Abstract

Xeroderma pigmentosum Variant (XP-V) form is characterized by a late onset of skin symptoms. Our aim is the clinical and genetic investigations of XP-V Tunisian patients in order to develop a simple tool for early diagnosis. We investigated 16 suspected XP patients belonging to ten consanguineous families. Analysis of the POLH gene was performed by linkage analysis, long range PCR, and sequencing. Genetic analysis showed linkage to the POLH gene with a founder haplotype in all affected patients. Long range PCR of exon 9 to exon 11 showed a 3926 bp deletion compared to control individuals. Sequence analysis demonstrates that this deletion has occurred between two Alu-Sq2 repetitive sequences in the same orientation, respectively, in introns 9 and 10. We suggest that this mutation POLH NG_009252.1: g.36847_40771del3925 is caused by an equal crossover event that occurred between two homologous chromosomes at meiosis. These results allowed us to develop a simple test based on a simple PCR in order to screen suspected XP-V patients. In Tunisia, the prevalence of XP-V group seems to be underestimated and clinical diagnosis is usually later. Cascade screening of this founder mutation by PCR in regions with high frequency of XP provides a rapid and cost-effective tool for early diagnosis of XP-V in Tunisia and North Africa.

1. Introduction

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is an autosomal recessive cancer prone disease characterized by sensitivity to ultraviolet rays (UVR). XP patients are consequently predisposed to develop skin and eyes cancers [1]. This disease is caused by inherited mutations in DNA repair genes encoding proteins that protect cells from UV-induced damage. XP is genetically heterogeneous with seven XP complementation groups (XP-A to XP-G) defective in nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway and an additional “variant” form (XP-V) with normal NER but a deficient translesional synthesis.

XP-V patients have a relatively milder phenotype with a late onset of symptoms and delayed progression. Typically, XP-V patients do not have ocular or neurological abnormalities [2]. Many studies suggest that this form of XP is underdiagnosed [3, 4]. Therefore, XP-V patients represent only 20 to 30% of all XP cases [5].

Cells from XP-V patients are extremely hypermutable after exposure to UV due to the deficiency of pol eta [6, 7]. The DNA polymerase eta (η) normally catalyzes translesion synthesis (TLS) by incorporating dAMP opposite thymine residues of a cyclobutane thymine dimer (CPD) [8, 9]. In the absence of pol eta, the highly error-prone pol iota undertakes this bypass function resulting in the accumulation of UV-induced mutations and an increase in the susceptibility to skin cancer [10, 11].

Pol eta is encoded by the POLH gene, the human homolog of yeast Rad30 [9]. Pol η plays an important role in preventing genome instability after UV or cisplatin-induced DNA damage [12]. Chemoresistance of cancer to cisplatin treatment is due in part to human Pol η. Crystal structures of hPol η complexed with intrastrand cisplatin identified a hydrophobic pocket as a potential drug target for reducing chemoresistance [13].

More than 60 mutations have been identified in the POLH gene in cell lines derived from XP-V patients from different geographic locations, mainly Russia-Armenia, Scotland, Lebanon, Iran, Belgium, France, Japan, USA, Europe, Asia, Cayman Islands, Turkey, Israel, Germany, Korea, Algeria, and Tunisia [2–4, 9, 14–23].

In our study, we surveyed POLH mutations in 16 Tunisian patients with late onset of XP in order to assess the causative mutations of this disorder and to develop a rapid molecular diagnostic test.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

Sixteen suspected XP-V patients belonging to ten consanguineous Tunisian families originated from different regions of Tunisia were investigated (Table 2). Their age was ranging from 4 to 50 years.

Table 2.

