Abstract

AIM: To systematically review pathological changes of gastric mucosa in gastric atrophy (GA) and intestinal metaplasia (IM) after Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication.

METHODS: A systematic search was made of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, ClinicalTrials.gov, OVID and the Cochran Library databases for articles published before March 2013 pertaining to H. pylori and gastric premalignant lesions. Relevant outcomes from articles included in the meta-analysis were combined using Review Manager 5.2 software. A Begg’s test was applied to test for publication bias using STATA 11 software. χ2 and I2 analyses were used to assess heterogeneity. Analysis of data with no heterogeneity (P > 0.1, I2 < 25%) was carried out with a fixed effects model, otherwise the causes of heterogeneity were first analyzed and then a random effects model was applied.

RESULTS: The results of the meta-analysis showed that the pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95%CI was 0.23 (0.18-0.29) between eradication and non-eradication of H. pylori infection in antral IM with a significant overall effect (Z = 8.19; P <0.00001) and no significant heterogeneity (χ2 = 27.54, I2 = 16%). The pooled WMD with 95%CI was -0.01 (-0.04-0.02) for IM in the corpus with no overall effect (Z = 0.66) or heterogeneity (χ2 = 14.87, I2 =0%) (fixed effects model). In antral GA, the pooled WMD with 95% CI was 0.25 (0.15-0.35) with a significant overall effect (Z = 4.78; P < 0.00001) and significant heterogeneity (χ2 = 86.12, I2 = 71%; P < 0.00001). The pooled WMD with 95% CI for GA of the corpus was 0.14 (0.04-0.24) with a significant overall effect (Z = 2.67; P = 0.008) and significant heterogeneity (χ2 = 44.79, I2 = 62%; P = 0.0003) (random effects model).

CONCLUSION: H. pylori eradication strongly correlates with improvement in IM in the antrum and GA in the corpus and antrum of the stomach.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori eradication, Gastric atrophy, Intestinal metaplasia, Pathological changes, Gastric mucosa, Meta-analysis

Core tip: This study reports the results of a meta-analysis conducted on a large number of articles using an extensive and thorough method. The inclusion of only high-quality relevant articles resulted in the identification of a very strong correlation between the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection and intestinal metaplasia of the antrum, and a strong correlation with gastric atrophy in both the antrum and the corpus of the stomach.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common cancer in the world and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, accounting for 10.4%[1]. The incidence and mortality of GC have fallen dramatically over the past 7 decades as a result of improved socioeconomic situations, sanitation, food preservation, as well as a decline in the incidence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[2-4]. Despite these declines, however, GC cure rates have not changed[4-6]. H. pylori infection has been known as a gastric carcinogen for over 10 years[7], and is the main cause of GC[8,9]. Infection triggers a multistep progression from chronic gastritis to gastric atrophy (GA), intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia, and finally invasive cancer. H. pylori is a spiral-shaped, microaerophilic, Gram-negative bacterium measuring approximately 3.5 × 0.5 microns that is the cause for the most common chronic bacterial infection in humans, infecting 50% of the world population[10,11].

H. pylori, which causes active chronic gastritis in all infected patients, leads to clinically relevant diseases, such as gastric and duodenal ulcers, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and GC, in 20% of infected carriers[12-17]. Furthermore, meta-analyses have indicated that the infection confers a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of GC development[18,19]. While the course of the infection depends on microbial virulence, host genetic factors and environmental factors, the clinical outcomes are determined by the type and intensity of gastritis, which can be categorized as either a simple benign gastritis, a duodenal ulcer phenotype, or a GC phenotype.

