Significance

Regulation of tissue growth is essential for metazoan development and adult homeostasis. The Hippo (Hpo) pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling cascade that has emerged as a crucial regulator of tissue size by virtue of its control of cell proliferation and cell death. Multiple epithelial architecture inputs converge on Hpo signaling, allowing tissues to quickly respond to disruptions in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions. Here, we show that the polarity protein Crumbs promotes the apical localization and degradation of the Hpo pathway protein Expanded, by the SCFSlmb/β-TRCP ubiquitin ligase. This ubiquitin-dependent mechanism could potentially allow the dynamic regulation of Hpo signaling in response to changes in polarity.

Keywords: Drosophila, development, signal transduction

Abstract

In epithelial tissues, growth control depends on the maintenance of proper architecture through apicobasal polarity and cell–cell contacts. The Hippo signaling pathway has been proposed to sense tissue architecture and cell density via an intimate coupling with the polarity and cell contact machineries. The apical polarity protein Crumbs (Crb) controls the activity of Yorkie (Yki)/Yes-activated protein, the progrowth target of the Hippo pathway core kinase cassette, both in flies and mammals. The apically localized Four-point-one, Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin domain protein Expanded (Ex) regulates Yki by promoting activation of the kinase cascade and by directly tethering Yki to the plasma membrane. Crb interacts with Ex and promotes its apical localization, thereby linking cell polarity with Hippo signaling. We show that, as well as repressing Yki by recruiting Ex to the apical membrane, Crb promotes phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Ex. We identify Skp/Cullin/F-boxSlimb/β-transducin repeats-containing protein (SCFSlimb/β-TrCP) as the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex responsible for Ex degradation. Thus, Crb is part of a homeostatic mechanism that promotes Ex inhibition of Yki, but also limits Ex activity by inducing its degradation, allowing precise tuning of Yki function.

Multicellular organisms need to monitor and control their size throughout development and adult life in the face of challenges such as fast developmental growth and constant tissue turnover during adult homeostasis (1). In addition to secreted growth factors and systemic cues such as nutrient levels, much of the control of tissue growth takes place at the local level through cell–cell and cell–matrix contacts. This is particularly important in epithelial cells, where maintenance of normal tissue architecture is crucial to size control, and loss of organization is associated with tumor growth and dissemination (2). The Hippo (Hpo) pathway, a conserved regulator of tissue growth, has emerged as a key effector of tissue architecture in size control (3, 4). The Hpo pathway represses growth by limiting the activity of the progrowth transcriptional coactivator Yorkie (Yki, Yes-Activated Protein, YAP in mammals) (5, 6). This is primarily achieved through the activity of a core kinase cascade that consists of the upstream kinase Hpo (Mammalian Ste20-like 1/2, MST1/2 in mammals) and the downstream kinase Warts (Wts, Large Tumor Suppressor 1/2, LAST1/2 in mammals), as well as by a number of kinase-independent mechanisms that tether Yki/YAP in the cytoplasm.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Hpo pathway activity is tightly coupled to epithelial architecture. Firstly, Yki/YAP transcriptional activity has been shown to depend on the structure of the actin cytoskeleton, with F-actin promoting YAP nuclear translocation, although the precise mechanisms and the involvement of the core kinase cascade in this process remain unclear (7–10). Secondly, the basolateral polarity proteins Scribbled and Lethal(2)giant larvae (Lgl) have been shown to promote Hpo pathway activity (11–13). Thirdly, the adherens junction protein α-catenin has been proposed to function as a membrane tether for YAP in keratinocytes (14). Finally, the apical protein Crumbs (Crb) antagonizes Yki/YAP activity, both in Drosophila and mammals (13, 15–19).

Crb is a transmembrane protein that contains multiple EGF repeats in its large extracellular domain. crb mutants display severe epithelial disorganization in the embryonic epidermis, leading to widespread cell death (20). Crb is a key apical polarity determinant that recruits other polarity proteins through its short 37 amino acid (aa) intracellular domain. These include Par-6 and its partner atypical Protein Kinase C (aPKC), as well as the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGU.K) protein Stardust (Sdt) (21–26). In addition to a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (PBM), which binds Sdt, Crb also contains a juxtamembrane Four-point-one, Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin (FERM)-binding motif (FBM) that has been reported to bind the FERM domain proteins Yurt and Moesin (Moe) (27, 28).

Beside its well-documented role in polarity, Crb is also required for normal growth control, because loss of crb function leads to tissue overgrowth (13, 15–18, 29). This has been ascribed to a role in both Notch and Hpo signaling (13, 15, 17, 18, 29). The function of Crb in Hpo signaling is thought to involve the recruitment of the FERM domain protein Expanded (Ex) to the apical membrane (15–18). Indeed, the FERM domain of Ex can bind the Crb FBM in vitro (17). Once apically localized, Ex forms a complex with the scaffold proteins Kibra and Merlin (Mer), which promotes inhibitory phosphorylation of Yki by Wts (30–32). In addition, Ex is thought to act as an apical tether for Yki by binding the Yki WW domains through its Pro-Pro-X-Tyr (PY) motifs (33, 34). In mammals, the Crb ortholog CRB3 and the PY-containing protein Angiomotin (Amot) are thought to interact in a functionally equivalent complex that represses YAP and its paralogue TAZ (19, 35, 36).

In agreement with a proposed role for Crb as a transmembrane receptor for the Hpo pathway, loss of crb promotes expression of Yki target genes, such as ex and diap1/thread (15, 17, 18). However, paradoxically, overexpression of the intracellular domain of Crb (Crbintra) leads to strong tissue overgrowth and Yki target gene derepression (13, 15, 18, 37). Although this could be due to a dominant-negative effect, it is important to note that Crbintra overexpression leads to loss of apical Ex in developing wings and eyes, whereas coexpression of Crbintra and Ex in cell culture leads to Ex phosphorylation and reduced expression (3, 13, 15, 17, 18, 38). In the present study, we show that Crb recruits Ex to the plasma membrane for phosphorylation and ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Using an affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) approach, we identify Skp/Cullin/F-boxSlimb/β-transducin repeats-containing protein (SCFSlimb/β-TrCP) as the E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for Crb-dependent Ex degradation. Crb promotes Ex:Slmb association via a phosphodegron C terminal to the Ex FERM domain. Our data suggest that during epithelial tissue growth, Crb not only recruits Ex to its site of activity at the apical membrane, but also induces its degradation to prevent excess Yki silencing. We propose that Crb is part of a homeostatic mechanism that fine tunes Hpo signaling and thus epithelial tissue growth in response to cell and tissue integrity.

Results

Disruption of crb Function Affects Ex Apical Localization and Protein Levels.

Recent reports have uncovered a role for the apical polarity determinant Crb in the regulation of Drosophila Hpo signaling (13, 15, 17, 18). However, there are discrepancies in the literature regarding the effect of crb loss or Crbintra overexpression on the subcellular localization and protein levels of Ex (13, 15–18).

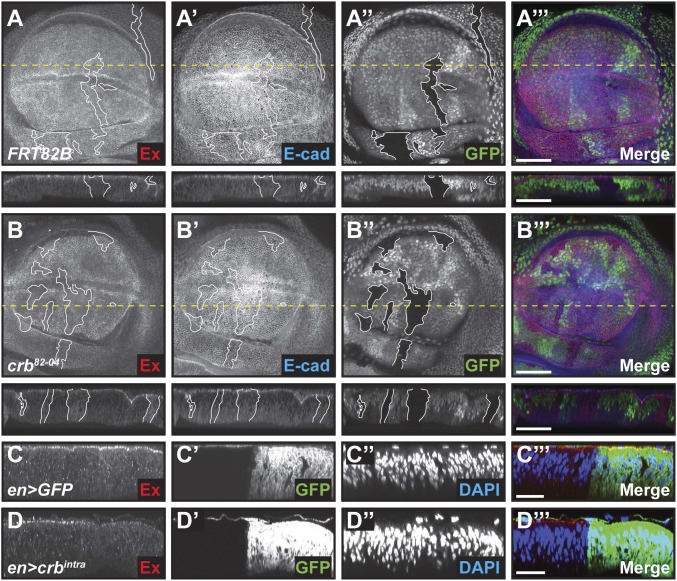

To resolve these differences, we analyzed the subcellular localization of Ex in crb mutant epithelial tissue as well as in tissue overexpressing Crbintra. In control mitotic clones, Ex localized at the apical surface of cells (Fig. 1A). In contrast, crb loss-of-function clones, using two different alleles, displayed reduced levels of apical Ex, which was instead found throughout the cytoplasm of mutant cells (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 A and D). This effect was specific to Ex and not the consequence of a more severe effect on cell polarity, as subcellular localization of E-cadherin (E-cad) and aPKC were unaffected by loss of crb (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1C). This suggests that Crb is required for correct membrane-associated localization of Ex (15–18). Next, we used the GAL4/UAS system to express Crbintra specifically in the posterior compartment of the developing wing using a GAL4 transgene under the control of the engrailed (en) promoter. Expression of Crbintra caused a dramatic decrease in Ex protein levels at the apical surface with no associated cytoplasmic increase (Fig. 1 C and D and Fig. S1E), suggesting that excess Crb destabilizes Ex at the apical membrane (15, 18). Thus, although expression of Crbintra and crb loss of function similarly inhibit Hpo pathway function, based on Ex localization, the mechanisms by which they promote this outcome are markedly distinct at the molecular level.

