Abstract

Early detection of early gastric cancer (EGC) is important to improve the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Recent advances in endoscopic modalities and treatment devices, such as image-enhanced endoscopy and high-frequency generators, may make endoscopic treatment, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection, a therapeutic option for gastric intraepithelial neoplasia. Consequently, short-term outcomes of endoscopic resection (ER) for EGC have improved. Therefore, surveillance with endoscopy after ER for EGC is becoming more important, but how to perform endoscopic surveillance after ER has not been established, even though the follow-up strategy for more advanced gastric cancer has been outlined. Therefore, a surveillance strategy for patients with EGC after ER is needed.

Keywords: Early gastric cancer, Endoscopic resection, Synchronous gastric cancer, Metachronous gastric cancer, Surveillance

Core tip: Recent advances in endoscopic modalities and treatment devices may make endoscopic treatment, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection, a therapeutic option for early gastric cancer (EGC). Consequently, short-term outcomes of endoscopic resection (ER) for EGC have improved. Therefore, surveillance with endoscopy after ER for EGC is becoming more important, but how to perform endoscopic surveillance after ER has not been established, even though the follow-up strategy for more advanced gastric cancer has been outlined. In this review, we discuss clinical problems in surveillance after ER for EGC.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the second most common cause of death from cancer worldwide[1,2], and more than half of the world’s gastric cancer cases arise in Eastern Asia. Early gastric cancer (EGC) is typically small and asymptomatic and has a good prognosis[3,4], but advanced gastric cancer has a higher mortality rate[5]. Therefore, early detection and treatment could contribute to improved prognoses for patients with gastric cancer. Screening with endoscopy and biopsy sampling is important for patients with premalignant lesions and may lead to early cancer detection[6,7]. In Japan, a mass-screening program for gastric cancer is conducted on a nationwide scale because of the high prevalence of gastric cancer. Such a screening program may help to detect EGC that is treated by endoscopic resection (ER).

Japanese guidelines classify EGC into the following three groups, as proposed by Gotoda et al[8], when considering the indication of ER for EGC: the “guideline group”, the “expanded guideline group” and the “non-curative group”. Based on the tumor characteristics, the guideline group is defined as mucosal differentiated cancer with the largest diameter measuring < 20 mm. In Japan, ER is definitely indicated for this group. If the lesion meets Japanese guideline criteria and R0 resection is achieved, it is classified as a curative tumor, which does not require need further intense follow-up because it has a negligible risk for lymph node or distant metastasis[9-11]. Moreover, with the advancement of endoscopy and high-frequency generators, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been developed. Consequently, the short-term outcomes of ER for EGC have improved[12,13].

However, patients who have undergone ER for EGC are considered at high risk for having other gastric cancer lesions. The incidence of local recurrence is decreasing because of ESD, which enables the evaluation of the horizontal and vertical margins of the resected specimen. Therefore, the risk of secondary gastric neoplasms developing during the follow-up period after ER has become a serious problem. In this review, we discuss clinical problems in developing a secondary gastric cancer after ER in patients with EGC, except for patients with non-curative resection based on Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[14], with the goal of targeting synchronous and metachronous multiple gastric cancer development after ER.

GASTRIC CANCER RISK IN PATIENTS WITH HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

Stomach carcinogenesis is generally considered to originate from chronic active inflammation of the stomach mucosa caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, followed in an ideal model by atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia or adenoma, some of which eventually develop into gastric adenocarcinomas[15]. The incidence range of gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia is 0.1%-0.5%[7,16]. In particular, elderly persons often have multiple gastric cancers because individuals older than 65 have advanced degrees of intestinal metaplasia, a high risk for developing gastric cancer[17]. Yoshida et al[18] indicated that a high serum pepsinogen level and a high H. pylori antibody titer were risk factors for developing cancer in H. pylori-infected subjects from a large cohort of 4655 healthy subjects. The risk of developing gastric cancer cannot be abolished even if H. pylori is successfully eradicated[19]. However, the prevalence of gastric cancer in subjects who have not been infected with H. pylori is very low. Matsuo et al[20] calculated a gastric cancer prevalence of 0.66% (95%CI: 0.41-1.01) in the Japanese population without H. pylori.