As H. pylori infection plays a causal role in the formation of GC, eradication of infection may play a role in GC prevention[15,16]. After H. pylori eradication, neutrophils disappear and mononuclear cells slowly return to normal[20]. However, the improvement in gastric mucosal lesions following eradication of H. pylori is not entirely clear. While the majority of studies have reported a reversal of atrophy, no reversal of IM has been shown. To further examine and resolve these discrepancies, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to determine if the eradication of H. pylori infection eliminates the precancerous lesions of GA and IM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, ClinicalTrials.Gov, OVID and the Cochran Library databases was made to identify relevant review articles, editorials, and original studies published through March 2013 using the following key words: H. pylori OR Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) OR HP, eradication OR treatment OR cure OR therapy, gastric atrophy OR atrophic OR GA OR intestinal metaplasia, clinical test, English-language. Data were independently extracted from each study by two of the authors working independently and using a predefined form; disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Published reports were selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis according to the following criteria: (1) English language publication; (2) prospective and randomized controlled trials on H. pylori eradication; (3) studies of adults testing positive for the presence of H. pylori prior to treatment and eradication of the infection documented both by histology and carbon (C) 14 urea breath test (UBT) or 13 C-UBT (sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 96%)[21]; (4) H. pylori eradication as the only treatment; and (5) gastric histology from at least three pathological specimens per sample processed for hematoxylin-eosin and modified Giemsa staining. Specimens were required to have been taken at baseline and at least 6 mo after treatment, evaluated separately for the antrum and corpus, and scored using the Sydney system[22] or the updated Sydney system[23]. Studies not meeting these criteria, those without data for retrieval, and duplicate publications were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Study quality and data extraction

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Risk of Bias table outlined in the Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook 5.0.1[24]. This method evaluates biases originating from sequence generation (selection bias), allocation sequence concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective outcome reporting (reporting bias). Every facet was judged as either yes, no, or unclear. A judgment of “yes” indicated that the method described was clear and correct, the information was complete, and indicated a low likelihood of bias. A judgment of “no” indicated a high likelihood of bias due to improper use of methods, unused allocation concealment, incomplete information, or selective reporting bias. An “unclear” judgment indicated that an assessment of bias could not be obtained due to insufficient descriptions. Judgments were assigned by two of the authors working independently, and discrepancies were remedied through discussions with a third investigator to obtain a consensus.

The data extracted from each study included the following: general article information (author, publication date, journal name, etc.); data to calculate the value of the total effect (treatment number, effective number, etc.); clinical heterogeneity of the study (sex, age, concurrent disease, treatment regimen, etc.); methodological heterogeneity of the study (design type, randomized, blinded, follow-up, quantity of and processing methods for pathological specimens, and methodology for histology scoring). Assessment of the degree of gastritis was performed according to the Sydney system[22] or the updated Sydney system[23]. For each graded variable, the following scores were assigned: 0 for absence and 1, 2 or 3 for mild, moderate or severe presence, respectively. The ultimate histology scores were used to weigh the severity of glandular atrophy or IM graded from 0 (normal) to 3 (markedly abnormal). Studies were reviewed and data extracted by two independent reviewers with knowledge of clinical medicine, epidemiology, and medical statistics, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. This process for data extraction was repeated to ensure accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Agreement on the selection of studies between the two reviewers was evaluated by the κ coefficient. Review Manager 5.2 and Begg’s test with STATA 11 were used to perform the meta-analysis to compare continuous variables, such as histological scores before and after H. pylori eradication. The inverse variance of the weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95%CIs for gastric mucosal histology scores was estimated for each study. The chi-square test and P-value analysis were used to indicate the presence of heterogeneity, and the size of the heterogeneity was tested with I². If there was no heterogeneity, a fixed effects model was applied. In cases where heterogeneity was indicated (P < 0.1, I² > 25%), causes for the heterogeneity were first analyzed; a random effects model was applied when the clinical and methodological heterogeneity could not be identified[25] and subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis was performed when the clinical or methodological heterogeneity was identified. In the presence of significant statistical heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine sample size, follow-up duration, number of biopsy samples, etc. To perform these analyses, meta-analyses were repeated following the exclusion of each individual study one at a time, in order to assess the overall effect of each study on the pooled WMD[26]. Overall effects were considered as statistically significant with a P-value < 0.05. Funnel plots were constructed to assess the likelihood of publication bias[27].

