Abstract

We examined parent emotion dysregulation as part of a model of family emotion-related processes and adolescent psychopathology. Participants were 80 parent–adolescent dyads (mean age = 13.6; 79 % African-American and 17 % Caucasian) with diverse family composition and socioeconomic status. Parent and adolescent dyads self-reported on their emotion regulation difficulties and adolescents reported on their perceptions of parent invalidation (i.e., punishment and neglect) of emotions and their own internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Results showed that parents who reported higher levels of emotion dysregulation tended to invalidate their adolescent’s emotional expressions more often, which in turn related to higher levels of adolescent emotion dysregulation. Additionally, adolescent-reported emotion dysregulation mediated the relation between parent invalidation of emotions and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Potential applied implications are discussed.

Keywords: Emotion dysregulation, Emotion socialization, Invalidation, Parenting, Externalizing, Internalizing

Introduction

Emotion regulation difficulties are associated with numerous clinical disorders and it has been posited that the development of psychopathology may stem from difficulties regulating emotions (Ehrenreich et al. 2009; Zeman et al. 2006). Associations between emotion dysregulation and externalizing behaviors have been reported in children (Morris et al. 2010; Valiente et al. 2007), and associations with internalizing problems have been shown in children and adolescents (Aldao et al. 2010; Neumann et al. 2010). Though empirical evidence to support the directionality of these paths is limited, a longitudinal study showed that emotion regulation predicted emotional adjustment (e.g., lower anxiety and negative affect) but emotional adjustment did not predict emotion regulation (Berking et al. 2008).

Numerous aspects of the family environment are thought to contribute to the development of youth emotion regulation capabilities (see Morris et al. 2007 for a review). Some of these factors include the emotional climate of the family, observations of how family members handle emotions, and emotion-related parenting practices (Eisenberg et al. 1999; Morris et al. 2007). With regard to emotion-related parenting practices, the ways parents respond to their children’s emotional experiences seem to be associated with youth emotion regulation competencies (Eisenberg et al. 1998; Gottman et al. 1996; Morris et al. 2007). Parent responses to children’s emotions that are supportive provide a context in which youth (a) feel comforted, (b) develop perceptions that their parents are available to help them cope with distress, and (c) learn how to understand, express, and regulate negative emotional experiences. Invalidating parent reactions on the other hand can heighten youth’s distress and teach them that emotions are unacceptable and cannot be tolerated by their parents. These parent reactions likely limit the opportunities that youths have to learn effective ways of dealing with negative emotions (Jones et al. 2002). Parent neglect and punishment of youth emotions are forms of emotional invalidation (Linehan 1993). Neglect of emotions may model avoidance of emotional expression and punishment of emotions may send the message that emotions should not be discussed or expressed, and encourage inhibition of emotions (Gottman et al. 1997).

Prominent models of emotion socialization posit that youth emotion regulation skills mediate the relation between emotion-related parenting practices and youth adjustment (Eisenberg et al. 1998; Gottman et al. 1997; Morris et al. 2007). Relatively few studies, however, have directly examined this mediational hypothesis to predict youth internalizing and externalizing problems despite support for direct pathways in a number of studies. Studies of potentially related constructs provide initial support. For example, young children’s emotion regulation mediated the relation between mothers’ expression of positive emotions and children’s externalizing behaviors (Eisenberg et al. 2003). Additionally, studies have found that emotion regulation mediates the relation between retrospective reports of parenting practices and maladaptive behaviors (i.e., self-harm and disordering eating) in early adulthood (Buckholdt et al. 2009, 2010).

