Abstract

Purpose

Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have proven utility as contrast agents in many MRI applications. Previous quantitative IONP mapping has been performed using mainly T2* mapping methods. However, in applications requiring high IONP concentrations, such as magnetic nanoparticles based thermal therapies, conventional pulse sequences are unable to map T2* because the signal decays too rapidly. In this article, sweep imaging with Fourier transformation (SWIFT) sequence is combined with the Look-Locker method to map T1 of IONPs in high concentrations.

Methods

T1 values of agar containing IONPs in different concentrations were measured with the SWIFT Look-Locker method and with inversion recovery spectroscopy. Precisions of Look-Locker and variable flip angle (VFA) methods were compared in simulations.

Results

The measured R1 (=1/T1) has a linear relationship with IONP concentration up to 53.6 mM of Fe. This concentration exceeds concentrations measured in previous work by almost an order of magnitude. Simulations show SWIFT Look-Locker method is also much less sensitive to B1 inhomogeneity than the VFA method.

Conclusions

SWIFT Look-Locker can accurately measure T1 of IONP concentrations ≤53.6 mM. By mapping T1 as a function of IONP concentration, IONP distribution maps might be used in the future to plan effective magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia therapy.

Keywords: SWIFT, iron oxide nanoparticles, T1 mapping, positive contrast, Look-Locker, magnetic hyperthermia

Introduction

Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have proven to be useful in a variety of MRI applications (1,2). The vast majority of MRI applications of IONPs exploit their T2* and T2 shortening properties to create negative contrast that gives qualitative information about the location of the particles (3). However, concentrations of IONPs can be quantified only when the T2* (or T2) is long enough to be imaged when using traditional (echo-based) pulse sequences.

MRI pulse sequences capable of preserving signal from spins with ultra-short T2* have been developed in recent years, like UTE (4,5), ZTE (6-8), Sweep imaging with Fourier transform (SWIFT) (9,10), and PETRA (11). These sequences have negligible T2 or T2*-weighting because signals are acquired immediately after or during the excitation pulse. With these sequences, IONPs can be detected and quantified based on the shortening of the longitudinal relaxation time of water (12-14). Recently we showed how to quantify IONPs in a given voxel by measuring the shortening of T1 (15) with increasing IONP concentration. In this way, calibration data were obtained, as needed to convert in vivo T1 maps into IONP concentration maps.

The most common T1 mapping methods are based on inversion recovery (IR), saturation recovery (SR), or variable flip angle (VFA) sequences. In our initial work (15), the T1 of IONPs was measured with the SWIFT sequence using a VFA method. Although the ultra-short T2* signal was preserved and thus the IONP-induced shortening of T1 could be measured, the VFA method still has some limitations. First, because it requires fitting to the Ernst equation (16), an accurate estimation of the excitation flip angle is needed. As such, a separate measurement of the B1 map must usually be performed (17,18). The second constraint is high RF power. The Ernst angle for spins with short T1 due to high IONP concentration can be as high as 20°. To sample the signal curve well, images acquired at 30° or 40° flip angles are needed. In many cases, the practically achievable RF amplitude cannot produce high flip angles with sufficiently short pulse duration to avoid significant flip angle deviation due to relaxation during the pulse (19). Moreover, for in vivo applications, the specific absorption rate (SAR) limitation of the tissue may not permit the use of such sequences using a short repetition time (TR).

One application that requires high concentrations of IONPs is magnetic nanoparticle based hyperthermia (20,21). Magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia is a promising cancer therapy in development and clinical trials. It uses high concentrations of IONPs to heat cancerous tissue when an alternating electromagnetic field is applied (22). Accurate knowledge of the distribution of the IONPs within the patient is crucial for effective and safe treatment planning (23). The IONP concentration required for efficient hyperthermia is generally greater than 18 mM (=1 mg/ml) of Fe. Traditional MR imaging sequences are unable to quantify IONP concentrations in the therapeutic range because above 9 mM of Fe the MR signal is dominated by noise even at the shortest possible echo times due to ultra-short T2* values. The Hounsfield units derived from computed tomography (CT) images provide quantitative density measurements (14), but those values are not sensitive to changes in IONP concentrations at the lower end of the relevant range. MR images, however, are very sensitive to iron oxide IONPs and suffer from the opposing problem (24). A MRI method which is sensitive to the ultra-short T2* signal and has the ability to precisely quantify IONPs at high concentration is desired.

