Abstract

Data regarding the effect of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism on plasma efavirenz concentrations and 96-week virologic responses in patients coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis (TB) are still unavailable. A total of 139 antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults with active TB were prospectively enrolled to receive efavirenz 600 mg-tenofovir 300 mg-lamivudine 300 mg. Eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within CYP2B6 were genotyped. Seven SNPs, including 64C→T, 499C→G, 516G→T, 785A→G, 1375A→G, 1459C→T, and 21563C→T, were included for CYP2B6 haplotype determination. The CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism was studied in 48 patients who carried haplotype *1/*1. At 12 and 24 weeks after antiretroviral therapy, plasma efavirenz concentrations at 12 h after dosing were measured. Plasma HIV RNA was monitored every 12 weeks for 96 weeks. Of 48 patients {body weight [mean ± standard deviation (SD)], 56 ± 10 kg}, 77% received a rifampin-containing anti-TB regimen. No drug resistance-associated mutation was detected at baseline. The frequencies of the wild type (18492TT) and the heterozygous (18492TC) and homozygous (18492CC) mutants of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism were 39%, 42%, and 19%, respectively. At 12 weeks, mean (±SD) efavirenz concentrations of patients who carried the 18492TT, 18492TC, and 18492CC mutants were 2.8 ± 1.6, 1.7 ± 0.9, and 1.4 ± 0.5 mg/liter, respectively (P = 0.005). At 24 weeks, the efavirenz concentrations of the corresponding groups were 2.4 ± 0.8, 1.7 ± 0.8, and 1.2 ± 0.4 mg/liter, respectively (P = 0.003). A low efavirenz concentration was independently associated with 18492T→C (β = −0.937, P = 0.004) and high body weight (β = −0.032, P = 0.046). At 96 weeks, 19%, 17%, and 28% of patients carrying the 18492TT, 18492TC, and 18492CC mutants, respectively, had plasma HIV RNA levels of >40 copies/ml and developed efavirenz-associated mutations (P = 0.254). In summary, the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism compromises efavirenz concentrations in patients who carry CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1 and are coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

Efavirenz has been recommended as the preferred option of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) when combined with two other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors for first-line antiretroviral regimens (1). This drug is primarily metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) enzyme into 8-hydroxy-efavirenz, and the remaining amount is metabolized via accessory pathways involving CYP2A6, CYP3A4/5, and UGT2B7 (2–4). In contrast, rifamycin is a crucial component in the treatment of tuberculosis (TB). Rifampin is a strong hepatic cytochrome P450 inducer, resulting in a marked reduction of exposure for several antiretroviral drugs, including efavirenz, but in a lesser magnitude (5). Previous studies demonstrated favorable outcomes in patients coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis and treated with efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) who had concurrently received rifampin (6–9). Many current HIV treatment guidelines recommend efavirenz-based ART for patients who are receiving rifampin (1, 10, 11).

Nonetheless, concerns persist regarding the variation in plasma efavirenz concentrations in such patients. Polymorphisms in CYP2B6, resulting from a nucleotide substitution at some positions, are associated with a lower rate of efavirenz metabolism and lead to high efavirenz exposure. Many studies have reported a relationship between the CYP2B6 516G→T variant and an increased efavirenz concentration in plasma and intracellular compartments, as well as a higher risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events (12). Conversely, variable activity of cytochrome P450 may result in increased drug clearance and may lead to a suboptimal efavirenz concentration (12). Furthermore, HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients may be greatly impacted by this particular effect while taking rifampin. Resistant HIV quasispecies can rapidly emerge during periods of suboptimal antiretroviral drug concentrations (13–15). However, data regarding pharmacogenetic markers correlated with suboptimal antiretroviral drug concentrations, and data on long-term clinical treatment outcomes are limited. Therefore, this study was aimed to investigate the CYP2B6 18492T-to-C (CYP2B6 18492T→C) substitutions that are associated with plasma efavirenz concentrations, as well as 96-week virologic responses in patients coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a prospective open-label trial to evaluate the frequency of CYP2B6 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and haplotypes in 139 adult Thai patients coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis at the Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand (16). The institutional ethics committees of the Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute and the Thai Ministry of Public Health approved the study. All participating patients provided written informed consent. The period of enrollment was October 2009 to May 2011. The patients were followed for 96 weeks after the initiation of ART to examine (i) the pharmacogenetic markers of CYP2B6 and biological factors which were associated with low plasma efavirenz concentrations at week 12 while they were receiving a rifampin-containing anti-TB regimen and at week ≥24 when the anti-TB regimen had already been discontinued for at least 4 weeks and (ii) immunologic and virologic responses at 96 weeks after ART initiation. Patient adherence to the regimens was measured by self-reports and questionnaires.