DEFINITIONS OF SYNCHRONOUS AND METACHRONOUS MULTIPLE GASTRIC CANCER DEVELOPMENT

Even patients after curative ER for EGC have higher risks of multiple cancer development than patients with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia without past EGC. The doubling time of EGC is relatively long, ranging from 1.6 to 9.5 years[21]. Therefore, some occult lesions in the stomach might be observed when detecting a first EGC. Moreover, detecting secondary cancer after initial ER depends on how often the surveillance endoscopy is performed, which can include a lead-time bias. It is difficult to determine whether a secondary cancer is synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer. Until now, there have not been strict definitions of these lesions after ER.

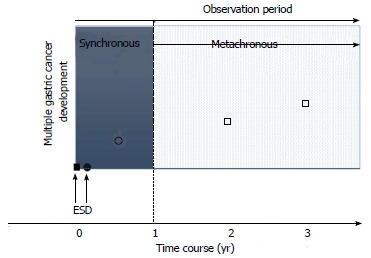

In this review, we define multiple gastric cancer development as synchronous (within 1 year) or metachronous cancer according to the time at which the multiple cancers develop. Moreover, synchronous cancer is classified as “concomitant cancer” or “missed cancer”. Concomitant cancer is defined as multiple cancers that had already been detected and diagnosed before the initial ESD. In recent reports, there is a consensus that cancers detected within 1 year after the initial ER should be regarded as ‘missed’ synchronous cancers[22,23]. We define missed cancer as cancer that is detected within 1 year, except for concomitant cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Definition of multiple gastric cancer development. Synchronous (within 1 year) or metachronous cancer (□) according to the time at which the multiple cancers developed. Synchronous cancer is also classified as “concomitant cancer” (●) or “missed cancer” (○). ■: Primary gastric cancer.

CONCOMITANT AND MISSED SYNCHRONOUS GASTRIC CANCER AFTER ER

There are many reports about synchronous gastric cancer in surgically resected stomachs, with an incidence ranging from 4.8% to 14.6%[24-27] (Table 1). In addition, the incidence of synchronous multiple gastric cancers among the patients treated by ER ranges from 1.2% to 19.2%[10,19,28,29] (Table 2). In our large cohort, synchronous cancer was detected in 110 patients within 1 year after ESD [8.7% (110/1258 patients)]. Twenty-one out of 110 patients (19%) were considered to have missed cancers because these lesions were not detected at the preoperative endoscopic evaluation before initial ESD. The overall rate of missed cancer was 1.7% (21/1258)[19]. In surgically resected cases, missed synchronous cancer cases range from 23% to 64% of gastric cancers (Table 1). Compared with surgical cases, our missed rate was lower because it makes a difference whether a gastric cancer is in the early or advanced stage. Therefore, we should keep in mind that the missed rate was not negligible and that we need an endoscopic surveillance strategy that addresses the problem of missed cancer.

Table 1.

Incidence of synchronous gastric cancers in the surgically resected stomach

| Ref. | Overall | Missed lesion | ||

| Noguchi et al[42], 1985 | 6.50% | 468/7220 | ||

| Ezaki et al[24], 1987 | 14.60% | 75/512 | ||

| Honmyo et al[43], 1989 | 4.80% | 40/839 | 53% | 21/40 |

| Mitsudomi et al[44], 1989 | 8.30% | 83/997 | 23% | 42/182 |

| Kosaka et al[25], 1990 | 5.80% | 49/852 | ||

| Kodera et al[26], 1995 | 5.70% | 160/2790 | 53% | 85/160 |

| Kodama et al[45], 1996 | 6.80% | 107/1458 | 64% | 69/107 |

| Fujita et al[46], 2009 | 8.70% | 266/3042 | ||

| Lee et al[27], 2010 | 5.20% | 51/986 | 28% | 14/51 |

| Total | 6.90% | 1299/18696 | 39% | 210/540 |

Table 2.

