Abstract

A 27-year-old woman with a history of bileaflet mitral valve prolapse and moderate mitral regurgitation presented to our emergency with untractable polymorphic wide complex tachycardia and unstable haemodynamics. After cardiopulmonary resuscitation, return of spontaneous circulation was achieved 30 min later. Her post-resuscitation ECG showed a prolonged QT interval which progressively normalised over the same day. Her laboratory investigations revealed hypocalcaemia while other electrolytes were within normal limits. A diagnosis of ventricular arrhythmia secondary to structural heart disease further precipitated by hypocalcaemia was made. Further hospital stay did not reveal a recurrence of prolonged QT interval or other arrhythmias except for an episode of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. However, the patient suffered diffuse hypoxic brain encephalopathy secondary to prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Background

Mitral valve prolapse in a majority of patients is recognised as a benign clinical condition without serious outcomes. However, in a select set of patients in the presence of other precipitating factors, there has been evidence that this abnormality increases the risk of life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In this particular patient, we believe that possible repolarisation abnormalities from mitral valve prolapse and mitral regurgitation with the additive effect of hypocalcaemia resulted in a prolonged QT interval and precipitated torsades de pointes. By highlighting this case presentation, we attempt to emphasise the importance of risk stratification and close monitoring of such patients so that future events can be prevented.

Case presentation

A young 27-year-old apparently healthy woman presented to our emergency unconscious and unresponsive with the following details.

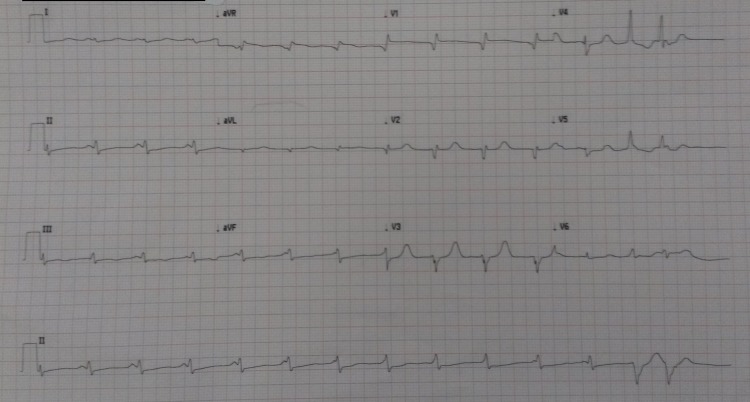

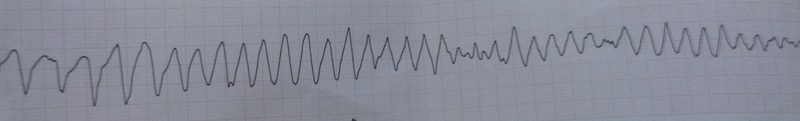

The patient had a history of depression and infertility and was on in vitro fertilisation treatment. On hearing the news of her negative results, she became anxious, developed palpitations, chest pain and shortly thereafter collapsed in front of her family. Chest compressions were initiated immediately by her family till paramedics arrived and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was continued in the ambulance. The first rhythm strip showed torsades de pointes (figure 1) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation continued. Synchronised electrical cardioversion was attempted five times in the ambulance and four times in the hospital. After achieving return of spontaneous circulation the ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (figure 2). Amiodarone and lidocaine infusions were started and the patient reverted to sinus rhythm with a prolonged QT interval (QT duration 458 ms/QTc duration 501 ms—figure 3).

Figure 1.

ECG showing torsades de pointes in the ambulance.

Figure 2.

ECG ventricular tachycardia after return of spontaneous circulation.

Figure 3.

ECG normal sinus rhythm with prolongation of QT interval (QT duration 458 ms/QTc duration 501 ms).

At that time her blood pressure was 120/80 mm Hg and pulse was 100 bpm. Chest was clear and cardiovascular examination did not yield any abnormal heart sounds. The patient required ventilator support and was transferred to the coronary care unit.

History was negative for drug abuse, drug overdose, antihistamine treatment or antibiotic intake.

Her history was suggestive of frequent palpitations during emotional distress since childhood. Additionally she had frequent episodes of fainting attacks for which she did not consult a doctor.

She presented to us in 2007 with a history of palpitations. ECG at that time showed frequent polymorphic premature ventricular contractions. Echocardiography showed anterior and posterior mitral leaflet prolapse with myxomatous changes, moderate mitral regurgitation and normal left ventricular dimensions and function. She was managed with a β-blocker.

She presented to the cardiology clinic in 2011 again with frequent episodes of palpitations and dizziness with slowing of her heart beat. Holter monitoring carried out in 2011 stated multifocal ventricular extrasystoles, transient atrial premature beats and two transient short runs of ventricular tachycardia. Her dose of β-blocker was increased and she was asked to follow-up regularly.

Family history was insignificant for arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death.

