 | 10 | 60 | 10 | 60 | 6 | 6 | |

| NI usedb | |||||||||

| GS-6620 | 0.33 | 4.8 | 47.9 | 3.7 | 48.2 | 4.8 | 25.3 | 26.6 | 28.7 |

| 2′CMeA | 0.22 | 3.3 | 21.9 | 2.4 | 22.7 | 4.2 | 23.3 | 40.4 | 32.4 |

| 2′CMeC | 1.0 | 1.4 | 18.0 | 1.2 | 20.1 | 1.6 | 19.1 | 15.7 | 15.5 |

The values represent the average of two or more independent experiments. Fold resistance was calculated as the ratio of mutant virus EC50 to wild-type virus EC50.

The viruses were selected at a drug concentration of either 6×, 10×, or 60× EC50. Only the NS5B region was subjected to genotypic analysis.

Resistance selection of GS-6620 in HCV genotype 1b replicon.

Genotype 1b HCV replicon cells (1b-Rluc-2) were treated with progressively increasing concentrations of GS-6620 for 106 days, which resulted in the selection of a drug-resistant population. The resistant cells were expanded and assayed for susceptibility to GS-6620 and other related NIs. As shown in Table 8, GS-6620 lost 51-fold potency against the resistant replicon cells, which is similar to the 39-fold resistance found in the phenotypic analyses of the S282T mutant in the transient replicon replication assay using the genotype 1b replicon (Table 6). Significant reductions in antiviral activity were also observed for 2′CMeA and 2′CMeC. Genotypic analysis by population sequencing of the resistant replicons revealed a single amino acid substitution, S282T, within the NS5B polymerase gene. No other mutations were detected.

TABLE 8.

Phenotypic analysis of GS-6620-resistant genotype 1b replicon cells

| Compounds | Wild-type EC50 (μM) | Fold resistancea |

|---|---|---|

| GS-6620 | 0.25 | 51 |

| 2′CMeA | 0.24 | >206 |

| 2′CMeC | 1.2 | >40 |

Fold resistance was calculated as the ratio of mutant replicon EC50 to the wild-type replicon EC50.

GS-6620 has high barrier to emergence of resistance in vitro.

Genotype 1b replicon cells were treated with either GS-6620, 2′-CMeA, HCV-796, or lomibuvir at 1×, 10×, or 15× EC50s. After 21 days of treatment, the cell culture plates were stained for the emergence of drug-resistant colonies. As shown in Fig. 6, GS-6620 completely suppressed the emergence of resistant colonies at 10× and 15× EC50, matching the results of 2′CMeA. In contrast, the NNIs, HCV-796, and lomibuvir permitted resistant colonies to emerge at both 10× and 15× EC50s, reflecting their lower resistance barriers.

FIG 6.

Nucleoside and nonnucleoside NS5B inhibitors show different barriers to resistance. Replicon cells were treated with various concentrations of 2′CMeA (NI), GS-6620 (NI), HCV-796 (NNI), and lomibuvir (NNI) for 21 days in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml of G-418. Culture medium was replaced with freshly prepared compound-containing medium every 3 days. At the end of 21-day culture, the medium was removed and the cells were fixed in 20% methanol solution and stained with crystal violet.

Effects of NS5B mutations S282T, M289L, and M289V on GS-441326 activity in biochemical assays.

To evaluate the impact of the S282T, M289L, and M289V mutations at the enzymatic level, the inhibitory activities of GS-441326 and the triphosphates of other NIs were tested against genotypes 1b and 2a recombinant NS5B polymerases carrying the S282T mutation, genotype 2a-specific mutations M289L, M289V, and the double mutation S282T/M289L (Table 9). Consistent with the resistance data from cell-based assays (Table 7), S282T NS5B showed 91- and 65-fold resistances to GS-441326 and 2′CMeATP, respectively. Either M289L or M289V alone conferred little resistance to GS-441326 or 2′CMeATP; however, the double mutation S282T/M289L increased the resistance 2-fold over S282T for GS-441326 and 4- to 6-fold for 2′CMeATP.