The Look-Locker method is a way to accelerate T1 mapping (25) for both SR and IR methods. With SR and IR methods, although the spins may not be completely saturated or inverted due to the ultra-short T2*, the residual magnetization can be accounted for using a three parameter mono-exponential fitting equation. As compared with the VFA method, dependence on the actual flip angle is much smaller with the Look-Locker method using low flip angle excitation, as will be shown below. The conventional 2D Look-Locker pulse sequence has previously been extended to 3D MRI to achieve better resolution in the third dimension (26,27); however, no 3D Look-Locker in an ultra-short T2* sensitive sequence has been reported before.

In this work, the SR Look-Locker method was embedded in the 3D SWIFT sequence to generate T1-weighted images with positive IONP contrast and to quantify the T1 values of IONPs at varying concentrations in agar with ultra-short T2* and very short T1. The proposed method was compared to the VFA method and the simple spectroscopic IR method.

Methods

Acquisition and reconstruction scheme

The SWIFT sequence, which is a radial k-space sequence operating in the steady state, was used as a read out sequence. The terminals of gradient vectors in k-space were isotropically distributed on a sphere using the Halton approach (28). The total numbers of views (Ntot) were split into Nvs number of view sets (spirals) with Nv views on each.

In the SR Look-Locker method, an adiabatic half passage (AHP) pulse was applied followed by a half-wave cosine-shaped gradient to eliminate net magnetization. Then, the recovery of longitudinal magnetization (Mz(τ)) at increasing times (τ) was read out using a SWIFT sequence with low flip-angle excitation. Data of a single view set with Nv number of views were acquired during one recovery cycle (Figure 1). The saturation and recovery cycles were repeated to acquire data for a total of Nvs view sets. For spins with given relaxation time T1, the longitudinal magnetization is approximately fully recovered after 5 times of the T1. For different T1 values, Nv number can be adjusted to fully sample the recovery curve. In order to generate images along the recovery curve, data of each view set were binned evenly into groups with Nbin views in each bin (time window). Then, data of views in the same time window, but in a different view set, were combined into groups with Nbin × Nvs views (figure 1). N = Nv/Nbin images were generated along with recovery time τ. The effective recovery time was defined as the average recovery time of the Nbin acquired views in each time window (Figure 1).

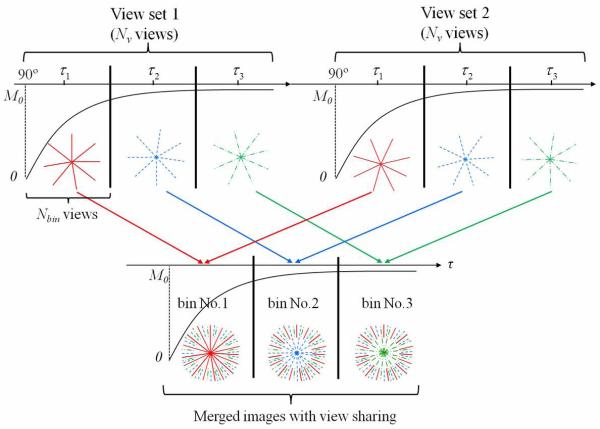

Figure 1.

Example of the Look-Locker acquisition scheme for fast 3D radial T1 mapping. Totally, Nvs (=2 in fig.1) view sets with Nv (=24 in fig.1) views in each set were acquired. Each predefined time window (with Nbin views) along the recovery curve was sampled with Nbin*Nvs (=8*2 in fig.1) unique views. To reconstruct an image from a given time point along the recovery curve, all the projections acquired during that time window are used. The outer extents of k-space, which are undersampled, were filled in with data from all other time windows (in black). The center part of k-space were filled only with data acquired in the given time window (in red, blue and green separately). The view order for each recovery curve was preset to make the total views for single time window in a Halton distribution. Nv/Nbin (=3 in fig.1) images were reconstructed.

