Significance

This study provides an understanding of how neurosteroids regulate the membrane expression of the α4 subunit-containing extrasynaptic GABAA receptor (GABAAR) subtypes that mediate tonic inhibition. This is significant because it defines an unexpected molecular mechanism by which neurosteroids produce long-lasting changes in the efficacy of GABAergic tonic inhibition. This is expected to lead to the development of pharmacological strategies that can control the number of GABAARs on the cell surface. These strategies hold the promise of restoring tonic inhibition in diseases that are associated with a reduced expression of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs by boosting the expression of extrasynaptic GABAARs to alleviate a broad range of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: PKC, tonic current, receptor insertion, current rundown

Abstract

Neurosteroids are synthesized within the brain and act as endogenous anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, and sedative agents, actions that are principally mediated via their ability to potentiate phasic and tonic inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs). Although neurosteroids are accepted allosteric modulators of GABAARs, here we reveal they exert sustained effects on GABAergic inhibition by selectively enhancing the trafficking of GABAARs that mediate tonic inhibition. We demonstrate that neurosteroids potentiate the protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of S443 within α4 subunits, a component of GABAAR subtypes that mediate tonic inhibition in many brain regions. This process enhances insertion of α4 subunit-containing GABAAR subtypes into the membrane, resulting in a selective and sustained elevation in the efficacy of tonic inhibition. Therefore, the ability of neurosteroids to modulate the phosphorylation and membrane insertion of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs may underlie the profound effects these endogenous signaling molecules have on neuronal excitability and behavior.

Neurosteroids are synthesized de novo in the brain from cholesterol, or steroid hormone precursors. Raising neurosteroid levels in the CNS causes anxiolysis, sedation/hypnosis, anticonvulsant action, and anesthesia and reduces depressive-like behaviors (1–3). Accordingly, dysregulation of neurosteroid signaling is associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, panic disorder, depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Neurosteroids exert the majority of their actions via potentiating the activity of γ-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAARs), which mediate the majority of fast synaptic inhibition in the adult brain. Accordingly, at low nanomolar concentrations they potentiate GABA-dependent currents, whereas at micromolar concentrations they directly activate GABAARs (4–8).

GABAARs are Cl−-preferring pentameric ligand-gated ion channels that assemble from eight families of subunits: α(1–6), β(1–3), γ(1–3), δ, ε, ө, π, and ρ(1–3) (9, 10). Receptor subtypes composed of α1–3βγ subunits largely mediate synaptic or phasic inhibition, whereas those constructed from α4–6β1–3, with or without γ/δ subunits, are principal determinants of tonic inhibition (11–13). Neurosteroids have been shown to bind GABAARs at an allosteric site distinct from that of GABA, benzodiazepines, or barbiturates (9, 14). Hosie et al. identified residues located within the transmembrane domain of GABAAR α and β subunits that are critical for the direct activation (α1–6; Threonine 236, β1–3; Tyrosine 284) and allosteric potentiation (α1–6 Asparagine 407, and α1–6 Glutamine 246) of neurosteroids (15–17). Accordingly, mutation of glutamine 241 (Q241) within the α1–6 subunits prevents allosteric potentiation of GABAAR composed of αβγ and αβδ subunits by neurosteroids (15, 16).

In addition to modulating channel gating, neurosteroids exert potent effects on the expression levels of GABAARs (1, 18–20). Moreover, in the hippocampus, prolonged exposure to physiological concentrations of neurosteroids has been shown to enhance the tonic conductance mediated by extrasynaptic GABAARs containing the α4/δ subunits, while having little effect on the phasic conductance mediated by synaptic GABAARs (6, 21). However, the molecular mechanisms by which neurosteroids regulate GABAAR expression levels remain unknown.

Here, we reveal that neurosteroids act to increase the PKC-dependent phosphorylation of serine 443 (S443) within the intracellular domain of the α4 subunit. This process leads to increased insertion of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs into the plasma membrane and a selective enhancement of tonic inhibition. Thus, our experiments reveal a previously unidentified molecular mechanism by which neurosteroids exert sustained effects on GABAergic inhibition by selectively increasing α4-containing GABAARs in the membrane and therefore potentiate tonic inhibition.

Results

Neurosteroids Selectively Increase the Phosphorylation and Cell Surface Stability of Recombinant GABAARs Containing α4 Subunits.

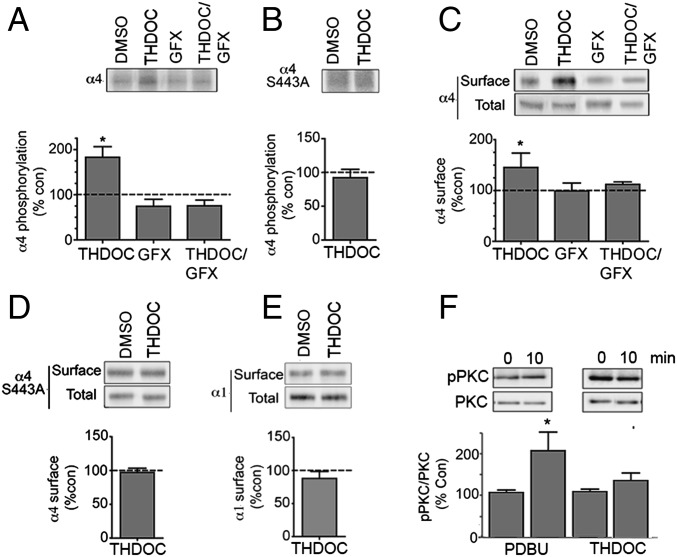

To further examine how neurosteroids modulate GABAergic inhibition, we tested their effects on the phosphorylation and membrane trafficking of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs that are the principle mediators of tonic inhibition in the dentate gyrus, and other regions of the forebrain (22, 23). As neuronal GABAARs exhibit extensive heterogeneity of structure, our first experiments focused on recombinant receptors composed of α4/β3 subunits expressed in HEK cells (24). The neurosteroid tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC; 100 nM) increased phosphorylation of the α4 subunit to 182.9 ± 23.1% of control (Fig. 1A; P = 0.0058), an effect prevented by the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (GFX) (Fig. 1A; 75.5 ± 12.5% of control, P = 0.095). PKC principally phosphorylates S443 within the intracellular domain of the α4 subunit (24), and mutation of this residue to an alanine (S443A) abolishes THDOC-induced phosphorylation (Fig. 1B; 92.3 ± 12.4% of control, P = 0.298).

