Abstract

A wide variety of species, including vertebrate and invertebrates, consume food in bouts (i.e., meals). Decades of research suggest that different mechanisms regulate meal initiation (when to start eating) versus meal termination (how much to eat in a meal, also known as satiety). There is a very limited understanding of the mechanisms that regulate meal onset and the duration of the postprandial intermeal interval (ppIMI). In the present review, we examine issues involved in measuring meal onset and some of the limited available evidence regarding how it is regulated. Then, we describe our recent work indicating that dorsal hippocampal neurons inhibit meal onset during the ppIMI and describe the processes that may be involved in this. We also synthesize recent evidence, including evidence from our laboratory, suggesting that overeating impairs hippocampal functioning and that impaired hippocampal functioning, in turn, contributes to the development and/or maintenance of diet-induced obesity. Finally, we identify critical questions and challenges for future research investigating neural controls of meal onset.

Keywords: energy intake, hippocampus, meal onset, memory, obesity

a wide variety of species, including vertebrate and invertebrates, consume food in bouts (i.e., meals). Episodic food intake likely benefits survival in many ways. For instance, it prevents continuous exposure to harsh environments and increases flexibility in response to temporal variations in food availability. Decades of research suggest that different mechanisms regulate meal initiation (when to start eating) versus meal termination (how much to eat in a meal, also known as satiety). There is a very limited understanding of the mechanisms that regulate meal onset and the duration of the postprandial intermeal interval (ppIMI). The ppIMI is the time spanning from the end of one meal to the beginning of the next meal; it influences meal frequency and is thus a major determinant of food intake. As a result, a complete understanding of energy regulation must take into account the neural factors that regulate meal onset. Not only will this fill a critical void in our basic understanding of energy regulation, but understanding controls of meal onset will also likely advance our knowledge of the causes of snacking, excess caloric intake and obesity. In the present review, we discuss issues involved in measuring meal onset and some of the limited available evidence regarding how it is regulated. Then, we review evidence implicating the hippocampus in energy regulation, describe our recent work indicating that dorsal hippocampal neurons inhibit meal onset during the ppIMI and discuss the processes that may be involved in this. We also synthesize recent evidence, including evidence from our laboratory, suggesting that overeating impairs hippocampal functioning and that impaired hippocampal functioning, in turn, contributes to the development and/or maintenance of diet-induced obesity. Finally, we identify critical questions and challenges for future research investigating neural controls of meal onset.

How Is Meal Onset Measured?

The majority of studies examining neural controls of food intake measures meal size, cumulative intake, or total amount consumed within a certain period of time. In contrast, very few studies actually measure the interval between two meals (i.e., the ppIMI). There are instances where experimenters do measure latency to eat, but this measure is most relevant to the ppIMI if it is latency since the last meal was terminated rather than latency to eat after an experimental manipulation. Other measures related to meal onset and the ppIMI include the satiety ratio, which is the duration of the ppIMI divided by the size of the preceding meal, and the postprandial correlation, which describes the positive association between the size of a meal and the length of time that passes before the next meal is initiated.

An important consideration for measuring meal onset and the ppIMI is the way in which the end of a meal is operationally defined. This is not straightforward, as there is a need to discriminate intrameal pauses from those that signal the end of a meal. How the end of a meal is defined influences how many meals are measured during an experimental period, as well as meal size and duration (212, 238). In rats, a survey of the literature reveals that the criterion used to define the end of a meal ranges from 1 to 40 consecutive minutes without food intake (see Refs. 29, 30, 63, 79, 84, 233). Some investigators define the end of a meal with behavioral parameters, such as grooming and sleeping (5, 49, 131, 132), and others use mathematically based definitions such as log-survivorship analysis (29, 63, 84). This inconsistency in the operational definitions of meal termination makes comparisons across studies difficult. This may be why, for instance, some researchers observe a significant postprandial correlation (62, 136, 238), whereas others do not (29, 135).

Converging evidence suggests that one of the most valid criteria to define meal termination in rats is five consecutive minutes without eating. Once a rat has stopped eating for 5 min there is a very low probability that the rat will initiate eating; the longer the criterion, the greater the probability of eating (77, 238). In addition, a significant postprandial correlation is observed when this operational definition is used (238). Moreover, this 5-min criterion is associated with the expression of the behavioral satiety sequence in rats (5, 77, 132), which is an increase in grooming and locomotor activity (e.g., sniffing and rearing) following a meal that eventually terminates with resting behavior (5, 21, 132, 186, 216, 238).

What Do We Know About the Factors That Influence Meal Initiation?

To date, evidence suggests that internal signals generated by a previous meal, and environmental and conditioned stimuli interact to influence meal onset.

Internal signals influence meal onset.

As noted above, under certain conditions, there is a positive relation between the size of a meal and the timing of the next meal. This suggests that internal signals generated by an eating episode influence meal onset (42, 127, 213, 215). This interpretation is supported, for example, by the finding that there is a small and transient decrease in plasma glucose concentrations ∼5 min prior to meal onset in free-feeding rats (24, 25, 141, 201). In addition, decreases in activity-independent metabolism (160) and increases in brown adipose tissue thermogenesis have been observed during the period before eating is initiated (19, 126). Levels of the peripheral gut peptide ghrelin peak prior to meal onset (46) and administering hormones associated with hunger, such as ghrelin, increase meal frequency in rats (33, 46, 75).

Environmental and conditioned stimuli influence meal onset.

Not surprisingly, endogenous biological clocks participate in meal timing. Lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN; the primary circadian timing mechanism in the brain) disrupt meal patterning such that SCN-lesioned rats eat an equal number of meals throughout the day and night (118, 158, 161, 209). Non-SCN food-entrainable endogenous oscillators also influence meal onset. Rats placed on a feeding schedule determined by the investigator come to display anticipatory changes in behavior and in a multitude of physiological responses during the period preceding the scheduled meal (68, 194, 207, 219). For instance, cephalic levels of glucagon-like peptide-1, ghrelin, and insulin peak ∼1 h, 30 min, and 10 to 15 min preceding a meal, respectively (14). Such conditioned anticipatory responses are presumed to prepare the animal metabolically for the forthcoming meal (234). Food-entrainable oscillators are likely independent of the SCN because SCN lesions do not prevent these anticipatory responses (129, 204–206, 214). Rather, food-entrainable oscillators are likely located in peripheral tissues, such as liver and pancreas (48, 110, 208).

Learned associations between environmental cues and food availability can override satiety cues and stimulate ingestion. For example, the cues or context associated with palatable food will cause a sated rodent or human to eat (43, 177, 184, 194, 228, 229). In rats, this cue-induced increase persists for several hours after the onset of the cue and is the result of associative learning, rather than a nonspecific effect of environmental or food-related novelty (184). Lesions of the basolateral amygdala (99, 100) or medial prefrontal cortex (177) prevent cue- and context-potentiated feeding of food pellets, respectively, suggesting that these areas mediate the effect of learned associations between environmental cues and food availability on meal initiation. The basolateral amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex likely mediate these effects via a direct influence on the lateral hypothalamus. Conditioned cues that stimulate eating in sated rats activate neurons in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex that project directly to the lateral hypothalamus (176), and lesions that functionally disconnect the basolateral amygdala from the lateral hypothalamus abolish cue-potentiated feeding (176, 178). These conditioned cues likely act by stimulating orexin (ORX)/hypocretin hypothalamic neurons because a cue associated with food selectively increases c-Fos levels in hypothalamic ORX neurons, but not in neurons containing melanin-concentrating hormone (175). It is worth noting, though, that there do not appear to be any neural studies that have measured the effects of a conditioned cue on the duration of the ppIMI; rather, these studies typically measure the amount that sated animals will eat when a conditioned cue is presented (e.g., 176–178). Also, there does not seem to be any evidence indicating that rats exposed to conditioned food-related cues gain more weight than unexposed controls (108, 174).

How does cognition influence the decision to start eating?

A critical question in neuroscience that is very poorly addressed is, “How do cognitive processes modulate energy intake?” The majority of research on meal onset either ignores the contribution of cognitive processes, or acknowledges a likely role, but provides no direct evidence (e.g., 17, 199, 237). As such, current theories of meal onset are unsatisfactory and incomplete, because they do not account for the fact that many animals use conscious cognition to guide behavior. Conscious cognitive processes increase behavioral flexibility, thereby enhancing an animal's ability to adapt to changes within and between environments. In terms of cognitive processes, we hypothesize more specifically that an animal's hippocampal-dependent memory of when it last ate influences the timing of its next meal. In other words, we propose that the question: “When should I eat again?” is answered in part by “When did I last eat?”

Why the Hippocampus?

Hippocampal neurons form episodic memories.

The hippocampal formation (henceforth referred to as the “hippocampus”) is composed of the dentate gyrus, three fields (CA3, CA1, and CA2), and the subiculum (231). A critical function of hippocampal neurons is to represent episodic (autobiographical) memories (71, 197, 224). Such memories tell an animal what, where, and when something occurred in its life (156) and serve to guide goal-directed behavior (117, 197, 203). Compared with other kinds of memory (e.g., implicit, procedural, and classical, and operant conditioning), episodic memory is more accessible to awareness (i.e., conscious), even in nonhuman animals (70, 200). Evidence suggests that hippocampal neurons are involved in the active maintenance of episodic memories, as well as the formation of long-term episodic memories (66, 69, 230). Along the septotemporal axis, the hippocampus can be divided into dorsal and ventral regions (157). Dorsal hippocampal neurons appear to be preferentially involved in learning and memory and spatial navigation, whereas ventral hippocampal neurons participate in emotional and affective processes (11, 72, 130, 157).

The hippocampus is anatomically poised to regulate meal onset.

