Overview

Depression is a significant public health problem for older adults, yet many mistakenly believe that depression is a normal part of aging.1 Reports indicate that 15-27% of older adults in the community2 and up to 37% in primary care settings1 experience depressive symptoms. Subclinical (e.g. non-major) depression is more prevalent in elderly populations than major depressive disorder (MDD). Depression in older adults, often identified as late-life depression (LLD), appears to differ from depression earlier in life, with increased heterogeneity across the adult population. Factors such as age of onset, number of lifetime episodes, somatic symptoms, and comorbidities all may contribute to, or result from psychopathology.3 Rates of depression have risen over the past decade,4 suggesting that future cohorts of older adults will see higher numbers of individuals with depressive disorders.5 As the US population ages, additional efforts will be needed to minimize the burden of depression for older adults and their loved ones.6 Although LLD is associated with a substantial individual and societal burden, it receives much less attention than many medical disorders experienced by older adults.7 Depression has a major impact on the use of medical services, daily functioning, and overall quality of life in later life.8 Given the effects of depression on daily functioning, understanding ways to preserve mental health into late life assumes great importance.6

This article reviews the economic, public health, and caregiver burden of LLD, focusing primarily on the impact of depression, rather than on risk factors for developing depression. However, we present an example of the bidirectional relationship between depression and retirement among older adults to illustrate the complexity that can be associated with trying to disentangle the impact of depression on economic and public health outcomes.

The burden of depression will be assessed from several perspectives, including economic, public health, and the caregiver. Direct costs of depression include costs of depression treatment, as well as treatment for other comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions. Indirect costs of depression include its impact on job functioning, disability, and retirement. In this article, we will consider these direct and indirect costs as the “economic” burden of LLD. Depression can lead to the onset and exacerbation of medical illness and even lead to death, which we will consider the “public health” burden of LLD. Finally, LLD impacts others close to the patient, such as family members and caregivers. We will consider this burden, the “caregiving” burden for depression (which elsewhere has been considered another indirect cost).

Prevalence and patterns of LLD

Nearly five million adults age 65 and older experience LLD,9 and LLD diagnoses have increased over time.10 Yet in clinical practice LLD is often under-recognized and under treated. Primary care physicians appear to be less successful in identifying depression in older people than in younger adults, although there have been few head-to-head studies stratified by age.11

Depression does not develop uniformly over the lifespan. Many analyses compare cross-sectional assessments of depression across age groups rather than longitudinal assessments of depression status,12 although research on LLD trajectories has been increasing.12-20 Recent research has identified several LLD trends of interest. Wu et al found that an age-related increase of depression symptoms occurs entirely through the relationship with medical illness, such as dementia, chronic conditions, and functional limitations. Once these risk factors are controlled, the relationship between age and depressive symptoms becomes non-significant.12 Other studies have found several distinct patterns of LLD depressive symptoms over time, including high or low levels of persistent symptoms,21 or remitting, intermittent, and chronic courses,13 with variations by age and birth cohort.15 These studies demonstrate the variability and diversity in patient experiences of LLD. Continued research into understanding subtypes, trajectories, and patterns of LLD may reveal important targets for future prevention, treatment, and intervention.

Economic burden of LLD

Direct costs

Depression is among the top ten most costly diseases in the US,22 comparable to physical illnesses.23 While some patients may first experience depression in later life, depression typically has an earlier age of onset than other major illnesses, leading to health care costs that accumulate over a long period of time. Depression is the leading cause of psychiatric hospitalizations in older adults.24 It is associated with increased medical burden, health service utilization, longer hospital stays, disability, and more functional impairment than most medical disorders, however, most research is on younger age groups.25 Given that depressed people, particularly older adults, consume health services and medical resources at a rate beyond that which can be explained by their depression alone (e.g. they use more care for other medical disorders), depressed individuals place a substantial burden on societal resources.26-30 Use of medical services by depressed patients exceeds that of similar non-depressed patients by 50%-100%.31-33

Several studies have found variation in health care use based on depression severity. Goldney et al34 found the least use among the non-depressed, moderate use among those with subclinical depression, and the most use among those with MDD. Another study found that total health care costs rose with increasing depression severity.35 An equal or greater burden can be attributed to depressive symptoms; while they are less costly than MDD, their higher prevalence6 results in greater total societal costs.27

Fewer studies have assessed utilization patterns of elderly patients, yet LLD is associated with high utilization in many categories of medical care, not just mental health care, including inappropriate service use.25 Excess costs of depression in community-dwelling elderly are significant even when productivity losses are not considered.36 Depression in geriatric populations can present similarly or exacerbate somatic symptoms associated with comorbid medical conditions,30 which can delay depression treatment.37 Depressed elderly individuals with chronic medical conditions visit the doctor’s office, emergency room,5 and are hospitalized38 more frequently than their non-depressed counterparts.39 Up to 25% of costs of care for medical illnesses may be attributed to depression, and this is clearly associated with longer hospital stays and higher costs.40

Health care costs, like utilization patterns, are significantly greater among older depressed patients.28,41,42 Depressed Medicare enrollees have higher costs in every category of health care except for mental health specialty care.41 Even after initiation of treatment, their health care costs are double that of their non-depressed counterparts.33 Attempts to cut costs by limiting outpatient mental health care may not reduce overall costs, as mental health care comprises only a small proportion of overall health care costs.28,33,43 While some studies have found improved outcomes using targeted interventions for depressed high utilizers,26 there are only a few small studies exploring how costs and utilization following treatment influence outcomes.44

