Abstract

Screening of small molecule libraries is an important aspect of probe and drug discovery science. Numerous authors have suggested that bioactive natural products are attractive starting points for such libraries, due to their structural complexity and sp3-rich character. Here, we describe the construction of a screening library based on representative members of four families of biologically active alkaloids (Stemonaceae, the structurally related cyclindricine and lepadiformine families, lupin, and Amaryllidaceae). In each case, scaffolds were based on structures of the naturally occurring compounds or a close derivative. Scaffold preparation was pursued following the development of appropriate enabling chemical methods. Diversification provided 686 new compounds suitable for screening. The libraries thus prepared had structural characteristics, including sp3 content, comparable to a basis set of representative natural products and were highly rule-of-five compliant.

Natural products (NPs) have played a central role in medicine for as long as humans have sought to cure and ameliorate disease1,2. Many have been fine-tuned by evolution for purposes that bear a mechanistic relationship to a given therapeutic need3. NPs are often potent, selective, and able to cross biological membranes although many do not adhere to common paradigms for oral absorption4 (it is worth recalling that NPs were specifically excluded from Lipinski's guidelines of drug-like properties5). For these reasons, NPs continue to inspire creativity in both medicinal chemistry and chemical synthesis.

As screening of small molecule libraries remains an important aspect of early stage drug and probe discovery, there has been interest in increasing the representation of NPs and related structures in libraries6-10. Approaches include the straightforward approach of collecting NPs or NP extracts from their natural sources, which requires access to libraries obtained from bioprospecting and, for extracts, a downstream deconvolution step. To supplement such sources, synthetic chemists have co-opted NP structures for construction of NP-like libraries. More often than not these efforts provide purpose-built libraries for biological indications closely related to known bioactivities of the NP itself11-13. Diversityoriented synthesis (DOS) has also been used to create NP-inspired libraries9,14,15. Some authors suggested that the higher sp3/sp2 content and rich stereochemistry typical of NPs and, by extension, libraries derived from them is correlated with suitability as drug candidates16-20. In all of these approaches, the complexity of NPs presents synthetic challenges that must be surmounted to provide screening libraries that contain chemotypes that can be modified in the case of attractive hits21,22.

We sought an approach to NP-like screening libraries that would balance the likelihood of finding molecules useful in the pursuit of new biology with synthetic tractability. We chose to focus on selected families of alkaloids, preferring those with established biological activity at multiple targets, hypothesizing that such families might embody a “privileged structure”23-28 that could be optimized for new biological properties following suitable modification. Thus, we created a nested set of synthetically derived cores that represented salient structural features of the NP starting point. These were further modified to produce “secondary scaffolds” that differ more substantially from the original structure but retain attractive elements of scaffold design. In previous work, we used these tenets to create a library based on Stemonaceae alkaloids that ultimately led to potent Sigma–1 ligands, an activity not known to be associated with this family of NPs29.

Here, we generalize this concept to structurally diverse alkaloids of the cylindricine, Amaryllidaceae, and lupin families. We sought to address the synthetic challenges presented by these families by repurposing a suite of thematically related chemical reactions to library construction, most of which were developed in the context of total synthesis. Additional method development ultimately allowed us to obtain diversifiable scaffolds unavailable directly from NP starting materials. Overall, we synthesized a total of 686 new compounds, of which >90% were prepared in >20 mg quantities and all in >90% purity.

