Abstract

The etiology of central nervous system (CNS) tumor heterogeneity is unclear. To clarify this issue, a novel animal model was developed of glioma and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid-like tumor (ATRT) produced in rats by non-viral cellular transgenesis initiated in utero. This model system affords the opportunity for directed oncogene expression, clonal labeling, and addition of tumor-modifying transgenes. By directing HRasV12 and AKT transgene expression in different cell populations with promoters that are active ubiquitously (CAG promoter), astrocyte-selective (GFAP promoter), or oligodendrocyte-selective (MBP promoter); thus, generating glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (AO), respectively. Importantly, the GBM and AO tumors were distinguishable at both the cellular and molecular level. Furthermore, proneural basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, Ngn2 (NEUROG2) or NeuroD1, were expressed along with HRasV12 and AKT in neocortical radial glia, leading to the formation of highly lethal atypical teratoid/rhabdoid-like tumors (ATRT). This study establishes a unique model in which determinants of CNS tumor diversity can be parsed out and reveals that both mutation and expression of neurogenic bHLH transcription factors contributes to CNS tumor diversity.

Keywords: CNS tumor, glioma, Neurogenin2, Neuronal Differentiation 1, piggyBac

Introduction

Tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) have significant intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity in terms of cellular composition, cellular proliferation, invasiveness and epigenetic status (1, 2). Integrative large scale gene expression analysis of 200 GBM tumors revealed 4 subtypes: proneural, neural, classical and mesenchymal (1). A more recent GBM classification based on a combination of epigenetics, copy number variation, gene expression and genetic mutations has lead to identification of as many as six GBM subgroups (2). In addition, there are at least two prognostic subgroups of pediatric GBM based on association with or without aberrantly active Ras/AKT pathway (3, 4). Heterogeneity in GBM tumors may be responsible for differential response to therapeutic interventions (1), and understanding the etiology of tumor heterogeneity in animal models may become increasingly important to design therapeutic strategies effective at targeting molecularly defined tumor subtypes.

Several animal models of brain tumor, including xenograft models, genetically engineered mouse models (GEMs) and models utilizing virus-mediated somatic cell transgenesis have been used to address important aspects of CNS tumor biology. For example, GEMs harboring mutations found in human gliomas have been used to assess tumorigenic effects of individual genes and mutations and to reveal the tumor cell-of-origin in some models (5, 6). Endogenous cell populations have been induced to form gliomas by both viral and non-viral somatic transgenesis of oncogenes or deletion of tumor suppressor genes in specific target cell populations (7–17). For example, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) can be the cell-of-origin for adult glioma (5, 6, 13) with OPC originated glioma matching the human proneural subgroup of GBM (6, 18). Friedmann-Morvinski et al. found that RNAi knock-down of NF1 and p53 expression in either astrocytes (GFAP+) or neurons (SynI+) induced formation of mesenchymal GBM subtypes, while the same RNAi in Nestin positive neural progenitors induced neural GBM subtypes (16). To more fully explore causes of tumor diversity in cerebral cortex we have developed an animal model in which multiple transgenes can be expressed in selected cell populations at different times in forebrain development.

DNA transposon systems have been previously adapted to non-viral somatic transgenesis in studies of neocortical development (19, 20), cellular reprogramming (21), and to generate animal models of glioma (17). In utero electroporation is a relatively efficient method to deliver multiple combinations of transgenes into neuronal and glial progenitors in the developing forebrain in utero (22). When combined with a DNA transposon system including cell-type specific promoters, it becomes possible to introduce multiple transgenes, including oncogenes, in different populations of cells (19, 20, 23, 24). Active Ras pathway (25) and PI3K-AKT pathway (9, 26) have been frequently found in human glioma patients and used in various glioma animal models (9, 10, 12, 15). In the model described here, we introduced HRasV12 and AKT in cell populations in the radial glia lineage to ask whether diversity in glioma is linked to the population of cells induced to express oncogenic transgenes. We also tested whether addition of neurogenic transcription factors to the starting progenitor population modifies tumor type. We show by several measures including morbidity, histology, developmental time course, tumor clonal pattern and molecular signature, that diverse tumors are generated when oncogene expression is directed into different cell populations. Moreover, expression of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors Ngn2 or NeuroD1 along with HRasV12 and AKT results in atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor like tumors (ATRT-like), a pediatric tumor type rarely produced in existing tumor models.

Methods

Plasmids

A system of piggyBac transposon donor and helper plasmids were produced and used in this study. To make the donor plasmid PBCAG-HRasV12 and PBCAG-AKT, HRasV12 was PCR amplified from pTomo (15) (Addgene plasmid 26292), human AKT was amplified from 1036 pcDNA3 Myr HA Akt1, (26) (Addgene plasmid 9008) respectively and inserted into the EcoRI/NotI sites of pPBCAG-eGFP (19). For construction of PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT, PBMBP- HRasV12/AKT, HRas-V12 and AKT were inserted into EcoRI/NotI sites of PBGFAP-GFP and PBMBP-GFP respectively (19). For the bHLH donor plasmids PBCAG-Ngn2 and PBCAG-NeuroD1, human Neurogenin2 cDNA clone (IMAGE ID 5247719), human Neuronal differentiation1 cDNA (IMAGE ID 3873419) were purchased from Open Biosystem, PCR amplified and inserted into PBCAG-eGFP EcoRI/NotI sites. CAG-Ngn2 was made by inserting Ngn2 coding sequence into EcoRI/NotI sites of pCAG-eGFP.

Animals

Pregnant Wistar rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA) and maintained at the University of Connecticut vivarium on a 12 h light cycle and fed ad libitum. Animal gestational ages were determined and confirmed during surgery. Both male and female subjects were used for tumor induction. For the purpose of constructing survival curves (Figures 2A, 3A) rats were removed from the experiment for humane purposes when they became unable to eat or drink. At the end of the 40 week survival experiment, percentage of survival for each preceding week was calculated and % survival curves were generated. For tumors induced by PBCAG-Ngn2/PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT and PBCAG-NeuroD1/PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT, survival rates were also calculated for each day. To statistically compare survival rates a log rank test, Breslow test and Tarone-Ware test were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics 21). All procedures and experimental approaches were approved by the University of Connecticut IACUC.