Parent Emotion Regulation

To further investigate hypotheses put forth in emotion socialization theoretical frameworks, research is also needed to examine antecedents of emotion-related parenting practices (Kovan et al. 2009). Parental emotion regulation may be particularly important to examine given that difficulties or deficiencies in regulation skills (e.g., avoidance of emotions and emotionally salient events, the inability to manage one’s own emotions using adaptive strategies) could adversely influence or limit parent responses to youth emotions. Parental emotion regulation difficulties could hinder responsiveness to the emotions of their adolescents, particularly given that adolescents may experience intense and fluctuating emotions that may tax parents’ emotion-related skills (Larson et al. 2002; see Klimes-Dougan and Zeman 2007 for a discussion). Distinct but related constructs have been researched, including parenting empathy and empathic overarousal/personal distress (Davis et al. 1994; Batson et al. 1983). This line of research suggests that individuals high in empathic arousal often find it difficult to respond appropriately or remain in situations involving empathy due to high emotional arousal, and respond to other people’s distress with an escape/avoidant response (Batson et al.). Similarly, if parents have emotion regulation deficits, they may find it difficult to engage in emotionally-charged discussions with their adolescent due to high emotional arousal. Interestingly, the most widely used measure of parental responses to children’s emotions includes a subscale reflecting parental distress reactions (Fabes et al. 1990). This inclusion suggests that more research is needed to understand the role of parental emotional distress in understanding how parents respond to youth emotions.

Morris et al. (2007) reviewed numerous studies that examined direct associations between parent responses to emotions, emotion regulation, and adjustment. In addition, Morris et al. (2007) expanded on previous conceptual models to include parent characteristics as a potential contributor to the family context in which emotion socialization occurs. Evidence directly linking parent emotion regulation to parenting practices is lacking but parental negative expressivity, modeling of intense emotional reactions, and problematic responses to conflict may represent forms of dysregulation and influence emotional functioning in the family. The model proposed by Morris et al. (2007) suggests that parent characteristics (including reactivity and parent emotion regulation) contribute to the family environment (including parenting practices and observation of parental emotional reactions).

It has not been established whether parents who have difficulty regulating emotions also have adolescents who have emotion regulation difficulties. In a review, Yap et al. (2007) identified parent emotion regulation as a possible contributing factor to both adolescent emotion regulation and adolescent depression. Factors such as parental negative affect, conflict resolution, and parent emotion management in the context of family stressors have been linked to youth difficulties in similar areas (Yap et al.). Given the scarcity of studies examining the transmission of emotion regulation difficulties from parent to adolescent, not much is known about mechanisms that would explain this relation. One possibility is that emotion regulation difficulties could be transferred through parenting practices. Notably, Valiente et al. (2007) found that parent and child effortful control were associated through parenting practices. This provides some preliminary support for the association posited in the current study as effortful control can be considered to be related to, or a component of, emotion regulation. Likewise, other potentially related factors, such as parental psychopathology, have been associated with parenting behaviors (Pelaez et al. 2008) and children’s emotion regulation difficulties (Silk et al. 2006). Parents who have difficulty regulating emotions may avoid emotionally salient events—including interactions with their adolescents about their emotional experiences. Avoidance could occur by ignoring (i.e., neglecting) or actively discouraging (i.e., punishing) an adolescent’s emotions. Invalidating responses (i.e., punishment and neglect of emotions) to adolescent emotional experiences and expressions may be important parenting practices to examine in the context of parent emotion regulation difficulties given that these responses could reduce exposure to adolescent emotions in the moment and potentially discourage future expressions (or be maintained by this expectation). A transactional cycle of parent dysregulation, invalidation, and youth dysregulation is quite possible in this context.

From a methodological perspective, there are several ways to build on prior emotional socialization research. Much of the research supporting emotion socialization processes have focused on children. Recently, there has been a call to expand these lines of inquiry into adolescence (Klimes-Dougan and Zeman 2007). This is not surprising as there are numerous reasons why emotion-related processes—and emotion regulation difficulties in particular—may be important during this developmental period. For example, compared to other developmental periods, adolescents are thought to experience more negative and less positive emotions (Larson and Lampman-Petraitis 1989; Larsonet al. 2002). Although it is not universally accepted, it is also suggested that adolescents may have more frequently changing, extreme, and intense emotions (see Arnett 1999). In addition, adolescents face a range of interpersonal challenges, including new social situations (e.g., romantic relationships), and this can place a high demand on their ability to regulate emotions. Parents continue to play a role in helping adolescents manage the intense emotional experiences characteristic of this developmental period (Klimes-Dougan and Zeman). Another way to extend prior emotional socialization research is to conduct studies with more diverse samples (Cole and Tan 2007; Dunsmore and Halberstadt 2009). The large majority of research in this area has been conducted with Caucasian middle class families. Thus, conducting research with diverse samples especially in terms of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status would provide an opportunity to consider similarities and differences of emotion socialization processes across different cultural contexts.

