Using gene editing, the authors have generated human cell lines lacking Dicer and found that these cells are essentially devoid of microRNAs. However, transfected synthetic microRNA duplexes rescue microRNA function and permit the identification of the mRNA targets of single microRNAs in the absence of endogenous microRNAs. The authors also show that the Drosophila Dicer1 protein, together with its cofactor Loqs-PB, is able to rescue human pre-microRNA processing, indicating strong functional conservation.

Keywords: Dicer, microRNAs, RNA interference, RISC, post-transcriptional regulation

Abstract

We have used genome editing to generate inactivating deletion mutations in all three copies of the dicer (hdcr) gene present in the human cell line 293T. As previously shown in murine ES cells lacking Dicer function, hDcr-deficient 293T cells are severely impaired for the production of mature microRNAs (miRNAs). Nevertheless, RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) present in these hDcr-deficient cells are readily programmed by transfected, synthetic miRNA duplexes to repress mRNAs bearing either fully or partially complementary targets, including targets bearing incomplete seed homology to the introduced miRNA. Using these hDcr-deficient 293T cells, we demonstrate that human pre-miRNA processing can be effectively rescued by ectopic expression of the Drosophila Dicer 1 protein, but only in the presence of the PB isoform of Loquacious (Loqs-PB), the fly homolog of the hDcr cofactor TRBP. In contrast, Drosophila Dicer 2, even in the presence of its cofactors Loqs-PD and R2D2, was unable to support human pre-miRNA processing. Interestingly, although ectopic Drosophila Dicer 1/Loqs-PB or hDcr both rescued pre-miRNA processing effectively in these hDcr-deficient cells, there were significant differences in the ratio of the miRNA isoforms that were produced, especially in the case of miR-30 family members, and we also noted differences in the relative expression level of miRNAs vs. passenger strands for a subset of human miRNAs. These data demonstrate that the mechanisms underlying the accurate processing of pre-miRNAs are largely, but not entirely, conserved between mammalian and insect cells.

INTRODUCTION

In the canonical mammalian microRNA (miRNA) processing pathway, the miRNA is initially transcribed by RNA polymerase II as a long primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) precursor in which the mature miRNA forms the upper part of the stem of an ∼80-nt stem–loop structure (Cullen 2004). This stem–loop is bound by the microprocessor, consisting of the RNase III enzyme Drosha and its cofactor DGCR8, which cleaves the stem ∼22 bp from the terminal loop, leaving an ∼2-nt 3′ overhang (Denli et al. 2004; Gregory et al. 2004; Han et al. 2004). The resultant pre-miRNA hairpin intermediate is transported to the cytoplasm by Exportin 5 (Yi et al. 2003), where it encounters a second RNase III enzyme, Dicer. Dicer, acting in concert with its double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding cofactor TRBP, cleaves the pre-miRNA ∼22 bp away from its base to remove the terminal loop and leave a second ∼2-nt 3′ overhang (Chendrimada et al. 2005). One strand of the resultant miRNA duplex intermediate is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), consisting minimally of one of the four mammalian Argonaute (Ago) proteins Ago1 through Ago4, while the passenger strand is degraded (Hammond et al. 2001; Khvorova et al. 2003; Su et al. 2009). The miRNA then guides RISC to mRNAs bearing fully or partially complementary target sites, resulting in their degradation and/or translational repression. The key feature of most functional mRNA targets is that they are fully complementary to the miRNA “seed” region, extending from miRNA position 2 to position 7 or, preferably, position 8 (Brennecke et al. 2005; Lewis et al. 2005). However, complementary sequences outside of the miRNA seed have been proposed to facilitate miRNA function and RNA targets lacking full seed complementarity, here referred to as noncanonical targets, have been reported (Brennecke et al. 2005; Grimson et al. 2007; Shin et al. 2010).

While there have been a number of reports describing cellular or viral miRNAs that arise via maturation pathways that do not involve Drosha (Berezikov et al. 2007; Ruby et al. 2007; Bogerd et al. 2010; Cazalla et al. 2011), only a single cellular miRNA, miR-451, has been identified that is expressed in the absence of Dicer (Cheloufi et al. 2010; Cifuentes et al. 2010). Analysis of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem (ES) cells, generated by homologous recombination, has indeed confirmed that cellular miRNA expression is blocked (Murchison et al. 2005; Calabrese et al. 2007; Chong et al. 2010) and has also revealed that miRNAs are required for the ability of ES cells to undergo differentiation (Bernstein et al. 2003; Kanellopoulou et al. 2005). Therefore, it is not possible to generate Dicer-deficient somatic murine cells from Dicer-deficient ES cells, although Dicer-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), generated by conditional deletion using Cre-recombinase, have been recently reported (Chong et al. 2010; Frohn et al. 2012; Smibert et al. 2013). The difficulty of manipulating ES cells and MEFs in culture has, however, so far largely restricted the analysis of these Dicer-negative cells to the demonstration of differences in their mRNA and small RNA expression profiles. Moreover, no human cell lines lacking hDcr have so far been reported.

Here, we report the use of genome editing using transcription activator-like endonucleases (TALENs) (Christian et al. 2010; Mahfouz et al. 2011; Miller et al. 2011) to generate a derivative of the readily manipulable human cell line 293T entirely lacking hDcr function (NoDice cells). While these cells lack endogenous miRNA expression, and are unable to process pre-miRNAs into mature miRNAs, they express close to normal levels of Ago2 which can be efficiently programmed using exogenous, synthetic miRNA duplexes. Using this approach, we have identified RNA target sites bound by either human miR-155 or by Kaposi's sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) miR-K11, which share an identical seed region, but otherwise differ in sequence (Gottwein et al. 2007; Skalsky et al. 2007). Some of these target sites are effectively bound by miR-155 but not by miR-K11, and vice versa, and this discrimination is clearly reflective of target RNA complementarity to regions outside of the miRNA seed. We also demonstrate that mature miRNA production can be rescued in human NoDice cells by ectopic expression of the Drosophila Dicer1 (dDcr1) protein, but only when the loquacious PB (loqs-PB) cofactor is also coexpressed (Saito et al. 2005; Hartig et al. 2009). In contrast, expression of Drosophila Dicer2 (dDcr2) did not rescue human miRNA processing, even in the presence of the dDcr2 cofactors loqs-PD and R2D2 (Nishida et al. 2013). The human NoDice cell lines therefore represent a novel and facile tool to analyze the biogenesis and targeting potential of miRNAs.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of Dicer-deficient human cells

To generate Dicer-deficient human cells, we constructed expression plasmids encoding a pair of transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) proteins (Christian et al. 2010; Mahfouz et al. 2011; Miller et al. 2011) designed to cleave the human dicer (hdcr) gene at nucleotide (nt) 1095 of the hDcr cDNA sequence, in coding exon 11. The TALENs were epitope tagged using a FLAG tag and their expression was readily detectable in transfected cells by Western blot (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Cotransfection of the TALEN expression vectors into 293T cells, along with an indicator construct containing the entire predicted target sequence for the TALEN pair inserted upstream of, and in frame with, a green fluorescent protein (gfp) indicator gene, resulted in the specific loss of GFP expression (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Therefore, as these TALENs were clearly both expressed and active in cultured cells, we next asked whether they would allow the generation of an hdcr-deficient derivative of the human cell line 293T. For this purpose, we transfected 293T cells with expression vectors encoding both TALEN proteins and then isolated and expanded single-cell clones for further analysis. A series of 25 independent clonal cell lines were obtained and eight of these clones (32%) appeared to have entirely lost hDcr expression, as determined by Western blot using an antibody specific for the hDcr carboxy-terminal region (Fig. 1A; data not shown). Two 293T cell clones, NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25), were selected for further analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of the NoDice cells. (A) Western analysis of endogenous hDcr expression in WT 293T cells and the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell lines. (B) Northern analysis of pre-miR-155 and mature miR-155 expression in WT 293T cells and NoDice(2-20) or NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with a pri-miR-155 expression vector. In lanes 4 and 6, the NoDice cells were also cotransfected with an hDcr expression plasmid. (C) Indicator assay measuring the ability of a pri-miR-155 expression plasmid to repress an indicator plasmid consisting of RLuc linked to a 3′ UTR containing two artificial miR-155 target sites. The cells analyzed include WT 293T cells and the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell lines. Data are normalized to the level of RLuc activity seen in each cell type in the absence of pri-miR-155. Average of three experiments with SD indicated. (D) Growth curve of WT 293T cells, NoDice(2-20) cells, and NoDice(4-25) cells. These data indicate that the doubling time has increased from ∼1.3 d for WT 293T to ∼2.5 d for both NoDice cell types.

To test the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell lines for hDcr function, we introduced a previously described expression vector (Gottwein et al. 2007) encoding human pri-miR-155, which is not normally expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 1B, lane 1). This vector gives rise to readily detectable levels of mature miR-155, and low but detectable levels of pre-miR-155, after introduction into the parental 293T cells (Fig. 1B, lane 2). In contrast, in both the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell line, ectopic pri-miR-155 expression resulted in overexpression of the pre-miR-155 intermediate, but no detectable mature miR-155 (Fig. 1B, lanes 3,5). However, cotransfection of an expression plasmid encoding an hDcr cDNA resulted in the rescue of mature miR-155 production in both cell lines (Fig. 1B, lanes 4,6). As expected from these data, the transfected pri-miR-155 expression plasmid induced the efficient repression of a cotransfected Renilla luciferase (RLuc)-based indicator construct bearing two complementary target sites for miR-155, introduced into the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of rluc, when the parental 293T cells were used (Fig. 1C). In contrast, cotransfection of the same pri-miR-155 expression plasmid and miR-155 indicator plasmid did not result in a significant level of inhibition of RLuc expression in either of the two NoDice cell lines (Fig. 1C).

The NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell lines appeared similar to the parental 293T cells except that they clearly proliferated more slowly (Fig. 1D), as also seen previously for Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem (ES) cells (Murchison et al. 2005). Analysis of the genomic hdcr gene sequence in the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) cell lines revealed that 293T cells are triploid for the hdcr gene and that each copy of the gene bore different, overlapping deletion mutations adjacent to the predicted TALEN cleavage site in hdcr exon 11 (Supplemental Fig. S2). The observed deletions were each unique, including deletions of 16, 14, and 529 bp in NoDice(4-25) and of 14, 14, and 175 bp in NoDice(2-20). Of note, the three 14-bp deletions were each different in terms of the hdcr DNA sequence that was lost (Supplemental Fig. S2). Moreover, it was apparent that reversion to the wild-type hdcr sequence, due to homologous recombination, would not be possible in either the NoDice(4-25) or NoDice(2-20) cell line.

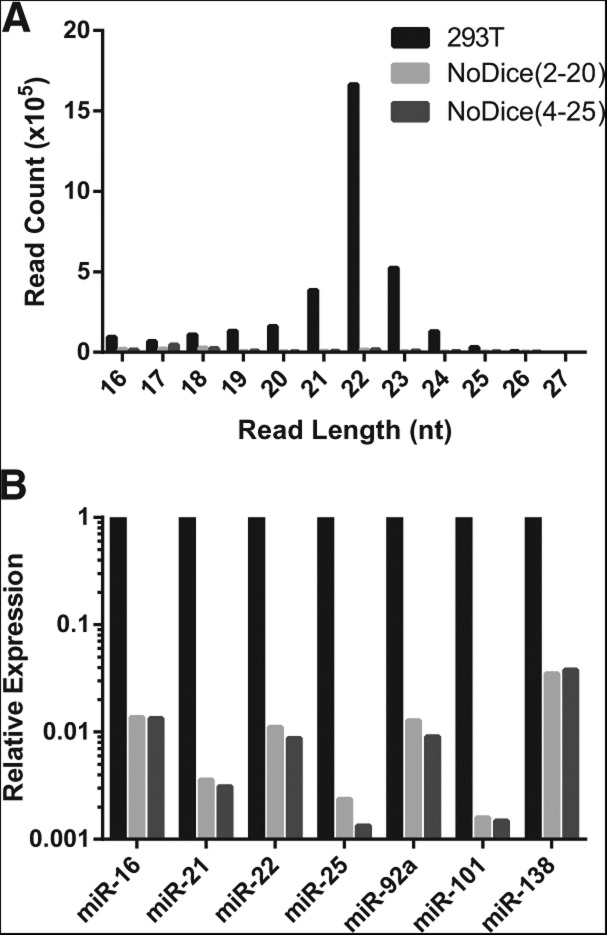

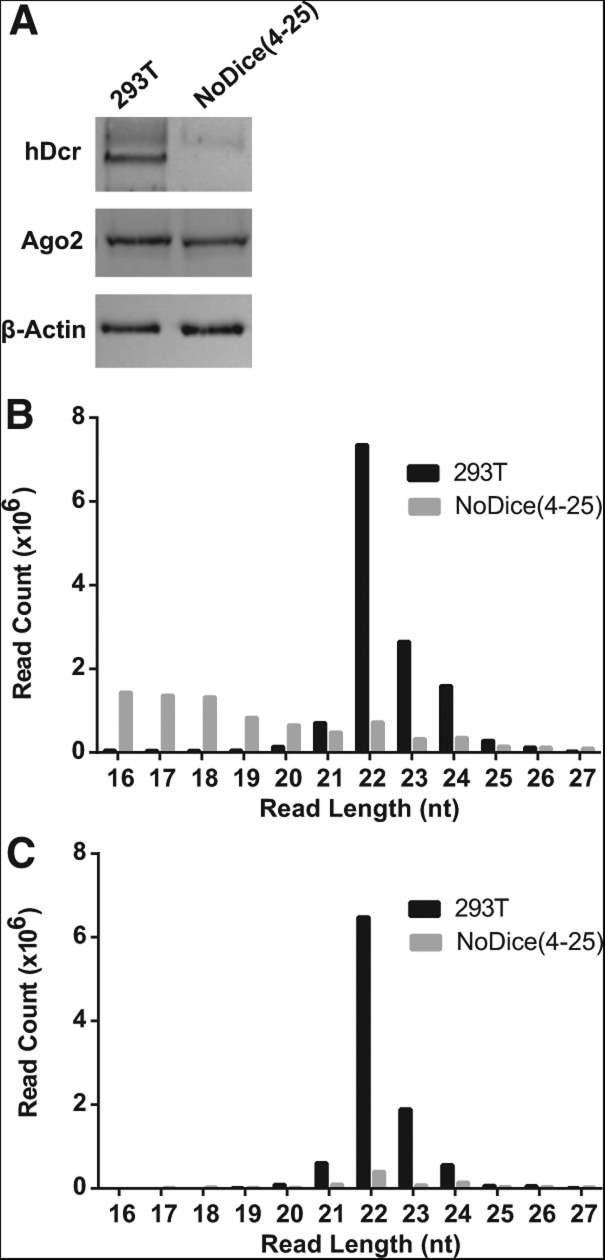

We next addressed the small RNA expression profile of the hDcr-deficient cells, initially using deep sequencing of total small (16–27-nt long) RNAs. As shown in Figure 2A, the hDcr knockout cells were deficient for the expression of cellular miRNAs, though some pre-miRNA fragments, primarily in the 16–20 nt size range, could be detected. RT-PCR analysis of seven miRNAs that are naturally expressed in the parental 293T cell also revealed that their expression had declined by ∼100-fold (Fig. 2B). The remaining cellular miRNA-specific signal likely results from the low level of pre-miRNA degradation products also noted in Figure 2A. Nevertheless, we were curious to see if this low level of detectable pre-miRNA derived RNAs were actually loaded into RISC. Although it has been previously reported that loss of Dicer expression, and hence loss of miRNA expression, results in the destabilization of Ago2 in mouse ES cells or murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) (Martinez and Gregory 2013; Smibert et al. 2013), loss of hDcr expression in human 293T cells had at most a modest effect on the steady state level of Ago2 protein expression (Fig. 3A). We therefore decided to immunoprecipitate RISC and then determine the RISC-bound small RNA profile by small RNA deep sequencing (RIP-Seq), as previously described (Flores et al. 2013). As predicted, sequencing of RISC-associated small RNAs derived from the parental 293T cells resulted in the selective recovery of small RNAs with the size expected for authentic miRNAs, i.e., 22 ± 2 nt (Fig. 3B), and indeed almost all of these could be aligned to known human miRNAs or miRNA passenger strands (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the small RNA reads recovered after RIP-Seq of RISC-associated small RNAs from the NoDice(4-25) cell line were predominantly <20 nt in length (Fig. 3B) and very few of these reads actually aligned to known human miRNAs (Fig. 3C). Nevertheless, we did detect a very small number of reads in the NoDice(4-25) cell line, ∼1% of the level seen in WT 293T cells, that were ∼22 nt in length and that aligned to known pre-miRNAs. We hypothesize that these RNAs, which were also detected in Figure 2, derive from the high level of pre-miRNAs present in the NoDice cell lines (Fig. 1B) by cleavage of the pre-miRNA terminal loop by a cellular endonuclease followed by loading of one strand of the resultant short RNA duplex into RISC. Alternatively, it is known that Ago2 is able to process pre-miR-451 to yield mature miR-451 (Cheloufi et al. 2010; Cifuentes et al. 2010) and it is possible that Ago2 is also able, at low efficiency, to process other pre-miRNAs. At present, we have no evidence addressing the existence of either of these alternative pre-miRNA processing pathways and, if they indeed occur, they are clearly very inefficient (Figs. 2, 3).

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of small RNA expression in the NoDice cells. (A) Size distribution of small RNAs (16–27 nt) that align to known cellular pri-miRNA hairpins determined by total small RNA deep sequencing of WT 293T cells and the NoDice cells. (B) Similar to A, except that this figure presents data generated using qRT-PCR for a set of seven individual miRNA species that are expressed at readily detectable levels in WT 293T cells.

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of RISC-loaded small RNAs in the NoDice cells. (A) Western analysis of endogenous hDcr and Ago2 expression levels in WT 293T and NoDice(4-25) cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Size distribution of total small RNAs obtained by deep sequencing of RISC-associated small RNAs isolated by immunoprecipitation of Ago2 from 293T or NoDice(4-25) cells. (C) Similar to B except that only the reads that align to known human pri-miRNA hairpins are shown.

