Abstract

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy affecting women of reproductive age. Its clinical expression is diverse, including metabolic, behavioral and reproductive effects, with many affected by obesity and decreased quality of life. Women with PCOS who have undergone surgically-induced weight loss have reported tremendous benefit, not only with weight loss, but also improvement of hyperandrogenism and menstrual cyclicity.

Methods

In a rat model of PCOS achieved via chronic administration of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) exposure, we investigated the ability of bariatric surgery, specifically vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG), to ameliorate the metabolic, behavioral and reproductive abnormalities invoked by this PCOS model.

Results

We found that DHT-treatment combined with exposure to a high-fat diet resulted in increased body weight and body fat, impaired fasting glucose, hirsutism, anxiety and irregular cycles. VSG resulted in reduced food intake, body weight and adiposity with improved fasting glucose and triglycerides. VSG induced lower basal corticosterone levels and attenuated stress responsivity. Once the DHT levels decreased to normal, regular estrous cyclicity was also restored.

Conclusion

VSG, therefore, improved PCOS manifestations in a comprehensive manner and may represent a potential therapeutic approach for specific aspects of PCOS.

Keywords: PCOS, obesity, bariatric surgery, anxiety, stress

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy in women of reproductive age, with estimates of prevalence as high as 15%1. There is a broad spectrum of phenotypes, but all have a combination of oligo- or anovulation, clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries2. PCOS is associated with an increased risk of metabolic disturbances including insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose tolerance, gestational diabetes and type-2 diabetes (T2DM)3, 4 ; with all of these exacerbated by obesity1. Reproductive comorbidities include infertility1 and increased risk of endometrial cancer5 due to oligo- or anovulation. Other health risks include cardiovascular disease6, 7, dyslipidemia8, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease9 and sleep apnea10. Stress-related psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety, are also associated with PCOS11, 12. It is unclear whether this association is due to psychosocial elements or directly related to the etiology of PCOS. Given its unknown etiology, treatment for PCOS is focused on alleviating symptoms.

Obesity is associated with PCOS and exacerbates many of its comorbidities1. Obesity affects approximately one third of U.S. adults (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)13, with few effective treatments. Weight loss from the traditional lifestyle modification method of diet and exercise is not commonly achieved nor sustained14–16. Though a healthy lifestyle can improve the symptoms of PCOS (i.e. insulin resistance, body composition and hyperandrogenism), there is little evidence that it improves glucose tolerance, lipid profiles, reproductive outcomes or quality of life17. Additionally, pharmacologic weight loss agents are limited and are associated with relatively small amounts of weight loss18.

Bariatric surgery has gained popularity as an effective weight loss treatment. It causes substantial, sustained weight loss superior to other weight loss strategies. Furthermore, bariatric surgery reduces the incidence of T2DM19, heart disease20 and cancer21. For many it also eliminates the need for pharmacological treatment of T2DM, hypertension and hyperlipidemia22. Promising but limited data suggest that bariatric surgery may be an effective treatment option in women with PCOS. PCOS women undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion lost weight and had improved insulin resistance, restoration of regular menstrual cycles and improved or resolved clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism23,24.

The goal of the present study was to determine whether surgically-induced weight loss was able to reverse the metabolic, behavioral and reproductive consequences of chronic androgens in our rat model of PCOS, if allowed to wear off. First we induced hyperandrogenemia using chronic exposure to elevated levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), as it has previously shown metabolic and reproductive patterns similar to women with PCOS25, 26 ; animals were placed on an obesogenic high-fat diet (HFD). We assessed the effects of DHT and HFD on metabolic parameters (body weight, body composition and glucose tolerance) and anxiety-like behaviors using the elevated plus maze (EPM). We also determined the pattern of estrous cyclicity as a measure of reproductive health. We then performed vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG). We assayed plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the absence of stress and during novel environment exposure (stressed condition) as an index of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function. We hypothesized that VSG surgery would ameliorate the metabolic, behavioral and reproductive complications in this rat model of PCOS.

METHODS

Animals

All procedures for animal use were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Forty-six young (20–24 d old), female Long-Evan rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN; 35–49 g) were individually housed and maintained in a room on a 12/12-h light/dark cycle at 25 °C and 5 0–60% humidity. Following acclimatization to the facilities, rats were divided into 2 body weight- and fat mass-matched groups (DHT and placebo). Pellet implantation occurred 4 d after arrival. Animals were given ad libitum access to water and palatable HFD (#D03082706, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, 4.54 kCal/g; 41% fat) for 6 wk prior to gastric surgery. Food hoppers placed in each cage were weighed daily or twice weekly to measure food intake. Six wk post-pellet implantation, animals were divided into 4 body weight- and fat mass-matched groups of surgical animals: a) placebo pellet and receiving sham-VSG (S-Control; n = 10), b) placebo pellet and receiving VSG surgery (V-Control; n = 13) c) DHT pellet and receiving sham-VSG (S-DHT; n = 10), or d) DHT pellet and receiving VSG surgery (V-DHT; n = 13). Animals were killed after an additional 6 wk.

Pellet implantation

At postnatal d 24–28, anesthetized (isoflurane) female pups were implanted subcutaneously with a 60-d continuous-release-pellet containing 5.0 mg of 5α-DHT or placebo (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). This model and dose were chosen based on their ability to induce both ovarian and metabolic characteristics of PCOS25 and to mimic the hyperandrogenic state in women with PCOS. The DHT pellets were intended to wear off in the post-operative period to garner whether the changes induced by hyperandrogenism are permanent (this has not been previously demonstrated) or able to modulated by the improved metabolic milieu post-bariatric surgery.

Gastric surgery

Pre-operative care

Four days prior to surgery, body composition was assessed using an Echo magnetic resonance imaging whole-body composition analyzer (EchoMedical Systems, Houston, TX). Animals were solid-food restricted for 24 h and given Osmolite OneCal liquid diet.

VSG

VSG was performed as previously described27. Briefly, it consisted of a midline abdominal laparotomy with exteriorization of the stomach. The lateral 80% of the stomach was excised using an ETS 35-mm staple gun, leaving a tubular gastric remnant in continuity with the esophagus. This gastric sleeve was then reintegrated into the abdominal cavity and the abdominal wall was closed in layers.

Sham-VSG

An abdominal laparotomy was performed with analogous isolation of the stomach. Light manual pressure was applied to the exteriorized stomach with blunt forceps along a vertical line between the esophageal sphincter and the pylorus. The abdominal wall was closed in layers.