Inclusion criteria were (i) HIV-infected patients 18 to 60 years of age, (ii) newly clinically diagnosed active tuberculosis, positive acid-fast staining, or a positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, (iii) treatment with an antituberculous regimen 4 to 12 weeks prior to enrollment, and (iv) no previous ART. All patients were started on a once-daily antiretroviral regimen of efavirenz 600 mg combined with tenofovir 300 mg and lamivudine 300 mg at bedtime. ART was initiated between 4 and 12 weeks after the initiation of tuberculosis treatment. The dosage of rifampin was 450 mg/day for patients with a body weight of ≤50 kg or 600 mg/day for those with a body weight of >50 kg. The standard antituberculosis regimen was isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for the first 2 months. Based on the clinical and microbiological responses of the patients, isoniazid and rifampin were continued for 4 to 7 months. For patients who initially could not tolerate rifampin due to adverse effects or hypersensitivity and who received other antituberculosis regimens that excluded rifampin, the period of treatment was extended to 9 to 12 months. The patients had follow-up visits at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks and every 12 weeks thereafter, at which times they were assessed clinically and/or had blood samples taken. Genotypic resistance testing (TRUGENE HIV-1 genotyping assay; Visible Genetics Inc., Toronto, Canada) was performed at week 0 and after the patient was documented to have virologic failure.

At week 0, DNA was isolated from the EDTA cell pellets using the QIAamp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genomic DNA was quantified by a NanoDrop UV spectrophotometer ND-1000 at 260 nm (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). A total of eight SNPs within CYP2B6 were genotyped. Seven of them, including 64C→T, 499C→G, 516G→T, 785A→G, 1375A→G, 1459C→T, and 21563C→T, were included for CYP2B6 haplotype determination. Haplotype determination was interpreted using the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database (http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2b6.htm). CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1 was defined as no heterozygous or homozygous mutation in seven SNPs. SNPs 516G→T and 785A→G were reported to influence plasma efavirenz concentrations (17), and the CYP2B6 SNP 21563C→T polymorphism was identified using the International Haplotype Mapping Project (HapMap) (http://www.hapmap.org), which included Japanese and Han Chinese subjects. SNP 499C→G was associated with high plasma efavirenz concentrations in Japanese subjects, and the remaining three SNPs, i.e., 64C→T, 1375A→G, and 1459C→T, were reported in Chinese subjects (18). The CYP2B6 18492T→C SNP was identified using HapMap (www.hapmap.org) data on Japanese and Han Chinese populations with an r2 value of >0.8 (19). SNPs were genotyped at the Laboratory for Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University. To determine efavirenz concentrations, fasting plasma samples were collected 12 h after receiving ART and were tested using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography assay at 12 weeks after ART initiation while receiving antituberculosis treatment and at ≥24 weeks following the discontinuation of antituberculosis treatment. All patients were instructed to strictly adhere to their medications for at least 2 weeks prior to measurement of their plasma efavirenz concentrations. This assay was developed at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. CD4 cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were assessed by real-time PCR at baseline and every 12 weeks thereafter for a total of 96 weeks. Virologic failure was defined as the inability to achieve or maintain suppression of viral replication at <40 copies/ml after 24 weeks of ART or having a detectable HIV RNA level of >200 copies/ml after virologic suppression.