RESULTS

Search results

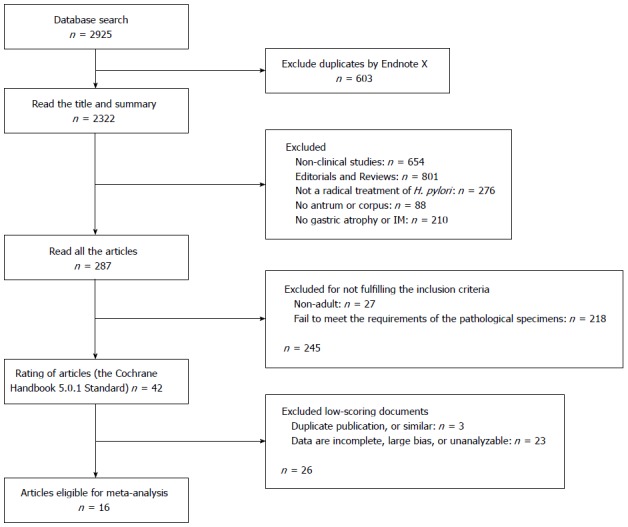

The selection of studies included in the meta-analysis is described in a flow chart shown in Figure 1. The initial search strategy yielded 2925 citations. Of these, 1034 were rejected as duplicates or the title suggested that the articles were not appropriate, and a further 1604 were excluded after initial review (editorials, review articles, animal experiments, non-English language, etc.). Of the remaining 287 candidate articles, 245 did not fully meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. A quality assessment of the 42 remaining papers led to elimination of a further 26 articles, leaving 16 studies eligible for the meta-analysis[28-43]. Initial agreement between the reviewers for the selection of relevant articles was high (κ = 0.96).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection of included studies. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; IM: Intestinal metaplasia.

Characteristics of included studies

The main characteristics of the 16 articles included in the meta-analysis are shown in Table 1. With the exception of one randomized control study[35], all studies were single-center observational studies conducted in different parts of the world, mostly Japan and Italy. All the papers gave data for the four histological parameters evaluated (GA and IM separately for gastric corpus and antrum). H. pylori eradication in these studies consisted of a standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors, bismuth-based triple regimens, or dual regimens for 1-2 wk. Two studies enrolled patients with early gastric cancer who underwent endoscopic mucosal resection without recurrence[33,34]. Histological scores were calculated twice in one study, as H. pylori eradication occurred at different time points in two different groups[36]. Another study calculated the histological scores of both the lesser and greater parts of the antrum and corpus before and after H. pylori eradication[31]. Initial agreement between the reviewers for the data extraction was high (κ = 0.95).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the 16 studies selected for meta-analysis

| Ref. | Author, year (country) | Study arms, n |

Histologic parameters |

||||||

| Eradicated | Not eradicated | Follow-up in year | Medication | GA |

IM |

||||

| Antrum | Corpus | Antrum | Corpus | ||||||

| [28] | Annibale B, 2000 (Italy) | 25 | 7 | 0.5 | BAM | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | 15 | 0.5 | BAM | ||||||

| 15 | 15 | 1 | BAM | ||||||

| [29] | Wambura C, 2004 (Japan) | 107 | 118 | 1 | L/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 107 | 118 | 2 | L/A/C | ||||||

| 107 | 118 | 3 | L/A/C | ||||||

| [30] | Annibale B, 2002 (Italy) | 8 | 0 | 0.5-1 | BAM | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 32 | 0 | 0.5-1 | BAM | ||||||

| [31] | Kamada T, 2005 (Japan) | 20 | 233 | 1 | O/L/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1767 | 1 | O/L/A/C | |||||||

