Abstract

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei. New drugs are needed to treat HAT because of undesirable side effects and difficulties in the administration of the antiquated drugs that are currently used. In human proliferative diseases, protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) inhibitors (PTKIs) have been developed into drugs (e.g., lapatinib and erlotinib) by optimization of a 4-anilinoquinazoline scaffold. Two sets of facts raise a possibility that drugs targeted against human PTKs could be “hits” for antitrypanosomal lead discoveries. First, trypanosome protein kinases bind some drugs, namely, lapatinib, CI-1033, and AEE788. Second, the pan-PTK inhibitor tyrphostin A47 blocks the endocytosis of transferrin and inhibits trypanosome replication. Following up on these concepts, we performed a focused screen of various PTKI drugs as possible antitrypanosomal hits. Lapatinib, CI-1033, erlotinib, axitinib, sunitinib, PKI-166, and AEE788 inhibited the replication of bloodstream T. brucei, with a 50% growth inhibitory concentration (GI50) between 1.3 μM and 2.5 μM. Imatinib had no effect (i.e., GI50 > 10 μM). To discover leads among the drugs, a mouse model of HAT was used in a proof-of-concept study. Orally administered lapatinib reduced parasitemia, extended the survival of all treated mice, and cured the trypanosomal infection in 25% of the mice. CI-1033 and AEE788 reduced parasitemia and extended the survival of the infected mice. On the strength of these data and noting their oral bioavailabilities, we propose that the 4-anilinoquinazoline and pyrrolopyrimidine scaffolds of lapatinib, CI-1033, and AEE788 are worth optimizing against T. brucei in medicinal chemistry campaigns (i.e., scaffold repurposing) to discover new drugs against HAT.

INTRODUCTION

Millions of people are at risk of contracting human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), a disease that is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei. Current chemotherapies cannot be administered orally, and some are toxic (1). Consequently, a pressing need exists for new therapeutics with oral bioavailability and adequate safety profiles (2).

The rational design of drugs to inhibit the function of proteins that are essential for cell viability has an important place in the hunt for new antitrypanosomal pharmaceutics (3–5). Investigators who suspect that a protein is “druggable” face numerous challenges throughout the course of drug design and development (6–8). First, genetics must be used to validate the candidate protein as a bona fide drug target (4, 8). Second, small-molecule inhibitors of the protein target must be identified. Third, the inhibitors must be selectively toxic to parasitic cells. Fourth, the inhibitor structure must be optimized reiteratively in a medicinal chemistry campaign to identify compounds with the best balance of potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties. Fifth, a human safety trial (phase I) must be conducted to determine whether the chemical entity can become a drug, followed by phase II studies involving patients with the disease. Unfortunately, most genetically validated putative parasite drug targets have failed to produce drugs because (i) small-molecule inhibitors of the druggable target have not been found and/or (ii) the inhibitors are not sufficiently potent or lack favorable pharmacokinetic properties (see reference 8 for a review). Given its track record over the last 3 decades (reviewed in reference 9), alternative approaches are needed to complement rational discovery of drugs for HAT.

In “piggyback” drug discovery (reviewed in reference 10), a drug that is used for one ailment can be adopted directly for the treatment of a parasitic disease. In the case of neglected tropical diseases, such as human African trypanosomiasis, piggybacking is a logical path to find new drugs because the field is severely underfunded for commercial reasons. Unfortunately, drugs in clinical use are not optimized against parasitic targets; therefore, medicines that can work well against both human disease and parasites are rare.

Scaffold repurposing (10–12) can enhance the piggyback approach for neglected-disease drug discovery. We advocate scaffold repurposing because it has a better chance of creating new drugs that are more selective and/or potent against trypanosomes. The success of the strategy rests on finding compounds that (i) (preferably) have gone through phase I clinical trials and (ii) are orally bioavailable. A select group of such compounds can be tested to find out whether they inhibit the replication of bloodstream T. brucei in vitro and are efficacious in an animal model of HAT. Scaffolds of such drugs can then be repurposed in a medicinal chemistry initiative and are likely to yield novel antitrypanosomal compounds.

In chronic human proliferative diseases, studies of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) have been a fertile ground for the development of new drugs (e.g., lapatinib, erlotinib, imatinib, and gefitinib) (reviewed in reference 13). Most of the drug discovery programs have used anilinoquinazoline, anilinoquinoline, and anilinopyridopyrimidine scaffolds (reviewed in references 14 and 15). The chemical entities of these drugs present a splendid opportunity for scaffold repurposing in antitrypanosomal drug discovery.

Our choice of Tyr kinase pathways as a target for hit discovery in the African trypanosome is rooted in six observations. First, a BLAST (16) analysis of protein kinases in the trypanosomal genome using the kinase domain of human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) as a query revealed that EGFR-like enzymes that lack the extracellular ligand-binding region of EGFR were present (data not shown). Second, a pharmacological test of the bioinformatic predictions was performed with the 4-anilinoquinazolines AG1478 (17, 18), erlotinib (19), and lapatinib (20, 21). AG1478 killed cultured bloodstream trypanosomes, with a 50% growth inhibitory concentration (GI50) of 5 μM (data not presented), and lapatinib killed T. brucei, with a GI50 of 1.5 μM (22). Third, PTK inhibitors (PTKIs) affect multiple aspects of T. brucei biology. For example, tyrphostin A47 blocks the endocytosis of transferrin, which is needed for the uptake of iron by T. brucei (23, 24). Fourth, PTKI drugs are orally bioavailable and well tolerated in chronic disease patients who must take them for protracted periods, compared to the length of antibiotic treatments. For use against HAT, patients will take the drug for a relatively short time (∼10 days), so we are in a better position to minimize undesirable side effects of the drugs. Fifth, the synthesis of the compounds (e.g., lapatinib and CI-1033) is published (see references 20, 25–27), lending this class of drugs to rapid medicinal chemistry scaffold repurposing for HAT. Finally, four pharmaceutical companies, namely, Pfizer, Novartis, Genentech, and GlaxoSmithKline, generously provided us with sufficient amounts of drugs to initiate our experiments.

The PTKI drugs lapatinib (GlaxoSmithKline), CI-1033 (Pfizer), axitinib (Pfizer), sunitinib (Pfizer), PKI-166 (Novartis), erlotinib (Genentech), and AEE788 (Novartis) inhibited the replication of cultured bloodstream T. brucei at low micromolar concentrations. In a mouse model of HAT, orally administered lapatinib controlled parasitemia, and the drug cured infection in 25% of mice. In this proof-of-concept study CI-1033 and AEE788 improved the mean survival of infected mice without curing the disease. These observations bode well for attempts to optimize 4-anilinoquinazoline or pyrrolopyrimidine scaffolds as leads for antitrypanosomal drug discovery (28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone and polyethylene glycol 300 were from Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich). The components of HMI-9 medium were previously described by Hirumi and Hirumi (29).