The Present Study

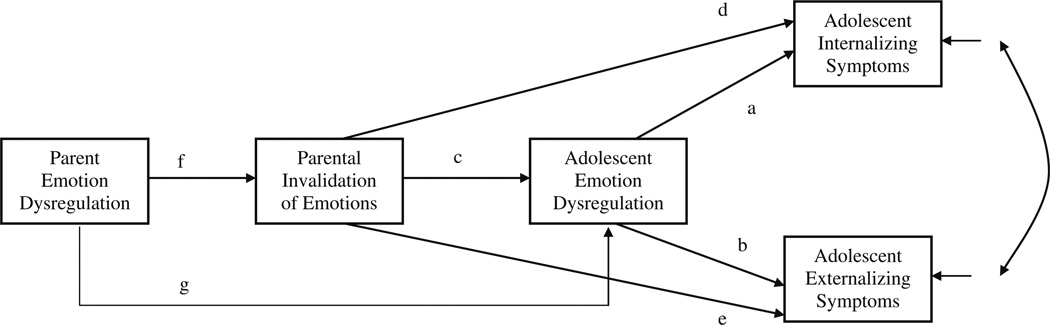

This study empirically examines a model of family emotion-related processes. The conceptual model tested in the present study is shown in Fig. 1. As shown, (a) parent invalidation of emotions is hypothesized to be associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms both directly and indirectly through adolescent emotion regulation difficulties, and (b) parent emotion regulation difficulties are hypothesized to be related to adolescent emotion regulation difficulties through parent invalidation of adolescent emotions. Specific hypotheses for each of the paths are: adolescent self-reported emotion dysregulation will be associated with higher levels of adolescent self-reported internalizing (path a) and externalizing (path b) symptoms, more frequent adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions will be associated with more adolescent self-reported emotion dysregulation (path c), adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions will be associated with higher levels of adolescent-reported internalizing (path d) and externalizing (path e) symptoms, parent self-reported emotion dysregulation will predict higher levels of adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions (path f), and higher levels of adolescent self-reported emotion dysregulation (path g). The major contributions of this study are the investigation of intergeneration transmission of emotion dysregulation and the examination of mediational pathways to youth adjustment.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Method

Participants

There were 107 adolescents and 89 parents who provided useable data for the study. Of those, 89 adolescents had scores for all of the adolescent-reported measures and 80 parents completed the parent-report of emotion dysregulation. Data from 80 participant dyads (i.e., parent and adolescent) with data on all measures were used in the final analyses and the following information pertains to these participants. Participants were adolescents (ages 12–18; mean age = 13.6; SD age = 1.14) and one of their parents who took part in a study examining emotion-related family processes. The majority of participants (79 %) self-identified as African-American; 17 % self-identified as Caucasian, 3 % Biracial, and 1 % Asian. Approximately 93 % of the parents were a female caregiver (86 % biological mother, 4 % adoptive mother, 3 % step-mother, 1 % grandmother) to the adolescent. There was also diversity in family composition as 43 % reported living with both biological parents, 35 % living with biological mother only, 11 % with mother and step-father, and 11 % in other family compositions. Participants reported similarly diverse indicators of socioeconomic status with 12.5 % of mothers holding a graduate degree, 22.5 % with a 2- or 4-year college degree, 15 % with some college or vocational training, 16 % with a high school diploma only, and 6 % did not graduate high school.