To shorten the scan time, a view-sharing reconstruction was used (Figure 1). The center half of k-space was filled only with data acquired in the given time bin. The outer half (where the Nyquist criterion would be violated) was filled with data from all acquired projections. Since the whole k-space was acquired along the recovery curve, the signal intensity of the outer half of k-space needs to be adjusted to match the corresponding inner half of k-space data. A signal ratio was defined as the ratio of the highest intensity measured in the averaged projections (frequency space) using only the k-space data within the corresponding window (i.e., without view sharing). The signal ratio was then used to match the corresponding outer k-space data. Since the outer part is only half of the total k-space, the intensity matching should not significantly influence image contrast. This view sharing method allows all images to be fully sampled with adequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), but yields contrast that is dominated by the small time window within which the center parts of k-space were acquired (29-31). Using N images along the recovery curve, T1eff maps were generated by performing three-parameter non-linear least squares fitting on a pixel-by-pixel basis to the saturation-recovery curve,

| [1] |

The T1 map was then calculated according to the equation,

| [2] |

Experimental sample

The relaxation phantom was constructed from six 5-mm NMR tubes containing Ferrotec EMG-308 iron-oxide nanoparticles (Ferrotec USA Corp., Bedford, NH) of different known concentrations. Specifically, IONP concentrations ranged from 0.0 to 53.6 mM of Fe (equivalent to 0.0 to 3.0 mg Fe/ml) in 1% agar solution (Figure 3b). These tubes were immersed in deionized water within a 3 cm diameter tube.

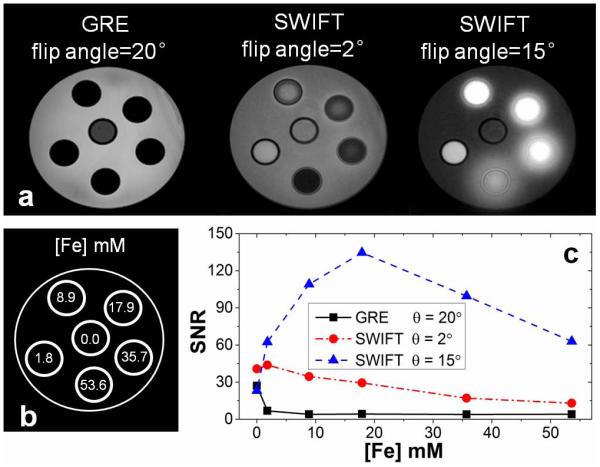

Figure 3.

(a) Images of gradient echo and SWIFT in the presence of high IONP concentrations. The SWIFT images are normal SWIFT images acquired at TR = 2.6 ms and bandwidth = 125 kHz with matched resolution with GRE (matrix = 256×256×256). (b) Concentration for different tubes. (c) The SNR plots. GRE sequence reaches the noise floor at 9 mM; The SNR for SWIFT sequence at 15° remains well above the IONP-free water signal intensity even at 53.6 mM.

Data acquisition

Measurements were performed using a 9.4T magnet equipped with a DirectDrive scanner (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All images were acquired with a volume transmit/receive coil (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The pulse duration (Tp) of the AHP was 500 μs. Other SWIFT sequence parameters were: TR = 1.13 ms, flip angle θ = 1°, spectral width = 125 kHz, field-of-view (FOV) = 50 × 50 × 150 mm3, and image matrix size = 128 × 128 × 128 × 64 (x,y,z,t). The total scan time for one complete SWIFT Look-Locker experiment is about 9 min. Due to the large range of the IONP concentration, experiments with two different view settings were done to fully sample the recovery curves correspondingly (a slash sign is used to separate these two parameter sets). 512/128 (Nvs) view sets with 1024/4096 (Ns) view orders in each view set were totally acquired. For these two view settings, one is with longer total recovery time (Trecovery = 4596 ms) for longer T1, and the other is with shorter total recovery time (Trecovery = 1151 ms) for shorter T1. In each view set, 16/64 (Nbin) views in one time window were binned in a group. So, each time window was sampled with 8192/8192 (Nvs *Nbin) total views here. Although two view settings with different Nbin were used, acquisitions using multiple view settings should not be required except when IONPs are distributed in a large concentration range, as in the phantom study. Most often, the view setting can be adjusted to give optimal coverage of the probable T1 range to permit measurement using one view setting. To reconstruct an image, the center half of k-space was filled only with data acquired in the given time window. The outer half was filled with data from all acquired projections after intensity matching. Totally, 64 (N) images along the recovery curve for different recovery time were reconstructed.

