Abstract

A 12-step synthesis of kingianin A, an inhibitor of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL, is based on a radical cation Diels Alder reaction (RCDA). This approach is thought to be biomimetic. The use of a tether in the key RCDA step controls the regiochemistry of the cycloaddition, leading to the desired core structure and a separable diastereomer.

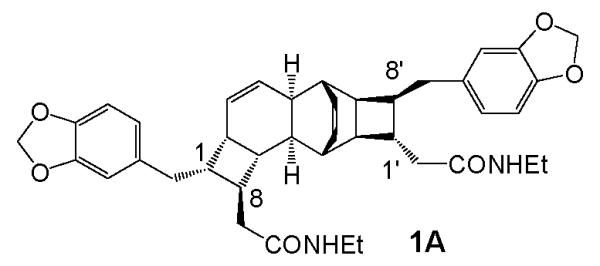

Containing a unique pentacyclic scaffold, the kingianins (e. g. (−)-kingianin A, 1A, Figure 1)1 are the structurally most complex members of a class of natural products believed to arise from conjugated polyketide polyenes by one or more non-enzymatic pericyclic processes. 2 They are reported to have low- to midmicromolar binding to the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL.1a The antiapoptotic Bcl proteins are considered to be valid drug targets for the treatment of cancer, particularly lymphomas, leukemias, and small cell lung cancers.3,4

Figure 1.

(−)-Kingianin A

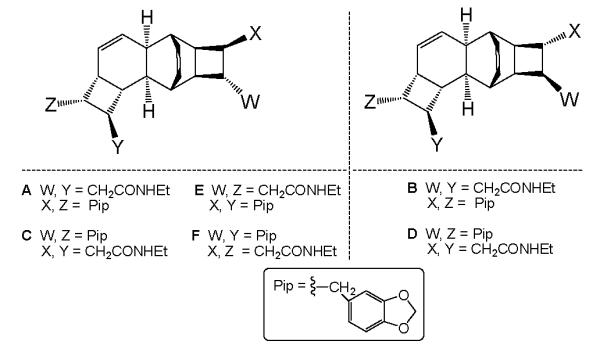

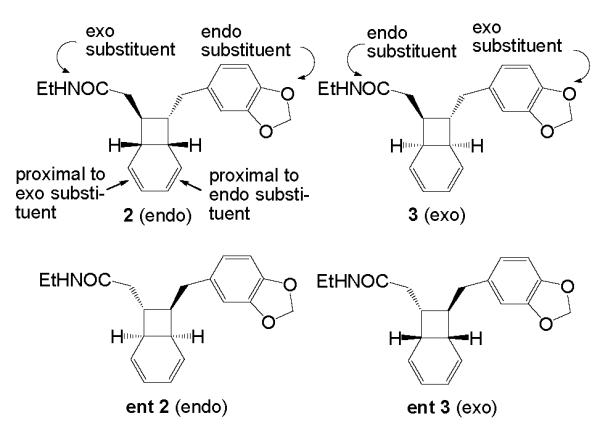

Each of the kingianins A-F (1, Figure 2) appears to be a Diels Alder adduct derived from two molecules of the purported biogenetic precursors: the enantiomers of endo5 amide 2 and those of its exo isomer 3 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Kingianins A-F

Figure 3.

Pre-kingianin A and its exo isomer

The synthesis of a mixture of the two racemic bicyclooctadienes 2 and 3 by the now classical Stille coupling/electrocyclization cascade method 6 , 7 and the separation of the two racemic compounds were reported by Moses et al.8 These authors dubbed isomer 2 “prekingianin A.” (−)-Kingianin A is the homodimer of monomer 2; kingianin D is the heterodimer of monomer 2 and monomer ent 2 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Derivation of Kingianins A-F from Pre-kingianin A 2 and its exo isomer 3

| kingianin | dienophile | diene |

|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 2 |

| B | 2 | ent 3 |

| C | 2 | 3 |

| D | 2 | ent 2 |

| E | 3 | 2 |

| F | 3 | 3 |

Not surprisingly, Moses and coworkers could not induce cyclohexadiene 2 or 3 (or a mixture of isomers 2 and 3) to provide kingianins under thermal conditions. The Diels Alder dimerization of unactivated cyclohexadienes does not take place at ambient temperatures and therefore does not occur in nonenzymatic transformations in plants.

