Abstract

Solutions to complex health and environmental issues experienced by First Nations communities in Canada require the adoption of collaborative modes of research. The traditional “helicopter” approach to research applied in communities has led to disenchantment on the part of First Nations people and has impeded their willingness to participate in research. University researchers have tended to develop projects without community input and to adopt short term approaches to the entire process, perhaps a reflection of granting and publication cycles and other realities of academia. Researchers often enter communities, collect data without respect for local culture, and then exit, having had little or no community interaction or consideration of how results generated could benefit communities or lead to sustainable solutions. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has emerged as an alternative to the helicopter approach and is promoted here as a method to research that will meet the objectives of both First Nations and research communities. CBPR is a collaborative approach that equitably involves all partners in the research process. Although the benefits of CBPR have been recognized by segments of the University research community, there exists a need for comprehensive changes in approaches to First Nations centered research, and additional guidance to researchers on how to establish respectful and productive partnerships with First Nations communities beyond a single funded research project. This article provides a brief overview of ethical guidelines developed for researchers planning studies involving Aboriginal people as well as the historical context and principles of CBPR. A framework for building research partnerships with First Nations communities that incorporates and builds upon the guidelines and principles of CBPR is then presented. The framework was based on 10 years’ experience working with First Nations communities in Saskatchewan. The framework for research partnership is composed of five phases. They are categorized as the pre-research, community consultation, community entry, research and research dissemination phases. These phases are cyclical, non-linear and interconnected. Elements of, and opportunities for, exploration, discussion, engagement, consultation, relationship building, partnership development, community involvement, and information sharing are key components of the five phases within the framework. The phases and elements within this proposed framework have been utilized to build and implement sustainable collaborative environmental health research projects with Saskatchewan First Nations communities.

Keywords: Saskatchewan first nations, community-based participatory research, framework, engagement, consultation, ethical partnership

Introduction

It is well established that the “helicopter” approach to research in First Nations communities has, unwittingly, contributed to discordance with First Nations people and a barrier to participation in standard traditional research processes that are not based on participatory practices.1–3 Utilizing a helicopter approach, researchers often turn to communities to recruit research subjects or to conduct studies on communities, or individuals within them, that are designed and based entirely on the researcher’s area of expertise.1,4 In this arguably failed approach, researchers develop projects without community input, collect data without the full knowledge and consent of participants, seldom share findings, and almost never create mechanisms to continue successful research projects or programs that would greatly inform public health and environmental policy development. The traditional approach naturally thwarts community involvement in the research process as it leaves community members feeling rather like guinea pigs, and a collective impression of communities that they are rather like anthills being observed through a magnifying glass, merely subjects of research studies, used simply as information sources, who receive little benefit.

Within the last two decades, American and Canadian scholars, members of various research and non-research focused organizations, academic institutions, research funding agencies, and First Nations Health Associations have developed several research guidelines with the goal of providing ethical guidance to researchers intending to work with Aboriginal communities. Community-based participatory research (CBPR), a method to research supported by many Aboriginal communities, has also emerged as an alternative to the helicopter approach. CBPR originates from the amalgamation of action and participatory research; research approaches both rooted in the disciplines of social science and education.5,6 Recognized ethical research guidelines and CBPR share many concepts and continue to evolve through modifications over time. In this article a brief outline of established guiding research principles are presented in reference to author, organization and approximate timeline of development. A short discussion on the historical context and key guiding principles of CBPR are then highlighted. Subsequently, a framework for building research partnerships with First Nations communities that developed between researchers and First Nations communities in Saskatchewan is proposed. The framework attempts to addresses helicopter approaches to research, builds upon acknowledged ethical guidelines and principles of CBPR, and provides further guidance for researchers intending to work with First Nations communities.

Established Research Guidelines: Ethical Alternatives to the “Helicopter” Approach

Indigenous scholars

One of the first scholarly responses to this drop-in-drop-out research approach was published in 1993 and developed for academics of American and Canadian institutions intending to conduct studies involving American Indians and Aboriginal people.7 Devon Mihesuah, an American scholar and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma developed one of the earliest of these guidelines. Mihesuah’s 10 guidelines, which stress the importance of consultation with, and approval of, research proposals by elected political leadership in communities, are still relevant and applicable today. Mihesuah’s guidelines advocate for clear communication between researchers and community partners in order to facilitate thorough understanding of all study aspects and the anticipated consequences of research findings on communities or individuals. One of the principles underlying these guidelines is assurance of a fair and appropriate return on investment to participating individuals and communities alike. Another scholarly work worthy of note is the textbook, Decolonizing Methodologies, written by Tuhiwai Smith, which addresses the Western research concept and its application to indigenous peoples on a global scale.8 Smith recommends that indigenous peoples and scholars work collaboratively to establish research priorities, ethical codes and agreements, roles and responsibilities for all parties, and mutually agreeable investigative methodologies. Smith also highlights the ethic that research must be framed and analyzed within historical, political, and cultural contexts. Indigenous scholars continue to move toward the development of an indigenous research paradigm; an approach to research that stems from indigenous people’s roots, values, and principles.9–11

Canadian organizations

Owing to the growing recognition of a set of guidelines for the ethical conduct of research involving Aboriginal peoples in Canada, several published documents were developed by various organizations over the past two decades. The Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies, the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), and the Canadian Archaeological Association have developed and published guidelines in various reports.12–14 In 1996, Kowalsky et al., developed guidelines for respectful entry into Aboriginal communities,15 however it is argued here that although these exhibited a degree of cultural sensitivity, they forgo the necessary consultation and engagement steps in research development that are presented here in this paper as absolutely essential building blocks to successful First Nations community-based research partnerships.

The Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (SIFC), now the First Nations University of Canada (FNUC), published a brief in 2002 that called for a paradigm shift in Aboriginal research. The brief highlighted the general agreement between the recommendations put forward by RCAP and the principles established in the above mentioned reports. It states “the solution to the costs of social problems facing indigenous peoples is the need to shift the research paradigm from one in which outsiders seek solutions to ‘the Indian problem’ to one in which indigenous people conduct research and facilitate solutions themselves.”16 Essentially, this recognized that traditions and knowledge held by Aboriginal Elders should be respected, that Aboriginal communities should benefit directly from research findings, and that a commitment to build a cadre of Aboriginal scholars to take on work related to research activities be incorporated under the new research paradigm.16

Canadian tri-council funding agencies

In 2002–03, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) launched a multi-stage public dialog on research and Aboriginal peoples with a diverse group of stakeholders interested in research on, for, by, and with Aboriginal peoples. The dialog resulted in a report, Opportunities in Aboriginal Research, which presented sound evidence for the need to move away from research “on and for” Aboriginal peoples, to research “by and with” Aboriginal peoples.17 To promote the ethical conduct of research involving humans, Canada’s three federal research agencies—the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the SSHRC, developed a joint policy referred to as the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS).18 The TCPS policy, initially adopted in 1998, contained a very brief statement and a list of practices for the consideration of researchers conducting studies involving Aboriginal peoples. In 2010, TCPS 2, a second version of the policy containing a more comprehensive framework for the ethical conduct of research involving Aboriginal peoples was adopted, and ultimately replaced the original TCPS.19 The framework, outlined in Chapter 9 of this document, was developed for the purpose of ensuring that research involving Aboriginal peoples is premised on respectful relationships, as well as fuller collaboration and engagement between researchers and participants. Though these developments helped refine ethical principles, operational frameworks focused on achieving the goals of CBPR with First Nations communities requires growth and advancement.

First Nations

A further refinement came with ethical research guidelines derived specifically from a First Nations context, known as the First Nations Principles of OCAP (ownership, control, access and possession) as published by Schnarch in 2004.3 The OCAP principles were developed by the Steering Committee of the First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, and were developed as a political response to what were perceived as persistent colonial approaches to research and information management.3 The fundamental additional principle of OCAP is the application of self-determination to the research process. This key concept relates to First Nations’ collective ownership, control, management, access, and physical possession of information that is generated through academic and government research. First Nations would have in their possession, for the first time in history, a full ownership of research parameters such as monitoring, surveillance, surveys, statistics, as well as an opportunity to assert a vast and hitherto unappreciated cultural knowledge of nature and sociology. In essence, OCAP provides the opportunity for First Nations to make decisions regarding why, how, and by whom research information is collected, utilized, and disseminated. OCAP principles may be viewed by some researchers as impediments to the ability to meet timelines for publication and dissemination required by academic institutions and granting agencies. While both the perception and realities of such impediments can be resolved with effective mechanisms of engagement, there is a need for academic institutions to recognize the benefit of time and effort devoted to engagement by researchers, and its ultimate impact on quality and sustainability of research endeavors with First Nations.

It is evident that the many calls within the various guidelines developed for the ethical conduct of research involving Aboriginal peoples are clear and gives distinct messages to academia and government alike to adopt more collaborative and participatory strategies for conducting research.

Research with Community Participation

Participatory and participatory action research (PAR): a historical look

It is important to acknowledge that the issues surrounding relationships relevant to academic and government research exist in many community contexts not exclusive to First Nations, and the development of the principles discussed above are overlaid historically by concepts of action research (AR), participatory research, and PAR in a number of areas. The concept of AR has often been attributed to Lewin, who first published the term in 1946.20 Lewin rejected the positivist view of science and brought researchers and community members together as co-partners in research.5 Participatory research evolved from work in Latin America, Asia, and Africa as a move toward transforming oppressed societies through experiential knowledge.5 Participatory research was influenced by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire21 who proposed that a central objective for transformative action involved developing a critical consciousness of social, political, and economic contradictions, such that individuals in communities could take action against oppression. In Freire’s alternative approach to research, education and research occur in a cultural cycle and are based within, and linked to, community needs. PAR, a term coined by Orlando Fals Borda, originates from the application of liberation pedagogy within the context of Latin American adult education in the 1960s.5 It is characterized by research, education, and social action. Budd Hall, a Torontonian, was acknowledged for bringing participatory research to Canada.5

PAR has been utilized in a wide variety of applications since the 1940s. It has been employed in administration,22 community development,20 organizational change,23 and teaching.24,25 In the 1970s, participatory strategies were primarily applied to research and practice used in international development projects. These projects were often initiated in developing countries by international agencies and non-governmental organizations, and focused on the transfer of technological knowledge from expert to community and designed to facilitate greater community networking.26

