Abstract

Therizinosaurs are a group of herbivorous theropod dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of North America and Asia, best known for their iconically large and elongate manual claws. However, among Therizinosauria, ungual morphology is highly variable, reflecting a general trend found in derived theropod dinosaurs (Maniraptoriformes). A combined approach of shape analysis to characterize changes in manual ungual morphology across theropods and finite-element analysis to assess the biomechanical properties of different ungual shapes in therizinosaurs reveals a functional diversity related to ungual morphology. While some therizinosaur taxa used their claws in a generalist fashion, other taxa were functionally adapted to use the claws as grasping hooks during foraging. Results further indicate that maniraptoriform dinosaurs deviated from the plesiomorphic theropod ungual morphology resulting in increased functional diversity. This trend parallels modifications of the cranial skeleton in derived theropods in response to dietary adaptation, suggesting that dietary diversification was a major driver for morphological and functional disparity in theropod evolution.

Keywords: Theropoda, shape analysis, finite-element analysis, functional morphology

1. Introduction

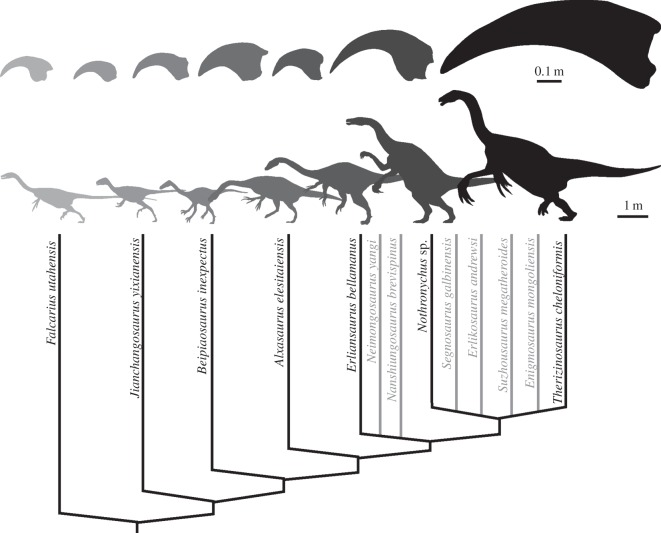

Therizinosauria is a group of enigmatic theropod dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Although they exhibit an unusual suite of anatomical features in the cranial and postcranial skeleton [1], they are best known for the presence of exceptionally enlarged and elongate claws on the forelimbs. This reaches its extremes in the eponymous species Therizinosaurus cheloniformes, which possessed manual unguals of over 50 cm in length [2]. While Therizinosaurus might represent a singular case of hypertrophied specialization, a general trend towards an increase in size and the lengthening of the unguals exists in Therizinosauria [3]. Across the clade, however, the manual unguals show a large morphological, and thus presumably also functional, diversity (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Manual unguals of Therizinosauria shown in lateral outline illustrating the large morphological variability across the group. Phylogeny based on the study of Zanno [4].

Many of the anatomical characteristics and skeletal specializations in the therizinosaurian bauplan, such as a row of small, lanceolate teeth, the presence of a rostral rhamphotheca, an elongate neck and a broad, opisthopubic pelvis, have been explained as a result of the shift in dietary preferences from carnivory to herbivory [5–7]. The function of the enlarged manual unguals, however, has been the focus of numerous speculative arguments. Many hypotheses exist about their biological role, suggesting therizinosaurs used their claws to gather food by digging into the colonies of social insects [8], stripping bark off trees [9] or harvesting and raking vegetation [10], likening them to extant ant-eaters or the extinct giant ground sloth Megatherium. This idea is also reflected in the selection of taxon names, such as Suzhousaurus megatherioides [11] or Nothronychus (‘sloth claw’) [12]. Further functions, involving climbing [13] or sexual display [3] have been discussed, but without consensus.

In the past, numerous studies have focused on the morphology and geometry of pedal unguals in theropod dinosaurs [14,15], supplemented with or based on observations in extant birds [16,17] or squamates [18], in an attempt to infer function and behaviour from morphology. The manual unguals of theropod dinosaurs in general, and therizinosaurs in particular, however, have rarely been considered, or have been limited to range-of-motion studies of the forelimbs [19–21]. This is surprising, as in bipedal animals, the manual unguals are not restricted by locomotory constraints. It can thus be assumed that the morphology of the manual unguals would more justifiably reflect their specific, locomotor-independent function.