Synthetic microRNA duplexes efficiently program RISC in Dicer-deficient cells

Previous work has suggested that Dicer facilitates the loading of mature miRNAs into RISC (Maniataki and Mourelatos 2005; MacRae et al. 2008) but is not essential for this process (Giraldez et al. 2005; Kanellopoulou et al. 2005; Murchison et al. 2005). We tested whether functional RISCs could be generated in the hDcr-deficient NoDice(4-25) cell line by transfection with synthetic miRNA duplex intermediates containing human miR-155, miR-92, or a viral miRNA, miR-K11, derived from KSHV. As we and others have previously reported, the miR-K11 seed sequence (nt 2–8) is identical to that seen in human miR-155, but miR-K11 otherwise differs in primary sequence (Supplemental Fig. S3; Gottwein et al. 2007; Skalsky et al. 2007). As shown in Figure 4, a transfected miR-K11 RNA duplex efficiently inhibited the expression of an RLuc indicator gene bearing two perfect target sites for miR-K11 in its 3′ UTR, and somewhat less effectively inhibited an analogous indicator bearing two perfect miR-155 targets. An RLuc indicator bearing miR-92a target sites was not affected. Conversely, a transfected, synthetic miR-155 RNA duplex strongly inhibited the miR-155 indicator, moderately inhibited the miR-K11 indicator, and again failed to affect the control miR-92a indicator. Finally, the synthetic miR-92a indicator was only repressed by transfection of its cognate RNA duplex (Fig. 4). These data clearly demonstrate that endogenous RISCs present in the NoDice(4-25) cells can be loaded by an introduced miRNA duplex to give a fully functional RISC able to selectively target mRNAs bearing either fully or partially complementary target sites. To examine how efficiently RISC was loaded, we performed RIP-Seq using an anti-Ago2 antibody, as previously described (Flores et al. 2013), and then performed deep sequencing of RISC-associated small RNAs. These data revealed that, in the NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with the miR-K11 RNA duplex, 56.7% of the recovered RISC-associated small RNAs were identical to miR-K11, while a further 0.28% were identical to the miR-K11 passenger strand. Similarly, in the NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with the miR-155 RNA duplex, 10.1% of the RISC-associated small RNAs were miR-155, while a further 1.6% were the miR-155 passenger strand. Therefore, it is possible to efficiently load RISC with a specific miRNA species in these Dicer-deficient human cells, presumably due at least in part to lack of competition from endogenous miRNAs species.

FIGURE 4.

Transfected synthetic miRNA duplexes efficiently program RISC in the NoDice(4-25) cells. NoDice(4-25) cells were cotransfected with an RLuc-based indicator plasmid containing two target sites perfectly (p) complementary to miR-92a, miR-155, or miR-K11 together with a synthetic miRNA duplex encoding one of these three miRNAs. RLuc activity was determined at 24 h post-transfection and was normalized to a control transfection using an irrelevant miRNA duplex as well as to a cotransfected Fluc control.

Because the RISCs present in the Dicer-deficient NoDice(4-25) cells can be efficiently loaded with one specific miRNA species, we reasoned that this should result in the efficient recruitment of RISC to partially complementary endogenous mRNA species. Indeed, analysis of RISC-bound RNA targets in cells transfected with either a synthetic miR-155, miR-K11, or miR-92a miRNA duplex, using the previously described photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation technique (PAR-CLIP) (Hafner et al. 2010; Gottwein et al. 2011), revealed that a remarkable ∼19% of all RISC-binding clusters in the miR-155 transfected NoDice(4-25) cells exhibited ≥6-nt contiguous seed homology to the miR-155 seed sequence. Similarly, ∼13% of the RISC-binding clusters detected using PAR-CLIP in the miR-K11 transfected NoDice(4-25) cells also showed ≥6-nt contiguous seed homology to the miR-K11 seed sequence, which is identical to the miR-155 seed. In contrast, only ∼0.47% of the RISC-binding clusters detected in the miR-92a transfected NoDice(4-25) cells included ≥6-nt contiguous homology to the shared miR-155/miR-K11 seed, which is what would be predicted to occur by chance. Therefore, the NoDice(4-25) cells indeed provide a tool for the efficient recovery of endogenous mRNA target sites for a given miRNA species, although their utility is of course limited by their particular transcriptome.

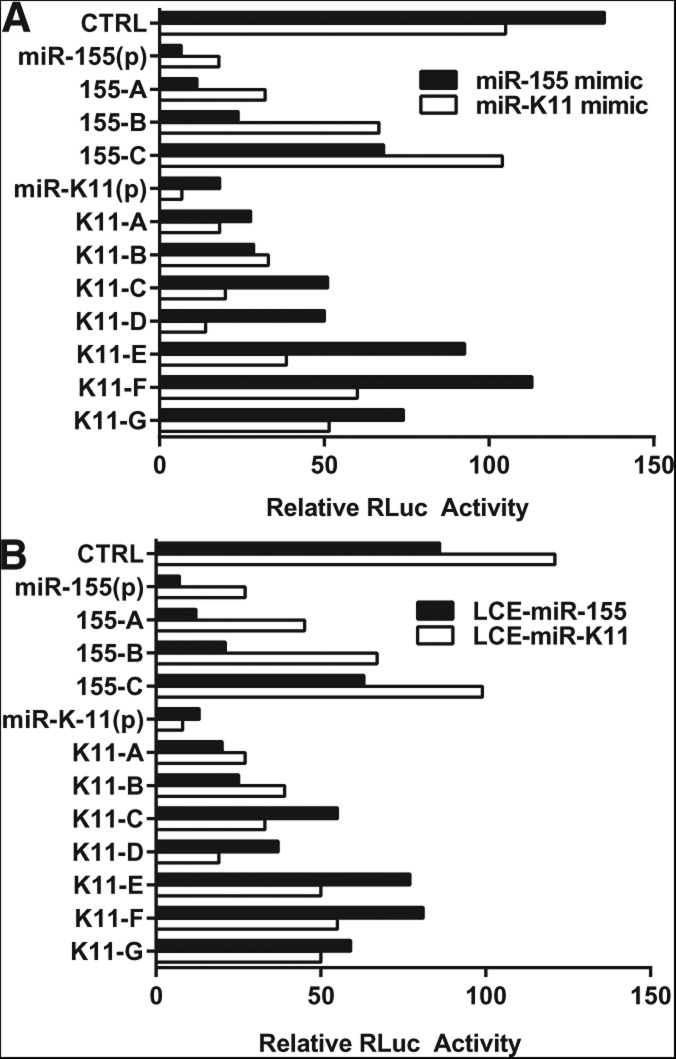

The observation that a high proportion of the RISC-binding clusters detected by PAR-CLIP in NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with either synthetic miRNA duplex miR-155 or miR-K11 showed strong homology to the seed shared by these two miRNAs suggested that this approach might also identify targets for miR-155 and miR-K11 that were not solely seed driven but rather were either noncanonical in nature, i.e., do not have full complementarity to the miRNA seed, or were complementary to the miRNA seed, yet also significantly facilitated by the divergent sequences of miR-155 and miR-K11 located outside the seed. Although numerous mRNA targets shared by miR-155 and miR-K11 have been identified (Gottwein et al. 2007, 2011; Skalsky et al. 2007), and KSHV miR-K11 has been shown to functionally substitute for miR-155 in mediating B-cell function in vivo (Boss et al. 2011; Sin et al. 2013), it has so far remained unclear whether these miRNAs differ in their ability to repress a subset of endogenous mRNA targets. For this purpose, we sought to identify RISC-binding sites, programmed by the synthetic miR-K11 miRNA duplex transfected into NoDice(4-25), that were not detected in the NoDice(4-25) cells programmed using the miR-155 duplex, and vice versa. We therefore used PAR-CLIP to identify intense (>50 reads) RISC-binding clusters present in the miR-155-transfected cells that were lacking (<10 reads) in the miR-K11-transfected NoDice(4-25) cells. This identified 167 miR-155-specific RISC-binding clusters of which 34 (21%) were not seen in the miR-K11 transfected culture. Of these 34, we selected two that showed only partial homology to the shared miR-155/miR-K11 seed, which represent candidate “noncanonical” miRNA targets, and three that not only had seed homology but also significant 3′ complementarity to miR-155, but not to miR-K11, which represent candidate “seed plus” targets (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Similarly, we identified 129 miR-K11-specific RISC-binding sites of which 73 (57%) were not seen in the miR-155 transfected culture. Of these 73, we selected 15 that showed only partial seed homology to miR-K11/miR-155 (noncanonical targets) and four that had not only seed complementarity but also 3′ homology to miR-K11 but not miR-155 (seed-plus targets) (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Two tandem copies of these candidate cellular RNA targets were then introduced into the 3′ UTR of RLuc and tested for function by cotransfection into WT 293T cells along with a synthetic miR-155 or miR-K11 duplex (Fig. 5A) or a pri-miR-155 or pri-miR-K11 expression plasmid (Fig. 5B). Unfortunately, analysis of the 15 candidate noncanonical miR-K11 targets showed that only three of these, termed K11-E, K11-F, and K11-G, were significantly repressed by miR-K11 expression while neither noncanonical miR-155 target showed repression by miR-155 (Fig. 5A,B; data not shown). However, all four tested seed-plus miR-K11 targets, and all three tested seed-plus miR-155, were responsive to their respective miRNA. The sequences of the miRNA-responsive cellular RNA targets, their human genes of origin, and their alignments to miR-K11 and miR-155, are shown in Supplemental Figure S3.

FIGURE 5.