| [32] | Tucci A, 1998 (Italy) | 10 | 0 | 1 | BAM | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 8 | 2 (lost) | 1 | BAM | ||||||

| [33] | Sung JJ, 2000 (China) | 226 | 245 | 1 | OAC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [34] | Ito M, 2002 (Japan) | 22 | 22 | 5 | PPI/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [35] | Lahner E, 2005 (Italy) | 38 | 36 | 6.7 | B-BTI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [36] | Toyokawa T, 2009 (Japan) | 241 | 19 | 5 | PPI/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [37] | Ohkusa T, 2001 (Japan) | 115 | 48 | 1-1.25 | PPI/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [38] | Iacopini F, 2003 (Italy) | 10 | 0 | 1 | OMC | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| [39] | Kamada T, 2003 (Japan) | 37 | 8 | 3 | OMC | Yes | No | No | No |

| [40] | Lu B, 2005 (China) | 92 | 62 | 3 | O/LAC | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| [41] | Ruiz B, 2001 (Colombia) | 29 | 21 | 1 | BAM | Yes | No | No | No |

| [42] | Yoshio O, 2004 (Japan) | 59 | 0 | 1 | O/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [43] | Yamada T, 2003 (Japan) | 87 | 29 | 0.83-4.17 | PPI/A/C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

A: Amoxicillin; B: Bismuth subcitrate; B-BTI: Bismuth-based triple regimen; C: Clarithromycin; GA: Gastric atrophy; IM: Intestinal metaplasia; L: Lansoprazole; M: Metronidazole; O: Omeprazole; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; BAM: Bismuth subcitrate, Metronidazole and Amoxicillin; OMC: Omeprazole, Metronidazole and Clarithromycin.

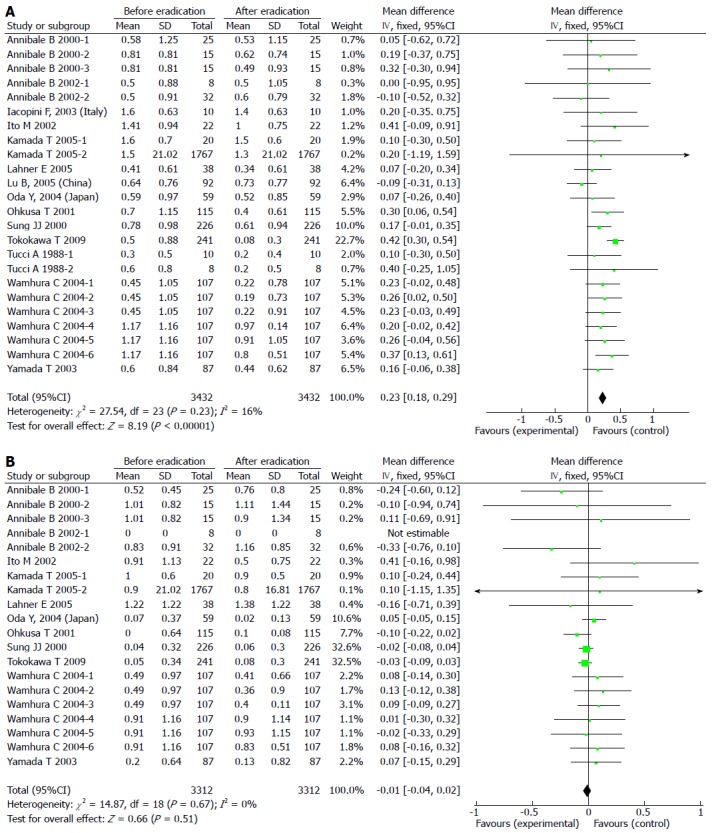

Intestinal metaplasia

Results of the analyses indicated no publication bias for reports on the effects of H. pylori eradication on IM in the antrum and corpus. The pooled WMD in the gastric antrum before and after H. pylori eradication with 95%CI was 0.23 (0.18-0.29) with a significant overall effect (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). For IM in the corpus, the pooled WMD with 95%CI was -0.01 (-0.04-0.02) with no significant overall effect (Figure 2B). There was no significant heterogeneity among any of these trials, therefore fixed effects models were used.