In this study, two-dimensional shape analysis based on fast Fourier transformation (FFT) is used to characterize the morphological variability of manual unguals in theropod dinosaurs. The morphospace positions of the various taxa are compared with those of extant mammals, for which claw function is more readily available, to elucidate claw usage in theropods in general and in therizinosaurs in particular. Using three-dimensional finite-element analysis (FEA), the biomechanical performance of the manual unguals of five different therizinosaurian taxa is investigated by simulating different functional scenarios, thereby testing the hypothesis that the unguals in therizinosaurs were adapted to specific functions.

2. Material and methods

(a). Shape analysis

For the shape analysis, the manual unguals of 65 theropod species were sampled. For the functional comparison, 40 extant and six extinct mammalian species were sampled (see the electronic supplementary material, SI for complete taxon list). Specimens were selected for study based on first-hand observations of museum collections and a detailed survey of the primary literature. Specimens were selected according to their completeness and availability. Contours of the individual manual unguals were manually traced in lateral view, subsequently digitized and saved as x/y-coordinates using tpsDIG 2.16 [22]. Where possible, the second ungual was chosen. Although the true curvature of the claws is defined by the keratinous sheath covering the bone, only the dimensions of the bony manual unguals were considered in this study to create a consistent dataset, as the keratinous sheath is rarely preserved in theropods.

FFT and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed on the dataset using PAST [23], including the programs Hangle, Hmatch and Hcurve designed by Crompton & Haines [24]. Outlines were smoothed 10 times to eliminate pixel noise, and 23 Fourier harmonics were found to sufficiently describe the outlines. Two datasets were analysed: (i) all sampled taxa (theropods and mammals) and (ii) theropods only.

(b). Digital models and finite-element analysis

FEAs are based on the manual unguals of five therizinosaurian taxa: Falcarius utahensis (UMNH VP 14587), Nothronychus graffami (UMNH VP 16420) (both Natural History Museum of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), Beipiaosaurus utahensis (IVPP V11559), Alxasaurus elesitaiensis (IVPP 88402) (both Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Beijing, People's Republic of China) and Therizinosaurus cheloniformes. For the duration of this study, the manuals of Therizinosaurus were inaccessible (C. Tsogtbaatar 2012, personal communication). A museum quality cast of this specimen, housed at the Sauriermuseum Aathal, Switzerland, was therefore used in this study instead. The manual unguals of the five aforementioned taxa were digitized using a photogrammetry approach [25] and Agisoft Photoscan Standard. A Panasonic DMC-FZ5 5 megapixel camera was used to acquire between 40 and 60 photographs of each specimen. The comparably simple morphology of the manual unguals ensured accurate digitization using this method. The digital models were imported into Avizo v. 7.0 (Visualization Science Group) to remove extraneous material (e.g. artefacts of the photogrammetry reconstruction) and remove cracks or holes in the specimens (see also electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

The surface models were scaled to the same surface area (representing the average surface area of all sampled unguals) [26] and were imported into Hypermesh (v. 11, Altair Engineering) to create solid mesh FE models of suitable resolution (approx. 1 600 000 four-noded tetrahedral elements) [27]. Material properties were assigned in Hypermesh for bone (E = 20.49 GPa, ν = 0.40), which was treated as isotropic and homogeneous. Further validation models were analysed incorporating hollow internal structure and a keratin sheath (E = 1.04 GPa, ν = 0.40) (electronic supplementary material, figure S6), to evaluate the effects of these components. All models were constrained from rigid body motion at the joint surfaces and the flexor tubercles. Three different functional scenarios were simulated for each ungual morphology/taxon (analogue to hypotheses 1, 7 and 15 in [28]): (i) a scratch-digging function with the force centred on the ventral surface of the ungual tip, (ii) a hook-and-pull function with the force spread evenly along the ventral surface of the ungual and (iii) a piercing function with the force directed opposite to the ungual tip. A total force of 400 N were applied in each scenario, as used in [29] for Velociraptor. While this value may underestimate the forces the forelimbs of the larger therizinosaurian taxa in this study might produce, it is still informative in the comparative context of the performed analyses. All models were imported into Abaqus (v. 6.10; Simulia) for analysis and post processing.