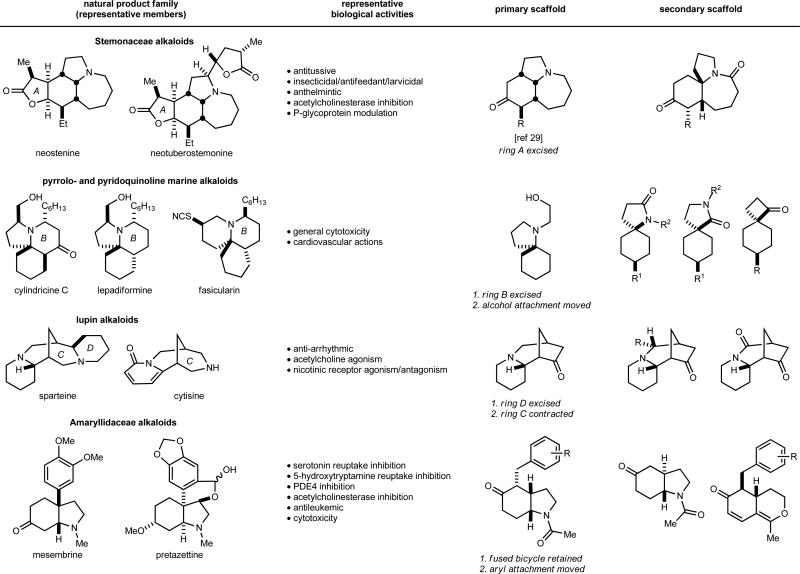

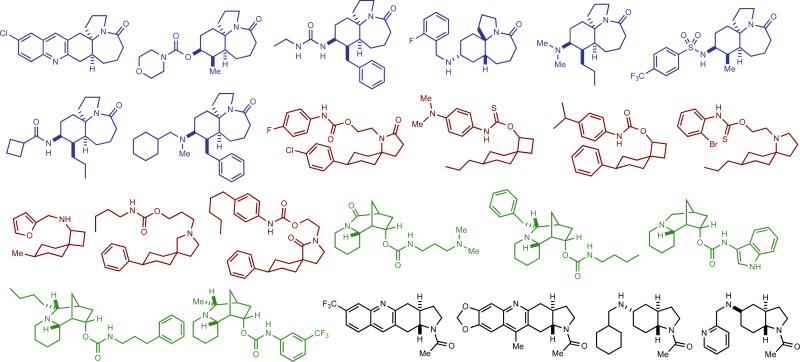

Figure 1 depicts scaffolds inspired by the architecture of four biologically active alkaloid families: (1) Stemonaceae alkaloids (exemplified by neostenine)30,31 (2) the structurally related cylindricine, lepadiformine, and fascicularine families of marine alkaloids (here, collectively called the cylindricine series)32, (3) the Amaryllidaceae alkaloid mesembrine33, and (4) sparteine, a lupin alkaloid34,35. Structurally, each starting alkaloid contains at least one fused pair of rings, but one spiro and one bridged ring system are also represented. Biologically, these classes represent a variety of reported activities, ranging from those described in traditional medicine for the NP source to pharmacologically verified and clinically used agents (Supplementary Table 1). According to the approach outlined above, each polycyclic alkaloid was simplified to the primary and secondary scaffolds indicated (Fig. 1). The secondary scaffolds contain the same number of rings as the central scaffold, but with different ring sizes and/or connectivities.

Figure 1. Strategic overview of NP families selected for library expansion and corresponding scaffold selection.

Each family of NPs is exemplified by 2–3 members and the biological activities cited are representative of each family as a whole. The reviews30-35 provide overviews of the biological landscape, with additional references provided in Supplementary Table 1. In each case, a primary scaffold embodies the minimal structural aspects of the NP family that were pursued. These involved removal of some features to enhance both versatility and synthetic accessibility. Secondary scaffolds (far right) represent more substantially modified variants of the primary scaffold, either through functional group or substitution changes or modification of ring structures.

RESULTS

Synthesis of scaffolds

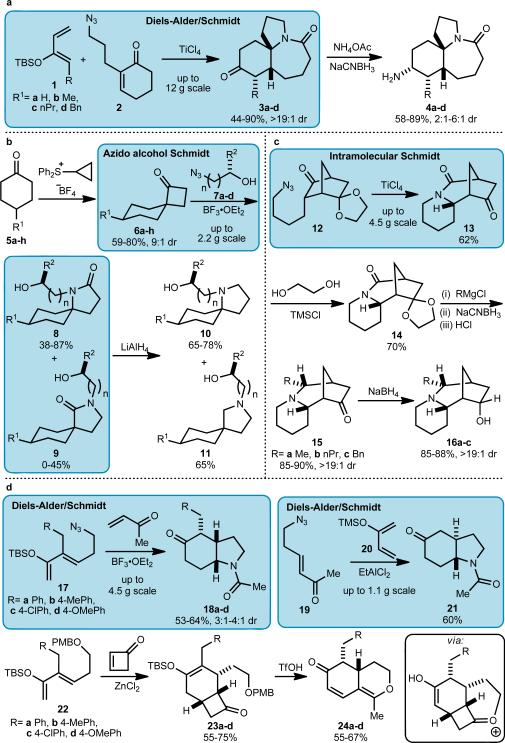

To make libraries containing 40–320 members each, it was necessary to develop enabling chemistries that would permit practical access to the desired chemotypes (Fig. 2). This was pursued using the azido-Schmidt conversion of keto azides to lactams as the primary unifying technology36. Four variations of this reaction were used to create the desired scaffolds: (1) the combined Diels–Alder/Schmidt reaction between a silyloxy diene and an azide-containing dienophile37 (Stemonaceae alkaloid series and one scaffold for the mesembrine series; Fig. 2a, d), (2) the reaction of a ketone with a hydroxylalkyl azide38 (cylindricine series; Fig. 2b), (3) the intramolecular Schmidt reaction of a ketone tethered to an azide39 (sparteine series; Fig. 2c), and (4) another combined Diels–Alder/Schmidt reaction, but this time one in which the azide is attached to the diene (the second mesembrine scaffold; Fig 2d).

Figure 2. Construction of primary and secondary scaffolds.

In each section, colored boxes indicate enabling chemistry developed for scaffold syntheses. (a) Synthesis of Stemonaceae alkaloid scaffolds using a Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction. (b) Cylindricine scaffolds were prepared by sulfur ylide-mediated spiroannulation followed by ring expansion using an azido alcohol variant of the Schmidt reaction. (c) Azide 12 was prepared from a previously reported C2-symmetrical diketone39 using an improved method (Supplementary Information) and converted to the tricyclic sparteine scaffolds using the intramolecular Schmidt reaction. (d) Two different variations of bicyclic analogs of mesembrine were prepared using a Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction. In addition, reaction of 22 with the interesting dienophile cyclobutenone43 followed by rearrangement afforded a non-nitrogenous scaffold 24. Full synthetic schemes, including experimental details and characterization data of representative compounds, are available in the Supplementary Information accompanying this paper.

The Diels–Alder/Schmidt sequence is particularly powerful as it extends the applicability of the ubiquitous Diels–Alder reaction by tying it to the in situ conversion of the new ring into a heterocycle. The other sequences rely in one case (Fig. 2b) on a spiroannulation step to afford a cyclobutanone (itself pressed into service as a scaffold; see below) that can be converted into the desired spirocyclic intermediates. Finally, the route in Fig. 2c parlays an advanced total synthesis intermediate into the scaffold 16. To use the Diels–Alder/Schmidt chemistry in panels a and d, we needed to explore new variations using highly substituted dienes. Schmidt reactions related to those shown in panels b and c were first developed during total synthesis efforts toward lepadiformine and cylindricine alkaloids39,40. The azido alcohol-mediated Schmidt reaction has been previously used for building a library of γ-turn mimetics41. We prepared most of the scaffolds in racemic form as there was no reason to favor a particular enantiomer for broad screening, often in straightforward biochemical assays (in a few cases, we did make scaffolds from L-configured amino-acid derivatives).