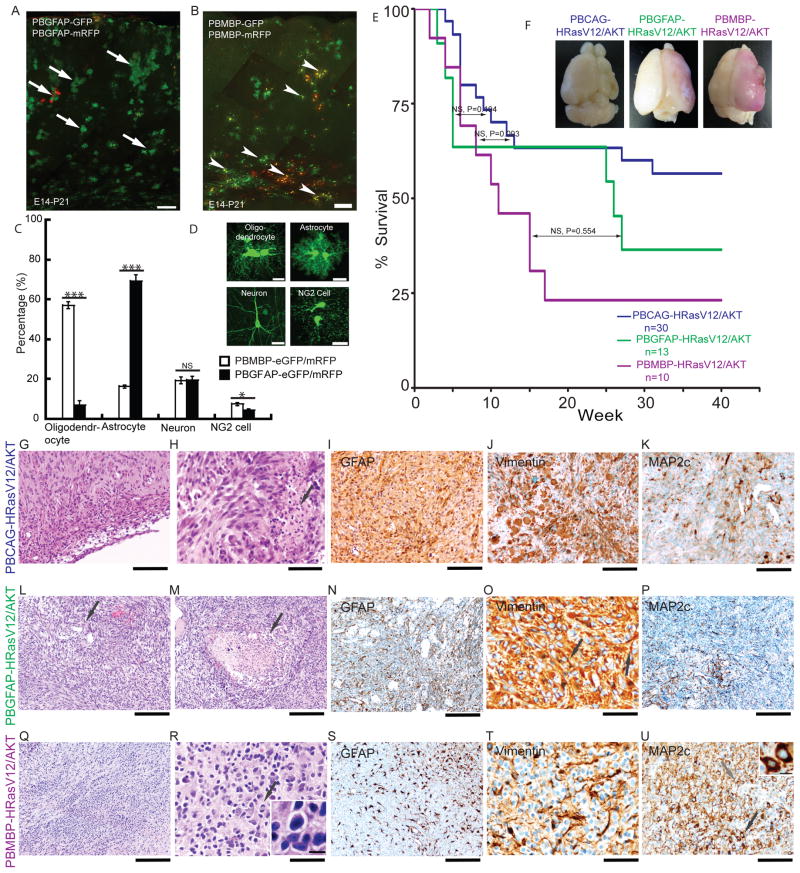

Figure 2. Distinct tumor types are induced by different donor plasmids.

(A)Mouse GFAP promoter fragment labeled astrocytes. (B) Rat MBP promoter fragment labeled oligodendrocytes.

(C) Quantification of proportions of labeled cells by GFAP and MBP promoter fragments (One way ANOVA * indicates P<0.05 and *** indicates P<0.01. NS indicates no significance difference). (D) Representative images of neuron, astrocyte, oligodendrocyte and NG2 cell. (E–F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves and representative appearance of tumor bearing brains. Log rank test showed no difference in survival across all groups. (G–K) Characterization of tumors induced by PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT. (G) Subarachnoidal spread of tumor cells (H&E). (H) Necrosis (black arrow, H&E). (I–K) Tumor cells with fibrillary processes were positive for GFAP, vimentin and MAP2. (L–P) Characterization of tumors induced by PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT. (L) Overview of H&E staining. Black arrow indicates vessels. (M) Necrosis (black arrow). (N–P) GFAP, Vimentin and MAP2 positive processes. (Q–U) Characterization of tumors induced by PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT. (Q) Prominent oligodendroglial components (H&E). (R) Round cell appearance of tumor cell (inset) and mitosis (black arrow, H&E). (S) GFAP positive astroglial process. (T) Oligodendroglial cells were vimentin negative while astroglial elements were vimentin positive. (U) MAP2 positive oligodendroglial component (black arrow, inset) and MAP2 positive astrocytes component (gray arrow).

Scale bar: 200μm in A,B, L–N, P, Q, S; 100μm in G, I–K and; 50μm in H, O, R, T; 20μm in D and 10μm in inset in R and U.

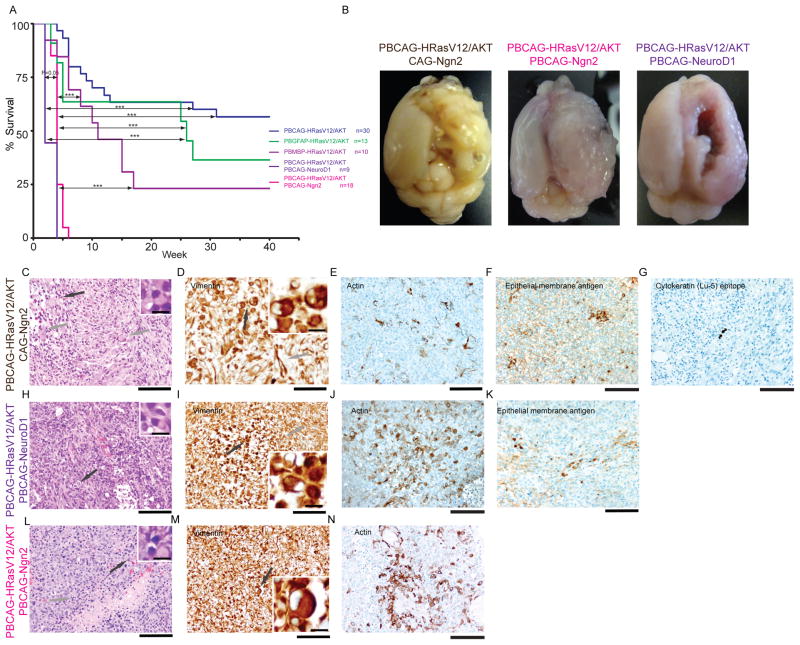

Figure 3. ATRT like tumor was induced by addition of Ngn2 or NeuroD1 to PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT.

(A, B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves and representative images of ATRT like tumor bearing brains. ATRT like tumor bearing animals had significantly short survival compared to GBM and anaplastic oligoastrocytoma bearing animals (log-rank test,* indicates P< 0.05, *** indicates P<0.01). (C–G) ATRT like tumor is induced by addition of CAG-Ngn2 to PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT mixture. (C) Rhabdoid components (black arrow, inset), neuronal differentiation (grey arrows, H&E). (D) Vimentin rhabdoid cellular elements (black arrow, inset), and processes/glial differentiation (grey arrows). (E) Individual cells were actin positive. (F) Clusters of cells express epithelial membrane antigen. (G) Few cells were positive for cytokeratin (Lu-5 epitope). (H–K) ATRT like tumor is induced by addition of PBCAG-NeuroD1 to PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT mixture. (H) Necrotizing tumor with mitoses, rhabdoid cellular differentiation (black arrow, inset), process rich and epitheloid portions (H&E). (I)Vimentin positive rhabdoid components (black arrow, inset) as well as Vimentin positive processes (grey arrow). (J) Actin positive cells. (K) Epithelial membrane antigen – clusters of positive cells. (L–N) ATRT like tumor is induced by addition of PBCAG-Ngn2 to PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT mixture. (L) H&E – tumor with high cellularity and undifferentiated appearance (mitotic figure – grey arrow; rhabdoid cell - black arrow, inset). (M) Vimentin staining, individual rhabdoid components (black arrow, inset) in an environment of a glial process rich meshwork. (N) Clusters of actin positive cells.

Scale bar: 100μm in C and E–N and 50μm in D and 10μm in all insets.

In utero electroporation

In utero electroporation was performed as previously described (19, 20, 27). Electroporation was performed at embryonic day 14 or 15 (E14 or E15) and gestation age was confirmed during surgery. All plasmids were used at the final concentration of 1.0 μg/μl except PBCAG-CFP and GLAST-PBase were used at the final concentration of 2.0 μg/μl.