Incidence of synchronous gastric cancers in the endoscopically resected stomach within 1 yr of the initial endoscopic resection

| Ref. | Overall | Missed lesion | |

| Arima et al[23], 1999 | 6.60% | 5/76 | NA |

| Nasu et al[10], 2005 | 11% | 16/143 | NA |

| Nakajima et al[9], 2006 | 9.20% | 581/633 | NA |

| Kobayashi et al[28], 2010 | 19.20% | 45/234 | NA |

| Han et al[29], 2011 | 4% | 7/176 | NA |

| Kato et al[19], 2013 | 8.70% | 110/1258 | 19% (21/110) |

| Kim et al[47], 2013 | 2% | 122/602 | NA |

| Total | 8.10% | 253/3122 | |

Including 14 adenomas;

Including 5 adenomas. NA: Not available.

Four of 21 missed lesions (19%) were massively invading cancers (including one advanced cancer) in our study[19], which suggests that we should perform preoperative screening carefully and should consider missed cancer as a problem because we tend to focus on the initial lesion. To predict missed cancers, we found that the endoscopist’s experience was an independent predictor of missed cancer. However, Lee et al[27] reported that expert endoscopists can miss other lesions in as many as 27.5% of patients and that smaller size was correlated with missed lesions. It might be difficult to decrease the number of missed lesions in the near future despite recent endoscopic advances, such as image-enhanced endoscopy and magnifying endoscopy. Therefore, we should pay special attention to the possibility of missed cancers, not only initially detected lesions at the first evaluation, and the first surveillance EGD should be performed soon after the ESD so as not to miss cancers.

METACHRONOUS GASTRIC CANCER AFTER ER

In reports conducted on patients with surgically resected stomachs in the remnant stomach after surgery for gastric cancer, the rate of metachronous gastric cancer ranges from 1.8% to 5%[30-32]. Therefore, the remnant stomach is at high risk for developing metachronous gastric cancer. ER contributes to preserving the stomach compared with surgically resected stomach and maximizing quality of life. Therefore, patients with EGC resected by ER are considered at higher risk for developing metachronous gastric cancer than surgically resected patients because the former have more remnant stomach and tend to survive longer. The metachronous cancer rate after ER ranges from 2.7% to 14% (Table 3). Nakajima et al[9] reported that metachronous gastric cancer had an overall incidence of 8.2% (52 out of 633 patients) and that the annual incidence was constant (cumulative 3-year incidence 5.9%). The average time to detect a first metachronous gastric tumor after the initial ER was 3.1 ± 1.7 years (range, 1-8.6 years)[9]. We also found that the cumulative incidence curve revealed a linear increase. The cumulative incidence rates of metachronous cancers at 2, 3, 4 and 5 years were 3.7%, 6.9%, 10% and 16%, respectively. Based on these data, the metachronous gastric cancer incidence curve, except for synchronous cancer, seems to increase linearly by 3%-3.5%[9,19,33].

Table 3.

Metachronous cancer rate after endoscopic resection

| Ref. | Rate | Follow up period (yr) | |

| Arima et al[23], 1999 | 7.90% | 6/76 | 71 |

| Nasu et al[10], 2005 | 14% | 20/143 | 4.8 (median) |

| Nakajima et al[9], 2006 | 8.40% | 53/633 | 4.4 (mean) |

| Kim et al[48], 2007 | 2.70% | 13/479 | 3.3 (median) |

| Kobayashi et al[28], 2010 | 12.80% | 30/234 | 5 (median) |

| Lee et al[49], 2011 | 3.30% | 15/458 | 2.2 (median) |

| Kato et al[19], 2013 | 5.20% | 65/1258 | 2.2 (mean) |

| Total | 6.70% | 202/3281 |

All patients were followed up for 7 yr.

