Abstract

Ionizing radiation currently represents an important tool to generate genetic variability that does not exist in nature, especially in plants. Even so, the radiological protection still represents a subject of regulatory concern. In plants, few reports dealing with the effects of γ-rays, in terms of dose rate (rate of energy deposition) and total dose (energy absorbed per unit mass), are available. In addition, plants are known to be more radioresistant than animals. The use of ionizing radiations for studying various aspects of transcription regulation may help elucidate some of the unanswered questions regarding DNA repair in plants. Under these premises, microRNAs have emerged as molecules involved in gene regulation in response to various environmental conditions as well as in other aspects of plant development. Currently, no report on the changes in microRNAs expression patterns in response to γ-ray treatments exists in plants, even if this subject is extensively studies in human cells. The present study deals with the expression profiles of three miRNAs, namely osa-miR414, osa-miR164e and osa-miR408 and their targeted helicase genes (OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT) in response to different doses of γ-rays delivered both at low and high dose rates. The irradiated rice seeds were grown both in the presence of water and 100 mM NaCl solution. DNA damage and reactive species accumulation were registered, but no dose- or time-dependent expression was observed in response to these treatments.

Keywords: γ-ray, DNA damage, helicases, microRNAs, reactive oxygen species, relative expression

Introduction

Radiological protection of plants and animals in general, is currently a subject of regulatory concern. All living organisms exist and survive in environments where they are subjected to different degrees of radiation resulted from both natural and anthropogenic sources, including the contamination from global fallout in the atmosphere and the nuclear weapons testing. Following severe accidents (e.g., Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan 1945; Chernobyl, Ukraine 1986; Fukushima, Japan 2011), a great impact on the whole environment as well as on individual organisms and populations has been observed.

Ionizing radiation (IR) can be quantified in terms of absorbed dose (D) that is the amount of energy deposited per unit of mass. It is well known the fact that IR is currently a valuable methodology to create variability in plants.1,2 The existing literature concerns mostly the IR intervals which are useful for applications in plant breeding as well as the biological responses to high dose radiation,3,4 while relatively few strategies have used low doses to stimulate physiological processes.5-7 Recent studies on animal cells reported that the biological responses induced by low doses (LDR) are much more variable that those induced at high doses (HDR). The LDR response involves unexpected cellular processes such as non-targeted and delayed radiation effects that are in contradiction with the classical paradigm of radiation biology, which states that all radiation effects on cells are due to the direct action of radiation on DNA.8 Although the biological effects of HDR are predominantly harmful, LDR have been observed to enhance growth and survival, increase the immune response and the resistance to different stresses.9 However, the extent to which such responses may actually reduce the risks attributable to low levels of irradiation remains still to be determined.

IR can induce a large spectrum of damages and the irradiated cells have to counteract them by activating complex response pathways. These gene networks are finely regulated. In human cells it was shown that several molecular players are involved in the regulation of gene expression after irradiation, among which transcription factors10,11 and factors controlling protein synthesis, maturation and degradation.12 Additionally, in the last five years, intensive studies have focused on the role of microRNAs as molecular markers in response to γ-rays in human cancerous cells.13 MicroRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) are a group of short (21–24 nucleotides), non-coding RNAs that have emerged as important negative regulators of gene expression. It has been shown that several mRNAs can be repressed by one miRNA, illustrating redundant functions.14 These molecules are considered key players in a variety of events such as developmental and physiological processes, cell proliferation, signal transduction, stress response or pathogen invasion.15 Recent findings have demonstrated that many plant miRNAs can be induced by biotic or abiotic stress and that they play an important role in the process of adaptation to adverse environmental conditions.16,17 In humans, it was also evidenced that miRNAs are important actors in the DNA damage response.18 Since IR have such a great use in medicine, the effects and regulation pathways were intensively studied in human cells. Several studies were published also in regard to the miRNAs expression levels in response to different IR doses.19-21 Even so, little is known on several other aspects of the microRNA and mRNA-binding proteome pathways that must be further investigated in order to understand the epigenetic contributions to IR effects.13 Nonetheless the importance of these molecules in gene regulation aspects, their involvement in the response to IR was not investigated in plants. Only one study was published concerning a computational approach to identify miRNA genes induced by UV-B radiation in Arabidopsis thaliana.22

As a consequence of the scarce data related to this subject, in the present paper we investigated the expression profiles of three miRNAs, namely osa-miR414, osa-miR164e and osa-miR408, in response to different doses of γ-rays delivered both at low and high dose rates. The present miRNAs were predicted to target three putative helicase genes (OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT)23 and the computational prediction was also validated through RLM-RACE.24 Helicases are involved in a wide range of processes like recombination, replication and translation initiation, double-strand break repair, maintenance of telomere length, nucleotide excision repair, cell division and proliferation.25 Recent reports indicate that helicases are also implicated in the response to specific environmental conditions, such as temperature, light, oxygen or osmolarity.26 The present miRNAs and their targets were also shown to be responsive to early-induced salinity stress conditions.24 Based on the results of this previous study, the irradiated rice seeds were grown both in the presence of water and 100 mM NaCl solution. DNA damage and reactive species accumulation were also considered, since they are relevant parameters of the plant response to IR and oxidative stress in general.

Results

Accumulation of DNA damage and enhanced ROS levels in response to γ-rays and salt stress

As DNA damage and ROS production are hallmarks for cell responses to IR, and environmental stresses in general, we investigated the changes in these parameters in rice seedlings and plantlets grown from γ-irradiated seeds, both in the presence of water and NaCl as an osmotic agent.