Clinical features of Tunisian XP-V patients.

| Patients | Affected patients | Sex | Age (years) | Age at onset of the 1st XP macules erythema (years) | Geographic Origin |

Age at onset of 1st Tumor in years (Number of tumors) | Photophobia | Radiotherapy | Tumor post Radiotherapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC | SCC | Other tumors | |||||||||

| XPV6KE | 1 | M | 47 (died at 50) | 4 | Kef | 22 (6) | 20 (12) | — | +/− | +++ | +++ |

| XPV15GA | 1 | F | 18 | 4 | Gafsa | 15 (2) | 16 (2) | +/− | |||

| XPV17-1 B | 3 | F | 17 | 4 | Bizerte | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | ||

| XPV17-2 B | F | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | ||||

| XPV17-3 B | F | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | ||||

| XP18G | 1 | F | 43 | 4 | Gafsa | 16 (8) | 21 (3) | KA | +/− | +++ | +++ |

| XPV20G | 3 | F | 31 | 5 | Gafsa | ND (>10) | ND (>2) | +++ | + | ||

| XPV43-1 | 7 | M | ND | 5 | Zaghouan | 38 (8) | 23 (4) | KA and Actinic Keratosis | +/− | + (local) | — |

| XPV43-2 | F | 45? | 5 | 41 (1) | +/− | ||||||

| XPV48G | 1 | F | 46 | 6 | Gafsa | 0 | 47 (1) | +/− | |||

| XPV53Z | 1 | M | 50 | 7 | Fahs Zaghouan | 37 (4) | + (local) | +/− | |||

| XPV79-1 | 3 (1died) | F | 13 | 3 | Tozeur/Gafsa | 10 (3) | — | KA++ | +/− | ||

| XPV79-2 | F | 18 | 3 | KA | — | ||||||

| XPV91-1 | 3 | F | 29 | 6 | Tozeur | Actinic Keratosis | — | ||||

| XPV91-2 | F | 21 | 6 | — | |||||||

| XPV91-3 | F | 24 | 6 | — | |||||||

SCC: spino cell carcinoma; BCC: basal cell Carcinoma; KA: kerathoacantum; (+/−) moderate phenotype; (—) absence; (+++) several.

2.2. Methods

Written informed consent was obtained from all available family members or from parents of minor children. Families were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to collect information about family history, consanguinity, affected members, and associated diseases. DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocyte using salting-out method [24] or Qiagen kit DNA extraction.

2.2.1. Genetic Analysis

To confirm linkage to POLH gene, available family members were genotyped using two polymorphic microsatellite markers spanning a 0.4 Mb interval near to POLH locus (cen-D6S207 and D6S1582 (POLH-)tel) as previously described [4]. Microsatellite markers were selected from the genetic maps available on NCBI browsers and the CEPH genotype database (http://www.cephb.fr/en/cephdb/) on the basis of their heterozygosity percentage and closeness to the POLH gene. Genotyping was performed as described elsewhere [25].

2.2.2. PCR Long-Range

On absence of amplification of POLH exon 10, long PCR was performed using the Expand Long Template PCR System Kit (Expand Long Range dNTPack 700 units/μL Roche). PCR was performed using different primers (Table 3). The PCR program included 92°C for 2 min, 10 cycles of 92°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 15 sec, 68°C for 10 min, and 20 cycles of the same program except that the extension step was extended by 20 sec per cycle. PCR products were run on 1% agarose gel with the DNA ladder 1 kb molecular size marker (GeneRulerTM).

Table 3.

Complete list of primers used to gDNA amplification of exon 10 and its intronic boundaries.

| Name | Sequence 5′→3′ | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Suspected PCR products size (bp) | PCR Product size for XP-V patients (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPV10F | CCTGGTTCTTTTAATTTCCTCTCCTG | 55 | 459 | — |