For comparison purposes, T2*-weighted images were also acquired using a gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequence with the following parameters: TR = 4.86 ms, TE = 2.45 ms, θ = 20°, FOV = 50 × 50 × 150 mm3, matrix size = 256 × 256 × 256, and spectral width = 100 kHz.

The T1 values for IONPs phantoms measured by Look-Locker SWIFT were also compared to the results obtained with the gold standard method: the spectroscopic inversion recovery experiment, with spectral width of 100 kHz and inversion hard pulse duration of 100 μs. Furthermore, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and the center frequency of the water resonance of each tube at different IONP concentration were measured individually using spectroscopy, with spectral widths of 10 to 190 kHz and hard pulse durations of 10 to 40 μs for different concentrations. The T2* was calculated based on the measured FWHM.

Error analysis of B1 dependence

Fitting simulations were done on spins with T1 = 500 ms to investigate the possible systematic error of the SR Look-Locker and VFA methods. No noise was added to the simulation. B1 deviation (±20%) was set to both methods. The simulated data of the VFA measurement in 7 different flip angles were fitted to the Ernst equation with two unknown parameters (T1 and spin density). Accordingly, the flip angle θ for the Look-Locker simulation was set to 1°. The TR for the VFA and Look-Locker methods were set to 2 ms and 1 ms, respectively. The fitted T1 values were compared to the actual T1 to get the measurement error in percentage.

Results

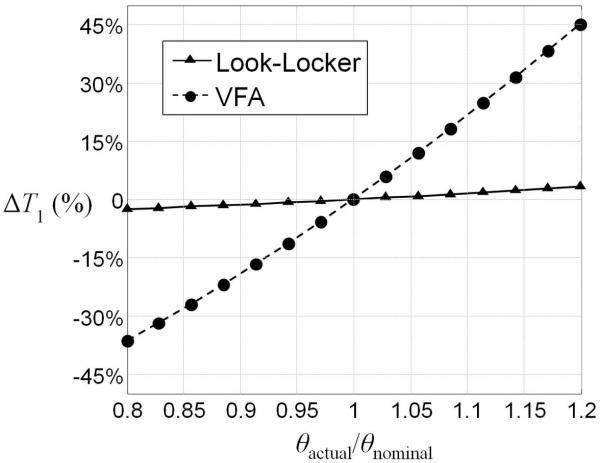

The error in fitting the simulated data for VFA and Look-Locker method is shown in Fig. 2. Note that the VFA method is very sensitive to flip angle error. When the actual flip angle deviates by 20% from the nominal one, the T1 error without accounting for noise can be more than 35% in the VFA case. However, it was only less than 3% in the Look-Locker method when the nominal excitation flip angle was 1°.

Figure 2.

Error analysis of VFA method and Look-Locker method with flip angle deviating from 0.8 to 1.2 of the real value.

Images of the IONP phantom using GRE and SWIFT sequences are shown in Fig. 3a. The iron concentrations of each tube in the images are shown in Fig. 3b. The average SNR for each tube is plotted versus its concentration in Fig. 3c. The signal intensity in the GRE image is at the level of background noise at 8.9 mM and higher concentrations. In SWIFT images acquired with 15° flip angle, the SNR increases up until 17.9 mM and then slowly decreases, but remains well above the IONP-free water signal intensity up to 53.6 mM. The blurring or apparent blooming effect around the tubes with high IONP concentrations in the third image of Fig. 3a results from two sources: 1) line broadening due to the ultra-short T2*, and 2) a frequency offset due to the high iron content of the tube.