Fig. 1.

Crb regulates Ex subcellular localization in vivo. (A and B) crb loss leads to Ex delocalization to the cytoplasm. XY and transverse sections (indicated in XY sections by a dashed yellow line) of third instar wing imaginal discs containing clones (marked by the absence of GFP and highlighted by white borders) of wild-type cells (A–A′′′) or cells mutant for crb (crb82-04, B–B′′′) and stained for Ex (A and B) and E-cad (A′ and B′). A′′ and B′′ denote GFP, whereas A′′′ and B′′′ are merged images. (C and D) Crbintra expression causes depletion of Ex protein levels. Transverse sections of third instar wing imaginal discs expressing UAS-GFP (C–C′′′) or UAS-crbintra (D–D′′′) in the posterior compartment under the control of engrailed (en)-GAL4 and stained for Ex (C and D). GFP (C′ and D′) marks the posterior compartment of the wing, whereas DAPI (C′′ and D′′) marks nuclei. C′′′ and D′′′ are merged images. In XY sections, ventral is up, whereas apical is up in transverse sections. (Scale bars, 50 μm in A and B and 25 μm in C and D.)

Crb Promotes Ex Phosphorylation and Degradation in a FERM-Binding Motif-Dependent Manner.

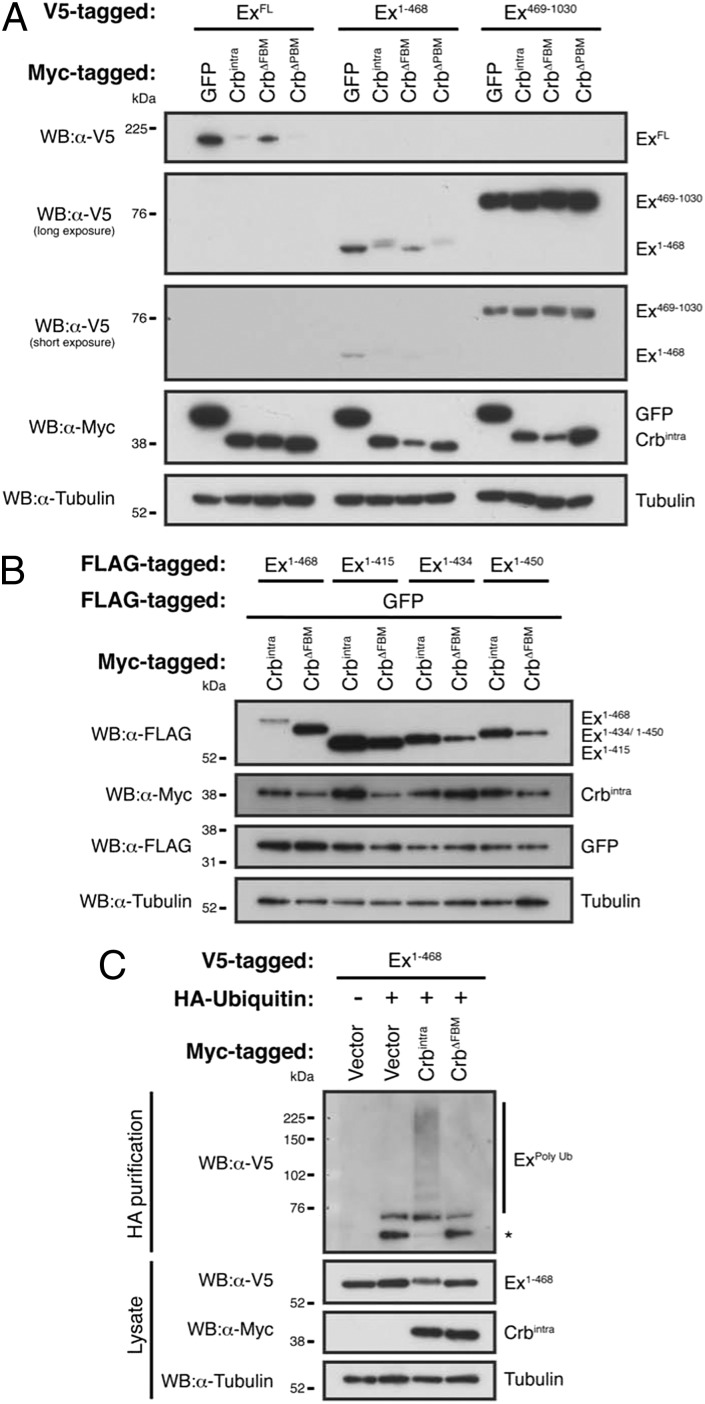

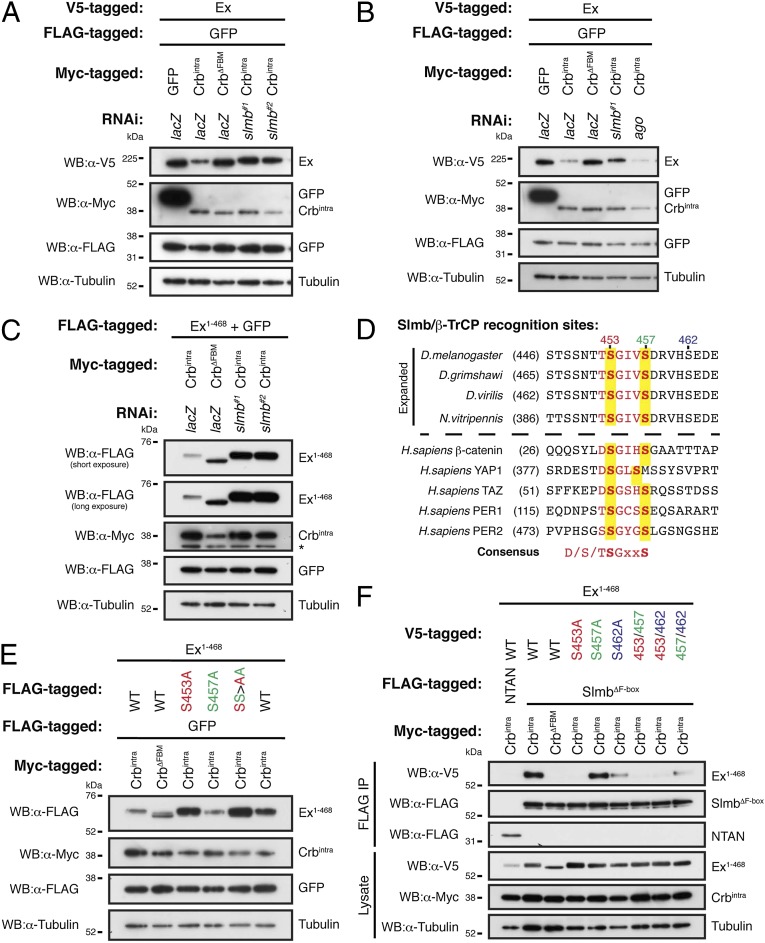

Next, we sought to characterize the molecular mechanism by which Crbintra regulates Ex protein levels. Expression of Crbintra in Drosophila S2 cells has been shown to promote delayed electrophoretic mobility of Ex, which is thought to be the result of a phosphorylation event (17). This effect of Crbintra depends on its FERM-binding motif (FBM) but independent of its PDZ-binding motif (PBM) (17). Moreover, it has been suggested that Crbintra expression promotes depletion of Ex levels in a proteasome-dependent manner (18). In agreement with these findings, we observed that coexpression of Crbintra and Ex in S2 cells caused a mobility shift and strong reduction of Ex protein levels, which was FBM- but not PBM-dependent (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Ex is phosphorylated, ubiquitylated, and degraded in a Crbintra-dependent manner. (A) Crbintra promotes degradation of the Ex FERM domain in an FBM-dependent manner. V5-tagged Ex, Ex1–468 or Ex469–1,030 were cotransfected with Myc-tagged GFP, Crbintra, CrbΔFBM, or CrbΔPBM in S2 cells for 48 h before lysis. Lysates were processed for immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. Note that Crbintra and CrbΔPBM caused a mobility shift and depletion of Ex and Ex1–468 but not of Ex469–1,030. (B) Ex truncations lacking the sequence neighboring the FERM domain are refractory to Crbintra-induced changes. The electrophoretic mobility and stability of FLAG-tagged Ex truncations was assessed upon cotransfection with Myc-tagged Crbintra or CrbΔFBM. GFP was used as transfection efficiency control. (C) Crbintra induces Ex1–468 ubiquitylation in an FBM-dependent manner. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs for 48 h. Following lysis under denaturing conditions, ubiquitylated proteins were isolated using anti-HA antibodies targeting proteins modified with transfected HA-tagged ubiquitin. The presence of Ex and Crbintra was assessed with the indicated antibodies. Note the protein band smear corresponding to ubiquitin-modified Ex1–468 when Crbintra was present. Tubulin was used as loading control. Asterisk denotes nonspecific band.

