Abstract

Background/Objectives

Elderly surgical patients have an increased risk for complications and mortality, however, the “big picture” of their surgical care and complications has not been well described. In this study of the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry, our hypothesis was that procedures, hospitals visited, and complications would differ by decade in the elderly and in comparison to younger adults.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

Anesthesia Quality Institute’s National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry (NACOR) is the largest repository of anesthesia cases from academic and community hospitals and includes all insurance and facility types across the United States.

Participants

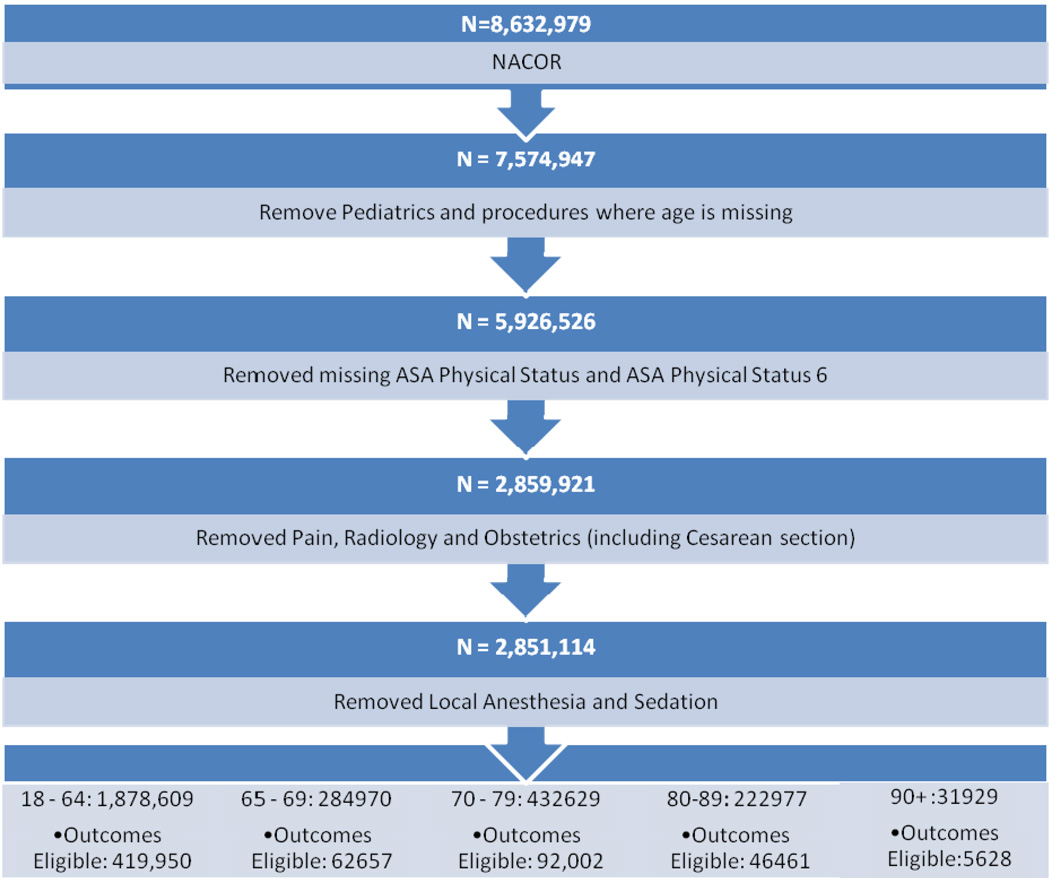

8,632,979 cases from January 2010 to March 2013 were acquired. After exclusion of age<18, non-applicable locations, and brain death, 2,851,114 remained and were placed into age categories: 18–64, 65–69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90+years old.

Measurements

Patient, surgical, anesthetic and hospital descriptors, short-term outcomes (major complications, mortality at <48 hours)

Results

The largest number of seniors had surgery in medium-sized community hospitals. The oldest age group (90+) underwent the smallest range of procedures; hip fracture, hip replacement, and cataract procedures comprised greater than 35% of all surgeries. Younger old patients underwent these procedures plus a significant proportion of spinal fusions, cholecystectomy, and knee surgery. Mortality and complications was increased in the geriatric groups relative to younger adults. Exploratory laparotomy had the highest proportion of death in any age category except 90+, where small bowel resection predominated. The proportion of emergency surgery and the amount of mortality associated with emergency surgery was 30% higher in the oldest (90+ group) compared to adults age 18–64.

