Abstract

Objectives

Given reported age and sex disparities in access to kidney transplantation (KT), we sought to explore whether these disparities originate at the time of pre-referral discussions about KT.

Design

Cross-sectional survey

Setting

26 outpatient dialysis centers in Maryland

Participants

416 patients who had recently initiated hemodialysis treatment

Measurements

Participants reported whether medical professionals (nephrologist, primary medical doctor, dialysis staff) and social group members (significant other, family member, friend) discussed KT with them and, when applicable, rated the tone of discussions. Relative risks were estimated using modified Poisson regression.

Results

Participants aged ≥65 years were much less likely to have had discussions with medical professionals (44.5% vs. 74.8%, p<0.001) or social group members (47.3% vs. 63.1%, p=0.005). Irrespective of sex, and independent of race, health-related factors, and dialysis-related characteristics, older adults were less likely to have had discussions with medical professionals (1.13-fold, 95% CI:1.03-1.24, less likely for each 5-year increase in age through 65 and 1.28-fold, 95% CI: 1.14-1.42, for each 5-year increase in age beyond 65). Irrespective of age, females were 1.45-fold (95% CI: 1.12-1.89) less likely to have had discussions with medical professionals. Males were 1.04-fold (95% CI: 0.99-1.10) less likely and females 1.17-fold less likely (95% CI: 1.10-1.24), for each 5-year increase in age, to have discussions with social group members. Among those who actually had discussions with medical professionals or social group members, older participants described these discussions as less encouraging (p<0.01).

Conclusion

Older adults and females undergoing hemodialysis are less likely to have discussions about KT as a treatment option, supporting a need for better clinical guidelines and education for these patients, their social network, and their providers.

Keywords: dialysis, kidney transplantation, access to transplantation, age disparities, sex disparities

Introduction

The majority of patients initiating dialysis are over 65 years of age.1 The preferred form of renal replacement for appropriate candidates with end stage renal disease (ESRD) is kidney transplantation (KT).2 Older patients show improved survival and quality of life following KT compared to those who remain on dialysis,3-6 yet age disparities in access are well documented, especially among older women.7-9 This age disparity may be medically justified in part, as some age-related comorbid conditions make older patients less appropriate transplant candidates. However, in a study of potentially excellent older candidates (in the top quintile of older recipients, with 3-year post-KT survival exceeding 87.6%), only 23.7% were listed for transplantation, and of potentially good older candidates (with 3-year post-KT survival exceeding 78.3%), only 8.7% had access to this potentially life-extending treatment modality.10

To achieve access to transplantation, a patient must first have the opportunity to discuss KT with a provider and be referred for evaluation. With few guidelines specific to older adults, providers often use chronologic age in deciding whether to discuss KT with a patient,11 presumably because this may represent a surrogate for risks to successful transplantation such as comorbidities, geriatric syndromes, decreased social support, and shorter life expectancy. Nevertheless, because of the heterogeneity of health status among older adults,12 chronologic age alone is a poor predictor of who would benefit from KT.10 Based on the evidence for improved survival and quality of life for patients of all ages with ESRD, the American Society of Transplantation evaluation guidelines state, “there should be no absolute upper age limit for excluding patients whose overall health and life situation suggest that transplantation would be beneficial.”13 Dialysis providers, therefore, need to make potentially appropriate patients of all ages aware of KT as a treatment option,14 particularly given that patient treatment preferences are based on prognostic expectations.15 We hypothesized that failure of the dialysis provider to discuss KT with older adults exacerbates the age disparity in KT access.

In addition to discussion about KT with a medical provider, discussions with family and friends often factor into the decision to pursue KT. Although few studies have assessed the role of social support in access to KT, social support networks may help patients through the pre-transplant evaluation period.16, 17 For example, patients with high levels of instrumental support are more likely to complete pre-transplant evaluations including pre-operative risk stratification and testing18 and to achieve a live donor KT.19 We, therefore, hypothesized that failure of social group members to discuss KT with older adults also exacerbates the age disparity in KT access.