3. Results

(a). Shape analysis

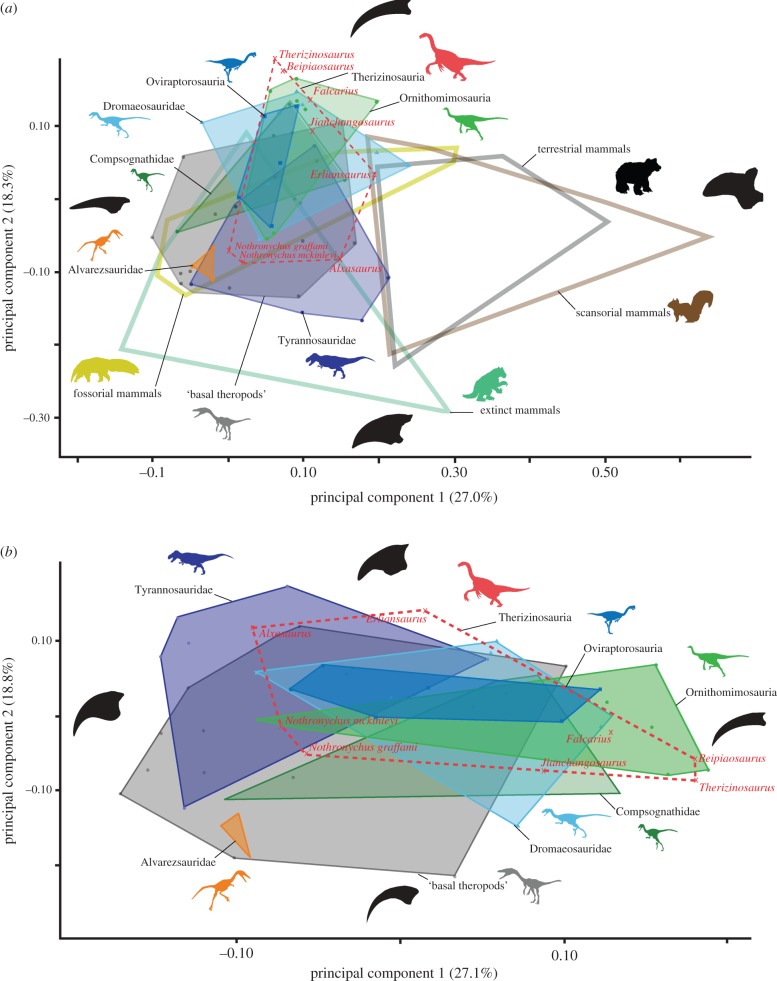

The PCAs (figure 2) for both datasets (theropods + mammals, theropods only) show that a large portion of the ungual shape variation is summarized by PC1 (27.0, 27.1%) and PC2 (18.3, 18.8%). In the combined dataset, PC1 and PC2 largely describe the elongation of the unguals, whereas in the theropod dataset PC1 more distinctly reflects the variation in the elongation and PC2 the variation in the curvature of the individual unguals. The pattern of morphospace occupation is similar in both datasets for theropods. In both datasets, no apparent separation in the morphospace is visible for the different theropod clades, with a large overlap between most groups. The only exception is the Alvarezsauridae, which occupy a small morphospace distinctly separated from all other Maniraptoriformes (although not from all non-coelurosaurian theropods). Other maniraptoriform groups, and in particular the non-carnivorous clades (Therizinosauria, Ornithomimosauria and Oviraptorosauria), largely share a common morphospace, but partly distinct to basal theropods. However, in both datasets, Therizinosauria shows the highest diversity of morphospace occupation, overlapping with the majority of all theropods. It is noteworthy that the possible therizinosauroid Martharaptor greenriverensis is found in a more distant morphospace position than all other therizinosaurian taxa (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional morphospace plots of manual ungual shape based on first two principal component axes for the (a) combined theropod/mammal dataset and for (b) theropods only. (Online version in colour.)