LOCAL RECURRENCE AFTER ER

Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) techniques are associated with the risk of local recurrence because it is difficult to achieve en bloc resection, in particular with larger lesions. Until recently, EMR was widely accepted as a useful, standard treatment for gastrointestinal tract neoplasms, but EMR has been replaced by ESD because en bloc resection of specimens larger than 20 mm is difficult to perform with EMR. Local recurrence strongly depends on whether the initial lesion is completely resected. With piecemeal resection or marginal-positive resection (not curative), local recurrence ranges from 4.4% to 18% (Table 4). Using ESD, en bloc marginal-negative resection can be performed with larger specimens. Developing local recurrence after complete en bloc resection in mucosal gastric cancers occurs rarely. In fact, our study revealed that local recurrence was seen in only 0.40% of patients (5/1258)[19]. This rate was quite low, but not zero. Park et al[11] also reported complete en bloc resection in one patient who developed local recurrence after complete resection by ESD. It is speculated that it is difficult to detect a very small concomitant lesion or precancerous lesion near the initial ESD site at initial evaluation or that detection depends on the status of the resected specimen reviewed by pathologists or each pathologist’s experience. To evaluate resected specimens properly, the ER specimen should be cut parallel to the closest margin direction. When the negative margin is obvious, the specimens are step-sectioned along the minor axis of the specimen to obtain more information. The Japanese Gastric Cancer Association recommended that a section width of 2 mm allows for a more accurate diagnosis. We should remember that complete resection does not exclude the possibility of local recurrence in cases where R0 resection is achieved.

Table 4.

Local recurrence rate after endoscopic resection

| Ref. |

Local recurrence rate |

|||

|

EMR |

ESD |

|||

| Curative | Not curative | Curative | Not curative | |

| Oka et al[50], 2006 | 2.90% | 4.40% | 0% | 0% |

| Kim et al[48], 20071 | 6.0% (24/399) | 15% (10/68) | ||

| Park et al[11], 2010 | 18% (9/50, not en bloc; 18) | 3.7% (7/189, not en bloc: 25) | ||

| Lee et al[49], 2011 | NA | NA | 0.7% (2/276, not en bloc: 3)2 | |

| NA | NA | 0% (0/182, not en bloc: 22)3 | ||

| Kato et al[19], 2013 | NA | NA | 0.4% (5/1258) | |

| Tanabe et al[51], 20134 | 4.2%(15/359)5 | 0.2% (1/421) | ||

“Not curative” includes piecemeal resection or marginal positive resection.

Including 34 lesions treated by ESD (6.6%);

Guideline group;

Expanded guideline group;

For lesions meeting the JGCA criteria, the local recurrence rates were 2.9% in the EAM group and 0% in the ESD group;

Treated by endoscopic aspiration mucosectomy (EAM). EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; NA: Not available.

INTERVENTION FOR SECONDARY CANCER AFTER ER OF GASTRIC CANCER

In a study by our group, 169 of 175 secondary cancers (97%) after ESD were treated by re-ESD[19]. Among these cancers, 164 lesions were diagnosed as fitting the guideline or expanded guideline group and were followed up without additional treatment. Of the remaining five lesions, two were diagnosed as mucosal undifferentiated adenocarcinomas, and three were diagnosed as submucosal cancers after ESD; these patients then underwent additional gastrectomies. In addition, six lesions were treated by gastrectomy. Of these cases, four were pathologically diagnosed as belonging to the guideline or expanded guideline group after gastrectomy, and the remaining two were pathologically diagnosed as non-curative. Altogether, seven lesions were diagnosed as non-curative: three were intramucosal undifferentiated cancers, and four were massively invading cancers. Nakajima et al[9] concluded that frequent follow-up examinations negatively affect a patient’s quality of life and result in an increase in overall medical expenses. Similarly, we also found that almost all secondary cancers after ESD were treatable by re-ESD[19]. Nakajima et al[9] reported that almost all first metachronous gastric cancers (96.2%) were treated curatively with re-ER. Considering those re-ER rates for metachronous cancer (96.2%, 97%), most metachronous secondary cancers can be non-surgically treated after the follow-up endoscopy.