Image acquisition and 3D reconstruction

Multi color imaging was performed as described using Zeiss Axio imager M2 microscope with Apotome with 488/546/350 nm filter cubes and the X-Cite series 120Q light source (20). All the images were further processed in Adobe Photoshop CS3 software (San Jose, CA). For 3D reconstruction, P27 Wistar rats were deeply anesthetized with Isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (4% PFA). Samples were post fixed overnight in 4% PFA and sectioned at 65 μm thickness on vibratome (Leica VT 1000S). Sections were mounted onto microscope slides in sequential order, all aligned in the same dorsal-ventral and left-right arrangement. Images were acquired with Stereo Investigator (Microbright Field, VT). After imaging acquisition, outlines of the cerebral hemisphere and tumor clones were traced using color-coded contours for the hemisphere and each clone. Then traced images were transferred to Neurolucida Explorer (Microbright Field, VT), in which several contours from sequential sections were appended to one another, and organized and stacked in order. 3D model was created using Neurolucida Explorer software 3D visualization option to visualize the clonality of selected clones of tumor cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were deeply anesthetized with Isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (4% PFA). Samples were post fixed overnight in 4% PFA. For immunofluorescence, brains were sectioned at 65 μm thickness on a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S). Sections were processed as free-floating sections and stained with GFAP (Cell Signaling, 3670X), CC1 (Calbiochem, OP80) and NG2 (Chemicon, AB5320) antibody. Images were acquired and processed as previous described (19, 20).

For histological analysis, immnunohistochemsitry and H&E staining were carried out on paraffin embedded 4μm sections as described in (28, 29) using GFAP (DAKO, Z0334), MAP2c (Sigma, M4403), Vimentin (DAKO, M0725), Synaptophysin (DAKO, M0776), Cytokeratin (BMA Medicals, T-1302), Actin (DAKO, M0851), epithelial membrane antigen (DAKO, M0613) antibody.

Tumor cell culture

Tumors were dissected from PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT transfected animals at the age P21. After dissection, tumor tissues were chopped and trypsinized into single cell suspension. Then cells were cultured in a serum-free medium consisting of DMEM with L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, B-27, N-2, bFGF and EGF (Invitrogen, CA). 2 days later, tumor cell adherent cultures were passaged into neurosphere suspension cultures at a density of 10cells/μl and allowed to grow for 3 days to form tumor spheres.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR

Animals aged P21 to P27 were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane. Brains were quickly removed on ice. Tumors were identified on the brain surface, removed and then chopped into cubes. Tissue from the opposite hemisphere that was tumor free was used as control. RNA extraction was performed using Ambion® RNAqueous® Kit (Invitrogen, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche) following manufacture’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using Fast SYBR® Green master mix (Applied Biosystem, CA). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Triplicates were included from each sample. Fold of regulation of gene expression was calculated using ΔΔCt method. More specifically, the Ct values obtained from tumor and control brain RNA samples are directly normalized to a housekeeping gene (GAPDH). ΔΔCt is the difference in the ΔCt values between the tumor and control samples. The fold-change in expression of the gene of interest between the tumor and control brain is then equal to 2^ (−ΔΔCt). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed on fold of regulation for each of the 24 genes profiled and a heat map was generated using the clustergram command in the MATLAB bioinformatics toolbox (Math Works, MA). Other statistical analyses were performed using KaleidaGraph version 4.0 (SynergySoftware 2006). A confidence interval of 95% (p < 0.05) was required for values to be considered statistically significant. All data are presented as means and standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

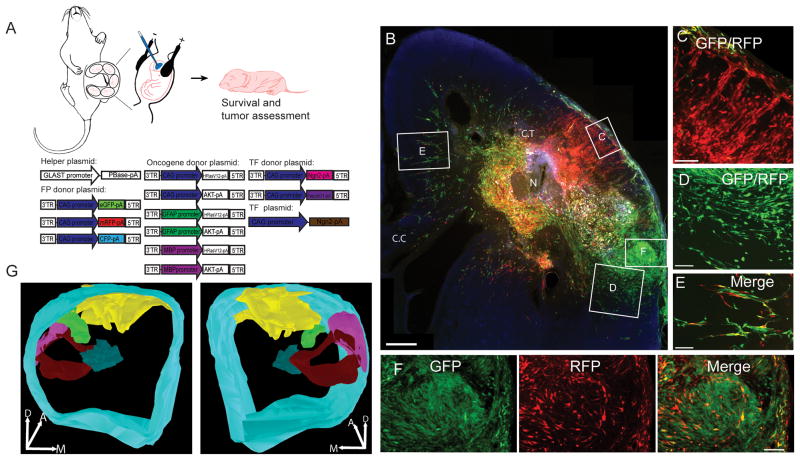

A model of GBM by piggyBac-mediated somatic transgenesis

We developed a non-viral somatic cell transgenesis approach to produce tumors from endogenous rat neural progenitors in vivo. HRasV12 and AKT transgenes were introduced into embryonic neocortical neural progenitors, also known as radial glial progenitors, by in utero electroporation of the lateral ventricles of embryonic rats. For non-viral cellular transgenesis we produced a system of plasmids consisting of a helper plasmid that expresses the piggyBac transposase in radial glial progenitors via the GLAST promoter (GLAST-PBase) and thereby drives transposon integration into the genomes of radial glia progenitors, and a set of donor plasmids containing transgenes flanked by transposon inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) to be integrated into the genome by piggyBac transposase activity. The donor plasmids included HRasV12 and AKT under the control of one of three different promoters (CAG, MBP or GFAP), (Figure 1A) and a multicolor system of donor plasmids (20) with the CAG promoter driving expression of eGFP, mRFP or CFP to create multicolor clonal labeling (Fig 1A) (20, 30). Electroporation of this system of plasmids unilaterally into the lateral cerebral ventricles of E14–E15 rat embryos (Fig 1A) invariably resulted by twenty one days after birth in the formation of large unilateral tumors (Figure 2F). Tumors were composed of both regions of uniformly colored cells indicating significant regionalized clonal expansion (Fig. 1C and D), and regions containing a mixture of differently colored cells indicating clonal mixing (Fig. 1F). In addition to tumors, streams of cells typically of one or 2 different colors were found distal to the tumor core. These streams were frequently in directionally oriented chains suggesting migration and invasion into surrounding neural tissue (Fig. 1E). Survival experiments showed that tumor bearing animals began dying at 3 weeks of age and the rate of death appeared stable by 31 weeks after birth for the CAG donor plasmid treated animals (Fig. 2E). Tumors were confirmed in all electroporated animals (30/30).

Figure 1. Multicolor rat glioma.