Because access to transplantation involves a shared decision-making process between the patient, providers, and social support network, we sought to understand discussions about KT from the patient-perspective. Specifically, the aims of this study were to determine whether older patients undergoing hemodialysis were less likely than their younger counterparts to have discussions about KT as a treatment option, to compare the tone of discussions by age, and to assess whether associations between age and KT discussion differ by sex.

Methods

Study Population

This study was a cross-sectional, in-person survey of 416 patients who had initiated hemodialysis within the prior 6 months at 26 free-standing dialysis centers in Baltimore city and 6 surrounding counties in Maryland. Eligibility criteria included: age ≥18 years and English-speaking. Exclusion criteria included: living in a hospice, nursing facility, or prison; having a pacemaker; pregnant or breastfeeding; cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer within the prior 5 years; dementia, Alzheimer's, or schizophrenia; and HIV/AIDS. All study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Characteristics

Demographics (age, sex, race, employment, household size, and income); health behavior (smoking and alcohol use); dialysis-related characteristics (time on dialysis and time between the first nephrologist visit and dialysis initiation); and medical history including asthma/COPD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis C or B (HCV/HBV), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (coronary artery disease/angina/myocardial infarction/heart failure) were obtained by participant self-report. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported height and weight.

Primary Outcome: Discussion about KT

Participants were asked, “Have any of the following people discussed kidney transplantation with you?”: nephrologist, primary medical doctor (PMD), dialysis staff, significant other, family member, and friend. If the participant reported discussion with at least one individual in a given category, the participant was also asked to rate discussions with individuals in this category as encouraging, neutral, or discouraging. Discussions about KT were analyzed by discussant category and by grouped discussant categories which included medical professionals (i.e. whether the patient reported a discussion with either nephrologist, PMD, or dialysis staff) or social group members (significant other, family member, or friend).

Statistical Analysis

Associations between participant characteristics and whether discussions occurred with each of the 2 groups of discussants (medical professionals or social group members) were explored using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, Hodges-Lehmann's test for equal medians for non-normally distributed continuous variables, or t-tests for pseudonormally distributed continuous variables. Relative risks (RR) of discussion were estimated using modified Poisson regression as previously described.20, 21 Two models were fit to ensure that inferences were not sensitive to covariate selection: one based on statistical significance or a priori biological rationale and one empirically reflecting optimal parsimony by minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The best functional form of age was determined empirically to be continuous for both models (reported for ease of interpretation as “for each 5-year increase in age”) with a linear spline at age 65 years in the final model for discussion with medical professionals. Interactions between age and other patient characteristics, as well as between age and discussant group, were also explored. Differences in rated tone of discussions were quantified using ordered logistic regression, with an order of no discussion, discouraging discussion, neutral discussion, and encouraging discussion. All analyses were performed using STATA 12.1/SE (College Station, Texas).

Sensitivity Analyses

In addition to the total number of comorbidities, specific aspects of each individual comorbidity may impact whether KT is discussed. Therefore, sensitivity analyses adjusting for all comorbidities individually within the same model were performed. Because certain CVD-related conditions and HCV/HBV infection are considered relative contraindications for transplantation, patients with these conditions may be less likely to discuss KT for medically-appropriate reasons. As such, analyses excluding those with CVD or HCV/HBV also were performed. Finally, because HIV/AIDS is not an absolute contraindication for KT, we performed analyses that included participants with a history of HIV/AIDS (as sensitivity analyses to the primary analyses that excluded those with HIV/AIDS). No changes in inference were appreciated in any of these sensitivity analyses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 416 participants, average age was 56.2 years, 26.4% were older (aged ≥65 years), 46.2% were female, 66.4% were African American, 12.8% had already been evaluated by a transplant center at the time of study enrollment, and the median time on dialysis was 2.1 months. Older participants (aged ≥65 years) were less likely to be working (9.2% vs. 19.6%, p=0.011), more likely to have smaller household (median of 2 vs. 3, p=0.001), and more likely to married or widowed (married 42.7 vs. 30.8 and widowed 35.5 vs. 5.6 , p<0.001). Older and younger (aged <65 years) participants differed very little in health-related characteristics, except that older participants were more likely to have CVD (46.7% vs. 34.6%, p=0.028) while younger participants were more likely to have HCV/HBV (18.5% vs. 4.6%, p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants initiating hemodialysis, by age.