| XPV10R | CATTTACCCTTTACCTCATTGAAGGAC | |||

|

| ||||

| XPV del 10 F | TCATTTGTGCTGTCCTGTTC | 60 | 3012 | — |

| XPV del 10 R | GGTTGCAGTGAGCGGAGATT | |||

|

| ||||

| Del ex10 LR-F | AGGTCCTCCCTAGTTACCCTATCACAGCAG | 60 | 4105 | — |

| Del ex10 LR-R | ACTACCTAACCCTGACTGACTTACCACTCTGG | |||

|

| ||||

| POLH10ΔF | AGTGGGTAGGTTTTGGTAGCTGTGGAAG | 60 | 9358 | ≈6000 bp |

| POLH10ΔR | GGACACACCCTGGATACTCTGTTGGTAA | |||

|

| ||||

| POLHFΔ | ACCTTGGAGTATAATTTCTGGGTCA | 59 | 5212 | ≈1000 bp |

| POLHRΔ | GTCATAAAGTTCCTCATTGTGTCTAA | |||

|

| ||||

| POLHdelF | CATGTGCTTGTTGGACATTTG | 60 | 4526 | ≈500 bp |

| POLHdelR | GGTTTCATGCTTTGGGACAG | |||

2.2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

As several genomic rearrangements are commonly caused by recombination events induced by repetitive elements present in the human genome, the genomic sequence of the POLH gene (NG_009252.1) was obtained and analyzed from chr6: 43578281 to 43581387 position corresponding to exon 9 to exon 11 region. Screening for repetitive elements was performed using the RepeatMasker software available at http://www.repeatmasker.org/ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequence analysis of repetitive elements of the 9358 bp sequence of POLH gene: 43572521–43581878 using repeat masker Software.

| score | % div. | % del. | % ins. | Query sequence | Position in query- | C + |

Matching repeat |

Repeat class/family | -Position in repeat (left) end begin | linkage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| begin | end | (left) | + | repeat | class/family | begin | end | (left) | id/graphic | |||||

| 1692 | 13.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 657 | 893 | (8465) | C | AluJr | SINE/Alu | (2) | 310 | 74 | 1 |

| 2266 | 10.4 | 0.3 | 4.3 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 925 | 1240 | (8118) | C | AluSq | SINE/Alu | (9) | 304 | 1 | 2 |

| 658 | 26.3 | 8.6 | 4.6 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 1267 | 1581 | (7777) | C | L1MA8 | LINE/L1 | (25) | 6266 | 5940 | 3 |

| 2432 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 1644 | 1944 | (7414) | C | AluSx1 | SINE/Alu | (10) | 302 | 2 | 4 |

| 3529 | 14.9 | 6.9 | 4.2 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 1958 | 2302 | (7056) | C | L1MB8 | LINE/L1 | (0) | 6178 | 5821 | 5 |

| 2464 | 10.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 2303 | 2609 | (6749) | C | AluSc5 | SINE/Alu | (2) | 307 | 1 | 6 |

| 3529 | 16.1 | 7.0 | 4.4 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 2610 | 3080 | (6278 | C | L1MB8 | LINE/L1 | (342) | 5820 | 5323 | 5 |

| 2287 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 3081 | 3372 | (5986) | + | AluSq2 | SINE/Alu | 1 | 308 | (5) | 7 |

| 1739 | 17.8 | 10.7 | 1.8 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 3373 | 3510 | (5848) | C | L1MB8 | LINE/L1 | (829) | 5333 | 5170 | 5 |

| 810 | 18.7 | 1.2 | 7.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 3744 | 3909 | (5449) | C | AluJo | SINE/Alu | (19) | 293 | 137 | 8 |

| 535 | 29.6 | 9.7 | 1.4 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 3990 | 4509 | (4849) | + | L2a | LINE/L2 | (2804) | 3365 | (61) | 9 |

| 2528 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 5271 | 5581 | (3777) | C | AluSx1 | SINE/Alu | (4) | 308 | 1 | 10 |

| 13 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 2.8 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 5582 | 5615 | (3743) | + | (TCTTTA)n | Simple_repeat | 1 | 36 | (0) | 11 |

| 684 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 6162 | 6233 | (3125) | + | AluSq10 | SINE/Alu | 1 | 72 | (241) | 12 |

| 2510 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 6991 | 7300 | (2058) | + | AluSq2 | SINE/Alu | 1 | 310 | (3) | 13 |

| 2679 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 7564 | 7863 | (1495) | C | AluSq | SINE/Alu | (13) | 300 | 1 | 14 |

| 2503 | 8.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 8018 | 8313 | (1045) | C | AluSg | SINE/Alu | (11) | 299 | 2 | 15 |

| 214 | 24.7 | 18.6 | 1.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 8598 | 8683 | (675) | + | MER5A | DNA/hAT-Charlie | 2 | 102 | (87) | 16 |

| 196 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | chr6:POLH:43572521+43581878 | 8684 | 8714 | (644) | + | MER5A | DNA/hAT-Charlie | (159) | 189 | (0) | 17 |