Drugs.

The drugs used were gifts from the pharmaceutical companies indicated: Lapatinib (GlaxoSmithKline), CI-1033 (Pfizer), sunitinib (Pfizer), axitinib (Pfizer), erlotinib (Genentech), imatinib (Novartis), PKI-166 (Novartis), and AEE788 (Novartis).

All compounds were dissolved in DMSO as 10 mM stocks and stored at −20°C in small aliquots in order to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. The final concentration of DMSO in all in vitro cell culture experiments was <0.5%.

For studies with mice, the compounds were reconstituted in two different solvents based on the route of administration: (i) DMSO for intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration or (ii) water (CI-1033) or N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone and polyethylene glycol 300 (1:9 [vol/vol]) (lapatinib and AEE788) for oral dosing. The drugs were prepared fresh daily and the concentration was adjusted so that each mouse received <200 μl of solvent/dosing.

Axenic trypanosomal culture.

Bloodstream T. brucei brucei CA427 strain (from C. C. Wang, University of California San Francisco [UCSF], CA) was used for both in vitro and in vivo experiments. The parasites were cultured in HMI-9 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% Serum Plus (heat inactivated), and an antibiotic-antimycotic solution with a final concentration of 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) (29). The culture was maintained in log growth phase (density < 106/ml) under standard conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C) and was subcultured every 1 to 2 days by seeding trypanosomes at 104/ml or 103/ml, respectively.

Trypanosomal replication and drug susceptibility assays in vitro.

The drugs were tested initially at 400 nM or 4 μM to define the range of concentrations for subsequent assays. T. brucei cells from a mid-log-phase culture were diluted into prewarmed HMI-9 medium (1 ml) at 2 × 103 cells/ml in each well of the 24-well plates. DMSO or drugs (in 2 μl) were added from the appropriate working solutions to the specified final concentrations. After 48 h of incubation, cell density was determined with a hemocytometer. Cell density as a function of drug concentration was plotted with Excel (Microsoft), and the GI50 for each drug was calculated using the equation of the trend line from the data. The standard deviations reported were from a total of four separate measurements obtained from two independent experiments.

Short-term 6-h drug exposure for trypanosomal killing assays.

Stocks of drugs, with the exception of pentamidine, were prepared in DMSO; pentamidine was prepared in sterile distilled water. One milliliter of T. brucei (1 × 105 cells/ml) was aliquoted into 24-well plates and 1 μl of drug solution added, to a final concentration of 5 μM. An equal volume of DMSO or water was added to the control samples. Following incubation for 6 h (5% CO2 at 37°C), the cell suspensions were concentrated 10-fold by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature), followed by the removal of all but 100 μl of supernatant. Trypanosomal density was determined either with a hemocytometer or in a Z2 Coulter counter (Beckman) with AccuComp software (settings: range, 2.5 μm to 5 μm; dilution factor, 50; metered volume, 1 ml) in duplicate. The results presented were obtained from two independent experiments, each sample of which was performed in duplicate.

Trypanosomal replication for 48 h after 6 h of drug exposure.

The drug-treated cells (above) were washed twice with 900 μl HMI-9 medium, leaving approximately 100 μl of supernatant each time. The trypanosomes were resuspended at 1 × 104 cells/ml (1 ml) in 24-well plates and incubated for 48 h at 37°C under 5% CO2, after which the cell density was determined.

HeLa culture and drug susceptibility assays.

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Cellgro) containing 10% FBS and an antibiotic-antimycotic combination (100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B [22]). The cultures were maintained at up to 70% confluence in 25-cm2 culture flasks (Corning) at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

For drug testing, HeLa cells were diluted into prewarmed DMEM at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml and distributed into 24-well plates (1 ml per well), followed by 24 h of incubation. DMSO or drugs (5 μl) were added from appropriate working solutions to the specified final concentrations, and the cells were cultured for 48 h. Each well was washed with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 100 μl of trypsin-EDTA solution (Gibco) for 3 min at 37°C under 5% CO2. DMEM (900 μl) was added to each well and mixed, and the unadhered cells were retrieved into 1.5-ml polypropylene tubes. The cells (in 45-μl aliquots) were mixed with 5 μl trypan blue (0.04%) (Gibco), and the cell density was determined with a hemocytometer. The GI50 of each drug was calculated by plotting data for the cell counts in Excel (Microsoft), as described above. The standard deviations reported are from a total of four separate measurements obtained from two independent experiments.

Mice.

Swiss Webster (female) mice, age 8 to 10 weeks, were purchased from Harlan Laboratories and housed in a microisolator, with four animals per group under standard conditions. The animals were infected following an acclimatization period of 7 days. All experiments were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Georgia, Athens. The mice were checked at least twice daily during the course of an experiment.

Drug efficacy in a mouse model of acute human African trypanosomiasis.

Logarithmic-phase T. brucei CA427 were rinsed twice in bicine-buffered saline containing glucose (BSG) (50 mM bicine, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, and 1% [wt/vol] glucose [pH 7.4]), pelleted (3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C), and resuspended at 104 cells/ml in BSG. Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with 103 trypanosomes (day 0). The mice were randomly assigned to different groups (four mice per group). Drug treatment was initiated 1 day postinfection and continued for 14 days. The control mice received the vehicle. The animals in the treatment groups were administered drugs as follows based on their daily body weight, either orally or intraperitoneally (i.p.): 100 mg/kg of body weight lapatinib every 12 h, 30 mg/kg CI-1033 every 24 h, and 30 mg/kg AEE788 every 24 h. Parasitemia was monitored daily for 14 days by collecting 2 μl of blood (via tail prick) into 18 μl of 0.85% ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and counting the parasites with a hemocytometer. When parasitemia was >107/ml, dilutions of blood were made into BSG. If no parasite was detected after 14 days, parasitemia was monitored three times a week for 30 days. Mice surviving 30 days after the death of the last control mouse and having no parasitemia were considered cured. The data were plotted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Tyrosine kinase drugs reduce replication of cultured bloodstream trypanosomes.

