Abstract

Many patients present to the emergency department complaining of a sore or stiff neck and lateral flexion of the neck with contralateral rotation. Under the pressure of the breaching time and busy shifts some of the patients are discharged to the care of their general practitioners without adequate investigations. While most of the cases are due to benign causes, torticollis can be due to many congenital and acquired pathologies, some of which may need further investigation and urgent management. Atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS), tumours of the base of the skull and infections are among these causes. Delayed diagnosis may lead to worsening neurology and complicate the management. We report a case of a 5-year-old girl who presented to our fracture clinic with a fractured clavicle and torticollis; her subsequent investigations confirmed the diagnosis of AAS. Our patient responded to non-operative treatment and improved with no neurological complications.

Background

Atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS) is a serious condition that is associated with neurological complications such as cervical myelopathy, vertebrobasilar insufficiency symptoms and may lead to paralysis or sudden death due to cord and brain stem compression.

Bell et al reported upper respiratory tract infection as a cause of Grisel's syndrome. The hyperaemia associated with upper respiratory tract infections has been attributed to the laxity of the transverse and alar ligaments leading to AAS.1

The outcomes of treatment are affected by the duration of symptoms, and chronic missed cases may need fusion in situ in some cases.

We hope that consideration of cases such as the one we describe here will raise awareness of this important differential diagnosis among medical staff involved in the assessment and management of patients with torticollis.

Case presentation

A 5-year-old girl fell while playing in school and landed on both hands. She presented to the emergency department with neck and shoulder pain; her X-rays showed a fracture of the right clavicle and she was referred to our fracture clinic. She recovered from a viral upper respiratory tract infection a week ago and is otherwise well.

The patient lives with her parents and is up-to-date with her immunisations.

On examination in the clinic, she was afebrile with no palpable lymph nodes. She was tender in her mid-clavicle in keeping with the emergency department diagnosis. Her X-rays confirmed a mid-clavicle fracture.

The surgeon in the clinic noticed that the patient was not moving her neck; there was also minimum tenderness in the back of her neck and her neurological examination was normal.

The mother gave a history of cough and sneezing 2 weeks prior to the presentation suggestive of an upper respiratory tract infection, otherwise she was fit and well.

The patient lives with her mother and father, is up-to-date with her immunisation and has no family history of similar condition.

Investigations

Inflammatory markers were within normal range.