2.2.4. Sequencing and Mutation Analysis

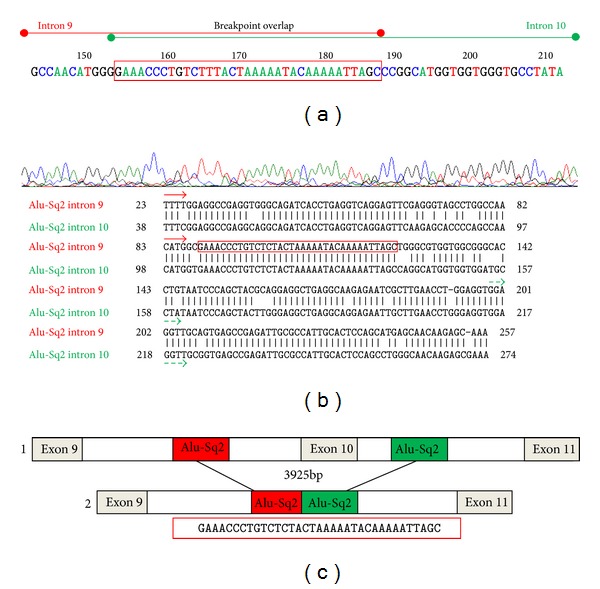

Long range PCR products were directly sequenced using the ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer by two pairs of primers (Table 3). Mutation analysis and breakpoints of the deletion were determined as the last nucleotide showing sequence identity between wild and mutated sequences (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the deletion breakpoints. (a) Electropherogram demonstrating the junction fragment resulting from the large deletion in the XP-V patients. Partial representation of introns 9 and 10 with the 35 bp breakpoint overlap framed in red. (b) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the genomic sequence of introns 9 and 10 of the POLH gene. Short vertical lines indicate matched bases between both introns. (c) Schematic representation of the deletion breakpoints and their flanking Alu Sq2 elements. (1) represents a normal gDNA fragment and (2) schematizes the mutated gDNA with a deletion of 3925 bp.

2.2.5. Mutation Nomenclature

The genomic reference of the POLH gene NG_011763.1 was used to annotate the deletion according to the HGVS version 2.0 (Mutalyzer 2.0.beta-26).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

In this study, we investigated sixteen patients with late onset of XP features. These patients belong to ten consanguineous families from different Tunisian geographic areas (Table 2). For all patients, skin hyperphotosensitivity to UVR began at a mean age of 4 years. The mean age at onset of the first skin cancer was 24 years. Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) occurred in only 10 patients. At least, 3 among them developed only basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and 5 developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) combined with BCC (Table 2).

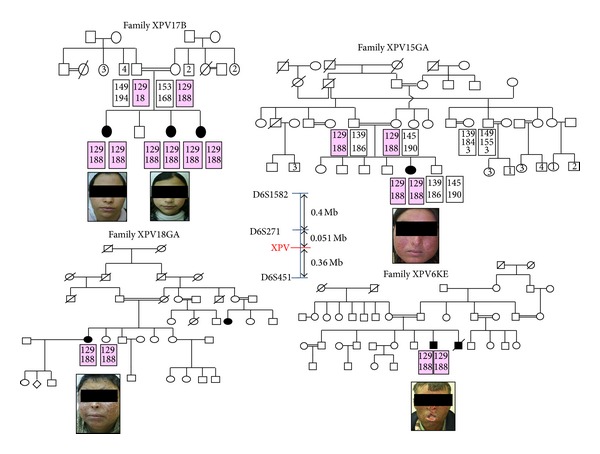

3.2. Genetic Analysis

The genetic examination of XP-V patients was initially assessed through routine procedures, which involved genotyping of all consanguineous XP-V patients and available related individuals. Haplotype analysis showed homozygosity for the closest two markers to POLH gene, D6S1582 and D6S271, with a founder haplotype (129–188) in all investigated patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pedigree and haplotype analysis for the XPV families (the disease haplotype is indicated by shading) and clinical photograph of each affected patient.