Although the hippocampus is primarily associated with memory, it is striking how it is equipped neuroanatomically and neurochemically to influence energy intake. Hippocampal neurons receive neural signals regarding food stimuli from the arcuate nucleus, nucleus of the solitary tract (oropharyngeal, stomach, small intestine), insula (internal perception of hunger), and orbitofrontal cortex (taste) (4, 104, 187, 202, 226, 227). In addition, throughout the hippocampus there is a multitude of receptors for preprandial and postprandial signals, including leptin (long/signaling variant) (151), insulin, ghrelin, glucose, cholecystokinin (CCK; likely CCK-B) (1, 196, 222), glucocorticoids, neuropetide Y, bombesin (neuromedin B, gastrin-releasing peptide receptor and bombesin-like receptor 3) (13, 101, 107, 111, 232), and galanin (134). Hippocampal neurons project to all brain areas critical to energy intake. More specifically, hippocampal neurons send extensive efferent projections to the hypothalamus (31, 124), the brain region most traditionally associated with energy regulation (20, 67, 192). These projections terminate in several hypothalamic regions, including anterior hypothalamic nucleus, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, lateral hypothalamic and lateral preoptic areas, and medial preoptic area. Hippocampal neurons also project to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (45, 182), nucleus accumbens (22, 86) and lateral septum (31), which also influence ingestive behavior (36, 122, 143, 164, 195, 211). It is possible that hippocampal neurons regulate homeostatic controls of intake via projections to hypothalamus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and/or lateral septum and hedonic controls via nucleus accumbens.

Food-related hormones and adipokines influence hippocampal function.

Many food-related hormones and cell-signaling proteins released by adipose tissue (i.e., adipokines) enhance hippocampal mnemonic function. For example, administration of ghrelin or leptin facilitates neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus region (82, 154). Peripheral and intrahippocampal injections of ghrelin increase hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spine density (27, 34, 65). Moreover, peripheral and/or intra-hippocampal injections of leptin, insulin, and ghrelin enhance hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in a variety of memory tasks (8, 9, 26, 28, 34, 44, 65, 73, 83, 149, 155, 166).

Limited evidence suggests that some food-related signals influence energy intake, in part, via effects on hippocampal neurons. Hippocampal infusions of the hunger-stimulating hormone ghrelin increase the amount of food consumed and meal frequency (26, 28, 114). In contrast, intrahippocampal infusions of the anorexic signal leptin suppress food intake and decrease body weight (115). The finding that intrahippocampal leptin infusions impair the expression of a conditioned place preference for food suggests that hippocampal leptin may have also a role in food-related memory processing (115). Collectively, these findings suggest that during the period following a meal, hippocampal neurons are in an optimal state to influence memory. Traditionally, the thinking has been that these memories are created in the service of food procurement (e.g., remembering the location of a food source and where food was consumed; 39, 47, 76, 80, 88, 109, 138, 165). We propose that such memories also serve to regulate the duration of the ppIMI and, thus, the timing of meals.

Hippocampal lesions impair energy regulation.

The findings of lesion studies suggest that the hippocampus plays an inhibitory role in energy intake. For instance, in rodents, hippocampal lesions increase food intake and promote weight gain (51). In rats, lesions of the fimbria fornix (major hippocampal input/output pathway) or hippocampus increase meal frequency (40, 55, 167), suggesting that hippocampal neurons may inhibit meal onset by extending the ppIMI. Hippocampal lesions also impair the development of a learned taste aversion when there is a long interval between taste exposure and the induction of malaise (125). Interestingly, humans and rodents with hippocampal deficits are impaired in their ability to identify whether they are sated or hungry (81, 90, 94, 191). In rodents, this is demonstrated by a hippocampal lesion-induced deficit in the ability to use interoceptive cues to guide behavior (55, 56, 96). The famous patient H.M. and other humans with hippocampal-dependent episodic memory deficits have difficulties determining whether they are sated, do not remember eating, and will eat an additional meal when presented with food, even if they have just eaten to satiety (81, 90, 94, 191).

Reversible inactivation of dorsal hippocampal neurons during the postprandial period accelerates meal onset.

On the basis of the evidence reviewed above, our overarching hypothesis is that hippocampal neurons form a memory of a meal and use this information to temporarily inhibit meal onset during the ppIMI. As a first step toward testing this hypothesis, we determined whether temporarily disrupting dorsal hippocampal function during the period following a meal would accelerate meal onset (91). We elected to restrict our manipulation to the dorsal hippocampal region, given its prominent role in episodic memory (12, 97, 120, 137, 145, 181). Inactivating hippocampal activity after a meal and using a reversible lesion is a powerful strategy for investigating the controls of meal onset. This approach extends previous studies by restricting the manipulations to the ppIMI, thereby avoiding effects on the size of the preinfusion meal and allowing us to study meal onset separately from satiety. This critical dissociation between satiety and meal onset is not possible with permanent lesions. From a memory viewpoint, the manipulations are confined primarily to the consolidation period (i.e., the postlearning period when memories are being strengthened and stabilized). Moreover, the use of reversible inactivation minimizes the possible contribution of other changes associated with surgery and lesions, such as neural reorganization and compensation, or weight loss (51).