Fig. 1.

Neurosteroids regulate the phosphorylation and cell surface expression of recombinant GABAARs containing α4 subunits. (A) HEK cells expressing α4β3 receptors were labeled with 1 mCi/mL 32P-orthosphosphoric acid and treated for 10 min with DMSO (control), 100 nM THDOC, or 20 μM GFX/100 nM THDOC. Phosphorylation of α4 was measured using immunoprecipitation with subunit-specific antibodies and data normalized to vehicle-treated samples. (B) The effects of 100 nM THDOC on the phosphorylation of receptors composed of α4S443A subunits were measured as outlined above. (C) Cells expressing α4β3 subunits were treated for 10 min with DMSO (control), 100 nM THDOC, or 20 μM GFX/100 nM THDOC and labeled with NHS-biotin. The resulting cell surface and total fractions were then immunoblotted with α4 subunit antibodies. The ratio of cell surface to total α4 subunit immunoreactivity was determined and normalized to vehicle-treated control (dotted line; 100%). (D) The effects of 100 nM THDOC on the cell surface accumulation of receptors composed of α4(S443A) and β3 subunits were measured as outlined above. (E) The effects of 100 nM THDOC on the cell surface accumulation of receptors composed of α1 and β3 subunits were measured as outlined above. (F) HEK cells were treated with 100 nM PDBU or 100 nM THDOC for 10 min and then immunoblotted with pT638 and a PKC antibody that recognizes the α, βI–II, and γ subtypes of PKC. The ratio of pT638/PKC immunorecativity was determined and normalized to levels seen at t = 0. *, significantly different to control in all panels (P < 0.05; n = 4–6).

In parallel with modulating phosphorylation, THDOC increased the cell surface expression levels of receptors containing α4 subunits to 145.3 ± 23.5% of control (Fig. 1C; P = 0.05), an effect prevented by GFX (Fig. 1C; 112.2 ± 4.9% of control, P = 0.06). In common with THDOC-induced phosphorylation, its effects on α4 subunit expression were prevented by the S443A mutation (Fig. 1D; 97.2 ± 6.2% of control, P = 0.341). We also assessed the ability of THDOC to modulate the cell surface accumulation of receptors containing α1 subunits that are principle mediators of phasic inhibition in the brain (12). In contrast to our results with GABAARs containing α4 subunits, THDOC did not significantly modify the cell surface levels of the α1 subunit when coexpressed with β3 (Fig. 1E; 88.0 ± 10.5% of control, P = 0.188).

The effects of THDOC on α4 subunit phosphorylation may reflect its ability to directly activate PKC. To test this, we examine the effects of THDOC on activity of classical PKC isoforms (α, βI–II, and γ) by measuring phosphorylation of T638, an accepted marker for kinase activity (25). Phorbol Di-butyrate (PDBU) increased PKC activity to 202 ± 45% of control (Fig. 1F; P = 0.032), whereas THDOC was without effect (Fig. 1F; 133 ± 69%, P = 0.267).

Neurosteroids Selectively Potentiate the Phosphorylation and Cell Surface Accumulation of α4 Subunit-Containing GABAARs in the Hippocampus.

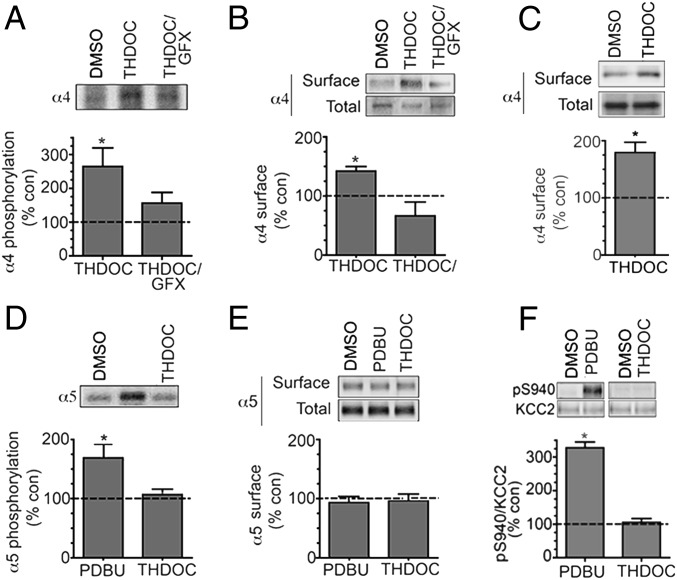

To assess the significance of our results using recombinant α4 subunits, we measured the effects of THDOC on the phosphorylation of this subunit in hippocampal slices prepared from 2- to 3-mo-old C57/Bl6 mice. A total of 100 nM THDOC enhanced phosphorylation of the α4 subunit to 264.4 ± 54.5% of control (Fig. 2A; P = 0.047), an effect that was blocked by GFX (Fig. 2A; 156.6 ± 31.5% of control, P = 0.0861). In parallel with this, THDOC increased the plasma membrane accumulation of the α4 subunit to 143.7 ± 12.4% of control (Fig. 2B; P = 0.0121), an effect prevented by GFX (Fig. 2B; 66.4 ± 23.5%, P = 0.1449). It is widely believed that in the dentate gyrus the majority of tonic inhibition is mediated by GABAARs composed of α4, β2/3, and δ subunits (6, 23). Thus, for comparison with our recombinant experiments, we assessed the effects of THDOC on cell surface levels of the α4 subunit in hippocampal slices from δ knockout mice (26). In the absence of the δ subunit, THDOC significantly increased the plasma membrane accumulation of the α4 subunit to 182.5 ± 24.5% of control (Fig. 2C; P = 0.014).