Present day participatory research

Today, participatory research techniques have evolved in the fields of education, public health, community health promotion, natural resource management, and environmental health.27–30 Under various monikers, PAR, community-based, community oriented and CBPR have materialized as participatory approaches applied in the context of understanding human–ecosystem relationships, improvement of primary care delivery, and the development of environmental health indicators.27,31–33 Although the terms given to current approaches differ, the overall intent for the development of these strategies was primarily to address the failure of traditional research approaches that proved to be unsatisfactory to individuals and communities. The history associated with Indigenous peoples research is commonly characterized by failure to provide benefit, transfer skills and knowledge, or to effectively inform community, public health, and governance, and alienation of individuals and communities. In general, participatory research approaches involve forms of investigation where researchers and the researched population form collaborative relations to identify and address mutually conceived issues through phases of action and research.33

CBPR principles: a new research paradigm

CBPR has emerged as an alternative to the helicopter approach and is a method to research supported by many First Nations communities.3 Table 1 provides a summary of the main differences between a traditional research approach and a CBPR approach. CBPR encompasses many of the concepts of PAR, the ethical principles outlined in OCAP, and both American and Canadian guidance documents. CBPR emphasizes the development of genuine partnerships between communities and external researchers. It begins with a subject of real concern to the community, identifies, and builds on unique strengths and contributions of each partner, and equitably involves all partners in the research process.34,35 It is dedicated to building community capacity and balances research and action. It is an approach to research where translation and utilization of research findings occurs throughout the research process.35,36 Although the benefits and approaches of CBPR have been recognized by some segments of the broader university-based research community, there exists a fundamental need for changes in our approaches to First Nations centered research, and for additional guidance to researchers on how to establish respectful and productive partnerships with First Nations communities beyond a single funded research project. To this date, researchers from academic and governmental institutions are still formulating research projects without community input and subsequently seeking partnership to conduct the research proposed on First Nations communities instead of with communities. With the growing recognition for a new Aboriginal research paradigm and the increasing use of CBPR, there is a necessity for greater understanding, but not necessarily standardization, of the process for developing long-lasting and meaningful research partnerships with First Nations communities. Over a 10 year period of conducting collaborative research with First Nations communities in Saskatchewan, a framework for developing sustainable, beneficial, and meaningful research partnerships with Saskatchewan First Nations communities has evolved and will be outlined here.

Table 1.

Comparison of traditional and community-based participatory research.

| TRADITIONAL RESEARCH APPROACH | COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH |

|---|---|

| Expert derives research problem, purpose objectives and questions | Community works with investigator to identify and develop research problem, purpose, objectives and questions |

| Research conducted in or on community | Research conducted in full partnership with community |

| No community assistance or collaboration | Community members are participants and collaborators |

| Researcher advances own knowledge and discipline | Co-learning and capacity building among researchers and community partners |

| Researchers control research activity, resources, data collection and interpretation | Equitable control of research activity, resources, data collection and interpretation among researchers and community partners |

| Researchers own, control, access, possess, use and disseminate data | Research data is shared and researchers and communities come to a joint decision on its use and dissemination |

| Research goal: Knowledge production for publication, academic advancement, | Research goal: Knowledge production to meet needs, benefit and inform action for change. |

Notes: This table demonstrates the main differences between a traditional research approach and a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach. This table was adapted from Mary Anne MacDonald, MA, DrPH from Duke Center for Community Research http://www.dtmi.duke.edu/dccr/community-linked-research/. Accessed at http://ccts.osu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Practicing%20Community-engaged%20Research_Training%20Module.pdf

Setting of Research Partnership Development

Research partnerships were established in Saskatchewan, Canada, between researchers from the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) and members of First Nations communities. Saskatchewan, a province centrally located in Canada, is home to 74 First Nations communities, representing five distinct linguistic cultures of Cree, Dene, Dakota, Nakota, and Saulteux. The registered Indian population is approximately 129,138. Sixty-three communities are affiliated with the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations (FSIN) and 11 have no affiliation. The FSIN is the representative body of all Saskatchewan’s First Nations, committed to honoring the spirit and intent of the provincial treaties struck during the 1870s. There are 10 Tribal Councils to which some communities are affiliated. Tribal Councils are mainly political organizations but also administer community programs and services to member communities. For example the Saskatoon Tribal Council (STC) is composed of seven autonomous member nations; governed by their own Chief and Council, laws and customs and located within a 200 km radius of the city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Jointly STC represents approximately 11,000 First Nations people and provides advisory services in areas of economic development, financial management, community planning, technical services and band governance.

Research partnerships were initially established in 2004 between four member nations of the Saskatoon Tribal Council (STC), and researchers from the University of Saskatchewan, First Nations University of Canada, and the Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC). The initial research partnership originated as a consequence of STC member communities’ interest in assessing the impacts of solid waste disposal practices on environmental health in their communities. Representatives of the STC approached the SRC Aboriginal Liasion Officer with community concerns, and collectively, a team of researchers and community partners were assembled to establish the research direction for the waste disposal project.

During initial project discussions, community members expressed dissatisfaction about research approaches applied in past research projects. Research projects were still being designed and implemented without prior meaningful discussions with communities. The pre-research phase, a key foundational step of research partnership development, was being bypassed. Thus a framework for conducting research with First Nations was developed to guide partnership development between Saskatchewan First Nations and researchers intending to work with these communities.