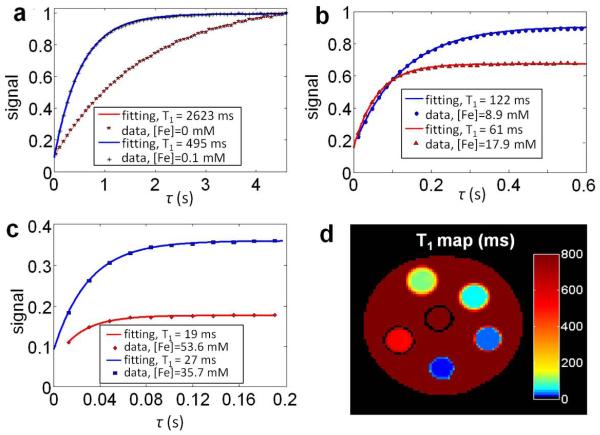

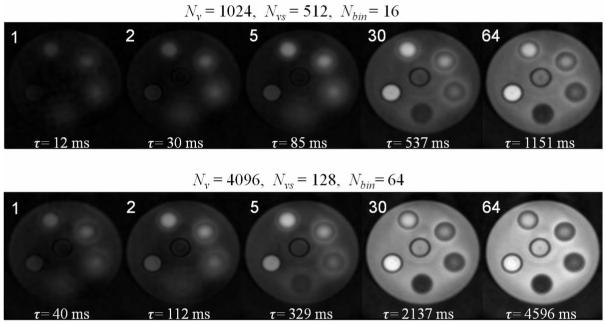

A slice from the T1 map of the IONP phantom with 128×128 in-plane matrix size is shown in Fig. 4d. Example plots of the recovering signal for IONPs of different concentrations are shown in Figs. 4a, b, and d. Images at different recovery time τ are shown in Fig. 5 for two view settings with different Nbin values. For IONP tubes with higher concentrations, the settings for the first image series with smaller Nbin allowed capture of more data points on the initial part of the recovery process.

Figure 4.

(a), (b) & (c) Examples of the T1 recovery curves are plotted with the resulting fits. τ is the recovery time. The symbols are the average voxel values from images and the solid lines are the fittings from the non-linear least squares algorithm. (d) SWIFT T1 map of agar with high IONP concentrations as illustrated in fig. 3b.

Figure 5.

Example images of the SWIFT Look-Locker method along the recovery curves. First column is for shorter recovery curve with total recovery time = 1151 ms. Second column is for longer recovery curve with total recovery time = 4596 ms. The numbers on the images show the number of the time window the images belong to.