The Lewis acid-promoted reaction of unsubstituted diene 1a with 2 was previously reported37 but dienes 1b-d, which contain an additional element of diversity and are readily prepared in ≤3 steps from commercially available starting material, were unknown to engage in Diels–Alder/Schmidt chemistry prior to this work. All four dienes underwent the desired conversions, which were reproducible and scalable to provide up to 12 g of lactam with no loss of efficiency. Mechanistically, such reactions are believed to proceed by a Diels–Alder reaction, from which the product stereochemistry arises, followed by an intramolecular Schmidt reaction37. The relative stereochemistries of lactams 3b-d were confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Reductive amination with ammonium acetate provided amines 4a-d in good yield in 2–6:1 dr; the diastereomers of amines 4b-d were separated by reverse phase chromatography (the isomers of 4a were inseparable and not used for library synthesis). The relative stereochemistry of 4b and 4c was confirmed by X-ray crystallography of sulfonamide derivatives (Supplementary Information) and amine 4d was assigned by analogy.

Trost spiroannulation was used to create spirocyclic ketones 6a-h (Fig. 2b)42. Once in hand, these ketones were used as the basis of one sublibrary but our main objective was to convert them to the cylindricine-inspired substructures 8 and 9. This was accomplished by previously unexamined Schmidt reactions of 6a-h with hydroxyalkyl azides 7a-d. This led to a mixture of readily separable lactam regioisomers 8 and 9, thus affording a pair of useful scaffolds from ketones 6. The use of a two-carbon hydroxyalkyl azide led predominantly to formation of scaffolds 8, whereas three-carbon homologues afforded ca. 1:1 mixtures of constitutional isomers. Previous work has shown the selectivity of such reactions to be highly substrate-dependent; a discussion of the relevant topics has been published38. Additionally, lactams 8 and 9 were reduced to afford tertiary amine cores 10 and 11.

The tricyclic lactam core of the sparteine–inspired scaffolds (Fig. 2c) was prepared by intramolecular Schmidt reaction of azide 12, an intermediate in the total synthesis of sparteine39. Scale-up to 4.5 g quantities was possible by optimizing the previous route to compound 12. The multistep reduction shown in the scheme afforded amines 15a-c as single diastereomers, and further reduction with NaBH4 similarly led to isomerically pure alcohols 16a-c. The stereochemistry of the endo–selective Grignard addition and ketone reduction was confirmed by X-ray crystallography of a derived carbamate (see Supplementary Information).

The primary scaffold of the mesembrine series 18 was prepared in moderate yield and 3:1 to 4:1 dr by reacting previously unknown dienes 17 with methylvinylketone. These isomers proved inseparable and were not subjected to additional diversification. We similarly prepared secondary scaffold 21 by a modification of the previously reported Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction of diene 20 and azide-tethered enone 19 (Fig. 2d)37. Attaching the azide to either the diene or dienophile allows access to either the cis or trans fused scaffold, (cf. routes to 18 vs. 21). Hypothesizing that greater selectivity might be obtained with a more biased ring system we reacted 17 with the unusual dienophile cyclobutenone (introduced to the Diels–Alder reaction by Danishefsky43), but a complex mixture of products was obtained, with no desired lactam evident. For comparison, we prepared azide-less silyloxydiene 22 and submitted it to the Diels-Alder reaction conditions with cyclobutenone. In this case, the cycloaddition proceeded smoothly to afford bicyclic ketone 23 but surprisingly treatment with trifluoromethanesulfonic acid resulted in the formation of the previously unknown isochromenones 24 as single diastereomers. This reaction is previously unknown and could proceed via a retro-Michael reaction from the intermediate shown (an alternative enolization/electrocyclic ring-opening sequence is also possible but available evidence does not currently allow us to differentiate between the possibilities).

Library construction

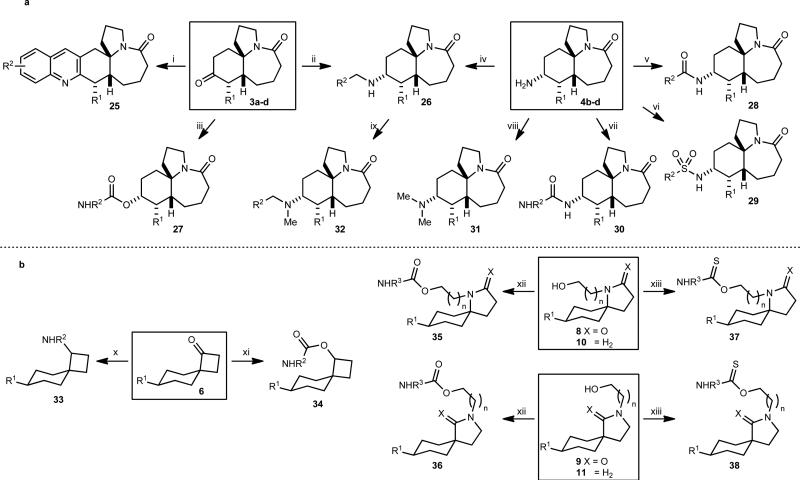

We took three main tacks toward diversifying our scaffolds: direct conversion of ketones to additionally fused heterocycles or amines, conversion of alcohols to carbamates, or decoration of amines as amides, sulfonamides, or ureas. These methods were chosen because they increase structural diversity, provide various degrees of hydrogen-bonding capabilities, and yield functional groups consistent with probe or drug development.