The First Nations Centered Research Framework

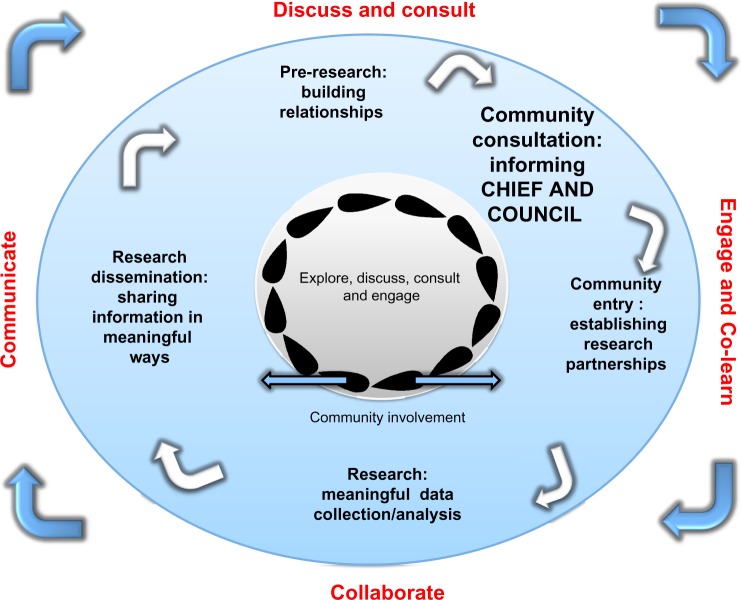

The framework for building research partnerships with First Nations communities was developed through 10 years of research engagement. The framework is composed of five phases. These phases are categorized as the pre-research, community consultation, community entry, research and research disseminations phases. The phases are cyclical, non-linear and interconnected. Figure 1 summarizes the phases of the framework proposed here. Elements of, and opportunities for, exploration, discussion, engagement, consultation, relationship building, partnership development, community involvement, and information sharing are key components within the five phases of the framework. The key elements and phases are described in the following sections of this article.

Figure 1.

The First Nations centered research framework.

The framework consists of five phases. These are represented in the light blue circle and can be read in a clockwise direction starting with the pre-research phase. The framework is centered and built upon key elements of discussion, consultation, engagement, co-learning, collaboration and communication which are depicted in red font and encompass the phases of the framework.

Phases and Elements of the First Nations Centered Research Framework

The pre-research phase: establishment of a forum for discussion

Exploring common research interests: discussion, engagement, building relationships, and partnerships

A pre-research phase, where opportunities to learn, share information, identify common research pursuits, and explore potential research partnerships between First Nations and interested academics, students, and researchers was recognized as an important first stage of the First Nations centered research framework. A forum for discussion was initially created through the development of an Environmental Health Working Group (EHWG). The EHWG, an ad-hoc group, was essentially established as a mechanism to facilitate continuous face to face engagement and dialogue between original and established partners. The EHWG was established in 2006 following the development of key relationships built in 2004 between members of the STC, SRC, and U of S. An extension of these relationships was then made to representatives of the Health and Social Development Secretariat (HSDS) of the FSIN and the Indigenous Peoples Health Research Centre (IPHRC) and to members of the broader academic and First Nations communities.

The EHWG meetings were held monthly at the University and discussions took place on various topics related to environmental contamination, health services and delivery, science education in Saskatchewan First Nations communities, sources of research funding, safe drinking water supplies, and processes for community engagement.

Within a year, the EHWG transformed into the First Nations Environmental Working Group (FNEHWG), a formal group under the mandate of the Health and Social Secretariat of the FSIN. This group, still active today and chaired by the Policy Analyst of the HSDS, provides a forum for widespread discussion with representatives of the 74 Saskatchewan First Nations. The FNEHWG meets approximately four times per year. Members include the original small group of partners, representatives from Health Canada, the 10 Tribal Councils as well as environmental health directors, public works and water treatment plant operators of the representative First Nations communities. This larger forum provides group members the opportunity to listen and voice environmental health issues, share data related to ongoing projects and identify future research priorities and funding opportunities. The FNEHWG also generates occasions to invite researchers to pitch and gage interest in potential research ideas. For example a dog population management and bite prevention project was recently launched through the FNEHWG. The FNEHWG is essentially a mechanism to facilitate discussion and engagement between researchers and community members prior to research project development. It also creates a gateway to establish research networks and relationships. This forum for discussion has provided opportunities for researchers and community members to engage in productive, meaningful and respectful conversations, develop long-term friendships and sustained research partnerships.

First Nations Environmental Health Working Group meetings have led to the initiation of several research projects on topics related to community health, water regulations, drinking water supply, access, safety, and environmental contamination. Research projects have involved research partnerships between academics and a single or several First Nations. Broad scale projects have involved partnerships with academics and representatives of the HSDS of the FSIN, where all 74 communities engaged in research activity. Members of the FSIN, the HSDS, and the FNEHWG are also affiliated with a provincially funded and formally recognized University research group; the Safe Water for Health Research Team and act as advisors to this team (http://shrf.ca/Recipient?recipID=2780).

In summary, the pre-research phase involves exploring common research interests, building relationships and research partnerships through continuous discussion and engagement between researchers and community members. This phase involves developing opportunities to share knowledge, foster dialog and mutual learning. The development of a working group, such as the FNEHWG, is one forum that creates an ethical space (37) where research ideas are shared, developed, modified and implemented. The pre-research phase involves an enormous commitment to long-term communication, and an investment of time, on the part of the researcher and the community members. For example, discussion among researchers, students, and community members about a research project aimed at exploring the challenges and barriers to water regulation in First Nations communities occurred over a three-year period prior to the implementation of any research activities.