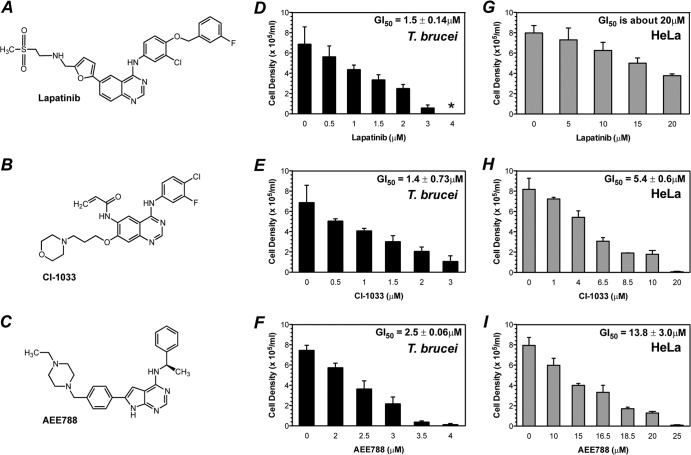

The tyrosine kinase inhibitors tyrphostin A47 and lapatinib inhibit the replication of T. brucei (22, 23). We extended these observations by testing seven other PTKI drugs in growth inhibition assays. For lapatinib, the trypanosomal GI50 (i.e., drug concentration that inhibits T. brucei replication by 50%) was 1.5 μM (22). Three PTKIs, CI-1033 (30), PKI-166 (31, 32), and sunitinib (33, 34), also inhibited the replication of bloodstream T. brucei, with GI50s of 1.3 μM or 1.4 μM. Erlotinib (19), axitinib (35), and AEE788 (25) had GI50s of 1.9 μM, 2.0 μM, and 2.5 μM, respectively. Imatinib (Gleevec) (36, 37) was relatively inactive (i.e., GI50 > 10 μM) (Table 1 and Fig. 1F and G). Of these drugs, CI-1033, AEE788, and lapatinib became the focus of this study because their plasma concentrations after oral administration to mice were known in the literature to equal or exceed the GI50 in vitro. The general cytotoxicity of the compounds was tested by exposing a human HeLa cell line to the drugs for 48 h (Fig. 1G to I). Lapatinib, with a GI50 against HeLa cells (i.e., GI50HeLa) of >20 μM, was the least toxic (Fig. 1G), followed by AEE788 (GI50HeLa, 13.8 μM) (Fig. 1I) and CI-1033 (GI50HeLa, 5.4 μM) (Fig. 1H).

TABLE 1.

Effect of tyrosine kinase drugs on replication of bloodstream T. brucei

| Drug | GI50 (mean ± SD) (μM) | Major target protein kinase(s) in humansa |

|---|---|---|

| CI-1033 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | EGFR |

| Erlotinib | 1.9 ± 0.1 | EGFR |

| PKI-166 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | EGFR |

| Lapatinib | 1.5 ± 0.1 | HER2 |

| AEE788 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | EGFR, VEGFR |

| Axitinib | 2.0 ± 0.5 | VEGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit |

| Sunitinib | 1.3 ± 0.1 | VEGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit, Flt-3 |

| Imatinib | >10.0 | c-Abl, PDGFR, c-Kit, c-Src |

VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

FIG 1.

Lapatinib, CI-1033, and AEE788 inhibit T. brucei replication in vitro over 48 h exposure. (A to C) Chemical structures of lapatinib, CI-1033, and AEE788. (D to F) Drug inhibition of trypanosome replication. Bloodstream T. brucei (2 × 103 cells/ml) were cultured in 24-well plates for 48 h with either DMSO (0 μM control) or different concentrations of drug. *, no cells observed. (G to I) Effects of drugs on human HeLa cell replication. HeLa cells (1 × 105 cells/ml) were cultured in 24-well plates for 24 h and incubated for 48 h with either DMSO (0 μM control) or different concentrations of drug. The cell densities of trypanosomes and HeLa cells were determined with a hemocytometer after 48 h. (D to I) The mean cell density ± standard deviation values are presented.

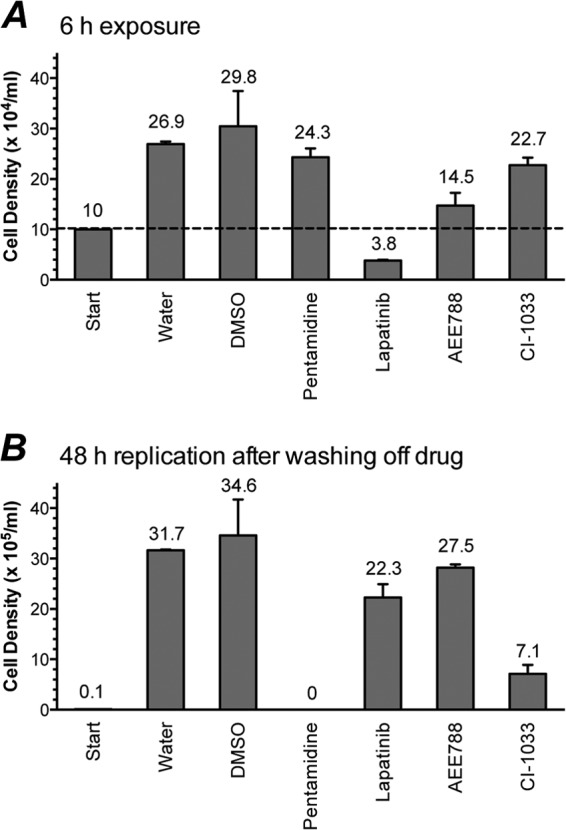

We were interested in learning the contribution of cell death to overall replication inhibition (Fig. 1D to F and Table 1). To investigate this topic, trypanosomes (105/ml) were exposed to select PTKI drugs (5 μM) for 6 h (the cell division time of cultured bloodstream T. brucei), and the cell density was determined (Fig. 2A). Two kinds of effects were observed: cell killing and reduced replication. For lapatinib, the density of the treated cells was 62% less than the starting level, so this drug kills trypanosomes within 6 h. In the case of AEE788, CI-1033, and pentamidine, the densities of the treated cultures after 6 h exceeded the starting densities; hence, these drugs did not kill within 6 h. However, all three drugs reduced the replication of T. brucei: trypanosomal density after 6 h was reduced by 51% (AEE788), 24% (CI-1033), and 10% (pentamidine) compared to the control (untreated cells) (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Effects of 6-h drug exposure on trypanosomal survival and replication. The mean cell density ± standard deviation values are presented. (A) Cell density after 6 h drug treatment. Dashed line indicates starting trypanosome density prior to 6-h drug treatment. (B) Cell density after 48 h recovery following 6 h drug exposure. Trypanosomes (1 × 105 cells/ml) were treated with drug (5 μM) or vehicle (DMSO or water) for 6 h. The cells were washed twice with HMI-9 medium, resuspended at 1 × 104 cells/ml, and cultured for 48 h. Trypanosomal densities were determined with a hemocytometer or a Z2 Coulter counter at 0 h (start) and following 6-h and 48-h incubations.

Anticipating that the effects of some drugs on T. brucei might manifest well after exposure to the compounds, we monitored trypanosomal replication 48 h after the drugs were washed off and the cells were seeded at the same density (104/ml) (Fig. 2B). Pentamidine was the most potent compound in this delayed-killing assay: no trypanosomes were detected after 48 h, whereas control (untreated) cells replicated to a density of 3 × 106/ml under similar conditions. CI-1033 killed 79% of trypanosomes in this assay, while AEE788 and lapatinib killed 21% and 36% of the parasites, respectively (Fig. 2B).