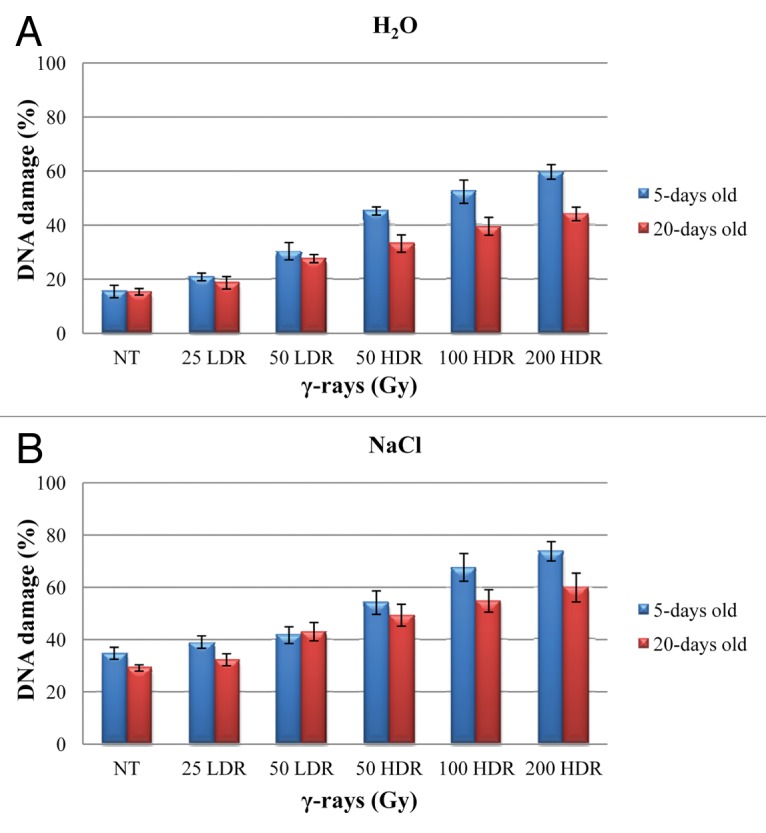

DNA damage was assessed trough SCGE and the results are shown in Figure 1. When seeds were grown in presence of water, the initial DNA damage level in the untreated (NT) samples was around 15% (Fig. 1A). An exponential increase, in a dose-dependent manner was evident in the 5 d old seedlings, peaking at 200 HDR (59.7%). The percentage of DNA damage was significantly increased when the HDR was used, as compared with the LDR treatment. However, after 20 d, a decrease in the percentage of DNA damage was observed, suggesting for the activation of proper DNA repair mechanisms, especially when the HDR treatment was used. When the seeds were imbibed in the presence of 100 mM NaCl solution, the basal levels of DNA damage in the non-irradiated material increased up to 30% (Fig. 1B). In the irradiated samples, the levels of DNA damage were enhanced in a dose-dependent manner in the 5 d old seedlings, with a peak of 74% at 200 HDR. Also in this case, during the 20 d of cultivation, DNA repair processes were activated but at a lesser extent. The DNA damage at 200 HDR was around 60%.

Figure 1. Total DNA damage percentage measured by alkaline comet assay in γ-irradiated 5-d-old seedlings and 20-d-old rice plantlets in the presence of water (A) and 100 mM NaCl solution (B). Results are given as mean values (± SD) of three independent experiments. NT, non-treated control; LDR, low dose rate; HDR, high dose rate.

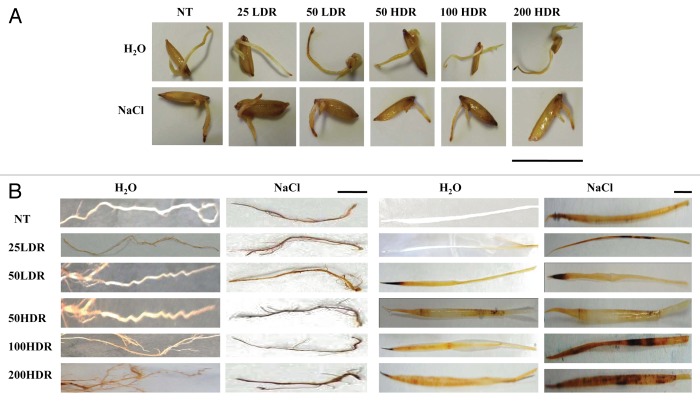

Accumulation of endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was determined by DAB staining, since DAB is oxidized by H2O2 in the presence of haem-containing proteins, such as peroxidases, to generate a dark brown precipitate. The results are shown in Figure 2. In seedlings, H2O2 accumulated also in the non-irradiated material, as this compound is considered an important signaling molecule especially during seed germination.27 H2O2 accumulated mostly in the radical apex but, at this stage, no significant differences were observed between the various treatments (Fig. 2A). However, after 20 d of cultivation, H2O2 accumulation was evident in both roots and leaves (Fig. 2B). This accumulation was more elevated when the HDR treatments were used, especially in the presence of NaCl solution.

Figure 2. Evaluation on hydrogen peroxide production in response to γ-ray treatments in 5-d-old seedlings (A) and 20-d-old rice plantlets (B) as revealed by DAB staining method. Bars represent 1 cm. NT, non-treated control; LDR, low dose rate; HDR, high dose rate.

Increased seed germination potential with no apparent improvement on plant resistance to stress

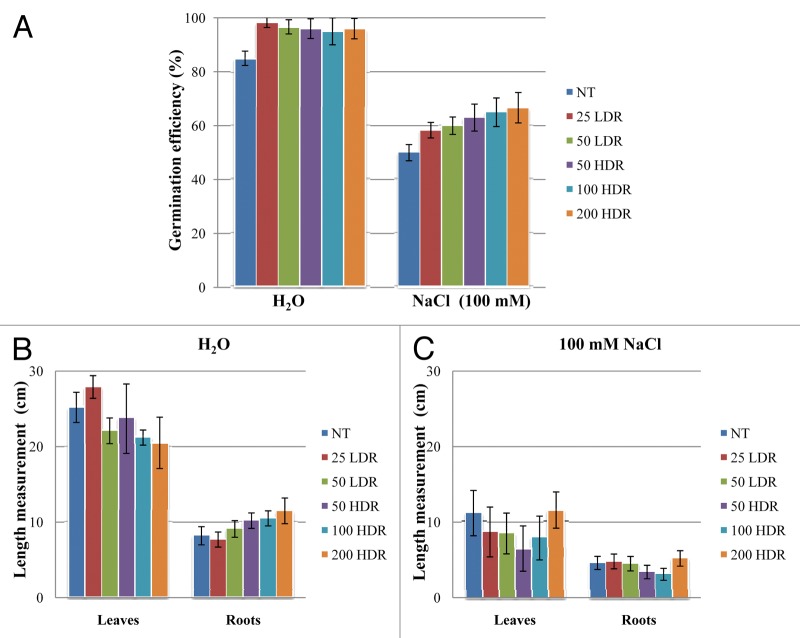

Rice seeds were irradiated with 25 and 50 Gy delivered at a low dose rate (LDR) and 50, 100 and 200 Gy delivered at a high dose rate (HDR) and the germination efficiency was tested under physiological conditions as well as imbibed in a solution containing 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 3A). Seeds with protrusion of the primary root were considered germinated and the germination efficiency in the untreated seeds was 85%. Increased percentage of germination was observed in the irradiated seeds at all tested doses. As expected, when seeds were imbibed in the presence of NaCl solution (100 mM), the germination efficiency was significantly (p < 0.01) lowered (up to 50%). Nevertheless, also in this case, an increase in germination effectiveness was observed when seeds were irradiated (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, when the roots and leaves of 20 d old plantlets were measured, the stimulation effects of the irradiation treatments were no longer apparent (Fig. 3B). No significant differences were observed between the untreated samples and the IR treatments. The high levels of standard deviation may be due to the high variability present in the plant material. In addition, the γ-ray treatments did not apparently caused any increase in the plant resistance to salinity stress (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Percentage of germination in γ-irradiated rice seeds in absence/presence of 100 mM NaCl (A). Measurement of roots and leaves length in 20-d-old rice plantlets grown in greenhouse from γ-irradiated seeds in under physiological conditions (B) and in presence of 100 mM NaCl (C). Values are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent replications with 100 seeds for each replication. NT, non-treated control; LDR, low dose rate; HDR, high dose rate.

