Significance

Cooperation among humans depends upon the willingness of others to take costly action to enforce the social norm to cooperate. Such behavior is often coined third-party punishment. Here we show that third-party punishment is already effective as means to increase cooperation in children. Most importantly, we identify why this is the case. First, children expect (mistakenly) third parties to punish quite often and therefore they become more cooperative. Second, the presence of third parties lets children become (rightfully) more optimistic about the cooperation levels of the interaction partner in a simple prisoner’s dilemma game. As a reaction to more optimistic expectations, children cooperate more themselves. The experiment has been run with about 1,100 children aged 7 to 11 y.

Abstract

The human ability to establish cooperation, even in large groups of genetically unrelated strangers, depends upon the enforcement of cooperation norms. Third-party punishment is one important factor to explain high levels of cooperation among humans, although it is still somewhat disputed whether other animal species also use this mechanism for promoting cooperation. We study the effectiveness of third-party punishment to increase children’s cooperative behavior in a large-scale cooperation game. Based on an experiment with 1,120 children, aged 7 to 11 y, we find that the threat of third-party punishment more than doubles cooperation rates, despite the fact that children are rarely willing to execute costly punishment. We can show that the higher cooperation levels with third-party punishment are driven by two components. First, cooperation is a rational (expected payoff-maximizing) response to incorrect beliefs about the punishment behavior of third parties. Second, cooperation is a conditionally cooperative reaction to correct beliefs that third party punishment will increase a partner’s level of cooperation.

Human cooperation rates among genetically unrelated strangers in large groups are unusually high and exceed cooperation among all other animal species by far (1, 2). As early as in childhood, humans begin to conform to cooperative social norms (3), which raises the question of how such social norms are enforced because norm enforcement may explain why humans cooperate more than other animals. Although in repeated interactions reciprocity (4, 5) may account for the higher cooperation rates—given that, unlike chimpanzees, humans become reciprocal already in early childhood (6)—in nonrepeated (i.e., one-shot) settings a different mechanism must be at work (7). In fact, a growing body of literature suggests that the punishment of defectors is key to trigger and sustain cooperation in such contexts (7–11).

Punishment can take on the form of second-party punishment, where those who are the victims of defection can punish norm-violators (7, 12–18), or third-party punishment, where unaffected bystanders can execute sanctions against norm-violators, even though the bystanders are not materially affected by a norm violation (8, 19–29). Both humans and other animals use second-party sanctioning to promote cooperation (30, 31). However, although humans also engage in third-party punishment to increase cooperation rates, the evidence of third-party-punishment among nonhuman primates is mixed. [To date, it is unclear whether humans execute costly punishment (i) because they view defection as a violation of a broadly recognized group norm or (ii) because of a personal aversion to defection.] Whereas some research (32) suggests the existence of third-party punishment among nonhuman primates in the form of third-party policing (which refers to impartial interventions to control conflicts between conspecifics), others argue that impartial interventions in conflict situations are unlikely to qualify as third-party punishment, but rather are motivated by selfishness that yield cooperation only as a by-product (33). Thus, the deliberate punishment of defectors by third parties is a likely candidate to explain high cooperation rates in humans.

In this report, we study the ontogeny of cooperation and third-party punishment during childhood, focusing on the questions whether third parties increase cooperation rates already in children and, if they do, for which reasons. So far, the experimental literature has documented positive effects of third-party punishment on human cooperation exclusively for adult (typically student) populations (26–29). Because cooperation norms become internalized much earlier, already in childhood (3, 34), we consider it important to study how norm enforcement works in childhood. In their recent paper on the ontogeny of cooperative behavior (unrelated to norm enforcement through punishment), House et al. conclude that future research should examine “institutions that influence cooperative behavior and how their acquisition and application shapes children’s behavior across development” (3). We work in this direction by studying the effects of punishment institutions on the cooperative behavior of children.

We are particularly interested in whether children become more cooperative when a third party (of the same age) may punish them. If so, we try to disentangle the reasons for such a behavioral response by examining whether children become more cooperative because they are afraid of getting punished, or because they expect the partner in the cooperation game to cooperate in the presence of a third party, in which case third-party punishment works through the channel of conditional cooperation (35–37). Studying the behavior of children, as players in a cooperation game or as third parties, allows determining whether norm enforcement through third-party punishment works already at a young age (3, 38). This determination is of particular interest because potential third-party intervention is important among peers in school [for example, punishment threats of peers toward free-riders in cooperative learning environments to foster student’s commitment (39)], but it is unclear to date whether it shifts expectations about others’ behavior or whether the third-party punishment itself promotes norm enforcement.