Fig. 2.

Neurosteroids selectively regulate the phosphorylation and cell surface expression of GABAARs containing α4 subunits in hippocampal slices. (A) We labeled 350 μm hippocampal slices from 8- to 12-wk-old mice with 1 mCi/mL 32P-orthosphosphoric acid and treated them for 10 min with DMSO (control), 100 nM THDOC, or 20 μM GFX/100 nM THDOC. Phosphorylation of α4 was measured using immunoprecipitation with subunit-specific antibodies and data normalized to vehicle-treated samples (dotted line; 100%). (B) Hippocampal slices were treated as above and subject to biotinylation. Cell surface and total fractions were then immunoblotted with α4 subunit antibodies. The ratio of cell surface to total α4 subunit immunoreactivity was determined and normalized to vehicle-treated controls. (C) Cell surface expression levels of the α4 subunit were determined in hippocampal slices from C57/Bl6 δ-KO mice treated for 10 min with DMSO (control) or 100 nM THDOC as detailed above. (D) Phosphorylation of the α5 subunit was measured in 32P-labeled hippocampal slices using immunoprecipitation with subunit-specific antibodies and data normalized to vehicle-treated samples. (E) Hippocampal slices were treated as above and subject to biotinylation. Cell surface and total fractions were then immunoblotted with α5 subunit antibodies. The ratio of cell surface to total α5 subunit immunoreactivity was determined and normalized to vehicle-treated controls. (F) Hippocampal slices were treated with the respective agents and then immunoblotted with pS940 and KCC2 antibodies. The ratio of pS940/KCC2 immunoreactivity was determined and normalized to vehicle-treated controls (dotted line; 100%).

To assess the specificity of THDOC’s action on the α4 subunit, we examined its effects on phosphorylation of the GABAAR α5 subunit, a component of receptor subtypes that mediate tonic inhibition in the CA1 and CA3 domains of the hippocampus (27). PDBU increased the phosphorylation of the α5 subunit to 167.6 ± 26.5% of control (Fig. 2D; P = 0.042), but THDOC did not (Fig. 2D; 104.64 ± 9.5% of control, P = 0.33). However, neither agent modified cell surface levels of the α5 subunit (Fig. 2D; 94.2 ± 4.2% and 96.39% of control, P = 0.296 and P = 0.312, respectively). The effects of THDOC on the phosphorylation of S940, a PKC substrate, within the structurally unrelated membrane protein, potassium-chloride cotransporter (KCC2), was analyzed (28). PDBU enhanced S940 phosphorylation to 301.4 ± 15.4% of control (P = 0.015), but THDOC was without effect (Fig. 2B; 95.5 ± 7.4% of control, P = 0.327).

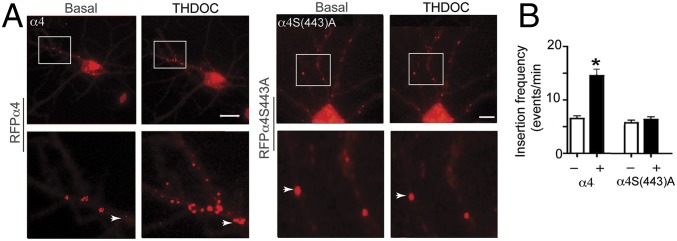

Neurosteroids Enhance the Membrane Insertion of GABAARs Dependent upon S443 in the α4 Subunit.

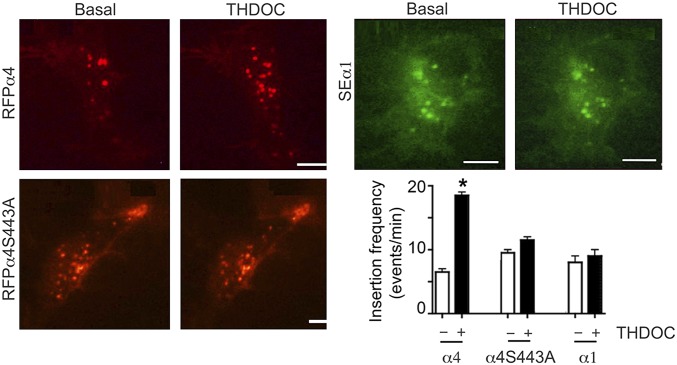

To directly visualize the effects of neurosteroids on GABAAR membrane trafficking, we used a α4 construct modified at its N terminus with red fluorescent protein (RFPα4) and the minimal binding sequence for α-bungarotoxin (Bgt) between amino acids 4 and 5 of the mature protein. Both of these modifications are neutral with regards to GABAAR assembly and function (24). The number of plasma membrane insertion events for RFPα4 subunit-containing receptors was then measured using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (29). TIRF microscopy was used to measure insertion frequency before and after incubation with 100 nM THDOC. Newly inserted RFPα4 subunits appeared as puncta on or very close to the membrane surface of HEK293 cells. Under basal conditions, the frequency of insertion for RFPα4 was 6.4 ± 1.2 events per minute. After 20-min incubation with THDOC, insertion increased to 18.5 ± 1.9 events per minute (Fig. 3; P = 0.003). In agreement with our biochemical studies, mutation of S443 prevented THDOC-dependent modulation of α4 subunit insertion (RFPα4S443A; Fig. 3; 8.5 ± 1.9 and 9.2 ± 2.3 at 0 and 20 min THDOC, respectively, P = 0.321). To determine if the effects of neurosteroids are dependent on vesicular-dependent membrane transport, we used botulinum neurotoxin A (BotA). This reagent prevented the effects of THDOC on the membrane insertion of RFPα4 (Fig. S1; basal 6.9 ± 1.4 and THDOC/BotA 4.6 ± 0.9 events per minute; P = 0.035). To assess if THDOC modifies the insertion of α1 subunit-containing GABAARs, we used a version of this protein modified between amino acids 4 and 5 by the insertion of super ecliptic pHluorin (SEα1) (30). The insertion rate for SEα1 was comparable under basal conditions and after THDOC treatment (Fig. 3; 8.1 ± 1.9 and 8.3 ± 2.3 events per minute, respectively; P = 0.217).

