Abstract

Violent offenders with psychopathy present a lifelong pattern of callousness and aggression and fail to benefit from rehabilitation programs. This study presents the first, albeit preliminary, evidence suggesting that some of the structural brain anomalies distinguishing violent offenders with psychopathy may result from physical abuse in childhood.

Keywords: Psychopathy, Structural magnetic resonance imaging, Childhood physical abuse

1. Introduction

Most violent offenders are males with a history of antisocial behavior that emerged in childhood, as indicated by a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) (Kratzer and Hodgins, 1999). Among these men, a subgroup additionally presents the syndrome of psychopathy (ASPD+P), characterized by a lack of empathy, callousness, shallow affect, superficial charm, and manipulation of others (Hare, 2003). Offenders with ASPD+P begin offending at a younger age, more often engage in instrumental aggression, commit more violent offenses than other offenders, and fail to benefit from rehabilitation programs (Hare, 2003). Importantly, both phenotypes emerge early in childhood (Frick and Viding, 2009).

Childhood physical abuse (CPA), defined as physical contact, constraint, or confinement designed to hurt or cause injury (Bremner et al., 2000), is experienced by many males who become persistent violent offenders (Widom, 1989) and who exhibit psychopathy in adulthood (Gao et al., 2010, Koivisto and Haapasalo, 1996). CPA has been associated with alterations in gray matter (GM) brain structures in childhood and in adulthood (McCrory et al., 2010). Alterations in similar structures have been reported in boys with conduct problems (Huebner et al., 2008) and violent offenders with psychopathy (Koenigs et al., 2011). We recently reported that violent offenders with ASPD+P displayed reduced GM volumes bilaterally in the anterior rostral prefrontal cortex and temporal poles compared with violent offenders with ASPD without psychopathy (ASPD−P) and healthy non-offenders (Gregory et al., 2012). The present study examined a sub-sample of these men to determine whether GM differences between ASPD+P and ASPD−P offenders were related to CPA.

2. Methods

Violent offenders were recruited from probation services in the United Kingdom (UK) and non-offenders from the community (Gregory et al., 2012). All completed diagnostic interviews and were rated on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) (Hare, 2003). The sub-sample examined in the present study included 13 healthy non-offenders; nine offenders with ASPD and PCL-R scores of 25 or higher, indicative of psychopathy (ASPD+P); and 15 offenders with ASPD and PCL-R scores less than 25 (ASPD−P). A PCL-R score of 25 or higher was used to identify the syndrome of psychopathy as cross-cultural research has found a generalized suppression of PCL-R scores in European samples that may artificially reduce the prevalence of psychopathy when a cut-off score of 30 is used (Cooke and Michie, 1999). These 37 men completed detailed interviews with one forensic psychiatrist to assess maltreatment before age 18 using the Early Trauma Inventory (Bremner et al., 2000). Total scores for physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and general trauma were calculated by summing the frequencies of each item positively endorsed (Bremner et al., 2000). ASPD+P, ASPD−P, and non-offender groups did not differ on age or IQ. ASPD+P and ASPD−P offenders had similar rates of substance use disorders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Group |

Group comparison |

Post-hoc test |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-offenders | Violent offenders |

|||||||

| NO (n=13) | ASPD−P (n=15) | ASPD+P (n=9) | Statistic | p-value | NO vs ASPD−P | NO vs ASPD+P | ASPD−P vs ASPD+P | |

| Age, mean (S.D.), years | 35.1 (8.0) | 35.0 (9.3) | 38.7 (6.0) | F2,34=0.7 | 0.52 | |||

| FSIQ, mean (S.D.) | 97.4 (13.8) | 91.0 (11.4) | 88.0 (10.6) | F2,34=1.8 | 0.18 | |||

| Total PCL-R score, mean (range) | 3.8 (0–10) | 15.2 (10–22) | 27.7 (25–31) | F2,34=67.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| PCL-R four facet model | ||||||||