| Age <65 yrs (n=306) | Age ≥65 yrs (n=110) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean [SD] | 50.1 [10.2] | 73.2 [5.8] | |

| Female sex | 45.8 | 47.3 | 0.82 |

| African American raceb | 72.6 | 49.1 | <0.001 |

| Currently working | 19.6 | 9.2 | 0.011 |

| Combined family income | |||

| <$50,000 | 57.4 | 56.3 | 0.97 |

| $50,000 - $100,000 | 16.3 | 15.5 | |

| >$100,000 | 6.2 | 6.8 | |

| refused | 20.1 | 21.4 | |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Grade school or less | 34.5 | 37.3 | 0.84 |

| High school | 21.4 | 19.1 | |

| Post-secondary education | 44.1 | 43.6 | |

| Household size, median [IQR] | 3 [2,4] | 2 [1,3] | 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 30.8 | 42.7 | <0.001 |

| Single | 33.8 | 2.7 | |

| Separated/divorced | 29.8 | 19.1 | |

| Widowed | 5.6 | 35.5 | |

| Current alcohol use | 18.9 | 12.1 | 0.23 |

| Smoking cigarettes, ever | 23.2 | 16.4 | 0.10 |

| BMI, median [IQR] | 28.5 [24.4, 35.5] | 27.7 [23.8, 31.7] | 0.37 |

| No. comorbiditiesc, mean [SD] | 2.2 [1.0] | 2.2 [0.9] | 0.82 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 55.3 | 56.5 | 0.91 |

| Hypertension | 97.1 | 95.3 | 0.37 |

| CVD | 34.6 | 46.7 | 0.028 |

| Asthma/COPD | 19.6 | 22.2 | 0.58 |

| HCV/HBV | 18.5 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Months between first seeing nephrologist and dialysis initiation | |||

| 0 | 23.7 | 19.3 | 0.25 |

| <3 | 13.2 | 11.0 | |

| 3 – 12 | 16.8 | 11.9 | |

| ≥12 | 46.4 | 57.8 | |

| Time on dialysis (months), median [IQR] | 2.0 [1.4, 2.9] | 2.3 [1.4, 3.3] | 0.10 |

All cells represent percentages unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation, IQR = interquartile range, BMI = body mass index, CVD = cardiovascular disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HCV = hepatitis C viral infection, HBV = hepatitis B viral infection

P-values comparing those aged ≥65 years to those aged <65 years determined using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and t-tests of equal means for continuous variables (psuedonormal distribution) or a Hodges-Lehmann non-parametric k-sample test on equality of medians for continuous variables (non-normal distribution).

African American race compared to Caucasian/other race which was comprised of 92.1% Caucasian, 2.1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 2.9% Asian/Asian American, and 2.9% Other.