We infer from these data (Fig. 2) that despite the similarity of the GI50 values of lapatinib, AEE788, and CI-1033 (Table 1), lapatinib is the most promising of three because it can kill trypanosomes after a short period (Fig. 2A). We envision that drugs that kill trypanosomes after a short exposure time are likely to be more effective in an animal model of the disease in which the drug is bound to be cleared from the blood with time. These ideas were tested in a mouse model of HAT (Fig. 3 to 5).

FIG 3.

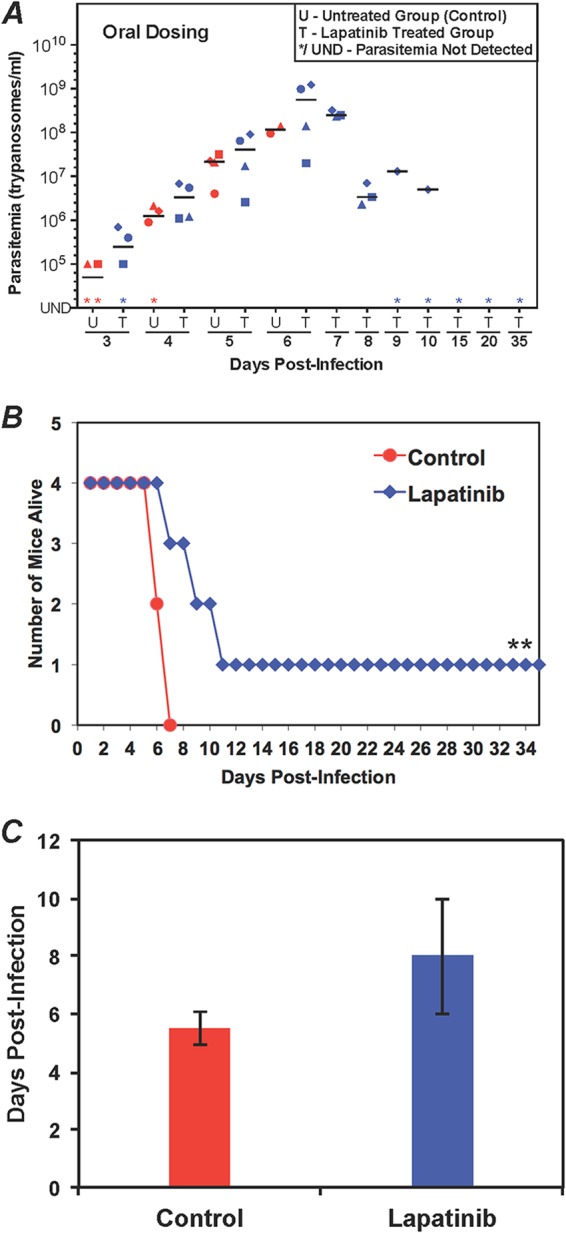

Evaluation of lapatinib in the mouse model of acute HAT. (A) Parasitemia during lapatinib treatment. Mice (four per group) were infected with 103 T. brucei CA427 (day 0). After 24 h, lapatinib (100 mg/kg) was administered by oral gavage twice daily (every 12 h). The control mice received vehicle. Parasitemia was determined every 24 h. U, untreated group; T, treated group. Different shapes represent individual mice. The horizontal lines in each group indicate median parasitemia levels. (B) Animal survival postinfection for control and lapatinib-treated mice. **, a mouse was cured. (C) Mean survival of mice. The average number of days that a treated animal survived (cured mice were not included) and the standard deviation values are shown here.

FIG 5.

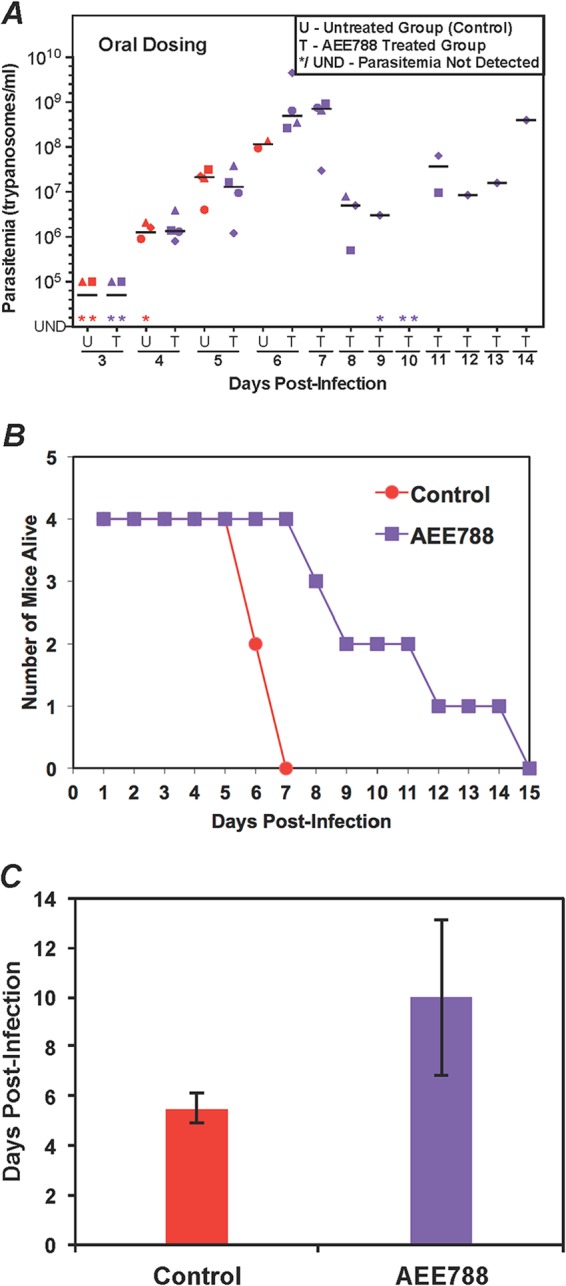

Evaluation of AEE788 in the mouse model of acute HAT. (A) Parasitemia during AEE788 treatment. Mice (four per group) were infected with 103 T. brucei CA427 (day 0). After 24 h, AEE788 (30 mg/kg) was administered by oral gavage once daily. The control mice received vehicle. Parasitemia was determined every 24 h. U, untreated group; T, treated group. Different shapes represent individual mice. The horizontal lines in each group indicate median parasitemia. (B) Animal survival postinfection for control and AEE788-treated mice. (C) Mean survival of mice. The average survival days ± standard deviation values are plotted.

Efficacy of PTKI drugs in a mouse model of HAT.