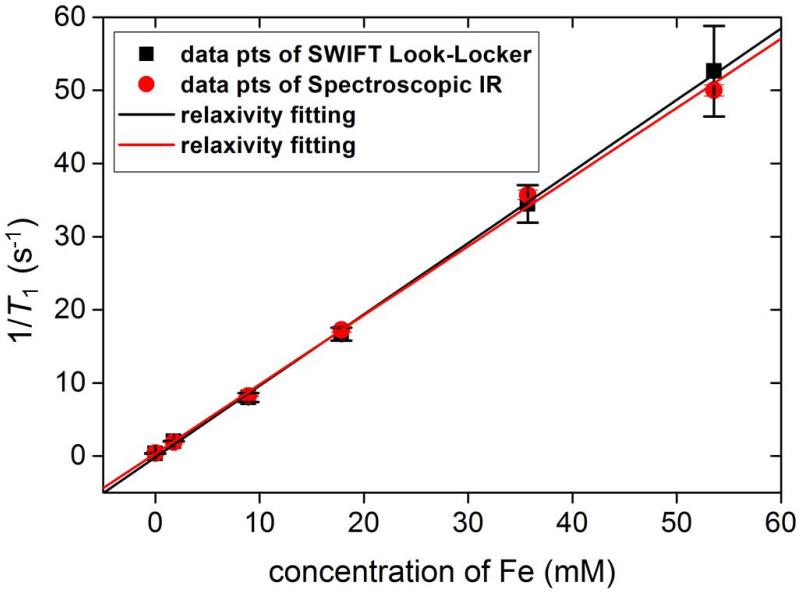

Table 1 lists the average T1 values and standard deviations for tubes with different concentrations measured by both SWIFT Look-Locker and spectroscopic inversion recovery. The crosses in Table 1 indicate data using those specific settings were not suitable for fitting. Fig. 6 presents the R1 (=1/T1) dependence on iron concentration. The data can be fitted well by a linear equation. The relaxivities were fitted from data in Fig. 6 and shown in Table 1. Measurements performed with SWIFT Look-Locker agree well with those obtained with the spectroscopic IR sequence. The T2* values are also given in Table 1.

Table 1. T1 (ms) and T2* (ms) measured in the IONP phantom.

| [Fe] (mM*) | 0 | 1.8 | 8.9 | 17.9 | 35.7 | 53.6 | Relaxivity r1 (s−1mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWIFT Look-Locker (Nbin= 64) |

2720±280 | 495±10 | 125±9 | 63±3 | × | × | 0.977 (R2=0.9997) |

| SWIFT Look-Locker (Nbin= 16) |

× | × | 121±7 | 60±3 | 29±2 | 19±2 | |

| Spectroscopic IR |

2483±24 | 526±2 | 122±1 | 58±1 | 28±0.5 | 20±0.3 | 0.945 (R2=0.9990) |

| T2* (ms) | 11.37 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.077 | 0.046 | 0.034 |

1 mM Fe is approximately 0.056 mg Fe/mL

Figure 6.

R1 (1/ T1) is plotted versus the concentration of iron to determine if T1 could be used as a measurement for determining IONP concentration. The data shows that the R1 and the concentration have a linear relationship.

Discussion and conclusions

This work demonstrates that SWIFT can create images with positive IONP contrast, and that SWIFT Look-Locker can quantify high local concentrations of IONPs. The images provide qualitative information about the distribution of IONPs up to concentrations of 53.6 mM as used in Magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia. Traditional echo-base pulse sequences show only noise at these high IONP concentrations. In addition to this qualitative imaging information, SWIFT allows concentration measurement through T1 mapping. As indicated by Fig. 3, iron quantification was not feasible above 9 mM with the conventional gradient-echo sequence. By having no “echo” and being able to capture signal from spins with very short T2* values, SWIFT can probe the effect on T1 as the concentration of iron changes. Although only the SWIFT sequence was used for read out in this work, other ultra-short T2*-sensitive sequences using radial sampling should also work well with the present Lock-Locker scheme to achieve similar T1 mapping.

From the error analysis in Fig. 2, it is apparent that the Look-Locker method is much less sensitive to the flip angle deviation which can come from both B1 inhomogeneity and ultra-short T2*. Actually, from equation [2], the contribution from the second term will decrease when the flip angle is smaller. Hence, the influence of flip angle deviation on T1 will reduce. Also, a smaller flip angle gives longer T1eff which allows more time to sample the recovery curve for short T1 spins. On the contrary, for the VFA method, at such a high concentration of the IONPs, it is extremely difficult to map the B1 inhomogeneity for correction of the T1 measurement due to the ultra-short T2*. So, the B1 dependence of the VFA method is a significant disadvantage for T1 mapping of IONPs in high concentrations.

In addition to its greater tolerance to B1 inhomogeneity, SWIFT Look-Locker can make accurate measurements of IONPs to much higher concentrations than the VFA-SWIFT method. In previous work, the maximum IONP concentration measured with VFA-SWIFT was 7 mM. Here, SWIFT Look-Locker permitted measurement of IONP concentrations as high as 53.8 mM. In addition, even with the same concentration, the SAR of the SWIFT Look-Locker experiment is much smaller than that of VFA-SWIFT, due to the low flip angle (1° in this paper) applied. Both the insensitivity to B1 inhomogeneity and relatively low SAR of SWIFT Look-Locker are significant advantages, particularly for clinical applications.