Investigations

Her initial blood investigations showed hypocalcaemia (7.7 mg/dL). Magnesium was 2.43 mg/dL and potassium was 3.8 mml/L and similarly other electrolytes were within the normal parameters. Investigations showed haemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL, white cell count 16.9×103 /µL and platelet count 312×103 /µL. All cardiac enzymes were elevated. Creatinine was 0.8 mg/dL. Lipid profile was within normal limit.

ECG showed normalisation of the QT interval during the course of the day. The patient had no further episodes of QT-interval prolongation. Frequent premature ventricular contractions were present. There was a single episode of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia which resolved without treatment.

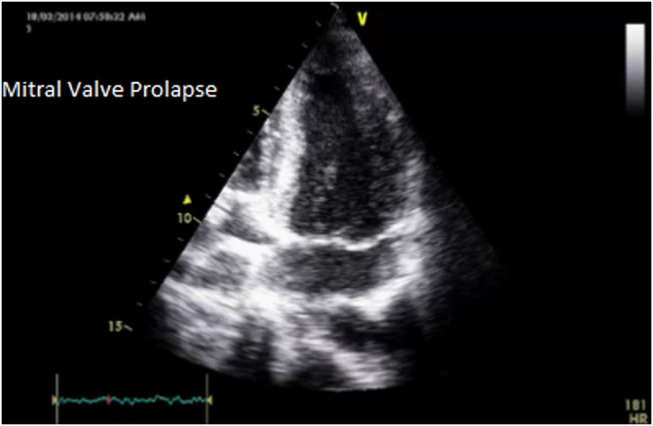

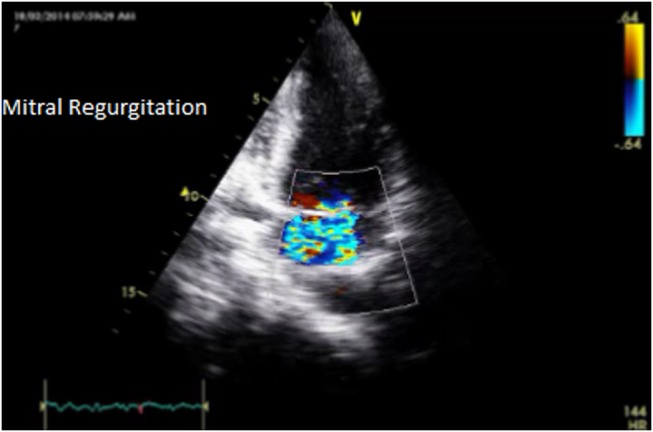

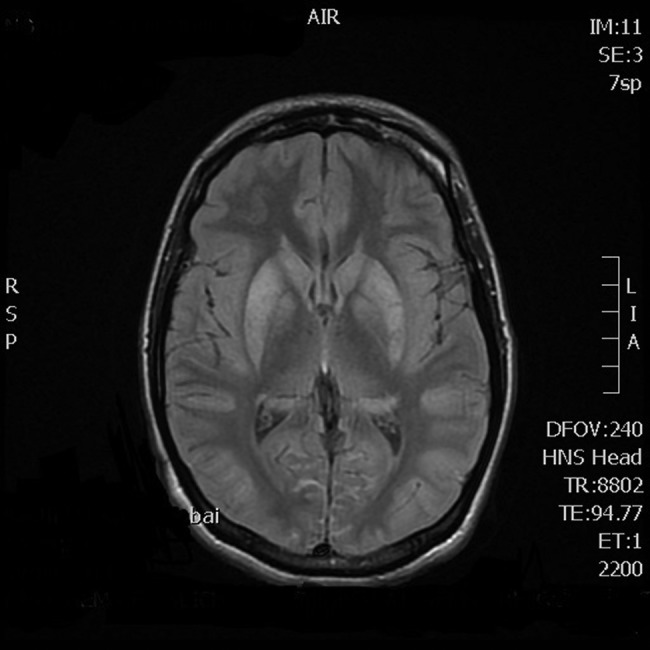

Echocardiogram revealed bileaflet mitral valve prolapse with moderate mitral regurgitation with normal left-ventricular dimensions and ejection fraction of 50% (figures 4 and 5).MRI of the brain showed hyperintensity of bilateral basal ganglia, hippocampi, cerebral peduncles and frontoparietal cortex consistent with hypoxic brain injury (figure 6).

Figure 4.

Echocardiogram bileaflet mitral valve prolapse in long axis apical view.

Figure 5.

Echocardiogram moderate mitral regurgitation with mitral valve prolapse.

Figure 6.

MRI of the brain showing hyperintensity of bilateral basal ganglia, hippocampi, cerebral peduncles and frontoparietal cortex with hypoxic brain injury.

Differential diagnosis

Mitral valve prolapse leading to repolarisation abnormalities

Acquired long QT syndrome secondary to hypocalcaemia or drugs

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Congenital long QT syndrome previously undiagnosed

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Acute coronary syndrome

Treatment

The patient was initially treated with amiodarone and lidocaine infusion for ventricular arrhythmia and then switched to oral amiodarone and bisoprolol. Hypocalcaemia was corrected with intravenous calcium supplements. The patient was started on antiepileptic drugs for myoclonic jerks developed secondary to hypoxic brain injury. Antibiotics were added for a chest infection.