Procedures

Flyers were distributed at three middle schools and eight community centers in a large southern city in the United States. Families who were interested in participating in the study either called to schedule an appointment for the assessment or returned a portion of the flyer indicating that both the adolescent and parent were willing to participate. Parental consent and adolescent assent were required for participation. Adolescents completed the questionnaire battery during an assessment session conducted by trained graduate and undergraduate students. Parents were given the option to complete the questionnaires during the assessment session in a separate room from their adolescent or to complete the measures at home. Parents and adolescents were given $15 each for their participation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Emotion Regulation Difficulties

Parents and adolescents completed the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer 2004). The DERS is a 36-item self-report measure which assesses six components of emotion regulation (i.e., clarity, awareness, acceptance, goals, strategies, and impulse control). Items measure how often the participant engages in different behaviors or has certain feelings or thoughts (e.g., “When I am upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way”). Participants respond on a scale of 1–5 where 1 is “almost never (0–10 %),” 2 is sometimes (11–35 %), 3 is “about half the time (36–65 %),” 4 is “most of the time (66–90 %),” and 5 is almost always (91–100 %). The average of all items was used and higher scores reflect more emotion regulation difficulties. The DERS had high internal consistency for both adolescent (α = .92) and parent (α = .94) self-reports. This is comparable to previous studies in adolescents (α = .93; Weinberg and Klonsky 2009) and adults (α = .93; Gratz and Roemer). The DERS was found to have adequate construct and predictive validity (Gratz and Roemer).

Invalidation of Adolescent Emotions

Adolescents completed the Emotion Socialization scale of the Emotions as a Child Scales (EAC; O’Neal and Magai 2005) which assesses five parent responses (i.e., punish, reward, neglect, override, and magnify) across emotion subscales. The present study uses items reflecting parent neglect and punishment of sadness, anger, and shame. Adolescents reported “how often their primary caregiver responds in the following ways” on 5 point scale (1 = never; 5 = very often). The average of 18 items (three items for each of the three emotions for parent responses of neglect and punishment) was calculated to create a global invalidation score. A higher score reflects more invalidation of emotions. The global invalidation subscale was shown to have adequate internal consistency (α = .87). This is slightly higher than previous studies in which the global punishment and neglect scales included sadness, anger, shame, and fear (α = .72 and .75, respectively; O’Neal and Magai). The EAC was reported to have some evidence of validity among adult samples and has been used with racially diverse adolescent samples (O’Neal and Magai).

Adolescent Symptoms of Psychopathology

Adolescents completed the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach 1991) a 112-item, well-validated, and widely used measure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Participants rated items reflecting behaviors that occurred over the last 6 months on a 3 point scale (0 = not true to 2 = very true/often true). T-scores were calculated with higher scores reflecting more internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The internalizing (α = .88) and externalizing (α = .90) scales were shown to have adequate internal consistency.

Results

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and ranges) and zero-order correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Findings indicated that there was a significant positive association between parent and adolescent emotion dysregulation (r = .26; p < .05). Parents who reported more difficulty regulating emotions tended to have adolescents who also reported more difficulty regulating emotions. There were also significant positive associations between adolescent-reported parental invalidation of emotions and adolescent self-reported internalizing (r = .39, p < .001) and externalizing (r = .26; p < .05) symptoms. Parent emotion dysregulation was not significantly associated with adolescent internalizing or externalizing symptoms. Correlations were also computed to examine whether sex (point-biserial correlation) and age were related to the primary study variables. Findings indicated that the sex and age of the adolescent were not significantly related to any variables in the hypothesized model.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among study measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent emotion regulation difficulties | |||||

| 2. Parent invalidation of emotions | .40*** | ||||

| 3. Adolescent emotion regulation difficulties | .26* | .42*** | |||

| 4. Adolescent internalizing symptoms† | .18 | .39*** | .60*** | ||

| 5. Adolescent externalizing symptoms† | .11 | .26* | .64*** | .61*** | |

| Mean | 1.94 | 1.77 | 2.26 | 54.11 | 55.13 |

| SD | .58 | .54 | .61 | 9.31 | 9.98 |

| Range (min) | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.25 | 35.00 | 29.00 |