Comorbidities include diabetes; hypertension; CVD (coronary artery disease/angina/myocardial infarction/heart failure); asthma/COPD; HCV/HBV

Discussion about KT with Medical Professionals

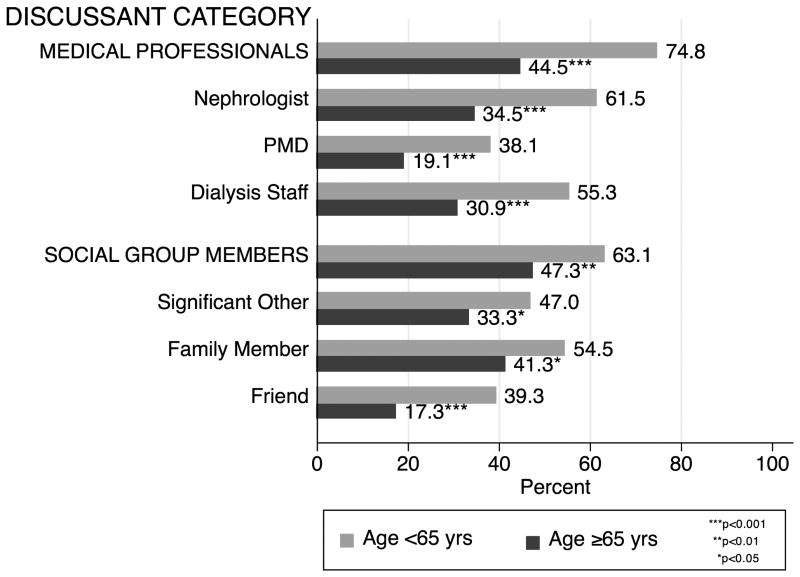

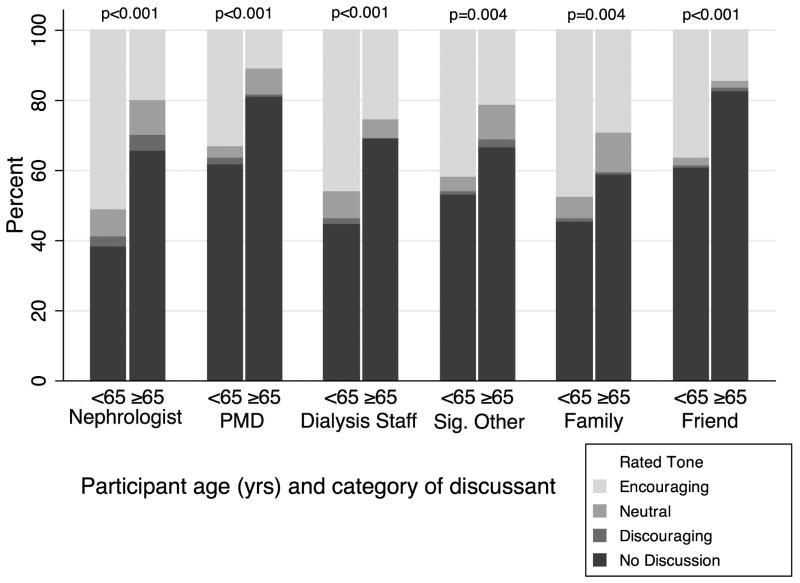

Older participants were much less likely to have had discussions about KT with medical professionals (44.5% vs. 74.8%, p<0.001), specifically with a nephrologist (34.5% vs. 61.5%, p<0.001), a PMD (19.1% vs. 38.1% p<0.001), and dialysis staff (30.9% vs. 55.3%, p<0.001) (Figure 1). On a scale of encouragement (ranging from no discussion to discouraging, neutral, and encouraging discussions), older participants reported lower encouragement from all categories of medical professionals compared to younger participants (p<0.001) (Figure 2), with no differences by sex. Older age was independently associated with less discussion about KT: after adjusting for race, number of comorbidities, BMI, ever smoking, household size, time on dialysis, and time of first nephrologist visit prior to dialysis initiation, each 5-year increase in age through age 65 was associated with 1.13-fold (95% CI: 1.03-1.24, p=0.011) lower likelihood and each 5-year increase in age beyond age 65 was associated with an additional 1.28-fold (95% CI: 1.14-1.42, p<0.001) lower likelihood of having had discussions with medical professionals (Table 2). In other words, for example, a person aged 75 years was 2.09-fold less likely (i.e. half as likely) to have had discussions about KT with medical professionals compared to a person aged 55 years (RR = 2.09 = 1.132 * 1.282). Female sex was also independently associated with lower likelihood of having had discussions with medical professionals (adjusted RR 1.45, 95% CI: 1.12-1.89, p=0.005) whereas African American race was not (adjusted RR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.66-1.16, p=0.35). Estimates were consistent in fully adjusted and parsimonious models (Table 2).