The effect of Crbintra on Ex electrophoretic mobility has been previously mapped to the amino-terminal half of Ex (amino acids 1–709) (17). Crbintra and Ex are thought to interact directly via Crbintra FBM, prompting us to test whether the effect of Crbintra is dependent on the FERM domain of Ex (17). To this end, we generated nonoverlapping truncation constructs of Ex that encompass the region known to be affected by Crbintra. We found that Ex1–468, which comprises the FERM domain, but not Ex469–1030, was sufficient to replicate the effect of Crbintra on full-length Ex protein levels and mobility shift (Fig. 2A). Following further mapping experiments, we found that Ex1–468 is the minimal region of Ex required for Crbintra-mediated effects (Fig. 2B). Removal of the last 18 aa of Ex1–468 was sufficient to stabilize this truncated version of Ex and to prevent its mobility shift in the presence of Crbintra. These results indicate that Crbintra regulates Ex protein levels and that a region immediately C terminal to the FERM domain that comprises amino acids 450–468 is essential for this regulation. This region of Ex could be the site of Crbintra-induced modification or could be a docking site for the protein(s) involved in the modification. As for full-length Ex, the stability of the Ex1–468 fragment was rescued by treatment with proteasome inhibitors, and the mobility shift was reverted upon phosphatase treatment (Fig. S2 A and B) (17, 18).

Given that depletion of Ex depends on proteasome function, we assessed whether Crbintra expression could trigger ubiquitylation of Ex1–468 by performing cell-based ubiquitylation assays (see Materials and Methods for details). Indeed, Ex1–468 was specifically ubiquitylated in response to Crbintra expression (Fig. 2C). In contrast, CrbΔFBM (a Crbintra version with mutations in conserved residues of the FBM) was unable to induce Ex1–468 ubiquitylation, indicating that the FBM is essential for Crb to promote Ex ubiquitylation and degradation. It has recently been suggested that Crbintra is unable to completely rescue phenotypes arising from crb loss of function and might therefore have different biological properties than full-length Crb (CrbFL) (39). Importantly, expression of CrbFL also promoted Ex ubiquitylation and degradation, suggesting that Crb is responsible for tightly controlling Ex protein levels in S2 cells (Fig. S2 C and D).

As Ex appears to be targeted by Crbintra via its FERM domain, this raised the possibility that Crb regulates the phosphorylation state and protein levels of additional FERM domain-containing proteins. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether Crbintra was able to regulate Merlin (Mer), Moesin (Moe) and Pez, three FERM domain-containing proteins that have been associated with either Hpo signaling or regulation of cell polarity (3, 28, 40–42). However, in contrast to Ex, the FERM proteins Mer, Moe, and Pez were not affected by coexpression of Crbintra in S2 cells (Fig. S2 E and F). Taken together, these data suggest that Crbintra targets Ex for phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and proteasome-mediated degradation in an FBM-dependent manner.

Identification of Slimb/β-TrCP as an Ex-Associated Protein.

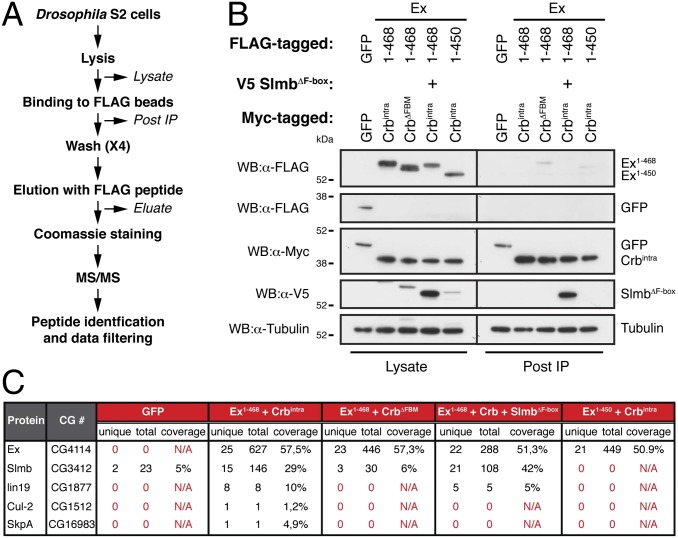

To characterize the molecular events involved in the Crbintra-mediated regulation of Ex, we performed AP of Ex1–468 followed by MS analysis (Fig. 3A). We initially sought to identify putative phosphorylation sites in Ex specifically modified in response to Crbintra expression (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3A). We affinity purified FLAG-tagged Ex1–468 from S2 cells in the presence or absence of Crbintra and achieved 40–50% peptide coverage (Fig. S3B). MS analysis of purified Ex1–468 revealed four sites, the phosphorylation of which was potentiated by Crbintra expression (Ser196, Tyr227, Ser416, and Tyr432). However, subsequent mutational analysis failed to reveal a function for the putative phosphorylation sites in the regulation of Ex stability or phosphorylation (Fig. S3C). While analyzing our Ex1–468 MS data, we identified peptides for additional proteins that have a similar molecular weight and therefore migrate on SDS/PAGE gels in the vicinity of Ex1–468. Interestingly, we noted that peptides predicted to correspond to the F-box protein Slimb/β-TrCP (Slmb) were detected in Ex immunoprecipitations specifically upon coexpression with Crbintra (Fig. S3B). Slmb is the substrate-targeting subunit of a multicomponent ubiquitin ligase complex termed the Skp–Cullin–F-box (SCF) complex. This complex is involved in the ubiquitylation and proteasomal targeting of several proteins, typically in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (43–46). As Ex is phosphorylated, ubiquitylated and degraded in a Crbintra-dependent manner, this raises the possibility that Slmb is involved in the regulation of Ex protein levels.

Fig. 3.

Identification of Ex-associated proteins via a MS-based approach. (A) Schematic representation of MS analysis workflow. (B) Immunoprecipitation efficiency control before MS analysis. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 plus LLnL for 4 h before cell lysis. FLAG-tagged proteins were isolated from cell lysates using FLAG-agarose. Immunoblots showing presence of proteins prior and after incubation with FLAG-agarose beads were probed with the indicated antibodies. Note that FLAG-tagged proteins are efficiently depleted from postimmunoprecipitation samples. Tubulin was used as loading control. (C) Summary of AP-MS results. CG# denotes CG number from FlyBase. Unique and total denote, respectively, the number of unique peptides and total number of peptides detected in MS analysis for a specific protein. Coverage indicates percentage of protein that is covered by peptides recovered in MS analysis for a specific protein. N/A denotes not applicable.

To test this hypothesis, we extended our MS-based analysis to the full complement of Ex-interacting proteins by purifying Ex1–468 in the presence of Crbintra or CrbΔFBM (Fig. 3 B and C). Additionally, we included samples containing an F-box mutant version of Slmb (SlmbΔF-box, which prevents association with the SCF complex), the Ex1–450 truncation, which was refractory to Crbintra expression, and FLAG-tagged GFP as control (47) (Fig. 3 B and C). We detected a substantial increase in the number of Slmb peptides in samples where wild-type Crbintra was present. Importantly, in those samples, we also detected peptides corresponding to three known Slmb-interacting proteins, which are part of the SCF complex (Lin19 or Cul-1, Cul-2, and SkpA), suggesting that Slmb associates with Ex in a Crbintra-induced manner, likely as part of a larger SCF complex.