For the Stemonaceae-derived library, scaffold 3a gave quinolines 25 by a modified Friedländer reaction and secondary amines 26 by reductive amination with various benzylamines (Fig. 3a). The analogous reactions with scaffolds 3b-d resulted in an inseparable mixture of diastereomers, which were not pursued. Further diversification was achieved by reducing ketones 3a-d with L-Selectride→ to generate the corresponding alcohols with excellent diastereoselectivity (relative stereochemistry of the major product was determined by X-ray crystallography); these were used to prepare a library of carbamates 27. Direct reaction of the alcohol with isocyanates resulted in the formation of an unidentified by-product that co-eluted with the carbamate product upon purification. However, by first converting the alcohol to the corresponding para-nitrobenzyl carbonate, subsequent reaction with a wide range of amines resulted in a much cleaner and more effective preparation of library members. Amine scaffolds 4b-d were used to synthesize sublibraries of amides 28, sulfonamides 29, ureas 30 and secondary amines 26, while tertiary amine libraries were obtained either by reductive amination of secondary amines 26 with formaldehyde, or by Eschweiler-Clarke reaction of primary amines 4b-d.

Figure 3. Library construction from Stemonaceae and cylindricine alkaloidinspired scaffolds.

(a) Ketone scaffolds 3a-d and amines 4b-d were converted into libraries of quinolines, amines, amides, sulfonamides, ureas and carbamates; the key scaffolds are indicated by boxes. (b) Ketone scaffolds 6, lactams 8 and 9, and amines 10 and 11 were converted into a series of libraries of amines, carbamates and thiocarbamates. A total of 499 unique structures, each obtained in >90% purity (HPLC, UV detector at 214 nm) and >20 mg quantities were obtained. Scaffold (number of final products obtained): 3a-d (131), 4c-d (191), 6 (112), 8 (19), 9 (12), 10 (32), 11 (2). (i) 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde, Fe0, 0.1 M aq HCl, EtOH, 85 °C; then 3a-d, KOH, 85 °C; (ii) amine, AcOH, Na(OAc)3BH, CH2Cl2, rt; (iii) a) L-Selectride, THF, −78 °C to rt, 90–95%, 9:1– ≥19:1 dr, (b) 4-nitrophenylchloroformate, pyridine, rt, 55–76%, (c) R2NH2, CH2Cl2, rt; (iv) R2CHO, AcOH, Na(OAc)3BH, CH2Cl2, rt; (v) R2CO2H, EDC, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; (vi) R2SO2Cl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt; (vii) R2N=C=O, PhMe, rt; (viii) H2C=O, HCO2H, 95 °C; (ix) H2C=O, AcOH, Na(OAc)3BH, CH2Cl2, rt; (x) R2NH2, DCE, microwave, 150 °C; (xi) a) NaBH4, THF, MeOH, rt, 94–97%, (b) R2N=C=O, Et3N, THF, rt; (xii) R2N=C=O, Et3N, THF, rt; (xiii) R2N=C=S, NaH, THF, rt.

Spirocyclic ketone scaffolds 6 were converted into libraries of amines 33 by microwave-assisted reductive amination, and libraries of carbamates 34 by reduction with NaBH4 followed by reaction with isocyanates (Fig. 3b). Similarly, the alcohol moiety of lactams 8 and 9 and cyclic amines 10 and 11 were reacted with isocyanates and isothiocyanates to produce libraries of carbamates 35 and 36 and thiocarbamates 37 and 38, respectively.

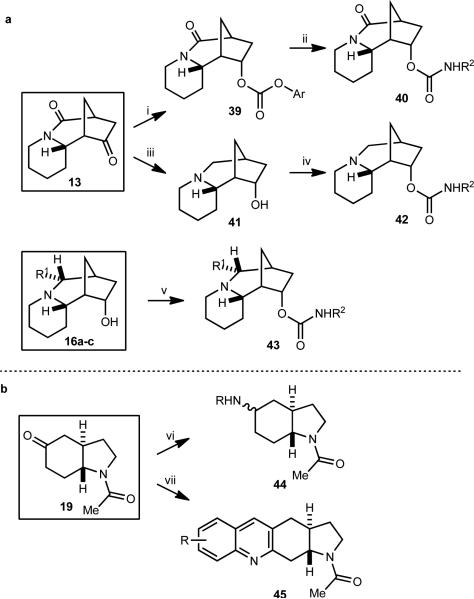

The ketone of scaffold 13 was stereoselectively reduced to afford the corresponding endo alcohol (Fig. 4a), the structure of which was determined by X-ray of the corresponding para-bromobenzoyl ester (see Supplementary Information). The alcohol was converted into a library of carbamates 40 by carbonate formation and subsequent reaction with a range of amines. The corresponding library containing a basic amine in the ring system was prepared by double reduction with LiAlH4 in THF, giving 41, which was further diversified into carbamates 42 by microwave-promoted reaction with isocyanates. Similar treatment of 16a-c led to libraries exemplified by 43.

Figure 4. Library construction from sparteine and mesembrine-inspired scaffolds.

(a) Library construction from sparteine-inspired scaffolds led to carbamates generated both from lactam 13 directly or by first converting it to the amine-containing scaffold 41. Similar chemistry could be used on the additional alkyl-group-containing scaffolds 16a–c. (b) Amide scaffold 19 was converted into amine and quinoline libraries. A total of 132 unique structures, each obtained in >90% purity (HPLC, UV detector at 214 nm) and >10 mg quantities were obtained. Scaffold (number of final products obtained): 13 (44), 16a-c (52), 19 (36). (i) a) NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 88%, >19:1 dr, (b) 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate, pyridine, THF, rt, 95%; (ii) R2NH2, DCE, rt; (iii) LiAlH4, THF, reflux, 80%; (iv) R2N=C=O, MeCN, microwave, 110 °C; (v) R2N=C=O, THF, rt; (vi) RNH2, AcOH, Na(OAc)3BH, THF; (vii) 2-nitrobenzaldehyde, Fe0, 0.1M HCl, EtOH, 85 °C; then 19, KOH, 85 °C.