HANDLING OF GASTRIC HIGH- AND LOW-GRADE INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASMS

Gastric intraepithelial neoplasia, also called dysplasia or adenoma, is considered to be a precancerous lesion with a variable clinical course. The natural course of gastric intraepithelial neoplasia remains unclear. In particular, it is difficult to differentiate dysplasia/adenoma and adenocarcinoma using biopsy specimens because of the inaccuracy of obtaining a biopsy specimen from a malignant region of an adenoma[34,35]. Previous prospective long-term follow-up studies indicated that the gastric cancer-developing incidence in low-grade intraepithelial neoplasms (LGIN) is approximately 10%[35]. This low risk of malignant transformation compared to high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN) may be due to the slowly progressive natural course of LGIN and supports a follow-up strategy. Once developing HGIN is diagnosed from biopsy specimens, 90% of them are ultimately diagnosed as adenocarcinoma after ER[36]. Generally, it is recommended that category 4 lesions (based on the Vienna classification: high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal cancer) be resected because they have a high potential for progression to adenocarcinoma[35]. Our current knowledge based on initial endoscopic intervention - not follow-up - indicates that over 40% of LGINs are diagnosed as adenocarcinoma after ER. Considering the high incidence of adenocarcinoma in HGIN, it could be recommended that ER be considered an indication for HGIN detected as a secondary lesion after ER. We are currently evaluating whether ESD is a valid strategy for gastric intraepithelial neoplasms with regard to safety and cost-effectiveness (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: http://www.umiNAc.jp/ctr/, number UMIN000007476).

H. PYLORI ERADICATION

Extensive epidemiologic studies have shown that H. pylori infection is a major risk factor for developing gastric cancer[37]. According to most retrospective case-control and prospective epidemiologic studies, the risk of developing gastric cancer is two- to six-fold higher in patients with H. pylori infection than in patients without H. pylori infection[38]. Furthermore, some of the trials eradicating H. pylori have shown that successful eradication reduces the frequency of gastric cancer in high-risk populations, but H. pylori eradication may not completely abolish the risk for gastric carcinogenesis[39]. Therefore, H. pylori eradication might reduce secondary cancer after ER. Fukase et al[33] prospectively reported that prophylactic eradication of H. pylori after ER of EGC reduced secondary metachronous cancer by approximately one-third (OR = 0.353). Therefore, it is highly recommended that H. pylori be eradicated after ER for EGC. Based on Fukase’s report, as of 2010, Japanese health insurance is allowed to cover H. pylori eradication therapy after ER for EGC. However, some retrospective cohort studies report no difference in the rate of metachronous cancer between patients who undergo successful H. pylori eradication and those who do not receive eradication treatment[19,40,41]. Therefore, because of the short 3-year observation of Fukase’s report, whether H. pylori eradication reduces metachronous recurrence after ER for EGC is considered controversial. We speculate that the requirement for H. pylori eradication depends on how many high-risk patients have synchronous or metachronous recurrence. Therefore, it is important to conduct annual surveillance endoscopies after ER in patients with or without successful eradication, though patients with successful eradication will require longer surveillance until it is clear how long and how often surveillance endoscopy needs to be performed.

SURVEILLANCE STRATEGY FOR SECONDARY CANCER AFTER ER OF GASTRIC CANCER

There are no randomized trials to guide surveillance strategies after curative EGC resection. The 2013 consensus-based guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) suggest the same follow-up strategy that is used for more advanced disease, regardless of treatment type (NCCN Guideline version 2, 2013, http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp). The guidelines state that even for Tis or T1 with N0 lesions achieving R0, all patients should be followed up systematically, and follow-up should include a complete history and physical examination every 3 to 6 mo for 1 to 2 years, every 6 to 12 mo for 3 to 5 years and annually thereafter, along with other advanced stages. However, it is important to consider the curability of the initial ER. In Japan, ER is definitely indicated for guideline groups according to Japanese guideline criteria[14]. If the lesions meet the Japanese guideline criteria and R0 resection is achieved, the lesion is classified as a curative group and does not require further intense follow-up because it has a negligible risk for lymph node or distant metastasis[9-11].

Therefore, we recommend the following surveillance strategies: (1) an endoscopist who has performed at least 500 esophagogastroduodenoscopies should perform the preoperative screening; (2) intensive (every 6 mo) surveillance is preferred in the first year after ER to detect missed concomitant invasive cancers; and (3) annual surveillance should be performed for at least 5 years after the ER. From the viewpoint of avoiding gastrectomy and preserving most of the stomach and quality of life, it might not be important to strictly define the difference between synchronous and metachronous gastric cancer.

At this time, it is unclear whether the developing metachronous cancer is self-limiting or permanent. In report by Kobayashi et al[28], which included a follow-up longer than 10 years, showed that the metachronous recurrence curve reached a plateau and that the risk was not continuous after 10 years. In the future, the validity of our recommendations should be confirmed with a prospective study, and it is necessary to evaluate whether metachronous cancer is self-limiting.