Frequencies (%) and medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs] at the 25th and 75th percentiles) were used to describe the clinical and laboratory parameters (Table 1). All possible risk factors associated with a low plasma efavirenz concentration and virologic failure at 96 weeks were evaluated with a linear regression model and a binary logistic regression model by adjusting for confounding factors, respectively. Any factors with a P value of <0.05 were included in the multivariate regression model. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The β value and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated. The interpatient variability of plasma efavirenz concentrations was expressed as a coefficient of variation (CV). Genotype distributions were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using exact tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and pharmacogenetic parameters of patientsa coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis

| Parameter | Valueb |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Male | 37 (77) |

| Age (yr) | 38 ± 8 |

| Body wt (kg) | 56 ± 10 |

| Patients on rifampin-containing antituberculosis regimen | 37 (77) |

| Laboratory data | |

| CD4 cells (cells/mm3) | 41 (14–132) |

| % of CD4 cells | 6 (2–12) |

| Log plasma HIV RNA (log copies/ml) | 5.7 (5.3–6.1) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 10.6 (9.2–12.2) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (mg/dl) | 110 (71–191) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/liter) | 35 (26–46) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/liter) | 24 (18–41) |

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) |

| Hepatitis B virus antigen positive | 3 (6) |

| Hepatitis C antibody positive | 4 (8) |

| Pharmacogenetic data | |

| 18492T→C SNP | |

| TT | 19 (39) |

| TC | 20 (42) |

| CC | 9 (19) |

n = 48.

The data shown are no. (%), mean ± SD, or median (IQR).