(A) Schematic representation of piggyBac IUE approach and plasmids used. In utero electroporation was performed between E14–E15 with plasmids listed. We used the multicolor piggyBac system to clonally label cells, oncogene donor plasmids to induce tumors and both donor and conventional epsiomal plasmids encoding transcription factors to evaluate their role in gliomagenesis. After the animals were born, tumor assessment was performed at different postnatal ages. (B) Representative images of a P22 rat brain hemisphere transfected with multicolor piggyBac plasmids and PBCAG-HRasV12/ATK donor plasmids. Necrosis is labeled with N. (C) Overlay image showing large regions of tumor cells were uniformly labeled with mRFP. (D) Overlay image showing other regions of tumor were uniformly labeled with eGFP. (E) Streams of tumor cells invading tissue adjacent to tumors. (F) Region of the tumor containing a mixture of red and green labeled tansformed cells indicating regions of clonal mixing. (G) 3D reconstruction of 5 tumor clones in a P27 rat transfected with PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT. CT, cortex. CC, corpus callosum. Scale bar: 500 μm in B and 100 μm in C, D, E and F.

Histologically, tumors induced by HRasV12 and AKT driven by the CAG donor plasmids were composed of fibrillary and gemistocytic elements (Supplementary Figure 1A). The tumors diffusely infiltrated neighboring tissues (Supplementary Figure 1B) and had cells with highly pleomorphic cytological appearance, and increased mitotic activity indicative of malignancy (Supplementary Figures 1C). Tumor cells frequently invaded the subarachnoidal space (Fig. 2G), and tumors had areas of necrosis indicative of high malignancy (Fig 2H arrow). Tumors appeared by P7 and necrotic areas were found as early as at P4. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that tumor cells showed strong positivity for GFAP (Figure 2I), Vimentin (Figure 2J) and MAP2 (Figure 2K). Some neurons entrapped within tumors were positive for synaptophysin, while the bulk of the tumors did not show synaptophysin positivity. Interestingly, we did not observe vascular proliferation in the rat tumors produced by the CAG donor plasmids but observed vascular proliferation in tumors induced by all other plasmid combinations used in this study. Moreover when cultured in neurosphere suspension medium, tumor cells can form tumor spheres (Supplementary Figure 2). In sum, the piggyBac transposon system effectively produces a tumor model resembling human GBM (WHO Grade IV).

MBP and GFAP promoter directed oncogene expression produces distinct tumor types

The binary piggyBac system allows for directing insertion of transgenes in one population of cells (i.e. radial glia neural progenitors), but then delayed expression of oncogene expression in later generated cell types in the lineage. This feature allowed us to introduce oncogenes into neural progenitors at the embryonic lateral ventricle surfaces, but then have their expression turned on later, primarily in either astrocytes, or oligodendrocytes. For this experiment, we constructed donor plasmids in which HRasV12 and AKT expression was controlled by either a mouse GFAP promoter fragment (19) (PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT) or a rat MBP promoter fragment (31) (PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT). We first assessed the activity of the mouse GFAP and rat MBP promoters using GFP as a reporter. We found that the GFAP promoter resulted in 69.3±3% astrocytes, 19.4±2% neurons, 7.1±2% oligodendrocytes and 4.3±0.7% oligodendrocyte precursor cells. In contrast, the MPB promoter construct (PBMBP-eGFP/mRFP) labeled 57.0±2% oligodendrocytes, 16.2±0.7% astrocytes, 19.3±2% neurons, and 7.5±0.7% oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Figure 2C and D). One way ANOVA showed a significant difference between GFAP and MBP promoter labeled astrocytes (p= 6.91E-05) and oliogodendrocytes (p=2.69E-05). A significant difference was also found between NG2 cells labeled by GFAP and MBP promoters (One-way ANOVA, p=0.021172), but no significant difference was found between the fraction of labeled neurons (One-way ANOVA, p=0.989884). The differences in the cell populations labeled by the MBP and GFAP promoter fragments is consistent with enriched targeting of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes respectively; however, each promoter was also capable of labeling some fraction of each cell type.

We next compared and contrasted tumors produced by the donor plasmids containing either the GFAP or MBP promoters driving oncogene expression. For both donor plasmids, tumors resulted in all animals and death resulted in 65.2% (15/23) of animals by 40 weeks (Figure 2E and F). A log rank test showed no significant difference in survival among animals bearing tumors induced by GFAP, MBP or CAG donor plasmids (Log rank test, p=0.194 between CAG and GFAPP, p=0.554 between GFAP and MBP donor plasmids transfected animals. For comparison between CAG and MBP donor plasmids transfected animals, Log rank test p=0.093, Breslow test p=0.121, Tarone-Ware test p=0.106). A histopathological analysis of tumors in both GFAP and MBP promoter conditions indicated frequent mitotic figures (Supplementary Figure 1D, Fig. 2R, black arrow), similar to the CAG promoter condition described above, but also showed vascular proliferates consistent with highly malignant tumor types. Tumors were observed in 23 out of 23 animals assessed for tumors 14 days to 280 days after birth. In addition, GFAP donor plasmid induced tumors, unlike the MBP plasmids, resulted in tumors with prominent necrotic foci frequently surrounded by “pseudopalisading” tumor cells (Fig 2M arrow). Immunohistological assessment of tumors induced by GFAP donor plasmids indicated process rich astroglial cells with delicate processes positive for GFAP, Vimentin and MAP2 (Figure 2N–P). We conclude based on the histopathological findings that the GFAP donor plasmid induced tumors are malignant astroglial tumors resembling human GBM (WHO Grade IV). While similar in many ways to tumors induced by the CAG donor plasmid the multicolor clonal analysis indicated that the GFAP donor plasmids resulted in tumors with larger clonal territories than the CAG donor plasmids. Similarly, the tumors in the GFAP donor plasmid condition showed more clonally associated invasion and expansion into striatum than did tumors in the CAG donor plasmid condition.

In contrast to the GFAP and CAG donor plasmid induced tumors, the MBP donor plasmids induced tumors contained a mixture of astroglial and oligogdendroglial components, and lacked prominent necrotic foci and pseudopalisading cell arrangements typical of the GFAP donor plasmids induced tumors (Figure 2M). In some areas of MBP donor plasmid induced tumors there were processes with GFAP and Vimentin positivity (Figure. 2S and T), but these areas were less frequently observed than in the GFAP donor plasmid induced tumors. In addition to the small astroglial cell fraction, the MBP donor plasmid induced tumors contained prominent ‘honeycomb’-like cell clusters (Figure 2Q) with round isomorphic nuclei located centrally to perinuclear halos (Figure 2R inset): a feature resembling cytological characteristics of human oligodendroglioma. Cells were largely negative for Vimentin (Fig. 2T), but positive for MAP2, an immunostaining pattern consistent with mixed oligodendroglial and astroglial components. MAP2 immunopositivity showed strong perinuclear cytoplasmic staining without significant process labeling (Figure 2U black arrow, inset) typical of oligodendroglioma. Some MAP2 stained cells in MBP donor plasmid induced tumors displayed bi- or multi-polar processes typical of astroglial cells (Figure 2U grey arrow). In sum, the histological and immunohistochemical patterns observed in the tumors induced by MBP donor plasmids were distinct from those observed with the GFAP and CAG donor plasmids, and are most similar to human anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (WHO Grade III).