Post-operative care

Following surgery, rats received special care for 3 d, consisting of twice-daily subcutaneous injections of warm saline 5 mL, Bupronex® 0.25 mL (0.05mg/kg), and once-daily Metacam® 0.25 mL (0.5mg/kg). Animals were maintained on Osmolite until food was returned 3 d following surgery. A wire grate was used for 7 d postoperatively to prevent rats from eating bedding.

Body weight, composition and food intake

Food intake and body weights were measured twice per week for the entirety of the study, with the exception of 10 d following surgery, during which time they were measured daily. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on all rats at 1, 6 and 12 wk to determine fat and lean body composition.

Estrous cycle

The stage of the estrous cycle was determined during 5 consecutive days at 4, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 12 wk. Cells were obtained by vaginal lavage and were stained with DipQuick staining kit (Jorgansen Laboratories, Inc., Loveland, CO) for the determination of the estrous cycle phase28.

Glucose tolerance tests (GTT)

GTT was performed at 5 wk. Rats were fasted for 8 h. After a baseline blood sample was taken (0 min), 50% D-glucose (Phoenix Pharmaceutical, St. Joseph, MO) was injected ip or gavaged. Blood glucose was measured at baseline (0), 15, 30, 45, 60 and 120 min after glucose administration on duplicate samples using Accu-chek glucometers and test strips (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). All blood samples were obtained from the tip of the tail vein of freely moving rats. Each rat received a dose of glucose equal to 1.25 g/kg body weight for the ip GTT. Rats were excluded from the data analysis if they did not exhibit a rise in blood glucose of greater than 20 mg/dL in the first 15 min after injection or if they exhibited diarrhea, as this indicates that the glucose injection did not enter the ip cavity. Plasma insulin was measured at 0 and 15 min.

Insulin tolerance test (ITT)

Eight-h fasted rats were injected ip with insulin (0.5 U/kg). Blood glucose was measured at baseline (0), 15, 30, 45 and 60 min after injections with Accu-chek glucometers and test strips. All blood samples were obtained from the tip of the tail vein of freely moving rats.

Diet preference testing

During wk 5, 3 pure macronutrient diets (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN; TD.02521 (carbohydrate), TD.02522 (fat) and TD.02523 (protein)) were presented in separate containers simultaneously for 4 d. Daily food intake of each macronutrient was recorded.

Elevated plus maze (EPM)

An EPM test was performed during wk 6. Animals were placed in a holding room approximately 4 h before the onset of the dark phase to acclimate. The challenge was performed at 6 min intervals commencing 15 min after the onset of the dark phase. The apparatus comprised of a PVC maze with two open (40×10) and two enclosed (40×10×20) arms. The arms radiated from a 10 cm central square. The entire apparatus was elevated 60 cm off the floor. For testing, each animal was placed on the center square of the maze facing the same open arm. Behavior was recorded from an overhead ceiling camera for 5 min. Video files were captured and saved for later scoring. The maze was cleaned after each rat was tested. A number of behavioral measures were analyzed, which included standard measures of exploration and anxiety-like behavior as well as additional measures of fear and arousal. Parameters were measured using the Topscan program CleverSys (CleverSys Inc. Reston, VA). Several parameters were scored including arm time (open and closed), arm entries (open and closed) and general locomotor activity.

Novel environment challenge

Novel environment challenge was performed on POD 28 (wk 11) commencing 2 h after the onset of the light cycle. Each animal was brought from the housing room into the procedure room (T=0) and a blood sample taken quickly by tail clip for later measurement of plasma ACTH and corticosterone. It was then placed immediately into a Plexiglas cylinder approximately 25 cm in diameter and lined with excretory paper for 5 min, after which the animal was returned to the home cage. Additional tail-blood samples were quickly collected at 15, 30, 60 and 120 min from the unrestrained rat and returned to the home cage.

Insulin, Lipids and Plasma Hormone Assays

Insulin was measured from fasting plasma. Cholesterol and triglycerides were measured from plasma taken after an 8 h fast. Blood was cold centrifuged, and plasma was stored at −80 °C until they were assessed. Insulin was measured using ELISA (CrystalChem, Inc., Downers Grove, IL). Cholesterol and triglycerides were measured via colorimetric assays using Infinity Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA).

Corticosterone was measured by 125I radioimminoassay (RIA) kits from ICN Biochemicals (Cleveland, OH) The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation are 7.1 and 7.2%.respectively. ACTH plasma concentration was measured by RIA using 125I RIA kit from DiaSorin (Stillwater, MN). The limit of detection for this assay was 15 pg/ml, and intra- and interassay coefficients were 6.3 and 6.0%, respectively. For each assay performed, control samples with known concentrations of hormone (usually low, normal, and high; provided by the manufacturer) were included to assess performance and reliability.

Ovary Morphology

The ovaries were longitudinally and serially sectioned at 10 µm. Sections were mounted on a glass slide, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined under a conventional birefringence microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t test, Chi-square or 2-way and 1-way ANOVA, where appropriate. Significant differences between groups were followed by Tukey or Bonferroni post hoc tests. All results are given as means ± SEM. Results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