In comparison, both extant and extinct mammals occupy a vastly larger morphospace than theropod taxa. A clear separation in the extant mammals is apparent between predominantly fossorial and scansorial/terrestrial taxa. However, there is largely no distinction between mammalian taxa that use the claws in terrestrial locomotion (or as generalists) and scansorial species. The majority of extinct clawed herbivorous mammals occupy a morphospace distinct to both extant mammals and most theropods. Interestingly, several theropods end up sharing the same morphospace filled by fossorial mammals. Among these, Alvarezsauridae, for which a predominantly fossorial behaviour has been suggested based on forelimb anatomy [20], completely lie within the morphospace of fossorial mammals, close to the extant pangolin (Manis sp.) and pocket gophers (Geomys bursarius). Among Maniraptoriformes, however, a large number of taxa fall outside the functional morphospace of extant mammals.

In the canonical variates plots for the combined dataset (electronic supplementary material, figure S2a), the individual theropod groups are clearly separated from each other but also from extant mammals. This separation is even more pronounced in the theropod dataset (electronic supplementary material, figure S2b). A non-parametric MANOVA test shows that the manual unguals of most theropod groups are significantly (p > 0.05) different from each other and from both extant and extinct mammals (electronic supplementary material, tables S4 and S5).

(b). Finite-element analysis

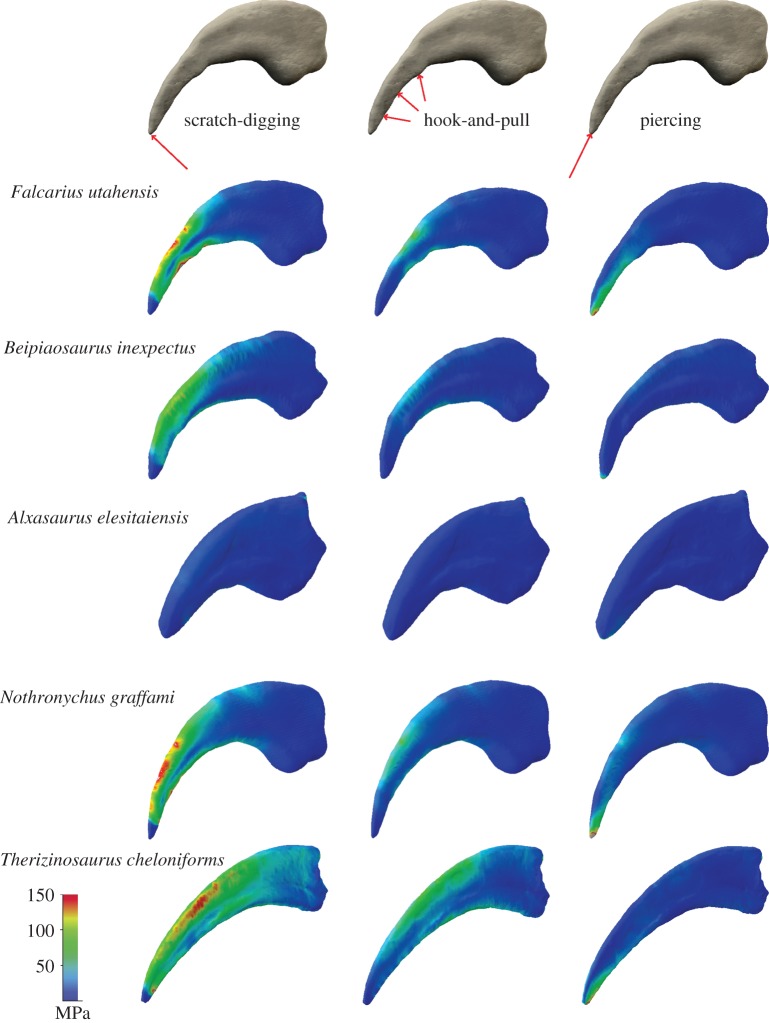

Results of the FEAs show that the individual therizinosaurian ungual morphologies respond differently to the applied forces (figure 3). While the short and compact manual ungual morphology of Alxasaurus recorded only very low von Mises stress, the stress magnitude increased with the curvature and particularly with the elongation of the unguals in the other taxa regardless of the tested functional scenario. Stress was most pronounced in the hypertrophied claw morphology of Therizinosaurus. The same holds true for displacement and strain magnitudes (electronic supplementary material, figures S4 and S5).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Von Mises stress distribution in different therizinosaurian taxa subjected to different functional scenarios. Unguals scaled to same surface area. Contour plots scaled to 150 MPa peak stress. Arrows symbolize applied forces. (Online version in colour.)