Indirect costs

Not only does depression have a negative impact on overall quality of life, productivity, and earlier life roles (e.g. educational attainment, marital timing and stability, and parental function), but it also has a detrimental impact on late life, such as increased days out of life roles, job loss, and diminished financial success.45 This section will provide a concrete example of the indirect costs of depression, namely the relationship between depression and retirement, where adverse consequences may work in both directions.46 This type of work has previously been conducted in a similar fashion,7,9 examining the complex bidirectional relations between depression and disability,47 as well as depression and self-rated health.48

Example: Bidirectional relationship between depression and retirement

Background and introduction

Social and demographic trends including an aging population, retirement at a younger age, increasing longevity beyond retirement, and an unstable economic climate (potentially leading to involuntary job loss and unplanned earlier or later retirement) highlight the importance of understanding retirement transitions.49-52 Depression negatively affects labor market activity, including at the retirement transition,53-58 is associated with substantial functional impairment,59 and may also be a consequence of retirement transitions.60-63 Given the centrality of retirement transitions in the lives of older adults, coupled with the implications that these changes have on individuals, their families, employers, the health system, and the US government, there is a need for a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic relationship between depression and retirement, and how this relationship may differ across population subgroups. Although some studies suggest that depression may lead to work force exits including retirement,53-55,64 and others indicate that retirement may lead to depression,65-67 no existing research tests whether and to what extent there are reciprocal influences of depression and retirement, and for which groups of people.

Depression can lead to significant functional impairment, and individuals may retire early as a result. Conversely, retirement may lead to feelings of role loss and hence depression. Findings from existing research on the relationship between depression and retirement have produced mixed results. Some studies suggest that workers who become depressed are more likely to retire, and retire earlier than desired or planned.53-55,64 Other studies suggest that once people retire, there is an increased risk of depression,65-67 although other research indicates that retirement may improve emotional well-being,68-70 and that working in old age may be associated with increased depression.71,72 Disentangling these relationships can be complex – if people retire early and become depressed, is the depression a cause or a consequence of the retirement timing and decision, or both, or neither? Furthermore, there are a variety of other factors that may influence depression pre- and post-retirement including age, gender, marital status, race, net worth, physical health, availability of a social support network, other activities including volunteering, and the sense of meaning and identity that an individual attaches to both working and retiring.

Using an autoregressive cross-lagged panel design and a unique, nationally representative, longitudinal dataset of older adults, we examined the potentially bidirectional relationship between depression and retirement over time. This research used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing study that has examined health, wealth, and retirement biennially among adults aged 50 and older since 1992.73

Disciplinary and theoretical perspectives

Economists assume that individuals make decisions based on constrained utility maximization, that is, people seek to maximize their lifetime well-being as much as possible given their personal preferences and budgetary or other limitations.67,74 Individuals trade off consumption during their working lives for consumption in retirement. Consumption in retirement is increased by saving income earned while working, and the amount of the increase depends on the effective savings rate. In theory, people seek to “consumption smooth” across the lifespan such that consumption across the lifespan is relatively consistent even as earned income is typically quite volatile, increasing through one’s careers before abruptly dropping at retirement. When individuals act “rationally” (in the economist’s sense of the word), their optimal retirement age is determined by this forward-thinking process to ensure maximum well-being throughout their lifespan. However, there is increasing evidence that people are generally not fully rational in making decisions about savings and retirement.75 A depressed person may be less able to make optimal decisions about retirement, which may be the case even more so if the illness itself impedes rational decision-making.76,77 Furthermore, mental illness may prevent the realization of the optimal timing of retirement, especially if one needs to leave the workforce early or is unable to return due to depression-related workplace disability. Finally, in a dynamic model over the life course, mental health affects schooling, labor supply, and earnings throughout one’s careers,78-81 indirectly affecting their ability to optimally time retirement and enjoy retired life.

Disablement theory and stress theory may help explain how depression could lead to retirement. The disablement process describes how chronic and acute conditions (such as depression) affect the individual’s functioning, as well as factors that accelerate and slow the retirement process,82,83 potentially necessitating early retirement. In addition, depression may lead to stress, which could negatively affect the immune system response,84,85 potentially leading to work force exits. Therefore, it is important to examine the extent to which disablement and stress associated with depression may influence retirement.

Several sociologically based theories, including role theory,86 life course theory,61,87,88 and continuity theory89 could explain how retirement could lead to depression. If retirement is viewed as a role exit, and a retired person feels an absence of a new role or identity, this could lead to depression. Conversely, retirement could improve quality of life for a person seeking or who is satisfied with this new role. For those who prefer continuity to change, retirement could be seen as a disruption and therefore lead to emotional distress. However, if retirement is planned, or viewed as the fulfillment of a goal, then it could be viewed as positive. Finally, if life transitions are viewed in the context of trajectories, and patterns of employment and retirement are viewed as part of the overall life course, then retirement may be positive. However, if retirement is disruptive or viewed as “not at the right time” then this could lead to depression.

While there is less research and theory supporting a simultaneous influence of depression and retirement on one another, it is important to explore all possibilities, including the notion of feedback loops and reciprocal pathways. This type of immediate feedback loop may be more apparent when examining depression and physical comorbidities,48 but it is likely that with respect to work force status changes, a time lag of some duration is needed to see how mental health and retirement choices affect one another. Further, comprehensively exploring all possible options for relationships between depression and retirement represents an advance over existing studies.

Methods

Study sample

We used HRS data for this study.73 The HRS is a longitudinal study of a nationally representative cohort of older Americans that was designed to assess the predictors and consequences of transitions out of the workforce in later life. HRS respondents in our analyses met the following criteria: 1) they were born between 1900 and 1947, 2) they were either working or retired in each biennial study wave between 1998 and 2006 (five total study waves), and 3) they did not have any missing data on any study covariates.