DHT treatment causes increased body weight, food intake and fat mass

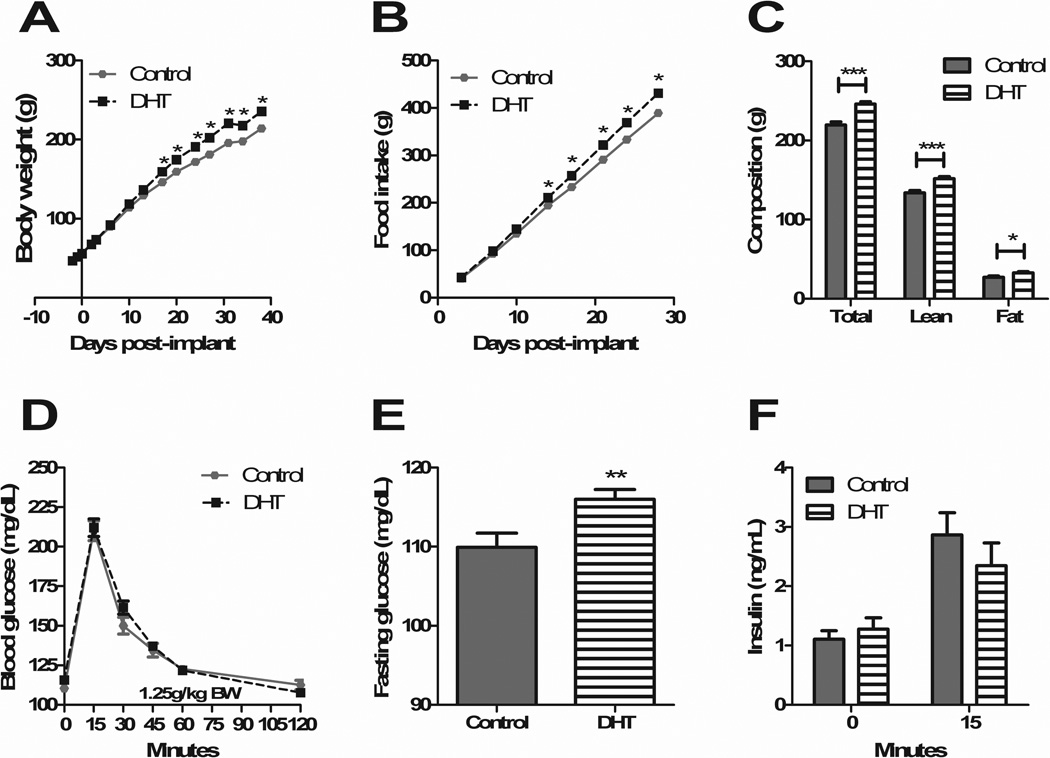

DHT-treated animals had significantly greater body weight starting 17 d after pellet placement (p<0.001) (Figure 1A). This was accompanied by greater food intake by DHT-treated animals starting 14 d post-implant (p<0.01) (Figure 1B). The increase in body weight was due to an increase in both lean (p<0.0001) and fat mass (p<0.05), as measured 4 d prior to gastric surgery (Figure 1C). There were no differences in body length (naso-anal distance), as measured at the time of gastric surgery and sacrifice. Four wk after pellet placement, there were no significant differences in glucose tolerance (Figure 1D), however DHT animals did have significantly higher fasting glucose levels (control 109.9 ± 1.779 SEM; DHT 116.0 ± 1.217, p<0.01) (Figure 1E). There were no differences between groups in regard to insulin levels at baseline and 15 min (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. DHT treatment causes increased body weight, food intake, fat mass and impaired fasting glucose.

DHT-treated animals had significantly greater body weight starting 17 d after pellet placement (A), accompanied by greater food intake starting at 14 d (B). DHT-treated animals had greater lean and fat mass (C). There were no differences in glucose handling (D); fasting glucose, however, was impaired in DHT-treated animals (E). There were no differences in insulin levels at baseline or 15 min (F). All data are presented as mean ±SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

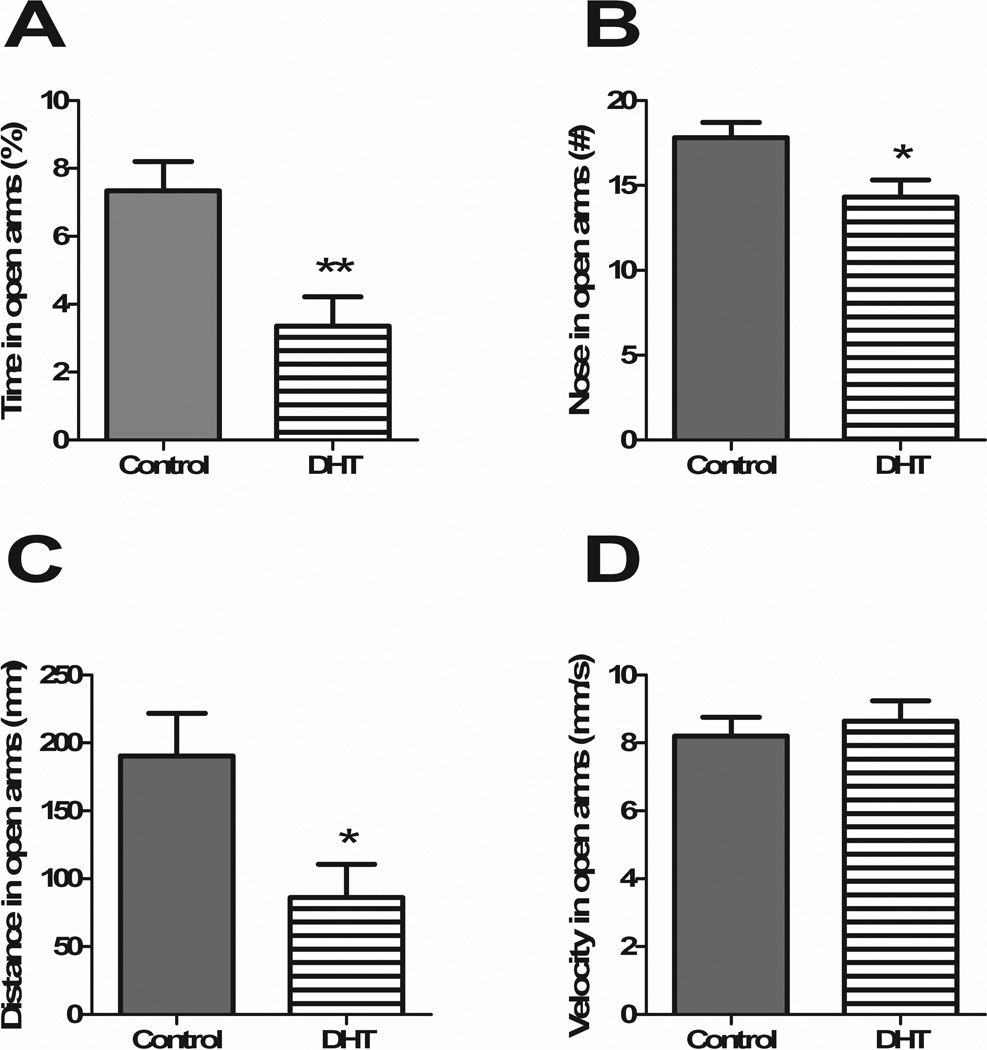

DHT treatment causes a behavioral phenotype in the EPM

Animals performed in the EPM for a 5 min interval following the onset of the dark phase during wk 6. DHT-treated animals spent significantly less time in the open arms (p<0.01) (Figure 2A), had fewer entrances to the open arms (p<0.05) (Figure 2B) and traveled less distance in the open arms (p<0.05) (Figure 2C). No differences emerged in the latency to enter the open arms or the velocity traveled in the open arms (Figure 2D). Anxiety-related behavior was thus increased in DHT-treated animals.

Figure 2. DHT treatment causes a behavioral phenotype in the EPM.