CONCLUSION

It has not yet been established how endoscopic surveillance after curative ER should be performed. The rate of synchronous multiple gastric cancers among patients treated by ER is < 20%. After 1 year, the metachronous gastric cancer incidence increases linearly at an approximate rate of 3% per year. However, approximately 96% of patients with developing metachronous cancer were treated curatively with re-ER. Considered together with the population of ESD and advances in endoscopy, local recurrence or missed cancer may be negligible. Therefore, it might not be necessary to perform intensive endoscopy surveillance within 1 year to detect local recurrence. Surveillance endoscopies can permit the endoscopic treatment of cancers that may have been missed or that develop later.

In conclusion, skilled endoscopists should perform preoperative screening before initial ESD. We recommend that intensive (every 6 mo) surveillance be performed in the first year after ER to detect missed concomitant invasive cancers, and then annual surveillance should be performed for at least 5 years. In the future, it should be clarified whether longer surveillance is necessary.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Chang JH, Czakó L, Ikematsu H, Vieth M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 8:S4–66. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23:6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uedo N, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ishihara R, Higashino K, Takeuchi Y, Imanaka K, Yamada T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Longterm outcomes after endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:88–92. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everett SM, Axon AT. Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut. 1997;41:142–150. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervantes A, Roselló S, Roda D, Rodríguez-Braun E. The treatment of advanced gastric cancer: current strategies and future perspectives. Ann Oncol. 2008;19 Suppl 5:v103–v107. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, Kim JJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Wu KC, Wu DC, Sollano J, Kachintorn U, et al. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945–952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/pl00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Yokoi C, Saito D. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasu J, Doi T, Endo H, Nishina T, Hirasaki S, Hyodo I. Characteristics of metachronous multiple early gastric cancers after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2005;37:990–993. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JC, Lee SK, Seo JH, Kim YJ, Chung H, Shin SK, Lee YC. Predictive factors for local recurrence after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: long-term clinical outcome in a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2842–2849. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akasaka T, Nishida T, Tsutsui S, Michida T, Yamada T, Ogiyama H, Kitamura S, Ichiba M, Komori M, Nishiyama O, et al. Short-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric neoplasm: multicenter survey by osaka university ESD study group. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Kakushima N, Yamamoto Y, Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara J, Ishii N, et al. A multicenter survey of the management after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection related to postoperative bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:435–439. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1886-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanaoka K, Oka M, Yoshimura N, Mukoubayashi C, Enomoto S, Iguchi M, Magari H, Utsunomiya H, Tamai H, Arii K, et al. Risk of gastric cancer in asymptomatic, middle-aged Japanese subjects based on serum pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody levels. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:917–926. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nitta T, Egashira Y, Akutagawa H, Edagawa G, Kurisu Y, Nomura E, Tanigawa N, Shibayama Y. Study of clinicopathological factors associated with the occurrence of synchronous multiple gastric carcinomas. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10120-008-0493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida T, Kato J, Inoue I, Yoshimura N, Deguchi H, Mukoubayashi C, Oka M, Watanabe M, Enomoto S, Niwa T, et al. Cancer development based on chronic active gastritis and resulting gastric atrophy as assessed by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody titer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1445–1457. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, Yoshio T, Nakamura T, Komori M, Kawai N, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425–1432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuo T, Ito M, Takata S, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer among Japanese. Helicobacter. 2011;16:415–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohli Y, Kawai K, Fujita S. Analytical studies on growth of human gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3:129–133. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uemura N, Okamoto S. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in Japan. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:819–827. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arima N, Adachi K, Katsube T, Amano K, Ishihara S, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. Predictive factors for metachronous recurrence of early gastric cancer after endoscopic treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:44–47. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esaki Y, Hirokawa K, Yamashiro M. Multiple gastric cancers in the aged with special reference to intramucosal cancers. Cancer. 1987;59:560–565. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870201)59:3<560::aid-cncr2820590334>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosaka T, Miwa K, Yonemura Y, Urade M, Ishida T, Takegawa S, Kamata T, Ooyama S, Maeda K, Sugiyama K. A clinicopathologic study on multiple gastric cancers with special reference to distal gastrectomy. Cancer. 1990;65:2602–2605. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900601)65:11<2602::aid-cncr2820651134>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Torii A, Uesaka K, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T, Kito T. Incidence, diagnosis and significance of multiple gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1540–1543. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HL, Eun CS, Lee OY, Han DS, Yoon BC, Choi HS, Hahm JS, Koh DH. When do we miss synchronous gastric neoplasms with endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi M, Narisawa R, Sato Y, Takeuchi M, Aoyagi Y. Self-limiting risk of metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han JS, Jang JS, Choi SR, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, Kim SJ, Sohn YJ, Lee EJ. A study of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1099–1104. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.591427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosokawa O, Kaizaki Y, Watanabe K, Hattori M, Douden K, Hayashi H, Maeda S. Endoscopic surveillance for gastric remnant cancer after early cancer surgery. Endoscopy. 2002;34:469–473. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeda J, Toyonaga A, Koufuji K, Kodama I, Aoyagi K, Yano S, Ohta J, Shirozu K. Early gastric cancer in the remnant stomach. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1907–1911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls JC. Stump cancer following gastric surgery. World J Surg. 1979;3:731–736. doi: 10.1007/BF01654802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato M, Nishida T, Tsutsui S, Komori M, Michida T, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Kitamura S, Zushi S, Nishihara A, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for gastric noninvasive neoplasia: a multicenter study by Osaka University ESD Study Group. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishida T, Tsutsui S, Kato M, Inoue T, Yamamoto S, Hayashi Y, Akasaka T, Yamada T, Shinzaki S, Iijima H, et al. Treatment strategy for gastric non-invasive intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2011;2:93–99. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v2.i6.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung MK, Jeon SW, Park SY, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Bae HI. Endoscopic characteristics of gastric adenomas suggesting carcinomatous transformation. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2705–2711. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2373–2379. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Murata H, Nishida T, Komori M, Yasumaru M, Ishii S, Sasayama Y, Kawano S, Hayashi N. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer: underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1671–1680. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i11.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanaoka K, Oka M, Ohata H, Yoshimura N, Deguchi H, Mukoubayashi C, Enomoto S, Inoue I, Iguchi M, Maekita T, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents cancer development in subjects with mild gastric atrophy identified by serum pepsinogen levels. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2697–2703. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maehata Y, Nakamura S, Fujisawa K, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Asano K, Fuyuno Y, Yamaguchi K, Egashira I, Kim H, et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noguchi Y, Ohta H, Takagi K, Ike H, Takahashi T, Ohashi I, Kuno K, Kajitani T, Kato Y. Synchronous multiple early gastric carcinoma: a study of 178 cases. World J Surg. 1985;9:786–793. doi: 10.1007/BF01655194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honmyo U, Misumi A, Murakami A, Haga Y, Akagi M. Clinicopathological analysis of synchronous multiple gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1989;15:316–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsudomi T, Watanabe A, Matsusaka T, Fujinaga Y, Fuchigami T, Iwashita A. A clinicopathological study of synchronous multiple gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1989;76:237–240. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kodama M, Tur GE, Shiozawa N, Koyama K. Clinicopathological features of multiple primary gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62:57–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199605)62:1<57::AID-JSO12>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujita T, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, Nakagohri T, Konishi M, Kinoshita T. Clinical and histopathological features of remnant gastric cancers, after gastrectomy for synchronous multiple gastric cancers. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:466–471. doi: 10.1002/jso.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HH, Cho EJ, Noh E, Choi SR, Park SJ, Park MI, Moon W. Missed synchronous gastric neoplasm with endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm: experience in our hospital. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JJ, Lee JH, Jung HY, Lee GH, Cho JY, Ryu CB, Chun HJ, Park JJ, Lee WS, Kim HS, et al. EMR for early gastric cancer in Korea: a multicenter retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee H, Yun WK, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, Rhee JC, Kim JJ. A feasibility study on the expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1985–1993. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanabe S, Ishido K, Higuchi K, Sasaki T, Katada C, Azuma M, Naruke A, Kim M, Koizumi W. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a retrospective comparison with conventional endoscopic resection in a single center. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:130–136. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]