Study measures

Depression

Depressive symptom status was measured using the eight-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D8) to measure depressive symptoms.90 The CES-D has been widely used in studies of late life depression and has good psychometric properties for use in these populations. To determine depressive symptoms, each self-respondent was asked the following questions with response options of “yes” or “no”: 1) Much of the time during the past week, I felt depressed; 2) I felt everything I did was an effort; 3) My sleep was restless; 4) I was happy; 5) I felt lonely; 6) I enjoyed life; 7) I felt sad; 8) I could not “get going.” For each respondent, the total number of “yes” responses to questions 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8 and the “no” responses to questions 4 and 6 were summed to arrive at a total depressive symptom score ranging from 0 to 8. We classified those who reported four or more depressive symptoms as having significant depressive symptoms, a cutoff that has been found to produce comparable results to the 16-symptom cutoff for the well-validated 20-item CES-D scale.91 Given that the CES-D has a well-established second order factor structure,48,92 we created three separate additive-composite indicators for the present study by summing the responses to the items comprising each dimension (i.e., items 1, 6, and 7 for depressive affect, items 2, 3, and 8 for somatic complaints, and items 4 and 6 for positive affect).

Retirement

We used a single binary indicator of employment status for this study, based on an indicator of labor force status.93 If the respondent claimed to be working full or part time, the respondent was considered to be “working.” If the respondent claimed to be partially or fully retired, the respondent was considered to be “retired.” Respondents who claimed to be disabled, unemployed, or not in the labor force were not included.

Covariates

We included gender, marital status (married/partnered, divorced/separated, widowed, never married), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, other), and level of education (less than high school, high school graduate, more than high school) as categorical independent variables. We included mean age, a count of chronic health conditions (range 0-7), self-assessed health (range 1-5, poor, fair, good, very good, excellent), functional impairment (range 0-5, none to high), and total household net worth as continuous independent variables in the analyses. The seven possible chronic conditions included: 1) high blood pressure or hypertension; 2) diabetes or high blood sugar; 3) cancer or a malignant tumor of any kind except skin cancer; 4) chronic lung disease except asthma such as chronic bronchitis or emphysema; 5) heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems; 6) stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA); and 7) arthritis or rheumatism. (These characteristics are presented in Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics at 1998 of the HRS cohort sample (n = 8,163).

| Characteristic | Sample % |

|---|---|

| Gender: Female | 51.4 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/Partnered | 72.4 |

| Divorced/Separated | 10.9 |

| Widowed | 13.8 |

| Never Married | 3.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 82.0 |

| Black | 11.8 |

| Hispanic | 4.6 |

| Other | 1.6 |

| Education | |

| Less than High School | 18.9 |

| High School Graduate | 34.9 |

| More than High School | 46.3 |

| Sample Mean (S.D.) | |

| Age (years) | 63.8 (8.3) |

| Number of Chronic Health Conditions (0-7) | 1.3 (1.1) |

| Self-Assessed Health (1 = poor to 5 = excellent) | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Functional Impairment (0 = none to 5 = high) | 0.1 (0.5) |

| Total Net Worth of Assets | 362,193 (754,523) |

Note: sample includes those alive throughout 1998-2006, whose work status was either working or retired at all waves 1998-2006, who did not have any waves of data that were collected by proxy report, and who were born between 1900 and 1947. This included 8,175 individuals, of whom 12 were missing data on other covariates.

Statistical analyses

We evaluated the reciprocal relationship between depression and retirement by using an autoregressive cross-lagged panel design with five waves of data. We concurrently tested three sets of possible relationships: 1) depression leads to retirement, 2) retirement leads to depression, and 3) depression and retirement occur simultaneously. We represented depression and retirement as 10 latent variables: depressive symptomatology (waves 1–5) and retirement (waves 1–5). Each latent variable at time (t+1) is a function of seven components: first, an autoregression representing the effect of the same variable at the previous time (i.e., a “stability coefficient”); second, the cross-lagged effect of the other latent variable at the previous time; third, a set of time invariant covariates whose regression parameters are allowed to vary across time; fourth, a disturbance for each latent variable that is allowed to correlate with the disturbance for the other latent variable contemporaneously (i.e., within the same wave); fifth, three indicators for the depression latent variable (depressive affect, somatic complaints, positive affect), with a given indicator’s unstandardized factor loading constrained to be equal across waves; sixth, a single indicator for retirement, with the standardized factor loading set at 1.0 (and thus constrained to be equal across waves); and seventh, an error term for each manifest indicator of the depression latent construct that is allowed to covary with itself across the immediately prior and subsequent wave (i.e., auto-correlated measurement errors). The equality constraints on the measurement model (i.e., equal factor loadings across waves) comprise an essential assumption that, if not met, precludes testing other parameters in the model.94 We estimated model parameters by using maximum likelihood estimation. We used only Wave 1 values of the covariates in an attempt to reduce the complexity of the model.