| Facet 1 (Interpersonal) | 0.5 (0–4) | 1.5 (0–5) | 3.4 (2–6) | F2,34=14.5 | <0.001 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Facet 2 (Deficient affect) | 0.6 (0–2) | 2.9 (0–6) | 5.6 (2–8) | F2,34=20.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Facet 3 (Lifestyle) | 1.7 (0–5) | 5.3 (1–9) | 6.8 (3–9) | F2,34=20.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.19 |

| Facet 4 (Antisocial) | 0.2 (0–2) | 4.7 (1–8) | 9.0 (6–10) | F2,34=135.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total childhood abuse, mean (range) | 111.7 (1–439) | 193.9 (0–1272) | 838.2 (5–3346) | F2,34=2.6 | 0.091 | |||

| Childhood physical abuse | 27.8 (0–140) | 68.4 (0–306) | 347.7 (3–1344) | F2,34=6.0 | 0.006 | 0.18 | 0.002 | 0.027 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 0.5 (0–6) | 3.3 (0–44) | 2.1 (0–10) | F2,34=0.6 | 0.58 | |||

| Childhood emotional abuse | 73.7 (0–390) | 77.7 (0–810) | 362.9 (0–1440) | F2,34=0.9 | 0.40 | |||

| Early traumatic events | 9.7 (0–107) | 43.9 (0–216) | 74.5 (2–562) | F2,34=4.8 | 0.015 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.067 |

| History of substance use disorder | N/A | 10/15 | 3/9 | Χ2=2.5 | 0.21 | |||

Notes: FSIQ=full scale IQ; N/A=not applicable; NO=non-offenders; S.D.=standard deviation.

Scanning was conducted at the Centre for Neuroimaging Sciences, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK, on a 1.5 T GE Signa Excite MRI scanner as previously described (Gregory et al., 2012). Participants received a 14-min spoiled gradient-recalled echo high-resolution structural scan. One hundred twenty-four slices of 1.6 mm thickness were acquired (repetition time=34 ms, echo time=9 ms, flip angle=30°, field of view=20 cm). The acquisition matrix measured 256×192.

Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests. PCL-R and abuse data were log-transformed to normalize distributions. Modulated images were analyzed using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) for whole-brain comparisons. VBM is an automated image analysis technique that identifies focal differences in gray or white matter volume between subjects using voxel-wise comparisons of tissue probability (Ashburner and Friston, 2000). Whole brain group comparisons were performed within the framework of the general linear model using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM5, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Initial comparisons included the following three groups: ASPD+P offenders, ASPD−P offenders, and non-offenders. Post hoc t-tests (ASPD+P vs ASPD−P) were modeled within a full factorial design and corrected for non-stationary cluster extent using the VBM5 toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/), with an initial cluster-defining threshold of Z>2.4 and a corrected cluster-significance threshold of p=0.05. For further details, see Gregory et al. (2012).

3. Results

As shown in Table 1, scores for CPA differed across groups. Post hoc tests revealed that ASPD+P offenders reported significantly more CPA than ASPD−P offenders and non-offenders. Groups also differed on scores for early traumatic events. ASPD+P offenders reported more severe traumatic events than healthy participants but not ASPD−P offenders. There were no group differences in scores for sexual or emotional abuse.