We followed up the in vitro work with cultured trypanosomes (Fig. 1D to F, Fig. 2, and Table 1) by trying to identify drugs with efficacy in a mouse model of HAT (i.e., “leads”) (38). The drugs for this study were chosen if their concentrations in plasma after oral administration were documented in the literature as being equal to or exceeding the GI50 in vitro (Table 1). For example, plasma concentrations of the 4-anilinoquinazolines (e.g., lapatinib, erlotinib, and CI-1033) reached 4 μM (39–42), whereas the GI50 for the drugs against T. brucei is <2 μM (Fig. 1D to F and Table 1). This fact suggested that the drugs might control a T. brucei infection without necessarily eliminating the parasites from a mouse, because the plasma level of the drug was <10× GI50. Nevertheless, for proof of principle, the study was warranted, because we also tracked parasites in mouse blood (i.e., parasitemia) as a measure of drug efficacy, even if a cure was elusive.

The drugs were administered either orally or intraperitoneally using doses employed in murine models of proliferative disease (25, 30, 43–45) (see Materials and Methods).

In untreated mice, trypanosomes were usually detected in the blood on day 2 postinfection, and parasitemia peaked between days 5 and 7 at 108/ml or 109/ml. The untreated mice did not control the parasitemia and succumbed to the disease, with a mean survival time of about 5 days (Fig. 3C, 4C, and 5C).

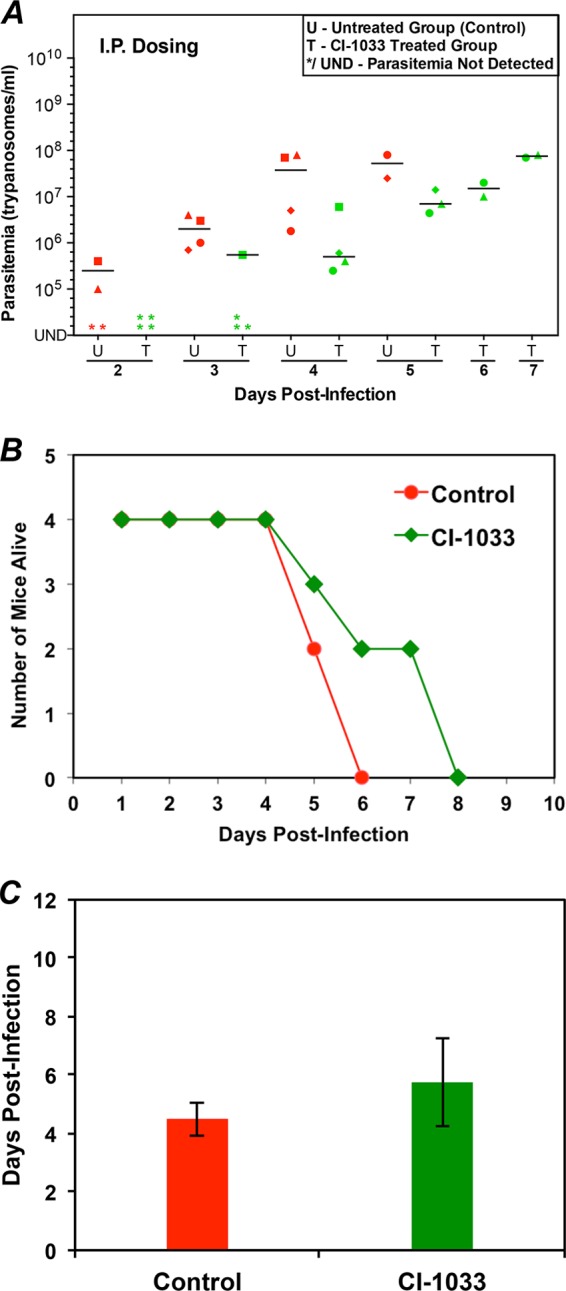

FIG 4.

Evaluation of CI-1033 in the mouse model of acute HAT. (A) Parasitemia during CI-1033 treatment. Mice (four per group) were infected with 103 T. brucei CA427 (day 0). After 24 h, CI-1033 (30 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) once daily. The control mice received vehicle. Parasitemia was determined every 24 h. U, untreated group; T, treated group. Different shapes represent individual mice. The horizontal lines in each group indicate median parasitemia levels. (B) Animal survival postinfection for control and CI-1033-treated mice. (C) Mean survival of mice. The average survival days ± standard deviation values are plotted.

When lapatinib was administered orally, three effects on trypanosomes in blood were observed. First, whereas the control mice died after parasitemia reached 108/ml, lapatinib-treated mice were alive with parasitemia with levels of >108/ml on day 6 (Fig. 3A). Second, on day 7, when all the control mice were dead, three of the lapatinib-treated mice were alive. Third, in the surviving mice, the parasitemia levels dropped 150-fold, from an average of 6 × 108/ml on day 6 to 4 × 106/ml on day 8 (Fig. 3A). Lapatinib cured 25% of trypanosome-infected mice (Fig. 3B) in three independent studies, each with 4 mice. The mean survival of the mice (excluding those that were cured) was 8 days (Fig. 3C), instead of 5.5 days for control mice that were not treated with a drug. The dosing route for lapatinib influenced the efficacy of the drug. Intraperitoneal administration of lapatinib delayed the onset of parasitemia (data not shown). However, that treatment regimen did not eliminate the infection, and all drug-treated mice died by day 8. Thus, the oral dosing of lapatinib was superior to delivery by intraperitoneal injection for controlling T. brucei infection in mice.

CI-1033 had a modest effect on trypanosomes in the blood of infected mice (Fig. 4). The drug reduced the number of trypanosomes in the blood by 20-fold on day 4 (compare the mean parasitemia of 4 × 107/ml in untreated mice to 2 × 106/ml in drug-treated mice; Fig. 4A). On day 6, when all the control mice had died, two of the CI-1033-treated mice were alive, but all of them died in the next 2 days (Fig. 4B). The mean survival of the mice was 5.8 days, compared to 4.5 days for the untreated mice (Fig. 4B and C). The oral administration of CI-1033 produced similar results (data not shown).

Orally administered AEE788 controlled T. brucei infection in mice (Fig. 5). On day 7, when none of the control mice were alive, every AEE788-treated mouse survived (Fig. 5A and B). Drug treatment reduced parasitemia 100-fold, from 109/ml on day 7 to 107/ml on day 8 (Fig. 5A). The mean survival of AEE788-treated mice increased to 10 days from 5.5 days for the untreated mice (Fig. 5B and C). When the drug was administered intraperitoneally, parasitemia was reduced initially, but the mice died with low levels of parasitemia, and their mean survival time was similar to that of untreated mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

New hits from a focused screen of PTKI drugs: lead discovery for HAT.

Only a few drugs, none of which are administered orally, are used for treating human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) (reviewed in references 9 and 46). Due to the high cost of discovering new drugs (47) and the reality that the field is underfunded because pharmaceutical companies do not consider drug discovery for diseases of poverty profitable, a piggyback drug discovery strategy of using existing drug scaffolds as the template for synthesizing new leads against trypanosomes has been advocated (10, 11, 22, 28, 48). One path to reducing the total cost of identifying new chemical entities for antitrypanosomal drug discovery is to perform an initial focused screen, where the search for novel antitrypanosomal scaffolds is guided by the basic biology of the trypanosome (see reference 49 for a perspective).