RESULTS

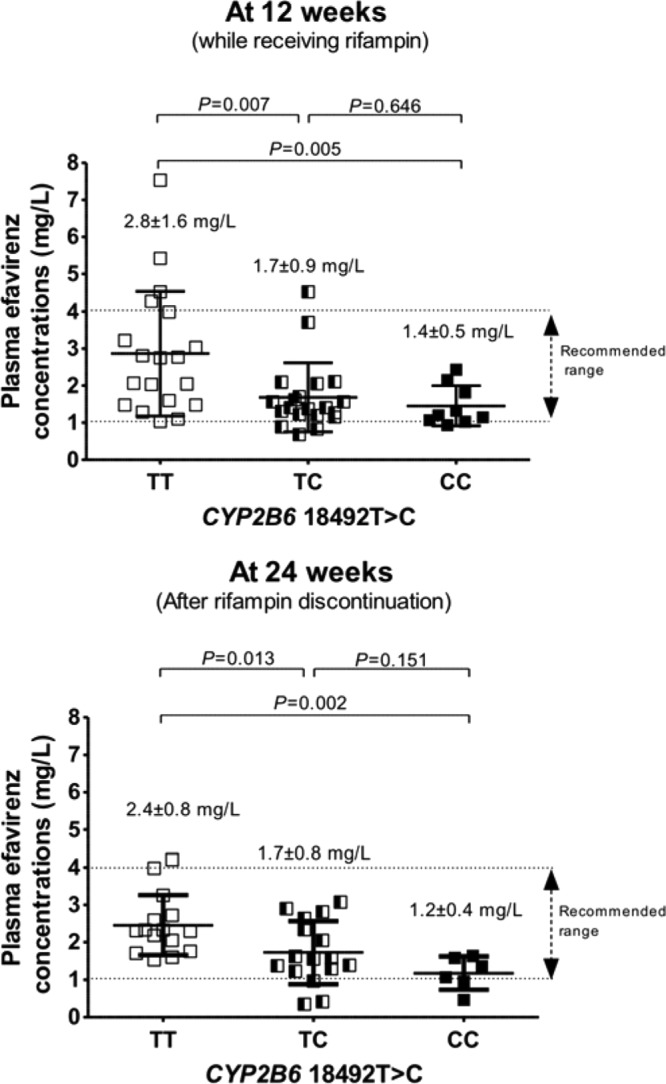

Of 139 patients coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis, CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1 was identified in 48 patients. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and pharmacogenetic parameters of the 48 patients. The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) body weight of the patients was 56 ± 10 kg, and 77% had received a rifampin-containing anti-TB regimen. None of the patients had resistance-associated mutations to the study antiretroviral drugs prior to ART initiation. The frequencies of the wild type and the heterozygous and homozygous mutants of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism were 39%, 42%, and 19%, respectively. Figure 1 displays scatter plots of plasma efavirenz concentrations by the 18492T→C SNP. At 12 weeks, interpatient variations in plasma efavirenz concentrations of the corresponding patients who carried the 18492TT, 18492TC, and 18492CC mutants were 57%, 53%, and 36%, respectively. Mean (±SD) plasma efavirenz concentrations of the corresponding patients were 2.8 ± 1.6, 1.7 ± 0.9, and 1.4 ± 0.5 mg/liter, respectively (P = 0.005). The proportions of patients who had efavirenz concentrations of <1 mg/liter were 0%, 15%, and 11%, respectively. At 24 weeks, the interpatient variations in plasma efavirenz concentrations of patients who carried the 18492TT, 18492TC, and 18492CC mutants were 33%, 47%, and 33%, respectively. The plasma efavirenz concentrations of patients who carried the 18492TT, 18492TC, and 18492CC mutants were 2.4 ± 0.8, 1.7 ± 0.8, and 1.2 ± 0.4 mg/liter, respectively (P = 0.003). The proportions of patients who had efavirenz concentrations of <1 mg/liter were 0%, 15%, and 22%, respectively. The mean (±SD) body weights at 12 and 24 weeks were 58 ± 10 and 59 ± 10 kg (P <0.001, compared with those at week 0), respectively.

FIG 1.

Scatter plots of plasma efavirenz concentrations at 12 weeks (while concurrently receiving rifampin) and at 24 weeks (after rifampin discontinuation) by the CYP2B6 18492T→C SNP. Each dot represents one patient. The middle bars indicate the means, and the upper and lower bars represent the standard deviations of the means.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of possible factors associated with low plasma efavirenz concentrations at 12 and 24 weeks are shown in Table 2. Overall, low plasma efavirenz concentrations at both 12 and 24 weeks were associated with the 18492T→C SNP and a high body weight (P < 0.05). At 96 weeks, 8 (17%) of the patients had plasma HIV RNA levels of >40 copies/ml, 4 (8%) were lost to follow-up, and 3 (6%) died. Table 3 lists virologic and immunologic responses at 96 weeks by the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism. All patients with virologic failures developed nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance-associated mutations.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of plasma efavirenz concentrations at weeks 12 and 24 as the dependent variable

| Time point and parametera | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | β | 95% CIb | P | β | 95% CI | |

| 12 wk | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male gender | 0.407 | 0.395 | −0.555 to 1.344 | |||

| Age | 0.463 | −0.018 | −0.067 to 0.031 | |||

| Body wt | 0.025 | −0.039 | −0.074 to −0.005 | 0.004 | −0.948 | −1.573 to −0.323 |

| On rifampin-containing regimen | 0.321 | −0.471 | −1.418 to 0.475 | |||

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| CD4 cells at wk 0 | 0.215 | 0.003 | −0.002 to 0.008 | |||

| Log plasma HIV RNA at wk 0 | 0.734 | 0.116 | −0.590 to 0.821 | |||

| Serum ALP | 0.622 | −0.001 | −0.003 to 0.002 | |||

| AST | 0.497 | 0.006 | −0.011 to –0.022 | |||

| ALT | 0.452 | −0.007 | −0.026 to 0.012 | |||

| Hepatitis B virus antigen positive | 0.042 | 1.651 | 0.064 to 3.238 | 0.508 | −0.478 | −1.924 to 0.967 |

| Hepatitis C antibody positive | 0.919 | 0.074 | −1.380 to 1.529 | |||

| Pharmacogenetic data | ||||||

| T18492C SNP | 0.001 | −1.253 | −1.986 to −0.519 | 0.004 | −0.948 | −1.573 to −0.323 |

| 24 wk | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male gender | 0.273 | −0.368 | −1.039 to 0.303 | |||