Results

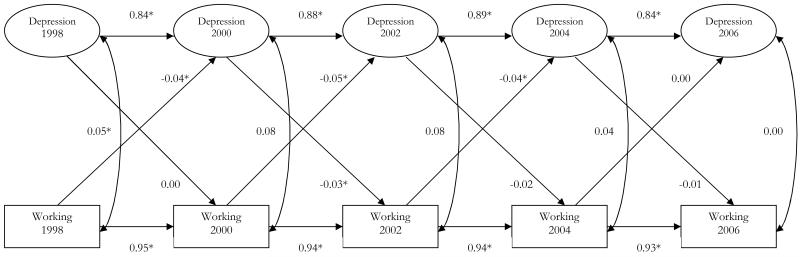

We had several notable findings among the 8,163 individuals who were either working or retired during the study period (Figure 1). We found a significant concurrent relationship between depression and employment status only at the first wave. This indicated that time lags were needed to help explain the bidirectional relationship between depression and retirement. Second, we found that people who were working compared to retired were significantly less likely to be depressed at the subsequent wave (found in three of four instances). Finally, we found that depression lead people to be more likely to be retired than working, but this finding was only significant in one of four instances.

Figure 1. Standardized estimated of the bidirectional relationship between depression and working (vs. retirement).

Notes: * p ≤ 0.05. Estimates for the relationship of 1998 characteristics are not presented, in the interest of simplicity.

Fully cross-lagged model: χ2 = 5419.48, degrees of freedom (df) = 226, p<0.0001

Fit Statistics: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.840, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.916, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.053

Our findings also included relations with covariates primarily in expected directions. Women, black and Hispanic respondents, those with more comorbid health conditions, ADL limitations, and worse self-assessed health were more likely to be depressed. Those who were more educated, older, married, and of higher net worth were less likely to be depressed. Those with the highest education levels and who were widowed were more likely to be working than retired. Those who were black, older, those with more health conditions and ADL limitations, worse self-assessed health, and higher net worth were less likely to be working than retired. Women, those of other race or Hispanic, and those who were separated or never married were no more likely to be working than retired.

Our analyses had several advantages over prior work, as previous studies typically use cross sectional analyses, small samples, only focus on one of these relationships, use non-representative samples, and use weak measures of mental health or employment status.

Implications of example for research and practice

A key finding from this research is that there is a higher likelihood of depression associated with being retired, relative to continuing to work. Further, there was also some evidence that depression may be associated with movement from working status to retirement in the subsequent wave. This research is significant because of the important sociodemographic shifts currently occurring in the US society, including an aging population and reductions in labor force growth, an increasing retirement age, pending insolvency of the Social Security system, and medical advances leading to longer life expectancy and declines in physical impairments.50 In this context, the impact of mental health on quality of life and economic outcomes both pre- and post-retirement may be growing. This research explicitly examined in a longitudinal context how depression and retirement are related. Examining these relationships in a longitudinal, nationally-representative sample is a necessary step in determining how best to assist those most at risk for potential negative health and employment outcomes.

Public health burden of LLD

LLD represents a substantial public health burden for older adults,95 an increasing concern due to the quickly expanding population of elderly in the US.9 While a comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this paper, the negative impact that depression has on a wide range of medical conditions and physical impairments is well-established.45,46,96 The presence of depressive disorders often adversely affects the onset,97 course, and treatment of other chronic diseases.98,99 Depressed older adults may have multiple complaints.100 Further, depression may also be associated with unhealthy behaviors and lifestyle choices that exacerbate medical disorders and physical impairments. Therefore, the importance of assessing patients with chronic medical illnesses cannot be overemphasized.101

In addition to its impact on physical health, LLD increases the risk of disability,102 defined as restricting one’s ability to perform one’s normal activities due to impairment, and mortality. Depression stands apart as the mental disorder claiming the highest percentage of “disability-adjusted life years” or DALYs. Furthermore, analogous to the presence of various patterns of depressive symptoms (as discussed earlier), depressive symptoms may lead to a variety of patterns of disability over time.103 Depression is also the mental disorder with the highest increased risk of all-cause mortality104 and is associated with both all-cause and cause-specific mortality.105 Finally, LLD has also been shown to decrease active life expectancy.106

The “depression-mortality hypothesis” predicts that depressed people are likely to die sooner than the non-depressed.107 It suggests that depression and other health conditions indirectly influence one another leading to a “cascade to death.”107 Critics argue that excess natural death (e.g. higher rate of mortality beyond what would be expected) in the depressed is due to complicating physical illness or poor health behaviors associated with depression rather than depression itself, and that excess deaths are from unnatural causes (i.e. suicide).108 Research suggests that neither suicide, nor physical illness, nor poor health alone can explain excess mortality among depressed people. Depressive syndromes are associated with significant functional impairment, disability, and suicide. While most research on depression and mortality has been done in clinical populations,109 a review of community studies of depression and mortality in older adults found that diagnosed depression was associated with increased mortality.110 Another recent study also found increased risk of death among older primary care patients with depression.111

Caregiver burden of LLD

The negative consequences of LLD, including reduced energy, functioning, and motivation, lead to problems living independently, and result in an increased need for unpaid caregiving from friends and family members, or informal caregiving.112 Informal caregiving contributes to the burden of LLD in a several ways. As of 2006, it was estimated that 34 million people provided informal caregiving, the largest source of long-term care in the United States, valued at over $350 billion annually.112-114 Caregivers may risk the loss of income, health insurance, and other benefits by giving up or reducing their work hours in order to provide care for depressed loved ones.112 One study found that depressed elders receive up to three additional hours of informal care weekly compared to those without depression, representing a yearly cost of $1,330 per person, for a total of over $9 billion nationwide.115 This burden encompasses both the value of the care provided and the adverse psychological and physical effects that caregiving has on the informal caregivers themselves.114,116,117

Evidence suggests that there are long-term negative health effects and increased mortality risks for those caring for depressed older adults, and that caregivers themselves are also likely to suffer from depression.118 The emotional and physical toll that informal caregiving has on the caregivers also affects caregiver family and social network functioning, and leads to poorer outcomes and disease trajectories as well as increased use of health care services.112,119-121 Literature documents the impact affective disorders have on those in the depressed individual’s life, especially spouses and partners, family caregivers, and young children who may reside in the household.113,119,122,123 Recent research suggests that caring for someone with depression is no less burdensome than caring for someone with a schizoaffective disorder or dementia.121 Additionally, it is possible that there is a mutually reinforcing interaction between caregiver burden and depression and poor outcomes in their care recipient.