TABLE 9.

Fold resistance of mutant genotypes 1b and 2a NS5B polymerases against GS-441326, the active triphosphate of GS-6620

| Triphosphates | Fold resistance of mutations by genotypea: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT1b with S282T | GT2a with: |

||||

| S282T | M289L | M289V | S282T/M289L | ||

| GS-441326 | 240 | 91 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 470 |

| 2′CMeATP | 29 | 65 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 110 |

Fold resistance was calculated using the ratio of mutant NS5B IC50 to the wild-type NS5B IC50. The values are averages from at least three measurements.

Binding model of GS-441326 with HCV NS5B.

Based on an analysis of available X-ray crystal structures, sequences deposited in the European HCV database (33), and modeling of the elongating form of NS5B complex, all key residues that shape the polymerase active site are conserved across genotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 4a, and 5a. These residues include R48, K51, K155, R158, D220, T221, F224, D225, R280, S282, T287, N291, G317, D318, and D319. Further analysis of 793 sequences deposited in the European HCV database (including 209 1a and 425 1b genotypes) indicates that the two key residues forming the 1′ pocket are highly conserved (Fig. 7A). N291 is 100% conserved and T287 is 99.9% conserved, with one instance of S287 in genotype 1b. Additional residues that may influence the 1′ pocket are also highly conserved. G317 is 99.9% conserved and S282 is 99.5% conserved. The particular favorability of 1′-CN in this pocket is most likely due to a direct interaction with N291.

FIG 7.

Model of GS-441326 in the active site of elongating NS5B. (A) S282 and D225 are proposed to change conformation relative to apo structures, with S282 forming a hydrogen bond to the 2′-OH of the substrate or inhibitor. The 1′ pocket is formed by N291, T287, and G317 (not shown). (B) Positions of mutations selected using the genotype 2a infectious HCV. S282 is in direct contact with GS-441326, and the S282T mutation is likely to produce a steric clash with the 2′-C-Me of the inhibitor. M289 is not in direct contact with the inhibitor, and M289V/L mutations likely only subtly change the shape of the active site. Notably, this residue is not well conserved across genotypes.

With respect to resistance, based on the Norwalk virus (30) and poliovirus polymerase structures (29), we believe that residue S282 changes its conformation relative to its apo state when binding the substrate. Specifically, it flips into the active site after substrate binding to form a hydrogen bond with the substrate 2′-OH, whereas at the apo state, it is seen to form a hydrogen bond with V161. Concomitant with this conformational change, D225 flips out of the active site. The ribose is thus recognized by hydrogen bonds to 2′-OH through S282 and N291 and to 3′-OH through D225. In the case of the S282T mutation, this residue conformation puts the threonine methyl group in close proximity to the inhibitor 2′-C-methyl, conveying resistance.

The slight resistance observed with the M289V/L mutation is likely due to subtle shifts in positioning of the substrate in the pocket. The residue lies in proximity to the 1′ pocket but does not directly shape it (Fig. 7B). Notably, this residue is not well conserved across genotypes. It is M for genotypes 2a, 2b, 5a and 6a, C for genotypes 1a and 1b, and F for genotypes 3a and 4a.