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing intestinal metaplasia in the antrum (A) and the corpus (B).

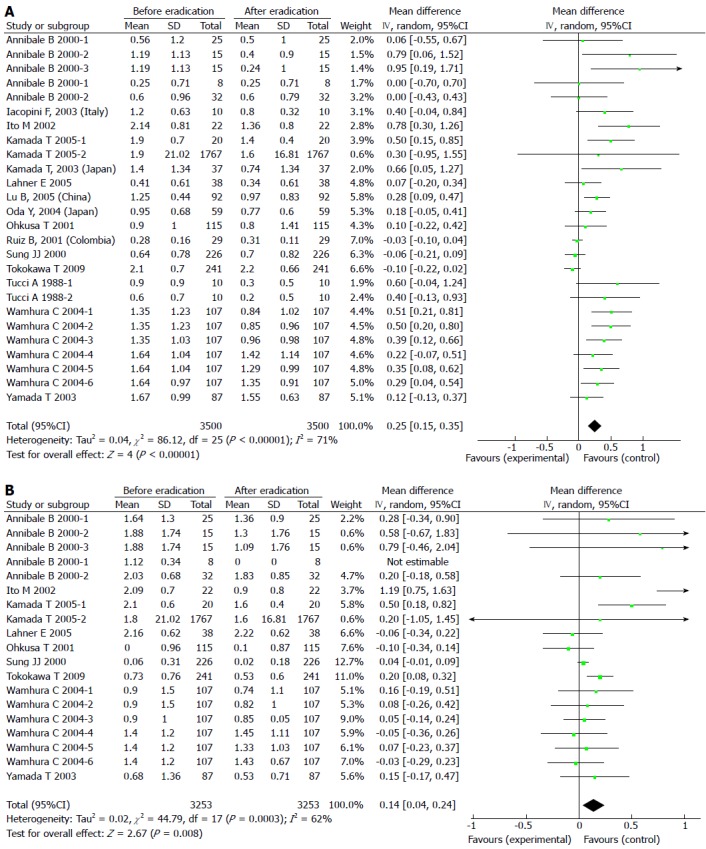

Gastric atrophy

Results of the analyses indicated no publication bias for reports on the effects of H. pylori eradication on GA in the antrum and corpus. The pooled WMD in the gastric antrum before and after H. pylori eradication with 95%CI was 0.25 (0.15-0.35) with a significant overall effect (P < 0.05) (Figure 3A). For GA in the corpus, the pooled WMD with 95%CI was 0.14 (0.04-0.24) with a significant overall effect (P < 0.05) (Figure 3B). There was significant heterogeneity among these trials, therefore random effects models were applied and multiple sensitivity analyses were performed. These analyses showed that the pooled WMD was not influenced by individual trials, thus no studies were excluded from the meta-analysis. These results indicate that the eradication of H. pylori aids in the reversal of both GA and IM in the antrum, but only reversal of GA, and not IM, was observed in the corpus.

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing gastric atrophy in the antrum (A) and the corpus (B).

DISCUSSION

Despite the numerous reports on the improvement of gastric mucosal lesions following H. pylori eradication[44-55], some inconsistencies still remain[48,51,56]. Thus, it is still disputed whether the pathology of gastric mucosa, particularly GA and IM, improves after curing of the H. pylori infection. In this meta-analysis, data from relevant published studies were pooled with an effort to determine if GA and IM of the stomach are reversible after H. pylori eradication, and therefore whether therapeutic intervention is possible, or if efforts should be more appropriately directed at prevention.