Conclusion

This paper reports the pattern of surgical procedures, complications and mortality found in NACOR which one of the few datasets which has both community hospitals and all insurance types. Because the outcomes portion is under development it is not currently possible to investigate the relationship between hospital type and complications or mortality. However, this study underscores the magnitude of geriatric surgery which occurs in community hospitals and points to the need for future investigation in this area.

Keywords: surgery, outcomes, anesthesia, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Elderly surgical patients represent a large proportion of the overall surgical population; information gathered from the National Hospital Discharge Survey reported that in 2006 patients 65 years of age and older accounted for 35.3% of all inpatient procedures, and 32.2% of all outpatient procedures (1, 2). However, there is a relative paucity of scientific literature which examines perioperative health care patterns in the oldest- old patients (≥75 years of age) despite their high risk for postoperative complications and mortality. Single- and even multi-center studies often have inadequate sample sizes to describe this surgical population in-depth(3). The magnitude and risk of surgery for the aging population underscores the importance of identifying high impact areas to study in order to improve perioperative outcomes in the future. Research has addressed patient- level outcomes in the elderly such as: cardiac risk stratification, delirium assessments, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, frailty and pneumonia (4–8). However, from the policy and planning perspective, it is also important to understand whether these risk factors are ameliorated or worsened by where elderly patients have surgery and what procedures they undergo (9). While some of the risk is due to the physiology of aging (e.g. decreased cardiac reserve), or a composite of conditions (frailty), the perioperative risk of elderly patients is a more complicated question including factors which may not be amenable to intervention (e.g. genetics) and those that may be due to regional variation or resource based clinical decisions (10–13).

An example of the important questions raised through the epidemiologic study of geriatric surgical patients examined the incidence of surgical procedures in the year prior to death(14). They found that end of life “surgical intensity” varied significantly by region of the country and by age after adjustment for comorbidity. Also, age was inversely proportional to number of procedures in the final year of life, which the authors commented might mean that provider’s thresholds for providing intervention may change with age. This study opened the discussion of what is appropriate care for dying elderly patients, and that whether patients receive surgery may be a function of where they live.

The epidemiology of geriatric surgical and anesthetic care is difficult to define in the absence of a specialized surveillance system; in anesthesiology, this is beginning to change. Multicenter anesthesiology outcomes research consortiums including the Outcomes Research Consortium led by D. Sessler at the Cleveland Clinic and the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) lead by Kevin Tremper and Sachin Kheterpal have collected data and produced important findings on a variety of perioperative issues(15–19). In 2010 The National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry (NACOR) was created by the Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI) with support from the American Society of Anesthesiologists. This database is unique because it is the largest repository of clinical anesthesia cases, and because it includes data from both academic and private hospitals in all of the United States Census regions(20). NACOR currently contains more than 10 million anesthetic records across age groups, insurance type, and facility type, harvested from electronic billing and clinical data to capture practice and patient profiles. The database holds the potential for linking facility- level information with patient- level preoperative risk factors, intraoperative events, and postoperative complications. This paper uses NACOR to define the demographics and outcomes of older surgical patients.

In this paper we report the first study using the NACOR database to compare the distribution of cases and outcomes in five age categories: 18–64, –69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90+.Our hypothesis is that the procedures, patterns of care, and outcomes will be different between age groups. Further, we believe that systematic differences in how older patients are cared for will be of use to policy makers, funding institutes, and researchers seeking to target high yield areas.

METHODS

After obtaining local IRB determination of exemption from human subjects review at the Icahn School of Medicine, NACOR data from January 2010 to March 2013 (n=8,632,979 cases) were acquired. The dataset included all patients undergoing surgery and anesthesia in addition to descriptors of the hospital and practice where the surgery occurred. While the NACOR extract is a de-identified database, to assure confidentiality of patient records, practices were listed by state only and no zip codes were provided. We eliminated pediatric patients, cases where the age of the patient was not listed, cases that were performed in chronic pain clinics and other non-applicable locations (e.g. labor and delivery), and patients who were brain dead and underwent organ harvest. The remaining 2,851,114 patients were categorized into five age groups: 18–64, 65–69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90+ (Figure 1). The data was coded to group hospitals by size and to separate university and community hospitals. Clinical Classifications Software developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project was used to group CPT codes into 244 categories for the purpose of analysis (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Inclusion in the Study