Outcome and follow-up

At the time of writing this report, the patient is off ventilator support with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 7/15. She is haemodynamically stable with no further arrhythmias observed.

Discussion

Mitral valve prolapse is a benign condition caused most commonly by myxomatous degeneration of the valve.1 It is currently defined as the abnormal movement of any part of the mitral valve >2 mm beyond the annular plane in a long axis view in an echocardiogram.2 Some of its complications include mitral regurgitation, infective endocarditis and rarely sudden cardiac death from arrhythmias.1 3

The most common mechanism stated for sudden cardiac death is ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.4–7 The reason for such life-threatening arrhythmias in these patients is, however, still unclear. In a study by Sriram et al,8 a subset of patients characterised by female gender, bileaflet mitral valve billowing and the presence of frequent premature ventricular ectopics are described as more prone to such complications.

Another study by Turker et al9 on 58 patients with mitral valve prolapse showed that the incidence of arrhythmia is increased when accompanied by moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation.

The relationship between electrolyte abnormalities and mitral valve prolapse has been studied to a certain extent. Bobkowski et al10–12 evaluated 113 children with mitral valve prolapse against 101 healthy children and concluded that while arrhythmias were common in the mitral valve prolapse subset, incidence of ventricular arrhythmias is increased when magnesium deficiency is present.

Repolarisation abnormalities have thus been postulated as the possible cause of ventricular arrhythmias.13 Certain studies have noted increased QT-interval dispersion with or without QT-interval prolongation as a predictor of the degree of severity of mitral valve prolapse and subsequently arrhythmias. Such data could possibly help us in risk stratification of patients at high risk for such complications.14–16

In our patient, as mentioned in the literature, several of these risk factors were present—female gender, bileaflet mitral valve prolapse, frequent premature ventricular ectopics, moderate mitral regurgitation and the presence of hypocalcaemia precipitating QT-interval prolongation.

Although rare, the serious nature of these abnormalities stresses the need for further research in this area to prevent its occurrence.

Learning points.

Mitral valve prolapse syndrome can be a cause of sudden ventricular tachyarrhythmia and physicians should be aware of this serious complication.

Patients who present with frequent ventricular premature ectopics need to be evaluated for electrolyte abnormalities.

Patients with episodes of syncope need to be assessed by electrophysiologists for implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors made substantial contribution and were involved in critical appraisal and final approval.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Guy TS, Hill AC. Mitral valve prolapse. Annu Rev Med 2012;63:277–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ; 2006 Writing Committee Members; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2008;118:e523–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayek E, Gring CN, Griffin BP. Mitral valve prolapse. Lancet 2005;365:507–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudoulas H, Schaal SF, Stang JM, et al. Mitral valve prolapse: cardiac arrest with long-term survival. Int J Cardiol 1990;26:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobkowski W, Siwińska A, Zachwieja J, et al. A prospective study to determine the significance of ventricular late potentials in children with mitral valvar prolapse. Cardiol Young 2002;12:333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babuty D, Cosnay P, Breuillac JC, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia factors in mitral valve prolapse. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1994;17:1090–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brzyzkiewicz H, Wałek P, Janion M. [Sudden cardiac arrest in ventricular fibrillation mechanism as a first manifestation of primary mitral valve prolapse]. Przegl Lek 2012;69:1306–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sriram CS, Syed FF, Ferguson ME, et al. Malignant bileaflet mitral valve prolapse syndrome in patients with otherwise idiopathic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:222–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turker Y, Ozaydin M, Acar G, et al. Predictors of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;26:139–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bobkowski W, Siwińska A, Zachwieja J, et al. [Electrolyte abnormalities and ventricular arrhythmias in children with mitral valve prolapse]. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2001;11:125–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bobkowski W, Zachwieja J, Siwińska A, et al. [Influence of autonomic nervous system on electrolyte abnormalities in children with mitral valve prolapse]. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2003;14:220–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobkowski W, Nowak A, Durlach J. The importance of magnesium status in the pathophysiology of mitral valve prolapse. Magnes Res 2005;18: 35–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Digeos-Hasnier S, Copie X, Paziaud O, et al. Abnormalities of ventricular repolarization in mitral valve prolapse. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2005;10:297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zouridakis EG, Parthenakis FI, Kochiadakis GE, et al. QT dispersion in patients with mitral valve prolapse is related to the echocardiographic degree of the prolapse and mitral leaflet thickness. Europace 2001;3:292–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng TO. Increased dispersion of refractoriness in the absence of QT prolongation in patients with mitral valve prolapse and ventricular arrhythmias. Br Heart J 1995;74:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guven B, Eroglu AG, Babaoglu K, et al. QT dispersion and diastolic functions in differential diagnosis of primary mitral valve prolapse and rheumatic mitral valve prolapse. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29:352–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]