Fig. 3.

Neurosteroids modulate the membrane insertion of GABAARs dependent upon S443 in the α4 subunit. HEK cells expressing RFPα4β3, RFPα4(S443A)β3, or SEα1β3 receptors were imaged by TIRF for 5 min before (basal) and after 20-min incubation with 100 nM THDOC. These data were then used to determine the insertion frequency for each α subunit construct in the absence and presence of THDOC, as shown in the lower right panel. *, significantly different from control (P < 0.05; n = 5).

To control for our measurements on insertion, we examined if THDOC exerts any effects on the endocytosis of GABAARs. To do so, live cells expressing RFPα4/β3 subunits were labeled with Alexa Fluor488–Bgt to label surface RFPα4 subunits. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C, and the ratio of Alexa488/RFP fluorescence was determined over time. This revealed that the loss of Alexa488 staining over a time course of 20 min was equivalent for cells incubated in the absence and presence of THDOC (Fig. S2; P = 0.756).

To examine if THDOC exerts similar effects on the insertion of GABAARs in their native environment, we expressed RFPα4 in cultured hippocampal neurons using nucleofection. TIRF measurements were then made to analyze the insertion frequency for RFPα4 subunits under basal conditions and after incubation with THDOC. RFPα4 subunit insertion events were evident on the cell body and within neuronal processes. Under basal conditions, the frequency of insertion for RFPα4 subunits in hippocampal neurons was 7.1 ± 0.9 events per minute, which was increased to 14.5 ± 2.2 events per minute by THDOC (Fig. 4; P = 0.0032). Consistent with our experiments in HEK cells, the frequencies of insertion for RFPα4S443A were unaffected by THDOC (Fig. 4; 6.6 ± 0.5 and 6.8 ± 0.7 events per minute for basal and THDOC, respectively; P = 0.426).

Fig. 4.

Neurosteroids modulate the membrane insertion of the α4 subunit in hippocampal neurons. (A) The 10–15 Div hippocampal neurons expressing RFPα4 or RFPα4(S443A) subunits were subject to TIRF for 5 min before (basal) and 5 min after 20-min incubation at 37 °C with 100 nM THDOC. The images in the lower panels are enlargements of the boxed regions in the upper panels. (B) The total number of insertion events per minute was then calculated in the absence and presence of THDOC. *, significantly different from control (t test, P < 0.05; n = 5–7).

Neurosteroids Selectively Potentiate the Activity of GABAARs Incorporating α4 Subunits.