The signal intensity measured at long τ represents a nearly fully relaxed state, and as such, the fully relaxed signal intensities might be expected to be the same in all containers since the proton concentration varied very little. However, the fully relaxed signal intensity decreased significantly as the IONP concentration increased (Fig. 4). This finding is consistent with image blur caused by the ultra-short T2* and/or an off-resonance displacement of signal. To investigate these possibilities, the images were reconstructed using different resonance frequencies (see supplemental material). The blur from each tube was reduced significantly, although not eliminated, when reconstructing with the specific resonance frequency of the given tube as measured by spectroscopy. Thus, besides the off-resonance effect, the second mechanism (line broadening) must be responsible for some of the blur. Although blur was observed in the SWIFT image at high flip angle (Fig. 3), the blur in the measured T1 map was much less. The latter was due to the low flip angle used in the SWIFT Look-Locker experiment, which caused the signal of the surrounding water to dominate. In the future, the image blur can be reduced by using a higher acquisition bandwidth.

The T1 map acquired in this study was defined in a 128×128×128 image matrix using the present acquisition and reconstruction setting. If higher resolution is wanted, view settings can be adjusted to acquire more points in each view. To keep the scan time the same, less views will be acquired. Although the number of views needs to be reduced, by doing view sharing, maps with higher resolution can be achieved. The view sharing strategy does place an upper limit on the spatial resolution at which the T1 map can be obtained (32). Emerging compressed sensing techniques could recover some of this spatial resolution at the expense of increase complexity of the reconstruction (33).

Translating these techniques into animal and human studies should not create additional problems. SWIFT uses a low flip angle readout that will not reach SAR limits, and the total scan time is reasonable for clinical studies. Therefore, SWIFT Look-Locker T1 mapping should prove to be valuable tool in Magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia research and practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Sponsors: MN Futures Grant (University of Minnesota); NSF/CBET-1066343; NIH P41 EB015894.