We examined patient, surgical, anesthetic and hospital descriptors of each age group: gender, ASA status, whether the surgery was in- or out-patient, emergency or elective, university v. community hospital and hospital size, and type of anesthesia provided (Table 1). The Chi-squared test was used to assess the difference in proportions for categorical variables (gender, inpatient vs. outpatient, emergency vs. elective) between age groups. The ten most common procedures (by percentage) were noted for each group (Table 2). The data analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 (Copyright, SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the NACOR Sample

| Age Group 18–64 | Percent | Age Group 65–69 | Percent | Age Group 70–79 | Percent | Age Group 80–89 | Percent | Age Group 90+ | Percent | pValue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,878,609 | 284,970 | 432,629 | 222977 | 31929 | ||||||

| Mean | 45.72 | 66.98 | 74.15 | 83.58 | 92.39 | ||||||

| Standard Deviation | 12.59 | 1.41 | 2.86 | 2.71 | 2.45 | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Female | 1,140,022 | 60.68 | 152,986 | 53.68 | 231,596 | 53.53 | 124,319 | 55.74 | 20409.00 | 63.92 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 705,507 | 37.55 | 127,746 | 44.83 | 194,415 | 44.94 | 95,394 | 42.78 | 11112.00 | 34.80 | |

| Not Listed | 33,080 | 1.76 | 6,618 | 1.49 | 6,618 | 1.53 | 3,264 | 1.46 | 408.00 | 1.28 | |

| Location Status | |||||||||||

| Outpatient | 1,090,647 | 58.06 | 146,599 | 51.44 | 221,025 | 51.09 | 106,673 | 47.84 | 11578.00 | 36.26 | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient | 518,786 | 27.62 | 100,956 | 35.43 | 157,063 | 36.30 | 88,791 | 39.82 | 15641.00 | 48.99 | |

| Not Listed | 269,176 | 14.33 | 37,415 | 13.13 | 54,541 | 12.61 | 27,513 | 12.34 | 4710.00 | 14.75 | |

| ASA Status | |||||||||||

| ASA 1/2 | 1,409,485 | 75.03 | 156,082 | 54.77 | 207,904 | 48.05 | 85,675 | 38.42 | 9891.00 | 30.98 | <0.0001 |

| ASA 3 | 398,236 | 21.20 | 106,540 | 37.39 | 183,751 | 42.47 | 109,510 | 49.11 | 16673.00 | 52.22 | |

| ASA 4 | 68,999 | 3.67 | 21,914 | 7.69 | 40,178 | 9.29 | 27,316 | 12.25 | 5285.00 | 16.55 | |

| ASA 5 | 1,889 | 0.10 | 434 | 0.15 | 796 | 0.18 | 476 | 0.21 | 80.00 | 0.25 | |

| Anesthesia Type | |||||||||||

| General | 1,453,390 | 77.37 | 187,447 | 65.78 | 260,491 | 60.21 | 126,922 | 56.92 | 18055.00 | 56.55 | <0.0001 |

| Epidural/Spinal | 41,204 | 2.19 | 12,248 | 4.30 | 19,573 | 4.52 | 11,370 | 5.10 | 2370.00 | 7.42 | |

| Regional | 30,440 | 1.62 | 6,312 | 2.21 | 9,643 | 2.23 | 5,242 | 2.35 | 927.00 | 2.90 | |

| Monitored Anesthesia Care | 156,682 | 8.34 | 45,145 | 15.84 | 88,552 | 20.47 | 49,378 | 22.14 | 5983.00 | 18.74 | |

| Sedation | 15,052 | 0.80 | 3,088 | 1.08 | 5,533 | 1.28 | 3,556 | 1.59 | 671.00 | 2.10 | |

| Not Listed | 181,841 | 9.68 | 30,730 | 10.78 | 48,837 | 11.29 | 26,509 | 11.89 | 3923.00 | 12.29 | |

| Hospital Utilization | |||||||||||

| University Hospital | 134,945 | 7.18 | 19,165 | 6.73 | 30,316 | 7.01 | 13,813 | 6.19 | 1569.00 | 4.91 | <0.0001 |

| *Large Facility | 394,045 | 20.98 | 56,275 | 19.75 | 83,601 | 19.32 | 43,973 | 19.72 | 7153.00 | 22.40 | |