We suggest that the biogenetic Diels Alder addition proceeds by a cation radical-mediated reaction (perhaps initiated photochemically).9 In support of this premise, we have pursued what we believe to be a biomimetic synthesis of kingianin A. Although the radical cation Diels Alder reaction (RCDA) has been known for 30 years, it has not previously been applied in the synthesis of complex natural product structures.10

The RCDA reaction of pre-kingianin A (2) is expected to be subject to certain regio- and steroselective influences. We know, for example, that the RCDA reaction prefers to proceed through an endo transition state11 and we would expect the monomers to approach each other from the less hindered face of each diene. Indeed, all of the naturally occurring kingianins have stereochemistry that is derived from an endo transition state corresponding to this direction of approach.

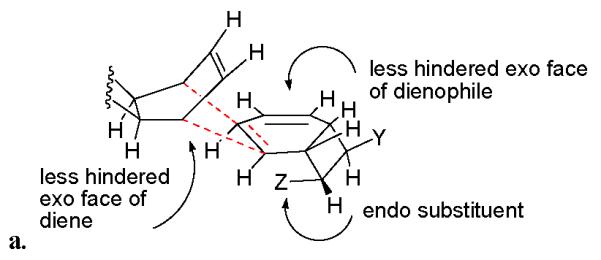

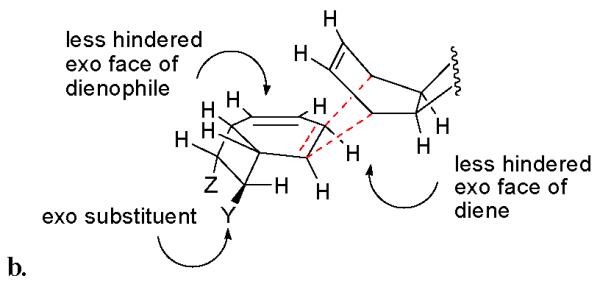

Furthermore, each of the natural products isolated corresponds to a cycloaddition in which the dienophilic olefinic bond is the one proximal to the exo substituent on the cyclobutane ring (see Figure 3). Consequently, in all of the kingianins, the C-8 substituent is exo with respect to the adjacent bicyclic system and the C-1 substituent is endo to this system (see Figure 2). We believe that this pathway selection follows from a second steric factor that develops in the endo transition state when the dienophilic olefin is proximal to the endo substitutent (see interaction in Figure 4a). Thus, the cyclobutane ring prevents addition to the dienophile from the endo (hindered) face and the endo substituent prevents addition to the double bond nearer to it from the exo face. Consequently the reaction proceeds through a transition state resembling that shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

a. Disfavored endo transition state for RCDA. The approach is from the less hindered face of the diene to the less hindered face of the dienophile. The dienophilic olefin is proximal to the endo substituent.

Figure 4.

b. Favored endo transition state for RCDA. The approach is from the less hindered face of the diene to the less hindered face of the dienophile. The dienophilic olefin is proximal to the exo substituent.

Because the RCDA of pre-kingianin A is subject to the stereochemical limitations described above, a single enantiomer is expected to undergo the RCDA dimerization to give a single enantiomer of kingianin A (i.e. enantiomer 2 as shown in Figure 2 should give (−)-kingianin A, 1A as shown in Figure 1). However, racemic pre-kingianin A (2) should give two products, racemic kingianin A (1A) and racemic kingianin D (1D). Therefore the isolation of kingianin A at the end of the synthesis requires either an asymmetric synthesis of prekingianin A (or a synthetic equivalent)12 or a practical method for the separation of kingianins A and D (or their synthetic equivalents).

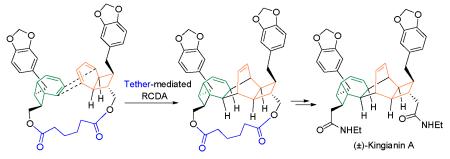

Here we report a solution to the construction problems described above: (1) the successful application of the RCDA to the synthesis of the kingianin core, and (2) the development of an intramolecular RCDA that affords separable diastereomers of the homodimeric and heterodimeric RCDA products. In addition, we describe the conversion of one of these diastereomers to kingianin A.