Similarly, a comparison between the different functional scenarios reveals that the highest von Mises stress (as well as peak compressive and tensile stress, which coincide with von Mises peak stress), displacement and strain magnitudes were recorded for a scratch-digging function, in which the force is applied on the ventral tip of the claw. In this scenario, stress and strain hot-spots were focused along the dorsal surface of the claws and were again most pronounced in the elongate claws of Therizinosaurus, Nothronychus and Falcarius. By contrast, the hook-and-pull scenario resulted in lower magnitudes than scratch-digging, but with a similar pattern of stress distribution. The overall lowest magnitudes were found in the scenario simulating a piercing function with the force directed opposite the claw tip. In this scenario, stress and strain hot-spots occurred along the ventral surface of the tip with the rest of the claw largely unaffected.

Further analysis incorporating a keratinous claw sheath and internal morphology produced a comparable pattern of stress distribution, with only the magnitudes different (electronic supplementary material, figure S6). Surprisingly, the presence of a keratin sheath has largely no effect for the hollow claw configuration, whereas stress magnitudes are slightly decreased in the solid keratin-bearing model. This fact indicates that the presence of a keratinous sheath and internal morphology can be disregarded in a comparative approach, if these parameters are kept constant. However, it should be noted that unlike in the simplified model used in this study, the thickness of the keratin sheath and its attachment to the underlying bone could be variable. Consequently, some of the stress peaks could be alleviated by a thickness gradient.

4. Discussion

The shape analysis and the FEA performed in this study independently suggest a large functional diversity in the claws of Therizinosauria. In spite of this fact, however, no clear correlation between ungual morphology and a concrete function is readily apparent. The biomechanical behaviour of the ungual model of Alxasaurus indicates that the short and compact morphology (found also in Erliansaurus) would be suitable for any of the tested scenarios. In fact, Erliansaurus and Alxasaurus are found at or between the intersections of the morphospaces of the three different extant mammal groups (scansorial, fossorial and terrestrial) in the shape analysis, supporting the assumption that their ungual morphology can be considered to represent a generalist functionality.

By contrast, the more strongly curved and elongate unguals of the other sampled therizinosaurian taxa recorded the highest stress magnitudes when simulating a scratch-digging scenario, indicating this as the most unlikely of the tested functionalities. However, in the shape analysis Nothronychus graffami and N. mckinleyi share a functional space with extant fossorial mammals, whereas the remaining therizinosaurian taxa fall into a functional space distinct to extant or extinct mammals, suggesting a different function, or a combination of functions. Evidence for fossorial behaviour has been documented in a number of dinosaur taxa and for different purposes. This ranges from digging burrows in small ornithischians [30,31] to nest building in sauropods [32] and troodontids [33] and foraging in alvarezsaurids [20]. While the large body size largely rules out the possibility of burrow digging in therizinosaurs, troodontids and dromaeosaurids most probably used their hindlimbs and pedal claws for digging [33,34], as feathering on the forelimbs would have interfered with manus digging [35]. The same can likely be assumed for therizinosaurs and other feathered Maniraptoriformes, such as oviraptorosaurs and ornithomimosaurs. With the exception of alvarezsaurids [20], range-of-motion studies provide a further line of evidence that digging capabilities of the forelimbs can be ruled out in other Maniraptoriformes [19,21,35]. For ornithomimosaurs, which share a similar ungual morphology and morphospace occupation with several therizinosaurian taxa, such as Therizinosaurus and Beipiaosaurus, range-of-motion studies suggested the use of their manus in a hook-and-pull fashion to pull vegetation within reach [19]. Following the results of the FEA and the shared morphospace occupation, a similar function is likely for therizinosaurs possessing elongate and curved unguals. However, if the unguals were used for browsing and pulling down vegetation, it would be expected that the forelimbs served to extend the range of the animal to a point, which cannot be reached by the head [36]. Therizinosaurian taxa, in which both cervical as well as forelimb elements are preserved, indicate that the neck is nearly equal in length or longer than the forelimbs (Nothronychus: neck = 118% of forelimbs, Alxasaurus: neck = 105% of forelimbs, Falcarius: neck = 103% of forelimbs). Thus, pulling of vegetation makes sense only, if large elements in reach were pulled down, in order to get at parts that were out of reach (e.g. long branches pulled down by a basal part).