The experiment was run in the city of Merano, Italy, with more than 1,100 primary school children, aged 7 to 11 y. We chose these age cohorts because: (i) important behavioral and economically relevant traits evolve during this period of life (40); (ii) peer interactions in primary school classes prepare children for their adult roles, teaching each other values and attitudes, such as cooperation (41, 42); and (iii) middle childhood (starting from around age 6) may be when children begin to conform to cooperative social norms (3). A necessary prerequisite for strategic interaction experiments to provide reliable results is that participants can understand them and, in our case, have developed the ability to take another person’s perspective. In contrast to nonhuman primates, like chimpanzees who “do not have a full-blown human-like theory of mind” (43), both conditions are entirely met in humans in the age cohorts considered in this report (3, 43–46). The participating children represent 86% of all primary school children in grades two to five in this city of 38,000 inhabitants.

Following previous literature on adults (26), we let our subjects play a one-shot, simultaneous prisoner’s dilemma (PD) game as a baseline (see Fig. 1 for an illustration of the game and Methods and the Supporting Information for details). Mutual cooperation yields the Pareto-efficient outcome of [4,4]. However, both players have a dominant strategy to defect, leading to the inefficient Nash-equilibrium of [2,2].

Fig. 1.

In the PD, players can either cooperate (C) or defect (D). Although mutual cooperation yields the socially optimal outcome of four tokens per player, each subject has an incentive to defect as a dominant strategy. Defection of both players is the Nash equilibrium of the game, yielding a payoff of two for each player. The first (second) number in each cell indicates player 1’s (player 2’s) payoff.

For the study, 554 children played this two-player game in a control treatment (CTR) without any third party. Matching was random and anonymous and pairs were always formed from the same age cohort. After having played the game once (but before being informed about the choice of their partner in the PD), these children were asked to act as third parties for another set of children. Children did not know about this additional task before completing play in the PD.

A different set of 566 children was assigned to a third-party punishment treatment (TPP). Children in the TPP were randomly and anonymously paired (within their age cohort) and then played the PD once. Each child in a pair of the TPP was assigned one child from the CTR as the third party, and children in the TPP were aware of this before making decisions. Of course, the children were not informed about the third-party’s decision before choosing to cooperate or defect. The third party (the child in the CTR) had to decide whether to invest a token to punish the assigned child (in the TPP) in case this child would defect in the PD. [Although both altruistic and spiteful punishment (i.e. the punishment of defectors and cooperators) is usually permitted in experiments with adults (26), we restricted our participants’ action space to altruistic punishment, because we are primarily interested in the enforcement of a social norm to cooperate and not whether children are willing to punish cooperative acts.] As a consequence of punishment, the child in the TPP lost all gains from the PD experiment if it had defected. If the child in the TPP had cooperated, or if the third party had not invested its token, then the third party kept the token, which could be exchanged into a reward. [We chose this binary punishment technology to assure comprehension. Although adults who act as third parties in such games are usually asked to choose the number of tokens to be invested into punishment (26, 29), we kept the design as simple as possible and thus only allowed for a binary decision.]

After having made their own decisions, we asked children about their beliefs. Both in the CTR and in the TPP treatment they were asked whether they expected the partner in their pair to cooperate. In the TPP they were additionally asked whether they expected the third party to punish defection. Correct guesses were rewarded with one token. All tokens earned in the experiment could be exchanged into presents 3 mo after the experiment (see Methods for an explanation of the procedure). By asking children in the TPP both about the expected punishment and the expected cooperation of their partner, we could check whether they cooperated to avoid punishment or because they expected the partner to cooperate as well.