DISCUSSION

GS-6620 is a nucleotide prodrug of a 1′-CN-2′-C-Me C-nucleoside analog and was the first adenosine analog tested clinically in HCV-infected patients (9). This study presents a detailed characterization of the pharmacology of GS-6620. GS-6620 was found to be a potent and highly selective HCV antiviral: (i) it showed potent pangenotype activities against HCV replicons and infectious virus, (ii) it is a specific antiviral against HCV when tested against a broad panel of RNA and DNA viruses, (iii) it showed minimal cytotoxicity in cell lines and primary cells, no inhibition of mitochondrial DNA content, no specific inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis, and no inhibition of host DNA or RNA polymerases at the highest concentration tested (200 to 500 μM), (iv) the NS5B S282T mutation was selected by GS-6620 in both GT2a infectious virus and GT1b replicon after approximately 60 days and 106 days of in vitro selection, and conferred resistance to GS-6620 in both cell-based and biochemical assays, and (v) GS-6620 demonstrated a high barrier to the emergence of resistance in vitro. In addition, a previous study showed GS-6620 had additive-to-synergistic effects in combination with other classes of direct antivirals, including NS5B NNIs, HCV NS 3/4A protease inhibitors and NS5A inhibitors (9).

2′CMeA was one of the earliest adenosine analogs reported with potent in vitro anti-HCV activity, but it is rapidly deactivated in vivo due to deamination by adenosine deaminase (34, 35). An adenosine deaminase-resistant analog 2′-C-Me-7-deazaA (MK-608) overcame the metabolic liability and produced an impressive 4.6-log10 reduction in HCV load after 37-day oral dosing in chimpanzees (36). However, MK-608 was not tested in HCV-infected human subjects. GS-6620 is a monophosphate prodrug of an adenosine deaminase-resistant C-nucleoside adenosine analog (GS-441285) that efficiently delivers a bioactive triphosphate (GS-441326) with similar intrinsic potency to that formed by MK608. Thus, it was hoped that potent antiviral activity would be observed for GS-6620 in clinical studies. The safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and anti-HCV activity of GS-6620 were assessed in genotype 1 treatment-naive subjects over 5 days in a first-in-human clinical study (37). While demonstrating the potential for potent antiviral activity (viral load reductions >4 logs in a few patients), high doses of up to 900 mg twice daily (BID) were required for efficacy, and substantial intra- and intersubject pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability was observed. The clinical findings with GS-6620 validated the findings of potent inhibition observed in vitro, but clinical efficacy appeared to be limited by the performance of the prodrug following oral administration in humans (32).

The nucleoside analog present in GS-6620 has a unique structural feature, including 1′-CN and a modified 4-aza-7,9-dideaza adenosine base. Biochemical assays clearly demonstrated that the active triphosphate GS-441326 is a potent competitive inhibitor for NS5B-catalyzed ATP incorporation, with activities similar to MK-608-TP and 12- to 14-fold more potent than 2′CMeATP (9). Also, like 2′CMeATP, the incorporated GS-441326 served as a chain terminator for RNA synthesis. All of these results suggest that neither 1′-CN modification nor the carbon substitution at the N9 position alters the base-pairing property or the substrate recognition at the NS5B active site.

The toxicity often associated with mitochondrial toxicity caused by inhibition of the mtDNA Pol γ or POLRMT has been reported for some nucleotide analogs (10, 38, 39). GS-6620 and its metabolites were extensively studied in both cell- and enzyme-based toxicity and off-target screening assays. GS-6620 showed minimal toxicity in multiple cell lines and primary cells. The only results suggesting some meaningful cytotoxicity potential was the observation of complex concentration-dependent effects on MT-4 cells and erythroid bone marrow progenitor cells. However, the effects on MT-4 cells, a T-cell line, did not correlate with the observation of toxicity in either stimulated or unstimulated PBMCs; therefore, these effects were deemed of low relevance to the toxicity potential of the compound. A key motivation for the selection of GS-6620 was the observation that the combination of 1′ and 2′ substitutions in the context of C-nucleoside base resulted in reduced incorporation by POLRMT (9). Consistent with the prior results showing a lack of incorporation by POLRMT, the results presented here illustrate that GS-441326 did not inhibit POLRMT in biochemical assays. In accord with the lack of effects of its active triphosphate on mtDNA Pol γ or POLRMT, GS-6620 was found to neither deplete mtDNA nor inhibit protein production of a mitochondrial gene product. Another potential off-target for a ribonucleotide analog RNA Pol II was also not inhibited. Consistent with the low potential for toxicity observed in vitro, the no-observed-adverse-effect levels (NOAEL) for GS-6620 were the highest doses tested following repeated oral administration for 26 weeks in rats and 39 weeks in dogs (1,000 and 60 mg/kg of body weight/day, respectively).