| *Medium Facility | 993,455 | 52.88 | 156,203 | 54.81 | 234,281 | 55.64 | 124,062 | 55.64 | 18406.00 | 57.65 | |

| *Small Facility | 76,108 | 4.05 | 12,700 | 4.46 | 20,447 | 4.73 | 9,424 | 4.23 | 1293.00 | 4.05 | |

| Office / Freestanding | 280,056 | 14.91 | 40,627 | 14.26 | 63,984 | 14.79 | 31,705 | 14.22 | 3508.00 | 10.99 | |

| Hospital Utilization (Emergency Care Only) | |||||||||||

| Total Emergency Surgery | 88,453 | 4.71 | 11,588 | 4.06 | 18,129 | 4.19 | 11,609 | 5.21 | 2337.00 | 7.32 | <0.0001 |

| University Hospital | 2,564 | 2.90 | 377 | 3.25 | 685 | 3.78 | 310 | 2.67 | 46.00 | 1.97 | |

| *Large Facility | 16,505 | 18.66 | 1,440 | 12.43 | 2,346 | 12.94 | 1,763 | 15.19 | 417.00 | 17.84 | |

| *Medium Facility | 47,562 | 53.77 | 7,278 | 62.81 | 11,462 | 63.22 | 7,693 | 66.27 | 1655.00 | 70.82 | |

| *Small Facility | 1,086 | 1.23 | 65 | 0.56 | 97 | 0.54 | 110 | 0.95 | 36.00 | 1.54 | |

| Office / Freestanding | 20,737 | 23.44 | 2,428 | 20.95 | 3,539 | 19.52 | 1,733 | 14.93 | 183.00 | 7.83 | |

Note: Large Facility = >500 Beds; Medium Facility = 100 – 500 Beds; Small Facility = <100 Beds

Table 2.

Ten Most Common Procedures by Age Group

| Age Group 18–64 | ||

| Procedure | N | Percent |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 97,303 | 5.18 |

| Hysterectomy abdominal and vaginal | 75,372 | 4.01 |

| Excision of semilunar cartilage of knee | 72,598 | 3.86 |

| Other OR therapeutic procedures on joints | 66,179 | 3.52 |

| Other OR therapeutic procedures on skin and breast | 60,166 | 3.20 |

| Spinal fusion | 56,646 | 3.02 |

| Other diagnostic procedures female organs | 49,564 | 2.64 |

| Arthroplasty knee | 45,907 | 2.44 |

| Laminectomy excision intervertebral disc | 45,739 | 2.43 |

| Other excision of cervix and uterus | 43,382 | 2.31 |

| Age Group 65–69 | ||

| Procedure | N | Percent |

| Lens and cataract procedures | 32,747 | 11.49 |

| Arthroplasty knee | 19,380 | 6.80 |

| Hip replacement total and partial | 9,389 | 3.29 |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 9,307 | 3.27 |

| Spinal fusion | 9,018 | 3.16 |

| Excision of semilunar cartilage of knee | 7,332 | 2.57 |

| Laminectomy excision intervertebral disc | 6,464 | 2.27 |

| Inguinal and femoral hernia repair | 5,723 | 2.01 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) | 5,723 | 2.01 |

| Other hernia repair | 5,587 | 1.97 |

| Age Group 70–79 | ||

| Procedure | N | Percent |

| Lens and cataract procedures | 73,938 | 17.09 |

| Arthroplasty knee | 29,331 | 6.78 |

| Hip replacement total and partial | 15,299 | 3.54 |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 13,240 | 3.06 |

| Spinal fusion | 11,861 | 2.74 |

| Laminectomy excision intervertebral disc | 10,829 | 2.50 |

| Transurethral excision drainage or removal urinary obstruction | 10,241 | 2.37 |

| Inguinal and femoral hernia repair | 9,625 | 2.22 |

| Other therapeutic procedures on eyelids conjunctiva cornea | 8,491 | 1.96 |

| Colorectal resection | 8,337 | 1.93 |

| Age Group 80–89 | ||

| Procedure | N | Percent |

| Lens and cataract procedures | 39,004 | 17.49 |

| Treatment fracture or dislocation of hip and femur | 15,080 | 6.76 |

| Arthroplasty knee | 10,537 | 4.73 |

| Hip replacement total and partial | 9,147 | 4.10 |

| Transurethral excision drainage or removal urinary obstruction | 7,817 | 3.51 |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 6,973 | 3.13 |