Results

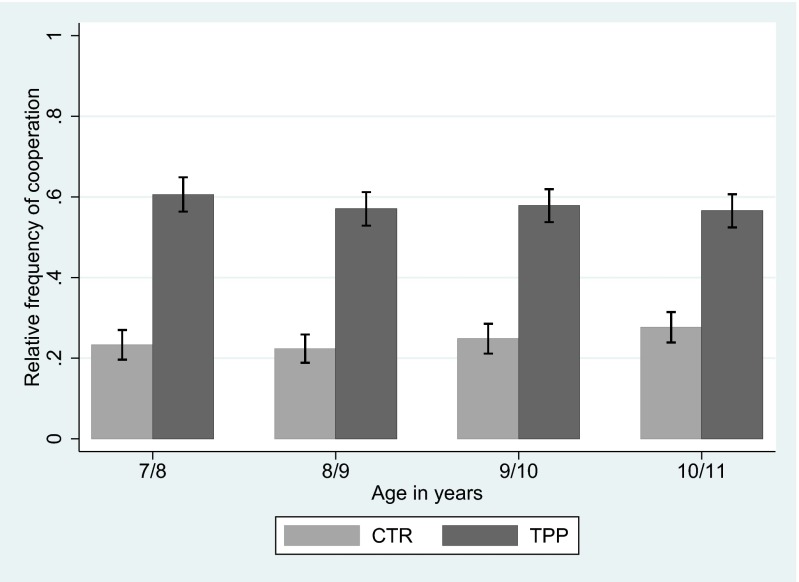

Fig. 2 shows cooperation rates across the four age cohorts for players in the CTR and in the TPP. Overall, we found that 58% of players cooperated in the one-shot PD in the TPP, but only 25% did so in the CTR (P = 0.000 overall and in each age group separately, χ2 tests). This finding means that the presence of a third party with an opportunity to punish defectors more than doubles cooperation rates. Looking at cooperation rates across age cohorts, we found no significant age effects within any treatment (P = 0.339 in the CTR and P = 0.552 in the TPP, Cuzick’s Wilcoxon-type test for trend).

Fig. 2.

Average cooperation rates by age and treatment (n = 554 in the CTR and n = 566 in the TPP). Error bars, mean ± SEM.

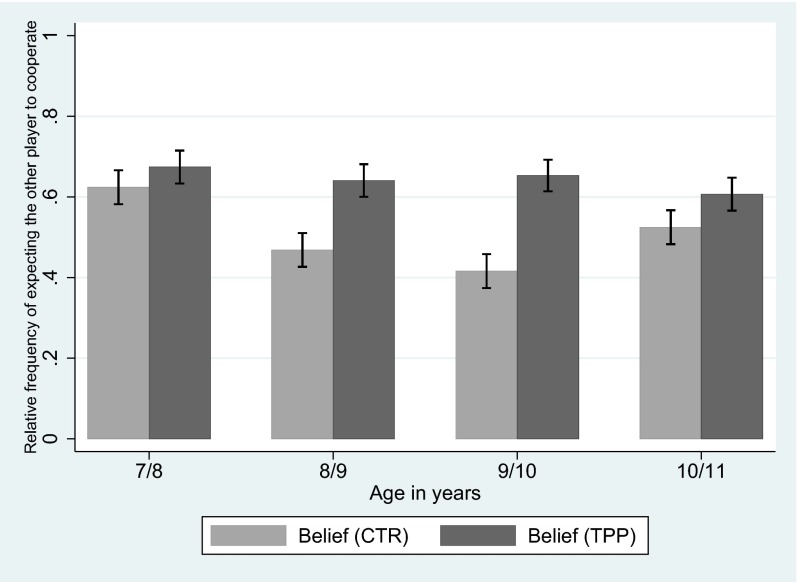

Fig. 3 illustrates players’ beliefs about their partner’s likelihood of cooperation. We found that beliefs significantly differed across treatments: 64% of subjects in the TPP, but only 51% in the CTR believe that their partner will cooperate (P = 0.000 across all age groups, χ2-test). This finding means that subjects anticipated that the presence of third parties would have an impact on the partner’s willingness to cooperate. In the TPP, in all four age cohorts the expected likelihood of cooperation matches the actual rate of cooperation fairly closely. Comparing the dark gray bars across Figs. 2 and 3 does not yield significant differences in any age cohort (P = 0.16 for 7/8 y; P = 0.16 for 8/9 y; P = 0.09 for 9/10 y; P = 0.42 for 10/11 y; McNemar’s tests). However, in the CTR all four age cohorts are too optimistic, because expected cooperation rates are always significantly higher than actual cooperation rates (see the light gray bars in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3; P < 0.01 in each cohort; McNemar’s tests). This latter result suggests an intention to free-ride on the (expected) contributions of partners, which implies a willingness to accept advantageous inequality (47, 48). As soon as a third party is present (in the TPP), however, expectations and actual behavior with respect to cooperation get well calibrated. This effect can explain why (potential) third-party punishment increases cooperation rates if subjects are conditional cooperators (35–37). For someone who conditions the level of cooperation on the interaction partner’s willingness to cooperate, third-party punishment shifts the expectations upwards, and hence triggers more cooperation, even in the absence of actual punishment. In fact, Fig. S1 shows that the average expectations of conditional cooperators (that is, subjects whose belief about the cooperative behavior of the partner is aligned with their own decision) are significantly higher in the TPP than in the CTR (P = 0.000 in each cohort; χ2 tests).