DHT-treated animals showed greater anxiety-like behavior in the EPM as demonstrated by less time in the open arms (A), fewer entrances to the open arms (B) and less distance traveled in the open arms (C). There were no differences in animal velocity in the open arms (D). All data are presented as mean ±SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DHT treatment does not result in food preference differences

When presented with a choice of 3 pure macronutrient diets (carbohydrate, fat and protein), no differences were observed between the DHT and control groups. All rats consumed the most kCal in fat followed by carbohydrate and then protein. There was a significant difference in total kCal consumed, with DHT rats consuming less than controls during this 4 d experiment (p<0.05) (data not shown). This decrease in consumption varied from the remainder of the study, when DHT rats consistently consumed more than controls.

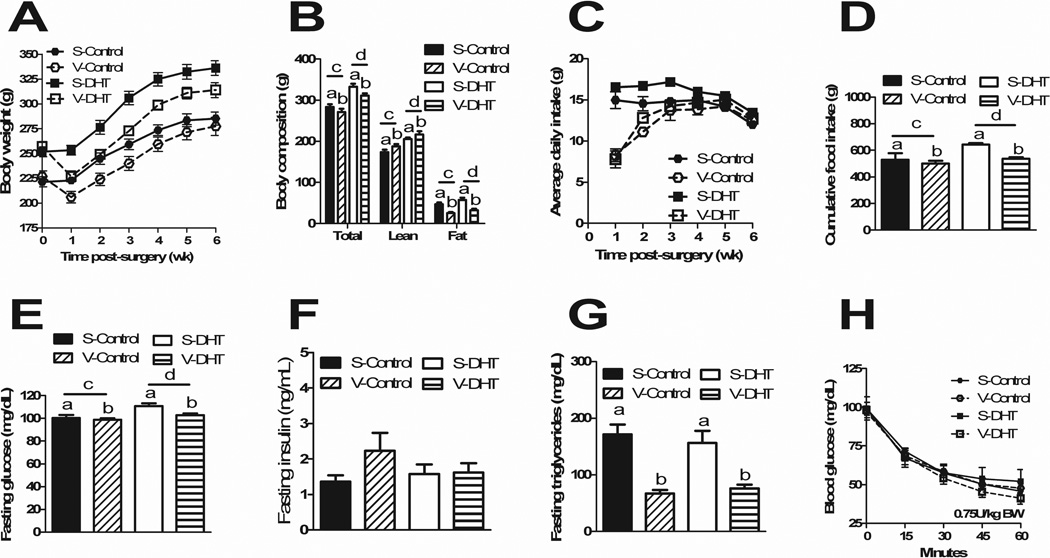

VSG resulted in loss of excess body weight and fat mass gained on HFD

Following surgery, V-Control and V-DHT animals lost a significant amount of body weight compared to S-Control and S-DHT animals starting 1 wk after surgery (p<0.001) (Figure 3A). V-DHT animals maintained a lower body weight than S-DHT animals for the entirety of the experiment (p<0.05). Body composition was measured at 31 d following surgery. S-DHT and V-DHT animals maintained higher lean (p<0.0001) and fat mass (p<0.05) than their control counterparts. V-Control and V-DHT had higher lean mass than the S-Control and S-DHT animals (p<0.05), respectively, while demonstrating lower fat mass (p<0.0001) (Figure 3B). Average daily food intake was decreased in the V-Control and V-DHT animals for the first 4 wk post-operatively (p<0.0 5) (Figure 3C). There was no hyperphagia by VSG animals once recovered, thereby VSG animals cumulatively consumed less than their sham counterparts over the entirety of the experiment (p<0.0001), while DHT animals cumulatively consumed more than controls (p<0.5) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. VSG results in overall metabolic improvements.

Post-operative body weights were lower in VSG animals as compared to Shams (A). VSG animals had higher lean mass and lower fat mass than shams, while DHT animals maintained higher lean and fat mass than controls (B). Average daily food intake was decreased in the VSG animals for the first 4 wk post-operatively (C). VSG animals cumulatively consumed less than shams, with DHT animals cumulatively consuming more than controls (D). VSG animals had improved fasting glucose with DHT animals maintaining higher fasting glucose levels than controls (E). No differences existed in fasting insulin levels (F) and VSG animals had improved triglyceride levels irrespective of group (G). No differences in blood glucose levels were observed during the insulin tolerance tes. All data are presented as mean ±SEM.

At 2 wk post-operatively, although there was no improvement in glucose tolerance curves, an improvement in fasting glucose levels was observed in VSG groups (p<0.001), and levels were lower in control groups compared to DHT (p<0.05) (Figure 3E). There were no differences in fasting insulin levels (Figure 3F). VSG animals had significant improvement in fasting triglyceride levels (p<0.0001) (Figure 3G); fasting cholesterol levels did not differ. There were no differences in glucose levels groups during an insulin tolerance test (Figure 3H).