| Colorectal resection | 5,477 | 2.46 |

| Inguinal and femoral hernia repair | 5,276 | 2.37 |

| Other therapeutic procedures on eyelids conjunctiva cornea | 4,996 | 2.24 |

| Excision of skin lesion | 4,528 | 2.03 |

| Age Group 90+ | ||

| Procedure | N | Percent |

| Treatment fracture or dislocation of hip and femur | 7,076 | 22.16 |

| Lens and cataract procedures | 3,445 | 10.79 |

| Hip replacement total and partial | 1,553 | 4.86 |

| Transurethral excision drainage or removal urinary obstruction | 1,325 | 4.15 |

| Gastrostomy temporary and permanent | 981 | 3.07 |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 908 | 2.84 |

| Colorectal resection | 847 | 2.65 |

| Excision of skin lesion | 824 | 2.58 |

| Other therapeutic procedures on eyelids conjunctiva cornea | 796 | 2.49 |

| Ureteral catheterization | 660 | 2.07 |

In addition to NACOR’s relatively complete demographic case information, a number of practices also contributed short-term outcomes data. This sample represents approximately 20% of the entire database submitted mostly by large centers that use computerized record keeping which facilitates identification and transmission of outcomes. The available outcomes include complications (e.g. hemodynamic instability), adverse events (e.g. anaphylaxis), and errors (e.g. medication error, patient wrong site surgery). The outcomes portion of the database also included mortality defined in NACOR as intraoperative death or death during immediate postoperative care. In this study 626,698 cases contributed outcomes which we grouped as major hemodynamic instability, major respiratory complications (defined as postoperative desaturation, airway obstruction, or reintubation, resuscitation), any major adverse outcome, or death within the perioperative period.

RESULTS

The four geriatric categories contributed 34.1% (972505) of all surgeries. Table 1 contains the descriptive characteristics of the patients from these four age groups plus younger adults 18–64 years of age. With increasing age, more of the surgery was done as an inpatient procedure and fewer patients had general anesthesia. Surgery on ASA 5 patients (not expected to survive) was at least as common in the geriatric age groups, and was 2.5 times higher than in the young. About two thirds of the patients in the 90+ group were women, interestingly this proportion was similar to the youngest group which may have been due to gynecologic surgery.

The percentage of patients classified as ASA Physical Status 3 and 4 increased with age (Figure 3). In all groups, except for the 90+, more than 95% of the cases were elective; in this group emergencies comprised 7.32% of the surgical volume (Table 1). Greater than 50% of patients in each age group had surgery in medium sized community hospitals, and more than 20% in large community hospitals. An even larger proportion of emergency surgery occurred in medium sized community hospitals and this was greatest in the 90+ group (>70%).

The most common surgical procedure in the 90+ group was repair of a hip fracture (>20% of all cases) followed by cataract surgery (10%), and hip replacement (>4%) (Table 2). In the younger patients there were a much larger variety of procedures; the largest category only contained 5.18% of the surgery(cholecystectomy), in comparison to the 90+ group where the largest category (treatment of hip fracture) contained >20% of all surgery (Table 2). In the 65–69 and 70–79 year old patients, hip fracture disappears off the list of most common procedures, and hip replacement, coronary artery bypass graft, and spine surgery appear more prominently. In these groups spinal fusion is more common than laminectomy alone (Table 2). The top three procedures in the 65–69 groups are: cataract removal, knee arthroplasty, and hip replacement. The most common procedures in younger people are predominately general (cholecystectomy), orthopedic (knee arthroscopy), and gynecologic surgery.

Mortality at <48 hours increased with age greater than 70; the percentage of 90+ patients who died within 48 hours of surgery was twice that of the young (Table 3). Other complications including major hemodynamic instability or the occurrence of any major adverse outcome increased with age except in the oldest old group who had a similar incidence to the young (Table 3). Table 4 lists the procedures which contributed the largest number of cases to the total mortality for each age group. Among all age groups, exploratory laparotomy accounted a large number of deaths and had the highest case fatality proportion across the age groups except 90+ where small bowel resection had the highest proportion. Emergency procedures were a lower proportion of mortality cases in the young adult group relative to the elderly. In general the list of procedures contributing to the greatest number of fatalities in the oldest group was predominated by those which are highly associated with emergency surgery e.g. small bowel resection, hernia repair, and hip fracture. In the younger old and the young, the list had a mix of both, including exploratory laparotomy, heart valve surgery, and wound debridement.