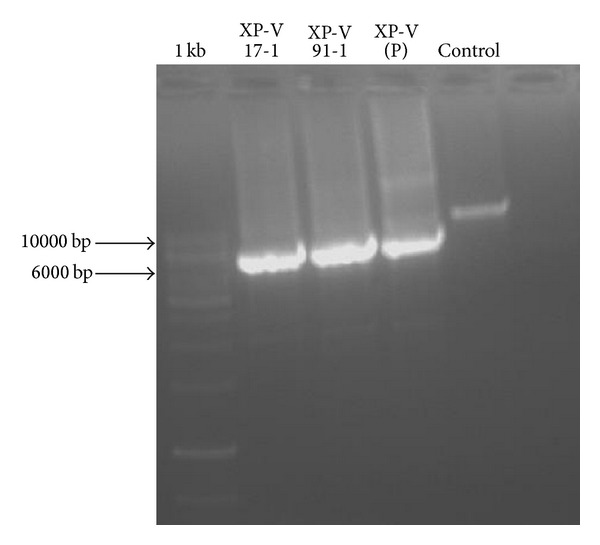

3.3. PCR Long-Range

DNA samples from these patients repeatedly failed to yield PCR amplification products for exon 10. Therefore, we assumed the presence of a genomic deletion spanning exon 10 (del exon 10). As del exon 10 was previously described in Italian patient at the genomic DNA level with 2.7 Kb deletion [2], we first screen for this deletion. Therefore, screening of this deletion by PCR did not yield any amplification product confirming that there are different breakpoints involved in our XP-V patients. In order to identify the deletion size, we amplified the sequence between exon 9 and exon 11 using primers POLH10ΔF and POLH10ΔR showed in Table 3. Long range PCR revealed a ≈ 6 kb product for XP-V patients versus ≈10 kb in control individual corresponding to approximately 4 kb size deletion (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Agar gel electrophoretic analysis of the PCR POLH gDNA of exon 10 and its intronic boundaries showed difference in the size between affected individuals (XPV17B-1 and XPV91) compared to healthy parents (XPV(P)) and a healthy control. (Marker: 1 kb DNA ladder molecular size marker (GeneRuler).)

3.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

Screening of repetitive elements present in exon 9 to exon 11 using repeat masker software revealed that 51.44% (4814 pb) of the sequence was interspersed repeat sequences. Among them, 11 SINE Alu sequences spanned a region of 2908 bp (31.08% of all the sequence) and 3 LINE sequences spanned a region of 1789 bp (19.12% of all the sequence). These Alu sequences are predicted to promote the occurrence of large deletions (Table 1).

3.5. Mutation Screening

In order to detect the breakpoints with accuracy, two internal primer pairs were designed to sequence introns 9 and 10 across the deletion (Table 3). Direct sequencing and analysis of the 6 kb PCR product (Figure 2) of XPV17 and XPV91 patients using primers POLHdelF and POLHdelR revealed that both the 5′ and 3′ breakpoints were located within homologous Alu Sq2 (class SINE (short interspersed elements, family Alu)) elements in introns 9 and 10 of POLH gene (Figure 3). This deletion POLH NG_009252.1: g.32438_36363del3926led to the loss of exon 10 (c.1370-2567_1539+1188del3925). This mutation has likely resulted from Alu-Alu equal homologous recombination.

3.6. Screening of Deletion by PCR

After identification of the deletion breakpoints in two patients (XPV91 and XPV17), we screened the following patients for this deletion by PCR using primers POLHdelF and POLHdelR showed in Table 3. In all patients, we found a product of 500 pb versus 4500 pb in virtual PCR. We then confirmed the presence of the same breakpoints by direct sequencing.

For individuals at a heterozygous state, we confirmed their profiles by two PCRs. The presence of one allele of exon 10 was confirmed using XPV10F and XPV10R primers and the absence of exon 10 on the other allele was confirmed using POLHdelF and POLHdelR primers.