Figure 1. Percent of participants who discussed kidney transplantation with different categories of discussants.

Bars show the percent of participants who had discussed kidney transplantation with different categories of discussants. Medical Professionals include any or all of the following: nephrologist(s), PMD(s), dialysis staff. Social Group Members include any or all of the following: significant other(s), family member(s), friend(s). The percentage of those in the aged ≥65 yrs category who had discussed KT was significantly lower (Fisher's exact test p<0.05) for all 6 categories of potential discussants.

Abbreviations: PMD = primary medical doctor

Figure 2. Discussion occurrence and tone, by discussant category and participant age.

Stacked bars illustrate whether discussion about kidney transplantation occurred and the rated tone (encouraging, neutral, discouraging) among those discussions that did occur with categories of medical professionals (nephrologist, PMD, dialysis staff) and categories of social group members (significant other, family member, friend). P-values were calculated using ordered logistic regression.

Abbreviations: PMD = primary medical doctor, Sig. Other = significant other

Table 2. Associations between age and discussions about kidney transplantation with medical professionals or social group members.

| Unadjusted | Full modela | Parsimonious modelb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Professionalsc | |||

| RR per 5 yrs of age (95% CI)d | |||

| Ages 18 to <65 yrs | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) | 1.11 (1.02-1.21) |

| Ages ≥65 yrs | 1.25 (1.15-1.37) | 1.28 (1.14-1.42) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) |

| RR for females compared to males | 1.34 (1.02-1.77) | 1.45 (1.12-1.89) | 1.36 (1.05-1.76) |

|

| |||

| Unadjusted | Full modela | Parsimonious modelb | |

|

| |||

| Social Group Memberse | |||

| RR per 5 yrs of age (95% CI)f | |||

| All ages among all participants | 1.08 (1.04-1.13) | 1.09 (1.05-1.14) | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) |

| All ages among males | 1.06 (0.84-1.34) | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) |

| All ages among females | 1.16 (1.09-1.23) | 1.17 (1.10-1.24) | 1.16 (1.09-1.23) |

Abbreviations: RR = Relative Risk, CI = Confidence Interval

Adjusted for age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, body mass index, ever smoking, household size, time on dialysis, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation.

Parsimonious model derived using AIC from the Full model.

Lack of discussion with medical professional adjusted for sex and ever smoking.

Lack of discussion with social group member outcome adjusted for ever smoking.

Medical Professionals include any or all of the following: nephrologist, primary medical doctor, dialysis staff.

Relative Risks and 95% CI's were modeled using modified Poisson Regression. Age was modeled as a continuous variable using a linear spline term with a knot at age 65, and the risk was modeled per 5-year increase in age.

Social Group Members include any or all of the following: significant other, family member, friend.

Relative Risks and 95% CI's were estimated using modified Poisson regression. Age was modeled as a continuous variable per 5-year increase in age.

The relative risk for discussion about kidney transplantation (KT) with medical professionals in the full model is interpreted as: for each 5-year increase in age, after adjusting for sex, race, number of comorbidities, body mass index, ever smoking, household size, time on dialysis, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation, those aged <65 years were 1.13 fold less likely (95% CI: 1.03-1.24) and those aged ≥65 years were 1.28-fold less likely (95% CI: 1.14-1.42) to have had a discussion about KT. In other words, for example, a person aged 75 years was 2.09-fold less likely to have had a discussion about KT with a medical professional compared to a person aged 55 years (RR = 2.09 = 1.132 * 1.282). The relative risk for discussion about KT with social group members in the full model is interpreted as: for each 5-year increase in age, after adjusting for race, number of comorbidities, body mass index, ever smoking, household size, time on dialysis, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation, females were 1.17-fold less likely (95% CI: 1.10-1.24) and males were 1.04-fold less likely (95% CI: 0.99-1.10) to have had a discussion about KT with a social group member.