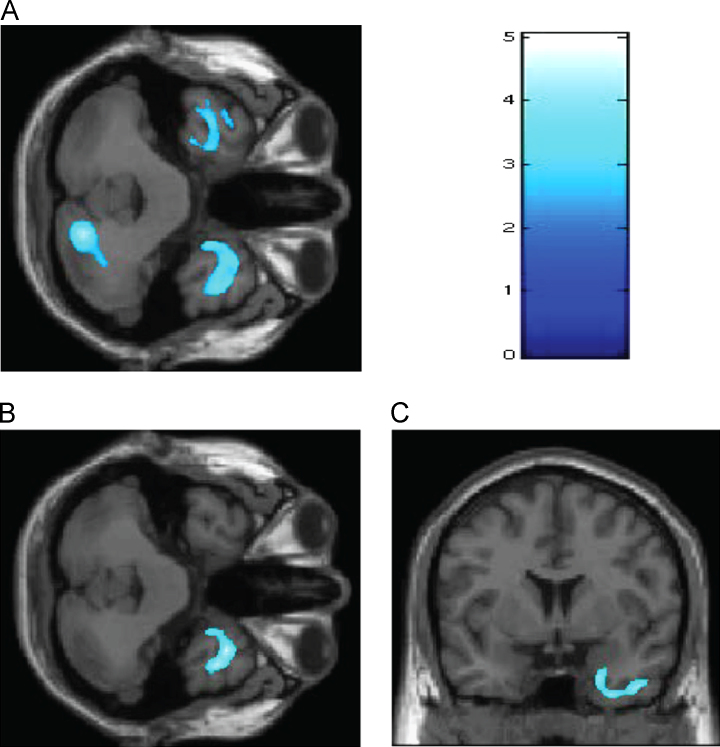

Compared with ASPD−P offenders, the ASPD+P offenders presented smaller GM volumes in bilateral temporal poles, right uncus, and right lobule VI of the posterior cerebellum (Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates of peak effect: x=18; y=−76; z=−35) (Fig. 1A). Re-running these analyses with CPA as a covariate of no interest showed that compared with ASPD−P offenders, the ASPD+P offenders displayed reduced volumes only in the right temporal pole and right uncus (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig. 1.

Gray matter differences between ASPD+P and ASPD−P violent offenders. (A) ASPD+P offenders demonstrated a reduction in bilateral temporal, right uncus, and right cerebellar regions compared with ASPD−P offenders. (B and C) After controlling for childhood physical abuse, significantly smaller gray matter volumes in ASPD+P were detected in the right temporal and uncal regions (Brodmann area 38; cluster size=6982; MNI coordinates of voxels of maximal statistical significance: x=35, y=10, and z=−41; corrected p-value=0.002). Color scale: 0–5 represent z scores.

4. Discussion

Consistent with past findings in psychopathy and conduct disorder (Huebner et al., 2008, Koenigs et al., 2011), violent offenders with ASPD+P showed smaller right temporal pole volumes than those with ASPD−P, even after controlling for CPA. The right temporal pole is implicated in the experience of self-referential emotions such as shame and embarrassment that foster pro-social behavior and moral learning, thereby promoting healthy socialization (Olson et al., 2007). These preliminary results suggest that the marked social impairment characteristic of psychopathy could be related to alteration of this structure.

Prior evidence points to reduced left temporal pole and cerebellar volumes in physically maltreated children (De Brito et al., 2013) and adolescents (Edmiston et al., 2011). In the present study, after controlling for CPA, the initial differences observed in these structures between ASPD+P and ASPD-P offenders disappeared. Lesion and imaging studies suggest that lobule VI cerebellar activation contributes to emotion recognition and empathic responding (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009), processes that are deficient in psychopathy. A possible interpretation of these findings is that CPA may have led to some of the anomalies of brain GM structures previously reported among men with psychopathy.

In addition to GM anomalies common to psychopathy and CPA, alterations in the corpus callosum and uncinate fasciculus have been observed in psychopathy and ASPD with high psychopathic traits (Koenigs et al., 2011) and in adults and children reporting CPA (McCrory et al., 2010). The preliminary results from this exploratory study, together with previous findings, suggest a testable hypothesis: Early in life, CPA initiates and/or promotes the development of psychopathic traits by altering GM and white matter. Alternatively, the severe conduct problems that accompany psychopathic traits in young children (Frick and Viding, 2009) may increase the likelihood of CPA (Trickett and Kuczynski, 1986, Whipple and Webster-Stratton, 1991, Burke et al., 2008). Prospective, longitudinal investigations are required to test these hypotheses.