Fig. 3.

Average expectation of cooperative behavior of the partner by age and treatment (n = 554 in the CTR and n = 566 in the TPP). Error bars, mean ± SEM.

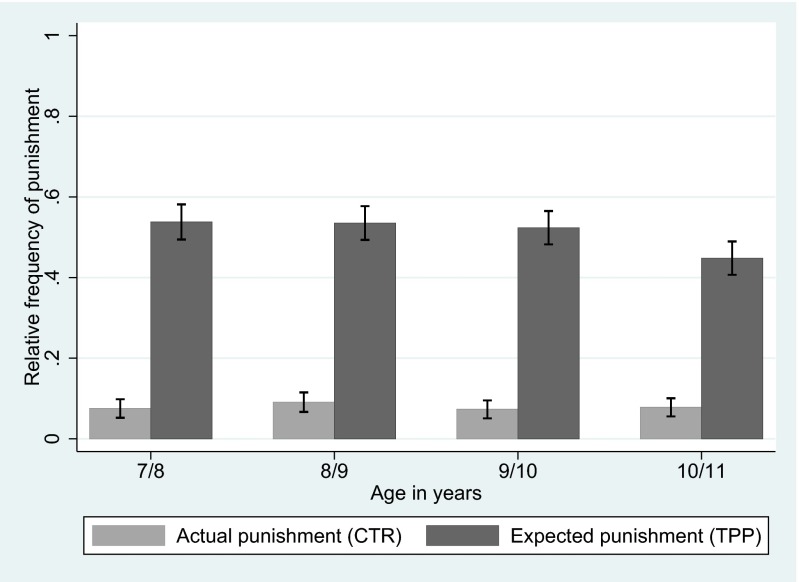

Fig. 4 juxtaposes actual and expected punishment rates. It turns out that third parties used the punishment option very rarely, overall in less than 10% of cases. [One possible reason for the low incidence of punishment rates could be the use of the strategy method to decide upon punishment. Third parties had to make decisions conditional on the player in the PD game choosing defection. This factor may leave the third party in an emotionally “cold” state, whereas choosing punishment after having seen the player defect in the PD game may create an emotionally “hot” state and then trigger more punishment. A recent survey comparing the strategy method with the latter type of direct-response method has failed to find a systematic behavioral impact of the strategy method, however (49). In their study on third-party punishment with adults, Fehr and Fischbacher (26) also used the strategy method for eliciting the decisions of third-party observers and found between 21% and 50% punishment rates (depending on the decision of the interaction partner in the PD). Our somewhat smaller punishment rates are compatible with the finding that children’s behavior is typically closer to payoff-maximization (which predicts no punishment) than adult behavior (50).] Players in the TPP expect third parties to punish in 51% of cases on average, however. The difference is highly significant throughout (P = 0.000 in each age cohort; χ2 tests), indicating a strong mismatch between beliefs and actual punishment behavior. A similar mismatch, albeit of smaller size, has been found in previous studies of third-party punishment when subjects share a pie very unevenly in a simple allocation task (26). Hence, the mismatch is not an artifact of our design or subject pool. [One might also argue that the mismatch between beliefs about the behavior of third parties and actual punishment rates is because of the difficulty of children playing the PD game to put themselves into the role of the third party and take her perspective. However, psychological studies on the development of Theory of Mind (44, 51) show that normally developing children are able to differentiate the other’s view from their own one by the age of 4 to 6 y, and then take the perspectives of other persons into account.] Moreover, the fact that only a small fraction of primary school children incurs costs to punish defectors is consistent with the finding that children’s behavior is typically closer to payoff-maximization than adult behavior (50; see also the evidence of payoff-maximizing behavior of chimpanzees in ref. 52).

Fig. 4.

Average actual punishment rates of third parties (CTR; n = 554) and expected rates of punishment by players in the TPP (n = 566) by age. Error bars, mean ± SEM.

It is interesting to note that, given actual punishment behavior, players in the TPP have higher expected payoffs from defection than from cooperation in all age cohorts, meaning that it would be a payoff-maximizing strategy to defect. Hence, if only actual punishment was important, it should not have any effect on cooperation rates (contrary to what we see in Fig. 2). However, given expected punishment rates, cooperation yields higher expected payoffs than defection for all cohorts, except for the oldest (where cooperation and defection have practically the same expected payoff) (Table S1).