Discussion about KT with Social Group Members

Older participants were also much less likely to have had discussions about KT with social group members (47.3% vs. 63.1%, p=0.005), specifically with a significant other (33.3% vs. 47.0%, p=0.024), a family member (41.3% vs. 44.5%, p=0.019), and a friend (17.3% vs. 39.3%, p<0.001) (Figure 1). On a scale of encouragement (ranging from no discussion to discouraging, neutral, and encouraging discussions), older participants reported lower encouragement from all categories of social group members compared to younger participants (p<0.005) (Figure 2), with no difference by sex. As with medical professionals, older age was independently associated with less discussion about KT: after adjusting for race, number of comorbidities, BMI, ever smoking, household size, time on dialysis, and time of first nephrologist visit prior to dialysis initiation, each 5-year increase in age was associated with 1.09-fold (95% CI: 1.05-1.14, p<0.001) lower likelihood of having had a discussion with social group members (Table 2). Female sex was not independently associated with lower likelihood of having had discussions with social group members per se (adjusted RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.81-1.26, p=0.91) but did have a strong interaction with the effect of age (see below). African American race was not associated with having had discussions (adjusted RR=1.03, 95% CI: 0.81-1.30, p=0.821). Estimates were consistent in fully adjusted and parsimonious models (Table 2).

Modification of the Association between Discussion and Age by Sex

The independent association between age and discussion with medical professionals did not differ by sex (p-values for the interactions between sex and age splines were 0.74 and 0.38). However, the independent association between age and discussion with social group members did differ by sex (p-value for the interaction between age and sex was 0.005): among males, older age was not associated with lower likelihood of having had discussions about KT, while among females, each 5-year increase in age was associated with 1.17-fold (95% CI: 1.10-1.24, p<0.001) lower likelihood of having had discussions about KT with social group members (Table 2).

Modification of the Association between Discussion and Age by Race

The association between age and discussion with medical professionals did not differ by race (p-values for the interactions between race and age splines were 0.77 and 0.51, respectively). Similarly, the association between age and discussion with social group members did not differ by race (p-value for the interaction between age and race was 0.24).

Modification of the Association between Discussion and Age by Comorbidities

The association between age and discussion with medical professionals differed by number of comorbidities (p=0.024 for the interaction between number of comorbidities and age through age 65), with a threshold at 65 (p=0.39 for the interaction between number of comorbidities and age beyond age 65). In other words, an increasing number of comorbidities decreased the impact of increasing age on lack of discussion, but only through age 65. For example, a person aged 55 years with one comorbidity was 1.53-fold (95% CI: 1.19-1.97, p=0.001) less likely to discuss KT with a medical professional compared to a person aged 45 years with one comorbidity; whereas a person aged 55 years with two comorbidities was 1.30-fold (95% CI: 1.08-1.57, p=0.005) less likely to discuss KT compared to a person aged 45 years with two comorbidities. In contrast, the association between age and discussion with social group members did not differ by number of comorbidities (p-value for the interaction between age and number of comorbidities was 0.36).

Modification of the Association between Discussion and Age by Discussant Category

The association between age and discussion differed by discussant group but only among older participants (p-value for the interaction between discussant group and age was 0.001). In other words, the age-wise decrease in likelihood of discussion about KT with older participants was more pronounced for medical professionals than for social group members, but this effect modification was not observed among younger participants (p-value for the interaction 0.25) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Predicted probability of discussion about kidney transplantation with medical professionals or social group members, by participant age.