Reference

- 1.Corot C, Robert P, Idee JM, Port M. Recent advances in iron oxide nanocrystal technology for medical imaging. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2006;58:1471–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu W, Frank JA. Detection and quantification of magnetically labeled cells by cellular MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlpeter R, Dahnke H, Matuszewski L, Persigehl T, von Wallbrunn A, Allkemper T, Heindel WL, Schaeffter T, Bremer C. R2 and R2*mapping for sensing cell-bound superparamagnetic nanoparticles: In vitro and murine in vivo testing. Radiology. 2007;245:449–457. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergin CJ, Pauly JM, Macovski A. Lung Parenchyma - Projection Reconstruction MR Imaging. Radiology. 1991;179:777–781. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.3.2027991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomo. 2003;27:825–846. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafner S. Fast imaging in liquids and solids with the Back-projection Low Angle ShoT (BLAST) technique. Magn Reson Imag. 1994;12:1047–1051. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)91236-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madio DP, Lowe IJ. Ultra-Fast Imaging Using Low Flip Angles and Fids. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:525–529. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiger M, Brunner DO, Dietrich BE, Muller CF, Pruessmann KP. ZTE imaging in humans. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:328–332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Park JY, Garwood M. Fast and quiet MRI using a swept radiofrequency. J Magn Reson. 2006;181:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garwood M, Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Chamberlain R, Moeller S, Kobayashi N, Lehto L, Zhang J, O’Connell R, Tesch M, Nissi M, Ellermann J, Nixdorf D. Capturing Signals from Fast-relaxing Spins with Frequency-Swept MRI: SWIFT. Encycloepedia of Magnetic Resonance: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grodzki DM, Jakob PM, Heismann B. Ultrashort echo time imaging using pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA) Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:510–518. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon GH, Bauer J, Saborovski O, Fu YJ, Corot C, Wendland MF, Daldrup-Link HE. T1 and T2 relaxivity of intracellular and extracellular USPIO at 1.5T and 3T clinical MR scanning. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girard OM, Du J, Agemy L, Sugahara KN, Kotamraju VR, Ruoslahti E, Bydder GM, Mattrey RF. Optimization of Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Detection Using Ultrashort Echo Time Pulse Sequences: Comparison of T1, T2*, and Synergistic T1-T2* Contrast Mechanisms. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:1649–1660. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou R, Idiyatullin D, Moeller S, Corum C, Zhang H, Qiao H, Zhong J, Garwood M. SWIFT detection of SPIO-labeled stem cells grafted in the myocardium. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1154–1161. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Corum CA, Idiyatullin D, Garwood M, Zhao Q. T1 estimation for aqueous iron oxide nanoparticle suspensions using a variable flip angle SWIFT sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:341–347. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst RR, Anderson WA. Application of Fourier transform to magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Rev Sci Instrum. 1966;37:93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng HLM, Wright GA. Rapid high-resolution T-1 mapping by variable flip angles: Accurate and precise measurements in the presence of radiofrequency field inhomogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:566–574. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dathe H, Helms G. Exact algebraization of the signal equation of spoiled gradient echo MRI. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:4231–4245. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/15/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carl M, Bydder M, Du J, Takahashi A, Han E. Optimization of RF excitation to maximize signal and T2 contrast of tissues with rapid transverse relaxation. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:481–490. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gneveckow U, Jordan A, Scholz R, Bruss V, Waldofner N, Ricke J, Feussner A, Hildebrandt B, Rau B, Wust P. Description and characterization of the novel hyperthermia- and thermoablation-system MFH (R) 300F for clinical magnetic fluid hyperthermia. Med phy. 2004;31:1444–1451. doi: 10.1118/1.1748629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan A, Scholz R, Wust P, Fahling H, Felix R. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia (MFH): Cancer treatment with AC magnetic field induced excitation of biocompatible superparamagnetic nanoparticles. J Magn Magn Mater. 1999;201:413–419. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosensweig RE. Heating magnetic fluid with alternating magnetic field. J Magn Magn Mater. 2002;252:370–374. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johannsen M, Gneueckow U, Thiesen B, Taymoorian K, Cho CH, Waldofner N, Scholz R, Jordan A, Loening SA, Wust P. Thermotherapy of prostate cancer using magnetic nanoparticles: Feasibility, imaging, and three-dimensional temperature distribution. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1653–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy PA, Henkelman RM. Transverse Relaxation Rate Enhancement Caused by Magnetic Particulates. Magn Reson Imag. 1989;7:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(89)90549-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Look D, Locker DR. Time saving in measurement of NMR and EPR relaxation times. Rev Sci Instrum. 1970;41:250–251. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson E, McKinnon G, Lee TY, Rutt BK. A fast 3D look-locker method for volumetric T1 mapping. Magn Reson Imag. 1999;17:1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Scheidegger R, Wu Y, Vu A, Prasad PV. Accuracy of T1 measurement with 3-D Look-Locker technique for dGEMRIC. J Magn Reson Imag. 2008;27:678–682. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong T-T, Luk W-S, Heng P-A. Sampling with Hammersley and Halton Points. J Graph Tools. 1997;2:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altbach MI, Outwater EK, Trouard TP, Krupinski EA, Theilmann RJ, Stopeck AT, Kono M, Gmitro AF. Radial fast spin-echo method for T2-weighted imaging and T2 mapping of the liver. J Magn Reson Imag. 2002;16:179–189. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altbach MI, Bilgin A, Li ZQ, Clarkson EW, Trouard TP, Gmitro AF. Processing of radial fast spin-echo data for obtaining T-2 estimates from a single k-space data set. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:549–559. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters DC, Botnar RM, Kissinger KV, Yeon SB, Appelbaum EA, Manning WJ. Inversion recovery radial MRI with interleaved projection sets. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1150–1156. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsao J, Kozerke S. MRI temporal acceleration techniques. J Magn Reson Imag. 2012;36:543–560. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen MS, Sorensen TS. Gadgetron: An open source framework for medical image reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1768–1776. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.