Hence, cooperation in the TPP is driven by two components. First, it is a rational (expected payoff-maximizing) response to incorrect beliefs about the punishment behavior of third parties. Second, it becomes more likely as a conditionally cooperative reaction to an increase in the expected cooperation rate of a subject’s partner. The latter increase, in turn, is because of the presence of third parties. [In the Supporting Information we show support for this with a regression (Table S2) in which the likelihood to cooperate is the dependent variable. Expecting the partner to cooperate increases a subject’s likelihood of cooperation by 42 percentage points (P = 0.000), and expecting the third party to punish defection raises the likelihood of cooperation by 38 percentage points (P = 0.000). A Wald-test shows that both factors are equally strong and not significantly different from each other. In this regression, we also control for age, gender, IQ, and other covariates. Of the latter, only altruistic giving in an experiment on voluntary donations to a charity turns out to be significant (and positive, as expected).].

From a societal point of view, the TPP is more efficient than the CTR. Given the actual cooperation rate of 24.6%, the expected payoff of a player is 2.49 tokens in the CTR. Taking into account the 8% chance of losing all earnings through punishment, and considering the cooperation rate of 58% in the TPP, a player in the TPP earns on average 3.01 tokens. Subtracting from this the average costs of 0.03 tokens for the third party through punishing (8% of the 42% of defectors get punished by third parties, which costs them one token), yields a net surplus of 2.98 tokens, which is 20% higher than in the CTR.

Discussion

Third-party punishment increases cooperation already among children, aged 7 to 11 y. Across these age cohorts, we have found no significant differences in reactions to potential punishment. Most noteworthy, third-party punishment works through two channels, one of which relies on a misalignment of actual and expected punishment behavior. Subjects expect to get punished for defection much more often than third parties are actually willing to incur the costs of punishment. This mismatch between beliefs and actual behavior is persistent across all age cohorts, even though the size of the discrepancy seems to diminish for the two oldest age groups. This decrease may be related to developmental theories, which suggest that older children are more capable of understanding other people’s thoughts (51). It remains an open question at this point, however, whether older children—beyond the age of the ones in this study—would have well-calibrated expectations, thus closing the gap between actual behavior and beliefs.

Even though the punishment option is rarely executed, the expectation of punishment suffices to increase cooperation rates. The misalignment between actual and expected punishment as referred to above may, in fact, explain why field data suggest that third-party sanctioning is hardly observed, whereas cooperation rates are found to be substantial at the same time (53). The second channel through which third parties increase cooperation rates is their effect on expected cooperation rates of other players. The presence of third parties with a punishment option is expected to make others more cooperative, which in turn triggers own cooperation as a consequence of conditional cooperation. In fact, although the prevalence of conditional cooperation has been shown for adults (35, 36), our study can be interpreted as showing that already children are conditional cooperators. Moreover, our study establishes a link between conditional cooperation and the cooperation-enhancing effect of third-party punishment.

We have tried to control for the potential effects of specific design features, such as the use of the strategy method or the delayed payment procedure (see Methods). However, any experimental study has some limitations because of its specific design choices. Although our data do not give rise to the conjecture that our findings are driven by our specific design, it should be clear that variations in design may affect the behavior in experiments.

Among the avenues for future research, we see three straightforward extensions of our work. First, it would be interesting to see whether third-party reward is equally efficient in increasing cooperation as is third-party punishment, or whether positive and negative incentives work differently (54). Second, it would be a worthwhile project to study even younger children than we did in this report. We consider it an intriguing question whether at a very early age (potential) third-party punishment would be executed on the one hand, and would be effective to increase cooperation on the other hand. Third, studying how the presence of third-party observers who cannot punish affects cooperation in children would be interesting. As we measure the joint effect of observation and punishment on cooperation rates, disentangling both channels contributes to the understanding whether the presence of third parties, the possibility of punishment, or the interaction of both promotes cooperation among humans.

Methods

We conducted our experiment in all 14 elementary schools in Merano (South Tyrol, Italy) in November 2012. Merano is the second largest city in the province of South Tyrol, with about 38,000 inhabitants, of which roughly 50% are Italian speaking and 50% German speaking. Our experiment was part of a larger research project that investigated economic decision making of elementary school children. In Italy, elementary school comprises grades 1–5.