Plot lines show the predicted probability of having had discussion about kidney transplantation (KT) with a medical professional or a social group member, based on a linear regression with a spline (knot at 65 years). The lines show that the spline term is unnecessary for discussion with social group members, but is needed for discussion with medical professionals. The lines also illustrate effect modification of the association between being less likely to have had discussions about KT and age by the discussant group (medical professional vs. social group member) for participants aged ≥65 years (p-value for the interaction term =0.010). While the age-wise decrease in predicted probability of discussion about KT with medical professionals and social group members occurred for participants of all ages, the age-wise decrease in predicted probability of discussion about KT was more pronounced with medical professionals than with social group members for participants aged ≥65. No effect modification of the association between discussion and older age by discussant group was observed for those aged <65 years (p-value for the interaction 0.55

Discussion

In this multi-center cross-sectional study of 416 patients who had recently initiated hemodialysis treatment, older and female participants were much less likely to report that medical professionals or social group members had discussions with them about KT. After accounting for race, health-related factors, time on dialysis, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation, older adults were less likely to have had discussions with medical professionals (1.13-fold less likely for each 5-year increase in age through age 65 and 1.28-fold additionally less likely for each 5-year increase in age beyond age 65). Irrespective of age, females were 1.45-fold less likely to have had discussions with medical professionals. Females were also 1.17-fold less likely for each 5-year increase in age to have had discussions about KT with social group members, whereas age had little impact on discussions with social group members among males. Among those who had discussions with medical professionals or social group members, older participants described these discussions as less encouraging than younger participants.

The age disparity in access to KT may be caused by older patients declining information about KT, not pursuing evaluation after provision of information, or not meeting evaluation criteria. However, a discussion about KT is required before information is provided, referral to a transplant center is made, and evaluation for transplant eligibility occurs. Our findings suggest that the timeline of disparity may occur even earlier in the process, at the time of initial discussion about treatment modalities for ESRD. The paucity of discussions with medical professionals is particularly concerning given that proper informed consent for hemodialysis initiation requires discussion of alternative treatments as well as expectations for how a patient would fair with each treatment option. As such, we would expect all patients to report discussion with medical professionals and perhaps only differ in the perceived tone, yet this was far from the case.

While lack of patient comprehension or retention may contribute to whether patients report discussing KT,22 our findings suggest that decisions about who should be informed about KT are likely provider-driven and driven strongly by age. Previous evidence that nephrologists are less likely to educate older patients about KT specifically due to patient age7 supports our results. Moreover, our findings are consistent with, and possibly mediated by, the lack of clinical transplant candidacy guidelines and tools specific to older patients with age-associated multimorbidity.23

Females of all ages were less likely to have discussions about KT with medical professionals compared to males. While disparity in access to KT among females24-27 and in particular among older females8 has been documented, our findings that older females were less likely to have discussions about KT with social group members introduces a novel potential mechanism for this sex disparity. That is, reduced access to KT among older females within the clinical setting may be further exacerbated by lack of social support. One possible explanation is that older female patients, their family, and their friends may perceive that females cannot withstand a surgical procedure as well as males. Alternatively, females may be the primary care-takers in their family and not consider KT because they feel that they lack appropriate support for post-operative care.

This study has several limitations. First, African Americans were over-represented in our study population compared to those initiating dialysis in the US (67% vs. 28%1). However, this difference would only bias our inferences if race modified the relationship between age and our outcomes. Since no interactions with race were identified, we feel confident that the over-representation of African Americans was unlikely to have affected our inferences; in fact, this over-representation might actually be advantageous in terms of statistical power to have detected such interactions. Second, although we drew participants from six counties comprising 51% of the adult incident hemodialysis population in Maryland, the dialysis centers were located in more densely populated areas; generalizability to dialysis populations in rural settings would be limited in the unlikely case of an interaction between urban/rural location and our research findings. Third, because participants had not been specifically evaluated for KT, we could not be sure that all participants were appropriate candidates. Nevertheless, we excluded participants with contraindicated conditions as measured in our study, so eligibility was likely. Finally self-reported medical history may be subject to reporting bias. However, misclassification of medical history is likely non-differential across all ages and would not be expected to substantially affect relative risk estimates.