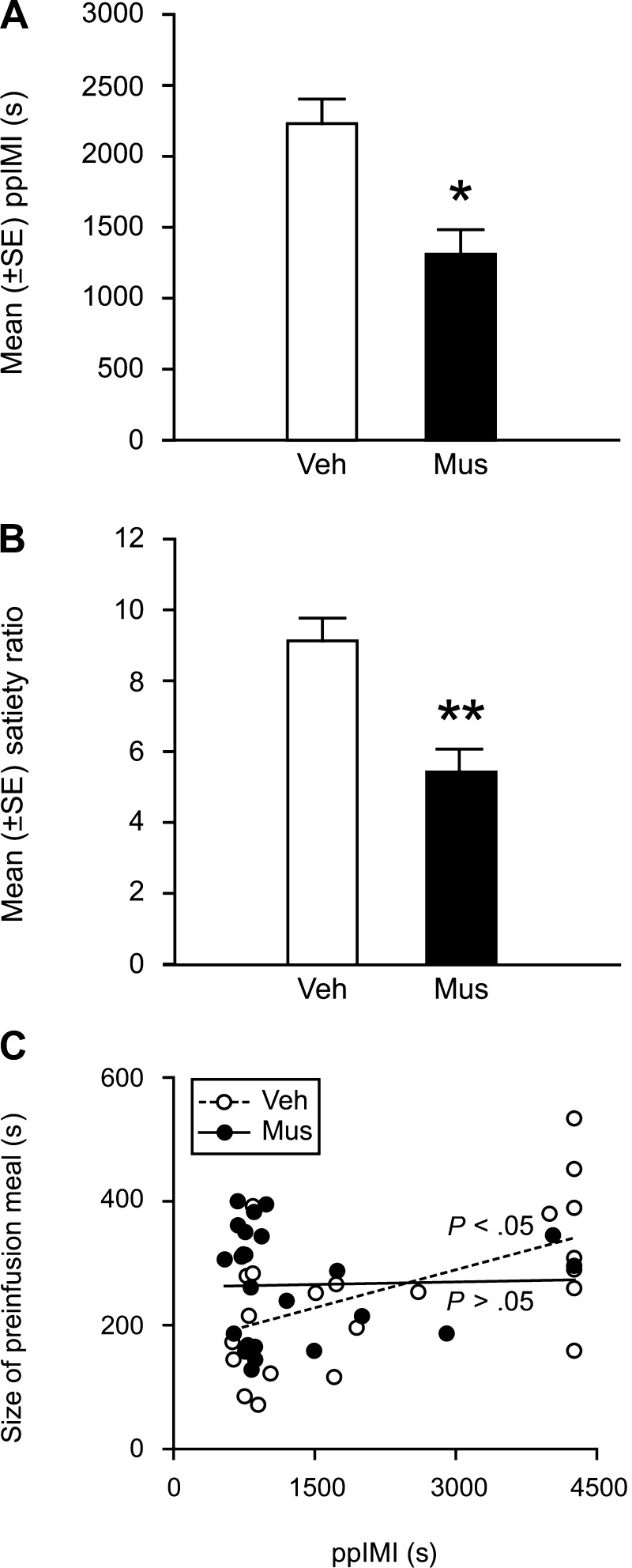

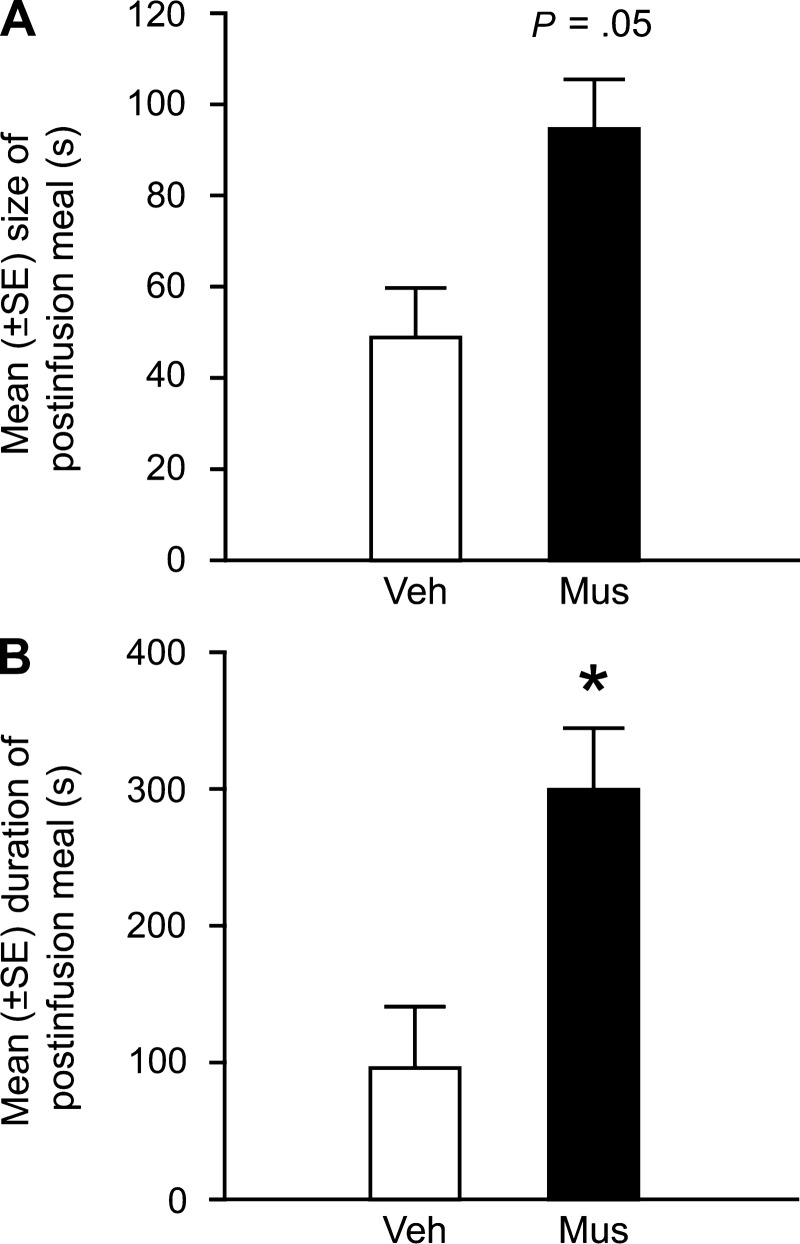

In this study, rats were trained to consume a sucrose solution at a scheduled time daily. We elected to use the sucrose solution as the meal because 1) it is palatable, 2) its stimulus qualities are specific, 3) its peripheral and central processing sites and mechanisms have been identified, 4) its concentration can be varied to manipulate postingestive consequences (61, 123, 225), and 5) it cannot be hoarded. Importantly, we kept the time and location in which rats consumed the sucrose solution constant to minimize the contribution of novelty, spatial, contextual or circadian processes. On the experimental day, we infused the GABA-A receptor agonist muscimol into the dorsal hippocampus after the rats had finished their sucrose meal, which was operationally defined as five consecutive minutes without contacting the sipper tube (221, 238). Our findings show that inactivating dorsal hippocampal neurons during the postprandial period significantly decreased the duration of the ppIMI, decreased the satiety ratio and abolished the postprandial correlation (see Fig. 1, A–C). These inactivation-induced changes do not appear to be due to a stimulatory effect of the reversible lesions on activity because the inactivation did not increase speed of consumption. Interestingly, the inactivation also increased the size and duration of the postinfusion meal (see Fig. 2), suggesting that dorsal hippocampal neurons may also influence satiety. Given that centrally infused muscimol can inhibit neural activity for several hours (7, 147), neural activity was likely still disrupted during the consumption of the postinfusion meal. One possibility is that the muscimol-induced increase in meal size may be the consequence of increased positive feedback from the ingested food, decreased negative feedback, or both.

Fig. 1.

Reversible inactivation of dorsal hippocampal neurons with muscimol (Mus) during the postprandial period decreases the duration of the postprandial intermeal interval (ppIMI; A), decreases the satiety ratio (duration of the ppIMI/size of the preceding meal) (B), and prevents the postprandial correlation (positive association between the size of a meal and the length of time before the next meal is initiated) (C). *P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 vs. vehicle (Veh) infusions. Adapted with permission from Ref. 91 [Henderson, Y.O., Smith, G. P., and Parent, M. B., Hippocampus, Hippocampal neurons inhibit meal onset. 23: 100–107, 2013 (doi: 10.1002/hipo.22062)].

Fig. 2.

Reversible inactivation of dorsal hippocampal neurons with muscimol during the postprandial period increases the postinfusion meal size (A) and increases the duration of the postinfusion meal (B). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle infusions. Adapted with permission from Ref. 91 [Henderson, Y.O., Smith, G. P., and Parent, M. B., Hippocampus, Hippocampal neurons inhibit meal onset. 23: 100–107, 2013 (doi: 10.1002/hipo.22062)].

What Processes Are Involved in Hippocampal Inhibition of Meal Onset?

Is formation of an episodic memory necessary?

Our findings with reversible inactivation of dorsal hippocampal neurons during the ppIMI support our working hypothesis that dorsal hippocampal neurons form a memory of a meal and delay meal initiation during the postprandial period. The fact that the inactivation was timed to occur during the period immediately following the end of meal means that these neurons were inactivated during the consolidation period when the memory of the meal was being formed. This interpretation is consistent with extensive evidence indicating that hippocampal neurons encode episodic autobiographical memories (71, 197) and that posttraining reversible inactivation of dorsal hippocampal neurons impairs consolidation of other types of memory: place avoidance memory (38, 140), object-place recognition memory (163), and spatial water maze (37, 98). Our data add to the growing body of evidence indicating that dorsal hippocampal neurons are involved in more than just spatial types of memory (41, 87, 121, 171). In addition to memory formation, it is likely that memory retrieval is also important for delaying meal onset (60), which could be tested by inactivating dorsal hippocampal neurons during the period immediately preceding the next meal.

Our results and interpretations are also congruent with findings obtained in humans with temporal lobe amnesia that includes damage to the hippocampus. As noted above, individuals with temporal lobe amnesia have little or no declarative recollection of having eaten a meal (90, 94, 191). These findings are also consistent with research in humans showing that manipulating cognition, such as what time participants think it is or how many calories they think they have consumed, influences food intake (23, 32, 193, 198, 235). Manipulating memory, in particular, in humans also influences food intake. More specifically, enhancing memory for the specific attributes of a recently eaten meal inhibits the amount of food that is subsequently ingested (92, 93); in contrast, impairing encoding of a meal with distraction increases later food intake (95, 153). To the best of our knowledge, however, it is not known yet whether manipulating memory in human participants influences the duration of the ppIMI in addition to the amount consumed.

Do hippocampal neurons track time to regulate meal onset?

Hippocampal inactivation may accelerate meal onset by interfering with the ability of hippocampal neurons to track time since the last meal. Several converging lines of evidence indicate that hippocampal neurons are involved in interval timing. For instance, electrophysiological recordings have revealed the presence of a significant number of hippocampal neurons that encode and maintain temporal information (64, 105, 128, 142, 145, 159). These “time cells” contribute to remembering the order of events and bridge the gap between discontiguous events (142, 159). Similarly, neuroimaging studies in human participants demonstrate that hippocampal activity is associated with successful encoding of temporal memories (106, 223). It may not be surprising, then, that lesions of the hippocampus or its major input and output projections (i.e., fimbria fornix or medial septal area) disrupt both working and reference temporal memories (reviewed in Ref. 150). As in the case of our finding that hippocampal inactivation accelerates meal onset (91), rats with impaired hippocampal functioning display leftward shifts in their timing functions, such that they remember the timing of reinforcement as having occurred earlier than it did. A similar phenomenon is observed in humans with damage to the medial temporal lobes (reviewed in Ref. 150). Interestingly, patient H. M. who displayed episodic memory deficits and increased meal frequency, also consistently underestimated the passage of time for intervals greater than 20 s. His estimates were proportional to the square root of the actual interval plus 20 s, suggesting that an hour in our time felt like 3 min to him (185). More recent studies indicate that selective lesions of dorsal hippocampal neurons also produce these leftward shifts in interval timing (217, 218). In terms of subfields, area CA1 appears to be necessary for the coding of temporal aspects of episodic memories, whereas the dentate gyrus and CA3 region appear to be less essential (12, 97, 119, 137). We speculate that using timing mechanisms to control meal intervals may be more adaptive than relying solely on physiological hunger because such a mechanism would allow for anticipatory responses (e.g., procuring food in preparation for hunger).

Do hippocampal neurons inhibit memory to influence onset?

Using permanent hippocampal lesions, Davidson and colleagues have played a pivotal role in demonstrating that memory and hippocampal neurons influence energy regulation (16, 53, 54, 56–58, 113). They propose that internal satiety cues activate hippocampal neurons, which, in turn, inhibit the ability of environmental cues and memories of the reinforcing effects of eating to stimulate additional eating. This function is assumed to reflect the more general role of hippocampal neurons in negative occasion setting and inhibition of behavior and memory (58). Collectively, their findings raise the possibility that hippocampal neurons delay meal onset by inhibiting memory of the satiating and rewarding postingestive consequences of a meal (16, 51, 56–58, 113).

Do Dorsal and/or Ventral Hippocampal Neurons Influence Meal Onset?

Several lines of evidence support the involvement of dorsal hippocampus in regulating the ppIMI. Dorsal hippocampal neurons are primarily involved in episodic memory (12, 97, 120, 137, 145, 181), inactivation of these neurons during the ppIMI accelerates meal onset (91), rats with dorsal hippocampal lesions are impaired in a task that involves learning to associate internal energy states with shocks (96), and dorsal hippocampal neurons are implicated in tracking elapsed time (217, 218). Yet, there are compelling reasons to hypothesize that ventral hippocampal neurons should also be involved in regulating meal onset. Selective lesions of the ventral pole of the hippocampus increase energy intake and body mass (51), and ventral hippocampal lesions also impair the ability to learn to associate internal energy states with shocks (96). Moreover, ventral hippocampal neurons are involved in memory that has an emotional or affective component (103, 146), suggesting that these neurons could be involved in the memory of food. This is supported by the finding that infusions of leptin into the ventral hippocampus (but not dorsal hippocampus) impair the expression of a conditioned place preference for a context previously associated with food (115). Infusions of ghrelin into ventral hippocampus, but not dorsal hippocampus, increase cumulative chow intake, and ventral hippocampal infusions of ghrelin also increase meal frequency, meal size, and cue-induced eating (114). Finally, ventral hippocampus neurons are the primary output area of the hippocampus to brain areas involved in eating, including hypothalamus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, lateral septum, and nucleus accumbens (22, 31, 86).

Is Impaired Hippocampal Function a Cause and Consequence of Diet-Induced Obesity?