Expression of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors modifies tumor type

Next we addressed whether addition of neurogenic transcription factors, Neurogenin2 (Ngn2) and Neuronal Differentiation1 (NeuroD1) known to alter the fates of neural progenitors (32) would change tumor phenotype. We chose Ngn2 and NeuroD1 because they have been previously shown to block the differentiation of neural progenitors into astrocytes and to promote differentiation into neurons (32). We hypothesized that transcription factors with neuron promoting effects would either inhibit tumor formation, or result in the formation of tumors distinct from CAG donor plasmid induced tumors. Indeed, expression of either Ngn2 or NeuroD1 along with the CAG donor plasmids resulted in a distinct tumor type that we never observed with any of the three other tumor inducing plasmid combinations. Furthermore, animals transfected with the Ngn2 or NeuroD1 modifying plasmids showed earlier death and higher rates of death than the other tumorigenic plasmid conditions (Figure 3A) Log-rank tests showed animals transfected with Ngn2 or NeuroD1 modifying plasmids had significantly shorter survivals (P<0.0001) than animals transfected with CAG, GFAP or MBP donor plasmids (Figure 3A).

Upon postmortem analysis of cerebral tumors in Ngn2 and NeuroD1 donor plasmid conditions we encountered large cerebral tumors with highly irregular surfaces by 14 days of age (Figure 3B). Histologically these large tumors contained cells that were poorly differentiated and showed regions of extensive necrosis and proliferative features. The tumors contained prominent rhabdoid cellular elements demonstrated in H&E sections (black arrow in Figure 3H and L). The overall immunhistochemical profile indicated teratoid characteristics. Cells had characteristic‚“capping”-type expression patterns of Vimentin (black arrow in Figure 3I), and some cells were strongly positive for Actin (Figure 3J). There was also focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (Figure 3K). We also did not observe significant expression of cytokeratin (Lu-5 epitope). Nuclear expression of INI (hSNF5/SMARCB1) was preserved in cells in these tumors. While poorly differentiated, the tumors showed regions of focal expression of astroglial GFAP (Supplementary Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure 5C) and Vimentin positive processes (Figure 3I,M) as well as scattered positivity for the neuronal markers MAP2 (Supplementary Figure 4D, Supplementary Figure 5B) and synaptophysin (Supplementary Figure 4C). Intriguingly, synaptophysin positivity marked areas and clusters of tumor cells with cytologically neuronal features. The non-organoid distribution of respective elements argues against entrapped neurons. MAP2c expression appeared to reflect dendritic neuronal structures. In sum, the tumors induced by combining Ngn2 or NeuroD1 donor plasmids with the CAG donor plasmid histologlically most resembled atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) like tumors.

Hertwig et al (33) has reported that a panel of 7 signature genes can be used in error freely classification of three CNS tumors: glioma, PNET and ATRT. We therefore assessed the expression of this panel of 7 genes in the tumors induced by HRasV12/AKT in combination with Ngn2. We found significant up-regulation in the expression of 6 out of 7 genes in the tumors induced by HRasV12/AKT in and Ngn2 (Supplementary Figure 6). Among the 6 up-regulated genes, SPP1, which has been suggested as a diagnostic marker to distinguish ATRT from PNET and medulloblastoma (34) and as grade indicator of glioma (35), showed the greatest up-regulation (6.6 fold). The pattern of gene up-regulation combined with the histological features suggest that the tumors induced by HRasV12/AKT in combination with Ngn2 or NeuroD1 are ATRT-like tumors.

As the bHLH transfection conditions resulted in a unique and highly lethal tumor we next addressed whether this apparent phenotypic transformation from GBM to ATRT like tumors was due to a transient expression of bHLH factors in radial glia progenitors or to expression in tumor cells. The piggyBac transposon system allows for gating whether a transgene is integrated into a transfected cells or whether it remains episomal and is thus lost in cells that undergo subsequent proliferation (22). We substituted the Ngn2 donor plasmids used above with a plasmid, CAG-Ngn2, in which the CAG-Ngn2 transgene is not flanked by ITR sequences and so is not subject to transposase-mediated genomic integration (22). As a result, transgene expression from these episomal plasmids is lost in 1–2 cell divisions (22, 23). Addition of episomal CAG-Ngn2 was sufficient to produce tumors (Supplementary Figure 3, Figure 3C–E) with clusters of tumor cells expressing epithelia membrane antigen (Figure 3F) and isolated cells expressing cytokeratin (Lu-5 epitope, Figure 3G). Nuclear INI1 was also preserved (data not shown). Thus, transient expression of Ngn2 in radial glial progenitors and their immediate progeny is sufficient to produce ATRT-like tumors.