Before starting the project we obtained approval from the Internal Review Board of the University of Innsbruck, the South Tyrolean State Board of Education, and from the headmasters as well as consent from the parents of the involved children to run a series of six experimental sessions in the academic years 2011/12 and 2012/13. We got permission from 86% of parents of all elementary school children in Merano. The permissions were either granted implicitly or explicitly. Each school district separately decided whether the parents had to sign a consent form to give their child the permission to participate (opt-in) or whether participation was implicit and the parents had to sign to prohibit participation (opt-out). One of five school districts decided to implement the explicit participation consent form, the others implemented the implicit participation. In all cases, parents received a letter explaining the general purpose of the 2-y research project before the start of the experiments. Participation in each experimental session was, of course, voluntary for children, but all except a single child consented to participate.

The experiment on cooperation and punishment was the second experiment conducted with the children in the second year of the study. In that year we worked with children in grades 2–5 (while we had grades 1–5 in the first year). In total, we had 1,141 children participating in this experiment.

Each child was fetched individually from the classroom and brought to a separate room, where an experimenter explained the experiment one-to-one to the child. In this room, there were four to eight experimenters running the experiment with four to eight children at the same time, visually separated from one another. Treatments were randomized within each experimenter and experimenters had to memorize the instructions of the game and explain the game orally (in the mother-tongue of the child), with detailed visual support (see Supporting Information for experimental instructions and Fig. S2 for a sample decision sheet). The duration of the experiment was ∼20 min and it was conducted with pen and paper. Following the general procedure when conducting experiments with children (40, 55), children had to repeat the rules of the game in their own words after the explanation by the experimenter. In case of mistakes, the experimenter repeated the respective passages, and asked the child to repeat the rules once more. Twenty-one children did not manage to correctly repeat the rules, in particular the consequences of each combination of actions. Given our one-on-one explanation technique, this is a reasonable rate (40), leaving us with 1,120 children with full understanding for the analysis (Table S3). Of course, the 21 children without correct understanding were allowed to participate in the experiment until the end. Including their choices would not change any of our results.

A subject either participated in treatment CTR or TPP. Both experimental treatments had two stages; this was not known to the children at the beginning of the experiment. Only at the end of the first stage (after having made all decisions and after having answered our questions on expectations) were they informed about the second stage and its rules. Children were informed about the outcome of the two stages of the experiment only 3 mo later, when they received the presents. [As the total earnings of each child were dependent not only on own choices, but also on the decision of the partner in the experiment (who was from another school), it was not possible to calculate the final earnings of the children immediately at the end of a session. Thus, the tokens earned in the experiment were handed over at our next visit, 3 mo after this experiment took place. Given our delayed payment procedure and the high discount rates among children (56, 57), we checked whether impatient children behaved differently from more patient ones, because the former might have perceived the incentives in the experiment as less valuable than the latter. To tackle this important issue (suggested by a referee), we compared the choices (in the TPP and the CTR) of very impatient children with their more patient peers (we measured patience in an independent experiment on intertemporal preferences conducted 6 mo before the experiment for the present report was conducted). Table S2 shows that children who are categorized as more impatient do not behave differently in the PD game.].

In each stage, a child was anonymously matched with another child from the same age cohort (i.e., grade) and language group, but from a different school. This factor was common knowledge. The baseline game in the experiment was a one-shot PD (shown in Fig. 1). In this game, one child and his or her partner were endowed with two tokens each, which could be either kept or passed on to the other player. In the latter case, the tokens were doubled. This game was played in the first stage of treatment CTR where no external observer was present; hence, the game was played without a third party who could punish defection. The PD game without third party was also played in the second stage of treatment TPP. This second stage in the TPP served as a within-subjects control to study whether subjects who had experienced third-party punishment in stage one would change their behavior when third-party punishment was removed. The change was as expected, with cooperation rates dropping significantly in the absence of third-party punishment, and the data are shown in Figs. S3 and S4. In the report we do not report the second stage of treatment TPP.