Currently, more than one-third of the adult population in the United States is considered obese (162). This epidemic persists despite decades of research into the causes and treatment of obesity. One of the obstacles may be that investigative efforts have concentrated heavily on the hypothalamus and related signals. The evidence reviewed above raises the possibility that altered hippocampal function may contribute to either the development of diet-induced obesity or the maintenance of the obese state. This is significant, because a variety of illnesses and stressors are associated with altered hippocampal structure and function. These include, for instance, mental illness (e.g., mood disorders and schizophrenia; reviewed in Refs. 35, 78, 173, and 180), childhood abuse, and posttraumatic stress disorder (reviewed in Refs. 89 and 102), chronic stress (reviewed in Ref. 148), chronic illnesses such as diabetes (reviewed in Refs. 133 and 183) and fibromyalgia (reviewed in Ref. 6), alcohol withdrawal (reviewed in Ref. 144), and normal aging (reviewed in Ref. 18). For instance, we recently discovered that neonatal inflammatory pain, such as that experienced in the treatment of premature birth, produces persistent hippocampal-dependent memory deficits in adulthood (169).

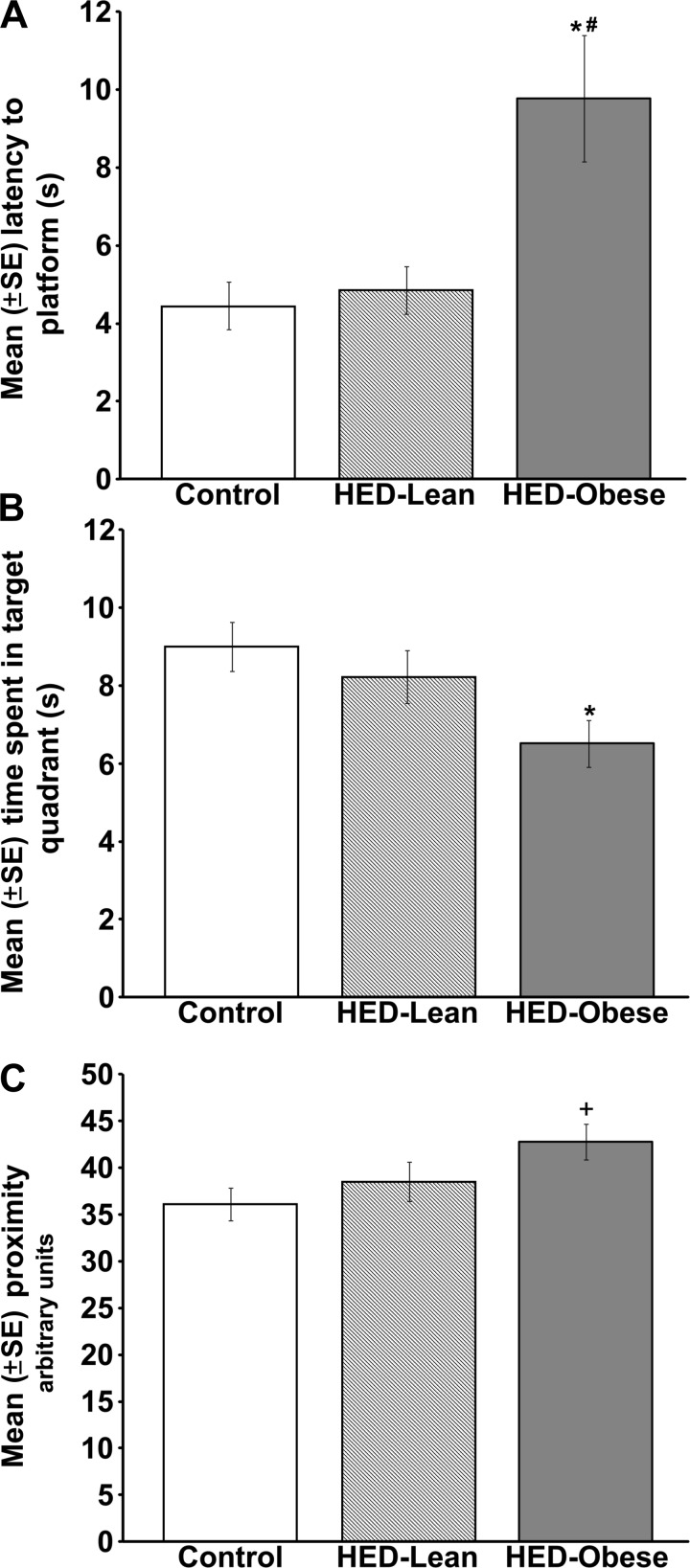

Perhaps more germane to the present discussion is the fact that excess intake of nutrients impairs hippocampal structure and function. That is, there is a wealth of evidence showing that overeating causes hippocampal pathology. We and others have shown that feeding rodents high-energy diets impairs hippocampal-dependent memory (15, 50, 53, 59, 74, 85, 113, 172, 188, 189, 210). As an example, we have demonstrated that rats fed high-energy diets have significant hippocampal-dependent memory deficits in the spatial water maze (50, 188, 189). The spatial water maze task is the most widely used and accepted test of hippocampal-dependent memory in rats (220). In this task, rats are trained to use cues in a room to locate a submerged platform in a water-filled pool. Latency to swim to the platform across training trials is used as a measure of learning. Memory is typically tested 1 or 2 days later by placing the rats in the pool with the platform absent and measuring latency to swim to the previous platform location, the amount of time spent in the area where the platform was located previously (i.e., the target quadrant), and average distance from the platform (i.e., average proximity). In a recent study, we gave male rats choices of standard chow, tap water, a 32% sucrose solution, and animal lard and used a tertile split to divide these rats based on the percent change in body mass during the first 5 days on the diet (50). Rats in the bottom 33% (i.e., those with the least percent change in body mass) were defined as high-energy diet lean rats (HED-Lean) and those in the top tertile were labeled high-energy diet obese (HED-Obese). Eight weeks later, the HED-Obese rats, but not the HED-lean rats were impaired on the water maze retention test. More specifically, compared with standard chow-fed control rats, HED-Obese rats had longer latencies to reach the platform location (Fig. 3A), spent less time in the target quadrant (Fig. 3B), and swam further away from the platform location (Fig. 3C). Of note, swimming speed did not differ between the groups. Interestingly, these impairing effects of the HED diet were restricted to the memory test because the HED-Obese rats did not have any difficulties learning the platform location during training. That is, latency to swim to the platform during training decreased comparably in control and high-energy diet-fed rats. These findings are similar to those by Davidson et al. (52, 59) showing that a high-energy diet impairs nonspatial hippocampal-dependent memory in diet-induced obese rats, but not in diet-resistant rats. Our recent findings indicate further that consumption of a high-fat/high-sucrose cafeteria diet also prevents the memory-enhancing effects of emotional arousal in a hippocampal-dependent object location memory task (190). In human participants, higher self-reports of fat and sugar intake are correlated with hippocampal-dependent memory deficits and impaired recall of a recently eaten meal (81).

Fig. 3.

Rats that gain the most body mass during the first 5 days on a high-energy cafeteria style diet (HED-Obese) are impaired 8 wk later on a hippocampal-dependent memory test. Rats that gain the least amount of weight during the first 5 days (i.e., HED-Lean) do not develop memory deficits. On the memory test, HED-Obese rats had longer latencies to reach the platform location (A), spent less time in the target quadrant (B), and swam further away from the platform location (C) *P < 0.05 vs. standard chow controls; #P < 0.05 vs. HED-Lean; +P < 0.05 vs. standard chow controls; main effect P = 0.053. Adapted with permission from Ref. 50 [Darling, J. N., Ross, A. P., Bartness, T. J., and Parent, M. B., Obesity (Silver Spring), Predicting the effects of a high-energy diet on fatty liver and hippocampal-dependent memory in male rats. 21: 910–917, 2013 (doi: 10.1002/oby.20167)].

In rodents, high-energy diets also decrease hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (116, 236), synaptic plasticity (152, 210), and neurogenesis (139, 170). These pathological effects of high-energy diets on hippocampal function are likely mediated by a number of processes, including neuroinflammation (168, 179), oxidative stress (2, 3, 74), altered blood-brain barrier permeability (10, 53, 168), and hippocampal insulin resistance (152).