| Age | 0.693 | −0.008 | −0.046 to 0.031 | |||

| Body wt | 0.498 | −0.010 | −0.041 to 0.020 | |||

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| CD4 cells at week 0 | 0.754 | −0.001 | −0.005 to 0.003 | |||

| Log plasma HIV RNA at week 0 | 0.497 | −0.174 | −0.687 to 0.340 | |||

| Serum ALP | 0.692 | −0.001 | −0.007 to 0.005 | |||

| AST | 0.772 | −0.001 | −0.010 to 0.007 | |||

| Hepatitis B virus antigen positive | 0.667 | 0.386 | −1.480 to 2.252 | |||

| Hepatitis C antibody positive | 0.024 | 1.057 | 0.150 to 1.964 | 0.078 | −0.762 | −0.089 to 1.614 |

| Pharmacogenetic data | ||||||

| T18492C SNP | 0.002 | −0.881 | −1.420 to −0.343 | 0.007 | −0.764 | −1.302 to −0.225 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 3.

Virologic and immunologic responses at 96 weeks by patients with the CYP2BC 18492T→C polymorphism

| Parameter | Mutant (n) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18492TT (19) | 18492TC (20) | 18492CC (9) | ||

| No. of patients with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels at >40 copies/ml/total no. of patients (%) | 3/16 (19) | 3/18 (17) | 2/7 (28) | 0.254 |

| CD4 cell count (median [IQR]) (cells/mm3) | 288 (133–425) | 269 (163–378) | 239 (34–368) | 0.886 |

DISCUSSION

Many genetic polymorphisms associated with high efavirenz concentrations have been identified in CYP2B6 among patients with HIV monoinfection (12). This is the first study revealing that patients who were coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis and who had CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1 and carried a heterozygous or homozygous mutant of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism had markedly lower plasma efavirenz concentrations. To date, the recommended range of plasma efavirenz concentrations at 12 h after dosing is proposed to be 1 to 4 mg/liter (1, 15). Steady-state plasma efavirenz concentrations were reduced by approximately 30% to 50% in the patients who had this allelic variant. Note that the means of efavirenz concentrations in the patients who carried heterozygous and homozygous mutants were 1.7 mg/liter and 1.2 mg/liter, respectively. Compared to a previous study in patients with HIV monoinfection, efavirenz concentrations of the corresponding patients were 2.0 mg/liter and 1.7 mg/liter, respectively (19). Patients in the current study were therefore more vulnerable to suboptimal efavirenz concentrations. This finding can be explained by the effect of the concurrent use of rifampin. Another consideration is that a number of patients maintained their achieved concentrations above the recommended minimum level of 1 mg/liter, but these concentrations were very marginal. These findings are consistent at both time points of efavirenz measurements. The consideration of a minimum concentration of 1 mg/liter was based upon an acceptable 70% treatment response rate (15), whereas Stahle and colleagues suggested raising that minimum to achieve at least an 80% response rate (20). Previous studies have shown that patients who had low or subtherapeutic efavirenz concentrations had an increased chance for the development of HIV-resistant strains and subsequent treatment failure (15, 21, 22). Moreover, efavirenz has a low genetic barrier to resistance; in fact, a single mutation results in high-level resistance to not only efavirenz but also to other drugs in the same class (23). Of note, almost one-third of the patients with a homozygous mutant of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism experienced virologic failure, and all of them developed NNRTI-associated mutations. This number is considered to be high, especially for patients with the wild type and the heterozygous mutant of CYP2B6 18492T→C, which was <20%, although statistical significance was not reached due to the small sample size. Therefore, maintaining an adequate drug concentration is very important for achieving long-term virologic suppression and preventing collateral damage to other drugs. The frequencies of heterozygous and homozygous mutations of CYP2B6 18492T→C accounted for 61% in our cohort, which is considered to be relatively high. As mentioned, rifampin is an essential drug for the treatment of tuberculosis and is a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver, resulting in reduced plasma concentrations of efavirenz (5). All things considered, such patients are highly vulnerable to subsequent failure of HIV treatment, although no correlation was found between CYP2B6 18492T→C and virologic failure after 96 weeks of treatment, probably because of the relatively small sample size. Therefore, a larger-scale study remains necessary to confirm the findings.