4. Discussion

We report 16 cases with NMSC, BCC, and SCC that occurred with a mean delay of 24 years after XP diagnosis. Five of our patients (XPV6KE, XP18G XPV20G, XPV43-1, and XPV53Z) had been treated by skin radiotherapy (Table 2). After cancer treatment, many NMSC appeared. For example, XPV6KE died after frontal tumor metastasis and XPV18G experienced a metastasis after recurrence on the right cheek. These consequences may be explained by the significant role of pol eta in cancer radiotherapy response. Pol eta-deficient cells are resistant to ionizing radiation. This radioresistance results from the increased reparation of double strand breaks by homologous recombination repair system (HR) [26]. While for chemotherapy, previous studies demonstrate that pol eta-deficient cells are very sensitive to cisplatin and oxaliplatin and particularly for agents which exert their activities by blocking DNA replication forks [27]. Among the roles of pol eta is repairing lesions induced by cisplatin. Consequently, systemic chemotherapy using cisplatin will attack healthy cells and induce novel cancers on absence of pol eta. This type of chemotherapy may be very dangerous for XP-V patients. Knowing this important role of pol eta, mutation screening of POLH gene in patients with SCC or BCC could have an impact in guiding treatment choice.

Previous studies showed two specific mutations (c.1568_1571delGTCA and c.660+1G>A) in three XP-V Tunisian patients [4, 20]. Deletion of exon 10 has been previously described at the cDNA level in XP-V patients from different geographic origins. It was found at homozygous state in two Algerian (XP62VI and XP75VI) and in one American (XP139DC) and at heterozygous state in one Tunisian (XP28VI) XP-V patients [3, 16]. Also, POLH del exon 10 has been described at genomic level in one Italian patient with 2.7 Kb deletion occurring between two poly (T) sequences [2] and in one Algerian XP-V patient with 3.763 bp deletion [22]. We report here a novel breakpoint of del exon 10, POLH NG_009252.1: g.32438_36363del3926, that presents in 16 XP-V Tunisian patients belonging to 10 unrelated families. This deletion can be screened by a simple PCR without confirming by sequencing. This rapid tool may facilitate molecular investigation of XP-V patient.

This mutation is probably a founder variation because it was carried by a particular haplotype (129–188 or 129–186). Del exon 10 is common in the world and probably it may be due to different founder effects. Repetitive sequences are the primary candidates to generate stable abnormal secondary structures producing large deletion during replication [28]. Alu elements are normally located within introns and 3′ untranslated regions of genes, which are considered mutational “hotspots” for large gene rearrangements [29]. Large deletions in POLH gene have been previously described in exons 5 and 6 [3, 16]. Similar founder mutations in the POLH gene have been reported in other populations such as Japanese and Korean. Therefore, 87% of the Japanese XP-V patients shared one of the four founder mutations described in Japan [3, 18].