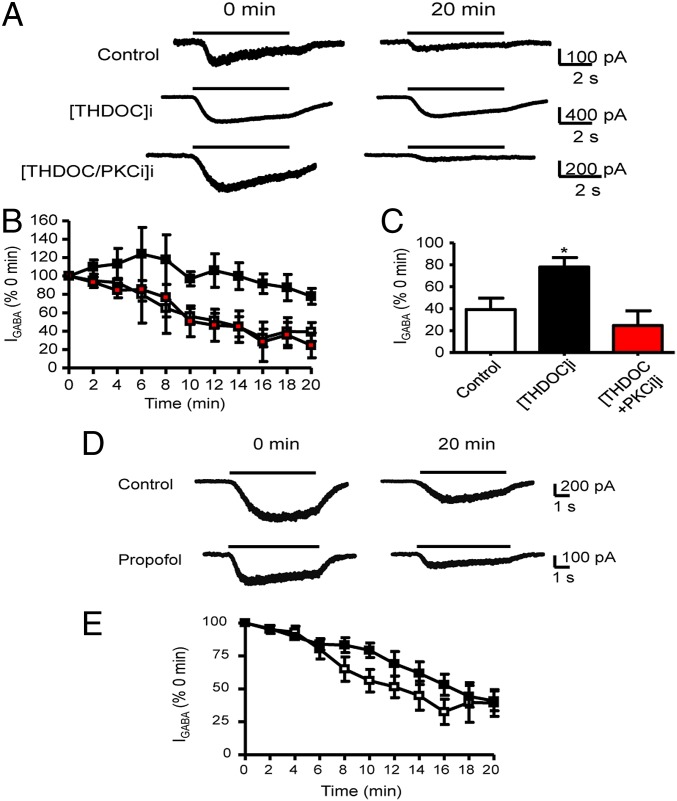

To address the significance of our biochemical findings, we assess the effects of neurosteroids applied to the inside of cells, via intracellular dialysis with the patch pipette. Internal application of neurosteroids has been established to have no effects on basal GABAAR function nor impacts on the ability of external applications of neurosteroids to allosterically modulate receptor function (31). Here we measured the effects of internally applied neurosteroids on the rundown of whole-cell GABA (IGABA) currents recorded from cells expressing receptors composed of α4β3 subunits. Current rundown is seen in all whole-cell recordings and for GABAARs is thought to reflect a loss in the activity/number of GABAARs (12, 13). At 20 min after the start of the experiment, IGABA for receptors composed of α4β3 subunits exhibited pronounced rundown to 39 ± 10% (n = 6) compared with the initial response (P = 0.021). Inclusion of 100 nM THDOC in the patch pipette significantly reduced this rundown to 78 ± 9% (n = 3) of the initial response (P = 0.025). Consistent with our biochemical studies, the effects of THDOC on IGABA were prevented via inclusion of PKC19–36 inhibitory peptide (Fig. 5 A–C). At 20 min after starting the experiment, IGABA was 25 ± 14% (n = 3) of the initial response in the presence of internal THDOC plus PKC19–36 inhibitory peptide (P = 0.43 compared with control rundown). The ability of internal THDOC to modulate IGABA is not a general property of GABAAR allosteric modulators because internal application of the general anesthetic and allosteric modulator, propofol, did not modify rundown (Fig. 5 D and E). In the presence of internal 3 μM propofol, IGABA at 20 min was 41 ± 8% (n = 3) of the initial response (P = 0.9 compared with control). The efficacy of THDOC to limit rundown of IGABA appeared to be specific for α4 subunit-containing GABAARs, as this agent did not modify rundown for receptors composed of α1β3 (control, 33 ± 14%, n = 4; THDOC, 41 ± 19%, n = 4; P = 0.75; Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

Internal THDOC prevents GABAA α4β3 receptor-mediated current rundown via a PKC-dependent process. (A) The 1 μM (∼EC50) GABA-activated currents (IGABA) recorded at 0 and 20 min after the start of the experiment (defined as t = 0 min and 100%). Whole-cell currents were recorded from HEK cells expressing α4β3 receptors in the presence of internally applied vehicle (DMSO) control (upper currents), internal 100 nM THDOC ([THDOC]i; middle currents), or internal THDOC plus 200 nM PKC19–36 inhibitor peptide ([THDOC/PKCi]i; lower currents). The black line above the current traces represents the application of GABA. (B) Time dependence relationship for (IGABA) recorded in the presence of either internally applied vehicle control (DMSO) (white square), 100 nM THDOC (black square), or 100 nM THDOC and 200 nM PKC19–36 inhibitor peptide (red square). *, significantly different from control DMSO and PKC inhibitor peptide (P = 0.025, n = 3–6). (C) Bar graph of the (IGABA) at t = 20 min compared with currents at t = 0 min for α4β3 receptors in control conditions (white bar) or in the presence of internal 100 nM THDOC (black bar) or internal THDOC plus PKC19–36 inhibitor peptide (red bar). (D) GABA-activated currents recorded from α4β3 receptors at 0 and 20 min after the start of the experiment either in the absence (control, upper currents) or presence of internal 3 μM propofol (lower currents). (E) The time dependence relationship for (IGABA) recorded in the presence of either internally applied vehicle control (white square) or Propofol (black square).

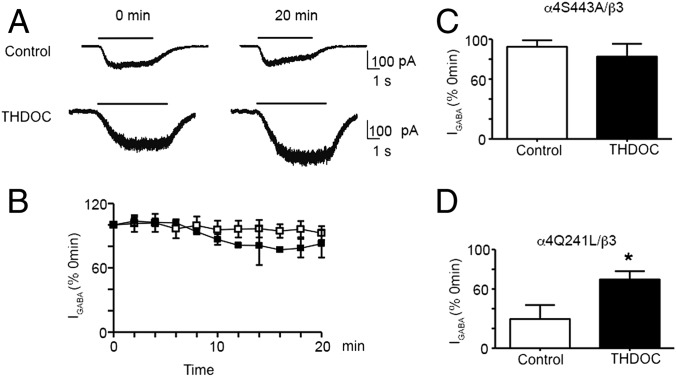

Neurosteroids Mediate Their Effects on IGABA via S443.

Our biochemical experiments suggest that the effects of THDOC on α4 subunit cell surface stability are dependent on S443. Thus, we tested the role that this residue plays in regulating the rundown of IGABA for α4 subunit-containing receptors. IGABA for receptors composed of α4(S443A)β3 exhibited minimal rundown that was insensitive to THDOC (Fig. 6 A–C; 92 ± 7%, n = 4 for control, P = 0.45, and 83 ± 13%, n = 3 for THDOC, P = 0.54). Published studies have identified a conserved residue within the receptor α subunit isoforms that is critical in regulating GABAAR allosteric potentiation by neurosteroids, glutamine 241 (Q241) in the case of the α4 subunit (15). To assess the ability of neurosteroids to modulate rundown, we mutated the respective residue in the α4 subunit to a leucine (α4Q241L). For α4(Q241L)β3 receptors, IGABA was reduced to 30 ± 14% (n = 4) at 20 min, and this rundown was decreased to 70 ± 8% (n = 3) in the presence of internal THDOC (Fig. 6D; P = 0.026). Likewise, THDOC increased the cell surface expression level of receptors containing the α4(Q241L) subunit to 145.4 ± 17% of control (Fig. S4; P = 0.021).

Fig. 6.

Prevention of α4β3 receptor-mediated current rundown by THDOC is dependent upon S443 in the α4 subunit but independent of THDOC-mediated allosteric modulation. (A) (IGABA) recorded at 0 and 20 min after the start of the experiment. Whole-cell currents were recorded from HEK293 cells expressing α4(S443A)β3 receptors in the presence of internally applied vehicle control (upper currents) or internal 100 nM THDOC ([THDOC]i; lower currents). The black line above the current traces represents the application of GABA. (B) Time dependence relationship for (IGABA) recorded in the presence of either internally applied vehicle control (white square) or 100 nM THDOC (black square). (C) Bar graph of the relative (IGABA) at t = 20 min compared with current at t = 0 min for α4(S443A)β3 receptors in control conditions (white bar) or perfused internally with 100 nM THDOC (black bar). (D) Bar graph of the relative (IGABA) at t = 20 min compared with current at t = 0 min for α4(Q241L)β3 receptors in control conditions (white bar) or perfused internally with 100 nM THDOC (black bar). *, significantly different from control (t test, P = 0.026; n = 3–6).