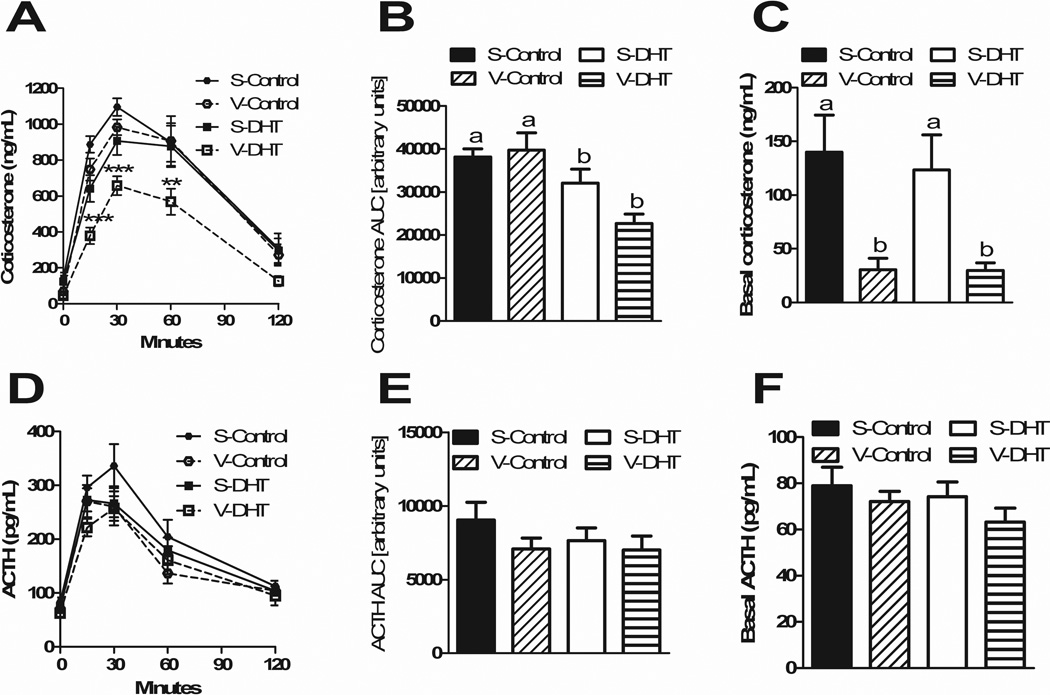

VSG causes blunted corticosterone response to stress

Four weeks after surgery, a novel environment stress test demonstrated that treatment affected both basal and stress-induced corticosterone levels. A blunted corticosterone response was observed in V-DHT animals at 15 (p<0.001), 30 (p<0.001) and 60 min (p<0.01) (Figure 4A). The AUC was lower in both DHT groups compared to controls (p<0.001) (Figure 4B), whereas basal corticosterone levels were lower in both VSG groups compared to sham animals (p<0.0001) ((Figure 4C). There were no differences in ACTH levels at any of the time points (Figure 4D), in their ACTH AUCs (Figure 4E), nor in basal ACTH levels (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. VSG causes a blunted corticosterone response to stress.

A novel environment stress test showed a blunted corticosterone response in V-DHT animals (A). The AUC was lower in DHT animals vs. controls (B). Basal corticosterone levels were lower in VSG animals (C). There were no differences in ACTH levels at any time point (D), in ACTH AUCs (E) nor in basal ACTH (F). All data are presented as mean ±SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