Apart from digging and grasping, numerous locomotor-independent manus claw functions have been discussed for (mostly non-theropod) dinosaurs, including defence [37], intraspecific combat [38], trunk grasping for stabilization during high browsing [39], sexual display [3] or mate-gripping during copulation [40]. Based on this study, none of these functions can clearly be confirmed or disregarded. Surprisingly, and despite their frequent portrayal as such in popular culture, there is no evidence that the hypertrophied claws of Therizinosaurus or other taxa would have been used in a defensive or aggressive context, although it seems plausible that the animal would make use of its claws when threatened. Similarly, the fragmentary fossil record for therizinosaurs makes it difficult to evaluate whether the enlarged unguals could represent a sexually dimorphic feature, as in some extant turtles [41].

The plesiomorphic condition for theropod claw function is assumed to have been grasping prey [42,43]. This function is consistent with a carnivorous diet and biomechanically similar to digging. Consequently, the majority of basal (non-coelurosaurian) theropods in the shape analysis overlap in morphospace with that of fossorial mammals (figure 2a). Basal theropods exhibit plesiomorphically short claws with strong ungual curvature [21], a morphology which is designed to withstand high forces [44], which occur in both grasping prey and digging. Coelurosaurs, and in particular Maniraptoriformes, however, deviate from this plesiomorphic condition and show a diversification of ungual morphology and functionality, resulting in an expansion of the occupied morphospace (figure 2). Maniraptoriformes are characterized by dietary diversification and the acquisition of herbivory in several clades, as shown by numerous modifications and the high plasticity of the cranial skeleton [45,46]. The variation in maniraptoriform manual ungual form and function parallels this trend, suggesting that dietary diversification is reflected not only in the cranial skeleton, but also in the postcranial elements. Interestingly, the morphological and functional disparity in theropods did not result in an expansion of the morphospace to the extent seen in extant and extinct mammals. This might be partially explained by the fact that theropods did not use the manual claws for climbing or quadrupedal locomotion, whereas no large bipedal mammals exist today that provide an extant analogue. The large herbivorous extinct mammals in this study, some of which have been used as examples for the convergent evolution in comparison to therizinosaurs [10], occupy a morphospace largely distinct to Maniraptoriformes and extant mammals.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study confirm the hypothesis that the manual unguals of therizinosaur dinosaurs were morphologically and functionally diverse. However, despite independently derived evidence from the shape and FEAs, it is not always possible to correlate ungual morphology with a specific function. The results suggest that the short and compact claws of Alxasaurus and Erliansaurus were used in a generalist fashion, whereas the elongate and enlarged claws of other therizinosaurian taxa such a Therizinosaurus, Beipiaosaurus and Falcarius, prone to higher stress and strain magnitudes, would not have been optimized for a fossorial function. Instead, this ungual design was adapted for a hook-and-pull function to reach for vegetation during foraging. However, such a functional diversification is not solely restricted to Therizinosauria, but can also be found in other groups among Maniraptoriformes. Parallel to numerous cranial modifications related to dietary diversification, maniraptoriform dinosaurs appear to have adapted the plesiomorphic ungual morphology for various functions, indicating that dietary plasticity was an important driver for morphological and functional disparity in theropod dinosaurs. While this becomes apparent in the expansion of the morphospace occupation, certain constraints may have been imposed on ungual morphology in comparison to ungual morphology in both extant and extinct mammals.