Table 3.

Outcomes by Age Group

| Outcome Name | Age Group 18–64 |

Percent * |

Age Group 65–69 |

Percent * |

Age Group 70–79 |

Percent * |

Age Group 80–89 |

Percent * |

Age Group >90 |

Percent * |

pValue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Hemodynamic instability | 403 | 0.10 | 112 | 0.18 | 164 | 0.18 | 109 | 0.23 | 5 | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

| Major Respiratory Complication | 460 | 0.11 | 95 | 0.15 | 147 | 0.16 | 87 | 0.19 | 7 | 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Required Resuscitation | 553 | 0.17 | 163 | 0.26 | 229 | 0.25 | 157 | 0.34 | 8 | 0.14 | <0.0001 |

| Died | 115 | 0.03 | 24 | 0.04 | 59 | 0.06 | 27 | 0.06 | 4 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Any major outcome | 2805 | 0.67 | 591 | 0.94 | 900 | 0.98 | 550 | 1.18 | 38 | 0.68 | <0.0001 |

Note: Percent of patients in that age category who experienced the outcome.

Table 4.

Procedures Contributing the Largest Number of Mortality by Age Group

| Age Group 18–64 | ||||

| Mortality | 115 | 419,950 | 0.030 | |

| Procedure | N |

Total Eligible |

Percent * | |

| Exploratory lap | 24 | 1,640 | 1.460 | |

| Heart valve | 7 | 1,732 | 0.404 | |

| Colorectal | 6 | 4,571 | 0.131 | |

| Wound debridement | 6 | 5,112 | 0.117 | |

| Aortic resection | 4 | 369 | 1.080 | |

| Emergency | 21 | 115 | 18.260 | |

| Age Group 65–69 | ||||

| Mortality | 24 | 62,657 | 0.040 | |

| Procedure | N |

Total Eligible |

Percent * | |

| Exploratory lap | 4 | 270 | 1.480 | |

| Heart Valve | 4 | 666 | 0.600 | |

| Colorectal resection | 2 | 1,071 | 0.190 | |

| CABG | 2 | 1,235 | 0.160 | |

| Aortic Resection | 2 | 181 | 1.100 | |

| Emergency | 9 | 24 | 37.500 | |

| Age Group 70–79 | ||||

| Mortality | 59 | 92,002 | 0.060 | |

| Procedure | N |

Total Eligible |

Percent * | |

| Exploratory lap | 12 | 415 | 2.890 | |

| Colorectal resection | 5 | 1,807 | 0.280 | |

| Aortic resection or anastamosis | 6 | 257 | 2.330 | |

| Other vascular | 4 | 810 | 0.490 | |

| Small bowel resection | 3 | 451 | 0.670 | |

| Emergency | 16 | 59 | 27.120 | |

| Age Group 80–89 | ||||

| Mortality | 27 | 46,461 | 0.060 | |

| Procedure | N |

Total Eligible |

Percent * | |

| Cholecystectomy | 5 | 1,282 | 0.390 | |

| Exploratory lap | 4 | 231 | 1.730 | |

| Aortic resection or anastamosis | 2 | 127 | 1.570 | |

| Colorectal resection | 2 | 1,158 | 0.170 | |

| Treatment fracture or dislocation of hip, femur | 3 | 3,331 | 0.090 | |

| Emergency | 7 | 27 | 25.930 | |

| Age Group90+ | ||||

| Mortality | 4 | 5,628 | 0.070 | |

| Procedure | N |

Total Eligible |

Percent * | |

| Treatment of fracture or dislocation of hip, femur | 2 | 1,280 | 0.160 | |

| Small bowel resection | 1 | 55 | 1.790 | |

| Other hernia repair | 1 | 40 | 2.500 | |

| Emergency | 1 | 4 | 25.000 | |

Note: Percent of patients in that age category who experienced the outcome.

DISCUSSION

This is the first use of the NACOR database for research; our study shows that four age groups of elderly having surgery differ from each other and younger patients by distribution of surgical procedures and by outcomes. The oldest age group experiences a smaller range of surgical procedures, with the top ten most common procedures accounting for greater than 30% of all cases. It is unclear whether this is because the oldest patients have already outlived cancer and heart disease (and thus the need for surgery) or because perceived high risk tends to push the distribution of surgery away from elective procedures and toward palliation. Most cases are orthopedic and general surgery occurring at community hospitals and these could be high impact be targets for long term outcomes studies and clinical trials including measures like cognition, frailty, and quality of life.