Cross-resistance studies using a panel of replicons encoding mutations selected by NS5B polymerase NIs and NNIs, NS3/4A protease inhibitors, and NS5A inhibitors showed that GS-6620 remained fully active against all of the mutations tested, with the exception of the NS5B S282T mutant. The resistance selection of GS-6620 yielded S282T in both genotype 2a infectious virus and genotype 1b replicon cells. No other mutations were detected in genotype 1b replicon cells. However, in genotype 2a virus, the mutation M289V or M289L emerged prior to the detection of S282T. Interestingly, the resistant viruses carrying both M289V and S282T mutations replicate efficiently at a level comparable to the wild-type virus but approximately 3-fold higher than the viruses carrying S282T alone, suggesting that mutations at residue M289 may function as a compensatory mutation to the S282T mutation. However, further studies are needed to determine the viral fitness of these resistance mutations individually or in combination. The amino acid at residue 289 is variable among different genotypes: C289 in genotypes 1a and 1b, M289 in genotypes 2a, 5a, and 6a, and F289 in genotypes 3a and 4a (33). M289V or M289L alone conferred low levels of resistance (average, 4.4-fold) to GS-6620 and slightly (<2-fold) augmented GS-6620 resistance when combined with S282T in 2a virus assays. Similarly, biochemical studies showed that genotype 2a NS5B carrying M289V or M289L mutations alone did not show a significant change in sensitivity to the inhibition by 2′-C-Me,1′-CN,4-aza-7,9-dideazaA-TP, but when combined with S282T, a 5-fold increase in resistance was observed for NS5B with the S282T/M289L double mutation. In addition, GS-6620 showed a high barrier to resistance, a key feature and advantage of HCV NIs over other classes of direct antivirals.