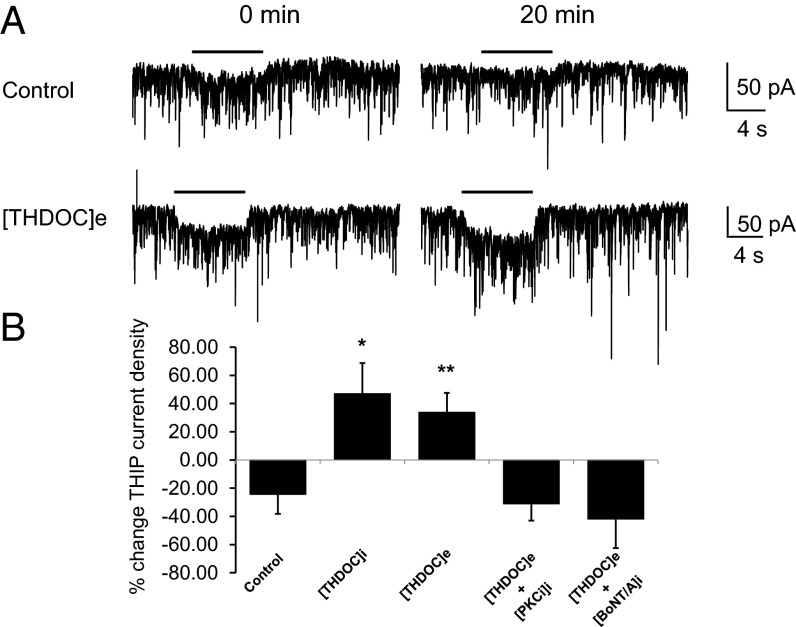

Neurosteroids Selectively Modulate Tonic Current in Hippocampal Neurons Dependent on PKC Activity and Vesicular-Dependent Membrane Trafficking.

The effects of internal application of neurosteroids on tonic current in 21–29 days in vitro (Div) hippocampal were determined. Neurons in these cultures express significant levels of the α4 subunit immunoreactivity, which is largely excluded from inhibitory synapses containing the inhibitory synaptic scaffold gephyrin (Fig. S5). To measure the effects of neurosteroids on α4-mediated currents, we used the receptor agonist 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol (THIP), which at 1 μM shows selectivity for GABAAR subtypes containing α4/δ subunits (32). Under control conditions, ITHIP at 20 min was reduced by 24.4 ± 14% (n = 11) of the initial response (Fig. 7 A and B). In contrast, when the neurons were incubated for 10 min with external THDOC (100 nM), ITHIP was significantly increased by 33.9 ± 13.7% (n = 9) relative to control (P = 0.008). In the presence of internal THDOC, ITHIP was increased by 47.1 ± 21.7% (n = 11, P = 0.01; Fig. 7 A and B). To assess if the effects of THDOC were dependent upon PKC activity, we used internal solutions supplemented with PKC19–36 inhibitory peptide. Under these conditions, ITHIP was reduced by 31.2 ± 12% (n = 5) at 20 min (P = 0.014). Likewise, the ability of external THDOC to modulate ITHIP was ablated via internal exposure to 1 μg/μL BotA (Fig. 7B) [ITHIP was reduced by 41.9 ± 20.6% (n = 5) of the initial response; P = 0.010].

Fig. 7.

THDOC selectively enhances tonic current in hippocampal neurons. (A) THIP-activated currents recorded at 0 and 20 min after the start of the experiment. Whole-cell currents were recorded from 21–29 Div rat hippocampal neurons in the presence of internally applied vehicle control (upper currents) or following a 10-min exposure to extracellular 100 nM THDOC ([THDOC]e; lower currents). The black line above the current traces represents the application of THIP. (B) Bar graph of the percent change in THIP-activated currents between t = 0 and t = 20 min for hippocampal neurons in control conditions, internal 100 nM THDOC ([THDOC]i), and following a 10-min exposure to extracellular 100 nM THDOC ([THDOC]e) (* and **, significantly different from control, P = 0.01, and P = 0.008, respectively; n = 9–11). The increase in THIP current observed with [THDOC]e was inhibited with the inclusion of internal 200 nM PKC19–36 inhibitor peptide ([PKCi]i) or 1 μg/μL BotA ([BotA]i) (both P = 0.01 compared with [THDOC]e alone; n = 5).

Discussion

The ability of neurosteroids to allosterically modulate GABAAR gating is largely dependent upon amino acid residues that are conserved within all receptor α subunit isoforms (15, 16). In addition to allosteric modulation, neurosteroids have also been shown to exert potent actions on GABAAR expression levels in many brain regions (1, 33, 34). To examine how neurosteroids regulate GABAAR expression, we have assessed their effects on the membrane trafficking of GABAARs containing α4 subunits. Receptor subtypes containing α4/δ subunits mediate tonic inhibition in the dentate gyrus and show preferential sensitivity to neurosteroid regulation, compared with receptor subtypes that mediate phasic inhibition in this brain region, and moreover neurosteroids have been suggested to exert long-term effects on neuronal excitation by dynamically regulating the expression levels of extrasynaptic GABAARs (35, 36).