| Range (max) | 3.56 | 3.76 | 3.75 | 80.00 | 78.00 |

N = 80

p < .05,

p < .001

T-scores were used for the Youth Self Report

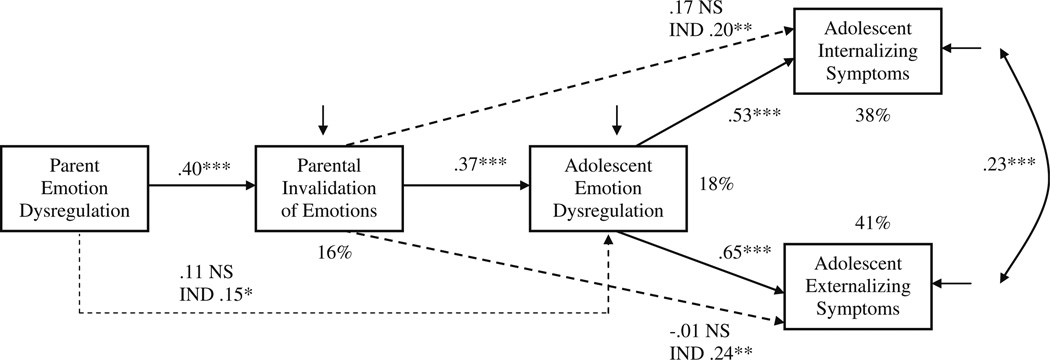

The conceptual model was estimated using MPlus Version 3.13 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006). Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was employed. Hypotheses related to indirect effects were tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping. Findings indicated that the model provided a good fit to the data [χ2 (2, n = 80) = .49, p = .78; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .02]. This model explained 16 % of the variance in parent invalidation of emotions, 18 % of the variance in adolescent difficulty regulating emotions, 38 % of the variance in internalizing symptoms, and 41 % of the variance in externalizing symptoms. With regard to specific parameters (see Fig. 2), parent self-reported emotion dysregulation predicted adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions (β = .40, p < .001; path f). Parents who reported more difficulty regulating their own emotions invalidated their adolescent’s expression of emotions more often. Adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions, in turn, predicted adolescent emotion dysregulation (β = .37, p < .01; path c). In other words, adolescents who perceived emotional invalidation by parents were more likely to have difficulty regulating emotions. To test whether parental invalidation of emotions mediated the relation between parent and adolescent emotion dysregulation, the indirect effect was examined. Findings indicated that there was a significant indirect effect between parent and adolescent self-reported emotion dysregulation (indirect effect = .15, p < .05; path g) and the association between parent and adolescent emotion dysregulation was non-significant (β = .11, p = NS) with the inclusion of adolescent-reported parental invalidation of emotions as a mediator. This finding indicates that adolescent-reported parental invalidation of emotions might be a mechanism through which parent and adolescent emotion regulation difficulties could be transferred from parent to adolescent.

Fig. 2.

Results of the proposed model. NS not significant, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. IND indirect effects. χ2 (2, n = 80) = .49, p = .78; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .02

Adolescent self-reported emotion dysregulation predicted adolescent self-reported internalizing (β = .53, p < .001; path a) and externalizing (β = .65, p < .001; path b) symptoms. In other words, adolescents who reported more difficulties regulating emotions endorsed higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Indirect effects were examined to test whether adolescent emotion dysregulation mediated the relations between adolescent reported parental invalidation of emotions and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Findings indicated that there were significant indirect effects between adolescent-reported parental invalidation of emotions and internalizing (indirect effect = .20, p < .01; path d) and externalizing (indirect effect = .24; p < .01; path e) symptoms. In addition, the associations between parental invalidation of emotions and internalizing (β = .17; p = NS) and externalizing (β = −.01; p = NS) symptoms were non-significant with the inclusion of adolescent emotion dysregulation as a mediator. These findings indicate that adolescent emotion dysregulation might be a mechanism through which adolescent-reported parent invalidation of emotions contributes to adolescent-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Discussion