MicroRNAs and targeted helicases expression under γ-rays treatment

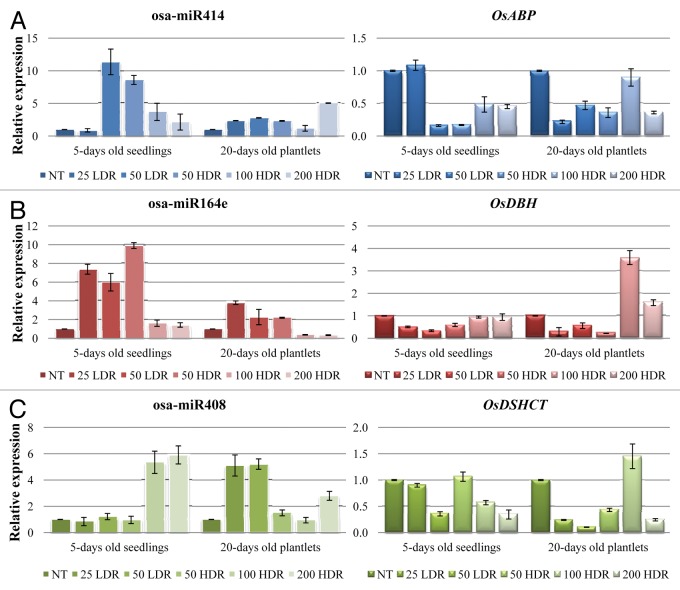

The expression profiles of osa-miR414, osa-miR164e and osa-miR408 along with their targeted helicase genes, OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT, were investigated in 5-d-old seedlings and 20-d-old rice plantlets challenged with different doses of γ-rays (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Expression profiles of osa-miR414 and its target OsABP gene (A), osa-miR164e and its target gene OsDBH (B) and osa-miR408 along with its target gene OsDSHCT (C) in response to γ-ray treatments. For each treatment, data (± SD) were derived from three independent replications. NT, non-treated control; LDR, low dose rate; HDR, high dose rate.

Osa-miR414 presented significant (p < 0.001) upregulation (50 LDR 10.4-fold; 50 HDR 7.6-fold; 100 HDR 2.7-fold; 200 HDR 1.0-fold) in 5-d-old rice seedlings, except the treatment with 25 Gy LDR (Fig. 4A). When the 20-d-old plantlets were analyzed, the upregulation pattern was still maintained (except for 100 HDR treatment) but at lesser levels (25 LDR 1.4-fold; 50 LDR 1.8-fold; 50 HDR 1.3-fold; 200 HDR 4.0-fold). However, in this case the 200 HDR treatment resulted in the highest expression, contrary with the 5 d seedlings where same treatment resulted in the lowest expression. Complementary, the osa-miR414 targeted gene, OsABP, was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated in response to these treatments (Fig. 4A). In the case of 5-d-old seedlings, the gene expression patterns were reduced with 5.2- and 5.9-fold in response to the 50 Gy treatments at both LDR and HDR, respectively. The observed downregulation was less (aprox. 2.0-fold) when 100 and 200 Gy HDR doses were used. As for the 20-d-old plantlets, the lowest transcript level (4.6-fold) was observed with the 25 LDR dose, while in the other treatments the downregulation was around 2.0-fold (except for 100 HDR which showed no significant differences).

Osa-miR164e on the other hand, showed differential levels of expression in seedlings and plantlets (Fig. 4B). In seedlings, it was slightly upregulated in response to 25 LDR (1.4-fold), 50 LDR (1.8-fold) and 50 HDR (1.3-fold), while no significant differences were observed in case of 100 and 200 HDR treatments. In plantlets, the microRNA was upregulated in response to 25 LDR (2.8-fold), 50 LDR (1.3-fold) and 50 HDR (1.2-fold), while it was significantly downregulated when the 100 and 200 HDR (2.6- and 2.9-fold, respectively) were used. As expected, the OsDBH gene expression was negatively correlated with its targeted miRNA (Fig. 4B). In seedlings, downregulation of the gene was observed when the 25 LDR (2.0-fold), 50 LDR (3.0-fold) and 50 HDR (1.7-fold) were used. In plantlets, the significant downregulation was maintained for these treatments, while upregulation was shown in response to 100 HDR (2.6-fold).

As for osa-miR414, its expression pattern was mainly upregulated in response to γ-rays (Fig. 4C). In seedlings, upregulation was observed only in response to the highest doses (100 HDR 4.4-fold; 200 HDR 4.9-fold). Contrary, in case of rice plantlets, significant increase (p < 0.05) in its transcript level was observed in response to the LDR treatments (aprox. 4.0-fold) as well as a slight increase when the 200 HDR (1.8-fold) was used. Also in this case, the microRNA expression pattern was negatively correlated with its targeted helicase OsDSHCT, which was downregulated (Fig. 4C). In seedlings, the OsDSHCT transcript levels were slightly decreased, except for the 25 LDR and 50 HDR treatments. However, this decrease was much more prominent in plantlets, especially with the LDR treatments which showed 4.6- and 9.7-fold decrease, respectively.

Overall, the present results show that the expression patterns of these microRNAs and their targeted genes are nor dose- or time-dependent, but they are however differently expressed in response to both LDR and HDR γ-rays.