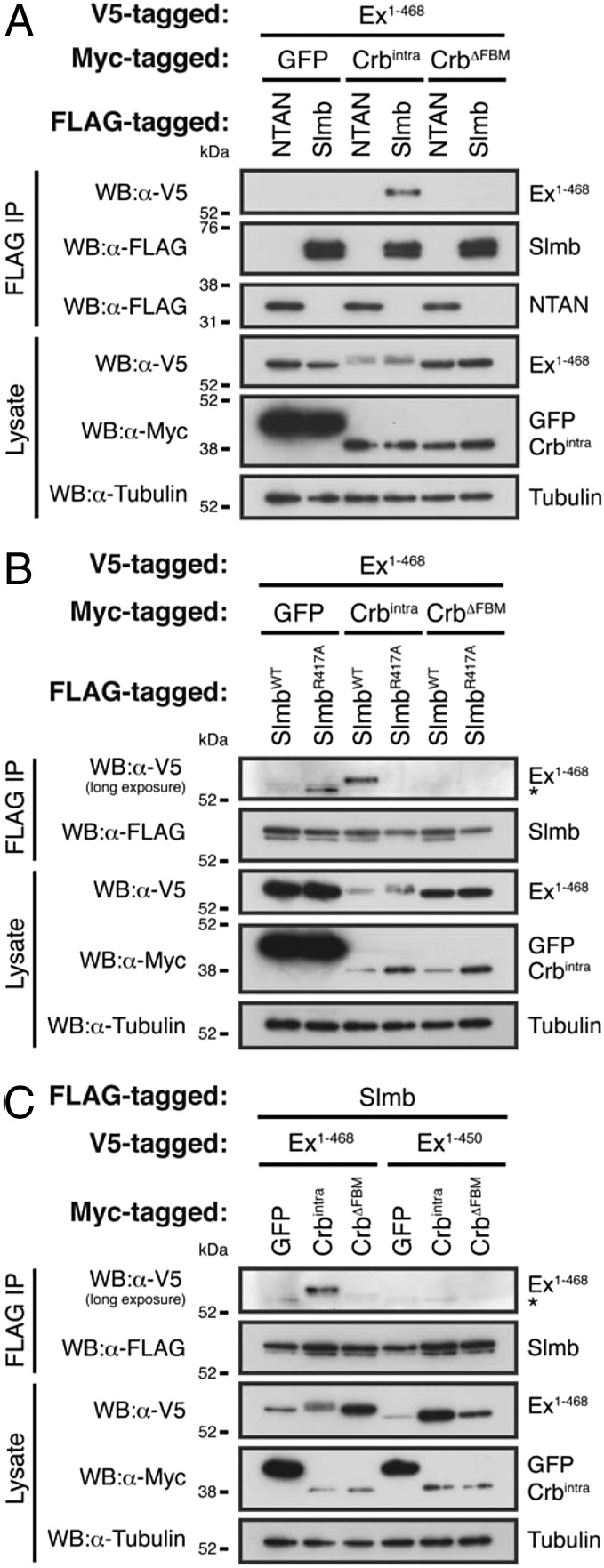

Slmb Specifically Associates with Ex in a Crbintra- and WD40-Dependent Manner.

Next, we validated our AP-MS analysis by performing coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments from S2 cell lysates. We initially tested whether Crbintra promotes the Slmb:Ex association in an FBM-dependent manner, as suggested by our MS results. Indeed, FLAG-tagged Slmb readily interacted with Ex1–468 when wild-type Crbintra was coexpressed, but failed to do so when CrbΔFBM was used (Fig. 4A). In addition, we tested whether this association was specific to Ex or whether Crbintra induced a more general association of Slmb with other FERM domain-bearing proteins. Contrary to what we observed for Ex, Crbintra expression in S2 cells failed to induce the specific binding of Slmb to Mer or Moe (Fig. S4 A and B).

Fig. 4.

Molecular requirements of Ex:Slmb association. (A) Crbintra promotes Ex:Slmb association in an FBM-dependent manner. Co-IPs were performed with FLAG-tagged NTAN or Slmb and V5-tagged Ex1–468, in the presence of Myc-tagged GFP, Crbintra, or CrbΔFBM. Expression and the presence of copurified proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) The Ex:Slmb association is dependent on the ability of Slmb to recognize phosphorylated peptides. Co-IPs were performed as in A. Immunoblots were analyzed with the indicated antibodies to reveal expression and copurification of the indicated proteins. Note that mutation of the Slmb WD40 repeat domain abrogates binding to Ex1–468. (C) Slmb fails to interact with a nonphosphorylatable and stable form of Ex. Immunoprecipitations were executed as in A and immunoblots were analyzed for the expression and binding of the indicated proteins using the specified antibodies. Tubulin was used as loading control. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands.

Slmb is known to interact with its substrates via the recognition of phosphorylated sequences termed phosphodegrons (43, 48–60). The WD40 repeat motif present at the C terminus of Slmb is crucial for its ability to recognize phosphorylated targets (61). Within the WD40 repeat motif of F-box proteins, which organizes itself as a β-propeller structure, specific residues contact the phosphorylated residues on the substrate, allowing its recognition and subsequent ubiquitylation (61, 62). Mutation of Arg474 in human β-TrCP1 completely abrogates its ability to interact with and target its substrates for degradation (61). Consistently, when we mutated the equivalent residue in Slmb (R471A mutation), the association with Ex in the presence of Crbintra coexpression was lost (Fig. 4B). Conversely, Ex1–450, which is resistant to Crb-induced degradation, did not associate with Slmb (Fig. 4C). Therefore, our results are consistent with Crbintra promoting the association of Slmb and Ex.

Slmb Is Required for Crbintra-Induced Degradation of Ex.

The Slmb:Ex association correlates with the phosphorylation state and the relative stability of Ex. To determine whether Slmb is required for the effect of Crbintra expression on Ex protein levels, we performed experiments using RNAi-mediated depletion of Slmb. Depletion of Slmb protein using two nonoverlapping dsRNA sequences targeting slmb affected the ability of Crbintra to reduce Ex levels (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, RNAi-mediated depletion of Slmb stabilized the phosphorylated form of Ex, indicating that Slmb is only required for Crbintra-mediated Ex degradation and does not affect the ability of Crbintra to promote Ex phosphorylation. We tested whether the role of Slmb in the regulation of Ex protein levels was specific or if it was a general effect of depleting F-box proteins. RNAi-mediated depletion of Archipelago (Ago), the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian FBW7, a WD40 repeat domain containing F-box protein, had no effect on the ability of Crbintra to down-regulate Ex protein levels (Fig. 5B) (63, 64). As for full-length Ex, Ex1–468 was markedly stabilized in the presence of Crbintra when combined with RNAi targeting slmb (Fig. 5C). Our data suggest that Slmb acts downstream of Crbintra and promotes the ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of Ex.

Fig. 5.

Slmb recognition consensus site mediates the regulation of Ex protein stability. (A–C) RNAi-mediated depletion of Slmb prevents Crbintra-induced Ex degradation. S2 cells were treated with the indicated dsRNAs for 24 h before transfection with Ex (A and B) or Ex1–468 (C) and the indicated constructs. Cell lysates were processed for immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. GFP and tubulin were used as transfection efficiency and loading control, respectively. Asterisk denotes nonspecific band. (D) Ex contains a Slmb recognition consensus site. Ex sequences were aligned as indicated in Materials and Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate starting aa residue of the depicted sequences. Sequences above dashed line are of Ex orthologs from arthropod species, whereas below the dashed line are sequences from known Slmb substrates. Red indicates Slmb consensus sequence and yellow background highlights the putative phosphorylated Ser residues. (E) Mutation of the Slmb recognition site prevents Ex depletion. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and lysates were processed for immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. GFP and tubulin were used as transfection efficiency and loading control, respectively. (F) Mutation of Slmb recognition site abrogates the Slmb:Ex interaction. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. Following lysis, FLAG-tagged proteins were purified using FLAG-agarose beads and samples were processed for Western blotting analysis using the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as loading control.

Slmb targets proteins for degradation following the recognition of specific sequences present in bona fide substrates (43, 46). Slmb recognition sites often follow the DSGϕXS consensus sequence (where ϕ and X denote hydrophobic and any aa, respectively), which can be phosphorylated on one or both Ser residues (43, 46). However, many instances exist where known Slmb targets do not exactly conform to this consensus sequence or to the requirement for the phosphorylated residues, and rather have a looser Slmb recognition sequence (43). Because we uncovered a role for Slmb in the regulation of Ex protein levels, we asked whether a Slmb recognition site exists in the Ex protein sequence. Sequence analysis revealed that Ex contains one site that closely resembles a Slmb recognition consensus site (452TSGIVS457), and two putative recognition sites that do not conform to the canonical consensus (225STYVAS230 and 1116STQNIS1121) (Fig. 5D). The observation that Crbintra destabilizes the Ex1–468 truncation, but not the Ex1–450 truncation, with which it fails to interact, suggests that the motif most closely matching the Slmb recognition consensus site (amino acids 452–457) is crucial for regulation of Ex protein levels. Importantly, this putative Slmb recognition site seems to be evolutionarily conserved both at the sequence level and with regards to its positioning relative to the FERM domain (Fig. 5D and Fig. S5A). In agreement with the data presented above, Drosophila Mer, Moe, and Pez lack a Slmb recognition consensus site in the equivalent region (Fig. S5B).

Next, we tested the functional relevance of the Slmb recognition consensus sequence we identified in Ex. We chose to mutate the Ser residues present in the consensus sequence (S453A, S457A, and SS453/7AA mutations), as these are predicted to be targets for phosphorylation and to be required for Slmb substrate recognition (43, 46). Mutation of Ser453, alone or in combination with Ser457, was sufficient to prevent Ex degradation following Crb coexpression (Fig. 5E and Fig. S2C). Mutation of Ser457 alone failed to protect Ex from degradation in the presence of Crbintra. In the context of full-length Ex, mutation of Ser453 was also able to prevent the degradation of Ex in the presence of Crbintra, albeit to a lesser extent than in Ex1–468, suggesting that the noncanonical sites may participate in Ex:Slmb association (Fig. S5C). These results suggest that Ser453 is essential for Crbintra- and Slmb-mediated regulation of Ex.