Community consultation phase: informing Chief and Council

Initial community consultations with Chief and Council

The Community Consultation phase of the framework involves an extension of discussion, engagement, and consultation with the Chief and Council of a First Nation potentially interested in establishing a research partnership. Consultative processes with Chief and Council differ depending on the breadth of the research partnership and the purpose of the research project. For example, research projects developed in collaboration with members of the HSDS of the FSIN must be presented to, evaluated, and approved by the FSIN senior technical advisory group (STAG) prior to consultation with Chief and Council of individual First Nation Communities. The STAG is an FSIN led advisory body consisting of First Nations Health Directors and representatives from the 10 Tribal Councils and 11 Independent First Nations. This body meets quarterly and advises the FSIN HSDS on policy, advocacy, and priorities of both federal and provincial governments as well as academic research with First Nations. They provide a very important role in advisory on many issues and make recommendations as necessary to the Health and Social Development Commission (HSDC) Chiefs. Issues of broader context are addressed by the HSDC at the FSIN All Chiefs Legislative Assembly.

Research projects that receive STAG approval are shared by the STAG member with the Chief and Council in their respective communities. Chief and Council members, once informed of research activities, discuss whether research in the particular area is worth pursuing within their respective communities. Chief and Council inform STAG members of their approval to move forward with a research partnership. Subsequently, numerous follow-up face to face discussions between the researchers and the STAG liaison occur prior to a formal meeting in the community with Chief and Council. The STAG members effectively act as liaisons between the researcher and Chief and Council. They provide essential guidance on community entry, consultative processes with Chief and Council, research activity and ethical and cultural protocols. Research projects, although already established through consultation with the FSIN-HSDS, are modified to meet individual community objectives and goals.

Alternatively, consultative processes between researchers and Chief and Council, are initiated by individual community members outside the STAG advisory. This process is typically initiated following several discussions and engagement between researchers and community members at meetings of the FSIN-EHWG, workshops, conferences, or other relevant networking venues. The process of informing Chief and Council is similar to that of the STAG liaison. The main difference here is that a research idea is shared with Chief and Council not a research project. For example, research on the topic of drinking water supply, discussed initially at a FSIN-EHWG meeting, was presented to Chief and Council by the communities Educational Director. Subsequently, the Educational Director took on the role as a liaison between the researcher and the Chief and Council.

Once the Chief and Council have considered the research project or topic and discussion and subsequent follow-up between the liaison and researcher have occurred, a formal meeting in the community is arranged by the STAG or community liaison.

Community entry: consultation and establishment of research partnership

Consultation with Chief and Council: research partnership and planning

Community entry is a phase that involves the direct consultation between the researcher(s) and Chief and Council members within the community. This initial meeting is arranged to allow the researcher(s) and Chief and Council members to share areas of expertise, perspectives on the research problem, and the goals and objectives of the research. It also provides the opportunity to discuss cultural, traditional, and western scientific protocols. Subsequent meetings between the researcher(s) and Chief and Council take place until all parties are satisfied and mutually agree upon research goals, objectives, methods, logistics, outcomes, and ethical considerations. Consultations between researcher and Chief and Council can occur over several weeks or months depending on the project, individual timelines, project logistics and ethical concerns. These subsequent meetings facilitate understanding of community protocol and the bridging of cultural knowledge into the planning, methodology, participant recruitment, and capacity building strategies of the research agenda. Thus, research is conducted in accordance with the culture and customs of the First Nation.

Data collection, analysis, sharing, storage, and dissemination are discussed in consultation with Chief and Council. As outlined in the principles of OCAP, First Nations communities have the right to own, control access, and possess data collected in their community. Thus, the First Nations centered research framework supports OCAP principles. This means that data collected within a First Nation community, in any form, is kept by the First Nation. Data is collaboratively analyzed between the research partners. This process is beyond the scope of the paper, but involves multiple stages of engagement, consultation, planning co-learning, and the co-interpretation of research results. Publications that arise from research conducted with the communities include the First Nation, or a representative thereof, as co-authors. Researchers seek permission from the community before utilizing data for the purpose of publication and conference presentations and seek opportunities to co-present, co-author, and co-publish work with members of the community.

The Chief and Council approve project timelines and appropriate protocols typical for their community and appoint individuals, community research advisors, to assist with project logistics. This again involves in-depth engagement, respectful dialogue, and equity in decisions around the scope of the project, its aims and goals, questions, hypotheses, and methodologies as well as the modes of dissemination. Ultimately, through this consultative process, as part of the community entry phase of the framework, a full research partnership, based on trust, respect, and understanding of respective worldviews and values is achieved. The leadership and community approve the collaborative research project and the research activity is initiated.

In some communities, written research agreements between the Chief and Council and the researcher are formulated. These agreements set out the ethical principles guiding the research partnership and the research purpose and scope, the methodology and data collection procedures, and the funding supporting the research endeavour. The roles and responsibilities of research partners, the expected outcomes of the research and the modes and forms of dissemination are also outlined in the research agreeement. In some instances, written agreements are not formulated, but rather regular consultations with, and updates to, Chief and Council throughout the research activity function to guide and inform the research relationship.

Community advisors liaise and communicate on a regular basis with researchers and monitor the implementation of the principles and progress of the research relationship. Ethical approval is sought at both the community and university levels through appropriate processes. In some cases, the research partnership has evolved through several years of discussion and various levels of engagement. Thus, the ethical considerations are often articulated within the funding proposal developed in collaboration with the community.