Reductive amination of mesembrine-inspired scaffold 19 provided the corresponding secondary amines 44 in 2:1 to 1:1 dr (Fig. 4b). We ascribe the poor stereoselectivity to the relatively flat nature of the trans ring-fused system inherent in 19. In this case, the amine diastereomers were separable by reverse phase chromatography, which allowed us to incorporate a modest number of amines containing this scaffold into our library (relative stereochemistries were determined by 2D NMR). The use of anilines in the reductive amination resulted in inseparable mixtures of diastereomeric products, which were unsuitable for our screening requirements. A library of quinolines 45 was also synthesized by reacting scaffold 19 with either substituted 2-aminobenzaldehydes or 2-aminobenzophenones or acetophenones.

Cheminformatic analysis

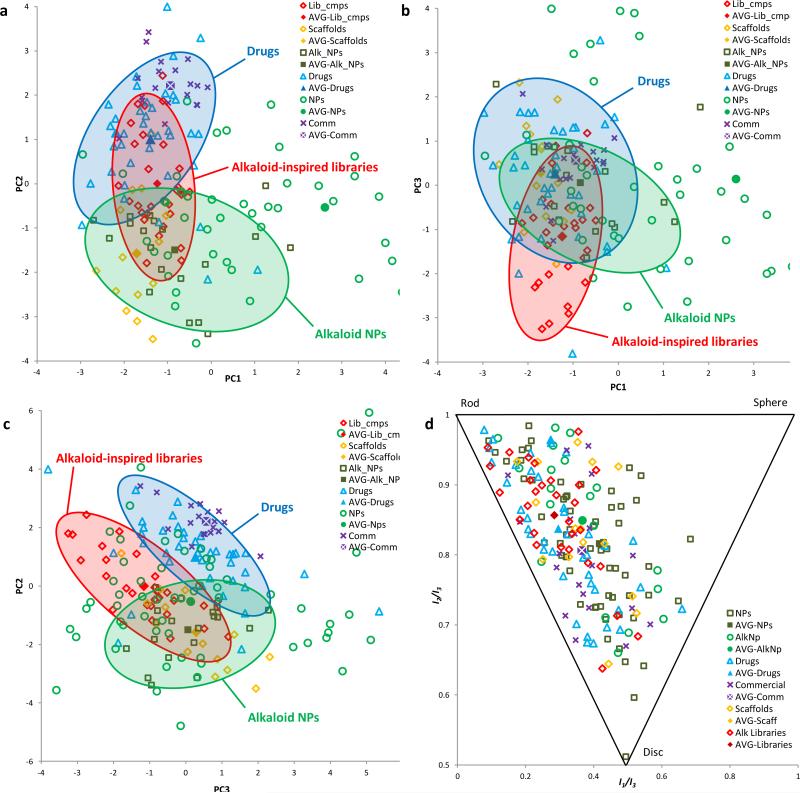

The chemical properties of our alkaloid-inspired libraries were analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA), a statistical tool to condense multi dimensional chemical properties (e.g., MW, logP, ring complexity) into single dimensional numerical values (principal components), allowing greater ease of comparison with different sets of compounds44. This analysis was performed on a representative sample of scaffolds and library members summarized in Fig. 5 (full list in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), which compared them to a selection of alkaloid NPs and a reference set of drugs, NPs, and commercial drug-like compounds using the protocols employed by Tan45. The parameters that have the greatest influence on principal component 1 (PC1) are molecular weight, number of oxygen atoms, number of hydrogen bond acceptors, and topological polar surface area (tPSA). Together, these parameters have the effect of moving compounds to the right in plots PC1 v PC2 and PC1 v PC3. The descriptors with the largest loading on PC2 are the number of nitrogen atoms, number of aromatic rings, and the number of ring systems, which shift compounds upward in plots PC1 v PC2 and PC2 v PC3. In contrast, the nStMW parameter (defined as the number of R – S stereocenters, this may be viewed as a rough descriptor of stereochemical complexity), shifts compounds downward in these plots. Finally, PC3 is affected to the greatest degree by XLogP (calculated octanol/water partition coefficient), number of rings, and ALOGPs (an alternative logP calculation), which together shift compounds in a negative direction along the PC3 axis in plots PC1 v PC3 and PC2 v PC3, and ALOGpS (calculated aqueous solubility), which shifts compounds in a positive direction in these plots.

Figure 5. Representative selection of library compounds used in cheminformatic analyses.

For a full list of scaffold and library compounds used in this analysis, see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4.

In two of the three variations, the data show significant overlap between our alkaloid-inspired library compounds with both drug and NP regions (Fig. 6a,b). In the PC2 vs. PC3 plot, there is less overlap between our library compounds and commercial drug space, but the compounds still overlap considerably with natural alkaloid space and abuts drug space (Fig 6c). This might be expected to naturally arise from the combination of two different modes of synthetic chemistry: the natural-product inspired routes that led to the key scaffolds vs. the diversity generating steps that followed in the library expansion phase.

Figure 6. Cheminformatic analysis of alkaloid-inspired scaffolds and library members.