Acknowledgements

Mike Getty (UMNH), Zheng Fang (IVPP), Köbi Siber and Thomas Bolliger (Sauriermuseum Aathal) are thanked for access to specimens. Jen Bright, Imran Rahman and Emily Rayfield (University of Bristol) provided helpful suggestions that greatly improved this paper. Associate editor John Hutchinson, Heinrich Mallison and an anonymous reviewer are thanked for helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding statement

Funding by the Software Sustainability Institute and the Volkswagen Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Clark JM, Maryanska T, Barsbold R. 2004. Therizinosauroidea. In The Dinosauria (second edition) (eds Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmolska H.), pp. 151–164. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barsbold R. 1976. New data on Therizinosaurus (Therizinosauridae, Theropoda). Transactions, Joint Soviet–Mongolian Paleontological Expedition 3, 76–92. [In Russian.] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanno LE. 2006. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the primitive therizinosauroid Falcarius utahensis (Theropoda, Maniraptora): analyzing evolutionary trends within Therizinosauroidea. J. Vertebrate Paleontol. 26, 635–650. ( 10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[636:TPGAFO]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanno LE. 2010. A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 8, 503–543. ( 10.1080/14772019.2010.488045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul GS. 1984. The segnosaurian dinosaurs: relics of the prosauropod–ornithischian transition? J. Vertebrate Paleontol. 4, 507–515. ( 10.1080/02724634.1984.10012026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanno LE, Gillette DD, Albright LB, Titus AL. 2009. A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in ‘predatory’ dinosaur evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3505–3511. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautenschlager S, Witmer LM, Altangerel P, Rayfield EJ. 2013. Edentulism, beaks, and biomechanical innovations in the evolution of theropod dinosaurs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20 657–20 662. ( 10.1073/pnas.1310711110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillette DD. 2007. Therizinosaur: mystery of the sickle-clawed dinosaur. Plateau: Land and People of the Colorado Plateau, 4/2 4, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozhdestvensky AK. 1970. Giant claws of enigmatic Mesozoic reptiles. Paleontol. J. 1970, 131–141. [In Russian.] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell DA, Russell DE. 1993. Mammal–dinosaur convergence—evolutionary convergence between a mammalian and dinosaurian clawed herbivore. Natl Geogr. Res. Explor. 9, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Peng C, You H, Lamanna MC, Harris JD, Lacovara KJ, Zhang J. 2007. A large therizinosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Northwestern China. Acta Geol. Sin. 81, 539–549. ( 10.1111/j.1755-6724.2007.tb00977.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkland JI, Wolfe DG. 2001. First definitive therizinosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from North America. J. Vertebrate Paleontol. 21, 410–414. ( 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0410:FDTDTF]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nessov LA. 1995. Dinosaurs of Northern Eurasia: new data about assemblages, ecology and paleobiogeography [in Russian], p. 156 St Petersburg, Russia: Scientific Research Institute of the Earth's Crust, St Petersburg State University. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feduccia A. 1993. Evidence from claw geometry indicating arboreal habits of Archaeopteryx. Science 259, 790–793. ( 10.1126/science.259.5096.790) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glen CL, Bennett MB. 2007. Foraging modes of Mesozoic birds and non-avian theropods. Curr. Biol. 17, R911–R912. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pike AVL, Maitland DP. 2004. Scaling of bird claws. J. Zool. 262, 73–81. ( 10.1017/S0952836903004382) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler DW, Freedman EA, Scannella JB. 2009. Predatory functional morphology in raptors: interdigital variation in talon size is related to prey restraint and immobilisation technique. PLoS ONE 4, e7999 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0007999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birn-Jeffery AV, Miller CE, Naish D, Rayfield EJ, Hone DWE. 2012. Pedal claw curvature in birds, lizards and Mesozoic dinosaurs—complicated categories and compensating for mass-specific and phylogenetic control. PLoS ONE 7, e50555 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0050555) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholls EL, Russell AP. 1985. Structure and function of the pectoral girdle and forelimb of Struthiomimus altus (Theropoda: Ornithomimidae). Palaeontology 28, 643–677. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senter P. 2005. Function in the stunted forelimbs of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda), a dinosaurian anteater. Paleobiology 31, 373–381. ( 10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0373:FITSFO]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senter P, Parrish JM. 2005. Functional analysis of the hands of the theropod dinosaur Chirostenotes pergracilis: evidence for an unusual paleoecological role. PaleoBios 25, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohlf FJ. 2010. TpsDig 2. Stony Brook, NY: Department of Ecology and Evolution. State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. 