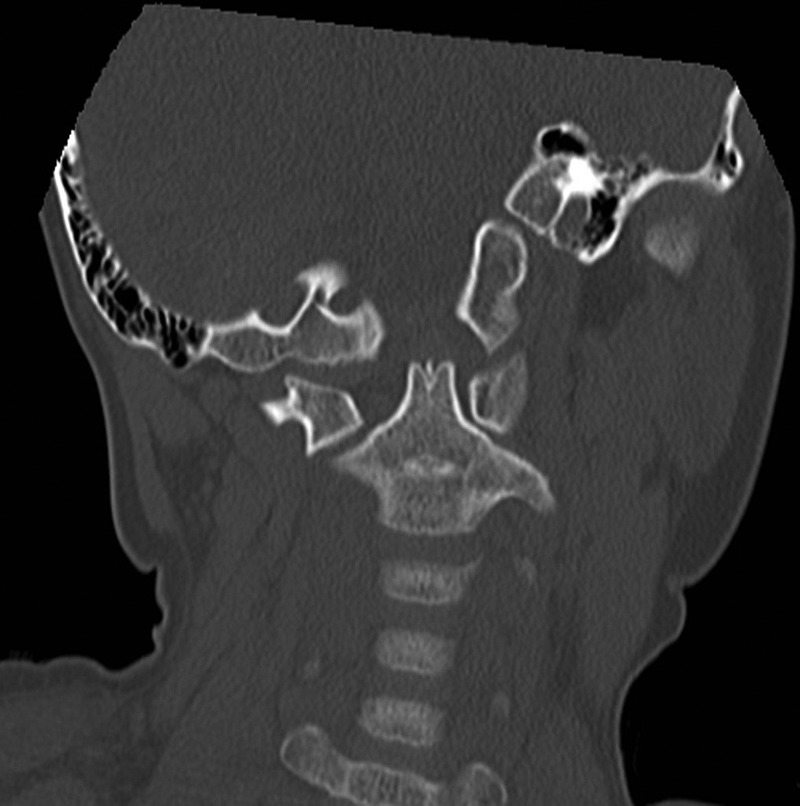

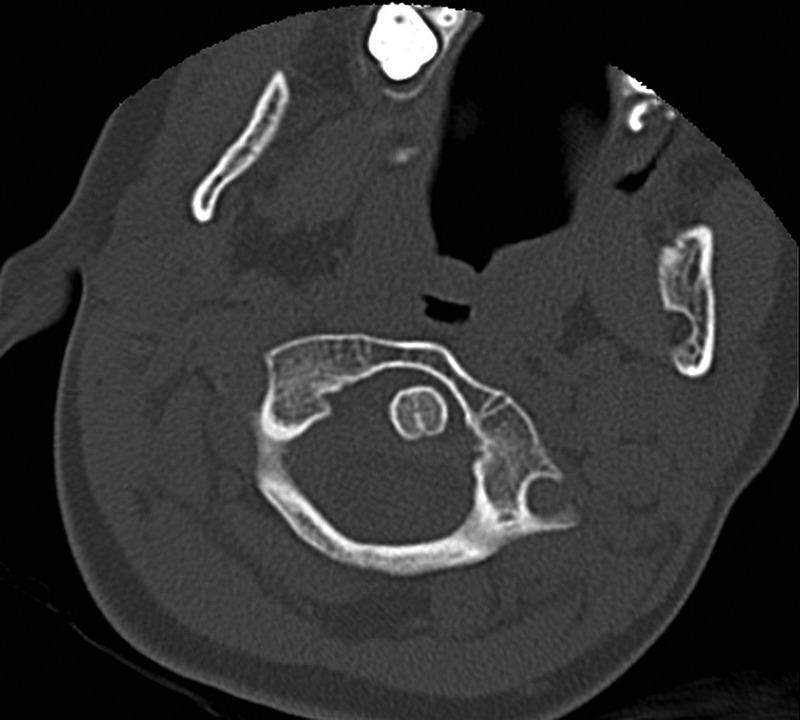

▸ CT cervical spine: The C2 vertebral body is rotated in comparison with the C1 vertebral body. The odontoid peg no longer lies centrally and is seen to be closer to the left side of the C1 arch than the right side (figures 1 and 2).

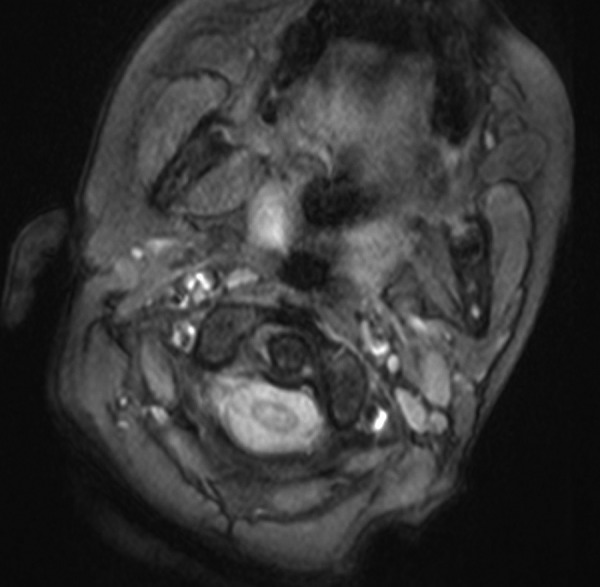

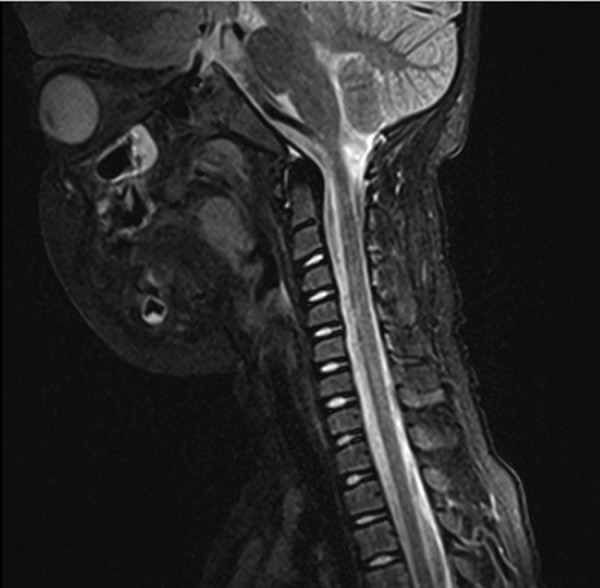

MRI cervical spine: Comparison with the recent CT evaluation reveals the magnitude of the rotatory deformity at the C1–2 level to be broadly similar but the appearances of the marked anterior translation of the right C1 lateral mass relative to the C2 facet are now only subtle. The atlanto-odontoid relationships now appear more normal and the off-centre placement of the odontoid appears less marked (figures 3 and 4).

Repeat CT cervical spine after 3 days: In comparison with the previous CT, there is now good alignment of the C1 related to C2. Very mild right-sided offset of the odontoid related to the lateral masses persists. The odontoid to C1 arch distance is reduced to now normal appearance (figure 5).

Figure 1.