Structural and physiochemical properties of a representative selection of synthesized scaffolds (14 compounds, yellow diamonds) and library members (29 compounds, red diamonds) were compared with those of alkaloid NPs (20 compounds, green squares) and an established reference set48 of drugs (40 compounds, blue triangles), commercially available drug-like molecules (20 compounds, purple crosses) and NPs (60 compounds, green circles) using principal component analysis (PCA) and principal moment of inertia (PMI) analysis. The hypothetical average (mean) structure for each series is also plotted (AVG-). (a) PCA plot of PC1 v PC2. (b) PCA plot of PC1 v PC3. (c) PCA plot of PC2 v PC3. (d) PMI plot showing the 3-dimensional shape of the lowest energy conformer of each compound. The shaded red, green, and blue areas outline the regions of the plot where the majority of our alkaloid inspired libraries, alkaloid NPs, and drugs, respectively, are located.

Principal moment of inertia (PMI) analysis46 was also used to compare the 3-dimensional shapes of the lowest energy conformations of our scaffolds and library members with the above reference sets45. Our compounds were found to lie along the roddisc side of the triangle, with a preference for the rod vertex (Fig. 6d). We note that drugs and the commercially screening libraries represented in the reference sets also reside in this region of the plot46.

These analyses suggest that our scaffolds and library compounds are similar to NPs, particularly alkaloid NPs, while also sharing attractive properties of drugs believed to be compatible with bioavailability. We note that the fraction of carbon atoms with an sp3 center (Fsp3) in our scaffolds (0.77) and library compounds (0.66) is very similar to the values obtained for our reference NPs (0.64) and alkaloids (0.65), and substantially higher than that for drugs (0.41) (Supplementary Table 2). Alkaloids (average MW 319, rotatable bonds 2.8) are generally smaller and more rigid than non-alkaloid NPs (629, 9.7), and more closely resemble our library compounds (355, 4.1). Although we did not particularly set out to adhere to any filters for drug-likeness in our design, we point out that 72% of our library compounds satisfied each of Lipinski's rules of 5, with 100% meeting 3 out of 4 of the criteria. Moreover, all library members fulfilled Veber's requirements for good oral bioavailability (≤10 rotatable bonds; ≤140 Å2 total polar surface area)47.

DISCUSSION

We have described one approach to balancing two concerns that arise in the development of libraries for biological screening: (1) the desire to provide compound collections that are different enough from existing libraries to inform interesting new biology while (2) dealing with the sheer vastness of chemical space, which makes it hard to create useful new bioactive molecules that are strikingly different from typical drug-like libraries. Using four alkaloids as inspiration agents, we used straightforward reaction sequences and moderately advanced synthetic intermediates to generate scaffold structures that were easily converted to libraries using parallel synthesis technology. The particular routes combine azide-mediated methods for the incorporation of nitrogen into organic frameworks with established ketone syntheses. Regarding the latter, we used one very well known reaction for the generation of fused ring systems (the Diels–Alder) and a powerful but somewhat underutilized method for generating spirocycles (the Trost spiroannulation). Overall, a total of 686 previously unknown structures were synthesized, comprising 55 separate scaffolds and 631 analogues. Of these, 266 (39%) of the compounds contained a basic nitrogen atom (ranges: 21% for the Stemonaceae alkaloid libraries to 68% of those derived from mesembrine). Overall, >90% of the library members were obtained in the 20 mg quantities and 90% purities that we had initially targeted (with the remainder achieving the purity goal but only being obtained in 10–20 mg quantities), with all of the compounds being >90% diastereomerically pure. The synthetic routes developed are amenable with both hit re-synthesis and downstream structure–activity relationships studies, both critical for real-world applications of small-molecule libraries.

The computational assessment of our libraries shows that the new compounds have many of the attributes that some authors have proposed to arise from using NPs in the first place, notably high sp3 counts relative to commercial libraries and comparable to those in a previously used NP set48. This feature naturally arose from the selection of alkaloid-based scaffolds and reflects the choice of targets in the first place. In fact, the slight drop in average sp3 content in the libraries made vs. the scaffolds themselves can be attributed to our selection of common “medicinal chemistry” subunits (e.g., aromatics) for our specific diversification efforts. On the other hand, the observation that the libraries were highly Lipinski- and Veber-compliant may be viewed as a surprise, given the conventional viewpoint that NPs have very different chemical properties from synthetically derived drug scaffolds. Overall, the PCA and PMI analysis support that the primary goal of this project was achieved insofar as we created libraries different enough from highly occupied drug discovery space to be interesting (and thus addressing our mission of “probing chemical space”), but not so different as to lack potential in screens. The ultimate determination of this potential through screening against a variety of targets (e.g., by submission into the Small Molecule Repository of the US National Institutes of Health) and the extension of the concept to other libraries are currently being pursued.

METHODS

General procedures for the key Schmidt reactions employed in the syntheses of scaffolds 3, 8, 9, 13, 18 and 21 are described below. All reactions were performed using flame-dried glassware under an argon atmosphere. Additional experimental details and analytical data for scaffold synthesis and library preparation are in the Supplementary Methods, along with full details of the cheminformatic analysis. CAUTION: The authors remind all experimentalists contemplating use of these methods to follow established safety protocols in the use of alkyl azides and their precursors.

General procedure for Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction for preparation of scaffolds 3 (Stemonaceae alkaloid series)

Titanium tetrachloride (1 M solution in dichloromethane, 2.5 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of azide 2 (1 equiv.) and silyloxydiene 1a-d (2.5 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane (0.06 M w.r.t. azide) at 0 °C under argon. The resulting red/brown solution was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h, then allowed to warm slowly to room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was then quenched with water and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The organic layer was removed, and the aqueous extracted with dichloromethane (×3). The combined organics were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to afford a brown oil. The crude product was purified by chromatography (silica gel, 95:5 ethyl acetate: methanol) to afford lactams 3a-d.