Mortality and the occurrence of major complications are more common in the oldest group and these occur in a very distinct subset of procedures. Interestingly, the proportion of intraoperative complications in the 90+ group was similar to younger patients, which may be because they tended to undergo smaller less invasive procedures. However, the perioperative mortality rate of this group was the highest; the reason is unclear but may have been related to either patient (e.g. comorbidity, stress response) or systems factors (failure to rescue). The NACOR dataset only includes outcomes from anesthesia groups which volunteer to provide which tend to be larger facilities with computerized record keeping systems. This means this study cannot accurately report the association of facility with mortality in this study since the sample of outcome providers is stilted toward large and academic hospitals. While it appears that the driving force behind this could be the illness associated with emergency surgery, more work is needed to understand whether there are mitigating factors. The relationship between procedure and long term outcomes is not available in this dataset, and may have a different profile than the short term data presented in this paper (21). Understanding the risk-benefit profile of surgery in older patients is critical in triage decisions – which cases to do, which to decline, and which to refer to a specialty center – and in provider and patient education (22,23). It is possible that age bias exists against offering surgery to some very old patients who might otherwise benefit (24).

Our study is the beginning of understanding geriatric risk in the Donabedian paradigm of structure, process, and outcomes as it applies to healthcare (25). For instance, an often misunderstood pattern of healthcare utilization is the impression that academic centers take care of the sickest and most elderly patients. While this may be true by proportion, our data suggests that the largest number of these patients have surgery in medium sized community hospitals. In our data this was also true of emergency surgery in all age categories, and important because a larger percentage of mortality was associated with emergency surgery in the elderly. This distribution of surgical volume is important to recognize because currently most research studies and new interventions take place in teaching institutions. Tinetti et al suggested that our understanding of perioperative risk may be limited by choosing the wrong intervention to study or the wrong age group/population to study a valid intervention (26). Our work highlights the question of whether academic centers should partner with community institutions to study and develop interventions for older patients. Certainly, to make the largest impact, interventions for geriatric perioperative health need to be things which can be implemented in the community at medium and large sized hospitals. Further, it would be reasonable to study the benefit of centers of excellence in geriatric surgical care, in order to determine which operations can be reasonably performed in the community, and which should be referred.

Much of the data in this paper is consistent with other large studies, for example the proportion of surgery in elderly patients (34%) is similar to that reported by the National Discharge Survey in 2006 (35% of inpatient surgery, 32% of outpatient surgery). This suggests that our findings are robust and that NACOR data accurately represent the surgical experience in the U.S. Regarding the subset which contributed outcomes, our findings are similar to those found by Dr. Li et al, i.e. the oldest group had more than twice the incidence of mortality compared to the young(3). Most importantly, the NACOR dataset has preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative information in a single set which obviates some of the need to link across multiple data sources.

There are limitations to our study and to the NACOR database. In order to check the composition of the NACOR database we compared our data to the American Hospital Association data, which has information regarding all hospitals which performed at least one surgery in the US. We found that NACOR over-represents larger hospitals and under-represents very small and rural facilities. If anything, we have under appreciated the role of community hospitals in our data. In any case, to study smaller hospitals we would need to oversample the small hospitals which contribute to AQI. The outcomes portion of the AQI continues to be under development. Only about 20% of hospitals which contribute to AQI contribute outcomes data, which were mostly large and academic hospitals since they currently have electronic data capture. This means we cannot currently report the association of facility with patient outcomes. Other datasets alone or in combination are currently better equipped to produce more detailed intra- and postoperative information. However, the advantage of AQI is that it includes academic and community hospitals, and includes data on all cases done at a given facility rather than just a sample. In contrast, high fidelity sets like NSQIP contain more in-depth data gleaned from solely academic centers and used a sampling schema. Ghaferi et al provided extremely strong evidence that mortality varies by institution type, therefore the inclusion of community hospitals in outcomes studies is extremely important (27). There are some preoperative and facility factors which cannot be retrieved from this dataset, for example markers of patient-level socioeconomic status or insurance type. This information would have to be linked from practice information or other datasets.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of our study was to describe the pattern of surgery and surgical facilities used by older surgical patients in the United States. We have found that surgery in old people is common, and that in the oldest patients a small number of procedures contribute the largest number of cases. Most importantly, we find that the NACOR database is a viable tool to help understand perioperative risk in elderly patients. We believe this data will be a springboard for future questions including a more in depth look at high risk procedures in the elderly, the need for a geriatric outcomes registry to better appreciate long term outcomes, and further study of the impact of surgical facility size and locations on outcomes in elderly patients. This study underscores the importance of examining outcomes in community centers and highlights that a targeting a few highly represented surgical procedures for quality improvement could have a large impact. Overall, the health of elderly surgical patients is complex and multifactorial; correctly understanding it must be a collaborative process working across disciplines and partnering with community hospitals to study and care for elderly patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding Sources: R01 AG029656 (JHS) and American Geriatrics Society Jahnigen Program (SD) and the Foundation of Anesthesia Education and Research (SD), R03 AG040624(SD), and P50 AG005138 (SD) from National Institute of Health