In conclusion, GS-6620 is a specific and potent HCV antiviral with pangenotype coverage. With its unique dual substitution at 1′-CN and 2′-C-Me, this novel C-nucleotide analog significantly enhanced the selectivity of the active triphosphate metabolite for the HCV NS5B polymerase over the host RNA polymerases. The pharmacology presented here translated into GS-6620 becoming the first adenosine analog to obtain clinical proof of concept, including the potential for potent anti-HCV activity. However, GS-6620 has not progressed further in clinical development due to the observation of unacceptably high variability and the poor oral pharmacokinetics of the prodrug in humans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brian Schultz, Roman Sakowicz, Christian Voitenleitner, and Uli Schmitz for their careful review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 January 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02351-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases 2009. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology 49:1335–1374. 10.1002/hep.22759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CL, Rice CM. 2011. Turning hepatitis C into a real virus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:307–327. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. 2012. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann. Intern. Med. 156:271–278. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson DR. 2011. The role of triple therapy with protease inhibitors in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 naïve patients. Liver Int. 31(Suppl 1):53–57. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown NA. 2009. Progress towards improving antiviral therapy for hepatitis C with hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitors. Part I: nucleoside analogues. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 18:709–725. 10.1517/13543780902854194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sofia MJ. 2011. Nucleotide prodrugs for HCV therapy. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 22:23–49. 10.3851/IMP1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, Shiffman ML, Lawitz E, Everson G, Bennett M, Schiff E, Al-Assi MT, Subramanian GM, An D, Lin M, McNally J, Brainard D, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Patel K, Feld J, Pianko S, Nelson DR. 2013. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:1867–1877. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins WJ, Ray AS, Chong LS. 2010. HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 13:441–465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho A, Zhang L, Xu J, Lee R, Butler T, Metobo S, Aktoudianakis V, Lew W, Ye H, Clarke M, Doerffler E, Byun D, Wang T, Babusis D, Carey AC, German P, Sauer D, Zhong W, Rossi S, Fenaux M, McHutchison JG, Perry J, Feng J, Ray AS, Kim CU. 2 April 2013. Discovery of the first C-nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitor (GS-6620) with demonstrated antiviral response in HCV infected patients. J. Med. Chem. 10.1021/jm400201a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold JJ, Sharma SD, Feng JY, Ray AS, Smidansky ED, Kireeva ML, Cho A, Perry J, Vela JE, Park Y, Xu Y, Tian Y, Babusis D, Barauskus O, Peterson BR, Gnatt A, Kashlev M, Zhong W, Cameron CE. 2012. Sensitivity of mitochondrial transcription and resistance of RNA polymerase II dependent nuclear transcription to antiviral ribonucleosides. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003030. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung M, Gibbs CS, Tsiang M. 2002. Biochemical characterization of rhinovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral Res. 56:99–114. 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung M, Wang R, Liu X. 2011. Preparation of HCV NS3 and NS5B proteins to support small-molecule drug discovery. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. Chapter 13:Unit13B.16. 10.1002/0471141755.ph13b06s54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson AA, Tsai Y, Graves SW, Johnson KA. 2000. Human mitochondrial DNA polymerase holoenzyme: reconstitution and characterization. Biochemistry 39:1702–1708. 10.1021/bi992104w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves SW, Johnson AA, Johnson KA. 1998. Expression, purification, and initial kinetic characterization of the large subunit of the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Biochemistry 37:6050–6058. 10.1021/bi972685u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson M, Yang H, Sun SC, Peng B, Tian Y, Pagratis N, Greenstein AE, Delaney WE., IV 2010. Novel hepatitis C virus reporter replicon cell lines enable efficient antiviral screening against genotype 1a. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3099–3106. 10.1128/AAC.00289-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohmann V, Körner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110–113. 10.1126/science.285.5424.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G, Chan K, Yang H, Corsa A, Pokrovskii M, Paulson M, Bahador G, Zhong W, Delaney W., IV 2011. Selection of clinically relevant protease inhibitor-resistant viruses using the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus infection system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2197–2205. 10.1128/AAC.01382-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu M, Corsa AC, Xu S, Peng B, Gong R, Lee YJ, Chan K, Mo H, Delaney W, IV, Cheng G. 2013. In vitro efficacy of approved and experimental antivirals against novel genotype 3 hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons. Antiviral Res. 100:439–445. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng B, Yu M, Xu S, Lee YJ, Tian Y, Yang H, Chan K, Mo H, McHutchison J, Delaney W, IV, Cheng G. 2013. Development of robust hepatitis C virus genotype 4 subgenomic replicons. Gastroenterology 144:59–61. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herlihy KJ, Graham JP, Kumpf R, Patick AK, Duggal R, Shi ST. 2008. Development of intergenotypic chimeric replicons to determine the broad-spectrum antiviral activities of hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3523–3531. 10.1128/AAC.00533-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong KA, Xu S, Martin R, Miller MD, Mo H. 2012. Tegobuvir (GS-9190) potency against HCV chimeric replicons derived from consensus NS5B sequences from genotypes 2b, 3a, 4a, 5a, and 6a. Virology 429:57–62. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pokrovskii MV, Bush CO, Beran RK, Robinson MF, Cheng G, Tirunagari N, Fenaux M, Greenstein AE, Zhong W, Delaney WE, IV, Paulson MS. 2011. Novel mutations in a tissue culture-adapted hepatitis C virus strain improve infectious-virus stability and markedly enhance infection kinetics. J. Virol. 85:3978–3985. 10.1128/JVI.01760-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenaux M, Eng S, Leavitt SA, Lee YJ, Mabery EM, Tian Y, Byun D, Canales E, Clarke MO, Doerffler E, Lazerwith SE, Lew W, Liu Q, Mertzman M, Morganelli P, Xu L, Ye H, Zhang J, Matles M, Murray BP, Mwangi J, Zhang J, Hashash A, Krawczyk SH, Bidgood AM, Appleby TC, Watkins WJ. 2013. Preclinical characterization of GS-9669, a thumb site II inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:804–810. 10.1128/AAC.02052-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Y, Curtis M, Borroto-Esoda K. 2011. HBV DNA replication mediated by cloned patient HBV reverse transcriptase genes from HBV genotypes A-H and its use in antiviral phenotyping assays. J. Virol. Methods 173:340–346. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkus G, Hitchcock MJM, Cihlar T. 2002. Assessment of mitochondrial toxicity in human cells treated with tenofovir: comparison with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:716–723. 10.1128/AAC.46.3.716-723.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copeland RA. 2000. Chapter 8: reversible inhibitors, p 266–304 In Enzymes: a practical introduction to structure, mechanism, and data analysis, 2nd ed. Wiley-VCH, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lodeiro MF, Uchida AU, Arnold JJ, Reynolds SL, Moustafa IM, Cameron CE. 2010. Identification of multiple rate-limiting steps during the human mitochondrial transcription cycle in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 285:16387–16402. 10.1074/jbc.M109.092676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosley RT, Edwards TE, Murakami E, Lam AM, Grice RL, Du J, Sofia MJ, Furman PA, Otto MJ. 2012. Structure of hepatitis C virus polymerase in complex with primer-template RNA. J. Virol. 86:6503–6511. 10.1128/JVI.00386-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong P, Peersen OB. 2010. Structural basis for active site closure by the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:22505–22510. 10.1073/pnas.1007626107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamyatkin DF, Parra F, Alonso JM, Harki DA, Peterson BR, Grochulski P, Ng KK. 2008. Structural insights into mechanisms of catalysis and inhibition in Norwalk virus polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 283:7705–7712. 10.1074/jbc.M709563200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, Muerhoff AS, Rice CM, Stapleton JT, Simmonds P. 2013. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and assignment web resource. Hepatology 59:318–327. 10.1002/hep.26744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami E, Wang T, Babusis D, Lepist EI, Sauer D, Park Y, Vela JE, Shih R, Birkus G, Stefanidis D, Kim CU, Cho A, Ray AS. 2014. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of the anti-hepatitis C virus nucleotide prodrug GS-6620. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58:1943–1951. 10.1128/AAC.02350-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Combet C, Garnier N, Charavay C, Grando D, Crisan D, Lopez J, Dehne-Garcia A, Geourjon C, Bettler E, Hulo C, Le Mercier P, Bartenschlager R, Diepolder H, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM, Rice CM, Trépo C, Penin F, Deléage G. 2007. euHCVdb: the European hepatitis C virus database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D363–D366. 10.1093/nar/gkl970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll SS, Tomassini JE, Bosserman M, Getty K, Stahlhut MW, Eldrup AB, Bhat B, Hall D, Simcoe AL, LaFemina R, Rutkowski CA, Wolanski B, Yang Z, Migliaccio G, De Francesco R, Kuo LC, MacCoss M, Olsen DB. 2003. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by 2′-modified nucleoside analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11979–11984. 10.1074/jbc.M210914200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen DB, Eldrup AB, Bartholomew L, Bhat B, Bosserman MR, Ceccacci A, Colwell LF, Fay JF, Flores OA, Getty KL, Grobler JA, LaFemina RL, Markel EJ, Migliaccio G, Prhavc M, Stahlhut MW, Tomassini JE, MacCoss M, Hazuda DJ, Carroll SS. 2004. A 7-deaza-adenosine analog is a potent and selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication with excellent pharmacokinetic properties. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3944–3953. 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3944-3953.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]