PAR-CLIP of NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with a synthetic miR-155 or miR-K11 miRNA duplex identifies miRNA-specific RNA targets. NoDice(4-25) cells were transfected with a synthetic miR-155 or miR-K11 miRNA duplex and RISC-binding clusters present in one of the transfected cultures, but not in the other or in control NoDice(4-25) cells, identified by PAR-CLIP. We then generated RLuc-based indicator constructs for a number of these potential cellular target sites that displayed both differential RISC binding, as determined by PAR-CLIP, and different degrees of homology to miR-155 and miR-K11, which have an identical 7-nt seed sequence (see Supplemental Fig. S3). These indicators were then cotransfected into WT 293T cells together with the miR-155 or miR-K11 synthetic miRNA mimic (A) or with a pri-miR-155 or pri-miR-K11 expression vector (B). RLuc activity was determined at 24 h post-transfection. These data were normalized to an internal FLuc-based control and are given relative to the level of RLuc activity seen in the absence of an ectopic miRNA.

As shown in Figure 5, all three seed-plus miR-155 targets, designated 155-A, 155-B, and 155-C, were repressed substantially more efficiently by miR-155 than by miR-K11, regardless of whether these miRNAs were expressed from a transfected synthetic miRNA duplex (panel A) or from an endogenously transcribed pri-miRNA (panel B). These targets have either 6-nt (2–7) homology to the miR-155/miR-K11 seed (155-B and 155-C) or full 7-nt homology (155-A) yet were only detected in the miR-155 duplex transfected NoDice(4-25) cells. As shown in Supplemental Figure S3A, these three targets do, however, all share significantly more homology to miR-155 than to miR-K11 outside the seed. Of the four miR-K11 seed-plus targets only two, K11-C and K11-D, shared this pattern of higher responsiveness to the miRNA that induced the observed RISC binding cluster (Fig. 5). The other two tested seed-plus miR-K11 targets, K11-A and K11-B, despite showing substantially more homology to miR-K11 than miR-155 outside the seed region (Supplemental Fig. S3B) and despite the fact that they were only detected by PAR-CLIP in the miR-K11 duplex-transfected NoDice(4-25) cells, nevertheless were equivalently repressed by both miR-K11 and miR-155. We note that both the K11-A and K11-B target share 7-nt seed homology to the miR-K11/miR-155 seed, while both K11-C and K11-D show only 6-nt homology to this seed sequence. Analysis of the three candidate miR-K11 noncanonical targets (designated K11E, K11F, and K11G) indeed showed that all three were more responsive to miR-K11 than to miR-155 (Fig. 5), consistent with the more extensive homology to the former (Supplemental Fig. S3B). However, the repression mediated by these noncanonical miR-K11 targets was quite modest and, as noted above, analysis of 14 other candidate noncanonical targets for miR-K11 or miR-155 failed to detect a significant level of repression. It therefore appears that noncanonical, i.e., non-seed-driven, miRNA target sites are quite rare and that even those that do exist are not able to mediate target mRNA repression very effectively. However, miRNA sequence homology outside the seed can clearly facilitate repression of an mRNA target, especially if the seed homology is only 6 nt rather than the full 7 nt.

Rescue of human microRNA expression by Drosophila Dicer 1

Human somatic cells express a single hDcr protein that functions to process pre-miRNAs into mature miRNAs (Chendrimada et al. 2005). However, full-length mammalian Dicer proteins appear unable to process long dsRNAs into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (Ma et al. 2008; Flemr et al. 2013; Taylor et al. 2013) and infection of mammalian somatic cells with RNA viruses does not result in the detection of significant levels of viral siRNAs (Parameswaran et al. 2010; Cullen et al. 2013). Drosophila, in contrast, encodes two Dicer proteins, dDcr1 and dDcr2. dDcr1 is analogous to hDcr, that is, it functions in pre-miRNA processing but is not effective at processing long dsRNAs into siRNAs (Lee et al. 2004; Förstemann et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2005). In contrast, dDcr2 is able to efficiently process dsRNAs, including viral dsRNAs, into siRNAs but is not effective at generating mature miRNAs from pre-miRNAs (Lee et al. 2004; Miyoshi et al. 2010; Sabin et al. 2013). Importantly, miRNAs generated by dDcr1 cleavage are selectively loaded into Drosophila Ago1, while siRNAs generated by dDcr2 cleavage are selectively loaded into Ago2. This latter process is facilitated by a dsRNA-binding protein called R2D2 (Marques et al. 2010; Okamura et al. 2011; Nishida et al. 2013). In contrast, in mammalian cells, miRNAs generated by hDcr are loaded equivalently well into all four Ago proteins (Wang et al. 2012). Another difference between dDcr1 and dDcr2 is that they require different dsRNA-binding cofactors for dsRNA cleavage. dDcr1 uses the PB isoform of the Drosophila loquacious (Loqs-PB) protein, while dDcr2 requires the PD isoform of Loqs (Loqs-PD) (Hartig et al. 2009). These Drosophila proteins are functionally analogous to the hDcr cofactor TRBP, which is also a dsRNA-binding protein (Benoit et al. 2013).

We were interested in the question of whether either Drosophila Dicer protein, acting either alone or in combination with the relevant Loqs cofactor, would be able to rescue human pre-miRNA processing in the human NoDice cells. We also analyzed whether Drosophila R2D2 could facilitate human miRNA expression. As shown in Figure 6A, we were able to express readily detectable levels of dDcr1, dDcr2, R2D2, Loqs-PD, or Loqs-PB in transfected NoDice(4-25) cells. Analysis of whether any of these proteins could rescue the expression of mature miR-155 in NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with a pri-miR-155 expression plasmid revealed very effective rescue by coexpression of dDcr1 and Loqs-PB but no rescue by dDcr2 together with Loqs-PD and R2D2 (Fig. 6B, lanes 5,7). The dDcr1 protein on its own only very weakly rescued pre-miR-155 processing, while expression of R2D2, as predicted, had no additional positive effect on the rescue of pre-miR-155 processing by dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB (Fig. 6B, lanes 4,6). We next asked whether dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB could also rescue the expression of an endogenous human miRNA, in this case miR-92a, which is the most highly expressed miRNA in wild-type 293T cells. As shown in Figure 6C, coexpression of dDcr1 and Loqs-PB indeed rescued mature miR-92a expression, albeit not quite as effectively as ectopic hDcr expression, and this rescue was again not further enhanced by coexpression of the Drosophila R2D2 protein.

FIGURE 6.

Drosophila Dicer 1 and loquacious PB rescue pre-miRNA processing in NoDice(4-25) cells. (A) Western analysis of NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with vectors encoding His-tagged dDcr1 or dDcr2 or Flag-tagged R2D2, Loqs-PD, or Loqs-PB. Although dDcr1 and dDcr2 are similar in molecular mass, it has previously been observed that dDcr2 migrates more rapidly upon gel electrophoresis (Miyoshi et al. 2010). (B) Northern analysis of pre-miR-155 and mature miR-155 expression in NoDice(4-25) cells cotransfected with a pri-miR-155 expression vector and the indicated Dicer or Dicer cofactor expression vectors. (C) An analysis of the level of endogenous, mature miR-92a-3p expression detected in the NoDice(4-25) cells, or NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with the indicated expression vectors, as determined by qRT-PCR. These data were normalized to the parental 293T cell line, which was set at 100%, and are similar to what was observed by deep sequencing (Fig. 7B).

To obtain a more complete overview of the human miRNAs expressed in NoDice(4-25) cells expressing either ectopic hDcr or dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB, we next performed deep sequencing of the small RNA species expressed in these cells 72 h after transfection with the relevant expression plasmids. As shown in Figure 7A, expression of either hDcr or dDcr1/Loqs-PB largely rescued the expression of the expected population of small RNAs 22 ± 2 nt in length, giving rise to a small RNA size profile very similar to that seen in the WT 293T cells. Analysis of the expression level of individual human miRNAs, focusing on the 10 miRNAs recovered at the highest frequency by deep sequencing of small RNAs in WT 293T cells, showed that both hDcr and the combination of dDcr1/Loqs-PB gave rise to similar levels of these individual mature human miRNAs. Interestingly, however, the similar pattern of mature miRNA expression observed in the NoDice(4-25) cells expressing either ectopic hDcr or dDcr1/Loqs-PB differed significantly from the pattern seen in the WT 293T cells. In particular, both the hDcr and the dDcr1/Loqs-PB gave rise to NoDice(4-25) cells expressed levels of miR-10a-5p and miR-16-5p that, as a percentage of the total mature miRNA population, were substantially higher than seen in WT 293T. Conversely, the relative level of some other mature miRNAs, e.g., miR-103a-3p or miR-486-5p, was substantially lower in both the hDcr and dDcr1/Loqs-PB expressing NoDice(4-25) cells than in WT 293T (Fig. 7B). While it is possible that these differences result from different levels of processing efficiency for specific pre-miRNAs under conditions where Dicer levels are limiting, it is also possible that the level of expression of specific pre-miRNAs in the NoDice(4-25) cells differs substantially from that seen in WT 293T cells due to dysregulation of gene transcription in these miRNA-deficient cells.

FIGURE 7.

Rescue of endogenous miRNA expression in NoDice(4-25) cells by expression of dDcr1 and its cofactor Loqs-PB. (A) Size distribution of small RNA species that align to human pri-miRNA hairpins in WT 293T cells, the parental NoDice(4-25) cells, and in NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with plasmids encoding full-length hDcr or expressing dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB, as determined by deep sequencing at 72 h post-transfection. (B) Relative expression of the 10 most highly expressed endogenous mature miRNA species in WT 293T cells, the parental NoDice(4-25) cells, or NoDice(4-25) cells expressing ectopic hDcr or dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB. These data were derived by deep sequencing of total small RNAs at 72 h post-transfection.