CT of the cervical spine, bone window, coronal view showing the odontoid peg no longer lies centrally and is seen to be closer to the left side of the C1 arch than the right side and the C2 vertebral body is rotated in comparison with the C1 vertebral body.

Figure 2.

CT of the cervical spine, bone window, axial view confirming the atlantoaxial subluxation.

Figure 3.

MRI, axial view of the atlantoaxial joint.

Figure 4.

MRI, sagittal view of the cervical spine.

Figure 5.

Follow-up CT scan showing the reduced atlantoaxial joint.

Differential diagnosis

Traumatic AAS

Grisel's syndrome

Treatment

For this case, initial treatment involved analgesia and a soft collar. The patient underwent MRI with sedation within a few days of admission and further imaging confirmed satisfactory reduction of the subluxation.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient had complete symptomatic relief with no neurological sequelae or recurrence in her 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

Torticollis—also known as Cock Robin position––is lateral flexion of the neck with contralateral rotation. It is a common sign that can present with congenital and acquired pathologies. AAS, sternocleidomastoid anomalies, infections (Grisel's syndrome), medication (such as antipsychotics) and tumours of the base of the skull are among the known causes for torticollis.2 3

Around 50% of the cervical rotation happens at the atlantoaxial articulation, hence the atlas has a wider canal to accommodate the transitional displacement associated with the rotation. Steele law of thirds divided the 3 cm space into three-thirds: spinal cord (1 cm)+odontoid process (1 cm)+free space (1 cm); the anterior displacement must not exceed 1 cm.

AAS usually refers to loss of ligamentous stability. It can be flexion/extension, distraction and rotation, leading to anterior displacement of the peg and therefore compression of the cord.

Patients may suffer from pain, occipital neuralgia and occasionally vertebrobasilar insufficiency symptoms. It is associated with Down syndrome, Morquio syndrome, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), trauma (atlas fractures), infections, degenerative and transverse ligament injuries.1 3 4

AAS is a rare condition that needs to be investigated, diagnosed then treated urgently. The outcomes of treatment are affected by the delay in diagnoses as missed cases or cases which are treated late are more likely to need operative intervention and/or suffer from neurological consequences; hence, a high degree of suspicion with thorough history and careful examination for all cases of torticollis is required.

Bell et al reported the association with upper respiratory tract infections in a case of AAA following syphilitic ulceration of the pharynx. Grisel's syndrome is usually seen in cases of head and neck infections such as pharyngitis and adenotonsillitis and otitis media; it is also observed after some neck procedure such as tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy and mastoidectomy. The hyperaemia associated with upper respiratory tract infections has been attributed to the laxity of the transverse and alar ligaments leading to AAA.1

The Fielding and Hawkins classification is one of the many classification systems that can help in the interpretation of the radiological investigations.4 The cases can be subdivided according to the degree of displacement into:

Type I: Simple rotation displacement

Type II: antero-posterior (AP) displacement 3–5 mm

Type III: AP displacement more than 5 mm

Type IV: Posterior displacement

Treatment options are affected by the duration of symptoms. Münch and others reported treatment of acute cases non-operatively, that includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, benzodiazepines and a soft collar. Non-responding cases can be treated by Halter traction or closed reduction followed by Halo traction as Chechik reported in his case series.1 5

Fusion can be the treatment of choice in recurrent cases or those unstable after removal of traction with neurological involvement; some chronic cases may require fusion in situ.6

Learning points.

Always suspect atlantoaxial subluxation in cases of torticollis.

Dynamic CT scan is the gold standard in investigation.

Treatment in most of the cases is non-operative using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, soft collar and sedation if needed.

Cases with delayed diagnosis and treatment are more likely to need operative interventions and may suffer from serious neurological complications.

Footnotes

Contributors: EB was involved in data collection, literature search and writing the paper. SD was involved in data collection. PL was senior author and treating surgeon.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dagtekin A, Kara E, Vayisoglu Y, et al. The importance of early diagnosis and appropriate treatment in Grisel's syndrome: report of two cases. Turk Neurosurg 2011;21:680–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beier AD, Vachhrajani S, Bayerl SH, et al. Rotatory subluxation: experience from the Hospital for Sick Children. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2012;9:144–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreur M, Reynolds NC, Ma J. Torticollis, 2012. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1152543-overview

- 4.Sobolewski BA, Mittiga MR, Reed JL, et al. Atlantoaxial rotary subluxation after minor trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008;24:852–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Münch C, Linhart W, Storck A, et al. Treatment of traumatic rotatory atlanto-axial subluxation in childhood. Case report and literature review. Unfallchirurg 2005;108:987–90 [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chechik O, Wientroub S, Danino B, et al. Successful conservative treatment for neglected rotatory atlantoaxial dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop 2013;33:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]