5. Conclusion

The presence of this founder mutation, reported in our study, could simplify genetic screening of XP patients in Tunisian population by implementing presymptomatic tests and hence early UV protection. Before treatment of patients' skin cancers, XP status should be verified to avoid cancer recurrence. It is also important to consider the possible existence of such large deletion at heterozygous state. Consequently, we propose systematic screening of this mutation in all XP-V patients by two PC reactions; the 1st will amplify exon 10, while the 2nd will amplify across deletion breakpoints. After confirmation at a large scale in XP Tunisian patients, the test will be proposed for patients from Southern Mediterranean and Middle East countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families as well as the patients' support group “Helping Xeroderma Pigmentosum Children” (http://www.xp-tunisie.org.tn/) for their collaboration. This work was supported by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (Laboratory on Biomedical Genomics and Oncogenetics, no. LR 11 IPT 05) and the Tunisian Ministry of Public Health.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Kraemer KH, Patronas NJ, Schiffmann R, Brooks BP, Tamura D, DiGiovanna JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: a complex genotype-phenotype relationship. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1388–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratchev A, Strein P, Utikal J, Sergij G. Molecular genetics of Xeroderma pigmentosum variant. Experimental Dermatology. 2003;12(5):529–536. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2003.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inui H, Oh KS, Nadem C, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients from America, Europe, and Asia. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2008;128(8):2055–2068. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rekaya MB, Messaoud O, Mebazaa A, et al. A novel POLH gene mutation in a Xeroderma pigmentosum-V Tunisian patient: phenotype-genotype correlation. Journal of Genetics. 2011;90(3):483–487. doi: 10.1007/s12041-011-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriwaki S, Kraemer KH. Xeroderma pigmentosum—bridging a gap between clinic and laboratory. Photodermatology Photoimmunology and Photomedicine. 2001;17(2):47–54. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.017002047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannouche P, Stary A. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant and error-prone DNA polymerases. Biochimie. 2003;85(11):1123–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stary A, Kannouche P, Lehmann AR, Sarasin A. Role of DNA polymerase η in the UV mutation spectrum in human cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(21):18767–18775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masutani C, Araki M, Yamada A, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XP-V) correcting protein from HeLa cells has a thymine dimer bypass DNA polymerase activity. EMBO Journal. 1999;18(12):3491–3501. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A, et al. The XPV (Xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η . Nature. 1999;399(6737):700–704. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumstorf CA, Clark AB, Lin Q, et al. Participation of mouse DNA polymerase ι in strand-biased mutagenic bypass of UV photoproducts and suppression of skin cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(48):18083–18088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605247103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gueranger Q, Stary A, Aoufouchi S, et al. Role of DNA polymerases η, ι and ζ in UV resistance and UV-induced mutagenesis in a human cell line. DNA Repair. 2008;7(9):1551–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruet-Hennequart S, Gallagher K, Sokòl AM, Villalan S, Prendergast AM, Carty MP. DNA polymerase η, a key protein in translesion synthesis in human cells. Sub-Cellular Biochemistry. 2010;50:189–209. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3471-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Biertumpfel C, Gregory MT, Hua YJ, Hanaoka F, Yang W. Structural basis of human DNA polymerase η-mediated chemoresistance to cisplatin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(19):7269–7274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202681109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh T, Linn S. XP43TO, previously classified as Xeroderma pigmentosum group E, should be reclassified as Xeroderma pigmentosum variant. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2001;117(6):1672–1674. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson RE, Kondratick CM, Prakash S, Prakash L. hRAD30 mutations in the variant form of Xeroderma pigmentosum. Science. 1999;285(5425):263–265. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broughton BC, Cordonnier A, Kleijer WJ, et al. Molecular analysis of mutations in DNA polymerase η in Xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(2):815–820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022473899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanioka M, Masaki T, Ono R, et al. Molecular analysis of DNA polymerase eta gene in Japanese patients diagnosed as Xeroderma pigmentosum variant type. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2007;127(7):1745–1751. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masaki T, Ono R, Tanioka M, et al. Four types of possible founder mutations are responsible for 87% of Japanese patients with Xeroderma pigmentosum variant type. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2008;52(2):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Zhang X, Qiao J, Fang H. Identification of a novel nonsense mutation in POLH in a Chinese pedigree with Xeroderma pigmentosum, variant type. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;10(6):766–770. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messaoud O. Novel mutation in POLH gene responsible of severe phenotype of XP-V. Clinical Dermatology. 2013;1:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono R, Masaki T, Takeuchi S, et al. Three school-age cases of Xeroderma pigmentosum variant type. Photodermatology Photoimmunology and Photomedicine. 2013;29(3):132–139. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opletalova K, Bourillon A, Yang W, et al. Correlation of phenotype/genotype in a cohort of 23 Xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients reveals 12 new disease-causing POLH mutations. Human Mutation. 2014;35(1):117–128. doi: 10.1002/humu.22462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortega-Recalde O, Vergara JI, Fonseca DJ, et al. Whole-exome sequencing enables rapid determination of Xeroderma pigmentosum molecular etiology. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064692.e64692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 1988;16(3, article 1215) doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouchlaka C, Abdelhak S, Amouri A, et al. Fanconi anemia in Tunisia: high prevalence of group A and identification of new FANCA mutations. Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;48:352–361. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolay NH, Carter R, Hatch SB, et al. Homologous recombination mediates S-phase-dependent radioresistance in cells deficient in DNA polymerase eta. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(11):2026–2034. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YW, Cleaver JE, Hanaoka F, Chang CF, Chou KM. A novel role of DNA polymerase η in modulating cellular sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents. Molecular Cancer Research. 2006;4(4):257–265. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebow D, Miselis N, Liber HL. Homologous and nonhomologous recombination resulting in deletion: effects of p53 status, microhomology, and repetitive DNA length and orientation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(11):4028–4035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4028-4035.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 1999;67(3):183–193. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]