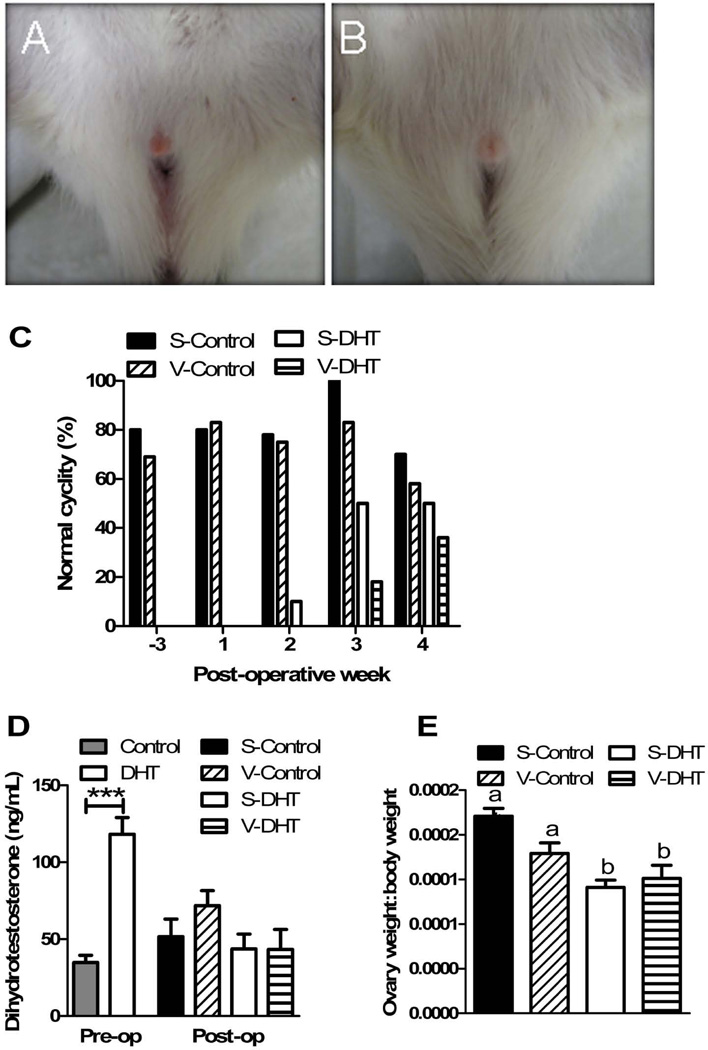

DHT treatment caused hirsutism and disrupted estrous cyclicity

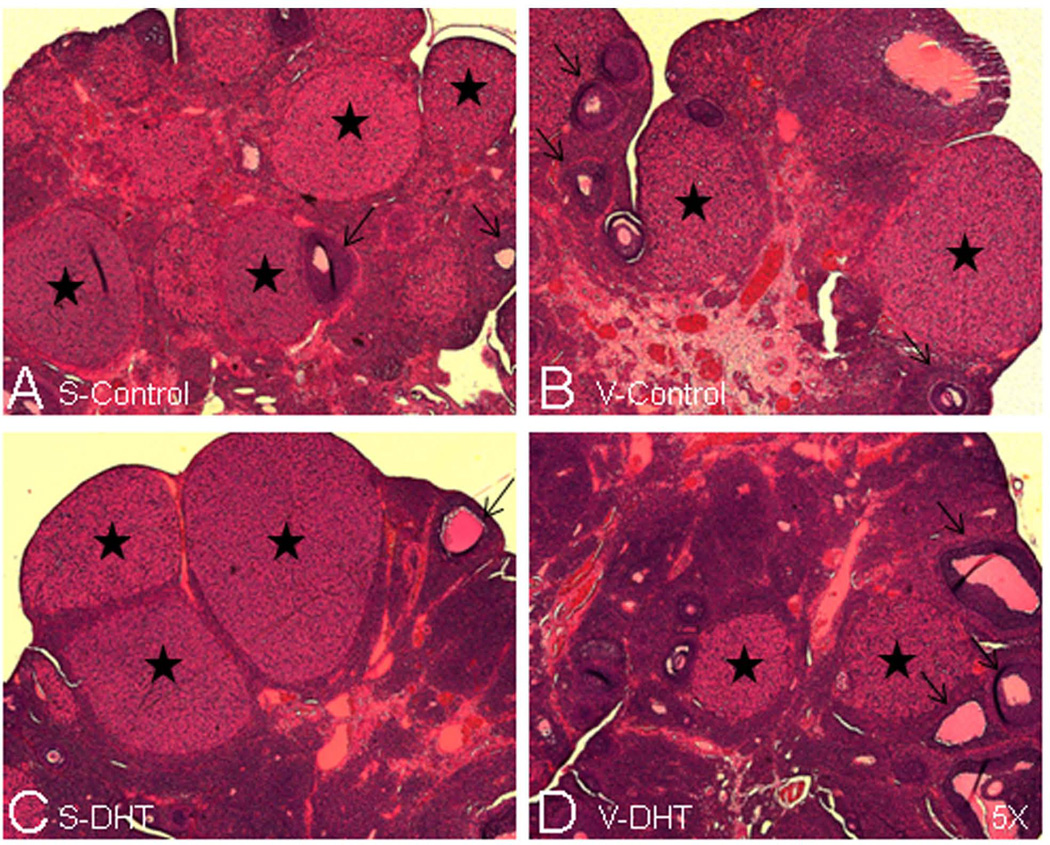

The animals treated with DHT showed longer body hair, with coats resembling those of male rats. They also demonstrated hirsutism, evident at the vaginal openings (Figure 5A and 5B). Prior to VSG surgery, all DHT rats were acyclic (chronic diestrous). Cyclicity was eventually restored. By 2 wk post-operatively, S-DHT animals began to regain normal cyclicity. V-DHT animals were the slowest to regain normal cyclicity, with no statistically significant differences (chi-squared) in cyclicity by 4 wk post-operatively (Figure 5C). Examination of representative HE-stained ovaries from each of the animal groups were also indicative of normal cyclicity, as they showed corpora lutea and follicles at various stages of development (Figure 6A–D)).

Figure 5. DHT treatment causes hirsutism and disrupted estrous cyclicity.

DHT animals developed hirsutism, evident at the vaginal openings (A and B). Prior to VSG surgery and while DHT pellets were active, DHT animals were acyclic. By 2 wk post-VSG, S-DHT animals began to regain normal cyclicity with no differences between groups by 4 wk post-VSG (C). DHT levels were threefold higher in those implanted with DHT pellets, with no differences in levels by 2 wk post-VSG (D). DHT animals had smaller ovaries (E).. All data are presented as mean ±SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 6. Ovarian morphology reverts back to normal following waning of DHT and VSG surgery.

Sections are representative examples of HE-stained ovaries, showing S-control (A), V-control (B), S-DHT (C) and V-DHT (D) rats (magnification, x5.0). All ovaries show corpora lutea (stars) and follicles at different stages (arrows), indicative of normal cyclicity.

Prior to surgery, DHT levels were threefold higher in those with DHT pellets implanted (p<0.0001), with no differences in levels by 2 wk following surgery (Figure 5C). This was consistent with the predicted timing of the pellets wearing off (60 d). The DHT-treated animal groups had smaller ovaries as compared to the control groups (p<0.0001) (Figure 5D).

DISCUSSION

There are no known cures for PCOS. Though diet and exercise are effective for short-term body weight loss, bariatric surgery results in durable, long-term loss of body weight and remission of metabolic comorbidities of obesity; it is unknown whether bariatric surgery is effective in ameliorating the metabolic, stress-related psychiatric and reproductive disorders of PCOS. Here we demonstrated that DHT with HFD results in increased body weight and body fat, impaired fasting glucose, hirsutism, irregular cycles, and anxiety that mimics many of the aspects of human PCOS. VSG performed in this model of PCOS effectively reduced food intake, body weight and body fat with improved fasting glucose and triglyceride levels. Additionally, VSG induced lower basal stress hormone levels and attenuated stress responsivity in V-DHT animals. Following the post-operative waning of the DHT pellet, DHT levels in all groups returned to baseline control levels, and normal cyclicity returned to the DHT rats. The return to normal cycling was slower in the VSG animals as compared to shams, but this difference was transient and there were no differences after 2 wk from when the pellet ceased to deliver DHT.

One of the biggest challenges in studying PCOS in an animal model is the heterogeneity of human phenotypes with an unknown etiology. DHT pellets provide an exogenous androgen source with constant levels not subjected to the same variability as human physiologic androgens. Nevertheless this model has been used extensively26, 29. Our group has previously shown that PCOS rats who underwent vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) lost body weight and adiposity; estrous cyclicity, however, was not restored in the face of continuous exogenous DHT administration in lean rats maintained on standard rodent chow30. Simply, the overriding effects of continuous DHT treatment could not be reversed. Since human studies have shown that hyperandrogenism is ameliorated by bariatric surgery24, our model sought to recreate these improved conditions. Previously, the DHT-treatment has only been done in chow-fed animals which has allowed for understanding the contribution of hyperandrogenism alone to the human phenotype. Our modified model utilized HFD to allow for these obesity-induced manifestations that may be more similar to the situation for many PCOS patients.

Metabolic improvements observed from VSG in the PCOS model included reduced food intake, body weight and adiposity, with improved fasting glucose and triglyceride levels. These results suggest that women with PCOS who undergo VSG will have significant metabolic improvements. There is no literature to date regarding women with PCOS undergoing VSG; nonetheless, several studies have shown similar metabolic impacts of RYGB and VSG on insulin sensitivity31–33 and lipids33, 34. Despite the awareness that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are key features of PCOS, the etiology and mechanisms of improvement are not fully understood.

While obesity is associated with PCOS and exacerbates many of its comorbidities, the etiology of the obesity observed in many PCOS patients is unclear. One hypothesis is that women with PCOS may have altered dietary consumption and food preferences35. Accurate human data are difficult to obtain due to reporting error (underestimation and change of diet knowing that they are being evaluated and recall bias). When given a choice of macronutrients, our PCOS animals did not differ from controls in a preference for fat, carbohydrate or protein, suggesting that elevated androgens are not sufficient to drive a significant change in preference for fat or carbohydrate. These results are consistent with one similar human study36. Interestingly, the PCOS animals consumed fewer kCal during this experiment in contrast to the remainder of the study. One potential explanation is that the change of diet was in and of itself a a stressor to which the PCOS animals had a more difficult time coping.

Women with PCOS have been shown to have altered stress responses37 and an association with psychosocial problems, including depression, anxiety, chronic stress and reduced quality of life38, 39. The mechanism underlying these associations is unknown. One explanation is that the psychological impairments are caused by the distress induced by PCOS-associated symptoms (e.g., obesity, hirsutism, infertility, etc.); another explanation is an organic cause, such as hyperandrogenism. While some studies have shown a correlation between androgen levels and anxiety40, others have not41. Our results support an organic contribution, as this model eliminates the confounders of psychosocial variables and demonstrates a clear relationship between hyperandrogenism and anxiety. Psychosocial contributions affecting women with PCOS, however, are not testable in animal models, and may also play a significant role.