The results of this study indicated that H. pylori eradication did indeed have beneficial long-term effects on gastric pathologies, such as halting the progression of pre-neoplastic lesions in the antrum and corpus. More specifically, IM in the antrum and GA in both the antrum and corpus showed regression after eradication of H. pylori, although this effect was not seen in IM of the gastric corpus. The interpretation of this finding is not clear, but histological changes occurring after H. pylori eradication may play a role[44].

The results reported here differ from similar previously published meta-analyses[45,57]. There are several reasons that may explain this discrepancy. First of all, the previous analyses included a limited number of studies, whereas our analysis included 16 comparatively high-quality scoring studies. Second, the analysis by Rokkas et al[45] used the odds ratio as a statistical index, which may not be as precise as WMD for continuous variables. Additionally, there were errors in the analysis reported by Wang et al[57], which may have led to an incorrect conclusion.

The results of the current meta-analysis should be considered more reliable as a result of the extensive and thorough measures employed. For articles that merely reported results in chart format, the authors were contacted to obtain the raw data. Failure to obtain the raw data resulted in exclusion of the study to ensure reliability of the included data. Articles reporting varying treatment durations for the same group of patients were included as a separate set of data in the analysis, while taking into account the fact that medications had not been changed during the full course of treatment. Sensitivity analyses were performed to exclude the effects of different treatment courses, resulting in more accurate results[29]. Furthermore, data from articles that segregated results according to outcome were analyzed separately on the basis of the numbers of patients with successful eradication therapy in two groups[28,30-32], and only the patients with successful eradication were included in the analysis. Lastly, random effects models were used, which result in wider confidence intervals and, thus, a more conservative estimate of treatment effects.

The meta-analysis reported here is not without limitations. One inherent weakness involves the methodological flaws of the included studies, dependent on factors such as number of biopsy samples taken, method for histological classification of findings, sample size, and duration of follow-up. To alleviate such influences and unify the method of histological evaluation of biopsy samples, we selected only reports employing the updated Sydney system and had greater than three pathological samples of every specimen that were stained by hematoxylin-eosin methods. Another weakness is the inability to retrieve unpublished studies or published abstracts, due to the absence of a specific searching mechanism. However, we maximized the chances of detecting such studies by going through the references of the selected articles. Furthermore, although we used medical subject heading terms and keywords, some studies may have been missed, particularly studies in which the association of H. pylori infection with GA or IM was not the primary research question.

In conclusion, this study illustrates a very strong correlation between the eradication of H. pylori infection and improvement in IM in the gastric antrum but not in the corpus, in addition to a strong correlation with GA in both the antrum and the corpus. However, the follow-up periods of the analyzed studies are relatively short compared to the long process of mucosal carcinogenesis. Therefore, more high quality clinical studies with longer follow-up periods are necessary to assess the long-term benefit and whether the eradication of H. pylori infection delays disease progression.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most common cancer in the world and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Overall GC incidence and mortality have fallen dramatically over the past 7 decades, but despite that decline, the cure rates for GC have not changed. Therapeutic eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one factor contributing to these declines; however, this association is still debated.

Research frontiers

Although H. pylori eradication has been reported to improve gastric mucosal lesions, there are many studies with contradictory results. A clear understating of the role H. pylori eradication plays in the incidence and progression of GC will help guide therapies towards effective treatment or prevention.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that there is a very strong correlation between H. pylori infection and improvement in intestinal metaplasia in the antrum, but not the corpus, of the stomach. Furthermore, a strong correlation between H. pylori infection and improvement in gastric atrophy in the antrum and corpus was identified.

Applications

The results of this study confirm the association between H. pylori eradication and improvements in gastric pathologies. Although additional high quality clinical studies with longer follow-up periods are necessary to assess the long-term benefit of treatments, the findings implicate a viable treatment option for patients with intestinal metaplasia and gastric atrophy.

Terminology

Intestinal metaplasia is the transformation (metaplasia) of epithelium, usually of the stomach or the esophagus, to a type that bears some resemblance to the intestine, as seen in Barrett’s esophagus. Chronic H. pylori infection in the stomach and gastroesophageal reflux disease are seen as the primary instigators of metaplasia and subsequent adenocarcinoma formation.