Studies of the physiological pathways in the trypanosome can guide the discovery of new chemical entities (23, 24, 38, 50). For example, T. brucei needs iron for viability, and it acquires the metal by the endocytosis of transferrin (Tf), to which iron is bound, from its vertebrate host (51). From this information, one would project that the inhibition of the uptake of Tf is detrimental to the survival of the disease-causing bloodstream-form trypanosome. We discovered that endocytic uptake of Tf in the trypanosome is stimulated by diacylglycerol (DAG) (24). In attempts to understand the pathway linking DAG and Tf uptake, we tested the effect of inhibitors of Ser/Thr protein kinases (e.g., protein kinase C [PKC]) or PTKs on DAG-stimulated endocytosis of Tf, because in mammalian systems, most DAG signaling is mediated by PKC (52). Unexpectedly, DAG-stimulated endocytosis of Tf was not blocked by a PKC inhibitor, and indeed, the genome of T. brucei does not encode a classic PKC. Instead, our pharmacological studies indicated that a protein Tyr kinase inhibitor, tyrphostin A47, inhibited DAG-stimulated endocytosis of Tf (23).

We leveraged this basic biological observation (above) for lead discovery by mining the literature for drugs that target PTKs in humans (reviewed in references 13 and 53) as possible hits for antitrypanosomal drug discovery. This approach enables a focused screen using only several small molecules (i.e., <10) instead of thousands of small molecules needed for high-throughput initiatives. Remarkably, the hit discovery rate with the focused screen strategy (stage 1) was very high: 7 out of 8 molecules examined were active (Table 1), emphatically validating our approach. We emphasize that we are not advocating that the hits be used directly to treat HAT. Rather, in stage 2 of this plan (lead discovery), we tested whether the hits could, when administered orally, control trypanosomal replication in a mouse model of HAT. If results from this stage 2 were positive, the justification for a medicinal chemistry campaign (stage 3, scaffold optimization for HAT) to synthesize new derivatives for antitrypanosomal lead optimization is strengthened.

In a proof-of-principle study using a mouse model of HAT (i.e., stage 2, lead discovery of our scaffold repurposing blueprint), three measures were used to assess whether or not the hits (Table 1) were potential leads against the disease. First, did the drug protect mice from death when all untreated control mice died? Second, did the drug cause a reduction in parasitemia, since untreated mice cannot control parasitemia at any stage of the infection? Finally, does the drug cure a trypanosomal infection in mice?

Lapatinib passed all 3 tests: it reduced the number of trypanosomes in the mouse (Fig. 3) and cured 25% of trypanosome-infected mice in three independent experiments. This result exceeded expectations because the drug was optimized against a human EGFR type 2 (HER2) (54); it was neither optimized against a trypanosomal protein nor tested in a phenotypic screen against T. brucei. Although T. brucei lacks HER2, lapatinib binds four trypanosome protein kinases (22), three of which are essential for the viability of the parasite (55–57). Therefore, it is conceivable that the drug modulates the activity of one or more of those enzymes in killing and controlling the trypanosome infection.

CI-1033 is a 4-anilinoquinazoline derivative (30), like lapatinib. In the in vitro cell replication assay, CI-1033 had a GI50 in the same range as that of lapatinib (Table 1). However, CI-1033 dramatically underperformed lapatinib in the mouse model of HAT (Fig. 4). The reason for this large difference in the performances of the two drugs might lie in the different pharmacokinetics and distribution of the drugs in mice, which is most likely influenced by the chemical substituents on the common 4-anilinoquinazoline scaffold of the drugs (20, 30) (Fig. 1A). The borderline efficacy of CI-1033 might also be ascribed to our use of a smaller amount of the drug and less-frequent doses: 30 mg/kg once daily compared to 100 mg/kg twice daily for lapatinib. We had to use a smaller amount of CI-1033 because higher amounts are toxic to mice, an observation supported by our in vitro studies with HeLa cells (Fig. 1G and H). Either way, these observations highlight the notion that new synthetic 4-anilinoquinazoline derivatives might be produced against T. brucei, using lessons learned from comparing the structures of lapatinib and CI-1033. In support of this principle, the Pollastri group has synthesized nine new lapatinib derivatives that are 5 to 30 times more potent than lapatinib in whole-cell screening assays (28). Thus, 4-anilinoquinazoline is a good scaffold for antitrypanosomal lead optimization.

AEE788 (25) was equipotent with lapatinib in reducing parasitemia but failed to cure trypanosome-infected mice (Fig. 5). The strong reduction of parasitemia levels during the oral administration of AEE788 treatment suggests that a pyrrolopyrimidine scaffold (also present in PKI-166 [Table 1]) can be the basis of a medicinal chemistry effort to synthesize new antitrypanosomal derivatives (for examples, see references 58–60) that might be orally bioavailable.