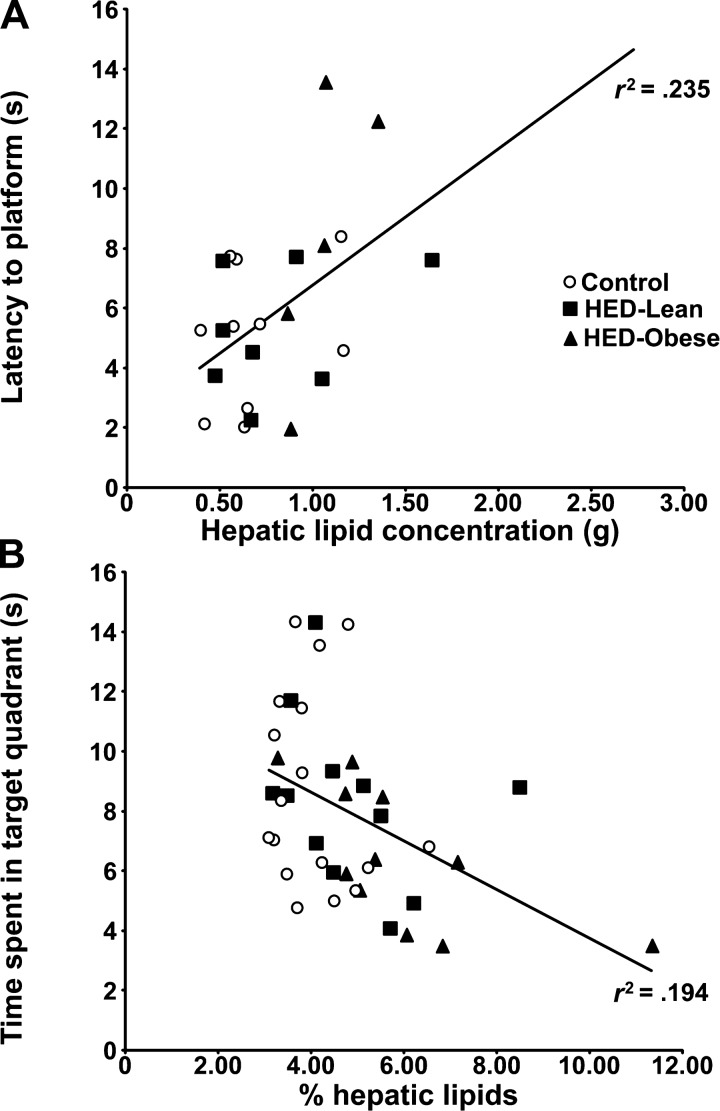

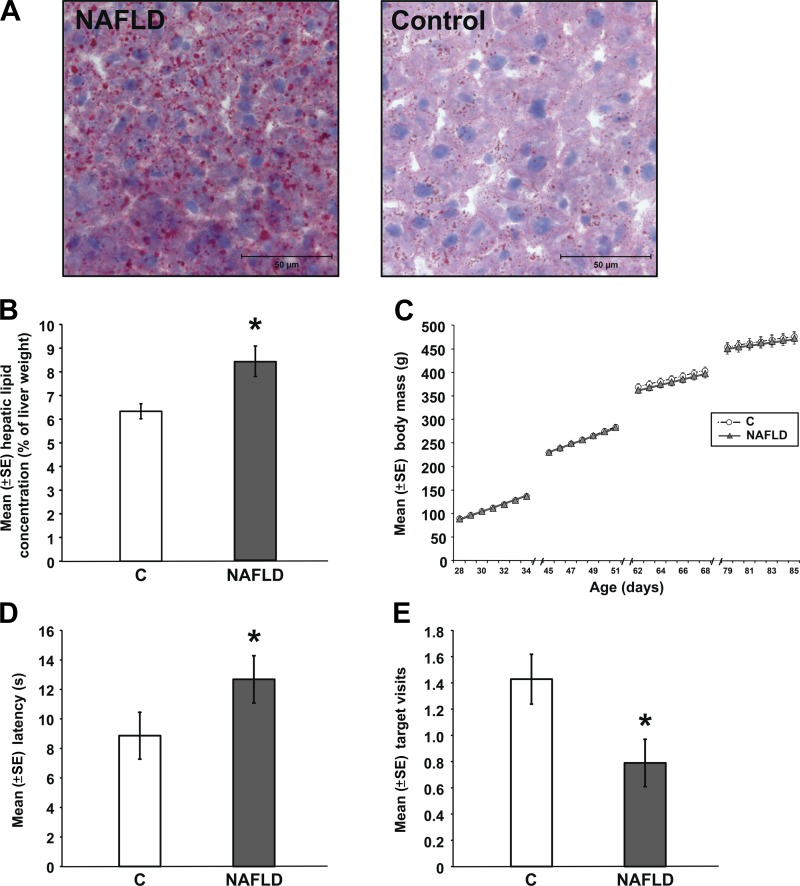

Collectively, our findings indicate that the memory-impairing effects of high-energy diets are associated with increased liver mass and elevated liver lipids, rather than with elevations in body mass, plasma triglyceride, insulin, or glucose concentrations (50, 188, 189). For instance, the amount of fat in the liver correlates inversely with performance on memory tests (e.g., Fig. 4). Also, we have found that feeding rats a 60% fructose diet, which is a commonly used animal model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), impairs spatial water maze retention performance but does not increase body mass (see Fig. 5) (188, 189).

Fig. 4.

The effects of high-energy diets on memory are modestly but significantly correlated with the effects of the diets on hepatic liver lipid concentrations (P < 0.05). Adapted with permission from Ref. 50 [Darling, J. N., Ross, A. P., Bartness, T. J., and Parent, M. B., Obesity (Silver Spring), Predicting the effects of a high-energy diet on fatty liver and hippocampal-dependent memory in male rats. 21: 910–917, 2013 (doi: 10.1002/oby.20167)].

Fig. 5.

The memory-impairing effects of high-energy diets are associated with elevated liver lipids rather than elevated body mass. Rats fed a 60% fructose diet for 12 wk meet the human diagnostic criterion for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver sections stained with hematoxylin and oil red-O reveal that NAFLD rats have larger and more numerous lipid droplets than control rats (A), have higher hepatic lipid concentrations (B), but do not have increased body mass (C). NAFLD rats display impaired memory on the hippocampal-dependent spatial water maze task, including longer latencies to reach the location where the platform was previously located (D) and fewer visits to the previous platform location (E) (*P < 0.05 vs. Control). Adapted with permission from Ref. 189 [Reprinted from Physiology and Behavior 106, Ross, A. P., Bruggeman, E. C., Kasumu, A. W., Mielke, J. G., and Parent, M. B., Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease impairs hippocampal-dependent memory in male rats, 133–141, 2012, with permission from Elsevier].

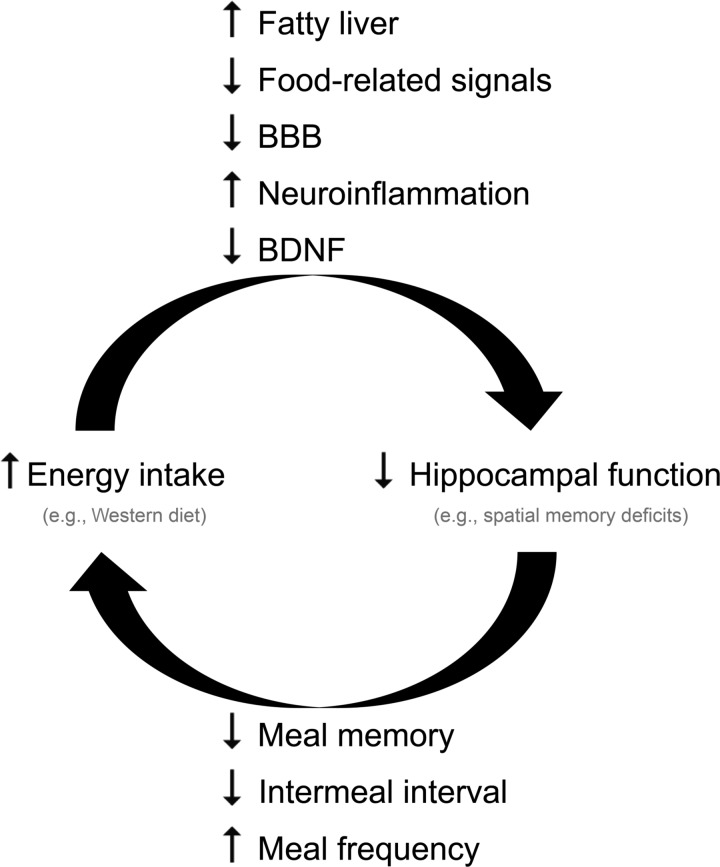

Therefore, it is possible that diet-induced obesity is caused, at least in part, by a vicious cycle involving altered hippocampal function (113). We speculate that ingestion of high-energy diets and numerous other stressors impair hippocampal-dependent memory, which, in turn, decreases the ppIMI and increases meal frequency and meal size, thereby causing and/or perpetuating diet-induced obesity and possibly exacerbating hippocampal damage (see Fig. 6). Evidence suggests that the cognitive deficits induced by high-energy diets precede the development of obesity. For instance, feeding rats a high-energy diet for relatively short periods (72 h–5 days) impairs hippocampal-dependent spatial and place memory prior to significantly affecting weight (15, 112), and high-energy diet-induced deficits in a hippocampal-dependent feature negative discrimination precede and predict the development of obesity (53).

Fig. 6.

Diet-induced obesity may be caused, at least in part, by a vicious cycle involving altered hippocampal function. Ingestion of high-energy diets and numerous other stressors impair hippocampal-dependent memory, which in turn, decreases the ppIMI and increases meal frequency and meal size, thereby causing and/or perpetuating obesity and possibly exacerbating hippocampal damage.

What Are Key Questions and Future Challenges?

The evidence reviewed above provides converging evidence in support of the hypothesis that hippocampal-dependent episodic memory temporarily inhibits meal onset during the ppIMI. At this juncture, there are several key questions that need to be addressed. For instance, it will be important to ascertain which mnemonic processes influence the duration of the ppIMI. Is it working memory, long-term memory, and/or inhibition of the memory of the rewarding postingestive consequences of eating (58)? Also, if one assumes that the inhibitory actions of hippocampal neurons on meal onset during the ppIMI are temporary, then what factors cause the inhibition to cease? How are distinct memories of different meals generated, particularly for those that involve the same foods and occur in similar contexts and times? This may be addressed, at least in part, by identifying the signals associated with energy intake that contribute to the formation of a meal memory. Is orosensory stimulation sufficient or are postingestive signals required? Also, do hormones and adipokines that stimulate and inhibit intake influence the memory of a meal act at hippocampal neurons to influence the duration of the ppIMI?

A key challenge will be to reconcile the roles of dorsal and ventral hippocampal neurons in meal onset. It also will be important to identify which hippocampal subfields influence meal onset. For instance, if hippocampal neurons regulate meal onset by tracking the time that has elapsed since the last meal, then area CA1 should be critical. The findings reviewed here also point to the need for a neural systems approach that identifies the brain areas involved in meal onset and delineates how their actions are coordinated and integrated. It is likely that many brain regions influence meal timing, including hippocampus (memory and timing), SCN (biological rhythms), basolateral amygdala, and medial prefrontal cortex (cue-potentiated feeding), and lateral hypothalamus. Moreover, other hypothalamic areas and other brain regions may be implicated, such as nucleus accumbens and lateral septum.