Plasma glucocorticoid levels have been used as a biomarker of physiological and psychological stressors, as stressful stimuli cause an increase in activity in the HPA axis, leading to increased glucocorticoid secretionl42, 43. V-DHT animals had a reduced corticosterone response to a novel environment stress. Remarkably, all VSG animals had lower basal corticosterone levels, but there were no differences in basal or acute stressed ACTH levels. This implies that the decreased corticosterone levels are the result of a primary adrenal difference rather than differences at the level of the hypothalamus or pituitary. Since women with PCOS have demonstrated increased stress-induced HPA axis reactivity37, VSG may serve to ameliorate this exaggerated response. The lower corticosterone levels post-VSG may infer further metabolic benefit given that cortisol promotes central fat accumulation and insulin resistance44, 45.

Reproductive function was impaired in the DHT-treated animals, similar to women with PCOS and hyperandrogenemia. After resolution of the hyperandrogenemia and surgically-induced weight loss, the V-DHT animals slowly regained normal cyclicity; this is similar to humans post-bariatric surgery who regained normal menstrual patterns23, 24. They did not, however, regain normal reproductive function faster than sham animals, as hypothesized. The human literature regarding weight loss and reproductive function is variable; some report a weight loss of as little as 5% body weight improving menstrual cyclicity and ovulation rates46–48 and others report limited improvement49. One suggested mechanism for this variation is that hyperinsulinemia in women with obesity contributes to anovulation50, 51 and resumption of ovulation is mediated by reduced insulin resistance50, 52. Insulin signaling has a role in ovarian steroidogenesis, follicle development and granulosa cell proliferation51, 53, 54. Both obese and lean women with PCOS have greater insulin resistance than weight-matched controls55. This hypothesis is further supported by the evidence that metformin improves ovulation, as reported in a recent Cochrane review56.

Another consideration is that the animals remained on HFD through the entirety of the study. By post-operative week 4 (i.e., week 12 on HFD) even S-Control animals exhibited a decline in normal cyclicity. Little is understood about the effects of diet on fertility. One study suggests that dietary trans fatty acids increase the risk of ovulatory infertility57. The dietary intake of high levels of saturated fatty acids is positively associated with the development of insulin resistance58. Another study showed that female rats with HFD-induced obesity developed systemic insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and an extended estrous cycle with altered ovarian insulin signaling59.

Conclusions

There are a variety of treatments available for women with PCOS. Most of the treatments, however, are symptom-based and do not address the metabolic, behavioral and reproductive problems simultaneously. We have shown that VSG can improve many manifestations of PCOS in a comprehensive manner, including weight loss, glucose homeostasis, stress-induced behavior and menstrual regularity when the overriding hyperandrogenism is removed. Two reports in humans suggest that RYGB may ameliorate the symptoms of PCOS60, 61 and improve fertility61 These human studies as well as our rodent studies suggest that the amelioration of the PCOS symptoms are secondary to weight loss and improved glucose tolerance following bariatric surgery. Further investigation will be needed to understand the mechanisms involved and the effects of VSG in humans with PCOS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jose Berger, Alfor Lewis, Ken Parks, Kathi Smith and Mouhamadoul Toure for their surgical expertise.

Grants

The work of the laboratory is supported in part by NIH Awards DK56863, DK57900, U01CA141464, DK082480, MH069860, DK082480 and also work with Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Pfizer Inc. and Novo Nordisk A/S. BEG is also supported by NIH Award 1F32HD68103.

Disclosures:

RJS receives research support from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Novo Nordisk, Ablaris, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Zealand. RJS has served on scientific advisory boards for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Angiochem, Zealand, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis and Novo Nordisk. RJS is a paid speaker for Merck, Ethicon Endo-Surgery and Novo Nordisk.

Footnotes

Contribution Statement

IBR and BEG were responsible for executing and analyzing experiments. IBR, BEG and RJS were responsible for planning experiments, interpretation of data and literature and drafting of the manuscript. All authors approved of the final version for publication.