A community meal or celebration at the school is often planned as the initiating event supportive of the research endeavor and is a means to kick off a project in “the right way.” Pipe ceremonies have also been proposed as a means of celebration and acceptance for, and initiation of, a research project in the communities. Community gatherings are intended to introduce the research team to the community, review the research project activities, and engage with the community within their context. The academic research team works in partnership with the community advisor to ensure this meeting provides the community with information on the nature of the research and its potential meaning and impact to the community, and to respond to any questions or ethical concerns. It also provides the opportunity for the academic research team to develop ongoing linkages with the community within and following the time-frame of the proposed research.

Research phase: gathering data meaningful and beneficial to communities

Initiation of research and community involvement

In this phase of the framework, research activity is initiated. The community remains involved in the research activity throughout the research project, from its initial design to achievement of outcomes. As a first step, community research assistants (CRAs) and graduate students are hired. Together, the CRAs and graduate students attend a research orientation session. This session is generally held in the community and is aimed to inform and guide research activities. Graduate students and CRAs work as a team to collect research information. They meet and communicate with the Community Advisor on a regular basis to establish linkages with community members and ensure equitable participation among genders and age groups (Elders and youth). They also discuss logistical aspects of the research project (eg, timelines, data, collection/management, dissemination) and inform the Community Advisor of any ethical issues or concerns. Thus a continuous cycle of communication occurs between partners throughout the research process.

Community youth, attending high school or returning to college or university, have been employed on projects as CRAs. Community members seeking part- or full-time employment are also hired to assist in research activities. In one particular case, a CRA, conducting water sampling and analysis for a particular project assessing drinking water quality, was subsequently hired into a full-time position at the U of S. Elders and children’s involvement in research activity is respected. In several projects, Elders have provided the necessary and essential guidance to frame research activity in the historical, social, political and cultural context. Children have been involved in educational aspects of research activity through creating connections with community Elders, teachers working in the community schools as well as university students.

Research dissemination phase: communicating results

Sharing information in meaningful ways: action for change

Data collected with the community must be shared and utilized in ways that are meaningful and beneficial to the community. Approval processes for use and dissemination of community information are discussed within several of the early phases of this research framework, but are essentially established in the community entry phase of the framework. In general, it is understood that results are utilized and shared according to mutually agreed upon research purposes and data sharing principles. Reports and journal articles are co-authored with designated representatives. The participation and assistance of community members is acknowledged in all forms and levels of data sharing.

There are various ways and manners to communicate research results, however, opportunities for verbal communication of results are meaningful and often well received at the level of the community. In projects to date, data has generally been shared verbally with community members at organized community events (Treaty Days, a community meal or prearranged workshop or research related events). Verbal communication of research results have also been shared at Chief and Council meetings and when granted permission, verbal sharing of information has extended to Tribal Council meetings, the FSIN-EHWG, STAG Advisory, Aboriginal Television Network and Radio, regional and national conferences and organized workshops. The extension of information to larger venues is valuable for sharing processes related to research partnership development, methodologies and activities. These venues also provide opportunity to share capacity building strategies and give greater voice to environmental health issues at the local, regional and national levels.

Research results are also meaningful in the form of written reports. For example, reported results of a drinking water quality assessment have been utilized to inform community drinking water management and to acquire funding for drinking water infrastructure. Co-authored publications, posters, and conference presentations are forms of dissemination accepted by research parties to collaboratively communicate results to the broader public, government, and academic audience. The FNEHWG meetings are a place for engagement and discussion, but are also a place where dissemination activities and forums were conceived. For example a jointly organized, CIHR-funded workshop on Water and Health in Indigenous Communities, that brought together Indigenous peoples from Peru and Saskatchewan, was developed and organized, through conversations at these meetings. Joint attendance and co-presentation with community representatives at National and Regional First Nations-led conferences have also resulted through the engagement processes essential to this research partnership building framework. For example, presentations at the Canadian Aboriginal Science and Technology Society conferences, and conferences organized by the Tribal council and the FSIN had their foundations in the pre-research phase of this framework.

Relevance of the First Nations centered research framework

The First Nations Centered Research Framework creates a process for long-term meaningful research partnerships to develop as a consequence and natural extension of foundational cyclical and evolutionary courses of community engagement. Minkler and Hancock38 state that the most effective, beneficial, and meaningful CBPR relationships, are those that are built on effective engagement with communities.

Aboriginal communities are not homogenous and not uniformly affected by their environmental, social, and economic situations.39 Canada’s Aboriginal people are exceptionally diverse in many respects, including culturally, linguistically, socially, economically, and historically. The recognition and acceptance of such diversity is essential for research partnership development. An understanding of such diversity can only be acquired through direct discussion, communication and engagement with First Nations people. First Nations communities have differing views on research outcomes, levels of community partnership and involvement, capacity building, interest, and commitment to the research process and activity. For example in one project, a diverse group and number of community members (Chief and Council, Elders, Youth, and broader community) were involved in research related activities related to water and health while in another community, involved in the same project, appointed community representatives were only involved. Although the framework for research partnership advancement may appear in some ways uncomplicated, it is a guide, amenable to adaptation to meet community needs as well as the holistic nature of research with First Nations communities. This framework is not intended to convey a standardized approach for establishing research partnerships with First Nations.