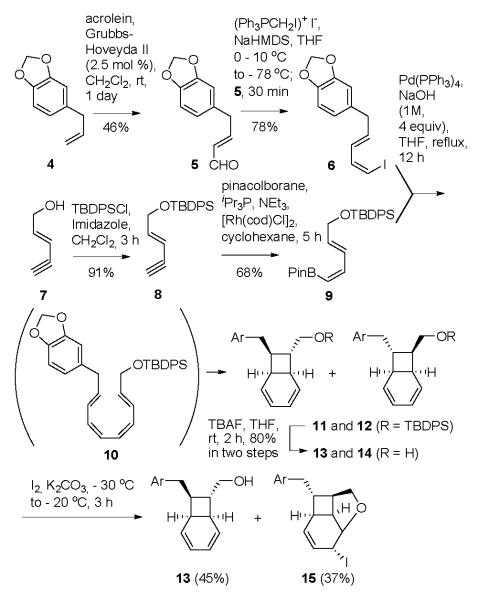

Our plan was to test the RCDA dimerization of a derivative of alcohol 13. Therefore we set out to obtain a mixture of the [4.2.0]-bicyclooctadiene 13 and its isomer 14 by the proven coupling / tandem electrocyclization strategy (Scheme 1) and then to remove the undesired 14 by selective iodoetherification 13 and simple chromatography. Because of the toxicity issues that accompany working with tin reagents, we sought an alternative to the Stille reaction which has generally been used in the coupling electrocyclization cascade. We are pleased to report that the Suzuki reaction of the known pinacolborane 914 is actually superior in this context.

Scheme 1.

Tandem Suzuki-Coupling, 8π, 6π Electrocyclization Cascade

The 5-step, easy-to-run synthesis of the desired alcohol 13 is shown in Scheme 1. Cross metathesis of safrole (4) with acrolein gave the known aldehyde 5. Stork-Zhao olefination provided the (E, Z)-iododiene 6. The required vinyl boronic ester 9 was prepared in two steps as described in the literature14 and coupled with iododiene 6 under Suzuki conditions. The expected mixture of bicyclo octadienes 11 and 12 was isolated from this reaction. Deprotection of the TBDPS ethers gave a mixture of alcohols; only the undesired 14 underwent iodoetherification. Thus unreacted alcohol 13 could be recovered from the product mixture by simple column chromatography.

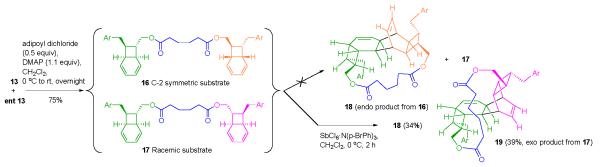

We were aware of the heroic efforts required to separate kingianin A from other kingianins during the isolation procedure. 15 Therefore, as a strategy for obtaining easily separable isomers from the dimerization step, we considered an intramolecular RCDA approach. We imagined linking two molecules of alcohol 13 by a removable tether and we hoped that we could find a pair of diastereomers in which the transition state geometry for endo cycloaddition could be reached only by the C-2 symmetric dimer. We thought that perhaps the racemic dimer would be recovered and easily separated from the expected pentacyclic product.

Several dimeric diesters were prepared from alcohol 13 and subjected to the RCDA conditions. Contrary to our expectation, in the case of each diastereomeric pair, both isomers appeared to have undergone the intramolecular cycloaddition reaction. Noteworthy in any case was the fact that the product mixture from the adipic acid-tethered substrate (16 and 17) consisted of two compounds, formed in approximately equal amounts and easily separated by chromatography. The more polar product displayed a 1H NMR spectrum that contained signals expected from a compound in the kingianin A series (see the Supporting Information for tabulated data). The identity of this product was firmly established as 18 by X-ray crystallography (see the Supporting Information).

The less polar product had a 1H NMR spectrum that differed in noticeable ways from those of compounds in the kingianin family. Furthermore, the absence of characteristic patterns in the spectrum was not the result of the presence of the tether; removal of the tether gave a diol, the NMR spectrum of which differed in important respects from that of kingianin D (Table 1 in the Supporting Information).

A series of coupling and NOE experiments allowed us to identify the second RCDA product as 19, the unanticipated but not surprising exo Diels Alder product. Complete data for this compound and data for the corresponding diol, along with the argument for the structure assignment, are presented in the Supporting Information.

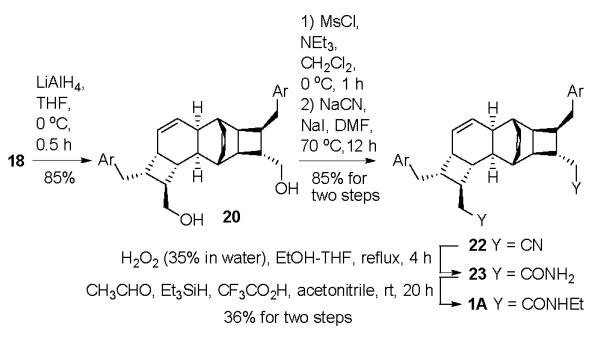

With some confidence that we had a significant intermediate in hand, we released the diol 20 from its tether in diester 18 and applied a double homologation procedure (Scheme 3). Mesylation and displacement by cyanide were followed by peroxide-promoted hydrolysis16 and the reductive N-alkylation procedure of Dube17 (as recently highlighted by Moses et al in the synthesis of prekingianin A).8 The 5-step sequence converted diol 18 to (±)-kingianin A (1A) in 26 % yield.