Sponsor’s Role: none

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Stacie Deiner: Has NIH, FAER, AGS funding, and has served as an expert witness

Benjamin Westlake: works for the ASA AQI

Richard P. Dutton: works for ASA AQI, AQI board, expert witness

Author Contributions:

Stacie Deiner: design, analysis, interpretation, preparation

Benjamin Westlake: acquisition, preparation

Richard P. Dutton: design, analysis, interpretation, preparation

REFERENCES

- 1.The elderly population [Internet].: U.S. Census Bureau. Available from: http://eresources.library.mssm.edu:2114/population/www/pop-profile/elderpop.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;11:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Warner M, Lang BH, et al. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States, 1999–2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:759–765. doi: 10.1097/aln.0b013e31819b5bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung JM, Dzankic S. Relative importance of preoperative health status versus intraoperative factors in predicting postoperative adverse outcomes in geriatric surgical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1080–1085. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garibaldi RA, Britt MR, Coleman ML, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia. Am J Med. 1981;70:677–680. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleisher LA. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. Cardiac risk stratification for noncardiac surgery: Update from the American College of Cardiology/American heart association 2007 guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009 Nov;76(Suppl 4):S9–S15. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s4.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, et al. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung MC, Hamilton K, Sherman R, et al. Impact of teaching facility status and high-volume centers on outcomes for lung cancer resection: An examination of 13,469 surgical patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung MC, Koniaris LG, Yang R, et al. Do all patients with carcinoma of the esophagus benefit from treatment at teaching facilities? J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:18–26. doi: 10.1002/jso.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simunovic M, Rempel E, Theriault ME, et al. Influence of hospital characteristics on operative death and survival of patients after major cancer surgery in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2006;49:251–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sioris T, Sihvo E, Sankila R, et al. Effect of surgical volume and hospital type on outcome in non-small cell lung cancer surgery: A finnish population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kheterpal S, Martin L, Shanks AM, et al. Prediction and outcomes of impossible mask ventilation: A review of 50,000 anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:891–897. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5b87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Ehrenfeld J, et al. The risk and outcomes of epidural hematomas after perioperative and obstetric epidural catheterization: A report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group research consortium. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:1380–1385. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318251daed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mashour GA, Sharifpour M, Freundlich RE, et al. Perioperative metoprolol and risk of stroke after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1340–1346. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318295a25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mashour GA, Stallmer ML, Kheterpal S, et al. Predictors of difficult intubation in patients with cervical spine limitations. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2008;20:110–115. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e318166dd00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myles PS, Leslie K, Peyton P, et al. Nitrous oxide and perioperative cardiac morbidity (ENIGMA-II) trial: Rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2009;157:488,494.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutton RP, Dukatz A. Quality improvement using automated data sources: The anesthesia quality institute. Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;29:439–454. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried TR, Gillick MR, Lipsitz LA. Short-term functional outcomes of long-term care residents with pneumonia treated with and without hospital transfer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society expert panel on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1–E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrison D, Prabhu G, Grieve R, et al. Risk adjustment in neurocritical care (RAIN) - prospective validation of risk prediction models for adult patients with acute traumatic brain injury to use to evaluate the optimum location and comparative costs of neurocritical care: A cohort study. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:1–350. doi: 10.3310/hta17230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madan AK, Aliabadi-Wahle S, Beech DJ. Age bias: A cause of underutilization of breast conservation treatment. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16:29–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(Suppl):166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307:2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1368–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]