General procedure for azido-alcohol Schmidt reaction for preparation of scaffolds 8 and 9 (cylindricine series)

Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (5 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of spiro[3.5]nonan-1-one 6a-h (1 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane (0.15 M w.r.t. spirononanone) at −78 °C under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at −78 °C, then a solution of hydroxyalkyl azide (3 equiv.) in dichloromethane (1.5 M) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 3 h, then allowed to warm slowly to room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was then concentrated under reduced pressure and the resulting oil was dissolved in 15% aqueous potassium hydroxide solution and stirred for 30 min. The reaction mixture was then extracted with dichloromethane (×3). The combined organics were washed with water, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated. The crude product was purified by automated chromatography (silica column, 0–100% ethyl acetate in hexanes) to afford lactams 8 and 9.

Alkyl azide Schmidt reaction for preparation of scaffold 13 (sparteine series)

Titanium tetrachloride (20.7 mL, 188.5 mmol, 5 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of azide 12 (10 g, 37.7 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane (350 mL) at 0 °C under argon. A yellow precipitate was formed. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 24 h, and then quenched with water. The aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to give an oil. The crude product was purified by chromatography (silica gel, 100% ethyl acetate) to afford lactam 13 (4.5 g, 62%) as a colorless solid.

General procedure for Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction for preparation of scaffolds 18 (mesembrine series)

Methyl vinyl ketone (1 equiv.) was added to a solution of silyloxydiene 20 (1.5 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane (0.4 M w.r.t. diene) and the reaction mixture cooled to −78 °C. Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (1.5 equiv.) was then added and the reaction mixture stirred at –78 °C for 4 h then warmed to room temperature. A further aliquot of boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (2 equiv.) was then added and the reaction mixture stirred at room temperature for an additional 16 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with dichloromethane and quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous NH4Cl, water and brine, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated. The crude product was purified by automated column chromatography (silica column, 0 to 100% ethyl acetate in hexanes, then 90:10 dichloromethane:methanol) to afford lactams 18.

Diels-Alder/Schmidt reaction for preparation of scaffold 21 (mesembrine series)