Notably, mutation of Ser453 in isolation or in combination with Ser457 was insufficient to reverse the Ex mobility shift caused by phosphorylation (Fig. 5E and Fig. S5C). This indicates that, in response to Crbintra overexpression, Ex is probably phosphorylated at multiple residues located in the vicinity of the Slmb recognition sequence. This observation is also consistent with a potential priming phosphorylation mechanism, which is commonly observed in known Slmb targets such as β-catenin (43, 46). Slmb-mediated degradation of β-catenin is triggered in the absence of Wingless/Wnt (Wg/Wnt) signaling and involves the initial phosphorylation of residues outside the Slmb recognition site by CKIα (65). This priming event leads to subsequent phosphorylation of the Ser residues in the target recognition sequence by GSK3β, inducing Slmb binding, ubiquitylation, and degradation of β-catenin (65).

We therefore assessed whether mutation of conserved Ser residues within and outside the Slmb recognition site perturbed the Crbintra-induced interaction of Ex with Slmb. We found that mutation of Ser453 completely abrogated the association between Slmb and Ex, in agreement with the fact that Ex1–468 S453A is not destabilized in the presence of Crbintra (Fig. 5F and Fig. S5D). In contrast, Ex1–468 S457A interacted with Slmb with similar affinity as its wild-type counterpart (Fig. 5F). Mutating Ser462, which lies immediately downstream of the Slmb recognition site, caused a significant reduction in the Crb:Ex association but did not abrogate it (Fig. 5F).

Slmb Ubiquitylates Ex and Regulates Its Protein Levels in Vivo.

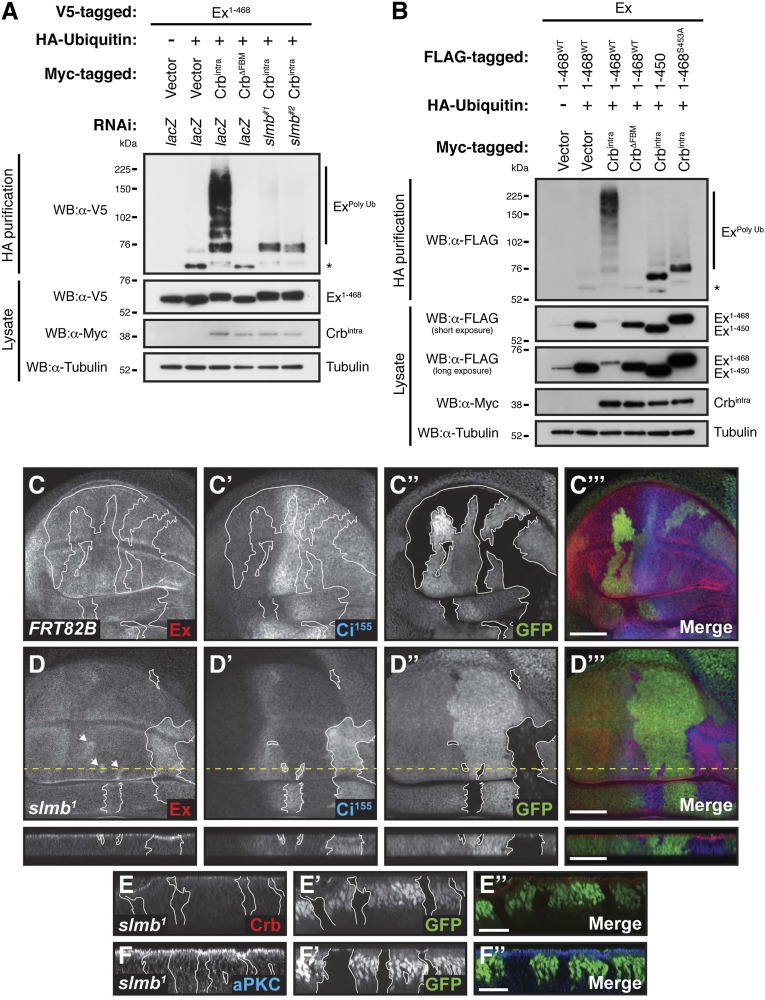

Because Slmb is part of an SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, we tested its role in the Crbintra-induced ubiquitylation of Ex. Coexpression with Crbintra caused robust ubiquitylation of Ex1–468, whereas expression of CrbΔFBM failed to trigger Ex ubiquitylation (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, RNAi-mediated depletion of Slmb completely abrogated the ubiquitylation of Ex induced by Crbintra expression (Fig. 6A). In sharp contrast, Ex1–450, the Ex truncation that lacks the Slmb recognition site, was not ubiquitylated in the presence of Crbintra (Fig. 6B). We further tested the involvement of Slmb in Ex ubiquitylation by testing the effect of mutating the Slmb recognition site present in Ex. Mutation of Ser453, which is essential for Slmb-mediated regulation of Ex protein levels, completely abrogated Crb-induced Ex ubiquitylation (Fig. 6B and Fig. S2D). Thus, Slmb is essential for ubiquitylation of Ex downstream of Crb.

Fig. 6.

Slmb is required for Crbintra-induced ubiquitylation of Ex and regulation of its protein levels in vivo. (A) Slmb depletion prevents Ex ubiquitylation in response to Crbintra expression. S2 cells were treated with dsRNA for 24 h before transfection with the indicated constructs and cells were treated with MG132 plus LLnL for 4 h before cell lysis. Following lysis under denaturing conditions, ubiquitylated proteins were isolated using anti-HA antibodies. The presence of Ex and Crbintra was assessed with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin was used as loading control. (B) Absence or mutation of the Slmb recognition site in Ex inhibits its ubiquitylation. S2 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs for 48 h. Following lysis under denaturing conditions, ubiquitylated proteins were isolated using anti-HA antibodies. Tubulin was used as loading control. Asterisks denote nonspecific bands. (C–F) Loss of Slmb function leads to increased protein levels of Ex and Ci155 in vivo. XY and transverse sections (indicated in XY sections by dashed yellow line) of third instar wing imaginal discs containing clones (marked by the absence of GFP and highlighted by white borders and arrowheads) of wild-type cells (C–C′′′) or cells mutant for slmb (slmb1, D–F′′) and stained for Ex (C and D), Ci155 (C′ and D′), Crb (E), and aPKC (F). C′′, D′′, E′, and F′ denote GFP, whereas C′′′, D′′′, E′′, and F′′ are merged images. In XY sections, ventral is up and anterior is to the Right, whereas apical is up in transverse sections. (Scale bars, 50 μm in C and D and 25 μm in E and F.)

To determine whether Slmb also regulates Ex protein levels in vivo, we examined Ex protein in heat-shock Flipase/Flipase recombination target (FLP/FRT)-generated clones for slmb1, a strong hypomorph allele that has been reported to affect levels of Slmb targets such as Armadillo (Drosophila β-catenin ortholog) and the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway transcription factor Cubitus interruptus (Ci) (66). Whereas control mitotic clones had no effect on the levels of the precursor form of Ci (Ci155), slmb1 mutant clones exhibited a substantial increase in Ci155 levels (Fig. 6 C and D). Ex protein levels were similarly up-regulated in slmb1 mutant tissues, particularly in the wing pouch, whereas wild-type clones were unaffected (Fig. 6 C and D). Importantly, the increased levels of Ex were not due to changes in Crb levels, because slmb mutant clones displayed no changes in Crb staining (Fig. 6E). Additionally, apicobasal cell polarity in slmb1 clones was not severely affected, as visualized by aPKC staining (Fig. 6F). Thus, Slmb can negatively regulate Ex in vivo, supporting the idea that Crb acts together with Slmb to induce Ex ubiquitylation and degradation at the apical plasma membrane.