The TRBP cofactor required by hDcr has been proposed to influence the cleavage site on pre-miRNAs that is utilized by hDcr (Lee and Doudna 2012; Lee et al. 2013) and the Loqs-PB protein has also been proposed to influence pre-miRNA cleavage site selection by dDcr1 (Fukunaga et al. 2012), resulting in the potential formation of alternative isomiRs. Moreover, the hDcr/TRBP complex has also been proposed to play a role in RISC loading (Chendrimada et al. 2005; MacRae et al. 2008). We therefore wondered whether expression of the dDcr1/Loqs-PB complex in the NoDice(4-25) cells might result in a change in the relative expression level of different human isomiRs and/or affect the efficiency of loading of the miRNA strand into RISC, relative to the miRNA passenger strand.

Mature miRNAs can derive from either the 5′ arm of the pre-miRNA stem, in which case they are referred to as 5p miRNAs, or from the 3′ arm, in which case they are referred to as 3p miRNAs. For 5p miRNAs, the 5′ end is determined by Drosha cleavage, while the identity of the 3′ end is controlled by Dicer. Conversely, in the case of 3p miRNAs, the 5′ end is determined by Dicer, while the 3′ end is cleaved by Drosha. Because the 5′ proximal miRNA seed sequence is, as discussed above, a critical determinant of mRNA target selection, we focused our analysis on the identity of the 5′ end of 3p miRNAs expressed in NoDice(4-25) cells. More particularly, we focused on 3p miRNAs that gave rise to a significant level (>0.1% of the reads for that miRNA) of isomiRs that are either longer than the dominant miRNA species at the 5′ end (Table 1A) or shorter at the 5′ end than the dominant miRNA species (Table 1B). MiRNAs that showed a greater than twofold difference in the relative expression of isomiRs in the hDcr vs. dDcr1/Loq-PB expressing NoDice(4-25) cells are listed in Table 1. Interestingly, we observed for two miR-30 family miRNAs that the dominant isomiR in the hDcr-expressing cells became a minor species in the dDcr1/Loqs-PB expressing cells. Thus, the shorter isoforms of miR-30a-3p and miR-30d-3p contributed 72% and 58%, respectively, of the total populations of these related miRNAs in NoDice cells(4-25) cells expressing ectopic hDcr, yet this fell to 7.9% and 7.8%, respectively, in the NoDice(4-25) cells expressing dDcr1/Loqs-PB (Table 1B). The fact that the closely related miR-30a-3p and miR-30d-3p, as well as miR-30e-3p, where the shorter isoform dropped from 35% of the total in the hDcr cells to 1.2% in the dDcr1/Loqs-PB cells, and the more divergent miR-30c-3p, where the shorter isoform declined by a remarkable 42-fold in the dDcr1/Loqs-PB expressing NoDice(4-25) cells, all behaved similarly argues that hDcr/TRBP and dDcr1/Loqs-PB are consistently cleaving these related pre-miR-30 precursors at sites differing by 1 nt, resulting in a drop of from ∼42-fold to approximately sevenfold in the relative expression of the shorter isoform of the 3p strand of these four human miRNAs in cells expressing dDcr1/Loqs-PB relative to the hDcr-expressing NoDice(4-25) cells (Table 1B). Significant differences were also observed for other endogenous miRNAs, with the longer isoforms of miR-29a-3p, miR-671-3p, and miR-151a-3p increasing by approximately eightfold, ∼12-fold, and ∼13-fold, respectively, in the dDcr1/Loqs-PB-expressing cells relative to the hDcr-expressing cells (Table 1A), while the expression of the shorter isoform of miR-22-3p decreased by ∼18-fold in the NoDice(4-25) cells expressing dDcr1/Loqs-PB. Conversely, in the case of miR-92b-3p, the expression of the shorter isoform increased by ∼78-fold in the dDcr1/Loqs-PB cells relative to the cells expressing hDcr. However, even when the relative expression of isomiRs differing at their 5′ end changed by several fold, this in general did not affect the identity of the dominant isoform (with the exception of miR-29a-3p, miR-30a-3p, and miR-30d-3p, as noted above) and we therefore would not expect a substantial effect on the function of most mature miRNA species.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of isomiR expression in NoDice(4-25) cells expressing ectopic hDcr or dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB

We next asked whether the ectopic expression of hDcr vs. dDcr1/Loqs-PB might affect the relative loading of the miRNA vs. passenger strand into RISC. In Table 2, we present a list of human miRNAs that were recovered >5000 times in the deep-sequencing library where the miRNA passenger strand represents >1% of these reads and where the relative recovery of the passenger strand differed by more than twofold. The most extreme example observed was for miR-30c, where the 5p arm was dominant in the presence of hDcr, yet the 3p arm became dominant in the presence of dDcr1/Loq-PB. Similarly, for the related miR-30e, the 5p arm again predominated in the presence of hDcr, while the 3p arm became the dominant arm in cells expressing dDcr1/Loqs-PB (Table 2). We note, as shown in Table 1, that several miR-30 family members were also expressed at different isoform ratios in the presence of hDcr vs. dDcr1/Loqs-PB. As the identity of the 5′ terminal nucleotides of the miRNA and passenger strands that form the miRNA duplex intermediate are known to influence which strand is loaded into RISC (Khvorova et al. 2003), we hypothesize that this change in miRNA isoform ratio is partly responsible for the observed effects on miRNA recovery. However, as we did not observe significant changes in isomiR expression for all the miRNAs listed in Table 2, this cannot be the complete explanation for the observed changes in the detection of the miRNA strand vs. the passenger strand in NoDice(4-25) cells in the presence of hDcr vs. dDcr1/Loqs-PB. Although readily detectable, the observed changes in strand recovery generally did not change the identity of the dominant, miRNA strand (with the exception of some miR-30 family members as well as miR-151a) and we therefore do not expect that these changes, while interesting, would have any major consequences for miRNA function.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of the relative loading of the miRNA and passenger strands onto RISC for selected endogenous miRNA species

DISCUSSION

Previously, several laboratories have described the derivation and characterization of murine ES cells (Murchison et al. 2005; Calabrese et al. 2007; Chong et al. 2010) and MEFs (Frohn et al. 2012; Smibert et al. 2013) that do not express a functional Dicer protein. As expected, these cells were reported to lack the ability to express mature miRNA species and, in the case of ES cells, it has also been reported that they had lost the ability to undergo differentiation (Bernstein et al. 2003; Kanellopoulou et al. 2005). Perhaps because of the difficulty of growing and manipulating ES cells and primary MEFs in culture, little else has been reported about these Dicer-deficient cells, although it has been demonstrated that the RISCs present in Dicer-deficient ES cells can be programmed by transfection of synthetic miRNA duplexes (Kanellopoulou et al. 2005; Murchison et al. 2005).

In this study, we describe the derivation of the first human, and first transformed Dicer-deficient cell line. These cells were generated by TALEN-mediated genome editing in 293T cells, a cell line that is simple to culture and transfect and, hence, widely used in biological research. As previously noted for Dicer-negative murine ES cells (Calabrese et al. 2007; Chong et al. 2010), the resultant “NoDice” cell lines express very low levels of mature miRNAs, generally >100-fold less than seen in the parental 293T cells, although a very low level of mature miRNA expression does remain detectable, as measured by both RT-PCR (Fig. 2B) and deep sequencing of RISC-associated small RNAs (Fig. 3). However, these levels appear insufficient to mediate a detectable level of repression of miRNA indicator plasmids (Fig. 1C). Nevertheless, and as previously reported for Dicer-deficient ES cells (Kanellopoulou et al. 2005; Murchison et al. 2005), the RISCs present in the NoDice(4-25) cell line can be efficiently programmed by introduction of exogenous, synthetic miRNA duplexes, with up to 50% of all RISC-associated small RNAs originating from the transfected duplex RNA. We hypothesized that the highly efficient loading of RISC in the NoDice(4-25) cells by a single mature miRNA species, with the attendant reduction in “background” RISC-binding sites, might facilitate the detection of minor, potentially noncanonical RISC-binding sites programmed by that miRNA. We therefore asked whether the NoDice(4-25) cells could be used to identify target sites specific for two miRNAs, cellular miR-155 and KSHV miR-K11, that share an identical seed but are otherwise different in primary sequence (Supplemental Fig. S3; Gottwein et al. 2007; Skalsky et al. 2007). KSHV miR-K11 has been previously shown to target many of the same mRNAs as miR-155 (Gottwein et al. 2007; Skalsky et al. 2007) and miR-K11 has even been shown to rescue B-cell development in miR-155-deficient mice (Boss et al. 2011; Sin et al. 2013). Nevertheless, it has seemed possible that miR-K11, which is highly conserved during KSHV evolution (Marshall et al. 2007), might also selectively target specific host mRNAs to give an additional selective advantage to this virus, when compared with simply activating the expression of endogenous miR-155, the strategy followed by the related human γ-herpesvirus Epstein-Barr virus (Linnstaedt et al. 2010).