While our sample was relatively small and CPA was self-reported, these results are the first to demonstrate differences in GM volumes between two distinct subtypes of violent offenders after taking CPA into account. The abuse histories of the participants were obtained using a clinician-administered interview, which has advantages over questionnaires (Bremner et al., 2000). Further, retrospective reports of CPA have been found to have relatively good validity (Hardt and Rutter, 2004). Pathological lying is a symptom of both ASPD and psychopathy, however, and the possibility that some participants were untruthful cannot be excluded. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first neuroimaging investigation of violent offenders that controlled for CPA. Moreover, we are aware of only a handful of structural neuroimaging studies of psychopathy or ASPD that considered the effects of substance misuse on GM structures (Raine et al., 2000, Müller et al., 2008, Glenn et al., 2010, Schiffer et al., 2011, Ermer et al., 2012). Although the groups in the present study were matched for substance misuse and for age and IQ, it is possible that they differed on other characteristics that influenced the results. This limitation is common to most brain-imaging studies.

References

- Ashburner J., Friston K.J. Voxel-based morphometry – the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J.D., Vermetten E., Mazure C.M. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for the measurement of childhood trauma: the early trauma inventory. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12:1–12. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<1::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J.D., Pardini J.A., Loeber R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:679–692. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke D.J., Michie C. Psychopathy across cultures: North America and Scotland compared. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:58–68. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito S.A., Viding E., Sebastian C.L., Kelly P.A., Mechelli A., Maris H., McCrory E.J. Reduced orbitofrontal and temporal grey matter in a community sample of maltreated children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston E.E., Wang F., Mazure C.M., Guiney J., Sinha R., Mayes L.C., Blumberg H.P. Corticostriatal-limbic gray matter morphology in adolescents with self-reported exposure to childhood maltreatment. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermer E., Cope L.M., Nyalakanti P.K., Calhoun V.D., Kiehl K.A. Aberrant paralimbic gray matter in criminal psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:649–658. doi: 10.1037/a0026371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick P., Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Raine A., Chan F., Venables P.H., Mednick S.A. Early maternal and paternal bonding, childhood physical abuse and adult psychopathic personality. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1007–1016. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn A.L., Raine A., Yaralian P.S., Yang Y. Increased volume of the striatum in psychopathic individuals. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory S., Ffytche D., Simmons A., Kumari V., Howard M., Hodgins S., Blackwood N. The antisocial brain: psychopathy matters. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:962–972. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J., Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare R.D. Second Ed. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto: 2003. Manual for the Revised Psychopathy Checklist. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner T., Vloet T.D., Marx I., Konrad K., Fink G.R., Herpetz S.C., Herpetz-Dahlmann B. Morphometric brain abnormalities in boys with conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:540–547. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M., Baskin-Sommers A., Zeier J., Newman J.P. Investigating the neural correlates of psychopathy: a critical review. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;16:792–799. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto H., Haapasalo J. Childhood maltreatment and adult psychopathy in light of file-based assessments among mental state examinees. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention. 1996;5:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer L., Hodgins S. A typology of offenders: a test of Moffitt's theory among males and females from childhood to age 30. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1999;9:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- McCrory E., De Brito S.A., Viding E. Research review: the neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1079–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J.L., Gänßbauer S., Sommer M., Döhnel K., Weber T., Schmidt-Wilcke T., Hajak G. Gray matter changes in right superior temporal gyrus in criminal psychopaths. Evidence from voxel-based morphometry. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2008;163:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson I.R., Ploaker A., Ezzyat Y. The Enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain. 2007;130:1718–1731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A., Lencz T., Bihrle S., Lacasse L., Colletti P. Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:119–127. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer B., Muller B.W., Scherbaum N., Hodgins S., Forsting M., Wiltfang J., Gizewski E.R., Leygraf N. Disentangling structural alterations associated with violent behavior from those associated with substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1039–1049. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley C.J., Schmahmann J.D. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2009;44:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett P.K., Kuczynski L. Children's misbehaviors and parental discipline strategies in abusive and nonabusive families. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple E.E., Webster-Stratton C. The role of parental stress in physically abusive families. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1991;15:279–291. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90072-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C.S. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]