Discussion

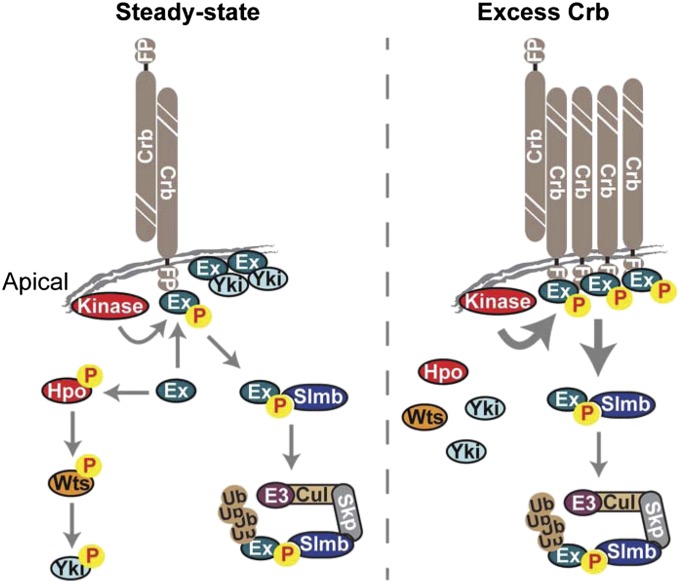

Recent work in flies and mammals has implicated the apical polarity determinant Crb as a transmembrane receptor for Hpo signaling (13, 15, 17, 18). Accordingly, clonal loss of crb function leads to Yki derepression and increased growth. However, the observation that Crb is required for Ex membrane localization apparently conflicts with the finding that Crbintra overexpression reduces Ex levels and, like crb loss of function, leads to increased Yki activity (13, 15, 17, 18). Here, we reconcile these findings by showing that Crb is not only required for Ex tethering at the apical membrane but also for promoting its degradation via the SCFSlimb/β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase. Indeed, immediately downstream of its FERM domain, Ex contains a sequence that conforms to the D/S/TSGϕXS consensus sequence for canonical Slmb targets, which is conserved in Ex orthologs from arthropod species but absent from related FERM domain proteins such as Moe and Mer (43, 44) (Fig. S5 A and B). In addition, loss of Slmb increases Ex levels in vivo, whereas Slmb depletion prevents Crbintra-induced Ex degradation in cell culture (Figs. 5A and 6D). Thus, in crb mutants, Ex no longer reaches the apical membrane and is protected from degradation in the cytoplasm, where it accumulates but is presumably unable to repress Yki. When Crbintra is overexpressed, Ex turnover at the membrane (or in an endocytic compartment if Ex degradation occurs after Crb internalization) is accelerated, leading to its depletion and consequent Yki activation (Fig. 7). Therefore, in both cases, the outcome is Yki derepression, albeit for different reasons.

Fig. 7.

Model for Crb-mediated regulation of Ex function. Schematic model depicting molecular mechanisms used by Crb to regulate Ex function. See text for details.

How is the Slmb:Ex association regulated by Crb? Previous observations, along with our own results, point to the involvement of a phosphorylation-dependent degradation mechanism, because Crb induces Ex phosphorylation (17, 18) (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, mutation of the phosphodegron (Ser453) or the putative priming site (Ser462) leads to loss of Slmb:Ex association and Ex stabilization. The most obvious candidate Ex kinase in this context is aPKC, which is known to interact with the Crb polarity complex and to phosphorylate Crb at its FBM (3, 67, 68). However, aPKC is thought to be recruited to the Crb complex via Par-6, which interacts with Crb through the PBM at the C terminus of the Crb intracellular domain (67, 68). This is inconsistent with the fact that the PBM is dispensable for Crb to promote both Ex phosphorylation and degradation (17, 18) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, a dominant-negative version of aPKC is unable to rescue the overgrowth phenotype of Crbintra overexpression in the wing (18). The Hpo downstream kinase Wts is another attractive candidate, because mammalian LATS1/2 promotes YAP phosphorylation on Ser381, providing priming for phosphorylation by CK1δ/ε and triggering degradation by SCFβ-TrCP (69). However, neither Ser462 nor Ser453 conform to the Wts/LATS consensus. The identity of the kinases therefore remains open.

Regulation of tissue growth during development and adult life depends on the maintenance of tissue architecture, which, in turn, relies on cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (2). Due to its intimate coupling to polarity and cytoskeletal regulators, the Hpo signaling pathway is thought to sense epithelial integrity and couple tissue architecture to growth control (3, 4, 38). In particular, YAP has been shown to sense contact inhibition in cell culture, such that its progrowth activity is silenced as cultured epithelial cells reach confluence (70). This is thought to depend on the assembly of tight junctions, leading to repression of YAP by the mammalian Crb complex (19).

Recent work in flies and zebrafish has suggested that Crb can form homodimers in trans (11, 16, 71–73). This suggests that Crb mediates local cell–cell communication in epithelial tissues. Indeed, clonal loss of Crb leads to Crb depletion in the junctions of wild-type cells abutting the crb mutant tissue (11, 16, 71). This loss of Crb at the clone boundary is mirrored by loss of Ex, which is dependent on Crb for its apical localization (11, 16). Thus, loss of Crb caused by loss of polarity or cell death can be transmitted to neighboring cells. This has been proposed as a means of cell–cell communication to induce regenerative proliferation through Yki activation (3, 4, 38, 72). Indeed, genetic induction of epithelial wounds in imaginal discs has been shown to up-regulate Yki activity in cells neighboring the wound (74, 75). In addition, Yki/YAP is activated and promotes tissue regeneration upon injury in the vertebrate and fly intestine, as well as in the mouse liver (76–81).

These findings suggest that Crb (and perhaps other polarity proteins) functions as a sensor of cell density and tissue integrity during development. In this model, disruption of Crb function would lead to Yki/YAP derepression, which, upon tissue injury, would allow regenerative growth to ensue (3, 4). Another interesting question is whether liganded Crb behaves differently to unliganded Crb with respect to regulation of Ex stability. For example, it is possible that unliganded Crb promotes Ex turnover faster than its liganded counterpart, which might provide a sensitive means of responding to the status of neighboring cells. Further work will be needed to resolve this issue.

Our present work indicates that Crb fulfills a dual function in Hpo signaling, both recruiting Ex apically to repress Yki activity and promoting Ex turnover through phosphorylation and Slmb-dependent degradation. This mechanism could ensure constant turnover of Ex at the apical membrane, allowing Yki activity to rapidly respond to changing environmental conditions. This dynamic equilibrium could be particularly important to promote fast tissue regeneration upon injury.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Cell Culture and Expression Constructs.

Drosophila S2 cells were transfected with Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) and grown in Drosophila Schneider’s medium (Life Technologies) containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 50 μg/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Expression plasmids were generated using the Gateway technology (Life Technologies). ORFs were PCR amplified from cDNA (Drosphila Genomics Resource Center, https://dgrc.cgb.indiana.edu/vectors/Overview) and cloned into Entry vectors (pDONR207 and pDONR-Zeo). In-house designed expression vectors with V5 tag and vectors from the Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection (www.ciwemb.edu/labs/murphy/Gateway%20vectors.html) were used as destination vectors. All Entry vectors were sequence verified. Point mutations were generated using the Quickchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The SlmbΔF-box construct encodes a protein with an in-frame deletion of amino acids 92–136 of Slmb, created as previously described (47). The Ex full-length plasmid was previously described and the CrbMyc intra (Crbintra), CrbMyc intra ΔFBM (CrbΔFBM), and CrbMyc intra ΔPBM (CrbΔPBM) were kind gifts from D. Pan (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) (17, 31). The Moe-GFP, NTAN-FLAG, and HA-ubiquitin plasmids were kind gifts from B. Baum (University College London, London), M. Ditzel (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh), and P. Meier (Institute for Cancer Research, London), respectively.

RNAi Production and Treatment.

dsRNAs were synthesized using the Megascript T7 kit (Ambion). DNA templates for dsRNA synthesis were PCR amplified from genomic DNA or plasmids encoding the respective genes using primers that contained the 5′ T7 RNA polymerase-binding site sequence. The following primers were used: lacZ (Fwd –TTGCCGGGAAGCTAGAGTAA and Rev–GCCTTCCTGTTTTTGCTCAC); slmb (RNAi 1, Fwd–TGTACTGTAGGCAGGCGATG and Rev–AGGTGATCATCAGTGGCTCC); slmb (RNAi 2, Fwd–GCACAGGCCTTCACAACCACTATG and Rev–TTGCAGACCAGCTCGGATGATTT); and ago (Fwd–GGCTCCAAGTACGAGAGCAC and Rev–CAACTGCGATGAGGAGAACA). Following cell seeding, S2 cells were incubated with 15–20 μg dsRNA for 1 h in serum-free medium, before resupplementing with complete medium. RNAi-treated cells were lysed 72 h after dsRNA treatment and processed as detailed below.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis.

For FLAG immunoprecipitation assays, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 0.1 M NaF, phosphatase inhibitor mixtures 2 and 3 (Sigma), and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Cell extracts were spun at 17,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. FLAG-tagged proteins were purified using anti-FLAG M2 Affinity agarose gel (Sigma). After 1-h incubation at 4 °C, FLAG immunoprecipitates were washed three to four times with lysis buffer. Elution from beads was performed by incubating with 150 ng/μL 3× FLAG peptide for 15–30 min at 4 °C. For immunoprecipitation of ubiquitylated proteins, cells were collected by centrifugation and washed with cold PBS. Ten percent of cell material was lysed as for FLAG immunoprecipitation assays. The remaining 90% was lysed in boiling 1% SDS-PBS for 5 min. Following quick vortexing, samples were incubated at 100 °C for an additional 5 min before diluting fivefold using 0.5% BSA-1% Triton X-100–PBS. DNA was sheared by sonication and cell extracts were cleared at 17,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Samples were diluted twofold with 0.5% BSA-1% Triton X-100–PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C with monoclonal anti-HA agarose beads (Sigma) using Bio-Spin Columns (Bio-Rad). Columns were subsequently washed with 0.5% BSA-1% Triton X-100–PBS followed by a wash with 1% Triton X-100–PBS. HA immunoprecipitates were eluted from beads using 0.2 M glycine pH 2.5 for 30 min at room temperature (RT) and eluates were equilibrated with 1 M NH4HCO3. Detection of purified proteins and associated complexes was performed by immunoblot analysis using chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare or Thermo Scientific). Western blots were probed with mouse anti-FLAG (M2; Sigma), mouse anti-Myc (9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rat anti-HA (3F10; Roche Applied Science), mouse anti-V5 (Life Technologies), mouse anti-GFP (A-11120; Life Technologies), mouse anti-Crb (Cq4; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB), or mouse anti-tubulin (E7; DSHB).