In the first stage of treatment TPP the PD game was extended to a third-party punishment experiment: each player in the PD of this stage was paired with an exclusive third-party observer. This was a subject in stage 2 of the CTR. The observer was not affected by the play of the children in treatment TPP, but was endowed with one token. This token could either be kept by the child in stage 2 of the CTR or could be spent to destroy the whole payoff of the paired player in the TPP if this player chose defection. Because children in the role of an observer had played the game themselves before (in stage 1 of the CTR), they were familiar with the rules of the game and could easily condition their decision on the paired player’s choice to cooperate or defect. Of course, the observers (in the CTR) were not informed about the actual choice of the observed player (in the TPP) before making their decision on how to spend the token, meaning that we implemented a so-called strategy method (49). The decision of the observer was only implemented in case of defection. Thus, we did not allow for spiteful punishment (58), because we are primarily interested in the enforcement of a cooperation norm and not whether children are willing to punish cooperative acts. All involved participants were exactly informed about the punishment mechanism. It is also noteworthy that the observed players knew that their partner in the PD also faced a punishment threat in case of defection, because the partner also had one (different) child assigned as an observer with an opportunity to punish defection. At the very end of the session children completed a postexperimental questionnaire on demographic data (on siblings, sex, and age). Total earnings in the experiment were determined by actual decisions and also by the stated expectations. The latter were also incentivized. Subjects earned an extra token per correct guess.

As incentives, we used sweets (lollipops, small chocolates, candies), fruits (bananas, apples, oranges), and other small presents (stickers, balloons, pencils, wristbands). Children could exchange the tokens earned in the experiment into items of their choice in a so-called “experiment-store.” The cost of each item ranged from one to three tokens.