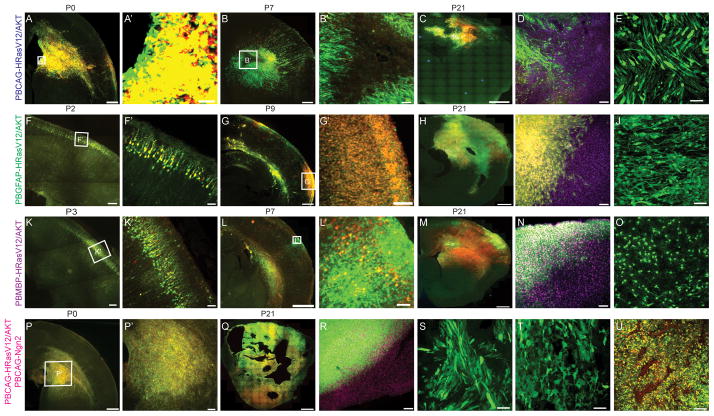

Distinct developmental patterns of tumors

The four tumor inducing conditions we describe above (CAG donor plasmid, GFAP donor plasmid, MBP donor plasmid, and CAG donor plasmid with a bHLH transcription factor modifying donor plasmid) each produced histologically distinct tumors when assessed at similar postnatal developmental time points. We next sought to address whether these differences might be reflected in differences in the developmental time course of each tumor type. As shown in figure 4A–E, we found that the CAG donor plasmid condition resulted in very early signs of abnormal cell proliferation with large aggregates of fluorescently labeled cells invading striatum and the ventricular and subventricular zones of neocortex by the day of birth (P0) in all animals examined (3/3). In contrast, aggregates of proliferative cells were not apparent in either the GFAP (0/3) or MBP donor plasmid (0/3) condition in the first few days after birth (P2–P3; Figure 4F,K), but instead normally differentiating neurons were apparent a few days after birth with only scattered cells outside of the neuronal cortical plate. By the end of the first postnatal week, masses of aberrantly proliferating cells appeared in both the MBP and GFAP donor plasmid conditions (Figure 4G, L) (3 out of 3 animals in MBP, GFAP donor transfected animals respectively). These masses were often of a single clonally labeled color and were present in areas centered within white matter and the sub-pial zone (Figure 4G,L). The time course of tumor growth was similar in the MBP and GFAP donor plasmid conditions, however as indicated in the histopathological analysis the morphology of cells in the two conditions differed in morphology by P21 (Figure 4H, I, J, and M, N, O). In spite of the delayed appearance of large tumors in the GFAP and MBP donor plasmid conditions relative to the CAG donor plasmid, the size of tumors in the MBP and GFAP donor plasmid conditions by P21 reached sizes larger than those in the CAG donor plasmid condition (Figure 4C, H, M). Finally, consistent with the early lethality and highly aggressive nature of the tumors induced by CAG donor plasmids with addition of Ngn2 modifying plasmid, the tumors in this condition (Figure 4, P–U) were obvious by the day of birth (4/4) and expanded rapidly into very large tumors with street-like necroses invading the entire cerebral hemisphere by three weeks after birth (7/7). The developmental patterns observed are consistent with when the promoters expressing the oncogenes are most active, the ubiquitous CAG promoter is strongly active early in progenitors while the GFAP and MBP promoters are most active latter in the lineage when glial cells begin differentiating.

Figure 4. Induced tumors show distinct developmental time course.

(A–E) Developmental time course for PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. (A) Densely packed cells were found in VZ/SVZ, striatum, neocortex and pia at P0. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in A′. (B) Necrosis at P7. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in B′. (C) Representative image of PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT transfected brain at P21. (D) Edge of PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. DAPI is shown in magenta. (E) Bipolar long spindle cells in PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT induced tumors. (F–J) Developmental time course for PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. (F) A representative section from a P2 brain transfected with PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in F′. (G) P9 section from PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT transfected brain. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in G′. (H) Representative image of PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT transfected brain at P21. (I) Edge of PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. DAPI is shown in magenta. (J) Bipolar pyramidal cells with long processes in tumors induced by PBGFAP-HRasV12/AKT (K–O) Developmental time course for PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. (K) A representative section from a P3 brain transfected with PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in K′. (L) P7 section from PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT transfected brain. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in L′. (M) Representative image of PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT transfected brain at P21. (N) Edge of PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT induced tumor. DAPI is shown in magenta. (O) Small round cells with short processes in tumors induced by PBMBP-HRasV12/AKT. (P) A representative image section from a brain transfected with PBCAG-Ngn2, PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT at P0. Magnified view of boxed area is shown in P′. (Q) A section from P21 animal showed tumor cells spreading whole cerebral hemisphere. (R) Edge of tumor induced by PBCAG-Ngn2, PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT. DAPI is shown in magenta. (S–T), Tumor cells frequently found in PBCAG-Ngn2, PBCAG-HRasV12/AKT induced tumors. (U) Extensive street like necrosis.

Scale bar: 1000μm in C, H, M and Q; 500μm in B, G, L and P; 200μm in A, F and K; 100μm in B′, D, G′ I, L′, N, P′, T, U; 50μm in A′ E, F′, K′J, O, S and T.

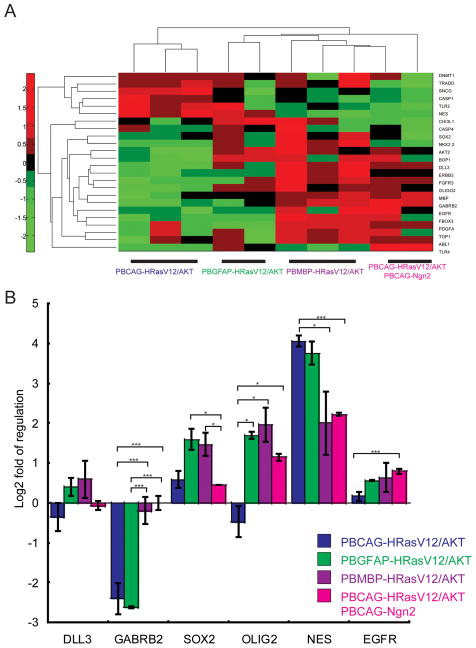

Gene expression differences in tumor types

The Cancer Genome Atlas research network (TCGA) identified 4 subtypes of glioblastoma multiforme subtypes by gene expression profiles and gene mutation (1). Through this analysis a group of 24 signature genes was identified that could be used to categorize the 4 subtypes (1). We therefore used expression levels of these 24 signature genes to further assess whether the four tumor patterns produced in our study could be distinguished based on the expression of this set of genes. To do this, we used q-PCR and unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis to compare and categorize the tumors produced by the four conditions. We found, consistent with the agreement in histopathological analysis, that the tumors produced by the CAG and GFAP donor plasmids clustered together in terms of expression of the 24 genes (Figure 5). The tumors that were most distinct in histopathology, those produced by the MBP donor plasmids and modified by the Ngn2 donor plasmids, differed in gene expression patterns relative both to each other and to the CAG and GFAP donor plasmid conditions (Figure 5). EGFR is frequently amplified and overexpressed in human GBMs; however, EGFR transcript was not prominent in all tumor types. This might be because Ras/AKT are downstream factors of EGFR pathway (15). We also found p53 was neither mutated nor deleted (data not shown) and p53 transcript showed about 2 fold of up regulation. Thus, the heterogeneity we find in tumors produced by differing promoter conditions and modifying transcription factor expression are also reflected in different gene expression patterns.

Figure 5. Induced tumors show different molecular signature.

(A) Unsupervised cluster analysis of qRT-PCR based gene expression data for 24 genes selected from Verhaak et al (1) across different donor plasmids induced tumors. Heat map shows fold change in gene expression in induced tumors relative to tumor free brain tissues. The 24 genes screened are listed on the left. Color scale represents fold changes of expression with red indicating up regulation and green indicating down regulation of gene expression. Gene expression across 4 conditions was shown in rows and expression of the whole set of 24 gene in each tumor sample was shown in columns. (B) Averaged fold of regulation for 6 representative genes selected from (A). Error bar indicates standard error of mean (SEM). (One way ANOVA, * indicates P<0.05, *** indicates P<0.01).

Discussion

Two, not mutually exclusive, explanations of tumor heterogeneity have been proposed (36). Overwhelming experimental and clinical evidence show that different genetic mutations result in different tumor types including different CNS tumor types (37). For example, Hertwig et al (33) showed that infection of postnatal mouse neural stem cells with viruses containing V12HRAS or c-MYC could result in formation of 3 different tumor types depending upon the combination and sequence in which oncogenes were introduced. Similarly, Jacques et al (38) showed that different combinations of conditional genetic deletions in p53, Rb and PTEN in mouse subventricular zone neural stem cells could induce formation of either PNET or glioma. Evidence for differing cell types being a source of CNS tumor heterogeneity has also been found (39–42). For example, transduction of mutationally stabilized N-Myc into neural stem cells from perinatal murine cerebellum and brain stem resulted in formation of medulloblastoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors, while N-Myc transduced into NSCs isolated from forebrain resulted in diffuse glioma tumors (41). As different neural progenitor types have different gene expression profiles that may modify tumor cell differentiation it seems likely that both cell of origin and differences in gene mutation contribute to tumor type diversity in the CNS (36). Our study indicates that in the developing neocortex cell populations of origin can contribute to tumor diversity, and moreover, that expression of non-oncogenic transcription factors expressed in the same population can also modify tumor type.