References

- 1.Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R, et al. Consensus on women's health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.024. e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Group REA-SPCW. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burghen GA, Givens JR, Kitabchi AE. Correlation of hyperandrogenism with hyperinsulinism in polycystic ovarian disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50(1):113–116. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-1-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrmann DA, Kasza K, Azziz R, Legro RS, Ghazzi MN. Effects of race and family history of type 2 diabetes on metabolic status of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(1):66–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Franca Neto AH, Rogatto S, Do Amorim MM, Tamanaha S, Aoki T, Aldrighi JM. Oncological repercussions of polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26(10):708–711. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.490607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbott EO, Guzick DS, Sutton-Tyrrell K, McHugh-Pemu KP, Zborowski JV, Remsberg KE, et al. Evidence for association between polycystic ovary syndrome and premature carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(11):2414–2421. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luque-Ramirez M, Mendieta-Azcona C, Alvarez-Blasco F, Escobar-Morreale HF. Androgen excess is associated with the increased carotid intima-media thickness observed in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3197–3203. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wild RA, Rizzo M, Clifton S, Carmina E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(3):1073–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.027. e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gambarin-Gelwan M, Kinkhabwala SV, Schiano TD, Bodian C, Yeh HC, Futterweit W. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(4):496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vgontzas AN, Legro RS, Bixler EO, Grayev A, Kales A, Chrousos GP. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):517–520. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jedel E, Waern M, Gustafson D, Landen M, Eriksson E, Holm G, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(2):450–456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerchner A, Lester W, Stuart SP, Dokras A. Risk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. Jama. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraschnewski JL, Boan J, Esposito J, Sherwood NE, Lehman EB, Kephart DK, et al. Long-term weight loss maintenance in the United States. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34(11):1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(5):579–584. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Kettel Khan L, Gillespie C, Serdula MK. Weight regain in U.S. adults who experienced substantial weight loss, 1999–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran LJ, Hutchison SK, Norman RJ, Teede HJ. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD007506. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007506.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bray GA. Lifestyle and pharmacological approaches to weight loss: efficacy and safety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S81–S88. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pontiroli AE, Morabito A. Long-term prevention of mortality in morbid obesity through bariatric surgery. a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials performed with gastric banding and gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):484–487. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d98cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashrafian H, Ahmed K, Rowland SP, Patel VM, Gooderham NJ, Holmes E, et al. Metabolic surgery and cancer: protective effects of bariatric procedures. Cancer. 2011;117(9):1788–1799. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batsis JA, Romero-Corral A, Collazo-Clavell ML, Sarr MG, Somers VK, Lopez-Jimenez F. Effect of bariatric surgery on the metabolic syndrome: a population-based, long-term controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(8):897–907. doi: 10.4065/83.8.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eid GM, Cottam DR, Velcu LM, Mattar SG, Korytkowski MT, Gosman G, et al. Effective treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(2):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escobar-Morreale HF, Botella-Carretero JI, Alvarez-Blasco F, Sancho J, San Millan JL. The polycystic ovary syndrome associated with morbid obesity may resolve after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6364–6369. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manneras L, Cajander S, Holmang A, Seleskovic Z, Lystig T, Lonn M, et al. A new rat model exhibiting both ovarian and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3781–3791. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Y, Johansson J, Shao R, Manneras L, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Billig H, et al. Hypothalamic neuroendocrine functions in rats with dihydrotestosterone-induced polycystic ovary syndrome: effects of low-frequency electro-acupuncture. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefater MA, Perez-Tilve D, Chambers AP, Wilson-Perez HE, Sandoval DA, Berger J, et al. Sleeve Gastrectomy Induces Loss of Weight and Fat Mass in Obese Rats, but Does Not Affect Leptin Sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2426–2436. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.059. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker JB, Arnold AP, Berkley KJ, Blaustein JD, Eckel LA, Hampson E, et al. Strategies and methods for research on sex differences in brain and behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146(4):1650–1673. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masszi G, Buday A, Novak A, Horvath EM, Tarszabo R, Sara L, et al. Altered insulin-induced relaxation of aortic rings in a dihydrotestosterone-induced rodent model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(2):573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson-Perez HE, Seeley RJ. The effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on a rat model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3700–3705. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbatini F, Rizzello M, Casella G, Alessandri G, Capoccia D, Leonetti F, et al. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding on type 2 diabetes. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(5):1005–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen B, Peters T, Devaux N, Kern B, Christoffel-Courtin C, et al. Improvement in glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):234–241. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ae32e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woelnerhanssen B, Peterli R, Steinert RE, Peters T, Borbely Y, Beglinger C. Effects of postbariatric surgery weight loss on adipokines and metabolic parameters: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy--a prospective randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(5):561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefater MA, Sandoval DA, Chambers AP, Wilson-Perez HE, Hofmann SM, Jandacek R, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in rats improves postprandial lipid clearance by reducing intestinal triglyceride secretion. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):939–949. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.008. e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holte J, Bergh T, Berne C, Wide L, Lithell H. Restored insulin sensitivity but persistently increased early insulin secretion after weight loss in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(9):2586–2593. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.9.7673399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altieri P, Cavazza C, Pasqui F, Morselli AM, Gambineri A, Pasquali R. Dietary habits and their relationship with hormones and metabolism in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78(1):52–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson S, Arck PC, Tan S, Hahn S, Mann K, Rifaie N, et al. Disturbed stress responses in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(5):727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, Wild R. Increased prevalence of anxiety symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.022. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barry JA, Kuczmierczyk AR, Hardiman PJ. Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2442–2451. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner CL, Primeau M, Ehrmann DA. Androgens and mood dysfunction in women: comparison of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome to healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):356–362. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127871.46309.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jedel E, Gustafson D, Waern M, Sverrisdottir YB, Landen M, Janson PO, et al. Sex steroids, insulin sensitivity and sympathetic nerve activity in relation to affective symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(10):1470–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adam EK, Kumari M. Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(10):1423–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen NT, Goldman CD, Ho HS, Gosselin RC, Singh A, Wolfe BM. Systemic stress response after laparoscopic and open gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(5):557–566. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01132-8. discussion 566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Black PH. The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response: Implications for atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome X. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(5):350–364. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Cacciari M, Pagotto U. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:111–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasquali R, Antenucci D, Casimirri F, Venturoli S, Paradisi R, Fabbri R, et al. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of obese amenorrheic hyperandrogenic women before and after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68(1):173–179. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huber-Buchholz MM, Carey DG, Norman RJ. Restoration of reproductive potential by lifestyle modification in obese polycystic ovary syndrome: role of insulin sensitivity and luteinizing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(4):1470–1474. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clark AM, Ledger W, Galletly C, Tomlinson L, Blaney F, Wang X, et al. Weight loss results in significant improvement in pregnancy and ovulation rates in anovulatory obese women. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(10):2705–2712. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, Norman RJ. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(2):812–819. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Pagotto U. The impact of obesity on reproduction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Bjog. 2006;113(10):1148–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willis D, Mason H, Gilling-Smith C, Franks S. Modulation by insulin of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone actions in human granulosa cells of normal and polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(1):302–309. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guzick DS, Wing R, Smith D, Berga SL, Winters SJ. Endocrine consequences of weight loss in obese, hyperandrogenic, anovulatory women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(4):598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adashi EY, Resnick CE, Payne DW, Rosenfeld RG, Matsumoto T, Hunter MK, et al. The mouse intraovarian insulin-like growth factor I system: departures from the rat paradigm. Endocrinology. 1997;138(9):3881–3890. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poretsky L, Cataldo NA, Rosenwaks Z, Giudice LC. The insulin-related ovarian regulatory system in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1999;20(4):535–582. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.4.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morales AJ, Laughlin GA, Butzow T, Maheshwari H, Baumann G, Yen SS. Insulin, somatotropic, and luteinizing hormone axes in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: common and distinct features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(8):2854–2864. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.8.8768842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang T, Lord JM, Norman RJ, Yasmin E, Balen AH. Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD003053. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003053.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner BA, Willett WC. Dietary fatty acid intakes and the risk of ovulatory infertility. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):231–237. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Storlien LH, Jenkins AB, Chisholm DJ, Pascoe WS, Khouri S, Kraegen EW. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats. Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes. 1991;40(2):280–289. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akamine EH, Marcal AC, Camporez JP, Hoshida MS, Caperuto LC, Bevilacqua E, et al. Obesity induced by high-fat diet promotes insulin resistance in the ovary. J Endocrinol. 2010;206(1):65–74. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomez-Meade CA, Lopez-Mitnik G, Messiah SE, Arheart KL, Carrillo A, de la Cruz-Munoz N. Cardiometabolic health among gastric bypass surgery patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome. World J Diabetes. 2013;4(3):64–69. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v4.i3.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jamal M, Gunay Y, Capper A, Eid A, Heitshusen D, Samuel I. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass ameliorates polycystic ovary syndrome and dramatically improves conception rates: a 9-year analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(4):440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]