Many caregivers report distress. Up to 80% of caregivers endorse issues or treatment for complaints such as sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, tension, or fatigue.119 A high caregiving burden can result in reductions in social or familial support,119,120 leading to increased vulnerability. However, treatment of LLD may mitigate these effects on caregivers and lower overall disease burden.117

For young children who reside in the same household as older adults with depression, the impact may be profound. Over time, exposure to a nearby adult with LLD can lead to behavior difficulties, sleep disturbances, school-based problems, attention-deficits, and stunting of social development.119 Problems that occur in the early stages of life have consequences that can extend beyond the families and individuals touched directly. These issues also affect the health care and welfare systems of the nation over the long term, as childhood-based disturbances may be linked to outcomes ranging from health and well-being to delinquent behavior and lower socioeconomic success.

If we hope to improve the functioning and quality of life of vulnerable older adults suffering from LLD, we must consider the context of these individuals. Poor prognosis for individuals is intimately tied to their social support networks, and when that support is burdened or impaired, it results in poorer outcomes across the network. The economic burden of LLD is substantial even before considering its long-term impact on the families, children, and caregivers. To improve LLD outcomes, we must support interventions that look beyond the depressed individual, and include partners, friends, children, and other members of that individual’s social network.117

Future directions

Treatment

Since effective treatments for LLD are available,124 receiving proper depression care could be beneficial not only for the individual, but for society as well.36 Treatment may improve depression outcomes in older adults125,126 as well as physical functioning.127,128 Treatments for LLD decrease depression-related costs as well as benefitting patients. For example, an intervention of targeted mental health treatment and care coordination reduced costs by accelerating transitions from inpatient to outpatient care, resulting in increased outpatient costs, but nearly tripled savings in inpatient costs.129 Although there is substantial evidence documenting the relationship between depression and mortality, there is relatively limited data on how depression treatment might mitigate this effect. Several studies have found that depression treatment and care management decreases mortality,130,131 while another study indicated that treatment improves prognosis in community dwelling elderly.132 Given this promising evidence that treatment may improve outcomes, it may justify increased efforts to prevent, detect, and treat depression.109 Furthermore, properly addressing the substantial emotional, health, and potential financial needs of depressed older adults could improve quality of life and well-being for these individuals.

Although rates of LLD diagnoses and treatment, particularly with antidepressant medications,10 have increased over time, many barriers to optimal treatment remain. Depression diagnoses and antidepressant treatment have increased for a variety of reasons, including changes in cultural attitudes, reimbursement practices, and healthcare delivery.10 Attributing depression to old age may be a barrier to treatment seeking,133 and there are many potential reasons for poor treatment adherence in older adults, including stigma, negative patient beliefs about treatment, physical and psychiatric comorbidity, and costs of care.134 Given that many older patients may prefer psychotherapy over antidepressants,135 focusing primarily on antidepressants alone represents suboptimal care for LLD. Expanding the availability of promising psychosocial interventions for LLD could be beneficial for patients, caregivers, and society.10

Genetics

Another promising area for future research is on genetic contributions to LLD. Genetic explanations, such as gene-environment interactions may help explain why some individuals become depressed after life changes and others do not.136 There is debate in the literature regarding the importance of genetic factors on LLD. One explanation suggests that genes may have a less important role in LLD than they do in earlier or childhood onset depression, positing a more important biological role such as vascular explanations for LLD.9 An alternative argument suggests that many of the psychosocial factors contributing to earlier life depression such as family of origin conflicts will have a less important role in later life, leaving a more important role for genetics in the management of mood over the lifespan. Given the limited focus on genetics of LLD (as compared to earlier onset depression),137 there is substantial room for additional study of both the genetic contributors to LLD, as well as the gene-environment interactions that may lead to either vulnerability or resilience to LLD, which may be related to issues such as loss of independence, spouse or family members, and increased medical illness. However, it is important to remember that while genetic explanations may be attractive, research indicates that environmental factors explain at least as much of the variance in depression as genes do.138

Summary

This paper highlighted the multiple burdens of LLD on patients, caregivers, and society. Basic, clinical, epidemiological, and health services research should focus more resources and attention on this devastating and costly yet treatable illness.