Our initial studies examined the effects of THDOC on the membrane trafficking of recombinant GABAARs. THDOC enhanced the phosphorylation of the α4 subunit and its cell surface accumulation, effects that could be abolished by inhibiting PKC activity. Consistent with this change in the phosphorylation and surface expression, mutation of S443, the principle site of PKC phosphorylation in the α4 subunit, blocked the ability of THDOC to enhance both α4 subunit phosphorylation and cell surface expression levels (24). In parallel with this, THDOC increased the phosphorylation of α4 subunit-containing receptors dependent upon PKC activity in hippocampal slices. Significantly, THDOC did not modify the PKC-dependent phosphorylation of the GABAAR α5 subunit, or KCC2, further demonstrating the specificity of the effects on this reagent for receptors containing α4 subunits and indicating the lack of direct activation of PKC. The specificity of substrate phosphorylation is mediated by the precise targeting of kinase and phosphatase activities to the appropriate substrates, and accordingly, the α, βII, δ, and ε isoforms of PKC, together with the receptor for activated C-kinase (RACK-1), are intimately associated with GABAARs (37–41). Therefore, THDOC may act to increase the recruitment or activity of PKC isoforms associated with α4 subunit-containing GABAARs to enhance S443 phosphorylation and hence promote surface expression.

In addition to promoting phosphorylation of S443, THDOC enhanced the cell surface accumulation of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs, with minimal effects on those assembled from the α1 subunit. The effects on cell surface accumulation in common with the effects on phosphorylation were abrogated via inhibiting PKC activity, or via mutation of S443. α4 subunit-containing GABAARs are the principal mediators of tonic current in the dentate gyrus, and consistent with our recombinant experiments, THDOC increases the cell surface stability of the α4 subunit in hippocampal slices. Significantly, THDOC did not modify the cell surface levels of the α5 subunit that mediate tonic inhibition in hippocampal CA1/3 regions (11, 27).

To further examine the mechanism by which neurosteroids potentiate GABAAR cell surface stability, we examined their effects on the insertion of fluorescent GABAARs into the plasma membrane using TIRF microscopy. In both expression systems and neurons, THDOC increased the insertion of α4 subunits containing receptors into the plasma membrane without modifying their endocytosis, a process that was ablated by inhibiting vesicular-dependent membrane trafficking, or via mutation of S443. In contrast, THDOC had minimal effects on the membrane insertion of GABAARs containing α1 subunits. Thus, our biochemical and imaging studies suggest that THDOC acts to promote the membrane insertion of GABAARs via a PKC-dependent mechanism dependent upon S443 in the α4 subunit.

To assess if this putative mechanism has any effects on GABAAR function, we assessed the effects of internally applied neurosteroids on the rundown of whole-cell GABA-induced currents. This route of application was chosen as it allows the effects of neurosteroids on GABAAR trafficking to be distinguished from their accepted actions as allosteric modulators (31). Internal application of THDOC at physiological concentrations almost abrogated the rundown in the magnitude of IGABA over time for GABAARs composed of α4β3, an effect not replicated by internal application of propofol, a structurally unrelated GABAAR-positive allosteric modulator. Consistent with our measurements on α4 subunit phosphorylation and trafficking, the ability of THDOC to limit rundown of IGABA was prevented via coapplication of the selective PKC inhibitor peptide of PKC18–36, or via mutation of S443. The ability of neurosteroids to modulate rundown was also found to be specific for the α4 subunit, as THDOC did not prevent rundown for receptors containing α1 subunits. The ability of neurosteroids to act as allosteric potentiators of GABAAR activity is critically dependent upon amino acid residues that are conserved within the intracellular domains of receptor α1–6 subunits, Q241 in the case of α4 (15). However, mutation of this residue had minimal effects on the ability of THDOC to regulate the effects of internal THDOC on the rundown of IGABA. Thus, neurosteroids exert their effects as allosteric modulators and regulators of GABAAR membrane trafficking via distinct mechanisms.

Finally, we assessed the effects of persistent exposure to neurosteroids on the efficacy of GABAergic inhibition in mature cultures of hippocampal neurons (>21 Div), which express a plethora of endogenous GABAAR subtypes, including those assembled from α4 subunits (42, 43). To selectively test the effects on neurosteroids, we used low concentrations of the agonist THIP that shows selectivity for α4/δ subunit-containing receptors. THIP-induced currents exhibited a reduction in current amplitude over 20 min, which could be abrogated by either internal or a 10-min external application of THDOC. Consistent with our biochemical and imaging studies, the ability of THDOC to modulate ITHIP was prevented by internal application of PKC18–36 or via inhibition of vesicular-dependent membrane trafficking by internal application of BotA.

In summary, our results have revealed an as-yet-unappreciated “metabotropic” signaling mechanism for neurosteroids, by which they exert sustained effects on tonic inhibition by selectively modulating the phospho-dependent membrane insertion of α4 subunit-containing GABAARs.

Materials and Methods

More detailed information on the materials and methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Antibodies and Expression Constructs.

Polyclonal rabbit anti-α4 antibodies were provided by Verena Tretter and Werner Sieghart (Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria). Methods used were as previously described (24).

Cell Culture, Metabolic Labeling, and Immunoprecipitation.

Cultures and slices were labeled with [32P]orthophosphoric acid followed by immunoprecipitation with α4 antibodies (24).

Biotinylation.

Neurons were biotinylated as described previously (43).

Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology.

HEK293 cells and hippocampal neurons were used as previously described (24, 43).

Data Acquisition and Analysis.

For all experiments, data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student t test, where P < 0.05 is considered significant.

TIRF Microscopy.