Although pediatric GBM shares histological similarities with adult GBM, they are now thought to be different entities with different molecular characteristics (2, 43). It has been shown, for example, that pediatric GBM display a spectrum of copy number variations distinct from adult GBM (44). Integrated molecular profiling experiments also reveal differences between pediatric and adult GBM. For example, IDH hotspot mutations are frequently found in adult high grade glioma but not in pediatric tumors (2, 43). In addition, whereas PDGFRA is the predominant target of focal amplification in pediatric high grade glioma, in adult glioblastoma EGFR is the most common target (43). Moreover, histone H3.3 mutations are frequently found in pediatric GBM while they are absent in adult GBM (2, 45). The cell of origin of pediatric GBM is unknown and might be different from adult GBM as well. We have used the CAG donor plasmids to induce GBM which appeared as early as P7 in the rat and shows necrotic areas as early as at P4 a developmental time period in the precocial rat that corresponds to the neonatal period in human. Future experiments will be needed to determine whether the early arising tumors modeled in this system are more similar to pediatric or adult GBM in their molecular identity and cell of origin.

Our study indicates that the cell of mutation for both ATRT like and GBM can be radial glial cells of embryonic neocortex. The in utero electroporation method we used targets radial glia and radial neural progenitor cells that line the lateral ventricles of the lateral forebrain. This population of progenitors at the ventricular surface of E14/15 rat forebrain contains sub-populations of progenitors capable of generating neurons of different types, and primarily glia or primarily neurons (23). We used the ubiquitous CAG donor plasmid to induce expression of HRasV12 and AKT immediately in the radial progenitor population. Ngn2 or NeuroD1 expressed by the same immediately active promoter was sufficient to change the tumor type generated. The tumor difference was apparent as early as the day of birth, approximately one week after induced gene expression. We also found that transient expression of Ngn2 (by a non-donor episomal plasmid) in radial glia was sufficient to produce ATRT like tumors. The effectiveness of transient Ngn2 expression, in combination with previous findings that Ngn2 or NeuroD1 expressed in glioma cells induces cell death and neuronal differentiation without changing tumor type (46, 47) supports the idea that Ngn2 and NeuroD1 acts in early stage radial progenitors to change the type of tumor generated. We have co-expressed Ngn2 with GFAP donor plasmids and found the resulted tumors were similar to tumors induced by GFAP donor plasmids alone. But we did found rhabdoidal cells in the resulted tumors (data not shown). However, the results have to be interpreted with caution since the mouse GFAP promoter fragment is also active in radial glia. In the future, combining Ngn2 with MBP donor plasmids may distinguish the time of action of Ngn2.

Loss of function in the INI1 gene is believed to be a significant cause of ATRT in humans (48). INI1 knockout mice develop tumors but these do not appear to be ATRT (49). Hertwig et al (33) showed that transplantation of NSC/NPCs serially infected with c-MYC and V12HRAS could generate ARTR like tumors with gene expression profiles similar to human ATRT suggesting that in rodent models additional mutation types can lead to ATRT. Similarly, we demonstrated in this study that ATRT like tumors are generated by HRasV12 and AKT transfection of neocortical radial glia, but only when co-expressed with the bHLH transcription factors Ngn2 or NeuroD1, two genes that on their own are non-oncogenic. This underscores the strong possibility that tumor type diversity may be influenced not only by the cell of mutation but also by the specific molecular context present in that cell.

Our current results also show that the GFAP and MBP promoter-active populations in the radial glia lineage generate tumors with different molecular and histological features. Interestingly, all cell types are labeled by the GFAP and MBP donor plasmids, but yet the tumor types generated were consistently different in histology and molecular signature. This may suggest that tumor diversity is determined by the predominant cell type in a population that undergoes transformation. By mixing the GFAP and MBP donor plasmids in future experiments and tracking their clonal expansion we may be able to distinguish whether one tumor cell population is dominant over the other.

Several attributes of piggyBac transposon system demonstrated here make this model potentially useful for a variety of novel applications in tumor biology. The main advantage of the piggyBac IUE method is that it allows for introduction of multiple transgenes. In this study, for example, we simultaneously introduced a transposase helper plasmid to target stable transgenesis in GLAST positive cells, two oncogene expressing donor plasmids with their own promoters, 3 fluorescent reporter genes (Figure 1, 2 and 3), and a transcription factor. The high coexpression efficiency allowed us to direct expression in different subpopulations in sequence, introduce a clonal labeling method, and a modifying transcription factor. This functionality should make this approach a useful platform for screening potential modifiers of tumor development and for determining further how genetic modifiers alter tumor development.

Supplementary Material

Implications.

A novel CNS tumor model reveals that oncogenic events occurring in disparate cell types and/or molecular contexts leads to different tumor types; these findings shed light on the sources of brain tumor heterogeneity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Akiko Nishiyama for kindly providing NG2 and CC1 antibody. We also would like to thank the followings for their generosity sharing their constructs with us: Dr. William Sellers for pcDNA3 Myr HA Akt1 construct; Dr. Inder Verma for pTomo construct.