In the current study, less interpatient variability of efavirenz concentrations was observed during concurrent use of efavirenz and rifampin, and this trend was consistent after rifampin discontinuation. Substantial interpatient variability of efavirenz concentrations with a >100% coefficient of variation after fixed standard doses is well known. Previous reports in Thais demonstrated wide ranges of interpatient variability, ranging from 77% to 136% (6, 24). This can be explained by the fact that other SNPs were excluded before the final analysis, and only the patients who carried CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1 were enrolled, suggesting that other factors that potentially influence efavirenz concentration were minimized, even if variation is usually even greater when efavirenz was coadministered with rifampin (25, 26).

In addition, a high patient body weight was found to be an important predictive factor of a low drug concentration. Plasma efavirenz concentrations persistently decreased at 0.9 mg/liter for every 10 kg of increased body weight. The optimal efavirenz dosage when coadministered with rifampin is still debated. According to the current U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines (1), experts recommend starting with an efavirenz dose of 600 mg/day and monitoring the patient for virological response; for patients weighing >60 kg, the DHHS recommends increasing the dose to 800 mg/day. The British HIV Association (BHIVA) treatment guidelines recommend using a 50-kg body weight as the cutoff for increasing the efavirenz dosage (11). In contrast, World Health Organization guidelines for resource-limited settings recommend using efavirenz at 600 mg/day only (10). As a consequence, pharmacogenetic markers may play a more important role in determining the appropriate dosage of efavirenz in the future, particularly with concurrent rifampin administration. With regard to virologic and immunologic responses, there appears to be no correlation between 96-week treatment responses and the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism, possibly because of the relatively small sample size. Nevertheless, virologic failure developed relatively early after ART initiation and might have been related to the marginal therapeutic concentration of efavirenz in these patients. Further study is needed.

A number of limitations to this study should be considered. First, the frequency of the CYP2B6 18492T→C polymorphism in other ethnicities is somewhat different based upon the HapMap (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Genetic differences in the metabolism of efavirenz influence drug exposure. Thus, our results may not be completely applicable to other ethnic groups with different frequencies of polymorphisms. Second, we studied a small sample, which resulted in some factors in previous studies that could not be identified, such as concurrently receiving rifampin with efavirenz (8). Third, pharmacogenetic study was not performed for other accessory pathways, including CYP2A6, CYP3A4/5, and UGT2B7 (27). However, the current study demonstrated that the pharmacogenetic marker (CYP2B6 18492T→C) and biological factors (weight) can influence HIV treatment. Ultimately, the duration of studying pharmacogenetic markers, plasma drug concentrations, and final treatment outcomes was different in the current study because we aimed to consider pharmacogenetic markers and drug concentrations in patients while receiving and after discontinuing rifampin in the early period of ART to predict long-term treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, the CYP2B6 T-to-C substitution at gene position 18492 compromises efavirenz-based antiretroviral regimens, particularly in patients with high body weight who are coinfected with HIV and tuberculosis and who carry CYP2B6 haplotype *1/*1. Further study with regard to integrating this pharmacogenetic marker in clinical practice should be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the patients who participated in this study.

This study was funded by grants from The Thailand Research Fund (RSA5380001), the Ministry of Public Health (Thailand), the Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute (Thailand), and The Mahidol University/The Thailand Research Fund and the Office of the Higher Education Commission (new researcher grant MRG5480136).