γ-rays and salinity stress differentially modulate the microRNAs and targeted genes expression

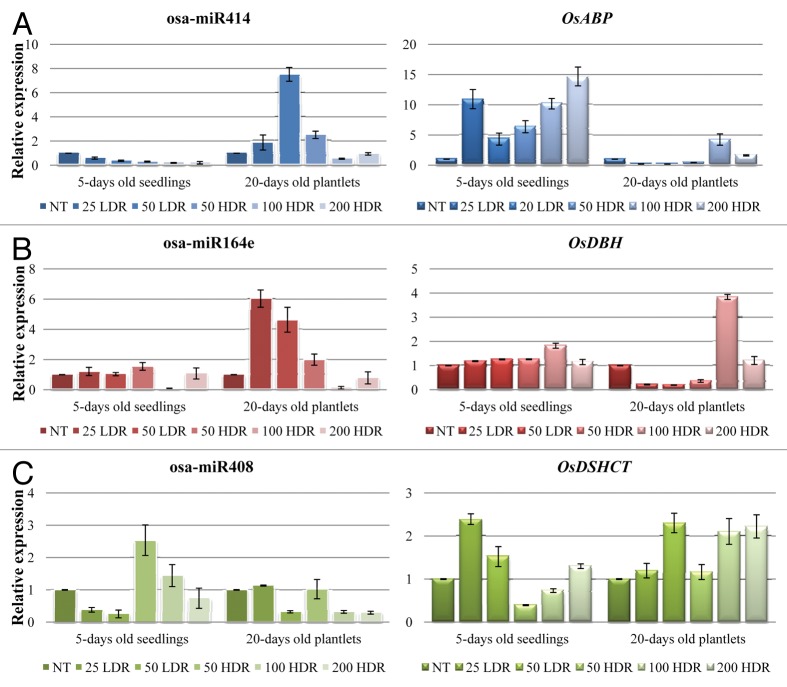

Subsequently, the microRNAs and targeted genes expression patterns were tested in the presence of both γ-rays and 100 mM NaCl solution (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. QRT-PCR results for osa-miR414 and its target OsABP gene (A), osa-miR164e and its target gene OsDBH (B) and osa-miR408 along with its target gene OsDSHCT (C) in response to both γ-irradiation and NaCl-induced stress. For each treatment, data (± SD) were derived from three independent replications. NT, non-treated control; LDR, low dose rate; HDR, high dose rate.

In 5-d-old rice seedlings, the osa-miR414 was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated almost in a dose-dependent manner (25 LDR 1.7-fold; 50 LDR 2.7-fold; 50 HDR 3.3-fold; 100 HDR 5.2-fold; 200 HDR 4.8-fold). However, when its expression was tested in the 20-d-old plantlets, osa-miR414 was upregulated in response to both 50 Gy doses (LDR 6.5- and HDR 1.5-fold, respectively), while it presented a 1.8-fold downregulation when 100 HDR was used (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, its target, the OsABP gene, was upregulated in response to all doses in seedlings (25 LDR 9.9-fold; 50 LDR 3.3-fold; 50 HDR 5.4-fold; 100 HDR 9.1-fold; 200 HDR 13.7-fold). Nonetheless, the observed increase in transcript level was not dose-dependent, since high accumulation was evidenced both with 25 LDR and 200 HDR treatments (Fig. 5A). In plantlets, the OsABP gene was downregulated in response to 25 LDR (4.9-fold), 50 LDR (5.2-fold) and 50 HDR (2.3-fold), while upregulation was observed when the 100 HDR dose (3.3-fold) was used.

Osa-miR164e expression patterns in seedlings showed no significant statistical differences, except for the treatment with 100 HDR which resulted in a 9.7-fold decrease in its transcript levels (Fig. 5B). Alternatively, significant differences (p < 0.001) were observed in rice plantlets. An increase of 5.0-, 3.6- and 1.0-fold was present at 25 LDR, 50 LDR and 50 HDR, while the highest doses (100 and 200 HDR) showed a 7.8- and 1.3-fold decrease in transcript levels. When the expression of OsDBH gene was tested in seedlings, only a slight 0.8-fold increase was observed after treatment with 100 HDR (Fig. 5B). However, in plantlets, this increase was more accentuated (2.8-fold), while downregulation was evident at 25 LDR, 50 LDR and 50 HDR (4.6-, 5.1- and 2.8-fold).

As for osa-miR408 transcript level in seedlings, it showed downregulation when the LDR doses were used (2.6- and 3.9-fold, respectively), while a 1.5-fold upregulation was observed only in response to the 50 HDR treatment (Fig. 5C). In plantlets, a decrease of aprox 3.0-fold was evident at 50 LDR, 100 HDR and 200 HDR. In seedlings, the OsDSHCT gene presented a slight increase (1.4-fold) in its transcript levels when 25 LDR was used and it decreased with the higher doses (50 HDR, 2.5-fold and 100 HDR, 1.4-fold). The gene expression in plantlets showed only a small accumulation of aprox. 1.0-fold at same doses (Fig. 5C).

Generally, the miRNAs expression patterns are different in the presence of both stresses as compared with the results obtained only when γ-rays were used, although also in this case the dose- or time-dependent decrease/accumulation is not evident, except for miR414 in seedlings.

In silico analysis of OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT putative helicases

Little is known on the OsABP (ATP-Binding Protein, LOC_Os06 g33520), OsDBH (DEAD-Box Helicase, LOC_Os04 g40970) and OsDSHCT (DOB1/SK12/helY-like DEAD-box Helicase, LOC_Os11 g07500) genes or their encoded protein sequences. A bioinformatic search revealed that they are DEAD-box helicases, since all three of them possess this specific motif. The DEAD domain contains several ATP-binding sites and it is involved in ATP-dependent RNA or DNA unwinding. However, the helicase activity of these proteins was not yet confirmed. In a recent study, we shown that OsABP gene contains an open reading frame (ORF) of 2,772 nt, encoding a protein of 923 aa, OsDBH possesses an ORF of 2,781 nt that encodes for a protein of 926 aa, while OsDSHCT is characterized by an ORF (3,012 nt) encoding a protein of 1,003 aa.24 The OsABP protein shares around 50% similarity with the DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase 31, while the OsDBH protein revealed 50% similarity with the ATP-dependent DNA helicase Q-like 5-like from other plant species. As for the OsDSHCT protein, a high percent of similarity (~80%) with RNA helicase DOB1/SKI2 proteins was shown.24

In order to better understand their mode of action we performed an in silico analysis for putative protein-protein interactions by using the STRING program. The results of this search are presented in Table 1. The OsABP protein was computationally predicted to interact with proteins involved in tRNA and rRNA processing (tRNA and rRNA cytosine-C5-methylase, pseudouridine synthase), ribosome biogenesis (WD40 repeat nucleolar protein Bop1, Nop58p/Nop5p protein) and other putative helicases. The OsDBH protein interacts mostly with proteins implicated in various DNA repair pathways, like RAD51 and MRE11 which are essential components of the MNR (MRE11/RAD51/NBS1) complex, or MLH1 and MLH3 proteins involved in mismatch repair. DNA topoisomerase III α, endonuclease MUS81 and phosphatidylinositol kinase are associated with DNA topology, stalled replication forks or signal transduction.28-30 OsDSHCT was shown to interact with proteins implicated in RNA degradation and RNA-binding (Rrp6, NIFK), as well as with DNA polymerase σ, playing essential roles in chromatin remodeling and DNA repair31 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in polyubiquitination and post-translational regulation.32