Heuristic models of emotion socialization processes provide a comprehensive picture of numerous factors that may contribute to youth outcomes. However, few studies have empirically examined the complex paths proposed by these models. Additionally, emotionally-related parenting behaviors are often used as a starting point for examining these processes while potential explanations for these parenting behaviors are largely neglected. The findings from the current study suggest that parents’ own emotion dysregulation is associated with parent invalidation of emotions, which in turn is related to adolescent emotion dysregulation. The findings also suggest that the association between parent invalidation of emotions and adolescent internalizing/externalizing symptoms is due, at least in part; to the difficulties adolescents may have regulating emotions. This study provides initial support for the model of emotion-related family processes presented here; a model that builds on theoretical and empirical work by many others. Although encouraging, results from this study should be viewed with caution in light of several limitations (see below).

There are a number of reasons why parent invalidation of emotions might contribute to adolescents’ lack of adaptive strategies and skills for regulating emotion, and in turn, contribute to adolescent emotional and behavioral problems. With regard to internalizing symptoms, insufficient skills and low self-efficacy to cope with negative emotions may contribute to the persistence of sad feelings and subsequent feelings of depression, anxiety and the tendency to withdraw from others. Likewise, adolescents may not seek support from a parent if their emotions have been invalidated in the past. With regard to externalizing symptoms, insufficient emotion regulation skills could be due to under-regulation of emotions, such as impulsivity when experiencing negative emotion. This impulsivity could contribute to rule-breaking and aggressive behavior. Consistent with previous longitudinal research linking anger dysregulation to later externalizing problems in young children (Morris et al. 2010), we found that adolescents who reported more emotion regulation difficulties also endorsed more externalizing behaviors, such as rule-breaking and aggressive behavior. It is also possible that adolescents “act out” in order to solicit attention from their parent to their emotions, especially if they are upset about a lack of attention and have not been able to learn effective strategies for coping with emotional experiences on their own.

This study builds on existing knowledge by expanding the model to include parent emotion regulation difficulties. As previously noted, recent conceptual models include parental emotion regulation capabilities as a potential factor that could influence parenting practices, youth emotion regulation, and youth psychological adjustment (Morris et al. 2007; Yap et al. 2007). The empirical examination of parent emotion regulation in this context is an important contribution of this study. In line with this inclusion, we found support for the intergenerational transmission of emotion regulation difficulties (e.g., more parent emotion dysregulation was associated with more adolescent emotion dysregulation) and identified parent invalidation of emotions as a possible mechanism through which emotion regulation difficulties could potentially be passed from parent to adolescent. Parents who have limited skills for dealing with emotions (e.g., limited emotion knowledge, access to regulatory strategies, impulse control) may not know how to be helpful or they may be overwhelmed by their adolescent’s emotional experiences. The parent may invalidate their adolescent’s emotions and thus deprive the adolescent of the opportunities to learn ways to manage emotions. Parent invalidation could model avoidance and give the impression (directly using punishment or indirectly using neglect) that emotions are hard to deal with and perhaps should not be expressed or that they cannot be modified.

Together the findings from this study make a number of contributions to the literature. First, we found support for direct and indirect relations between parent responses to emotions, youth emotion regulation difficulties, and youth psychological adjustment. Second, this study addressed the need to identify factors that influence emotion-related parenting practices. Specifically, we found that parental difficulty regulating emotions may be transferred to adolescents via parent invalidation of emotions. Third, this study addressed the need for more research on emotion-related processes during adolescence. Although the findings are consistent with previous research elucidating emotion socialization processes during childhood, we expanded these findings into adolescence. Finally, the sample included a large percentage of African-American adolescents. This is important given the relatively small number of studies on emotion socialization processes that have been conducted with youth from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (Cole and Tan 2007). It is notable that findings using this sample were consistent with prominent models of emotion socialization. Future research should directly examine both similarities and differences in emotion socialization processes among youth from different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Our results could have several important applied implications, especially if the findings are replicated with a clinical sample. Our findings are consistent with interventions that target parenting skills and adolescent emotion regulation skills (see Ehrenreich et al. 2009 and Suveg et al. 2006) or that foster the parent–child relationship while teaching parenting skills (e.g., Zisser and Eyberg 2010). In addition, parent emotion regulation skills may be an important intervention target as well. Our study also highlights that there are complex associations which may indicate a need to target multiple factors in order to achieve and maintain improvement in adolescent emotional and behavioral functioning.