Synopsis: This article reviews the burden of late-life depression (LLD) from several perspectives, including costs of depression treatment and treatment for other comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions; the impact of LLD on job functioning, disability, and retirement; and how LLD influences others, such as family members and caregivers.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA IIR 10-176-3; Dr. Zivin) and the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Services (CD2 07-206-1; Dr. Zivin). Drs. Wharton and Rostant were funded by a National Institute of Mental Health T32 Geriatric Mental Health Services fellowship. The authors would like to acknowledge Amy S. B. Bohnert, PhD, and Erin M. Miller, MS for their contributions to earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding support and disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging . Older adults and mental health issues and opportunities. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulsant BH, Ganguli M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of depression in late life. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hybels CF, Pieper CF. Epidemiology and Geriatric Psychiatry. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17(8):627–631. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad2ba8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Changes in the prevalence of major depression and comorbid substance use disorders in the United States between 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman DP, Perry GS. Depression as a major component of public health for older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatric Services. 1999 Sep;50(9):1158–1166. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine . The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, Akincigil A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(12):1718–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer JL. Managing depression in geriatric populations. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007 Oct-Dec;19(4):221–238. doi: 10.1080/10401230701653245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akincigil A, Olfson M, Walkup JT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in older community-dwelling adults: 1992-2005. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2011 Jun;59(6):1042–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell AJ, Rao S, Vaze A. Do Primary Care Physicians Have Particular Difficulty Identifying Late-Life Depression? A Meta-Analysis Stratified by Age. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2010;79(5):285–294. doi: 10.1159/000318295. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Schimmele CM, Chappell NL. Aging and Late-Life Depression. Journal of Aging and Health. 2012 Feb 1;24(1):3–28. doi: 10.1177/0898264311422599. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luppa M, Luck T, Konig HH, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Natural course of depressive symptoms in late life. An 8-year population-based prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders. Jul 25;2012:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.009. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang J, Xu X, Quinones AR, Bennett JM, Ye W. Multiple trajectories of depressive symptoms in middle and late life: Racial/ethnic variations. Psychology and Aging. 2011 Aug 29; doi: 10.1037/a0023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y. Is old age depressing? Growth trajectories and cohort variations in late-life depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007 Mar;48(1):16–32. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GG, Hybels CF, Blazer DG. Trajectory classes of depressive symptoms in a community sample of older adults. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012 Jun;125(6):492–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byers A, E V, L L, et al. Twenty-year depressive trajectories among older women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1073–1079. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Pieper CF, Landerman LR, Steffens DC. Profiles of Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults Diagnosed With Major Depression: Latent Cluster Analysis. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009 May;17(5):387–396. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hybels CF, Pieper CF, Blazer DG, Steffens DC. The course of depressive symptoms in older adults with comorbid major depression and dysthymia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008 Apr;16(4):300–309. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f15f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreescu C, Chang C, Mulsant B, Ganguli M. Twelve-year depressive symptom trajectories and their predictors in a community sample of older adults. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(2):221–236. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207006667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Reynolds CF, Cary MS, Bruce ML. Prognostic factors, course, and outcome of depression among older primary care patients: The PROSPECT study. Aging & Mental Health. 2012;12(4):452–461. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.638904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall RC, Wise MG. The clinical and financial burden of mood disorders. Cost and outcome. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(2):S11–18. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J, Batelaan N, de Graaf R, Beekman A. Costs of nine common mental disorders: implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2006 Dec;9(4):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists ASHP therapeutic position statement on the recognition and treatment of depression in older adults: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 1998 Dec 1;55(23):2514–2518. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/55.23.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, de Beurs E, Geerling SW, van Tilburg W. The impact of depression on the well-being, disability and use of services in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002 Jan;105(1):20–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.10078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(4):345–351. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267(11):1478–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997;277(20):1618–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440052032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Distressed high utilizers of medical care. DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1990;12(6):355–362. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, et al. Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(2):169–176. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):352–357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manning WG, Jr., Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):541–553. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(10):850–856. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Dal Grande E, Taylor AW. Subsyndromal depression: prevalence, use of health services and quality of life in an Australian population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004 Apr;39(4):293–298. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Patterns of health care costs associated with depression and substance abuse in a national sample. Psychiatric Services. 1999 Feb;50(2):214–218. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasiliadis HM, Dionne PA, Preville M, Gentil L, Berbiche D, Latimer E. The Excess Healthcare Costs Associated With Depression and Anxiety in Elderly Living in the Community. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012 Apr 10;:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.016. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klinkman MS. Competing demands in psychosocial care. A model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1997;19(2):98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang BY, Cornoni-Huntley J, Hays JC, Huntley RR, Galanos AN, Blazer DG. Impact of depressive symptoms on hospitalization risk in community-dwelling elder persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(10):1279–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, Anderson GF, Cooper LA. Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Medical Care. 2004;42(6):512–521. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000127998.89246.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levenson JL, Hamer RM, Rossiter LF. Relation of psychopathology in general medical inpatients to use and cost of services. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(11):1498–1503. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Katon WJ, et al. Healthcare Costs Associated with Depression in Medically Ill Fee-for-Service Medicare Participants. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(3):506–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unutzer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;60(9):897–903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, Smith J, Smith GR., Jr. Expenditures for the treatment of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):883–888. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Henk HJ. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatric Services. 1997 Jan;48(1):59–64. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler RC. The Costs of Depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012 Mar;35(1):1–+. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unutzer J, Park M. Public Health Burden of Late-Life Mood Disorders. In: Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds CF 3rd, editors. Late-Life Mood Disorders. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen CM, Mullan J, Su YY, Griffiths D, Kreis IA, Chiu HC. The Longitudinal Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Disability for Older Adults: A Population-Based Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2012 doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls074. epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kosloski K, Stull DE, Kercher K, Van Dussen DJ. Longitudinal analysis of the reciprocal effects of self-assessed global health and depressive symptoms. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005 Nov;60(6):P296–P303. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.p296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gendell M. Retirement age declines again in 1990s. Monthly Labor Review. 2001;124(10):12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mermin GBT, Johnson RW, Murphy DP. Why do boomers plan to work longer? Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007 Sep;62(5):S286–S294. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.5.s286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feldman DC. The Decision to Retire Early: A Review and Conceptualization. Academy of Management Review. 1994 Apr;19(2):285–311. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayward MD, Grady WR, McLaughlin SD. Changes in the retirement process among older men in the United States: 1972-1980. Demography. 1988 Aug;25(3):371–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conti RM, Berndt ER, Frank RG. Early retirement and public disability insurance applications exploring the impact of depression. Cambridge, MA: May, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doshi JA, Cen L, Polsky D. Depression and retirement in late middle-aged U.S. workers. Health Services Research. 2008 Apr;43(2):693–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karpansalo M, Kauhanen J, Lakka TA, Manninen P, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Depression and early retirement: prospective population based study in middle aged men. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005 Jan;59(1):70–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.010702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wray LA. Mental Health and Labor Force Exits in Older Workers The Mediating or Moderating Roles of Physical Health and Job Factors. : University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: Jun, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waghorn G, Chant D. Receiving treatment and labor force activity in a community survey of people with anxiety and affective disorders. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2007 Dec;17(4):623–640. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marcotte DE, Wilcox-Gok V, Redmon PD. Prevalence and patterns of major depressive disorder in the United States labor force. Journal of Mental Heatlh Policy and Economics. 1999 Sep 1;2(3):123–131. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199909)2:3<123::aid-mhp55>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, Beekman AT, Guralnik JM. Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000 Dec;61(1-2):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christ SL, Lee DJ, Fleming LE, et al. Employment and occupation effects on depressive symptoms in older Americans: does working past age 65 protect against depression? Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007 Nov;62(6):S399–403. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.s399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JE, Moen P. Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: a life-course, ecological model. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002 May;57(3):P212–222. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szinovacz ME, Davey A. Retirement transitions and spouse disability: effects on depressive symptoms. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004 Nov;59(6):S333–342. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.s333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindeboom M, Portrait F, van den Berg GJ. An econometric analysis of the mental-health effects of major events in the life of older individuals. Health Economics. 2002 Sep;11(6):505–520. doi: 10.1002/hec.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sobocki P, Lekander I, Borgstrom F, Strom O, Runeson B. The economic burden of depression in Sweden from 1997 to 2005. European Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;22(3):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Butterworth P, Gill SC, Rodgers B, Anstey KJ, Villamil E, Melzer D. Retirement and mental health: analysis of the Australian national survey of mental health and well-being. Social Science and Medicine. 2006 Mar;62(5):1179–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buxton JW, Singleton N, Melzer D. The mental health of early retirees--national interview survey in Britain. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005 Feb;40(2):99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0866-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Charles KK. Is retirement depressing - labor force inactivity and psychological well-being in later life. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: Jul, 2002. p. 9033. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drentea P. Retirement and mental health. Journal of Aging and Health. 2002 May;14(2):167–194. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Midanik LT, Soghikian K, Ransom LJ, Tekawa IS. The effect of retirement on mental health and health behaviors: the Kaiser Permanente Retirement Study. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995 Jan;50(1):S59–S61. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reitzes DC, Mutran EJ, Fernandez ME. Does retirement hurt well-being? Factors influencing self-esteem and depression among retirees and workers. Gerontologist. 1996 Oct;36(5):649–656. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi NG, Bohman TM. Predicting the changes in depressive symptomatology in later life: how much do changes in health status, marital and caregiving status, work and volunteering, and health-related behaviors contribute? Journal of Aging and Health. 2007 Feb;19(1):152–177. doi: 10.1177/0898264306297602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mein G. Is retirement good or bad for mental and physical health functioning? Whitehall II longitudinal study of civil servants. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(1):46–49. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Juster FT, Suzman R. An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30(Supplement):S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raymo JM, Sweeney MM. Work-family conflict and retirement preferences. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(3):S161–S169. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi J, Laibson D, Madrian B, Metrick A. Saving for retirement on the path of least resistance. Rodney L. White Center for Financial Research, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Frank R, McGuire T. Economics and Mental Health. In: Culyer A, Newhouse J, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol. 1. Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frank RG. Behavioral economics and health economics. Cambridge, MA: Jul, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ettner SL, Frank RG, Kessler RC. The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 1997 Oct;51(1):64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Timbie JW, Horvitz-Lennon M, Frank RG, Normand SL. A meta-analysis of labor supply effects of interventions for major depressive disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2006 Feb;57(2):212–218. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kessler RC, Frank RG. The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(4):861–873. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al. Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Affairs. 1999;18(5):163–171. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Van Gool CH, Kempen GI, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, van Eijk JT. Impact of depression on disablement in late middle aged and older persons: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Social Science and Medicine. 2005 Jan;60(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002 Oct;53(4):873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:83–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.George LK. Sociological perspectives on life transitions. Annual Review of Sociology. 1993;19:353–373. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Han SK, Moen P. Work and family over time: A life course approach. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999;562:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Szinovacz ME, Davey A. Honeymoons and joint lunches: effects of retirement and spouse’s employment on depressive symptoms. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004 Sep;59(5):P233–245. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.p233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quick HE, Moen P. Gender, employment, and retirement quality: a life course approach to the differential experiences of men and women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;3(1):44–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Steffick DE. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R. Measurement Properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in Older Populations. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;2(1):64–62. [Google Scholar]