Scheme 3.

Removal of Tether and Double Homologation; Completion of the Total Synthesis of Kingianin A.

The total synthesis of (±)-kingianin A required 12 steps (longest linear sequence from commercially available materials and 14 steps total) and two silica gel chromatographic separations (of alcohol 13 and iodoether 15 and of tethered dimers 18 and 19). It demonstrates the use of the RCDA methodology in the synthesis of a complex natural product. Other homodimeric and also heterodimeric kingianins should be available by modification of the same overall strategy and we foresee the elaboration of the key diol 20 to other members of the kingianin family.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Preparation of the Tethered Substrates 16, 17, Postulated RCDA Product Mixture, and Actual RCDA Products

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (GM 74776) and to Stony Brook University for financial support of this work. In addition, we thank Te-Jung Hsu and Joseph Lauher (Stony Brook University) for the X-ray crystallographic structure determination and Francis Picart (Stony Brook University) for expert assistance with NMR studies.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- (1) (a).Leverrier A, Awang K, Gueritte F, Litaudon M. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leverrier A, Dau METH, Retailleau P, Awang K, Gueritte F, Litaudon M. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3638–3641. doi: 10.1021/ol101427m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).For representative examples, see Lim HN, Parker KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20149–20151. doi: 10.1021/ja209459f. erratum at J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4449. Sharma P, Powell KJ, Burnley J, Awaad AS, Moses JE. Synthesis. 2011:2865–2892. Beaudry CM, Malerich JP, Trauner D. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4757–4778. doi: 10.1021/cr0406110. and references therein.

- (3).Selected recent, informative reviews: Kilbride SM, Prehn JHM. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.348. Bodur C, Basaga H. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:1804–1820. doi: 10.2174/092986712800099839. Bajwa N, Liao C, Nikolovska-Coleska Z. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012;22:37–55. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.644274. Czabotar PE, Lessene G. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010;16:3132–3148. doi: 10.2174/138161210793292429.

- (4).Navitoclax, Abbott’s drug candidate ABT-263, currently in phase II clinical trials for lymphomas, leukemias, and small cell lung carcinoma, inhibits Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. See http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results/refine?term=navitoclax.

- (5).The endo/exo terminology for the bicyclooctadiene natural products is derived from the relationship of the aryl-substituted sidechain to the cyclohexadiene ring. See Parker KA, Lim Y–H. Org. Lett. 2004;6:161–164. doi: 10.1021/ol036048+.

- (6).Since its introduction for this purpose (see Beaudry CM, Trauner D. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2221–2224. doi: 10.1021/ol026069o. the Stille coupling / electrocyclization cascade method has been used consistently to access [4.2.0]-bicyclooctadienes.

- (7).Kim K, Lauher JW, Parker KA. Org. Lett. 2012;14:138–141. doi: 10.1021/ol202932x. See. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sharma P, Ritson DJ, Burnley J, Moses JE. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:10605–10607. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13949e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Ischay MA, Yoon TP. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012:3359–3372. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin S, Padilla CE, Ischay MA, Yoon TP. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:3073–3076. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lin S, Ischay MA, Fry CG, Yoon TP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:19350–19353. doi: 10.1021/ja2093579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gieseler A, Steckhan E, Wiest O, Knoch F. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- (10).An elegant demonstration of the properties of the RCDA was provided early on by Bauld in a total synthesis of the bicyclic sesquiterpene (−)-selinene; see Harirchian B, Bauld NL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:1826–8. See also reference 9c.

- (11).Bellville DJ, Bauld NL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;10:2665–2667. [Google Scholar]

- (12).For approaches to the asymmetric synthesis of [4.2.0] bicyclootadienes, see reference 7 and Parker KA, Wang Z. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3553–3556. doi: 10.1021/ol061328l.

- (13).Nicolaou KC, Petasis NA, Zipkin RE, Uenishi J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5555–5557. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Robles O, McDonald FE. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5498–5501. doi: 10.1021/ol902365n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).During the isolation procedure, kingianin A was separated from other kingianins by a series of flash chromatographies followed by a preparative HPLC experiment (reference 1).

- (16).For a study of effective media for this reaction, see Brinchi L, Chiavini L, Goracci L, Di Profio P, Germani R. Lett. Org. Chem. 2009;6:175–179.

- (17).Dube D, Scholte AA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2295–2298. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.