Some treatments view parenting practices as an adjunctive target to child-focused intervention, while potentially ignoring the factors that contribute to parenting practices. As noted by Kazdin and Weisz (1998), challenges to treatment may occur when parents are involved in treatment for the purposes of addressing adolescent problems while problematic parental functioning is not addressed. One possible reason why interventions that target parenting behavior may not have their desired effect is that parents’ own emotion-related difficulties may make it difficult to engage in ideal responses to their adolescent’s emotion-related experiences. Parents who lack sufficient skills to cope with their own emotions might invalidate the emotions of their adolescent or be unable to teach their adolescent coping skills that they themselves do not possess. Building on and extending beyond the present study, it may be important to develop and test emotion-focused family interventions that teach parents and youths skills for managing emotions and reinforce skill development and utilization by fostering supportive emotion-focused parenting practices and encouraging parental modeling of learned skills. As these factors relate to youth psychopathology (and likely parent psychopathology), targeting them has the potential to enhance the efficacy of current interventions. By targeting parent and youth emotional and behavioral dysregulation, transactional patterns between these factors can be addressed. In addition to teaching emotion regulation skills and emotion coaching parenting practices, mindful parenting may be beneficial for fostering parent–child relationships during adolescence using skills that are likely to validate the emotional experiences of youths (See Duncan et al. 2009; Dumas 2005).

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of the current study should be noted. The study is cross-sectional and thus longitudinal research is needed to further verify the direction of the hypothesized relations. Longitudinal designs can help us to better identify bidirectional patterns in parent and adolescent responses to one another. Initial work in this area has identified types of adolescent responses and how those responses are associated with parenting practices (Parra et al. 2010). Better understanding how adolescent emotional and behavioral dysregulation affects parenting will be an important avenue for future study. Another limitation is the small sample size. In addition, our study specifically requested participation from the primary caregiver, which often was the mother; however, future studies could target participation from both parents. In doing so, more could be learned about differences in parental emotion regulation competencies and the potential influence of one parent on another. Also, while youth perceptions of their parents’ responses to their emotions have been suggested to be at least as valuable as parents’ actual responses and parental reports of their own responses may be influenced by a tendency to report what they think they should do rather than what they (parents) actually do (Klimes-Dougan and Zeman 2007; O’Neal and Magai 2005), observations of family interactions would allow for coding of some of the components assessed in this model. Further study is warranted in order to determine whether adolescent perceptions match up with parent or observer reports and what additional information the discrepancies in these reports might add to our understanding of these processes.

As suggested by heuristic models and reviews of the literature on emotion socialization processes, numerous factors contribute to emotion socialization and youth outcomes. A main goal of this study was to take an important step at addressing the relative scarcity of empirical research examining parent emotion-related factors in models of emotion socialization processes. More remains to be done. For example, Morris et al. (2007) suggest that additional parent characteristics such as emotional reactivity may be predictors of parenting practices and that parent emotion regulation may influence factors other than parenting practices, such as the emotional climate of the family. Additional factors such as parenting stress may also be important to consider. For example, parents who experience more stressful events (e.g., due to financial strain or work-related stress) could have more demands placed on their ability to handle emotions. These demands could increase the frequency to which they would invalidate their adolescent’s emotional experiences. Likewise, factors such as the number of children a parent has or lack of social support could contribute to parent invalidation. Parent emotion regulation difficulties also may predict other parenting practices, such as facilitating their adolescent’s avoidance of emotion eliciting situations (e.g., taking the adolescent out of situations that are upsetting). Positive parenting practices (e.g., emotional encouragement), parent responses in the context of other emotions (e.g., joy and pride), and parental ability to regulate positive emotions could also be important to consider. For example, parents’ positive responses may provide a buffer against the effects of times when they have not been available or responsive.