This framework challenges researchers to consider their motivation for engagement. It challenges researchers to confront values of individualism, egocentrism, competition, hierarchy, material success and personal achievement. Values, generally supportive of individual faculty success in academic institutions, but entirely inconsistent with First Nation traditional values. The framework challenges researchers to embrace and value the inclusion of First Nations knowledge, experience, expertise, culture, tradition, and methodologies into the research process. It also confronts researchers to reflect upon and understand the historical context of First Nations people within Canada, and familiarize themselves on how this history contributes to the current political, health, socio-economic, and environmental conditions within First Nations communities. The reflection upon and understanding of this history informs a researcher’s engagement with community and provides context to the research process and activities.

In applying this framework, researchers must be willing to commit to significant time out of the university environment, and have a strong dedication to meaningful engagements with First Nations. The process of establishing research relationships with First Nations requires a careful balance of the demands of other research, graduate training, classroom teaching, and administration to meet the demands of institutional performance. The challenge of these demands should be communicated with First Nations research partners, in order to foster a mutual understanding of any limitations to engagement, communication, or research activity.

Conclusions

Indigenous communities today largely support CBPR endeavors with research institutions40 that work equitably, honestly, cooperatively, respectfully, communicatively,2 reciprocally, and patiently..

The framework presented here, inclusive of established ethical guidelines, provides a process for initiating community engagement and developing long-term research partnerships with Saskatchewan First Nations. The framework supports a collaborative approach to research, where partnerships are built among colleagues who share complementary skills, knowledge, and expertise and where equitable partnership, based on sharing responsibilities and benefits, leads to outcomes that are satisfactory to all partners. It extends general ethical requirements and calls for research that is holistic, culturally sensitive, beneficial, and significant to involved communities. It is founded on meaningful engagement built on mutual respect, trust, and understanding between partners. Research collaborations, once established, naturally transform and evolve throughout the partnership, leading to deeper and reciprocal engagement, more effective identification of issues and strategies to solve problems, and ultimately better capacity building and other outcomes. Conflicts, ethical dilemmas, and other breakdown issues become secondary once the engagement process is established. In addition, newly formed, higher level, and evidence based research directions and more extensive research programs emerge from the partnership, all informed by shared interpretation of results.

The development of successful First Nations-based participatory research programs require multiple years of discussion, consultation and engagement. The engagement process allows the time required to build friendships and develop trust and familiarity among potential research partners. It provides the time to share knowledge, learn together and create an understanding of the research issue from the academic and community perspective. Extensive consultation and engagement must develop to the point where research work can be successfully devised, performed, and completed in a fully respectful collaborative manner. Finally, it is the will, intent, and commitment for continuous engagement and respectful dialog that is foundational to the development of meaningful, long-term research partnerships. Fostering opportunities for discussion, where individuals have equitable occasion to share expertise, experiences, and knowledge provides time for cohesion between researcher and community, builds team spirit, unity, and shared aims, creates new understandings, and informs the research process.

In conclusion, meaningful and continuous communication, discussion engagement, and consultation are the indispensable elements woven into successful research partnerships with First Nations. The consultative and engagement processes inform the structure of the research in a context that ensures relevance and benefit to the community. Consultation and engagement allow the partnership to identify broader multi-dimensional factors affecting environmental and health-related research questions. The process enables communities to devise innovative community-strategies to address problems in a collaborative fashion between community and researcher. The extensive engagement and consultative processes therefore empower communities and enlightens the researchers.

Definitions

First Nation: is a term that came into common usage in the 1970s to replace the word “Indian.” The term First Nation is widely used, but no legal definition of it exists. The term “First Nations peoples” refers to the Indian peoples in Canada, both Status and non-Status. Some Indian peoples have also adopted the term “First Nation” to replace the word “band” in the name of their community (http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014642/1100100014643).

Status Indian: A person who is registered as an Indian under the Indian Act. The act sets out the requirements for determining who is an Indian for the purposes of the Indian Act (http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014642/1100100014643).

Non-Status Indian: An Indian person who is not registered as an Indian under the Indian Act (http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014642/1100100014643).

Indian Act: Canadian federal legislation, first passed in 1876, and amended several times since. It sets out certain federal government obligations and regulates the management of Indian reserve lands, Indian moneys, and other resources. Among its many provisions, the Indian Act currently requires the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development to manage certain moneys belonging to First Nations and Indian lands and to approve or disallow First Nations by-laws (http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014642/1100100014643).

The term “Aboriginal” refer to people who are the descendants of the original inhabitants of North America. The Canadian Constitution recognizes three groups of Aboriginal people—Indians, Métis, and Inuit. These are three separate peoples with unique heritages, languages, cultural practices, and spiritual beliefs (http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014642/1100100014643).

The Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations (FSIN) is a provincial governance structure and a representative body for the 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan.

Tribal Councils in Saskatchewan are political units that operate to bring together their respective First Nation communities to establish and govern based on jurisdiction, mandates, and direction from their member First Nations. Tribal Councils support their member First Nations by assisting in economic, social, educational, health, financial, and cultural goals.