Chemical Treatments.

For dephosphorylation assays, cell extracts were obtained in the absence of protein phosphatase inhibitors and cleared by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. A total of 50 μL of lysate sample was used in the assays. NaF and phosphatase inhibitor mixture 2 and 3 were added to mock samples. Fifty units of λ phosphatase (New England Biolabs) was added to λ phosphatase-treated samples. Mock and λ phosphatase-treated samples were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C before processing for immunoblot analysis. For proteasome inhibition experiments, cells were treated with 50 μM MG132 (Calbiochem) and 50 μM calpain inhibitor I (Ac-LLnL-CHO or LLnL) (Sigma) for 4 h before cell lysis or with 5 μM MG132 overnight. Where indicated, S2 cells were treated with 20 μM caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (Enzo Life Sciences) 1 h after transfection to prevent apoptosis.

Immunostaining.

Larval tissues were processed as previously described (31). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C unless otherwise stated. Mouse β-galactosidase (Promega) antibody was used at 1/500, rabbit Ex antibody (a kind gift from A. Laughon, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI) was used at 1/200, rat E-cad antibody (DCAD2; DSHB) was used at 1/20, mouse Crb antibody (Cq4; DSHB) was used at 1/10, rat Ci155 antibody (2A1; DSHB) was used at 1/200, and rabbit aPKC antibody (sc-216; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at 1/500. Anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-rat Rhodamine Red-X–conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch) anti-rat, anti-rabbit Cy5-conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were used at 1/500 and incubated for at least 2 h at room temperature. After washes, tissues were mounted in DAPI-containing Vectashield (Vector Labs). Fluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope (40× and 63× objective lenses). For Crb immunostaining, fly tissues were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA in PBS at RT for 30 min before serial washes with MeOH (30%, 50%, and 70% vol/vol) for 3 min each. Further steps including permeabilization were similar to the standard protocol with the exception of primary antibody incubation, which was performed at RT for at least 2 h.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis.

AP-MS experiments were performed using a GeLC MS/MS approach. Each gel lane was cut into eight equally sized gel pieces and subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion using a Perkin-Elmer Janus Automated Workstation. Peptide mixtures were acidified to 0.1% TFA and injected onto a nanoACQUITY UPLC (Waters Corporation) coupled to an LTQ-Orbitap XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific) via an Advion Biosciences Nanomate. Peptides were eluted over a 30-min gradient [5–40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile]. Peak lists were extracted using Mascot distiller and searched with Mascot v.2.4.1 (Matrix Science) against the Drosophila melanogaster Uniprot reference proteome. Oxidation of methionine was entered as a variable modification and the search tolerances were 5 ppm and 0.8 Da for peptides and fragments, respectively. Searches for each lane were combined and results compiled in Scaffold 4.0.3.

Protein Secondary Structure Predictions and Sequence Alignments.

Ex orthologs from different arthropod species were compiled with BLAST using the full-length Ex sequence as query. Sequence alignments were performed using MUSCLE and PRALINE (82, 83). Information on protein secondary structure predictions was obtained by running protein sequences through Phyre2 analysis (84). FERM domain structure nomenclature was based on the published structure of human Radixin (85). For identification of Slmb recognition sites, the Ex protein sequence was used as query in ScanProsite using the following sequence motifs taken from previously identified Slmb substrates: D-S-G-X(2,3)-S; K-X(8,15)-D-S-G-X-X-S; T-S-G-X-X-S; E-E-G-X-X-S; D-D-G-X-X-D; D-S-G-X-X-L; and D/S-S/T-Q/Y-X-X-S-T (43, 44, 86). Protein sequence accession numbers were as follows: NP_476840.2 (D. melanogaster Ex); XP_001988550.1 (Drosophila grimshawi Ex); XP_002052834.1 (Drosophila virilis Ex); EGI59916.1 (Acromyrmex echinatior Ex); XP_001842567.1 (Culex quinquefasciatus Ex); EHJ78777.1 (Danaus plexippus Ex); EFN85522.1 (Harpegnathos saltator Ex); XP_001604896.2 (Nasonia vitripennis Ex); XP_970685.1 (Tribolium castaneum Ex); NP_523413.1 (D. melanogaster Mer); NP_727290.1 (D. melanogaster Moe isoform B); and NP_609013.1 (D. melanogaster Pez isoform A).

Drosophila Genetics and Genotypes.