Using the PAR-CLIP technology (Hafner et al. 2010), we were indeed able to identify mRNA target sites for RISCs programmed by a miR-K11 RNA duplex that were not detected in NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with a miR-155 duplex, and vice versa. A number of these represented sites that displayed 6- or even 7-nt seed homology to both miR-155 and miR-K11, yet also featured more extensive homology to either miR-155 or miR-K11 (Supplemental Fig. S3). Functional analysis (Fig. 5) of seven of these “seed plus” targets indeed revealed that five of these (three miR-155 targets and two miR-K11 targets) showed significantly more repression by the cognate miRNA than by the less complementary, seed identical miRNA species. However, two candidate “seed plus” miR-K11 targets showed equivalent repression by both miR-K11 and miR-155 (Fig. 5), raising the question of why these binding sites were only detected by PAR-CLIP in cells expressing miR-K11. We note that these latter two RNA targets in fact showed full, 7-nt seed homology to both miR-K11 and miR-155, while four of the five targets that showed specificity were only 6-nt seed targets. It is therefore possible that miRNA sequence homology outside the seed region is particularly important in the case of mRNA targets showing only partial seed homology.

Functional analysis of 17 candidate “noncanonical” targets for miR-155 or miR-K11, i.e., targets lacking full homology to nucleotide positions 2–7 of the miRNA, proved largely disappointing as only three of the 17 tested targets, all for miR-K11 (Supplemental Fig. S3B), showed a detectable level of repression by miR-K11. Importantly, however, these targets were poorly responsive to miR-155 and to our knowledge this therefore represents the first report of functional, noncanonical targets that discriminate between two miRNAs that have identical seeds. Whether this observation indeed implies the existence of phenotypically important mRNA targets that are specific for miR-K11 but not miR-155, or vice versa, will require additional experimental analysis.

The ease of manipulation of the NoDice(4-25) cell line has also allowed us to ask whether pre-miRNA processing might be rescued by ectopic expression of heterologous Dicer proteins. In particular, we examined whether dDcr1, which is responsible for pre-miRNA processing in Drosophila (Lee et al. 2004; Förstemann et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2005), would be able to rescue miRNA processing in the NoDice(4-25) cells. As shown in Figure 6B, this was indeed found to be the case, although rescue of pre-miRNA processing by dDcr1 was only efficient upon coexpression of Loqs-PB, the Drosophila homolog of TRBP (Hartig et al. 2009; Benoit et al. 2013). This likely results from the inability of human TRBP to bind to dDcr1 in coexpressing cells and, hence, form a functional pre-miRNA processing complex with dDcr1 (data not shown). As expected, dDcr2, which normally functions in siRNA biogenesis in Drosophila (Lee et al. 2004; Sabin et al. 2013), was in contrast unable to rescue mature miRNA production in the NoDice(4-15) cell line, even in the presence of its cofactors Loqs-PD and R2D2 (Fig. 6B; Hartig et al. 2009; Marques et al. 2010). Whether dDcr2 can confer on the NoDice(4-25) cells the ability to generate siRNAs is currently under investigation.

A more detailed analysis of the mature miRNAs produced in the NoDice(4-25) cell line upon ectopic expression of hDcr or dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB (Fig. 7) revealed a number of minor but interesting differences (Tables 1, 2). For example, in the case of a subset of human pre-miRNAs, ectopic hDcr and dDcr1/Loqs-PB gave rise to significantly different ratios of several 3p isomiRs that differ by 1 or 2 nt at their 5′ end (Table 1). In particular, for miR-30 seed family members, expression of hDcr increased the relative production of the shorter 5′ isoform by up to 42-fold when compared with ectopic dDcr/Loqs-PB expression (Table 1B). These data are consistent with previous reports suggesting that the selection of Dicer cleavage sites on pre-miRNAs is influenced by the hDcr and dDcr1 cofactors TRBP and Loqs-PB, respectively (Fukunaga et al. 2012; Lee and Doudna 2012; Lee et al. 2013). These findings also imply that pre-miRNA cleavage by dDcr1 does not require any cofactors other than Loqs-PB.

Analysis of whether the ectopic expression of hDcr vs. dDcr1/Loqs-PB would affect the efficiency of miRNA vs. passenger strand loading into RISC also revealed a number of clear differences. Some of the most dramatic effects were again observed with miR-30 seed family members, with miR-30e and miR-30c, for example, switching from predominantly 5p recovery in the presence of hDcr to predominantly 3p recovery in the presence of dDcr1/Loqs-PB (Table 2). We hypothesize that this effect is, at least in part, due to changes in the relative levels of the longer and shorter isoforms of miR-30 seed family members, as documented in Table 1B, as the identity of the termini of miRNAs is known to influence the relative RISC loading of the two strands present in the miRNA duplex intermediate (Khvorova et al. 2003). However, we also noted significant changes in the relative recovery of other miRNA/passenger strand pairs that did not show significant changes in isomiR production suggesting, as indeed previously argued, that the hDcr/TRBP heterodimer might play a role in RISC loading, though this role is clearly not an essential one (Maniataki and Mourelatos 2005; MacRae et al. 2008).

In conclusion, we have generated and functionally analyzed the first human Dicer-deficient cell line. As expected, these cells lack significant levels of endogenous miRNA expression (Figs. 2, 3), though they can be efficiently programmed using exogenous synthetic miRNA duplexes. This property is potentially useful in defining miRNA targets sites, using techniques such as PAR-CLIP (Hafner et al. 2010), as the background of target sites for other miRNAs is much reduced, and we demonstrate that this cell line can indeed be used to identify functional, noncanonical target sites for a viral miRNA, miR-K11 (Fig. 5). We also demonstrate that these cells can be used to examine the ability of heterologous Dicer proteins to rescue mature miRNA biogenesis and we show that ectopic expression of dDcr1, in combination with its cofactor Loqs-PB, is indeed able to effectively rescue human miRNA production (Fig. 6), albeit with minor, potentially significant differences in the relative production of different isomiRs and in miRNA vs. passenger strand loading into RISC (Tables 1, 2). It will also be of interest to test whether amino-terminally truncated forms of hDcr, analogous to those recently reported to be expressed in murine germ cells (Flemr et al. 2013), are capable of not only rescuing pre-miRNA processing in the NoDice(4-25) cells but also of allowing the production of viral siRNAs in these human somatic cells, as has recently been reported in virally infected murine ES cells (Maillard et al. 2013).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular clones

The miR-155 expression plasmid, pLCE-miR-155, has been previously described (Gottwein et al. 2007). The miR-K11 expression plasmid, pLCE-miR-K11, was generated by PCR amplification of a DNA segment from the previously described plasmid pNL-SIN-CMV-AcGFP- miR-K11 (Gottwein et al. 2007) using oligonucleotides containing SalI and MfeI restriction sites. This PCR product was digested and ligated into pLCE linearized with XhoI and EcoRI. All miRNA indicator constructs were constructed using the parental psiCHECK-2 (Promega) plasmid, which contains both rluc and fluc. Oligonucleotides encoding two perfect miRNA targets, separated by a short spacer, were designed to leave NotI and XhoI compatible ends when annealed. The duplexes were ligated into psiCHECK-2 linearized with XhoI and NotI to generate indicator plasmids containing perfect target sites specific for miR-155, miR-K11, or miR-92a (psi-miR-155(p), psi-miR-K11(p), and psi-miR-92a(p)). This approach was also used to generate miRNA indicator constructs that contain imperfect miRNA target sites, containing bulges at positions 10 and 11, for miR-155 and miR-92a (psi-miR-155(b) and psi-miR-92a(b), respectively).

Reporters for miR-K11 and miR-155 targets identified by PAR-CLIP were constructed as follows: Complementary oligonucleotides containing two identical PAR-CLIP miR-K11 or miR-155 library-specific miRNA-binding sites, separated by a short spacer, were annealed and ligated into psiCHECK2 to construct psi-155-A, psi-155-B, psi-155-C and psi-K11-A, psi-K11-B, psi-K11-C, psi-K11-D, psi-K11-E, psi-K11-F, and psi-K11-G (Supplemental Fig. S3).

The hDcr expression plasmid pkH3-Dcr-T7, has been previously described (Yi et al. 2005). The cDNAs for dDcr1and dDcr2 were a gift from Dr. Qinghua Liu (Ye and Liu 2008). The ORFs, including in-frame His epitope tags, were moved into pcDNA3 to generate pcDNA-His-dDcr1 and pcDNA-His-dDcr2. The cDNAs for the Drosophila Dicer cofactors Loqs-PB, Loqs-PD, and R2D2 were kindly provided by Dr. Klaus Foerstemann (Hartig et al. 2009). The ORFs were PCR amplified using gene-specific primers designed to include sequences encoding an in-frame N-terminal FLAG epitope tag and then cloned into pcDNA3 to generate pcDNA-FLAG-Loqs-PB, pcDNA-FLAG-Loqs-PD, and pcDNA-FLAG-R2D2.

Cell culture

293T and the NoDice(2-20) and NoDice(4-25) derivatives were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini) and Gentamicin (GIBCO).

Western blot

Expression of dDcr1 and dDcr2 was verified by Western blot using a mouse monoclonal α-His antibody (GE Healthcare Life Sciences #27-4710-01). Expression of Dicer cofactor FLAG-tagged constructs was verified using mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 (F3165/Sigma-Aldrich). After washing, the blots were incubated with anti-mouse IgG-HRP (A9044, Sigma-Aldrich), washed again, and then incubated with the WesternBright Sirius Western blotting detection kit (K-12043-D20/Advansta). Chemiluminesence was visualized using the G:Box Imaging System and GeneSys software (Syngene).