Peer review

This article presents a well-designed meta-analysis of high quality studies evaluating the effect of H. pylori eradication on intestinal pathologies, namely intestinal metaplasia and gastric atrophy in the antrum and corpus of the stomach. The analyses show a strong correlation with improvement of intestinal metaplasia in the antrum, and gastric atrophy in the antrum and corpus, following eradication of H. pylori infection.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Shehata MMM, Sijens PE S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Oliveira C, Seruca R, Carneiro F. Genetics, pathology, and clinics of familial gastric cancer. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:21–33. doi: 10.1177/106689690601400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum S, Archer M. A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 1975;2:58–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 8:S4–66. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23:6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition - Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schistosomes , liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, Gillen D, Wirz A, Dahill S, Williams C, Ardill JE, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naylor GM, Gotoda T, Dixon M, Shimoda T, Gatta L, Owen R, Tompkins D, Axon A. Why does Japan have a high incidence of gastric cancer? Comparison of gastritis between UK and Japanese patients. Gut. 2006;55:1545–1552. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linz B, Balloux F, Moodley Y, Manica A, Liu H, Roumagnac P, Falush D, Stamer C, Prugnolle F, van der Merwe SW, et al. An African origin for the intimate association between humans and Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2007;445:915–918. doi: 10.1038/nature05562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pounder RE, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaser MJ. The versatility of Helicobacter pylori in the adaptation to the human stomach. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48:307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bardhan PK. Epidemiological features of Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:973–978. doi: 10.1086/516067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tepes B. Can gastric cancer be prevented? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60 Suppl 7:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Hulst RW, van der Ende A, Dekker FW, Ten Kate FJ, Weel JF, Keller JJ, Kruizinga SP, Dankert J, Tytgat GN. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastritis in relation to cagA: a prospective 1-year follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers EJ, Nelis GF, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Snel P, Goldfain D, Kolkman JJ, Festen HP, Dent J, Zeitoun P, Havu N, et al. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux oesophagitis treated with long term omeprazole reverses gastritis without exacerbation of reflux disease: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:12–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi M, Redline R, Nedrud J, Czinn S. Role of the host in pathogenesis of Helicobacter-associated gastritis: H. felis infection of inbred and congenic mouse strains. Infect Immun. 1996;64:238–245. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.238-245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malfertheiner P, Sipponen P, Naumann M, Moayyedi P, Mégraud F, Xiao SD, Sugano K, Nyrén O. Helicobacter pylori eradication has the potential to prevent gastric cancer: a state-of-the-art critique. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2100–2115. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price AB. The Sydney System: histological division. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:209–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1991.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brosnahan J, Jull A, Tracy C. Types of urethral catheters for management of short-term voiding problems in hospitalised adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD004013. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004013.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copas JB, Shi JQ. A sensitivity analysis for publication bias in systematic reviews. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10:251–265. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annibale B, Aprile MR, D’ambra G, Caruana P, Bordi C, Delle Fave G. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection in atrophic body gastritis patients does not improve mucosal atrophy but reduces hypergastrinemia and its related effects on body ECL-cell hyperplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wambura C, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Kuroda K, Maekawa S, Ebara S, Watanabe Y, Tamura T, Kasuga M. Influence of gastritis on cyclooxygenase-2 expression before and after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:969–979. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annibale B, Di Giulio E, Caruana P, Lahner E, Capurso G, Bordi C, Delle Fave G. The long-term effects of cure of Helicobacter pylori infection on patients with atrophic body gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1723–1731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamada T, Hata J, Sugiu K, Kusunoki H, Ito M, Tanaka S, Inoue K, Kawamura Y, Chayama K, Haruma K. Clinical features of gastric cancer discovered after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: results from a 9-year prospective follow-up study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1121–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucci A, Poli L, Tosetti C, Biasco G, Grigioni W, Varoli O, Mazzoni C, Paparo GF, Stanghellini V, Caletti G. Reversal of fundic atrophy after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1425–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sung JJ, Lin SR, Ching JY, Zhou LY, To KF, Wang RT, Leung WK, Ng EK, Lau JY, Lee YT, et al. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia one year after cure of H. pylori infection: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:7–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito M, Haruma K, Kamada T, Mihara M, Kim S, Kitadai Y, Sumii M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy improves atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: a 5-year prospective study of patients with atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1449–1456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahner E, Bordi C, Cattaruzza MS, Iannoni C, Milione M, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Long-term follow-up in atrophic body gastritis patients: atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are persistent lesions irrespective of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:471–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toyokawa T, Suwaki K, Miyake Y, Nakatsu M, Ando M. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection improved gastric mucosal atrophy and prevented progression of intestinal metaplasia, especially in the elderly population: a long-term prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:544–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohkusa T, Fujiki K, Takashimizu I, Kumagai J, Tanizawa T, Eishi Y, Yokoyama T, Watanabe M. Improvement in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in patients in whom Helicobacter pylori was eradicated. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:380–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-5-200103060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iacopini F, Consolazio A, Bosco D, Marcheggiano A, Bella A, Pica R, Paoluzi OA, Crispino P, Rivera M, Mottolese M, et al. Oxidative damage of the gastric mucosa in Helicobacter pylori positive chronic atrophic and nonatrophic gastritis, before and after eradication. Helicobacter. 2003;8:503–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamada T, Haruma K, Hata J, Kusunoki H, Sasaki A, Ito M, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M. The long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on symptoms in dyspeptic patients with fundic atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu B, Chen MT, Fan YH, Liu Y, Meng LN. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: a 3-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6518–6520. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz B, Garay J, Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Realpe JL, Mera R. Morphometric evaluation of gastric antral atrophy: improvement after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3281–3287. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshio O, Jun M, Mitsuru K, Yasuo M, Trumasa H, Yasuhiko O. Five-year follow-up study on histological and endoscopic alterations in the gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Endosc. 2004;16:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada T, Miwa H, Fujino T, Hirai S, Yokoyama T, Sato N. Improvement of gastric atrophy after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:405–410. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hojo M, Miwa H, Ohkusa T, Ohkura R, Kurosawa A, Sato N. Alteration of histological gastritis after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1923–1932. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G. The long-term impact of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric histology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 2:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou L, Sung JJ, Lin S, Jin Z, Ding S, Huang X, Xia Z, Guo H, Liu J, Chao W. A five-year follow-up study on the pathological changes of gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salih BA, Abasiyanik MF, Saribasak H, Huten O, Sander E. A follow-up study on the effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the severity of gastric histology. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1517–1522. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mera R, Fontham ET, Bravo LE, Bravo JC, Piazuelo MB, Camargo MC, Correa P. Long term follow up of patients treated for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2005;54:1536–1540. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.072009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arkkila PE, Seppälä K, Färkkilä MA, Veijola L, Sipponen P. Helicobacter pylori eradication in the healing of atrophic gastritis: a one-year prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:782–790. doi: 10.1080/00365520500463175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Ruiz B, Zarama G, Realpe JL, Malcom GT, Li D, Johnson WD, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You WC, Brown LM, Zhang L, Li JY, Jin ML, Chang YS, Ma JL, Pan KF, Liu WD, Hu Y, et al. Randomized double-blind factorial trial of three treatments to reduce the prevalence of precancerous gastric lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:974–983. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki H, Iwasaki E, Hibi T. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY, To KF, Ng EK, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244–1249. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J, Xu L, Shi R, Huang X, Li SW, Huang Z, Zhang G. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis. Digestion. 2011;83:253–260. doi: 10.1159/000280318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]