As control variables, we measured the IQ and the extent of altruism and intertemporal preferences of our participants 1 to 6 mo before the experiment on third-party punishment. IQ was elicited with a shortened version of Raven’s test. Altruism was elicited in a dictator game. Subjects were endowed with six tokens and we let them decide anonymously how many tokens to keep for themselves (and exchange them into presents in the “experiment-store”) or to donate to one of the province’s largest charities, “Menschen in Not: Kinderarmut durch Kinderreichtum,” respectively, “Umanità che ha bisogno: famiglia numerosa = famiglia povera?”, an initiative to support underprivileged children in South Tyrol. This charity is run by the well-known Caritas diocese Bolzano-Bressanone. For each token allocated to the charity we donated 50 Euro cents to the charity. Intertemporal preferences were measured with the use of a choice list. Each child had to make three decisions in which to choose either two tokens at the end of the experiment or a larger number of tokens with a delay of 4 wk. The delayed payoff was either three tokens, four tokens, or five tokens. From these choices, we could identify very impatient children (who always chose the two tokens immediately) and check whether they behaved differently from more patient children. We have data for 977 children who participated in the third-party punishment experiment and in both the altruism experiment and the intertemporal choice task, and these children are the basis for the regressions shown in Table S2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rudolf Meraner from the South Tyrolean State Board of Education (Pädagogisches Institut für die deutsche Sprachgruppe in Südtirol), the headmasters of the participating schools (Gabriella Kustatscher, Maria Angela Madera, Eva Dora Oberleiter, Brigitte Öttl, Ursula Pulyer, Vally Valbonesi), the parents of the involved children for making this study possible, and the children for participation; and an editor, two referees, Loukas Balafoutas, Nikos Nikiforakis, Karl Sigmund, the audiences at the Maastricht Behavioral and Experimental Economics Symposium 2013, and the University of Innsbruck for helpful comments. This study was supported by the Government of South Tyrol and the “Aktion D. Swarovski” at the University of Innsbruck.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.C.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1320451111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Richersen PJ, Boyd R. Not by Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. Social norms and human cooperation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8(4):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.House BR, et al. Ontogeny of prosocial behavior across diverse societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(36):14586–14591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221217110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J Theor Biol. 1964;7(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivers RL. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q Rev Biol. 1971;46(1):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.House B, Henrich J, Sarnecka B, Silk JB. The development of contingent reciprocity in children. Evol Hum Behav. 2013;34(2):86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415(6868):137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S, Richerson PJ. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3531–3535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauert C, Traulsen A, Brandt H, Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Via freedom to coercion: The emergence of costly punishment. Science. 2007;316(5833):1905–1907. doi: 10.1126/science.1141588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S. Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare. Science. 2010;328(5978):617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1183665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mussweiler T, Ockenfels A. Similarity increases altruistic punishment in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(48):19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215443110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehr E, Gächter S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(4):980–994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikiforakis N, Normann HT. A comparative statics analysis of punishment in public-good experiments. Exp Econ. 2008;11(4):358–369. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikiforakis N. Feedback, punishment and cooperation in public good experiments. Games Econ Behav. 2010;68(2):689–702. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreber A, Rand DG, Fudenberg D, Nowak MA. Winners don’t punish. Nature. 2008;452(7185):348–351. doi: 10.1038/nature06723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamagishi T. The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(1):110–116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gächter S, Herrmann B. Reciprocity, culture and human cooperation: Previous insights and a new cross-cultural experiment. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1518):791–806. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gürerk Ö, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science. 2006;312(5770):108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1123633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gintis H. Strong reciprocity and human sociality. J Theor Biol. 2000;206(2):169–179. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fehr E, Fischbacher U, Gächter S. Strong reciprocity, human cooperation and the enforcement of social norms. Hum Nat. 2002;13(1):1–25. doi: 10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gintis H, Bowles S, Boyd R, Fehr E. Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evol Hum Behav. 2003;24(3):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425(6960):785–791. doi: 10.1038/nature02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler JH. Altruistic punishment and the origin of cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(19):7047–7049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500938102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathew S, Boyd R. Punishment sustains large-scale cooperation in prestate warfare. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(28):11375–11380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105604108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinada M, Yamagishi T. Punishing free riders: Direct and indirect promotion of cooperation. Evol Hum Behav. 2007;28(5):330–339. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol Hum Behav. 2004;25(2):63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpenter JP, Matthews PH, Ong’ong’a O. Why punish? Social reciprocity and the enforcement of prosocial norms. J Evol Econ. 2004;14(4):407–429. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charness G, Cobo-Reyes R, Jiménez N. An investment game with third-party intervention. J Econ Behav Organ. 2008;68(1):18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter JP, Matthews PH. Norm enforcement: Anger, indignation or reciprocity? J Eur Econ Assoc. 2012;10(3):555–572. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauser MD. Costs of deception: cheaters are punished in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(24):12137–12139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clutton-Brock TH, Parker GA. Punishment in animal societies. Nature. 1995;373(6511):209–216. doi: 10.1038/373209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Rohr CR, et al. Impartial third-party interventions in captive chimpanzees: A reflection of community concern. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e32494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riedl K, Jensen K, Call J, Tomasello M. No third-party punishment in chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(37):14824–14829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203179109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan C-P. Theaching children cooperation—An application of experimental game theory. J Econ Behav Organ. 2000;41(3):191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keser C, van Winden F. Conditional cooperation and voluntary contributions to public goods. Scand J Econ. 2000;102(1):23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ Lett. 2001;71(3):397–404. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurzban R, Houser D. Experiments investigating cooperative types in humans: A complement to evolutionary theory and simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(5):1803–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408759102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt MFH, Rakoczy H, Tomasello M. Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. Cognition. 2012;124(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joyce WB. On the free-riding problem in cooperative learning. J Educ Bus. 1999;74(5):271–274. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fehr E, Bernhard H, Rockenbach B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature. 2008;454(7208):1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature07155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parsons T. The school class as a social system: Some of its functions in American Society. Harv Educ Rev. 1959;29(4):297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson DW. Student-student interaction: The neglected variable in education. Educ Res. 1981;10(1):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomasello M, Call J, Hare B. Chimpanzees understand psychological states—The question is which ones and to what extent. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7(4):153–156. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Astington JW. The Child’s Discovery of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harbaugh W, Krause K, Berry TR. GARP for kids: On the development of rational choice behavior. Am Econ Rev. 2001;91(5):1539–1947. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Call J, Tomasello M. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? 30 years later. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(5):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fehr E, Schmidt K. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q J Econ. 1999;114(3):817–868. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolton GE, Ockenfels A. ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(1):166–193. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brandts J, Charness G. The strategy versus the direct-response method: A first survey of experimental comparisons. Exp Econ. 2011;14(3):375–398. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camerer FC. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Selman RL. Taking another’s perspective: Role-taking development in early childhood. Child Dev. 1971;42(6):1721–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen K, Call J, Tomasello M. Chimpanzees are rational maximizers in an ultimatum game. Science. 2007;318(5847):107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1145850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balafoutas L, Nikiforakis N. Norm enforcement in the city: A natural field experiment. Eur Econ Rev. 2012;56(8):1773–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gneezy U, Meier S, Rey-Biel P. When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25(4):191–210. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harbaugh W, Krause K. 1999. Economic experiments that you can perform at home on your children. Working Paper, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. Available at https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/56/UO-1999-1_Harbaugh_Economic_Experiments%5B2%5D.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 28, 2013.

- 56.Castillo M, Ferraro PJ, Jordan JL, Petrie R. The today and tomorrow of kids: Time preferences and educational outcomes of children. J Public Econ. 2011;95(11):1377–1385. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bettinger E, Slonim R. Patience among children. J Public Econ. 2007;91(1–2):343–363. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herrmann B, Thöni C, Gächter S. Antisocial punishment across societies. Science. 2008;319(5868):1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1153808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.