Table 1. List of predicted interacting partners for rice ABP, DBH and DSHCT putative helicases, as revealed by STRING software.

| Protein | Orthologous group | Predicted functional partners |

|---|---|---|

| ABP (KOG0342) | KOG0331 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase |

| KOG1122 | tRNA and rRNA cytosine-C5-methylase (nucleolar protein NOL1/NOP2) | |

| KOG2529 | Pseudouridine synthase | |

| KOG2484 | GTPase | |

| KOG0343 | RNA helicase | |

| KOG0650 | WD40 repeat nucleolar protein Bop1 | |

| KOG0313 | Microtubule binding protein YTM1 | |

| KOG2527 | Ribosome biogenesis protein Nop58p/Nop5p | |

| DBH (KOG0351) | KOG1956 | DNA topoisomerase III α |

| KOG1433 | DNA repair protein RAD51/RHP55 | |

| COG5032 | Phosphatidylinositol kinase | |

| KOG1805 | DNA replication helicase | |

| KOG2310 | DNA repair exonuclease MRE11 | |

| KOG2108 | 3′-5′DNA helicase | |

| KOG2379 | Endonuclease MUS81 | |

| KOG1977 | DNA mismatch repair protein, MLH3 family | |

| KOG1979 | DNA mismatch repair protein, MLH1 family | |

| DSHCT (KOG0948) | KOG1906 | DNA polymerase σ |

| KOG4400 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | |

| KOG2206 | Exosome 3′-5′exoribonuclease complex, subunit PM/SCL-100 (Rrp6) | |

| KOG4208 | Nucleolar RNA-binding protein NIFK | |

| KOG0343 | RNA helicase |

Additionally, the promoter region of the three genes was also investigated by using the PlantCARE database. The cis-elements fond in the promoter sequence, along with their functions are listed in (Table S1). The OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT promoter sequences have as common cis-elements the TATA box, CAAT box and GATA motif, representing core promoter elements, along with light responsive elements (I box, G box, GT1 motif), the W box, involved in stress response and a Skn-1 motif, required for endosperm expression. OsABP promoter also contains cis-acting elements for meristem specific activation (A box, CCGTCC motif), seed specific elements (RY element, AAGAA motif), a sugar responsive sequence (TACT box) and stress responsive elements (ABRE, ACE). The promoter region of OsDBH gene was richer in elements involved in various types of stresses, such as HSE (heat shock element), MBS (MYB binding site involved in drought stress), GARE motif (gibbereline-responsive), F box, ABRE and CGCCG motif. It also contained meristem specific elements (CCGTCC motif, A box), the cis-regulatory element involved in endosperm expression (GCN4 motif), sugar responsive elements (S box, TGG element), the negative-feedback regulator of transcription (AC-1 motif) and an elicitor responsive element (EIRE). As for the OsDSHCT promoter region, it is characterized mainly by the presence of light responsive elements (box 4, AE box, GA motif, MRE, TCCC motif).33

Discussion

Radiological studies indicate that DNA is the principal target for the IR-induced biological effects. IR can also interact with atoms and molecules, particularly with water, to produce free radicals which are further diffused and interact with critical targets causing biological damage.34In the present study we show that ROS, mainly H2O2, did accumulate in response to the induced treatments. In the 5-d-old rice plantlets, H2O2 accumulated also in the non-irradiated material. This could be due to the fact that H2O2 is considered an essential signaling molecule during seed germination and in the early seedling phases.27 Increasing doses of γ-rays induced greater ROS generation also in Arabidopsis thaliana and Petunia hybrida.35,36 Additionally, increased germination potential was evident with all the tested doses, both under physiological and osmotic stress conditions. Despite the stimulatory effect on seed germination, enhanced plant growth or resistance to salt stress were not confirmed in later plant developmental stages. Contrasting reports, describing alleviation of salinity stress upon rice seeds pre-exposure to γ-rays, were published.37

The SCGE analysis revealed accumulation of DNA damage upon exposure to γ-rays. Besides, differences were observed between the LDR and HDR treatments. Only a slight increase in DNA damage levels was evident after LDR treatment, while higher accumulation occurred when the HDR was used. When the 20-d-old plantlets were studied, a decrease in the DNA damage levels was observed as compared with the 5-d-old seedlings. This is an evidence for the activation of DNA repair pathways. However, when the LDR treatment was considered, the repair of the damage was not observed. A recent study performed on P. hybrida cells disclosed dose rate-dependent differences in terms of DNA damage accumulation and repair dynamics, since exposure to LDR failed to activate proper DNA repair mechanisms while HDR strongly enhanced both DNA damage levels and repair processes.36

The present study focused on characterizing the expression patterns of osa-miR414, osa-miR164e and osa-miR408 and their targeted helicase genes in response to both LDR and HDR-induced γ-ray treatments. OsABP (ATP-Binding Protein), OsDBH (DEAD-Box Helicase) and OsDSHCT (DOB1/SK12/helY-like DEAD-box Helicase) predicted helicase targets of osa-miR414, osa-miR164e and osa-miR408 were experimentally validated in a previous study.24 In the same study, it was demonstrated that these helicases were upregulated in response to early-induced salinity stress. Additionally, the OsABP gene was also upregulated under dehydration, abcisic acid (ABA), blue and red light conditions, while it was downregulated when heat and cold treatments were applied to the rice plants.38 However, little is known about these putative proteins which contain all the conserved motifs present in the DEAD-box helicase family, but their specific helicase activities were not yet experimentally validated. In order to get additional information, an in silico study on the possible protein-protein interactions, was performed. The data revealed that these proteins interacted mostly with other proteins involved in RNA metabolism, ribosome biogenesis (OsABP and OsDSHCT) as well as several proteins implicated in different DNA repair pathways (OsDBH and OsDSHCT). In consequence, it can be entailed that they might play some roles in these physiological processes. Furthermore, the presence of various stress-related cis-elements (especially light-responsive elements) in the promoter regions, support for potential roles in plant stress response. The qRT-PCR analysis revealed different patterns of down- and upregulation of the three genes in response to the tested conditions. The most responsive gene was OsDBH, which showed preferential downregulation in 5-d-old seedlings and upregulation in 20-d-old plantlets. These results are in agreement with the activation of the DNA repair mechanisms evidenced in this timeframe. Also the bioinformatic analysis pointed out that this gene might be involved in DNA repair and plant stress adaptation. Several RNA helicases were shown to be involved in the response to harmful environmental conditions like cold, heat, salt, drought, ABA, wounding or UV exposure. It was stated that they could work through ABA-dependent or -independent pathways, or can be subjected to post-translational regulation through phosphorylation cascades.39Their own expression can be regulated with the consequential induction of helicase biochemical activity, thus regulating the expression or activity of downstream mRNA targets.39