Perspectives and Significance

The evidence reviewed above suggests that hippocampal neurons may use interval timing to form an episodic memory of when an event, such as a meal, occurred. These neurons, in turn, likely influence meal onset by temporarily inhibiting regions involved in ingestive behavior. As a result, hippocampal dysfunction increases meal frequency, total energy intake, and weight gain. Given that a host of life events can impair hippocampal function, including excess intake of sugars and fats, it is possible that diet-induced obesity is caused, at least in part, by impaired hippocampal inhibition of meal onset.

GRANTS

The authors are supported by a research grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB 1121886 to M. B. Parent), a Georgia State University Brains and Behavior Program Fellowship (to Y. O. Henderson), a Georgia State University Dissertation Grant (to Y. O. Henderson), and Chi Omega Alumni Educational Grant (to Y. O. Henderson).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta GB. A possible interaction between CCKergic and GABAergic systems in the rat brain. Comp Biochem Physiol Toxicol Pharmacol 128: 11–17, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF, Salah HA, Abu Rashid BE. The combined effect of sleep deprivation and Western diet on spatial learning and memory: role of BDNF and oxidative stress. J Mol Neurosci 50: 124–133, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF, Salah HA, Hasan Z. Vitamin E prevents high-fat high-carbohydrates diet-induced memory impairment: the role of oxidative stress. Physiol Behav 119: 72–78, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral DG, Insausti R, Cowan WM. The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: I. Cytoarchitectonic organization. J Comp Neurol 264: 326–355, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antin J, Gibbs J, Holt J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin elicits the complete behavioral sequence of satiety in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol 89: 784–790, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoki Y, Inokuchi R, Suwa H. Reduced N-acetylaspartate in the hippocampus in patients with fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 213: 242–248, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arikan R, Blake NM, Erinjeri JP, Woolsey TA, Giraud L, Highstein SM. A method to measure the effective spread of focally injected muscimol into the central nervous system with electrophysiology and light microscopy. J Neurosci Methods 118: 51–57, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babri S, Amani M, Mohaddes G, Mirzaei F, Mahmoudi F. Effects of intrahippocampal injection of ghrelin on spatial memory in PTZ-induced seizures in male rats. Neuropeptides 47: 355–360, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babri S, Badie HG, Khamenei S, Seyedlar MO. Intrahippocampal insulin improves memory in a passive-avoidance task in male Wistar rats. Brain Cogn 64: 86–91, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banks WA, Farr SA, Morley JE. The effects of high fat diets on the blood-brain barrier transport of leptin: failure or adaptation? Physiol Behav 88: 244–248, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bannerman DM, Rawlins JN, McHugh SB, Deacon RM, Yee BK, Bast T, Zhang WN, Pothuizen HH, Feldon J. Regional dissociations within the hippocampus—memory and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28: 273–283, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbosa FF, Pontes IM, Ribeiro S, Ribeiro AM, Silva RH. Differential roles of the dorsal hippocampal regions in the acquisition of spatial and temporal aspects of episodic-like memory. Behav Brain Res 232: 269–277, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battey J, Wada E. Two distinct receptor subtypes for mammalian bombesin-like peptides. Trends Neurosci 14: 524–528, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begg DP, Woods SC. The endocrinology of food intake. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9: 584–597, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beilharz JE, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Short exposure to a diet rich in both fat and sugar or sugar alone impairs place, but not object recognition memory in rats. Brain Behav Immun pii: S0889–1591(13)00575–8, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benoit SC, Davis JF, Davidson TL. Learned and cognitive controls of food intake. Brain Res 1350: 71–76, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthoud HR. Interactions between the “cognitive” and “metabolic” brain in the control of food intake. Physiol Behav 91: 486–498, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billard JM. Serine racemase as a prime target for age-related memory deficits. Eur J Neurosci 37: 1931–1938, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blessing W, Mohammed M, Ootsuka Y. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, the basic rest-activity cycle, meal initiation, and bodily homeostasis in rats. Physiol Behav 121: 61–69, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blevins JE, Baskin DG. Hypothalamic-brainstem circuits controlling eating. Forum Nutr 63: 133–140, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolles RC. Grooming behavior in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 53: 306–310, 1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J Comp Neurol 338: 255–278, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunstrom JM, Burn JF, Sell NR, Collingwood JM, Rogers PJ, Wilkinson LL, Hinton EC, Maynard OM, Ferriday D. Episodic memory and appetite regulation in humans. PLos One 7: e50707, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campfield LA, Brandon P, Smith FJ. On-line continuous measurement of blood glucose and meal pattern in free-feeding rats: the role of glucose in meal initiation. Brain Res Bull 14: 605–616, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campfield LA, Smith FJ. Functional coupling between transient declines in blood glucose and feeding behavior: temporal relationships. Brain Res Bull 17: 427–433, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlini VP, Gaydou RC, Schioth HB, de Barioglio SR. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine) decreases the effects of ghrelin on memory retention and food intake. Regul Pept 140: 65–73, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlini VP, Perez MF, Salde E, Schioth HB, Ramirez OA, de Barioglio SR. Ghrelin induced memory facilitation implicates nitric oxide synthase activation and decrease in the threshold to promote LTP in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Physiol Behav 101: 117–123, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlini VP, Varas MM, Cragnolini AB, Schioth HB, Scimonelli TN, de Barioglio SR. Differential role of the hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal raphe nucleus in regulating feeding, memory, and anxiety-like behavioral responses to ghrelin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313: 635–641, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castonguay TW, Kaiser LL, Stern JS. Meal pattern analysis: artifacts, assumptions and implications. Brain Res Bull 17: 439–443, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castonguay TW, Upton DE, Leung PM, Stern JS. Meal patterns in the genetically obese Zucker rat: a reexamination. Physiol Behav 28: 911–916, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cenquizca LA, Swanson LW. Analysis of direct hippocampal cortical field CA1 axonal projections to diencephalon in the rat. J Comp Neurol 497: 101–114, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapelot D, Pasquet P, Apfelbaum M, Fricker J. Cognitive factors in the dietary response of restrained and unrestrained eaters to manipulation of the fat content of a dish. Appetite 25: 155–175, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelikani PK, Haver AC, Reidelberger RD. Ghrelin attenuates the inhibitory effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY(3–36) on food intake and gastric emptying in rats. Diabetes 55: 3038–3046, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, Xing T, Wang M, Miao Y, Tang M, Chen J, Li G, Ruan DY. Local infusion of ghrelin enhanced hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spatial memory through activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the dentate gyrus of adult rats. Eur J Neurosci 33: 266–275, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiapponi C, Piras F, Fagioli S, Piras F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Age-related brain trajectories in schizophrenia: A systematic review of structural MRI studies. Psychiatry Res 214: 83–93, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciccocioppo R, Fedeli A, Economidou D, Policani F, Weiss F, Massi M. The bed nucleus is a neuroanatomical substrate for the anorectic effect of corticotropin-releasing factor and for its reversal by nociceptin/orphanin FQ. J Neurosci 23: 9445–9451, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cimadevilla JM, Miranda R, Lopez L, Arias JL. Bilateral and unilateral hippocampal inactivation did not differ in their effect on consolidation processes in the Morris water maze. Int J Neurosci 118: 619–626, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cimadevilla JM, Wesierska M, Fenton AA, Bures J. Inactivating one hippocampus impairs avoidance of a stable room-defined place during dissociation of arena cues from room cues by rotation of the arena. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3531–3536, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clayton NS, Dickinson A. Episodic-like memory during cache recovery by scrub jays. Nature 395: 272–274, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clifton PG, Vickers SP, Somerville EM. Little and often: ingestive behavior patterns following hippocampal lesions in rats. Behav Neurosci 112: 502–511, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen SJ, Munchow AH, Rios LM, Zhang G, Asgeirsdottir HN, Stackman RW., Jr The rodent hippocampus is essential for nonspatial object memory. Curr Biol 23: 1685–1690, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collier G, Johnson DF, Mitchell C. The relation between meal size and the time between meals: effects of cage complexity and food cost. Physiol Behav 67: 339–346, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cornell CE, Rodin J, Weingarten H. Stimulus-induced eating when satiated. Physiol Behav 45: 695–704, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craft S, Newcomer J, Kanne S, Dagogo-Jack S, Cryer P, Sheline Y, Luby J, Dagogo-Jack A, Alderson A. Memory improvement following induced hyperinsulinemia in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 17: 123–130, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Watson SJ. Ventral subicular interaction with the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: evidence for a relay in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Comp Neurol 332: 1–20, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cummings DE. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiol Behav 89: 71–84, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cunningham E, Janson C. Integrating information about location and value of resources by white-faced saki monkeys (Pithecia pithecia). Animal Cognition 10: 293–304, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev 14: 2950–2961, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Danguir J, Nicolaidis S. Dependence of sleep on nutrients' availability. Physiol Behav 22: 735–740, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darling JN, Ross AP, Bartness TJ, Parent MB. Predicting the effects of a high-energy diet on fatty liver and hippocampal-dependent memory in male rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21: 910–917, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson TL, Chan K, Jarrard LE, Kanoski SE, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. Contributions of the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to energy and body weight regulation. Hippocampus 19: 235–252, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson TL, Hargrave SL, Swithers SE, Sample CH, Fu X, Kinzig KP, Zheng W. Inter-relationships among diet, obesity and hippocampal-dependent cognitive function. Neuroscience 253: 110–122, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson TL, Hargrave SL, Swithers SE, Sample CH, Fu X, Kinzig KP, Zheng W. Inter-relationships among diet, obesity and hippocampal-dependent cognitive function. Neuroscience 253C: 110–122, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davidson TL, Jarrard LE. The hippocampus and inhibitory learning: a ‘Gray’ area? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28: 261–271, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davidson TL, Jarrard LE. A role for hippocampus in the utilization of hunger signals. Behav Neural Biol 59: 167–171, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidson TL, Kanoski SE, Chan K, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Jarrard LE. Hippocampal lesions impair retention of discriminative responding based on energy state cues. Behav Neurosci 124: 97–105, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davidson TL, Kanoski SE, Schier LA, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. A potential role for the hippocampus in energy intake and body weight regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 7: 613–616, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davidson TL, Kanoski SE, Walls EK, Jarrard LE. Memory inhibition and energy regulation. Physiol Behav 86: 731–746, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davidson TL, Monnot A, Neal AU, Martin AA, Horton JJ, Zheng W. The effects of a high-energy diet on hippocampal-dependent discrimination performance and blood-brain barrier integrity differ for diet-induced obese and diet-resistant rats. Physiol Behav 107: 26–33, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davidson TL, Sample CH, Swithers SE. An application of Pavlovian principles to the problems of obesity and cognitive decline. Neurobiol Learn Mem 108C: 172–184, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davis JD, Smith GP, Singh B. Type of negative feedback controlling sucrose ingestion depends on sucrose concentration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R383–R389, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Castro JM. Meal pattern correlations: facts and artifacts. Physiol Behav 15: 13–15, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demaria-Pesce VH, Nicolaidis S. Mathematical determination of feeding patterns and its consequence on correlational studies. Physiol Behav 65: 157–170, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deshmukh SS, Bhalla US. Representation of odor habituation and timing in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 23: 1903–1915, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diano S, Farr SA, Benoit SC, McNay EC, da Silva I, Horvath B, Gaskin FS, Nonaka N, Jaeger LB, Banks WA, Morley JE, Pinto S, Sherwin RS, Xu L, Yamada KA, Sleeman MW, Tschop MH, Horvath TL. Ghrelin controls hippocampal spine synapse density and memory performance. Nat Neurosci 9: 381–388, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dickerson BC, Eichenbaum H. The episodic memory system: neurocircuitry and disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 86–104, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. Feeding signals and brain circuitry. Eur J Neurosci 30: 1688–1696, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drazen DL, Vahl TP, D'Alessio DA, Seeley RJ, Woods SC. Effects of a fixed meal pattern on ghrelin secretion: evidence for a learned response independent of nutrient status. Endocrinology 147: 23–30, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duzel E, Penny WD, Burgess N. Brain oscillations and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 20: 143–149, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eichenbaum H. Declarative memory: insights from cognitive neurobiology. Annu Rev Psychol 48: 547–572, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron 44: 109–120, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fanselow MS, Dong HW. Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron 65: 7–19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of leptin on memory processing. Peptides 27: 1420–1425, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farr SA, Yamada KA, Butterfield DA, Abdul HM, Xu L, Miller NE, Banks WA, Morley JE. Obesity and hypertriglyceridemia produce cognitive impairment. Endocrinology 149: 2628–2636, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Faulconbridge LF, Cummings DE, Kaplan JM, Grill HJ. Hyperphagic effects of brainstem ghrelin administration. Diabetes 52: 2260–2265, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feeney MC, Roberts WA, Sherry DF. Black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) anticipate future outcomes of foraging choices. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 37: 30–40, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fekete EM, Inoue K, Zhao Y, Rivier JE, Vale WW, Szucs A, Koob GF, Zorrilla EP. Delayed satiety-like actions and altered feeding microstructure by a selective type 2 corticotropin-releasing factor agonist in rats: intra-hypothalamic urocortin 3 administration reduces food intake by prolonging the post-meal interval. Neuropsychopharmacology 32: 1052–1068, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Femenia T, Gomez-Galan M, Lindskog M, Magara S. Dysfunctional hippocampal activity affects emotion and cognition in mood disorders. Brain Res 1476: 58–70, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fitzsimons TJ, Le Magnen J. Eating as a regulatory control of drinking in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 67: 273–283, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Floresco SB, Seamans JK, Phillips AG. Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. J Neurosci 17: 1880–1890, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Francis HM, Stevenson RJ. Higher reported saturated fat and refined sugar intake is associated with reduced hippocampal-dependent memory and sensitivity to interoceptive signals. Behav Neurosci 125: 943–955, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garza JC, Guo M, Zhang W, Lu XY. Leptin increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem 283: 18238–18247, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gisou M, Soheila R, Nasser N. Evaluation of the effect of intrahippocampal injection of leptin on spatial memory. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 3: 443–448, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Glendinning JI, Smith JC. Consistency of meal patterns in laboratory rats. Physiol Behav 56: 7–16, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Greenwood CE, Winocur G. Learning and memory impairment in rats fed a high saturated fat diet. Behav Neural Biol 53: 74–87, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Groenewegen HJ, Vermeulen-Van der Zee E, te Kortschot A, Witter MP. Organization of the projections from the subiculum to the ventral striatum in the rat. A study using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Neuroscience 23: 103–120, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hampson RE, Simeral JD, Deadwyler SA. Distribution of spatial and nonspatial information in dorsal hippocampus. Nature 402: 610–614, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hampton RR, Hampstead BM, Murray EA. Selective hippocampal damage in rhesus monkeys impairs spatial memory in an open-field test. Hippocampus 14: 808–818, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Front Human Neurosci 6: 52, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hebben N, Corkin S, Eichenbaum H, Shedlack K. Diminished ability to interpret and report internal states after bilateral medial temporal resection: case H.M. Behav Neurosci 99: 1031–1039, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Henderson YO, Smith GP, Parent MB. Hippocampal neurons inhibit meal onset. Hippocampus 23: 100–107, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Higgs S. Cognitive influences on food intake: the effects of manipulating memory for recent eating. Physiol Behav 94: 734–739, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Higgs S. Memory for recent eating and its influence on subsequent food intake. Appetite 39: 159–166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Higgs S, Williamson AC, Rotshtein P, Humphreys GW. Sensory-specific satiety is intact in amnesics who eat multiple meals. Psychol Sci 19: 623–628, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Higgs S, Woodward M. Television watching during lunch increases afternoon snack intake of young women. Appetite 52: 39–43, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hock BJ, Jr, Bunsey MD. Differential effects of dorsal and ventral hippocampal lesions. J Neurosci 18: 7027–7032, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hoge J, Kesner RP. Role of CA3 and CA1 subregions of the dorsal hippocampus on temporal processing of objects. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88: 225–231, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Holahan MR, Routtenberg A. Lidocaine injections targeting CA3 hippocampus impair long-term spatial memory and prevent learning-induced mossy fiber remodeling. Hippocampus 21: 532–540, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Holland PC, Hatfield T, Gallagher M. Rats with basolateral amygdala lesions show normal increases in conditioned stimulus processing but reduced conditioned potentiation of eating. Behav Neurosci 115: 945–950, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Holland PC, Petrovich GD, Gallagher M. The effects of amygdala lesions on conditioned stimulus-potentiated eating in rats. Physiol Behav 76: 117–129, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hollingsworth EB. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in rat brain membranes: specific binding and stimulation of phosphoinositide breakdown. Mol Pharmacol 35: 689–694, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hughes KC, Shin LM. Functional neuroimaging studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Expert Rev Neurother 11: 275–285, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Dissociations across the dorsal-ventral axis of CA3 and CA1 for encoding and retrieval of contextual and auditory-cued fear. Neurobiol Learn Mem 89: 61–69, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Insausti R, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: II. Cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol 264: 356–395, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Itskov V, Curto C, Pastalkova E, Buzsaki G. Cell assembly sequences arising from spike threshold adaptation keep track of time in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 31: 2828–2834, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jenkins LJ, Ranganath C. Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe activity at encoding predicts temporal context memory. J Neurosci 30: 15558–15565, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jennings CA, Harrison DC, Maycox PR, Crook B, Smart D, Hervieu GJ. The distribution of the orphan bombesin receptor subtype-3 in the rat CNS. Neuroscience 120: 309–324, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson AW. Eating beyond metabolic need: how environmental cues influence feeding behavior. Trends Neurosci 36: 101–109, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jozet-Alves C, Bertin M, Clayton NS. Evidence of episodic-like memory in cuttlefish. Curr Biol 23: R1033–R1035, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kalsbeek A, Strubbe JH. Circadian control of insulin secretion is independent of the temporal distribution of feeding. Physiol Behav 63: 553–558, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kamichi S, Wada E, Aoki S, Sekiguchi M, Kimura I, Wada K. Immunohistochemical localization of gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in the mouse brain. Brain Res 1032: 162–170, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kanoski SE, Davidson TL. Different patterns of memory impairments accompany short- and longer-term maintenance on a high-energy diet. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 36: 313–319, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kanoski SE, Davidson TL. Western diet consumption and cognitive impairment: links to hippocampal dysfunction and obesity. Physiol Behav 103: 59–68, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kanoski SE, Fortin SM, Ricks KM, Grill HJ. Ghrelin signaling in the ventral hippocampus stimulates learned and motivational aspects of feeding via PI3K-Akt signaling. Biol Psychol 73: 915–923, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kanoski SE, Hayes MR, Greenwald HS, Fortin SM, Gianessi CA, Gilbert JR, Grill HJ. Hippocampal leptin signaling reduces food intake and modulates food-related memory processing. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1859–1870, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kanoski SE, Meisel RL, Mullins AJ, Davidson TL. The effects of energy-rich diets on discrimination reversal learning and on BDNF in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of the rat. Behav Brain Res 182: 57–66, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kennedy PJ, Shapiro ML. Motivational states activate distinct hippocampal representations to guide goal-directed behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10805–10810, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kersten A, Strubbe JH, Spiteri NJ. Meal patterning of rats with changes in day length and food availability. Physiol Behav 25: 953–958, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kesner RP, Hunsaker MR. The temporal attributes of episodic memory. Behav Brain Res 215: 299–309, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kesner RP, Hunsaker MR, Warthen MW. The CA3 subregion of the hippocampus is critical for episodic memory processing by means of relational encoding in rats. Behav Neurosci 122: 1217–1225, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.King MV, Kurian N, Qin S, Papadopoulou N, Westerink BH, Cremers TI, Epping-Jordan MP, Le Poul E, Ray DE, Fone KC, Kendall DA, Marsden CA, Sharp TV. Lentiviral delivery of a vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1)-targeting short hairpin RNA vector into the mouse hippocampus impairs cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 464–476, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.King TR, Nance DM. Neuroestrogenic control of feeding behavior and body weight in rats with kainic acid lesions of the lateral septal area. Physiol Behav 37: 475–481, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kirkham TC, Cooper SJ. Naloxone attenuation of sham feeding is modified by manipulation of sucrose concentration. Physiol Behav 44: 491–494, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kishi T, Tsumori T, Ono K, Yokota S, Ishino H, Yasui Y. Topographical organization of projections from the subiculum to the hypothalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 419: 205–222, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Koh MT, Wheeler DS, Gallagher M. Hippocampal lesions interfere with long-trace taste aversion conditioning. Physiol Behav 98: 103–107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kontos A, de Menezes RC, Ootsuka Y, Blessing W. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis precedes food intake in genetically obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats. Physiol Behav 118: 129–137, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kraly FS, Carty WJ, Smith GP. Effect of pregastric food stimuli on meal size and internal intermeal in the rat. Physiol Behav 20: 779–784, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kraus BJ, Robinson RJ, 2nd, White JA, Eichenbaum H, Hasselmo ME. Hippocampal “time cells”: time versus path integration. Neuron 78: 1090–1101, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Krieger DT, Hauser H, Krey LC. Suprachiasmatic nuclear lesions do not abolish food-shifted circadian adrenal and temperature rhythmicity. Science 197: 398–399, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kubik S, Miyashita T, Guzowski JF. Using immediate-early genes to map hippocampal subregional functions. Learn Mem 14: 758–770, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kulkosky PJ, Gibbs J, Smith GP. Feeding suppression and grooming repeatedly elicited by intraventricular bombesin. Brain Res 242: 194–196, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kushner LR, Mook DG. Behavioral correlates of oral and postingestive satiety in the rat. Physiol Behav 33: 713–718, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Languren G, Montiel T, Julio-Amilpas A, Massieu L. Neuronal damage and cognitive impairment associated with hypoglycemia: An integrated view. Neurochem Int 63: 331–343, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lathe R. Hormones and the hippocampus. J Endocrinol 169: 205–231, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Le Magnen J, Devos M. Parameters of the meal pattern in rats: their assessment and physiological significance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 4 Suppl 1: 1–11, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Le Magnen J, Tallon S. [Recording and preliminary analysis of “spontaneous nutritional periodicity” in the white rat]. J Physiol (Paris) 55: 286–287, 1963 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Li JS, Chao YS. Electrolytic lesions of dorsal CA3 impair episodic-like memory in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 89: 192–198, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lima FF, Sita LV, Oliveira AR, Costa HC, da Silva JM, Mortara RA, Haemmerle CA, Xavier GF, Canteras NS, Bittencourt JC. Hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone projections to the septo-hippocampal complex in the rat. J Chem Neuroanat 47: 1–14, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lindqvist A, Mohapel P, Bouter B, Frielingsdorf H, Pizzo D, Brundin P, Erlanson-Albertsson C. High-fat diet impairs hippocampal neurogenesis in male rats. Eur J Neurol 13: 1385–1388, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lorenzini CA, Baldi E, Bucherelli C, Sacchetti B, Tassoni G. Role of dorsal hippocampus in acquisition, consolidation and retrieval of rat's passive avoidance response: a tetrodotoxin functional inactivation study. Brain Res 730: 32–39, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Louis-Sylvestre J, Le Magnen J. Fall in blood glucose level precedes meal onset in free-feeding rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 4 Suppl 1: 13–15, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.MacDonald CJ, Lepage KQ, Eden UT, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal “time cells” bridge the gap in memory for discontiguous events. Neuron 71: 737–749, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Maldonado-Irizarry CS, Swanson CJ, Kelley AE. Glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell control feeding behavior via the lateral hypothalamus. J Neurosci 15: 6779–6788, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mandyam CD. The interplay between the hippocampus and amygdala in regulating aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis during protracted abstinence from alcohol dependence. Front Psychiatry 4: 61, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Manns JR, Howard MW, Eichenbaum H. Gradual changes in hippocampal activity support remembering the order of events. Neuron 56: 530–540, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Maren S, Holt WG. Hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: muscimol infusions into the ventral, but not dorsal, hippocampus impair the acquisition of conditional freezing to an auditory conditional stimulus. Behav Neurosci 118: 97–110, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Martin JH. Autoradiographic estimation of the extent of reversible inactivation produced by microinjection of lidocaine and muscimol in the rat. Neurosci Lett 127: 160–164, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.McEwen BS. The ever-changing brain: cellular and molecular mechanisms for the effects of stressful experiences. Dev Neurobiol 72: 878–890, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.McNay EC, Ong CT, McCrimmon RJ, Cresswell J, Bogan JS, Sherwin RS. Hippocampal memory processes are modulated by insulin and high-fat-induced insulin resistance. Neurobiol Learn Mem 93: 546–553, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Meck WH, Church RM, Matell MS. Hippocampus, time, and memory-A retrospective analysis. Behav Neurosci 127: 642–654, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Mercer JG, Hoggard N, Williams LM, Lawrence CB, Hannah LT, Trayhurn P. Localization of leptin receptor mRNA and the long form splice variant (Ob-Rb) in mouse hypothalamus and adjacent brain regions by in situ hybridization. FEBS Lett 387: 113–116, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mielke JG, Taghibiglou C, Liu L, Zhang Y, Jia Z, Adeli K, Wang YT. A biochemical and functional characterization of diet-induced brain insulin resistance. J Neurochem 93: 1568–1578, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mittal D, Stevenson RJ, Oaten MJ, Miller LA. Snacking while watching TV impairs food recall and promotes food intake on a later TV free test meal. Appl Cognitive Psychol 25: 871–877, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 154.Moon M, Kim S, Hwang L, Park S. Ghrelin regulates hippocampal neurogenesis in adult mice. Endocr J 56: 525–531, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Moosavi M, Naghdi N, Maghsoudi N, Zahedi Asl S, Zahedi Asl S. The effect of intrahippocampal insulin microinjection on spatial learning and memory. Horm Behav 50: 748–752, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Morris RG. Episodic-like memory in animals: psychological criteria, neural mechanisms and the value of episodic-like tasks to investigate animal models of neurodegenerative disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356: 1453–1465, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Moser MB, Moser EI. Functional differentiation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 8: 608–619, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Nagai K, Nishio T, Nakagawa H, Nakamura S, Fukuda Y. Effect of bilateral lesions of the suprachiasmatic nuclei on the circadian rhythm of food-intake. Brain Res 142: 384–389, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Naya Y, Suzuki WA. Integrating what and when across the primate medial temporal lobe. Science 333: 773–776, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Nicolaidis S, Even P. Metabolic rate and feeding behavior. Annals NY Acad Sci 575: 86–104; discussion 104–105, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Nishio T, Shiosaka S, Nakagawa H, Sakumoto T, Satoh K. Circadian feeding rhythm after hypothalamic knife-cut isolating suprachiasmatic nucleus. Physiol Behav 23: 763–769, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief 82: 1–8, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Oliveira AM, Hawk JD, Abel T, Havekes R. Post-training reversible inactivation of the hippocampus enhances novel object recognition memory. Learn Mem 17: 155–160, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Oliveira LA, Gentil CG, Covian MR. Role of the septal area in feeding behavior elicited by electrical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus of the rat. Braz J Med Biol Res 23: 49–58, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Olton DS, Papas BC. Spatial memory and hippocampal function. Neuropsychologia 17: 669–682, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Oomura Y, Hori N, Shiraishi T, Fukunaga K, Takeda H, Tsuji M, Matsumiya T, Ishibashi M, Aou S, Li XL, Kohno D, Uramura K, Sougawa H, Yada T, Wayner MJ, Sasaki K. Leptin facilitates learning and memory performance and enhances hippocampal CA1 long-term potentiation and CaMK II phosphorylation in rats. Peptides 27: 2738–2749, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Osborne B, Dodek AB. Disrupted patterns of consummatory behavior in rats with fornix transections. Behav Neural Biol 45: 212–222, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Pallebage-Gamarallage M, Lam V, Takechi R, Galloway S, Clark K, Mamo J. Restoration of dietary-fat induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction by anti-inflammatory lipid-modulating agents. Lipids Health Dis 11: 117, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Parent MB, Ogawa Y, Victoria N, Murphy AZ. Impact of neonatal pain and inflammation on hippocampal-dependent memory in middle-aged rats In: Proceedings of the Society for Neuroscience, 2011 Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 170.Park HR, Park M, Choi J, Park KY, Chung HY, Lee J. A high-fat diet impairs neurogenesis: involvement of lipid peroxidation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neurosci Lett 482: 235–239, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Parsons TC, Otto T. Time-limited involvement of dorsal hippocampus in unimodal discriminative contextual conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 94: 481–487, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Pathan AR, Gaikwad AB, Viswanad B, Ramarao P. Rosiglitazone attenuates the cognitive deficits induced by high fat diet feeding in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 589: 176–179, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Penzes P, Buonanno A, Passafaro M, Sala C, Sweet RA. Developmental vulnerability of synapses and circuits associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neurochem 126: 165–182, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Petrovich GD. Forebrain networks and the control of feeding by environmental learned cues. Physiol Behav 121: 10–18, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Petrovich GD, Hobin MP, Reppucci CJ. Selective Fos induction in hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin, but not melanin-concentrating hormone neurons, by a learned food-cue that stimulates feeding in sated rats. Neuroscience 224: 70–80, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Petrovich GD, Holland PC, Gallagher M. Amygdalar and prefrontal pathways to the lateral hypothalamus are activated by a learned cue that stimulates eating. J Neurosci 25: 8295–8302, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Petrovich GD, Ross CA, Holland PC, Gallagher M. Medial prefrontal cortex is necessary for an appetitive contextual conditioned stimulus to promote eating in sated rats. J Neurosci 27: 6436–6441, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]