- 93.St. Clair P, Blake D, Bugliari D, et al. RAND HRS Data Documentation, Version H. Labor & Population Program, RAND Center for the Study of Aging; Santa Monica, CA: Feb, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ferrer E, McArdle JJ. Alternative structural models for multivariate longitudinal data analysis. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal. 2003;10(4):493–524. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278(14):1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karakus MC, Patton LC. Depression and the onset of chronic illness in older adults: a 12-year prospective study. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2011 Jul;38(3):373–382. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The Vital Link Between Chronic Disease and Depressive Disorders. Preventing chronic disease. 2005;2(1):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease. The Harvard School of Public Health; Boston, MA: 1996. Global Burden of Disease and Injury Series. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Drayer RA, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ, et al. Somatic symptoms of depression in elderly patients with medical comorbidities. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;20(10):973–982. doi: 10.1002/gps.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cyr NC. Depression and older adults. Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal. 2007 Feb;85(2):397–401. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(07)60050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carriere I, Gutierrez LA, Peres K, et al. Late life depression and incident activity limitations: Influence of gender and symptom severity. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011 Sep;133(1-2):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hybels CF, Pieper CF, Blazer DG, Fillenbaum GG, Steffens DC. Trajectories of mobility and IADL function in older patients diagnosed with major depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;25(1):74–81. doi: 10.1002/gps.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eaton WW, Martins SS, Nestadt G, Bienvenu OJ, Clarke D, Alexandre P. The Burden of Mental Disorders. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008 Nov 1;30(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lin EHB, Heckbert SR, Rutter CM, et al. Depression and increased mortality in diabetes: unexpected causes of death. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(5):414–421. doi: 10.1370/afm.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reynolds SL, Haley WE, Kozlenko N. The impact of depressive symptoms and chronic diseases on active life expectancy in older Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(5):425–432. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff32e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schulz R, Martire LM, Beach SR, Scheier MF. Depression and Mortality in the Elderly. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(6):204–208. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Black DW, Winokur G, Nasrallah A. Is death from natural causes still excessive in psychiatric patients-A follow up of 1593 patients with major-affective disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175(11):674–680. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cole MG. Does depression in older medical inpatients predict mortality? A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.002. 2007/10// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saz P, Dewey ME. Depression, depressive symptoms and mortality in persons aged 65 and over living in the community: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(6):622–630. doi: 10.1002/gps.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Reynolds CFI, Cary MS, Bruce ML. Course of Depression and Mortality Among Older Primary Care Patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psych. 2012;20(10):895–903. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182331104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Verma K, Silverman BC. Economic Burden of Late-Life Depression: Cost of Illness, Cost of Treatment, and Cost Control Policies. In: Ellison JM, Kyomen HH, Verma S, editors. Mood disorders in later life. Informa Healthcare; New York: 2009. pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Family Caregiver Alliance . Fact sheet: Selected caregiver statistics. San Francisco, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Clark MC, Diamond PM. Depression in Family Caregivers of Elders: A Theoretical Model of Caregiver Burden, Sociotropy, and Autonomy. Res Nurs Health. 2010 Feb;33(1):20–34. doi: 10.1002/nur.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Langa KM, Valenstein MA, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MU, Vijan S. Extent and cost of informal caregiving for older Americans with symptoms of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004 May;161(5):857–863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003 Jun;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Martire LM, Schulz R, Reynolds CF, Karp JF, Gildengers AG, Whyte EM. Treatment of Late-Life Depression Alleviates Caregiver Burden. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010 Jan;58(1):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Thompson A, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Katon W. One extra month of depression: the effects of caregiving on depression outcomes in the IMPACT trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008 May;23(5):511–516. doi: 10.1002/gps.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Van Wijngaarden B, Schene AH, Koeter MW. Family caregiving in depression: impact on caregivers’ daily life, distress, and help seeking. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004 Sep;81(3):211–222. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang JK, Zhao XD. Family functioning and social support for older patients with depression in an urban area of Shanghai, China. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2012 Nov-Dec;55(3):574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rane LJ, Fekadu A, Papadopoulos AS, et al. Psychological and physiological effects of caring for patients with treatment-resistant depression. Psychological Medicine. 2012 Sep;42(9):1825–1833. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alzheimer’s Association . 2012 Facts and Figures Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 123.National Family Caregivers Association . Caregiver Survey-2000. National Family Caregivers Association (NFCA); Kensington, MD: Oct, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smit F. Psychological treatment of late-life depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;21(12):1139–1149. doi: 10.1002/gps.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Harpole LH, Williams JW, Jr., Olsen MK, et al. Improving depression outcomes in older adults with comorbid medical illness. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005 Jan-Feb;27(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS. The Treatment Initiation Program: an intervention to improve depression outcomes in older adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005 Jan;162(1):184–186. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Callahan CM, Kroenke K, Counsell SR, et al. Treatment of depression improves physical functioning in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005 Mar;53(3):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kominski G, Andersen R, Bastani R, et al. UPBEAT: the impact of a psychogeriatric intervention in VA medical centers. Unified Psychogeriatric Biopsychosocial Evaluation and Treatment. Medical Care. 2001 May;39(5):500–512. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200105000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Avery D, Winokur G. Mortality in depressed patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy and antidepressants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33(9):1029–1037. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Lin JY, Bruce ML. The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults - A Randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146(10):689–698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Denihan A, Kirby M, Bruce I, Cunningham C, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Three-year prognosis of depression in the community-dwelling elderly. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:453–457. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sarkisian CA, Lee-Henderson MH, Mangione CM. Do depressed older adults who attribute depression to “old age” believe it is important to seek care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003 Dec;18(12):1001–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zivin K, Kales HC. Adherence to depression treatment in older adults: a narrative review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(7):559–571. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Apr;51(4):505–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Monroe SM, Reid MW. Life Stress and Major Depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009 Apr;18(2):68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim J-M, Stewart R, Kim S-W, et al. Interactions between life stressors and susceptibility genes (5-HTTLPR and BDNF) on depression in Korean elders. Biological Psychiatry. 2007 Sep 1;62(5):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tennant C. Life events, stress and depression: a review of recent findings. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2002 Apr;36(2):173–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]