HEK cells or hippocampal neurons expressing fluorescent GABAAR subunits were subject to live TIRF imaging using a Nikon Eclipse Ti Inverted TIRF Microscope (Nikon Instruments) at 32 °C. For more details, see SI Materials and Methods and Results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Simons Foundation Grant 206026 (to S.J.M.); National Institutes of Health (NIH)–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants NS051195, NS056359, and NS081735 (to S.J.M.); and NIH–National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH097446 (to P.A.D. and S.J.M.). M.T. is the recipient of a National Scientist Development Grant (09SDG2260557) from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1403285111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: Endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(7):565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul SM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J. 1992;6(6):2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Moore PH, Jr, Paul SM. Stress-induced elevations of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-active steroids in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(10):4553–4557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawley JN, Glowa JR, Majewska MD, Paul SM. Anxiolytic activity of an endogenous adrenal steroid. Brain Res. 1986;398(2):382–385. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belelli D, Herd MB. The contraceptive agent Provera enhances GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission in the rat hippocampus: Evidence for endogenous neurosteroids? J Neurosci. 2003;23(31):10013–10020. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10013.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I. Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):14439–14444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belelli D, Casula A, Ling A, Lambert JJ. The influence of subunit composition on the interaction of neurosteroids with GABA(A) receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43(4):651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majewska MD, Harrison NL, Schwartz RD, Barker JL, Paul SM. Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science. 1986;232(4753):1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.2422758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudolph U, Möhler H. Analysis of GABAA receptor function and dissection of the pharmacology of benzodiazepines and general anesthetics through mouse genetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:475–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudolph U, Möhler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABAA receptor subtype functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickley SG, Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: Their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron. 2012;73(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luscher B, Fuchs T, Kilpatrick CL. GABAA receptor trafficking-mediated plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Neuron. 2011;70(3):385–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob TC, Moss SJ, Jurd R. GABA(A) receptor trafficking and its role in the dynamic modulation of neuronal inhibition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(5):331–343. doi: 10.1038/nrn2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen RW, Chang CS, Li G, Hanchar HJ, Wallner M. Fishing for allosteric sites on GABA(A) receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(8):1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosie AM, Clarke L, da Silva H, Smart TG. Conserved site for neurosteroid modulation of GABA A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444(7118):486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, Smart TG. Neurosteroid binding sites on GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116(1):7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brussaard AB, Wossink J, Lodder JC, Kits KS. Progesterone-metabolite prevents protein kinase C-dependent modulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors in oxytocin neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(7):3625–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050424697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maguire JL, Stell BM, Rafizadeh M, Mody I. Ovarian cycle-linked changes in GABA(A) receptors mediating tonic inhibition alter seizure susceptibility and anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):797–804. doi: 10.1038/nn1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maguire J, Mody I. Neurosteroid synthesis-mediated regulation of GABA(A) receptors: Relevance to the ovarian cycle and stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2155–2162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4945-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(3):215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yee BK, et al. GABA receptors containing the alpha5 subunit mediate the trace effect in aversive and appetitive conditioning and extinction of conditioned fear. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(7):1928–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra D, et al. GABAA receptor alpha 4 subunits mediate extrasynaptic inhibition in thalamus and dentate gyrus and the action of gaboxadol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(41):15230–15235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramian AM, et al. Protein kinase C phosphorylation regulates membrane insertion of GABAA receptor subtypes that mediate tonic inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(53):41795–41805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker PJ, Murray-Rust J. PKC at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 2):131–132. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mihalek RM, et al. Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in gamma-aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(22):12905–12910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABA(A) receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28(6):1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HH, Deeb TZ, Walker JA, Davies PA, Moss SJ. NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(6):736–743. doi: 10.1038/nn.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trache A, Meininger GA. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2008;Chapter 2:1–, 22. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc02a02s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob TC, et al. Benzodiazepine treatment induces subtype-specific changes in GABA(A) receptor trafficking and decreases synaptic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(45):18595–18600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert JJ, Peters JA, Sturgess NC, Hales TG. Steroid modulation of the GABAA receptor complex: Electrophysiological studies. Ciba Found Symp. 1990;153:56–71, discussion 71–82. doi: 10.1002/9780470513989.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia F, et al. An extrasynaptic GABAA receptor mediates tonic inhibition in thalamic VB neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(6):4491–4501. doi: 10.1152/jn.00421.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulinello M, Gong QH, Li X, Smith SS. Short-term exposure to a neuroactive steroid increases alpha4 GABA(A) receptor subunit levels in association with increased anxiety in the female rat. Brain Res. 2001;910(1-2):55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02565-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu FC, Waldeck R, Faber DS, Smith SS. Neurosteroid effects on GABAergic synaptic plasticity in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89(4):1929–1940. doi: 10.1152/jn.00780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert JJ, Cooper MA, Simmons RD, Weir CJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroids: Endogenous allosteric modulators of GABA(A) receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S48–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harney SC, Frenguelli BG, Lambert JJ. Phosphorylation influences neurosteroid modulation of synaptic GABAA receptors in rat CA1 and dentate gyrus neurones. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45(6):873–883. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandon NJ, et al. Subunit-specific association of protein kinase C and the receptor for activated C kinase with GABA type A receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19(21):9228–9234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandon NJ, Jovanovic JN, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Receptor for activated C kinase-1 facilitates protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation and functional modulation of GABA(A) receptors with the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6353–6361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06353.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodge CW, et al. Decreased anxiety-like behavior, reduced stress hormones, and neurosteroid supersensitivity in mice lacking protein kinase Cepsilon. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(7):1003–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI15903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qi ZH, et al. Protein kinase C epsilon regulates gamma-aminobutyrate type A receptor sensitivity to ethanol and benzodiazepines through phosphorylation of gamma2 subunits. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(45):33052–33063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chou WH, et al. GABAA receptor trafficking is regulated by protein kinase C(epsilon) and the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor. J Neurosci. 2010;30(42):13955–13965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0270-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saliba RS, Kretschmannova K, Moss SJ. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of GABAA receptors regulates receptor insertion and tonic current. EMBO J. 2012;31(13):2937–2951. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.