The role of miRNAs as important players in the plant stress response has been highlighted in the recent years, though their involvement in specific processes, localized within the nuclear compartment and acting at the level of DNA topology still needs to be clarified. A previous bioinformatic search showed that osa-miR414, osa-miR408 and osa-miR164e possessed multiple predicted targets.23,24 Osa-miR414 was predicted to target six different helicases: the ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX46 and DDX47, the Pre-mRNA-processing ATP-dependent RNA helicase PRP5, the RNA helicase A (RNAhA), an ATP-dependent helicase required to maintain repression (CTD2) and the ATP-binding protein (OsABP). The predicted targets for osa-miR408 were DSHCT, MIP1 (major intrinsic protein 1) and a basic blue copper protein (plastocyanin-like), while osa-miR164e was predicted to target two different mRNAs: DBH and a member of the NAC (no apical meristem) gene family that include the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC1, CUC2 and CUC3) genes, which were already validate as its targets in Arabidopsis.40 The miR408 predicted target corresponding to the plastocyanin-like protein has been previously validated in Arabidposis41 and Medicago truncatula as well.16

Several recent papers described the miRNAs involvement in the response to various stress conditions. For example, miR408 accumulated in response to drought and heavy-metals.40,41 In was also proven that miR164 and miR408 were responsive to cold and drought conditions in Euphorbiaceae plants.42 Ding et al. (2009)43 identified a list of miRNAs in Zea mais that displayed different activities during salt stress. The authors showed that miR164 was downregulated after 24 h of salt shock, and its target NAC1, an early auxin-responsive gene, was upregulated. A similar report provided evidence that miR156, miR166, miR171, miR172, miR319, miR164 along with their target genes, were differentially expressed in stress-tolerant maize hybrids compared with stress-sensitive lines.44

An important aspect that needs to be underlined is that no information on miRNAs expression during γ-ray conditions is currently available in plant system. The results reported in the present study show different expression of the three miRNAs in response to LDR and HDR-induced treatments. Additionally, the expression patterns of their targeted helicase genes were negatively correlated with the miRNAs expression, proving once again the validation of these predictions. No specific dose- or time-dependent expression was observed, however the overall picture potentially shows more induction in response to LDR as compared with HDR. In contrast, this particular field is much better investigated in human cells. In is also essential to emphasize the fact that different responses in terms of radiosensitivity have been highlighted in animals and plants, as reported in a recent study on the Chernobyl disaster, where is showed that the safe dose is within the range of 0.001–1 and 1–100 Gy, respectively.45 Several reports concerning the identification of miRNA targeting proteins involved in DNA repair or their use as biomarkers of radiation exposure in human cells were published in the recent years.13 This is reasonable since, in cancer classification, microRNA profiles correlate more accurately than protein-coding gene transcriptome,46 and in consequence, these molecules are of great importance for human health. In a recent study, the expression profiles of miRNAs isolated from irradiated cells at both LDR and HDR doses were analyzed by microarrays. The study showed that LDR suppressed the progression of malignant cancer cells by controlling the expression of miR-20 and miR-21, while HDR stimulated the expression of miR-197 and the progression of tumorigenesis.47 Niemoeller et al. (2011)48 investigated the IR-induced miRNA expression profiles in six malignant cell lines and they showed that IR caused a two to three fold change in the expression level of miRNAs involved in the regulation of cellular processes such as apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, local immune response and radioresistance. In plants, the only report available regards the computational identification of miRNAs which are putatively expressed under UV-B radiation.22 The authors stated that in A. thaliana, 11 miRNAs, namely miR156, miR157, miR160, miR165, miR167, miR169, miR170, miR172, miR393, miR398 and miR401, were upregulated under UV-B conditions. These miRNAs were predicted to target mainly genes involved in transcription regulation and stress response.

When the miRNAs expression patterns were investigated under both γ-rays and NaCl stress the situation changed. Several reports revealed that treatments with γ-rays may result in enhanced stress tolerance in plants.5-7The qRT-PCR results showed that the miRNAs were mostly downregulated, especially in 5-d-old seedlings. This decrease in mRNAs levels was associated with increase in the transcript levels of their targeted genes. In the 20-d-old plantlets, osa-miR414 and osa-miR164e were downregulated at LDR and upregulated at HDR, while osa-miR408 transcript decreased at both doses. Still, based on these results only, we cannot state if the plants gained tolerance to salinity stress. However, the observed increase in DNA damage and ROS levels when the plants were submitted to both stresses, prove otherwise.

In conclusion, the present study illustrates for the first time in plants different expression profiles of three miRNAs along with their targeted genes in response to LDR and HDR γ-rays. No dose- or time-dependent patterns were evident under the tested conditions, although the existing literature on human cells specifically underlines this type of pattern. This might be explained by the fact that generally, plants are more radioresistant than animals and also possess more redundant genetic information. On the contrary, the increased levels of DNA damage and ROS accumulation were dose-dependent. Therefore, further specific studies are still required in order to better characterize the complex mechanisms activated in plants exposed to IR.

Material and Methods

Plant material and treatments

Rice (Oryza sativa var indica) seeds, belonging to IR64 cultivar, were used in the present study. Dry seeds were exposed to different doses of γ-rays as follows: 25 and 50 Gy delivered at low dose rate (LDR; 0.28 Gy min−1) and 50, 100 and 200 Gy delivered at high dose rate (HDR; 5.15 Gy min−1). The radiation font was supplied by a 60Cobalt source. Subsequently, the seeds were placed on Petri dishes supplied with filter paper for germination, in the presence of both water and a 100 mM NaCl solution. Material was collected at 5 d post-germination and used for further analysis. Another seed lot was sowed in pots containing a mixture of vermiculite, sand and peat moss in 1:1:1 ratio and kept under greenhouse conditions (30/20°C day/night temperature and 12 h photoperiod with 75–80% relative humidity). Also in this case, one lot of plants was watered, while another was grown in the presence of the 100 mM NaCl solution. Plant material was collected after 20 d and used for further analysis.