Acknowledgments

Consultation and engagement with numerous people have contributed to the concepts presented in this paper and thus it is difficult to name and acknowledge each person individually with whom I have learned many lessons. I would like to respectfully thank all Elders, Youth, Chiefs and Councillors, and representatives of the FSIN, Community Leaders and members with whom I have consulted along my journey of engagement to research partnership. I would also like to recognize and thank the following funding agencies that have supported this partnership approach to research: CIHR, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, Royal Bank of Canada Community Development Award, Indigenous Peoples Health Research Centre and the National First Nations Environmental Contaminants Program and Health Canada.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACUNS

The Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies

- CAA

Canadian Archeological Association

- CBPR

Community-Based Participatory Research

- CIHR

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- EHWG

Environmental Health Working Group

- FN

First Nations

- FNEHWG

First Nations Environmental Working Group, (FNEHWG)

- FNUC

First Nations University of Canada

- FSIN

Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations

- HSDS

Health and Social Development Secretariat

- HSDC

Health and Social Development Commission

- IPHRC

Indigenous Peoples Health Research Centre

- NSERC

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- OCAP

Ownership, Control, Access and Possession

- PAR

Participatory Action Research

- RCAP

Royal Commission on Aboriginal People

- SIFC

The Saskatchewan Indian Federated College

- SSHRC

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- STAG

Senior Technical Advisory Group

- TCPS

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans

- U of S

University of Saskatchewan

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: LB. Analyzed the data: LB. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: LB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: LB. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: LB. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: LB. Made critical revisions and approved final version: LB. The author reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Timothy Kelley, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Royal Bank of Canada Community Development Award, Indigenous Peoples Health Research Centre, National First Nations Environmental Contaminants Program.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Author discloses no potential conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the author has provided signed confirmation of compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deloria V. God is Red: A Native View of Religion. Golden, CO: North American Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burhansstipanov L. Developing culturally competent community-based interventions. In: Weiner D, editor. Cancer Research Interventions Among the Medically Underserved. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing; 1999. pp. 167–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnarch B. Ownership, control access, and possession (OCAP) or self-determination applied to research: a critical analysis of contemporary First Nations research and some options for First Nations Communities. J Aborig Health. 2004;1:80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macaulay AC. Ethics of research in native communities. Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:1888–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira M, Gendron F. Community-based participatory research with traditional and indigenous communities of the Americas: historical context and future directions. Int J Crit Psychol. 2011;3(3):153–68. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanlou N, Peter E. Participatory action research: considerations for ethical review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2333–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihesuah D. Suggested guidelines for institutions with scholars who conduct research on American Indians. Am Indian Cult Res J. 1993;17(3):131–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson S. What is indigenous research methodology? Can J Native Educ. 2001;25(1):175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garroutte EM. Real Indians: Identity and the survival of Native America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart MA. Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and research: the development of an indigenous research paradigm. J Indigenous Voices Soc Work. 2010;1(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies (ACUNS) Ethical Principles for the Conduct of Research in the North. Ottawa: ACUNS; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) Appendix B: Ethical Guidelines for Research. Ottawa: RCAP; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Archaeological Association (CAA) Statement of Principles for Ethical Conduct Pertaining to Aboriginal Peoples. CAA; 1996. [Accessed May 23, 2012]. Available at http://canadianarchaeology.com/caa/statement-principles-ethical-conduct-pertaining-aboriginal-peoples. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kowalsky LO, Thurston WE, Verhoef MJ, Rutherford GE. Guidelines for entry into an aboriginal community. Can J Native Stud. 1996;16(2):267–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (SIFC) A Brief to Propose a National Indigenous Research Agenda. 2002. p. 1. caid.ca/NatindResAge2002.pdf.

- 17.McNaughton C, Rock D. Opportunities in Aboriginal Research: Results of SSHRC’s Dialogue on Research and Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tri-Council . Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS- 1): Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services; 1998. [Accessed May 24, 2012]. Available at http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/archives/tcps-eptc/Default/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tri-Council . Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS-2)-2nd Edition of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services; 2010. [Accessed May 24, 2012]. Available at http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/Default/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewin K. Action research and minority problems. J Soc Issues. 1946;2(4):34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freire P. Pedagogia do Oprimido. Rio de Janeiro; Pase Terra: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke B. A new continuity with colonial administration: participation in development management. Third World Q. 2003;24(1):47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lippitt R, Watson J, Westley B. The Dynamics of Planned Change. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corey SM. Action research, fundamental research and educational practices. Teachers Coll Rec. 1949;50(8):509–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellack A, Corey SM, Doll RC, et al. Action research in schools: a panel discussion. Teachers Coll Rec. 1953;54(5):246–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whyte W. Participatory Action Research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McTaggart R. Principles of participatory actin research. Adult Educ Q. 1991;41:170. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Fremman WL, et al. Responsible Research with Communities: Participatory Research in Primary Care. North American Primary Care Research Group; 1998. [Accessed April 18, 2012]. Available at http://www.eldis.org/assets/Docs/15851.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witten and Parkes. 2000.

- 30.Yassi A, Mas P, Bonet M, et al. Applying an ecosystem approach to the determinants of health in Centro Habana. Ecosys Health. 1999;5:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parkes M, Panelli R. Integrating catchment ecosystems and community health: the value of participatory action research. Ecosys Health. 2001;7(2):85–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community Based Participation Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green LW, George MA, Daniel M, et al. Study of Participatory Research in Health Promotion. Ottawa: The Royal Society of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ermine W. The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law J. 2007;6(1):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minkler M, Hancock T. Community-driven asset identification and issue selection. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003. pp. 135–54. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldram JB, Herring DA, Young TK. Aboriginal Health in Canada: Historical, Cultural, and Epidemiological Perspectives. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]