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 February 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. 2013. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf Accessed 1 April 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desta Z, Saussele T, Ward B, Blievernicht J, Li L, Klein K, Flockhart DA, Zanger UM. 2007. Impact of CYP2B6 polymorphism on hepatic efavirenz metabolism in vitro. Pharmacogenomics 8:547–558. 10.2217/14622416.8.6.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutlib AE, Chen H, Nemeth GA, Markwalder JA, Seitz SP, Gan LS, Christ DD. 1999. Identification and characterization of efavirenz metabolites by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and high field NMR: species differences in the metabolism of efavirenz. Drug Metab. Dispos. 27:1319–1333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward BA, Gorski JC, Jones DR, Hall SD, Flockhart DA, Desta Z. 2003. The cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is the main catalyst of efavirenz primary and secondary metabolism: implication for HIV/AIDS therapy and utility of efavirenz as a substrate marker of CYP2B6 catalytic activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306:287–300. 10.1124/jpet.103.049601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breen RA, Swaden L, Ballinger J, Lipman MC. 2006. Tuberculosis and HIV co-infection: a practical therapeutic approach. Drugs 66:2299–2308. 10.2165/00003495-200666180-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manosuthi W, Sungkanuparph S, Tantanathip P, Lueangniyomkul A, Mankatitham W, Prasithsirskul W, Burapatarawong S, Thongyen S, Likanonsakul S, Thawornwa U, Prommool V, Ruxrungtham K, Team NRS. 2009. A randomized trial comparing plasma drug concentrations and efficacies between 2 nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor-based regimens in HIV-infected patients receiving rifampicin: the N2R study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1752–1759. 10.1086/599114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet M, Bhatt N, Baudin E, Silva C, Michon C, Taburet AM, Ciaffi L, Sobry A, Bastos R, Nunes E, Rouzioux C, Jani I, Calmy A, CARINEMO study group 2013. Nevirapine versus efavirenz for patients co-infected with HIV and tuberculosis: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:303–312. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manosuthi W, Kiertiburanakul S, Sungkanuparph S, Ruxrungtham K, Vibhagool A, Rattanasiri S, Thakkinstian A. 2006. Efavirenz 600 mg/day versus efavirenz 800 mg/day in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis receiving rifampicin: 48 weeks results. AIDS 20:131–132. 10.1097/01.aids.0000196181.18916.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manosuthi W, Sungkanuparph S, Thakkinstian A, Vibhagool A, Kiertiburanakul S, Rattanasiri S, Prasithsirikul W, Sankote J, Mahanontharit A, Ruxrungtham K. 2005. Efavirenz levels and 24-week efficacy in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy and rifampicin. AIDS 19:1481–1486. 10.1097/01.aids.0000183630.27665.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. 2013. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach 2010 revision. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf Accessed 1 April 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams I, Churchill D, Anderson J, Boffito M, Bower M, Cairns G, Cwynarski K, Edwards S, Fidler S, Fisher M, Freedman A, Geretti AM, Gilleece Y, Horne R, Johnson M, Khoo S, Leen C, Marshall N, Nelson M, Orkin C, Paton N, Phillips A, Post F, Pozniak A, Sabin C, Trevelion R, Ustianowski A, Walsh J, Waters L, Wilkins E, Winston A, Youle M. 2012. British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2012. HIV Med. 13(Suppl 2):1–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michaud V, Bar-Magen T, Turgeon J, Flockhart D, Desta Z, Wainberg MA. 2012. The dual role of pharmacogenetics in HIV treatment: mutations and polymorphisms regulating antiretroviral drug resistance and disposition. Pharmacol. Rev. 64:803–833. 10.1124/pr.111.005553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durant J, Clevenbergh P, Garraffo R, Halfon P, Icard S, Del Giudice P, Montagne N, Schapiro JM, Dellamonica P. 2000. Importance of protease inhibitor plasma levels in HIV-infected patients treated with genotypic-guided therapy: pharmacological data from the Viradapt study. AIDS 14:1333–1339. 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabbiani M, Bracciale L, Ragazzoni E, Santangelo R, Cattani P, Di Giambenedetto S, Fadda G, Navarra P, Cauda R, De Luca A. 2011. Relationship between antiretroviral plasma concentration and emergence of HIV-1 resistance mutations at treatment failure. Infection 39:563–569. 10.1007/s15010-011-0183-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marzolini C, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Greub G, Biollaz J, Buclin T. 2001. Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 15:71–75. 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manosuthi W, Sukasem C, Lueangniyomkul A, Mankatitham W, Thongyen S, Nilkamhang S, Manosuthi S, Sungkanuparph S. 2013. Impact of pharmacogenetic markers of CYP2B6, clinical factors, and drug-drug interaction on efavirenz concentrations in HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1019–1024. 10.1128/AAC.02023-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotger M, Tegude H, Colombo S, Cavassini M, Furrer H, Decosterd L, Blievernicht J, Saussele T, Gunthard HF, Schwab M, Eichelbaum M, Telenti A, Zanger UM. 2007. Predictive value of known and novel alleles of CYP2B6 for efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-infected individuals. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 81:557–566. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatanaga H, Hayashida T, Tsuchiya K, Yoshino M, Kuwahara T, Tsukada H, Fujimoto K, Sato I, Ueda M, Horiba M, Hamaguchi M, Yamamoto M, Takata N, Kimura A, Koike T, Gejyo F, Matsushita S, Shirasaka T, Kimura S, Oka S. 2007. Successful efavirenz dose reduction in HIV type 1-infected individuals with cytochrome P450 2B6 *6 and *26. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:1230–1237. 10.1086/522175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukasem C, Cressey TR, Prapaithong P, Tawon Y, Pasomsub E, Srichunrusami C, Jantararoungtong T, Lallement M, Chantratita W. 2012. Pharmacogenetic markers of CYP2B6 associated with efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-1 infected Thai adults. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74:1005–1012. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04288.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stahle L, Moberg L, Svensson JO, Sonnerborg A. 2004. Efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients: inter- and intraindividual variability and clinical effects. Ther. Drug Monit. 26:267–270. 10.1097/00007691-200406000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arab-Alameddine M, Di Iulio J, Buclin T, Rotger M, Lubomirov R, Cavassini M, Fayet A, Decosterd LA, Eap CB, Biollaz J, Telenti A, Csajka C, Swiss HIVCS 2009. Pharmacogenetics-based population pharmacokinetic analysis of efavirenz in HIV-1-infected individuals. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 85:485–494. 10.1038/clpt.2008.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabrera SE, Santos D, Valverde MP, Dominguez-Gil A, Gonzalez F, Luna G, Garcia MJ. 2009. Influence of the cytochrome P450 2B6 genotype on population pharmacokinetics of efavirenz in human immunodeficiency virus patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2791–2798. 10.1128/AAC.01537-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsch MS, Gunthard HF, Schapiro JM, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Hammer SM, Johnson VA, Kuritzkes DR, Mellors JW, Pillay D, Yeni PG, Jacobsen DM, Richman DD. 2008. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection: 2008 recommendations of an International AIDS Society-U. S. A. panel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:266–285. 10.1086/589297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manosuthi W, Sungkanuparph S, Tantanathip P, Mankatitham W, Lueangniyomkul A, Thongyen S, Eampokarap B, Uttayamakul S, Suwanvattana P, Kaewsaard S, Ruxrungtham K, Team NRS. 2009. Body weight cutoff for daily dosage of efavirenz and 60-week efficacy of efavirenz-based regimen in human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfected patients receiving rifampin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4545–4548. 10.1128/AAC.00492-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedland G, Khoo S, Jack C, Lalloo U. 2006. Administration of efavirenz (600 mg/day) with rifampicin results in highly variable levels but excellent clinical outcomes in patients treated for tuberculosis and HIV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1299–1302. 10.1093/jac/dkl399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matteelli A, Regazzi M, Villani P, De Iaco G, Cusato M, Carvalho AC, Caligaris S, Tomasoni L, Manfrin M, Capone S, Carosi G. 2007. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of efavirenz with and without the use of rifampicin in HIV-positive patients. Curr. HIV Res. 5:349–353. 10.2174/157016207780636588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwara A, Lartey M, Sagoe KW, Kenu E, Court MH. 2009. CYP2B6, CYP2A6 and UGT2B7 genetic polymorphisms are predictors of efavirenz mid-dose concentration in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 23:2101–2106. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283319908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]