TALEN design

A pair of gene-specific TALENs were designed using the ZiFit Targeter program (http://zifit.partners.org) to target the hdcr gene and cleave at nucleotide 1095 of the hDcr ORF (TALEN recognition sequences are underlined with the cleavage site in bold in the unique sequence tgtgaagagcacttctccaccTgcctcacttgacctgaaatttgtaactccta found within the hDcr ORF). TALENs were constructed using the REAL Assembly TALEN kit (Sander et al. 2011) (Addgene). The TALENs were FLAG epitope tagged and their expression validated by transfection into 293T cells followed by Western blot using a FLAG-specific monoclonal antibody, as described above. TALEN function was tested by generation of a vector containing the entire hDcr target site listed above inserted between a translation initiation codon and a 3′ gfp indicator gene. TALEN function was detected by the specific loss of GFP expression, as determined by FACS, after cotransfection of the TALEN pair with the gfp-based indicator into 293T cells.

Generation and characterization of NoDice cell lines

3 × 105 293T cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate method with 2 µg of each TALEN expression plasmid. After two sequential transfections with the hDcr-specific TALEN expression plasmids, individual clones were isolated by serial dilution and assayed by Western Blot for loss of hDcr expression using an antibody that recognizes amino acids 1701–1912 of hDcr (H-212/Santa Cruz). Total cell lysates were transferred to nitrocellulose and following incubation with the primary anti-hDcr antibody, the blot was probed with a secondary α-Rabbit-HRP antibody (A6154/ Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed as described above. Genomic DNA was isolated (DNeasy/Qiagen) from the parental 293T line and the two NoDice cell lines (2–20 and 4–25). The TALEN-targeted region of hDcr was amplified by PCR and cloned into pcDNA3. Multiple individual clones were sequenced from the parental 293T and NoDice cell lines and three distinct hdcr gene deletions identified in each NoDice cell line.

Transfection of pri-miR-155 expression plasmids and Northern blots

MiRNA expression in NoDice cells was analyzed by Northern blot, as previously described (Bogerd et al. 2010). All transfections were performed using Fugene6 (Promega) and the supplier's protocol. 2 × 106 293T, NoDice(2-20), or NoDice(4-25) cells were transfected with 10 μg of the pLCE-155 miRNA expression plasmid and 5 µg pcDNA3-hDcr or pcDNA3 for the human Dicer complementation experiment. NoDice cells assayed for exogenous miRNA expression rescue by Drosophila Dicer proteins were transfected with pLCE-miR155 (10 µg), hDcr1, dDcr1, or dDcr2 (5 µg) and the Drosophila Dicer cofactors pcDNA-FLAG-Loqs-PB, pcDNA-FLAG-Loqs-PD, pcDNA-FLAG-R2D2, or pcDNA (2.5 µg each as needed) for a total of 20 µg plasmid DNA. NoDice(4-25) cells used for Drosophila Dicer rescue of endogenous human miRNA expression were transfected with hDcr1 or dDcr1 (5 µg) and the Drosophila Dicer cofactors pcDNA-FLAG-Loqs-PB, pcDNA-FLAG-R2D2, or pcDNA (2.5 µg each as needed) for a total of 10 µg. Total RNA was isolated from transfected 293T or NoDice cells (Trizol, Ambion) and 25 μg RNA fractionated on a 15% TBE-Urea gel (Bio-Rad). RNA was transferred to HyBond-N membrane (Amersham) and UV-crosslinked (Stratalinker, Stratagene). Membranes were pre-hybridized in ExpressHyb (Clontech) and then incubated at 37°C with a 32P end-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to miR-155 (5′-ACCCCTATCACGATTAGCATTAA-3′). Membranes were washed with 2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 37°C and miRNA expression visualized by autoradiography.

Transfection of NoDice(4-25) cells with miR-K11, miR-155, and miR-92a miRNA duplexes

RNA oligonucleotides for miR-155 (5′-UUAAUGCUAAUCGUGAUAGGGGU-3′) and miR-155 passenger (5′-CUCCUAUCAUAUUAGCAUUAACA-3′), miR-K11 (5′-UUAAUGCUUAGCCUGUGUCCGA-3′) and miR-K11 passenger (5′-GGGCACAGCUUAAACAUUGAGG-3′), and miR-92a (5′-UAUUGCACUUGUCCCGGCCUGU-3′) and miR-92a passenger (5′-AGGUUGGGAUCGGUUGCAAUGCU-3′) were annealed to form RNA duplex miR-155, miR-K11, and miR-92a mimics, as previously described (Flores et al. 2013). Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 together with 50 ng of a psiCHECK2-based miR-155, miR-K11, or miR-92a-based indicator plasmid and 40 picomoles annealed miRNA mimic. Luciferase activity was assayed at 24 h and analyzed as described below.

Analysis of miRNA indicator plasmids in NoDice cells

A total of 50 ng of the psiCHECK2-miR-155 bulged reporter, 50 ng of pLCE-miR-155 miRNA expression vector, and 400 ng of pGEM3Zf(+) (Promega) as carrier were transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI) into 105 293T cells or NoDice cells plated the previous day. Cells were lysed 24 h later and assayed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega). The ratios of RLuc to FLuc function were calculated and normalized to the ratio of the reporter cotransfected with the parental pLCE vector lacking any miRNA sequence.

Deep sequencing of small RNAs

Total small RNA was isolated from the parental NoDice(4-25) cells, or from NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with hDcr or dDcr1 plus Loqs-PB, using Trizol and RNAs ∼15–30 nt in length fractionated by PAGE on 15% TBE-Urea gels (Bio-Rad). Small RNA was electroeluted from the excised gel slice (Gel Eluter/Hoefer), and cloned as previously described (Whisnant et al. 2013). Adapter-ligated small RNAs were reverse transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), amplified using GoTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Promega) with the Tru-Seq 3′ indices (Illumina), and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000.

RIP-Seq of RISC-associated small RNAs

RISC-bound RNAs from the parental 293T, NoDice(4-25) cells, or NoDice(4-25) cells or cells transfected with the miRNA mimics for miR-155, miR-K-11, or miR-92a, were isolated by immunoprecipitation using an Ago2-specific monoclonal antibody (AB57113, Abcam), as previously described (Flores et al. 2013). Proteins were removed by digestion with Proteinase K and small RNAs recovered using the miRVana kit (Ambion). The RIP-Seq cDNA library was constructed as previously described using the TruSeq small RNA cloning kit (Illumina) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000.

Analysis of deep sequencing/RIP-Seq

Initial reads were quality filtered with cassava 1.8.2. Adapter sequences were clipped and reads ≥15 nt in length quality filtered using the FASTX-toolkit v0.0.13 (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html). Bowtie v.0.12.7 (Langmead et al. 2009) was used to sequentially filter and assign reads to adapter sequences, miRBase v.20 miRNA hairpins (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones 2011), and the human genome assembly 19. miRNA reads were determined from alignments to miRBase entries with no mismatches, while two mismatches were allowed for alignments to the human genome. Reads aligning to multiple locations in a database were distributed equally between each location.

PAR-CLIP of NoDice(4-25) cells

NoDice(4-25) cells, transfected with annealed duplex miR-155, miR-K11, or miR-92a mimics using RNAiMax (Invitrogen) following the supplier's protocol, were subjected to PAR-CLIP as previously described (Hafner et al. 2010). Briefly, 48 h post-transfection, cells were labeled with 100 µM 4-thiouridine (T4509, Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h. Cells were washed with PBS and cross-linked with a Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene) at 365 nm and processed as previously described. RISC cross-linked RNAs were isolated using α-AGO2 antibody (AB57113, Abcam) and small RNAs were cloned using the TruSeq small RNA cloning kit (Illumina). PAR-CLIP was also performed on parental 293T and nontransfected NoDice (4-25) cells.

PAR-CLIP data were analyzed as described previously (Flores et al. 2013). Briefly, Illumina Hi-Seq reads were adapter trimmed, quality filtered, and collapsed with the fastx-tookit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html). These reads were then aligned to the human genome build hg19 with Bowtie 1, and analyzed using PARalyzer v1.1 (Corcoran et al. 2011). Overlapping background clusters, with a minimum read depth of 5, identified in the nontransfected NoDice(4-25) cell line, or NoDice(4-25) cells transfected with the miR-92a duplex described above, were then subtracted from the ≥50 read depth cluster sets obtained from the miR-155 and miR-K11 transfected NoDice(4-25) cells. Then, both of these high-stringency data sets were used to subtract the overlap of the miR-K11 (miR-155 set) or miR-155 (miR-K11 set) to obtain RISC-binding clusters specific for each set. Specifically, the miR-K11 or miR-155 ≥10 read depth cluster set was subtracted from the high-stringency ≥50 read depth sets described above. These unique, high-stringency binding clusters were then used as input for a custom Perl script designed to scan for miR-155 or miR-K11 targets using the miRanda program (Enright et al. 2003). Finally, the set of high miRanda score cutoff targets was used to construct indicator plasmids to test for responsiveness to miR-155 and miR-K11.

IsomiRs were analyzed with a custom Perl script that takes reads entirely complementary to the miRNA hairpin in question, assigns a mature miRNA species rigorously for unambiguous reads, and finally enumerates the length and terminus of the isomiR species in question. This script is available upon request.

qRT-PCR of endogenous microRNAs in NoDice(4-25) cells

Total RNA was analyzed for endogenous cellular miRNA expression as previously described (Flores et al. 2013). Ten nanograms of total RNA was analyzed using TaqMan miRNA assays (Invitrogen) for the following mature human miRNAs: miR-16 (assay #391), miR-21 (#397), miR-22 (#398), miR-25 (#403), miR-92a (#431), miR-101 (#2253), and miR-138 (#2284). Relative expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001) with U6 snRNA (#1973) as the reference. Control reactions lacking either reverse transcriptase or RT primers were performed to verify clean backgrounds in all samples.