To summarize, the oral administration of lapatinib and AEE788 to trypanosome-infected mice led to a reduction in parasitemia levels, an increase in the mean survival of mice, and in the case of lapatinib, a cure of trypanosome-infected mice. These studies provide proof of the principle that orally bioavailable drugs against PTKs have a place in a portfolio of new chemical entities against the African trypanosome (38). Specifically, the 4-anilinoquinazoline and pyrrolopyrimidine chemical entities might be the focus of a medicinal chemistry scaffold repurposing effort. The goals advanced here are achievable, as demonstrated recently with derivatives of lapatinib and danusertib (28, 48). Finally, we recognize that a significant number of HAT patients present with late-stage disease, when the trypanosome has crossed the blood-brain barrier (reviewed in reference 9). Thus, prized new drugs must have the ability to enter the central nervous system. Fortunately, lapatinib and AEE788 are detected in brain tissue (61–64), so we are hopeful that new derivatives synthesized to treat HAT will retain the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mike Pollastri (Northeastern University) for discussions and for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant R21AI076647.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 January 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Croft SL, Barrett MP, Urbina JA. 2005. Chemotherapy of trypanosomiases and leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 21:508–512. 10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renslo AR, McKerrow JH. 2006. Drug discovery and development for neglected parasitic diseases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2:701–710. 10.1038/nchembio837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKerrow JH. 1996. Parasitic infections–molecular diagnosis and rational drug design. Biologicals 24:207–208. 10.1006/biol.1996.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett MP, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. 1999. Recent advances in identifying and validating drug targets in trypanosomes and leishmanias. Trends Microbiol. 7:82–88. 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01433-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammarton TC, Mottram JC, Doerig C. 2003. The cell cycle of parasitic protozoa: potential for chemotherapeutic exploitation. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 5:91–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. 2002. The druggable genome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:727–730. 10.1038/nrd892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy LW, Peet NP. 2004. The multiple orthogonal tools approach to define molecular causation in the validation of druggable targets. Drug Discov. Today 9:117–126. 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02969-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pink R, Hudson A, Mouriès MA, Bendig M. 2005. Opportunities and challenges in antiparasitic drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4:727–740. 10.1038/nrd1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs RT, Nare B, Phillips MA. 2011. State of the art in African trypanosome drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 11:1255–1274. 10.2174/156802611795429167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelb MH, Van Voorhis WC, Buckner FS, Yokoyama K, Eastman R, Carpenter EP, Panethymitaki C, Brown KA, Smith DF. 2003. Protein farnesyl and N-myristoyl transferases: piggy-back medicinal chemistry targets for the development of antitrypanosomatid and antimalarial therapeutics. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 126:155–163. 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00282-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelb MH, Hol WG. 2002. Parasitology. Drugs to combat tropical protozoan parasites. Science 297:343–344. 10.1126/science.1073126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollastri MP, Campbell RK. 2011. Target repurposing for neglected diseases. Future Med. Chem. 3:1307–1315. 10.4155/fmc.11.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson LN. 2009. Protein kinase inhibitors: contributions from structure to clinical compounds. Q. Rev. Biophys. 42:1–40. 10.1017/S0033583508004745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sebolt-Leopold JS, English JM. 2006. Mechanisms of drug inhibition of signalling molecules. Nature 441:457–462. 10.1038/nature04874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levitzki A, Mishani E. 2006. Tyrphostins and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:93–109. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhagwat M, Aravind L. 2007. PSI-BLAST tutorial. Methods Mol. Biol. 395:177–186. 10.1007/978-1-59745-514-5_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osherov N, Levitzki A. 1994. Epidermal-growth-factor-dependent activation of the src-family kinases. Eur. J. Biochem. 225:1047–1053. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.1047b.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu XF, Liu ZC, Xie BF, Li ZM, Feng GK, Yang D, Zeng YX. 2001. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 inhibits cell proliferation and arrests cell cycle in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 169:27–32. 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00547-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grünwald V, Hidalgo M. 2003. Development of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor OSI-774. Semin. Oncol. 30(3 Suppl 6):23–31. 10.1016/S0093-7754(03)70022-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lackey KE. 2006. Lessons from the drug discovery of lapatinib, a dual ErbB1/2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 6:435–460. 10.2174/156802606776743156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia W, Mullin RJ, Keith BR, Liu LH, Ma H, Rusnak DW, Owens G, Alligood KJ, Spector NL. 2002. Anti-tumor activity of GW572016: a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks EGF activation of EGFR/erbB2 and downstream Erk1/2 and AKT pathways. Oncogene 21:6255–6263. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katiyar S, Kufareva I, Behera R, Thomas SM, Ogata Y, Pollastri M, Abagyan R, Mensa-Wilmot K. 2013. Lapatinib-binding protein kinases in the African trypanosome: identification of cellular targets for kinase-directed chemical scaffolds. PLoS One 8:e56150. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanya S, Mensa-Wilmot K. 2010. Diacylglycerol-stimulated endocytosis of transferrin in trypanosomatids is dependent on tyrosine kinase activity. PLoS One 5:e8538. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanya S, Hardin CF, Steverding D, Mensa-Wilmot K. 2009. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C regulates transferrin endocytosis in the African trypanosome. Biochem. J. 417:685–694. 10.1042/BJ20080167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traxler P, Allegrini PR, Brandt R, Brueggen J, Cozens R, Fabbro D, Grosios K, Lane HA, McSheehy P, Mestan J, Meyer T, Tang C, Wartmann M, Wood J, Caravatti G. 2004. AEE788: a dual family epidermal growth factor receptor/ErbB2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 64:4931–4941. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slichenmyer WJ, Elliott WL, Fry DW. 2001. CI-1033, a pan-erbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Semin. Oncol. 28(5 Suppl 16):80–85. 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90285-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen LF, Lenehan PF, Eiseman IA, Elliott WL, Fry DW. 2002. Potential benefits of the irreversible pan-erbB inhibitor, CI-1033, in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin. Oncol. 29(3 Suppl 11):11–21. 10.1016/S0093-7754(02)70122-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel G, Karver CE, Behera R, Guyett PJ, Sullenberger C, Edwards P, Roncal NE, Mensa-Wilmot K, Pollastri MP. 2013. Kinase scaffold repurposing for neglected disease drug discovery: discovery of an efficacious, lapatinib-derived lead compound for trypanosomiasis. J. Med. Chem. 56:3820–3832. 10.1021/jm400349k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirumi H, Hirumi K. 1994. Axenic culture of African trypanosome bloodstream forms. Parasitol. Today 10:80–84. 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90402-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smaill JB, Showalter HD, Zhou H, Bridges AJ, McNamara DJ, Fry DW, Nelson JM, Sherwood V, Vincent PW, Roberts BJ, Elliott WL, Denny WA. 2001. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. 18. 6-Substituted 4-anilinoquinazolines and 4-anilinopyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidines as soluble, irreversible inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Med. Chem. 44:429–440. 10.1021/jm000372i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, Sawyers CL. 2002. Growth inhibitory effects of the dual ErbB1/ErbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI-166 on human prostate cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 62:5254–5259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruns CJ, Solorzano CC, Harbison MT, Ozawa S, Tsan R, Fan D, Abbruzzese J, Traxler P, Buchdunger E, Radinsky R, Fidler IJ. 2000. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling by a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor leads to apoptosis of endothelial cells and therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 60:2926–2935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Pryer NK, Cherrington JM. 2003. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2:471–478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, Louie SG, Christensen JG, Li G, Schreck RE, Abrams TJ, Ngai TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Carver J, Chan E, Moss KG, Haznedar JO, Sukbuntherng J, Blake RA, Sun L, Tang C, Miller T, Shirazian S, McMahon G, Cherrington JM. 2003. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin. Cancer Res. 9:327–337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rugo HS, Herbst RS, Liu G, Park JW, Kies MS, Steinfeldt HM, Pithavala YK, Reich SD, Freddo JL, Wilding G. 2005. Phase I trial of the oral antiangiogenesis agent AG-013736 in patients with advanced solid tumors: pharmacokinetic and clinical results. J. Clin. Oncol. 23:5474–5483. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. 2000. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of Abelson tyrosine kinase. Science 289:1938–1942. 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang G, Kim CN, Perkins CL, Ramadevi N, Winton E, Wittmann S, Bhalla KN. 2000. CGP57148B (STI-571) induces differentiation and apoptosis and sensitizes Bcr-Abl-positive human leukemia cells to apoptosis due to antileukemic drugs. Blood 96:2246–2253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nwaka S, Ramirez B, Brun R, Maes L, Douglas F, Ridley R. 2009. Advancing drug innovation for neglected diseases—criteria for lead progression. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e440. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai F, Freeman BB, III, Fraga CH, Fouladi M, Stewart CF. 2006. Determination of lapatinib (GW572016) in human plasma by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS). J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 831:169–175. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Midgley RS, Kerr DJ, Flaherty KT, Stevenson JP, Pratap SE, Koch KM, Smith DA, Versola M, Fleming RA, Ward C, O'Dwyer PJ, Middleton MR. 2007. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of lapatinib in combination with infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan. Ann. Oncol. 18:2025–2029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvo E, Tolcher AW, Hammond LA, Patnaik A, de Bono JS, Eiseman IA, Olson SC, Lenehan PF, McCreery H, Lorusso P, Rowinsky EK. 2004. Administration of CI-1033, an irreversible pan-erbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is feasible on a 7-day on, 7-day off schedule: a phase I pharmacokinetic and food effect study. Clin. Cancer Res. 10:7112–7120. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellis AG, Doherty MM, Walker F, Weinstock J, Nerrie M, Vitali A, Murphy R, Johns TG, Scott AM, Levitzki A, McLachlan G, Webster LK, Burgess AW, Nice EC. 2006. Preclinical analysis of the analinoquinazoline AG1478, a specific small molecule inhibitor of EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:1422–1434. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakagawa K, Minami H, Kanezaki M, Mukaiyama A, Minamide Y, Uejima H, Kurata T, Nogami T, Kawada K, Mukai H, Sasaki Y, Fukuoka M. 2009. Phase I dose-escalation and pharmacokinetic trial of lapatinib (GW572016), a selective oral dual inhibitor of ErbB-1 and -2 tyrosine kinases, in Japanese patients with solid tumors. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 39:116–123. 10.1093/jjco/hyn135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudachek SF, Gustafson DL. 2013. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of lapatinib developed in mice and scaled to humans. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 40:157–176. 10.1007/s10928-012-9295-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon GR, Garrett CR, Olson SC, Langevin M, Eiseman IA, Mahany JJ, Williams CC, Lush R, Daud A, Munster P, Chiappori A, Fishman M, Bepler G, Lenehan PF, Sullivan DM. 2006. Increased bioavailability of intravenous versus oral CI-1033, a pan erbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor: results of a phase I pharmacokinetic study. Clin. Cancer Res. 12:4645–4651. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jakobsen PH, Wang MW, Nwaka S. 2011. Innovative partnerships for drug discovery against neglected diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1221. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. 2003. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J. Health Econ. 22:151–185. 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ochiana SO, Pandarinath V, Wang Z, Kapoor R, Ondrechen MJ, Ruben L, Pollastri MP. 2013. The human Aurora kinase inhibitor danusertib is a lead compound for anti-trypanosomal drug discovery via target repurposing. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 62:777–784. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Field MC. 2009. Drug screening by crossing membranes: a novel approach to identification of trypanocides. Biochem. J. 419:e1–e3. 10.1042/BJ20090283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patham B, Duffy J, Lane A, Davis RC, Wipf P, Fewell SW, Brodsky JL, Mensa-Wilmot K. 2009. Post-translational import of protein into the endoplasmic reticulum of a trypanosome: an in vitro system for discovery of anti-trypanosomal chemical entities. Biochem. J. 419:507–517. 10.1042/BJ20081787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steverding D. 2000. The transferrin receptor of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitol. Int. 48:191–198. 10.1016/S1383-5769(99)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brose N, Betz A, Wegmeyer H. 2004. Divergent and convergent signaling by the diacylglycerol second messenger pathway in mammals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14:328–340. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baselga J. 2006. Targeting tyrosine kinases in cancer: the second wave. Science 312:1175–1178. 10.1126/science.1125951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood ER, Truesdale AT, McDonald OB, Yuan D, Hassell A, Dickerson SH, Ellis B, Pennisi C, Horne E, Lackey K, Alligood KJ, Rusnak DW, Gilmer TM, Shewchuk L. 2004. A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 64:6652–6659. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urbaniak MD. 2009. Casein kinase 1 isoform 2 is essential for bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 166:183–185. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Z, Umeyama T, Wang CC. 2008. The chromosomal passenger complex and a mitotic kinesin interact with the Tousled-like kinase in trypanosomes to regulate mitosis and cytokinesis. PLoS One 3:e3814. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ojo KK, Gillespie JR, Riechers AJ, Napuli AJ, Verlinde CL, Buckner FS, Gelb MH, Domostoj MM, Wells SJ, Scheer A, Wells TN, Van Voorhis WC. 2008. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 is a potential drug target for African trypanosomiasis therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3710–3717. 10.1128/AAC.00364-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lippa B, Pan G, Corbett M, Li C, Kauffman GS, Pandit J, Robinson S, Wei L, Kozina E, Marr ES, Borzillo G, Knauth E, Barbacci-Tobin EG, Vincent P, Troutman M, Baker D, Rajamohan F, Kakar S, Clark T, Morris J. 2008. Synthesis and structure based optimization of novel Akt inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18:3359–3363. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark MP, George KM, Bookland RG, Chen J, Laughlin SK, Thakur KD, Lee W, Davis JR, Cabrera EJ, Brugel TA, VanRens JC, Laufersweiler MJ, Maier JA, Sabat MP, Golebiowski A, Easwaran V, Webster ME, De B, Zhang G. 2007. Development of new pyrrolopyrimidine-based inhibitors of Janus kinase 3 (JAK3). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17:1250–1253. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blake JF, Kallan NC, Xiao D, Xu R, Bencsik JR, Skelton NJ, Spencer KL, Mitchell IS, Woessner RD, Gloor SL, Risom T, Gross SD, Martinson M, Morales TH, Vigers GP, Brandhuber BJ. 2010. Discovery of pyrrolopyrimidine inhibitors of Akt. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20:5607–5612. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polli JW, Humphreys JE, Harmon KA, Castellino S, O'Mara MJ, Olson KL, John-Williams LS, Koch KM, Serabjit-Singh CJ. 2008. The role of efflux and uptake transporters in [N-{3-chloro-4-[(3-fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-6-[5-({[2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]amino}methyl)-2-furyl]-4-quinazolinamine (GW572016, lapatinib) disposition and drug interactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36:695–701. 10.1124/dmd.107.018374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gluck S, Castrellon A. 2009. Lapatinib plus capecitabine resolved human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive brain metastases. Am. J. Ther. 16:585–590. 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31818bee2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meco D, Servidei T, Zannoni GF, Martinelli E, Prisco MG, de Waure C, Riccardi R. 2010. Dual inhibitor AEE788 reduces tumor growth in preclinical models of medulloblastoma. Transl. Oncol. 3:326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berezowska S, Diermeier-Daucher S, Brockhoff G, Busch R, Duyster J, Grosu AL, Schlegel J. 2010. Effect of additional inhibition of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 with the bispecific tyrosine kinase inhibitor AEE788 on the resistance to specific EGFR inhibition in glioma cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 26:713–721. 10.3892/ijmm_00000518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]