Contributor Information

Kelly E. Buckholdt, Email: kbckhldt@memphis.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38157, USA.

Gilbert R. Parra, Department of Psychology, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA

Lisa Jobe-Shields, Department of Psychology, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38157, USA.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist. 1999;54:317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, O’Quin K, Fultz J, Vanderplas M, Isen AM. Influence of self-reported distress and empathy on egoistic versus altruistic motivation to help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:706–718. [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Orth U, Wupperman P, Meier L, Caspar F. Prospective effects of emotion-regulation skills on emotional adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:485–494. doi: 10.1037/a0013589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholdt K, Parra G, Jobe-Shields L. Emotion regulation as a mediator of the relation between emotion socialization and deliberate self-harm. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:482–490. doi: 10.1037/a0016735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholdt K, Parra G, Jobe-Shields L. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism through which parental magnification of sadness increases risk for binge eating and limited control of eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Tan PZ. Emotion socialization from a cultural perspective. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 516–542. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Luce C, Kraus SJ. The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:369–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE. Mindfulness-based parent training: Strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:779–791. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Halberstadt AG. The dynamic cultural context of emotion socialization. In: Mancini JA, Roberto KA, editors. Pathways of human development: Explorations of change. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2009. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich J, Goldstein C, Wright L, Barlow D. Development of a unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in youth. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2009;31:20–37. doi: 10.1080/07317100802701228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Morris AS, Fabes RA, Cumberland A, Reiser M, et al. Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children’s regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Bernzweig J. The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale: Procedures and scoring. Arizona State University; 1990. Available from authors. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, MacKinnon DP. Parents’ reactions to elementary school children’s negative emotions: Relations to social and emotional functioning at school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Weisz J. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Zeman J. Introduction to the special issue of social development: Emotion socialization in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2007;16:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kovan N, Chung A, Sroufe L. The intergenerational continuity of observed early parenting: A prospective, longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1205–1213. doi: 10.1037/a0016542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Lampman-Petraitis C. Daily emotional states as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development. 1989;60:1250–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Moneta G, Richards M, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73:1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A, Silk J, Steinberg L, Terranova A, Kithakye M. Concurrent and longitudinal links between children’s externalizing behavior in school and observed anger regulation in the mother–child dyad. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann A, van Lier P, Gratz K, Koot H. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Assessment. 2010;17:138–149. doi: 10.1177/1073191109349579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal CR, Magai C. Do parents respond in different ways when children feel different emotions? The emotional context of parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:467–487. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra GR, Olsen JP, Buckholdt KE, Jobe-Shields LE, Davis GL. A pilot study of the development of a measure assessing adolescent reactions in the context of emotion socialization. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:596–606. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez M, Field T, Pickens J, Hart S. Disengaged and authoritarian parenting behavior of depressed mothers with their toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk J, Shaw D, Skuban E, Oland A, Kovacs M. Emotion regulation strategies in offspring of childhood-onset depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Kendall PC, Comer JS, Robin J. Emotion-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth: a multiple-baseline evaluation. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2006;36:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Reiser M. Pathways to problem behaviors: Chaotic homes, parent and child effortful control, and parenting. Social Development. 2007;16:249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Klonsky E. Measurement of emotion dysregulation in adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:616–621. doi: 10.1037/a0016669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap M, Allen N, Sheeber L. Using an emotion regulation framework to understand the role of temperament and family processes in risk for adolescent depressive disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:180–196. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Stegall S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:155–168. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisser A, Eyberg SM. Treating oppositional behavior in children using parent–child interaction therapy. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2010. pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]