Grant support

This work is supported by NIH grants: RO1HD055655 and R01MH056524 for Joseph LoTurco.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haque T, Faury D, Albrecht S, Lopez-Aguilar E, Hauser P, Garami M, et al. Gene expression profiling from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors of pediatric glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6284–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faury D, Nantel A, Dunn SE, Guiot MC, Haque T, Hauser P, et al. Molecular profiling identifies prognostic subgroups of pediatric glioblastoma and shows increased YB-1 expression in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1196–208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson AI, Petritsch C, Swartling FJ, Itsara M, Sim FJ, Auvergne R, et al. Non-stem cell origin for oligodendroglioma. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:669–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Sage JC, Miller MR, Verhaak RG, Hippenmeyer S, Vogel H, et al. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell. 2011;146:209–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhrbom L, Hesselager G, Nister M, Westermark B. Induction of brain tumors in mice using a recombinant platelet-derived growth factor B-chain retrovirus. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland EC, Hively WP, DePinho RA, Varmus HE. A constitutively active epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with disruption of G1 cell-cycle arrest pathways to induce glioma-like lesions in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3675–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland EC, Celestino J, Dai C, Schaefer L, Sawaya RE, Fuller GN. Combined activation of Ras and Akt in neural progenitors induces glioblastoma formation in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:55–7. doi: 10.1038/75596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhrbom L, Dai C, Celestino JC, Rosenblum MK, Fuller GN, Holland EC. Ink4a-Arf loss cooperates with KRas activation in astrocytes and neural progenitors to generate glioblastomas of various morphologies depending on activated Akt. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5551–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hambardzumyan D, Amankulor NM, Helmy KY, Becher OJ, Holland EC. Modeling Adult Gliomas Using RCAS/t-va Technology. Transl Oncol. 2009;2:89–95. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmen SL, Williams BO. Essential role for Ras signaling in glioblastoma maintenance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8250–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindberg N, Kastemar M, Olofsson T, Smits A, Uhrbom L. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can act as cell of origin for experimental glioma. Oncogene. 2009;28:2266–75. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcantara Llaguno S, Chen J, Kwon CH, Jackson EL, Li Y, Burns DK, et al. Malignant astrocytomas originate from neural stem/progenitor cells in a somatic tumor suppressor mouse model. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marumoto T, Tashiro A, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Scadeng M, Soda Y, Gage FH, et al. Development of a novel mouse glioma model using lentiviral vectors. Nat Med. 2009;15:110–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedmann-Morvinski D, Bushong EA, Ke E, Soda Y, Marumoto T, Singer O, et al. Dedifferentiation of neurons and astrocytes by oncogenes can induce gliomas in mice. Science. 2012;338:1080–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1226929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiesner SM, Decker SA, Larson JD, Ericson K, Forster C, Gallardo JL, et al. De novo induction of genetically engineered brain tumors in mice using plasmid DNA. Cancer Res. 2009;69:431–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei L, Sonabend AM, Guarnieri P, Soderquist C, Ludwig T, Rosenfeld S, et al. Glioblastoma models reveal the connection between adult glial progenitors and the proneural phenotype. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen F, LoTurco J. A method for stable transgenesis of radial glia lineage in rat neocortex by piggyBac mediated transposition. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;207:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddiqi F, Chen F, Aron AW, Fiondella CG, Patel K, Loturco JJ. Fate Mapping by PiggyBac Transposase Reveals That Neocortical GLAST+ Progenitors Generate More Astrocytes Than Nestin+ Progenitors in Rat Neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(2):508–20. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusa K, Rad R, Takeda J, Bradley A. Generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent mouse stem cells by the piggyBac transposon. Nat Methods. 2009;6:363–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LoTurco J, Manent JB, Sidiqi F. New and improved tools for in utero electroporation studies of developing cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19 (Suppl 1):i120–5. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Y, Lin C, Wang X. PiggyBac transgenic strategies in the developing chicken spinal cord. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida A, Yamaguchi Y, Nonomura K, Kawakami K, Takahashi Y, Miura M. Simultaneous expression of different transgenes in neurons and glia by combining in utero electroporation with the Tol2 transposon-mediated gene transfer system. Genes Cells. 2010;15:501–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guha A, Feldkamp MM, Lau N, Boss G, Pawson A. Proliferation of human malignant astrocytomas is dependent on Ras activation. Oncogene. 1997;15:2755–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Vazquez F, Batt DB, Perera S, Roberts TM, et al. Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2110–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centanni TM, Booker AB, Sloan AM, Chen F, Maher BJ, Carraway RS, et al. Knockdown of the Dyslexia-Associated Gene Kiaa0319 Impairs Temporal Responses to Speech Stimuli in Rat Primary Auditory Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht028.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schick V, Majores M, Koch A, Elger CE, Schramm J, Urbach H, et al. Alterations of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway components in epilepsy-associated glioneuronal lesions. Epilepsia. 2007;48 (Suppl 5):65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schick V, Majores M, Engels G, Hartmann W, Elger CE, Schramm J, et al. Differential Pi3K-pathway activation in cortical tubers and focal cortical dysplasias with balloon cells. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:165–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber K, Thomaschewski M, Warlich M, Volz T, Cornils K, Niebuhr B, et al. RGB marking facilitates multicolor clonal cell tracking. Nat Med. 2011;17:504–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Q, Miskimins WK, Miskimins R. Cloning and characterization of the rat myelin basic protein gene promoter. Gene. 2003;313:161–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai L, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. Misexpression of basic helix-loop-helix genes in the murine cerebral cortex affects cell fate choices and neuronal survival. Development. 2000;127:3021–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hertwig F, Meyer K, Braun S, Ek S, Spang R, Pfenninger CV, et al. Definition of genetic events directing the development of distinct types of brain tumors from postnatal neural stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3381–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao CL, Chiou SH, Ho DM, Chen YJ, Liu RS, Lo CW, et al. Elevation of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid osteopontin levels in patients with atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. American journal of clinical pathology. 2005;123:297–304. doi: 10.1309/0ftkbkvnk4t5p1l1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toy H, Yavas O, Eren O, Genc M, Yavas C. Correlation between osteopontin protein expression and histological grade of astrocytomas. Pathology oncology research: POR. 2009;15:203–7. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visvader JE. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 2011;469:314–22. doi: 10.1038/nature09781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sieber OM, Tomlinson SR, Tomlinson IP. Tissue, cell and stage specificity of (epi)mutations in cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:649–55. doi: 10.1038/nrc1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacques TS, Swales A, Brzozowski MJ, Henriquez NV, Linehan JM, Mirzadeh Z, et al. Combinations of genetic mutations in the adult neural stem cell compartment determine brain tumour phenotypes. Embo J. 2010;29:222–35. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson P, Tong Y, Robinson G, Thompson MC, Currle DS, Eden C, et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature. 2010;468:1095–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ince TA, Richardson AL, Bell GW, Saitoh M, Godar S, Karnoub AE, et al. Transformation of different human breast epithelial cell types leads to distinct tumor phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swartling FJ, Savov V, Persson AI, Chen J, Hackett CS, Northcott PA, et al. Distinct neural stem cell populations give rise to disparate brain tumors in response to N-MYC. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:601–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown K, Strathdee D, Bryson S, Lambie W, Balmain A. The malignant capacity of skin tumours induced by expression of a mutant H-ras transgene depends on the cell type targeted. Curr Biol. 1998;8:516–24. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, Adamowicz-Brice M, Zhang J, et al. Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bax DA, Mackay A, Little SE, Carvalho D, Viana-Pereira M, Tamber N, et al. A distinct spectrum of copy number aberrations in pediatric high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3368–77. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482:226–31. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao J, He H, Zhou K, Ren Y, Shi Z, Wu Z, et al. Neuronal transcription factors induce conversion of human glioma cells to neurons and inhibit tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guichet PO, Bieche I, Teigell M, Serguera C, Rothhut B, Rigau V, et al. Cell death and neuronal differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells induced by neurogenic transcription factors. Glia. 2012;61:225–39. doi: 10.1002/glia.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biegel JA. Molecular genetics of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klochendler-Yeivin A, Fiette L, Barra J, Muchardt C, Babinet C, Yaniv M. The murine SNF5/INI1 chromatin remodeling factor is essential for embryonic development and tumor suppression. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:500–6. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.