In conclusion, older adults are less likely to have discussions about KT as a treatment option. Older age was independently associated with lower likelihood of discussion with medical professionals among both males and females, while older age was independently associated with lower likelihood of discussion with social group members only among females. Irrespective of age, female sex was also independently associated with lower likelihood of discussion with medical professionals. Further investigation into the reasons for sex disparity in access to KT focusing on mechanisms within and outside of the clinic are needed. Perhaps more immediately, however, clinical guidelines for identifying older patients likely to benefit from KT and recommended approaches for discussing KT with older patients are needed to reduce the substantial age disparity in access to KT.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the study participants and the staff at the participating dialysis clinics. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AG042504 (Segev, PI), R01DK072367 (Parekh, PI), and R21AG034523 (Segev, PI). Megan Salter was supported by T32AG000247 from the National Institute on Aging. Mara McAdams-DeMarco was supported by the Carl W. Gottschalk Research Award from the American Society of Nephrology and the Johns Hopkins Pepper Center (2P30AG021334-11).

Sponsor's Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of this paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper

Author Contributions: Salter, Segev: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article, and revising it critically for important intellectual content. McAdams-DeMarco, Law, Kamil: analysis and interpretation of the data and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Meoni, Jaar, Sozio, Kao, Parekh: acquisition of the data, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors: final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Reports: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincenti F. A decade of progress in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:S52–61. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000126928.15055.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang FP, Novick AC, Sun GH, et al. Graft outcomes of living donor renal transplantations in elderly recipients. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2299–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill JS, Schaeffner E, Chadban S, et al. Quantification of the early risk of death in elderly kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2012;13:427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, et al. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: Results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83:1069–1074. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259621.56861.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, et al. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Oberai PC, et al. Age and comorbidities are effect modifiers of gender disparities in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:621–628. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vamos EP, Novak M, Mucsi I. Non-medical factors influencing access to renal transplantation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grams ME, Kucirka LM, Hanrahan CF, et al. Candidacy for kidney transplantation of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, et al. Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA. 2011;306:620–626. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science. 1987;237:143–149. doi: 10.1126/science.3299702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasiske BL, Cangro CB, Hariharan S, et al. The evaluation of renal transplantation candidates: Clinical practice guidelines. Am J Transplant. 2001;1(Suppl 2):3–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Summary of Recommendation Statements. Kidney Int Supplements. 2013;3:5–14. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1206–1214. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, et al. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:734–745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur T. The role of social networks: a novel hypothesis to explain the phenomenon of racial disparity in kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:678–681. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.35672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark CR, Hicks LS, Keogh JH, et al. Promoting access to renal transplantation: the role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1187–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0628-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garonzik-Wang JM, Berger JC, Ros RL, et al. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93:1147–1150. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens T, Taeger D, Wellmann J, et al. Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies. A comparison between prevalence odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy DM, Waite KR, Curtis LM, et al. What did the doctor say? Health literacy and recall of medical instructions. Med Care. 2012;50:277–282. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318241e8e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg PP, Furth SL, Fivush BA, et al. Impact of gender on access to the renal transplant waiting list for pediatric and adult patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:958–964. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jindal RM, Ryan JJ, Sajjad I, et al. Kidney transplantation and gender disparity. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:474–483. doi: 10.1159/000087920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaubel DE, Stewart DE, Morrison HI, et al. Sex inequality in kidney transplantation rates. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2349–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biller-Andorno N. Gender imbalance in living organ donation. Med Health Care Philos. 2002;5:199–204. doi: 10.1023/a:1016053024671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]