DNA damage, hydrogen peroxide detection and physiological measurements

The DNA damage was assessed through single cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE), also known as comet assay. Nuclei were extracted from rice seedlings and plantlets as described by Gichner et al. (2000).49 The nuclei were then denatured in alkaline buffer (1 mM Na2EDTA, 300 mM NaOH, pH 13) for 20 min at 4°C and subsequently submitted to electrophoresis in the same buffer for 20 min at 0.72 V cm−1 in a cold chamber. After electrophoresis, slides were washed in 0.4 M TRIS-HCl pH 7.5 three times for 5 min, rinsed in 70% ethanol (v/v) three times for 5 min at 4°C and dried overnight at room temperature. Subsequently, slides were stained with 20 μl DAPI (1 μg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich). For each slide, one hundred nucleoids were scored, using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Z1) with an excitation filter of 340–380 nm and a barrier filter of 400 nm. Nucleoids were classified as described by Collins (2004)50 and the results were expressed as percentage of DNA damage.

The production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was detected using 3′3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as described by Thordal-Christensen et al. (1997).51 Both 5-d-old seedlings and 20-d-old plants were used for the colorimetric assay. Plant material was incubated in 1% DAB solution for 1 h under vacuum and dark conditions. Subsequently, the material was further on incubated overnight under agitation (200 rmp) conditions and still kept in dark. Then the plant material was washed with 75% ethanol for three times in order to remove the chlorophyll. Pictures were taken using a SONY NEX3E5 camera.

For germination experiments, rice seeds were transferred to Petri dishes containing filter papers moistened with 2.5 mL distilled water and 100 mM NaCl solution and kept in a growth room at 30/20°C day/night temperature and 12 h photoperiod and a relative humidity (RH) of 75–80%. Seeds with protrusion of the primary root were considered germinated and counted at three days from the beginning of the experiment. For each treatment combination, 100 seeds were counted. As for the rice plants grown in the greenhouse, the length of roots and leaves were measured after 20 d of cultivation. The measurements were registered for 100 plantlets for each treatment combination.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR for microRNAs expression

For the miRNAs expression levels total RNA was extracted from the plant material by using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) and the cDNA was syntesized by using the NCode™ VILO™ miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) as instructed by the supplier. This kit allows the tailing of microRNAs in a total RNA population, the synthesis of first-strand cDNA from the tailed RNA and the subsequent detection by qRT-PCR.

The EXPRESS SYBR GreenER miRNA qRT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen) was used for qRT-PCR analysis, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To design the miRNA-specific forward primers, the qPCR Primer Design Program provided in the NCode miRNA Database (escience.invitrogen.com/ncode), was used. The Universal qPCR Primer provided in the NCode VILO kit was used as a reverse primer in the qRT-PCR reaction. The small nuclear RNA U6 was used as reference control. The primer sequences are shown in Table S2. The amplification conditions were as follows: UDG incubation step at 50°C for 2 min, initial incubation step at 95°C for 2 min, denaturation step at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing step at 60°C for 1 min, for 40 cycles. The melting temperature analysis (60–95°C) was also performed.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR for gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from plant material by using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. A total quantity of 100 mg plant tissue was used. The RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNaseI (Promega) to eliminate DNA contamination. The RNA quantification was performed using the PicoGene Spectrophotometer (Genetix Biotech). The absorbance ratios of the RNA samples at 260/280 nm and 260/230 nm were between 1.9 and 2.0. The quality of RNA samples was also verified on 1% agarose gel. The cDNA was synthesized by using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

qRT-PCR reactions were performed in a 7,500 Real Time PCR System apparatus (Applied Biosystems). For the OsABP, OsDBH and OsDSHCT gene expression, qRT-PCR primers were design by using the GeneScript Primer Design Program (www.genscript.com/ssl-bin/app/primer) (Table S2). The primer pairs were design to amplify a region containing the cleavage site of osa-miR414, osa-miR168e and osa-miR408, respectively. Predicted fragment size ranged between 150 and 250 bp. The α-Tubulin gene was used as endogenous control. SSoFast EvaGreen Supermix (BioRad) was used for qRT-PCR reaction as indicated by the supplier. The amplification conditions were as follows: enzyme activation 95°C for 30 sec, denaturation step at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing/extension step at 57°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 30 sec, for 40 cycles. Fluorescence data was collected during the extension step and the specificity of qRT-PCR products was confirmed by performing a melting temperature analysis at temperatures ranging from 55°C to 95°C in intervals of 0.5°C. PCR fragments were run in a 2.5% agarose gel to confirm the existence of a unique band with the expected size.

Bioinformatic analysis

The genomic sequences of OsABP (LOC_Os06 g33520), OsDBH (LOC_Os04 g40970) and OsDSHCT (LOC_Os11 g07500) helicases were obtained from the Rice Genome Annotation Project funded by NSF (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/). The miRNAs sequences were obtained from psRNA Target: A Plant Small RNA Regulator Target Analysis Server (plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/). The STRING computer service (string-db.org/) was used to determine the predicted protein-protein interaction. The PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was used to analyze the gene promoter regions and the presence of cis-acting elements.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicates. Results were subjected to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the means were compared by t-Student test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Short-Term Fellowship (Ref. No. F/ROM12-01) Program awarded through the International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB). Work on plant helicases, plant stress signaling and rice transformation in NT’s laboratory is partially supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. Thanks to Prof Armando Buttafava (Department of Chemistry, University of Pavia, Italy) for providing the irradiation source.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/25128