Ethylaluminium dichloride (1 M solution in hexane, 25 ml, 1 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of trimethylsilyloxy butadiene 20 (3.5 g, 25 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) and azide 19 (1.4 g, 10 mmol, 1 equiv.) in anhydrous dichloromethane (15 mL) under argon at −78 °C. After the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 2 h then gradually warmed to room temperature and stirred for a further 16 h, then quenched with water and diluted with dichloromethane (100 mL). The combined organics were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL) and brine (50 mL), dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated. The crude product was purified by chromatography (silica column, 100% ethyl acetate) to afford lactam 19 (800 mg, 45%) as a light yellow oil.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Porubsky and Benjamin Neuenswander for purification of library compounds. Financial support from the US Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41 GM089164 (Pilot-scale Libraries Initiative) and 5P50GM069663 (KU Chemical Methodologies and Library Development center)) and an NSF-MRI grant (CHE-0923449) for the purchase of an X-ray diffractometer is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions M. C. M., J. N. P., D. R., G. S. and J. A. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. M. C. M., J. N. P., D. R. and G. S. performed the synthesis and characterization. J. L. W. and M. C. M. performed the cheminformatic analysis, and V.W.D. performed and analyzed the X-ray structures. M. C. M. and J. A. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Last 25 Years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. doi:10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:475–516. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. doi:10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson I, Anderson EA. Chemistry. The renaissance of natural products as drug candidates. Science. 2005;310:451–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1116364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganesan A. The impact of natural products upon modern drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boldi AM. Libraries from natural product-like scaffolds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas GL, Johannes CW. Natural product-like synthetic libraries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.05.022. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camp D, Davis RA, Evans-Illidge EA, Quinn RJ. Guiding principles for natural product drug discovery. Future Med. Chem. 2012;4:1067–1084. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.55. doi:10.4155/fmc.12.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachance H, Wetzel S, Kumar K, Waldmann H. Charting, Navigating, and Populating Natural Product Chemical Space for Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:5989–6001. doi: 10.1021/jm300288g. doi:10.1021/jm300288g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuegg J, Cooper MA. Drug-likeness and increased hydrophobicity of commercially available compound libraries for drug screening. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12:1500–1513. doi: 10.2174/156802612802652466. doi:10.2174/156802612802652466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Njardarson JT, Gaul C, Shan D, Huang X-Y, Danishefsky SJ. Discovery of Potent Cell Migration Inhibitors through Total Synthesis: Lessons from Structure.Activity Studies of (+)-Migrastatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1038–1040. doi: 10.1021/ja039714a. doi:10.1021/ja039714a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szpilman AM, Carreira EM. Probing the biology of natural products. Molecular editing by diverted total synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:9592–9628. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904761. doi:10.1002/anie.200904761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wetzel S, Bon RS, Kumar K, Waldmann H. Biology-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:10800–10826. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007004. doi:10.1002/anie.201007004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke MD, Schreiber SL. A Planning Strategy for Diversity-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:46–58. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300626. doi:10.1002/anie.200300626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huigens RW, et al. A ring-distortion strategy to construct stereochemically complex and structurally diverse compounds from natural products. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:195–202. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1549. doi:10.1038/nchem.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YK, et al. Relationship of stereochemical and skeletal diversity of small molecules to cellular measurement space. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14740–14745. doi: 10.1021/ja048170p. doi:10.1021/ja048170p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelat AA, Guy RK. Scaffold composition and biological relevance of screening libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:442–446. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0807-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. doi:10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemons PA, et al. Quantifying structure and performance diversity for sets of small molecules comprising small-molecule screening collections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:6817–6822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovering F. Escape from Flatland 2: complexity and promiscuity. MedChemComm. 2013;4:515–519. doi:10.1039/c2md20347b. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nandy JP, et al. Advances in Solution- and Solid-Phase Synthesis toward the Generation of Natural Product-like Libraries. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1999–2060. doi: 10.1021/cr800188v. doi:10.1021/cr800188v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacLellan P, Nelson A. A conceptual framework for analysing and planning synthetic approaches to diverse lead-like scaffolds. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:2383–2393. doi: 10.1039/c2cc38184b. doi:10.1039/c2cc38184b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans BE, et al. Methods for drug discovery: development of potent, selective, orally effective cholecystokinin antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1988;31:2235–2246. doi: 10.1021/jm00120a002. doi:10.1021/jm00120a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeSimone RW, Currie KS, Mitchell SA, Darrow JW, Pippin DA. Privileged structures: Applications in drug discovery. Comb. Chem. High T. Scr. 2004;7:473–493. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328544. doi:10.2174/1386207043328544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costantino L, Barlocco D. Privileged structures as leads in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:65–85. doi:10.2174/092986706775197999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duarte CD, Barreiro EJ, Fraga CAM. Privileged structures: a useful concept for the rational design of new lead drug candidates. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2007;7:1108–1119. doi: 10.2174/138955707782331722. doi:10.2174/138955707782331722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costantino L, Barlocco D. Privileged structures as leads in medicinal chemistry. Front. Med. Chem. 2010;5:381–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verma A, et al. Nitrogen-containing privileged structures and their solid phase combinatorial synthesis. Comb. Chem. High T. Scr. 2013;16:345–393. doi: 10.2174/1386207311316050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frankowski KJ, et al. Synthesis and receptor profiling of Stemona alkaloid analogues reveal a potent class of sigma ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:6727–6732. S6727/6721–S6727/6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016558108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016558108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilli RA, Rosso GB, de Oliveira M. d. C. F. The Stemona alkaloids. Alkaloids. 2005;62:77–173. doi: 10.1016/s1099-4831(05)62002-0. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(05)62002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilli RA, Rosso GB, de Oliveira M. d. C. F. The chemistry of Stemona alkaloids: An update. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1908–1937. doi: 10.1039/c005018k. doi:10.1039/C005018K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinreb SM. Studies on Total Synthesis of the Cylindricine/Fasicularin/Lepadiformine Family of Tricyclic Marine Alkaloids. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2531–2549. doi: 10.1021/cr050069v. doi:10.1021/cr050069v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gericke N, Viljoen AM. Sceletium—A review update. J. Ethnopharm. 2008;119:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.043. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez EG, Mendez-Galvez C, Cassels BK. Cytisine: a natural product lead for the development of drugs acting at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:555–567. doi: 10.1039/c2np00100d. doi:10.1039/c2np00100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daly JW. Nicotinic agonists, antagonists, and modulators from natural sources. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2005;25:513–552. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-3968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wrobleski A, Coombs TC, Huh CW, Li S-W, Aubé J. The Schmidt Reaction. Org. React. 2012;78:1–320. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng Y, Reddy DS, Hirt E, Aube J. Domino Reactions That Combine an Azido-Schmidt Ring Expansion with the Diels-Alder Reaction. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4993–4995. doi: 10.1021/ol047809r. doi:10.1021/ol047809r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gracias V, Frank KE, Milligan GL, Aubé J. Ring Expansion by in situ Tethering of Hydroxy Azides to Ketones: The Boyer Reaction. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16241–16252. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith BT, Wendt JA, Aube J. First Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (+)-Sparteine. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2577–2579. doi: 10.1021/ol026230v. doi:10.1021/ol026230v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer AM, Katz CE, Li S-W, Vander Velde D, Aube J. A Tandem Prins/Schmidt Reaction Approach to Marine Alkaloids: Formal and Total Syntheses of Lepadiformines A and C. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1244–1247. doi: 10.1021/ol100113r. doi:10.1021/ol100113r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenster E, et al. Three-Component Synthesis of 1,4-Diazepin-5-ones and the Construction of γ-Turn-like Peptidomimetic Libraries. J. Comb. Chem. 2008;10:230–234. doi: 10.1021/cc700174c. doi:10.1021/cc700174c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trost BM, Bogdanowicz MJ. New synthetic reactions. X. Versatile cyclobutanone (spiroannelation) and γ-butyrolactone (lactone annelation) synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:5321–5334. doi:10.1021/ja00797a037. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Danishefsky SJ. Cyclobutenone as a Highly Reactive Dienophile: Expanding Upon Diels-Alder Paradigms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11004–11005. doi: 10.1021/ja1056888. doi:10.1021/ja1056888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue L, Stahura F, Bajorath J. In: Chemoinformatics Vol. 275 Methods in Molecular Biology. Jürgen Bajorath., editor. Humana Press; 2004. pp. 279–289. Ch. 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopp F, Stratton CF, Akella LB, Tan DS. A diversity-oriented synthesis approach to macrocycles via oxidative ring expansion. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:358–365. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.911. doi:10.1038/nchembio.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauer WHB, Schwarz MK. Molecular Shape Diversity of Combinatorial Libraries: A Prerequisite for Broad Bioactivity. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 2003;43:987–1003. doi: 10.1021/ci025599w. doi:10.1021/ci025599w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veber DF, et al. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. doi:doi:10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauer RA, Wurst JM, Tan DS. Expanding the range of ‘druggable’ targets with natural product-based libraries: an academic perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010;14:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.