2001. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crampton JS, Haines AJ. 1996. Users’ manual for programs Hangle, Hmatch and Hcurve for the Fourier shape analysis of two-dimensional outlines. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Science Report 96, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falkingham PL. 2011. Acquisition of high-resolution three-dimensional models using free, open-source, photogrammetric software. Palaeontol. Electron. 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dumont ER, Grosse I, Slate GJ. 2009. Requirements for comparing the performance of finite element models of biological structures. J. Theor. Biol. 256, 96–103. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.08.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bright JA, Rayfield EJ. 2011. Sensitivity and ex vivo validation of finite element models of the domestic pig cranium. J. Anat. 219, 456–471. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01408.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senter P. 2006. Forelimb function in Ornitholestes hermanni Osborn (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Palaeontology 49, 1029–1034. ( 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00585.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning PL, Margetts L, Johnson MR, Withers PJ, Sellers WI, Falkingham PL, Mummery PM, Barrett PM, Raymont DR. 2009. Biomechanics of dromaeosaurid dinosaur claws: application of X-ray microtomography, nanoindentation, and finite element analysis. Anat. Rec. 292, 1397–1405. ( 10.1002/ar.20986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman DB, Sues H-D, Witmer LM, Coria RA. 2004. Basal Ornithopoda. In The Dinosauria (second edition) (eds Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmolska H.), pp. 393–412. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varricchio DJ, Martin AJ, Katsura Y. 2007. First trace and body fossil evidence of a burrowing, denning dinosaur. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 1361–1368. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.0443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiappe LM, Schmitt JG, Jackson FD, Garrido A, Dingus LG-T. 2004. Nest structure for sauropods: sedimentary criteria for recognition of dinosaur nesting traces. Palaios 19, 89–95. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varricchio DJ, Jackson F, Borkowski JJ, Horner JR. 1997. Nest and egg clutches of the dinosaur Troodon formosus and the evolution of avian reproductive traits. Nature 385, 247–250. ( 10.1038/385247a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson EL, Hilbert-Wolf HL, Wizevich MC, Tindall SE, Fasinski BR, Storm LP, Needle MD. 2010. Predatory digging behavior by dinosaurs. Geology 38, 699–702. ( 10.1130/G31019.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senter P. 2006. Comparison of forelimb function between Deinonychus and Bambiraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae). J. Vert. Paleontol. 26, 897–906. ( 10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[897:COFFBD]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Upchurch P. 1994. Manus claw function in sauropod dinosaurs. Gaia 10, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman DB. 1980. On the ornithischian dinosaur Iguanodon bernissartensis from Belgium. Mémoires Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 178, 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakker RT. 1987. The return of the dancing dinosaurs. In Dinosaurs past and present (eds Czerkas SJ, Olson EC.), pp. 38–69. Los Angeles, CA: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanimoto M. 1991. Sauropod tripodal ability. Mod. Geol. 161, 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowler DW, Hall LE. 2010. Scratch-digging sauropods, revisited. Hist. Biol. 23, 27–40. ( 10.1080/08912963.2010.504852) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warner DA, Tucker JK, Filoramo NI, Towey JB. 2006. Claw function of hatchling and adult red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans). Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 5, 317–320. ( 10.2744/1071-8443(2006)5[317:CFOHAA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sereno PC. 1993. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the basal theropod Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis. J. Vert. Paleontol. 13, 425–450. ( 10.1080/02724634.1994.10011524) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gishlick AD. 2001. The function of the manus and forelimb of Deinonychus antirrhopus and its importance for the origin of avian flight. In New perspectives on the origin and early evolution of birds (eds Gauthier J, Gall LF.), pp. 301–318. New Haven, CT: Yale Peabody Museum. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattheck C, Reuss S. 1991. The claw of the tiger: an assessment of its mechanical shape optimization. J. Theor. Biol. 150, 323–328. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80431-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zanno LE, Makovicky PJ. 2011. Herbivorous ecomorphology and specialization patterns in theropod dinosaur evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 232–237. ( 10.1073/pnas.1011924108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brusatte SL, Sakamoto M, Montanari S, Harcourt Smith WEH. 2012. The evolution of cranial form and function in theropod dinosaurs: insights from geometric morphometrics. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 365–377. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02427.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]