Rescue of endogenous microRNA expression in NoDice(4-25) cells expressing ectopic hDcr or dDcr1

Ten nanograms of total RNA from NoDice cells (4-25) expressing hDcr, dDcr1, and Loqs-PB or dDcr1, Loqs-PB, and R2D2 was analyzed for miR-92a expression by RT-PCR as described above. Small RNA species were isolated using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). A total of 300 ng of size-fractionated small RNAs were then sequenced with the TruSeq small RNA cloning kit (Illumina) as described above.

DATA DEPOSITION

Sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (GEO accession number GSE56836). Processed files will be made available on request.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded in part by NIH grants R01-AI0967868 and R01-DA0300086 to B.R.C. A.W.W. and O.F. were supported by T32-CA009111, while E.M.K. was supported by T32-AI007392. We thank Scott Hammond, Qinghua Liu, and Klaus Förstemann for clones used in this research.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.044545.114.

REFERENCES

- Benoit MP, Imbert L, Palencia A, Perard J, Ebel C, Boisbouvier J, Plevin MJ 2013. The RNA-binding region of human TRBP interacts with microRNA precursors through two independent domains. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 4241–4252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Chung WJ, Willis J, Cuppen E, Lai EC 2007. Mammalian mirtron genes. Mol Cell 28: 328–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ 2003. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet 35: 215–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd HP, Karnowski HW, Cai X, Shin J, Pohlers M, Cullen BR 2010. A mammalian herpesvirus uses noncanonical expression and processing mechanisms to generate viral microRNAs. Mol Cell 37: 135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss IW, Nadeau PE, Abbott JR, Yang Y, Mergia A, Renne R 2011. A Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded ortholog of microRNA miR-155 induces human splenic B-cell expansion in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rγnull mice. J Virol 85: 9877–9886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM 2005. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol 3: e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JM, Seila AC, Yeo GW, Sharp PA 2007. RNA sequence analysis defines Dicer's role in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 18097–18102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla D, Xie M, Steitz JA 2011. A primate herpesvirus uses the integrator complex to generate viral microRNAs. Mol Cell 43: 982–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, Hannon GJ 2010. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature 465: 584–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R 2005. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 436: 740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MM, Zhang G, Cheloufi S, Neubert TA, Hannon GJ, Littman DR 2010. Canonical and alternate functions of the microRNA biogenesis machinery. Genes Dev 24: 1951–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF 2010. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics 186: 757–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes D, Xue H, Taylor DW, Patnode H, Mishima Y, Cheloufi S, Ma E, Mane S, Hannon GJ, Lawson ND, et al. 2010. A novel miRNA processing pathway independent of Dicer requires Argonaute2 catalytic activity. Science 328: 1694–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran DL, Georgiev S, Mukherjee N, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Keene JD, Ohler U 2011. PARalyzer: definition of RNA binding sites from PAR-CLIP short-read sequence data. Genome Biol 12: R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR 2004. Transcription and processing of human microRNA precursors. Mol Cell 16: 861–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR, Cherry S, tenOever BR 2013. Is RNA interference a physiologically relevant innate antiviral immune response in mammals? Cell Host Microbe 14: 374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ 2004. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 432: 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS 2003. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol 5: R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemr M, Malik R, Franke V, Nejepinska J, Sedlacek R, Vlahovicek K, Svoboda P 2013. A retrotransposon-driven dicer isoform directs endogenous small interfering RNA production in mouse oocytes. Cell 155: 807–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores O, Nakayama S, Whisnant AW, Javanbakht H, Cullen BR, Bloom DC 2013. Mutational inactivation of herpes simplex virus 1 microRNAs identifies viral mRNA targets and reveals phenotypic effects in culture. J Virol 87: 6589–6603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förstemann K, Tomari Y, Du T, Vagin VV, Denli AM, Bratu DP, Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf WE, Zamore PD 2005. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol 3: e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohn A, Eberl HC, Stohr J, Glasmacher E, Rudel S, Heissmeyer V, Mann M, Meister G 2012. Dicer-dependent and -independent Argonaute2 protein interaction networks in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: 1442–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Han BW, Hung JH, Xu J, Weng Z, Zamore PD 2012. Dicer partner proteins tune the length of mature miRNAs in flies and mammals. Cell 151: 533–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF 2005. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science 308: 833–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Mukherjee N, Sachse C, Frenzel C, Majoros WH, Chi J-tA, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Ohler U, et al. 2007. A viral microRNA functions as an ortholog of cellular miR-155. Nature 450: 1096–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Corcoran DL, Mukherjee N, Skalsky RL, Hafner M, Nusbaum JD, Shamulailatpam P, Love CL, Dave SS, Tuschl T, et al. 2011. Viral microRNA targetome of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell lines. Cell Host Microbe 10: 515–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R 2004. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432: 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP 2007. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. 2010. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ 2001. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science 293: 1146–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN 2004. The Drosha–DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev 18: 3016–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig JV, Esslinger S, Bottcher R, Saito K, Förstemann K 2009. Endo-siRNAs depend on a new isoform of loquacious and target artificially introduced, high-copy sequences. EMBO J 28: 2932–2944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K 2005. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev 19: 489–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A, Reynolds A, Jayasena SD 2003. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 115: 209–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S 2011. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D152–D157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Doudna JA 2012. TRBP alters human precursor microRNA processing in vitro. RNA 18: 2012–2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW 2004. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell 117: 69–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Zhou K, Smith AM, Noland CL, Doudna JA 2013. Differential roles of human Dicer-binding proteins TRBP and PACT in small RNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 6568–6576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnstaedt SD, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Luftig MA, Cullen BR 2010. Virally induced cellular microRNA miR-155 plays a key role in B-cell immortalization by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 84: 11670–11678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔC(T) method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E, MacRae IJ, Kirsch JF, Doudna JA 2008. Autoinhibition of human dicer by its internal helicase domain. J Mol Biol 380: 237–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Ma E, Zhou M, Robinson CV, Doudna JA 2008. In vitro reconstitution of the human RISC-loading complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 512–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz MM, Li L, Shamimuzzaman M, Wibowo A, Fang X, Zhu JK 2011. De novo-engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE) hybrid nuclease with novel DNA binding specificity creates double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 2623–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard PV, Ciaudo C, Marchais A, Li Y, Jay F, Ding SW, Voinnet O 2013. Antiviral RNA interference in mammalian cells. Science 342: 235–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniataki E, Mourelatos Z 2005. A human, ATP-independent, RISC assembly machine fueled by pre-miRNA. Genes Dev 19: 2979–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques JT, Kim K, Wu PH, Alleyne TM, Jafari N, Carthew RW 2010. Loqs and R2D2 act sequentially in the siRNA pathway in Drosophila. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 24–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall V, Parks T, Bagni R, Wang CD, Samols MA, Hu J, Wyvil KM, Aleman K, Little RF, Yarchoan R, et al. 2007. Conservation of virally encoded microRNAs in Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus in primary effusion lymphoma cell lines and in patients with Kaposi sarcoma or multicentric Castleman disease. J Infect Dis 195: 645–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NJ, Gregory RI 2013. Argonaute2 expression is post-transcriptionally coupled to microRNA abundance. RNA 19: 605–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF, Meng X, Paschon DE, Leung E, Hinkley SJ, et al. 2011. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat Biotechnol 29: 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Miyoshi T, Hartig JV, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2010. Molecular mechanisms that funnel RNA precursors into endogenous small-interfering RNA and microRNA biogenesis pathways in Drosophila. RNA 16: 506–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ 2005. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 12135–12140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Ogino A, Miyoshi T, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2013. Roles of R2D2, a cytoplasmic D2 body component, in the endogenous siRNA pathway in Drosophila. Mol Cell 49: 680–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Robine N, Liu Y, Liu Q, Lai EC 2011. R2D2 organizes small regulatory RNA pathways in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol 31: 884–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parameswaran P, Sklan E, Wilkins C, Burgon T, Samuel MA, Lu R, Ansel KM, Heissmeyer V, Einav S, Jackson W, et al. 2010. Six RNA viruses and forty-one hosts: viral small RNAs and modulation of small RNA repertoires in vertebrate and invertebrate systems. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Jan CH, Bartel DP 2007. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature 448: 83–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin LR, Zheng Q, Thekkat P, Yang J, Hannon GJ, Gregory BD, Tudor M, Cherry S 2013. Dicer-2 processes diverse viral RNA species. PLoS One 8: e55458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC 2005. Processing of pre-microRNAs by the Dicer-1–Loquacious complex in Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol 3: e235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander JD, Cade L, Khayter C, Reyon D, Peterson RT, Joung JK, Yeh JR 2011. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nat Biotechnol 29: 697–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin C, Nam JW, Farh KK, Chiang HR, Shkumatava A, Bartel DP 2010. Expanding the microRNA targeting code: functional sites with centered pairing. Mol Cell 38: 789–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin SH, Kim YB, Dittmer DP 2013. Latency locus complements microRNA 155 deficiency in vivo. J Virol 87: 11908–11911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol 81: 12836–12845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Yang JS, Azzam G, Liu JL, Lai EC 2013. Homeostatic control of Argonaute stability by microRNA availability. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 789–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Trombly MI, Chen J, Wang X 2009. Essential and overlapping functions for mammalian Argonautes in microRNA silencing. Genes Dev 23: 304–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]