References

- 1.Ahloowalia B, Maluszynski M. Induced mutations – A new paradigm in plant breeding. Euphytica. 2001;118:167–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1004162323428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaka R, Chenal C, Misset MT. Effects of low doses of short-term gamma irradiation on growth and development through two generations of Pisum sativum. Sci Total Environ. 2004;320:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali C, Manzoor A. Radiosensitivity studies in basmati rice. Pak J Bot. 2003;35:197–207. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh N, Balyan H. Induced mutations in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) CV. ”Kharchia 65” for reduced plant height and improve grain quality traits. Adv Biol Res. 2009;3:215–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckey T. Radiation for health. Radio Protection Management. 2003;20:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Chung B, Kim J, Wi S. Effects of in planta gamma-irradiation on growth, photosynthesis and antioxidant capacity of red pepper (Caspicum annuum L.) plants. J Plant Biol. 2005;48:47–56. doi: 10.1007/BF03030564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rakwal R, Agrawal GK, Shibato J, Imanaka T, Fukutani S, Tamogami S, et al. Ultra low-dose radiation: stress responses and impacts using rice as a grass model. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:1215–25. doi: 10.3390/ijms10031215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaiserman AM. Hormesis, adaptive epigenetic reorganization, and implications for human health and longevity. Dose Response. 2010;8:16–21. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.09-014.Vaiserman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Averbeck D. Non-targeted effects as a paradigm breaking evidence. Mutat Res. 2010;687:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonin F, Molina M, Malet C, Ginestet C, Berthier-Vergnes O, Martin MT, et al. GATA3 is a master regulator of the transcriptional response to low-dose ionizing radiation in human keratinocytes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:417. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawlik A, Alibert O, Baulande S, Vaigot P, Tronik-Le Roux D. Transcriptome characterization uncovers the molecular response of hematopoietic cells to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2011;175:66–82. doi: 10.1667/RR2282.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J, Yuan H, Lu C, Liu X, Cao X, Wan M. Jab1 mediates protein degradation of the Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 checkpoint complex. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:514–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joly-TonettiN, LamartineJ. The role of microRNAs in the cellular response to ionizing radiations. In Current Topics in Ionizing Radiation Research, Dr. Mitsuru Nenoi Ed. 2012, ISBN: 978-953-51-0196-3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang T, Xue L, An L. Functional diversity of miRNA in plants. Plant Sci. 2007;172:423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trindade I, Capitão C, Dalmay T, Fevereiro MP, Santos DM. miR398 and miR408 are up-regulated in response to water deficit in Medicago truncatula. Planta. 2010;231:705–16. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capitão C, Paiva JAP, Santos DM, Fevereiro P. In Medicago truncatula, water deficit modulates the transcript accumulation of components of small RNA pathways . BMC Plat Biol. 2011;11:79–93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu H, Gatti RA. MicroRNAs: new players in the DNA damage response. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:151–8. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner-Ecker M, Schwager C, Wirkner U, Abdollahi A, Huber PE. MicroRNA expression after ionizing radiation in human endothelial cells. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:25–35. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girardi C, De Pittà C, Casara S, Sales G, Lanfranchi G, Celotti L, et al. Analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression profiles highlights alterations in ionizing radiation response of human lymphocytes under modeled microgravity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joly-Tonetti N, Viñuelas J, Gandrillon O, Lamartine J. Differential miRNA expression profiles in proliferating or differentiated keratinocytes in response to gamma irradiation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:184–96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Wang G, Zhang W. UV-B responsive microRNA genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:103. doi: 10.1038/msb4100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umate P, Tuteja N. microRNA access to the target helicases from rice. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:1171–5. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.10.12801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macovei A, Tuteja N. microRNAs targeting DEAD-box helicases are involved in salinity stress response in rice (Oryza sativa L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:183–94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuteja N. Plant DNA helicases: the long unwinding road. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:2201–14. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vashisht AA, Tuteja N. Stress responsive DEAD-box helicases: a new pathway to engineer plant stress tolerance. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2006;84:150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barba-Espín G, Hernández JA, Diaz-Vivancos P. Role of H₂O₂ in pea seed germination. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:193–5. doi: 10.4161/psb.18881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao H, Chen XB, McGowan CH. Mus81 endonuclease localizes to nucleoli and to regions of DNA damage in human S-phase cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4826–34. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krasilnikov MA. Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase dependent pathways: the role in control of cell growth, survival, and malignant transformation. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;65:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litvak S, Castroviejo M. Plant DNA polymerases. Plant Mol Biol. 1985;4:311–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02418250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzucotelli E, Belloni S, Marone D, De Leonardis AM, Guerra D, Di Fonzo N, et al. The e3 ubiquitin ligase gene family in plants: regulation by degradation. Curr Genomics. 2006;7:509–22. doi: 10.2174/138920206779315728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.HanW, YuKN. Response of cells to ionizing radiation. In Advances in Biomedical Sciences and Engineering, Bentham Science Publisher Ltd 2009: 204-262. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim DS, Kim JB, Goh EJ, Kim WJ, Kim SH, Seo YW, et al. Antioxidant response of Arabidopsis plants to gamma irradiation: Genome-wide expression profiling of the ROS scavenging and signal transduction pathways. J Plant Physiol. 2011;168:1960–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donà M, Ventura L, Macovei A, Confalonieri M, Savio M, Giovannini A, et al. Gamma irradiation with different dose rates induces different DNA damage responses in Petunia x hybrida cells. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:780–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song JY, Kim DS, Lee MC, Lee KJ, Kim JB, Kim SH, et al. Physiological characterization of gamma-ray induced salt tolerant rice mutants. AJCS. 2012;6:421–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macovei A, Vaid N, Tula S, Tuteja N. A new DEAD-box helicase ATP-binding protein (OsABP) from rice is responsive to abiotic stress. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:1–6. doi: 10.4161/psb.21343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owttrim GW. RNA helicases and abiotic stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3220–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhoades MW, Reinhart BJ, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel B, Bartel DP. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell. 2002;110:513–20. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol Cell. 2004;14:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng C, Wang W, Zheng Y, Chen X, Bo W, Song S, et al. Conservation and divergence of microRNAs and their functions in Euphorbiaceous plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:981–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding D, Zhang L, Wang H, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Zheng Y. Differential expression of miRNAs in response to salt stress in maize roots. Ann Bot. 2008;103:29–38. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong YM, Elling AA, Chen B, Deng XW. Differential expression of microRNAs in maize inbread and hybrid lines during salt and drought stress. Am J Plant Sci. 2010;1:69–76. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2010.12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geras’kin SA, Fesenko SV, Alexakhin RM. Effects of non-human species irradiation after the Chernobyl NPP accident. Environ Int. 2008;34:880–97. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cha HJ, Seong KM, Bae S, Jung JH, Kim CS, Yang KH, et al. Identification of specific microRNAs responding to low and high dose γ-irradiation in the human lymphoblast line IM9. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:863–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niemoeller OM, Niyazi M, Corradini S, Zehentmayr F, Li M, Lauber K, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles in human cancer cells after ionizing radiation. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gichner T, Ptácek O, Stavreva DA, Wagner ED, Plewa MJ. A comparison of DNA repair using the comet assay in tobacco seedlings after exposure to alkylating agents or ionizing radiation. Mutat Res. 2000;470:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(00)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collins AR. The comet assay for DNA damage and repair: principles, applications, and limitations. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;26:249–61. doi: 10.1385/MB:26:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang Z, Wei Y, Collinge DB. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants.H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 1997;11:1187–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061187.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.