All crosses were raised at 25 °C with the exception of experiments where UAS-crbintra (26) was used, which were raised at 18 °C. Genotypes were as follows: hsFLP;; FRT 82B Ubi-GFP/FRT 82B (Figs. 1A and 6C); hsFLP;; FRT82B Ubi-GFP/FRT 82B crb82-04 (Fig. 1B); w; en-GAL4, UAS-CD8-GFP/UAS-CD8-GFP (Fig. 1C); w; en-GAL4, UAS-CD8-GFP/+; +/UAS-Crbintra (Fig. 1D); hsFLP;; FRT 82B Ubi-GFP/FRT 82B slmb1 (Fig. 6 D–F); hsFLP;; FRT82B arm-lacZ/FRT 82B crb11A22 (Fig. S1A); and hsFLP;; FRT82B Ubi-GFP/FRT 82B crb11A22 (Fig. S1 B and C).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Zhou for generating V5 tag Gateway destination expression vectors; B. Baum, M. Ditzel, and P. Meier for plasmids; P. Therond, D. Pan, G. Halder, D. Kalderon, E. Knust, and M. Milan for fly stocks; P. Jordan for microscopy support; T. Gilbank, S. Maloney, P. Moulder, and C. Gillen for support with fly genetics; F. Pichaud, B. Thompson, and Y. Zhou for comments on the manuscript; and L. Nemetschke for advice. Research in the N.T. laboratory is supported by Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315508111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Conlon I, Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell. 1999;96(2):235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin-Belmonte F, Perez-Moreno M. Epithelial cell polarity, stem cells and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(1):23–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genevet A, Tapon N. The Hippo pathway and apico-basal cell polarity. Biochem J. 2011;436(2):213–224. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroeder MC, Halder G. Regulation of the Hippo pathway by cell architecture and mechanical signals. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(7):803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong W, Guan KL. The YAP and TAZ transcription co-activators: Key downstream effectors of the mammalian Hippo pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(7):785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: Regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27(4):355–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont S, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474(7350):179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández BG, et al. Actin-capping protein and the Hippo pathway regulate F-actin and tissue growth in Drosophila. Development. 2011;138(11):2337–2346. doi: 10.1242/dev.063545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sansores-Garcia L, et al. Modulating F-actin organization induces organ growth by affecting the Hippo pathway. EMBO J. 2011;30(12):2325–2335. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wada K, Itoga K, Okano T, Yonemura S, Sasaki H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development. 2011;138(18):3907–3914. doi: 10.1242/dev.070987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CL, Schroeder MC, Kango-Singh M, Tao C, Halder G. Tumor suppression by cell competition through regulation of the Hippo pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(2):484–489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113882109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordenonsi M, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;147(4):759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2010;20(7):573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlegelmilch K, et al. Yap1 acts downstream of α-catenin to control epidermal proliferation. Cell. 2011;144(5):782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CL, et al. The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15810–15815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafezi Y, Bosch JA, Hariharan IK. Differences in levels of the transmembrane protein Crumbs can influence cell survival at clonal boundaries. Dev Biol. 2012;368(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling C, et al. The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10532–10537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004279107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Curr Biol. 2010;20(7):582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varelas X, et al. The Crumbs complex couples cell density sensing to Hippo-dependent control of the TGF-β-SMAD pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;19(6):831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tepass U, Theres C, Knust E. crumbs encodes an EGF-like protein expressed on apical membranes of Drosophila epithelial cells and required for organization of epithelia. Cell. 1990;61(5):787–799. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90189-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann A, Schneider M, Theilenberg E, Grawe F, Knust E. Drosophila Stardust is a partner of Crumbs in the control of epithelial cell polarity. Nature. 2001;414(6864):638–643. doi: 10.1038/414638a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong Y, Stronach B, Perrimon N, Jan LY, Jan YN. Drosophila Stardust interacts with Crumbs to control polarity of epithelia but not neuroblasts. Nature. 2001;414(6864):634–638. doi: 10.1038/414634a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krahn MP, Bückers J, Kastrup L, Wodarz A. Formation of a Bazooka-Stardust complex is essential for plasma membrane polarity in epithelia. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(5):751–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morais-de-Sá E, Mirouse V, St Johnston D. aPKC phosphorylation of Bazooka defines the apical/lateral border in Drosophila epithelial cells. Cell. 2010;141(3):509–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walther RF, Pichaud F. Crumbs/DaPKC-dependent apical exclusion of Bazooka promotes photoreceptor polarity remodeling. Curr Biol. 2010;20(12):1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wodarz A, Hinz U, Engelbert M, Knust E. Expression of crumbs confers apical character on plasma membrane domains of ectodermal epithelia of Drosophila. Cell. 1995;82(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laprise P, et al. The FERM protein Yurt is a negative regulatory component of the Crumbs complex that controls epithelial polarity and apical membrane size. Dev Cell. 2006;11(3):363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Médina E, et al. Crumbs interacts with moesin and beta(Heavy)-spectrin in the apical membrane skeleton of Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(5):941–951. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson EC, Pichaud F. Crumbs is required to achieve proper organ size control during Drosophila head development. Development. 2010;137(4):641–650. doi: 10.1242/dev.041913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumgartner R, Poernbacher I, Buser N, Hafen E, Stocker H. The WW domain protein Kibra acts upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, Tapon N. Kibra is a regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling network. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu J, et al. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badouel C, et al. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2009;16(3):411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Dev Biol. 2009;335(1):188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells CD, et al. A Rich1/Amot complex regulates the Cdc42 GTPase and apical-polarity proteins in epithelial cells. Cell. 2006;125(3):535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao B, et al. Angiomotin is a novel Hippo pathway component that inhibits YAP oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 2011;25(1):51–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.2000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu H, Bilder D. Endocytic control of epithelial polarity and proliferation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1232–1239. doi: 10.1038/ncb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laprise P. Emerging role for epithelial polarity proteins of the Crumbs family as potential tumor suppressors. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:868217. doi: 10.1155/2011/868217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Letizia A, Ricardo S, Moussian B, Martín N, Llimargas M. A functional role of the extracellular domain of Crumbs in cell architecture and apicobasal polarity. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 10):2157–2163. doi: 10.1242/jcs.122382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moleirinho S, Tilston-Lunel A, Angus L, Gunn-Moore F, Reynolds PA. The expanding family of FERM proteins. Biochem J. 2013;452(2):183–193. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poernbacher I, Baumgartner R, Marada SK, Edwards K, Stocker H. Drosophila Pez acts in Hippo signaling to restrict intestinal stem cell proliferation. Curr Biol. 2012;22(5):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tepass U. The apical polarity protein network in Drosophila epithelial cells: Regulation of polarity, junctions, morphogenesis, cell growth, and survival. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:655–685. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: Tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(6):438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS, Kumar KG. The many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: Reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(11):2028–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau AW, Fukushima H, Wei W. The Fbw7 and betaTRCP E3 ubiquitin ligases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2197–2212. doi: 10.2741/4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skaar JR, Pagan JK, Pagano M. Mechanisms and function of substrate recruitment by F-box proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(6):369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrm3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko HW, Jiang J, Edery I. Role for Slimb in the degradation of Drosophila Period protein phosphorylated by Doubletime. Nature. 2002;420(6916):673–678. doi: 10.1038/nature01272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuchs SY, Chen A, Xiong Y, Pan ZQ, Ronai Z. HOS, a human homolog of Slimb, forms an SCF complex with Skp1 and Cullin1 and targets the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of IkappaB and beta-catenin. Oncogene. 1999;18(12):2039–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hart M, et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr Biol. 1999;9(4):207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kitagawa M, et al. An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of beta-catenin. EMBO J. 1999;18(9):2401–2410. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroll M, et al. Inducible degradation of IkappaBalpha by the proteasome requires interaction with the F-box protein h-betaTrCP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(12):7941–7945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu C, et al. beta-Trcp couples beta-catenin phosphorylation-degradation and regulates Xenopus axis formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(11):6273–6278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shirane M, Hatakeyama S, Hattori K, Nakayama K, Nakayama K. Common pathway for the ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha, IkappaBbeta, and IkappaBepsilon mediated by the F-box protein FWD1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(40):28169–28174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer E, Jiang J, Chen ZJ. Signal-induced ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha by the F-box protein Slimb/beta-TrCP. Genes Dev. 1999;13(3):284–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki H, et al. In vivo and in vitro recruitment of an IkappaBalpha-ubiquitin ligase to IkappaBalpha phosphorylated by IKK, leading to ubiquitination. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256(1):121–126. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzuki H, et al. IkappaBalpha ubiquitination is catalyzed by an SCF-like complex containing Skp1, cullin-1, and two F-box/WD40-repeat proteins, betaTrCP1 and betaTrCP2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256(1):127–132. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vuillard L, Nicholson J, Hay RT. A complex containing betaTrCP recruits Cdc34 to catalyse ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha. FEBS Lett. 1999;455(3):311–314. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winston JT, et al. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13(3):270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu C, Ghosh S. beta-TrCP mediates the signal-induced ubiquitination of IkappaBbeta. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(42):29591–29594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yaron A, et al. Identification of the receptor component of the IkappaBalpha-ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 1998;396(6711):590–594. doi: 10.1038/25159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu G, et al. Structure of a beta-TrCP1-Skp1-beta-catenin complex: Destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF(beta-TrCP1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orlicky S, Tang X, Willems A, Tyers M, Sicheri F. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112(2):243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koepp DM, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2001;294(5540):173–177. doi: 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moberg KH, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. Archipelago regulates Cyclin E levels in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Nature. 2001;413(6853):311–316. doi: 10.1038/35095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stamos JL, Weis WI. The β-catenin destruction complex. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(1):a007898. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang J, Struhl G. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature. 1998;391(6666):493–496. doi: 10.1038/35154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kempkens O, et al. Computer modelling in combination with in vitro studies reveals similar binding affinities of Drosophila Crumbs for the PDZ domains of Stardust and DmPar-6. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(8):753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sotillos S, Díaz-Meco MT, Caminero E, Moscat J, Campuzano S. DaPKC-dependent phosphorylation of Crumbs is required for epithelial cell polarity in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(4):549–557. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP) Genes Dev. 2010;24(1):72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao B, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pellikka M, et al. Crumbs, the Drosophila homologue of human CRB1/RP12, is essential for photoreceptor morphogenesis. Nature. 2002;416(6877):143–149. doi: 10.1038/nature721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thompson BJ, Pichaud F, Röper K. Sticking together the Crumbs: An unexpected function for an old friend. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(5):307–314. doi: 10.1038/nrm3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zou J, Wang X, Wei X. Crb apical polarity proteins maintain zebrafish retinal cone mosaics via intercellular binding of their extracellular domains. Dev Cell. 2012;22(6):1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grusche FA, Degoutin JL, Richardson HE, Harvey KF. The Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway controls regenerative tissue growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2011;350(2):255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev Biol. 2011;350(1):139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bai H, et al. Yes-associated protein regulates the hepatic response after bile duct ligation. Hepatology. 2012;56(3):1097–1107. doi: 10.1002/hep.25769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cai J, et al. The Hippo signaling pathway restricts the oncogenic potential of an intestinal regeneration program. Genes Dev. 2010;24(21):2383–2388. doi: 10.1101/gad.1978810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karpowicz P, Perez J, Perrimon N. The Hippo tumor suppressor pathway regulates intestinal stem cell regeneration. Development. 2010;137(24):4135–4145. doi: 10.1242/dev.060483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ren F, et al. Hippo signaling regulates Drosophila intestine stem cell proliferation through multiple pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(49):21064–21069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012759107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shaw RL, et al. The Hippo pathway regulates intestinal stem cell proliferation during Drosophila adult midgut regeneration. Development. 2010;137(24):4147–4158. doi: 10.1242/dev.052506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Staley BK, Irvine KD. Warts and Yorkie mediate intestinal regeneration by influencing stem cell proliferation. Curr Biol. 2010;20(17):1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Simossis VA, Heringa J. PRALINE: A multiple sequence alignment toolbox that integrates homology-extended and secondary structure information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W289–W294. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: A case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(3):363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamada K, Shimizu T, Matsui T, Tsukita S, Hakoshima T. Structural basis of the membrane-targeting and unmasking mechanisms of the radixin FERM domain. EMBO J. 2000;19(17):4449–4462. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kanemori Y, Uto K, Sagata N. Beta-TrCP recognizes a previously undescribed nonphosphorylated destruction motif in Cdc25A and Cdc25B phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(18):6279–6284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.