Abstract

Objective

To investigate the fauna and seasonal activity of different species of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in Asalouyeh, the heartland of an Iranian petrochemical industry, Southern Iran, as a oil rich district. Sand flies are the vectors of at least three different kinds of disease, the most important of which is leishmaniasis, and it is a major public health problem in Iran with increased annual occurrence of clinical episodes.

Methods

A total of 3 497 sand flies of rural regions were collected by sticky traps fixed, and cleared in puris medium and identified morphologically, twice a month from April to March 2008.

Results

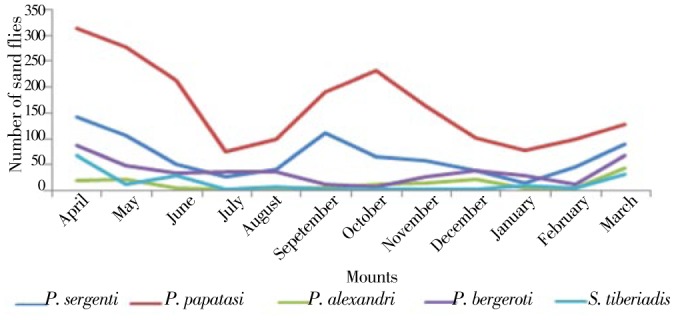

Predominant species included four of genus Phlebotomus (Phlebotomus alexandri Sinton, 1928, Phlebotomus papatasi Scopoli, 1910, Phlebotomus bergeroti Parrot and Phlebotomus sergenti Parrot) and one of genus Sergentomyia (Sergentomyia tiberiadis Alder, Theodor & Lourie, 1930). The most prevalent species was Phlebotomus papatasi, presented 56.4% of the identified flies. The others were Phlebotomus sergenti (22.5%), Phlebotomus alexandri (4.5%), Phlebotomus bergeroti (12%) and Sergentomyia tiberiadis (5%) as well. The percentage of females (68%) was more than that of males (32%). The abundance of sand flies represented two peaks of activity; one in early May and the other one in the first half of September in the region.

Conclusion

Phlebotomus papatasi is the probable vector of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in the region. Further molecular studies are needed to determine the definite vector of the region.

Keywords: Leishmaniasis, Sand flies, Asalouyeh, Bushehr

1. Introduction

Cutaneous leishmainasis is a global public health problem. According to the World Health Organization, cutaneous leishmainasis spreads in 88 different countries and about 12 million people are infected worldwide. Almost 350 million individuals are estimated to be exposed to the disease annually as well[1]. Cutaneous leishmainasis is also considered as an important health concern in Iran with increased annual occurrence of clinical episodes from 220 per 100 000 in 2001 to 350 per 100 000 in 2006[2]. It has been prevalent in several provinces of Iran in the recent decades[3]–[5].

Sand flies are the vectors of leishmaniasis and sand fly fever virus[3]. Leishmania parasites propagate in the gut of female sand fly, as the carriers of leishmania protozoa, and then are directly injected to the skin of human body[6]. However, the infection does not affect the survival of sand fly as well.

Phlebotomus sergenti (P. sergenti) is the only proven vector of cutaneous leishmainasis and laboratory studies have demonstrated the specialty of this species for the protozoan Leishmania tropica[7]. It is distributed from the Canary Islands in Spainto India[8] and is also reported in the neighbor countries including Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Turkmenistan[9].

In the past years, cutaneous leishmainasis was considered to be one of the most important endemic diseases in Shiraz, Mashhad, Isfahan and Bam in Kerman Province[5],[6]. Now days, the diseases are endemic in various cities of Iran including Tehran, Kerman, Shiraz, Isfahan, Boushehr and Mashhad. The prevalence can be observed with increasing human population. In general, the prevalence of cutaneous leishmainasis has been more reported in rural than that of urban areas, and 20-29 years old people are the most susceptible age group to the disease[10].

It should be noted that uncontrolled urban development and population growth are related to sand flies. Changing housing patterns to the apartment in cities does not decrease the incidence of the diseaseamongthe inhabitantsof apartments invarious floors, especially the lowerfloors.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the faunae and monthly activities of sand flies as the vectors of cutaneous leishmainasis. The findings are suggested to be used for the future programs of disease control in Asalouyeh.

2. Materials and methods

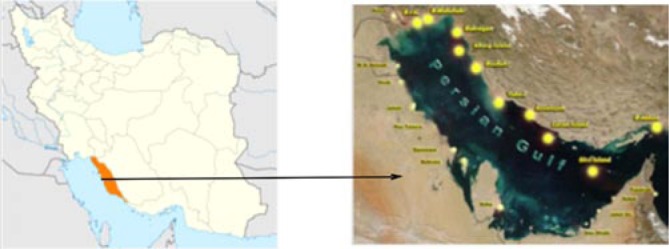

Asalouyeh(27°28′34″ N 52°36′27″ E) is a town of Bushehr Province, Southern Iran, which is located on the shore of the Persian Gulf, southwest of the capital of Bushehr, and is known as the site for the huge PSEEZ (Pars Special Energy Economic Zone) project (Figure 1). Population of about 60 000 inhabitants has been settled or is working in Assaluyeh and Nakhle-Taqi, mostly due to the development of South Pars gas field. Houses are built of concrete and stone in urban and suburban areas of the town.

Figure 1. The map of study area showing Asalouyeh, bushehr Province, Iran.

This study was conducted using sticky paper traps at the first and fifteenth of each month, from April to March 2008, in 4 areas of Asalouyeh. A total of 60 sticky traps were installed either indoor (bedroom and bathroom) or outdoor (gardens and rodent burrows around the village). Traps were set in the holes of the garden walls, in adjacent to the rodent burrows in outdoor places.

Sticky traps (20 cm ×20 cm), coated with castor oil, were placed in each sampling location and left for one night. They were set and collected at sunset and before sunrise the next morning, respectively. Trapping at each temperature and humidity was recorded.

Sand flies were removed from the sticky traps by needle, washed by acetone in a glass containing 70% alcohol and then canned in the puri medium on the slides under the stereomicroscope.

The identification was made by examining the morphology of male genitalia, female spermatheca and pharynges using Theodor and Mesghali systemic identification key[11].

3. Results

A total of 3 497 sand flies (2 594 males and 903 females) were collected from four areas during the study (Table 1). 1 945(55.7%) and 1 552(44.3%) sand flies were hunted from indoor and outdoor regions, respectively (Table 2). After determining the species of sand flies, four species of the genus Phlebotomus [Phlebotomus papatasi (P. papatasi), Phlebotomus alexandri (P. alexandri), Phlebotomus bergeroti (P. bergeroti), P. sergenti] and one species of the genus Sergentomyia [Sergentomyia tiberiadis (S. tiberiadis)] were detected as active ones in the region (Table 1). Most of the specimens of P. papatasi (34.2%), P. sergenti (31.8%) and S. tiberiadis (32.7%) were obtained from Nakhl-taghi (Table 2).

Table 1. Species composition and relative abundance of phlebotomine sand flies in Asalouyeh, Southern Iran 2011.

| Species | Male |

Female |

Total |

|||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |||

| P. sergenti | 524 | 20.2 | 267 | 29.5 | 791 | 22.5 | ||

| P. papatasi | 1536 | 59.2 | 420 | 46.5 | 1956 | 56.0 | ||

| P. alexandri | 99 | 3.8 | 55 | 6.0 | 154 | 4.5 | ||

| P. Bergeroti | 380 | 14.6 | 45 | 4.9 | 425 | 12.0 | ||

| S. Tiberiadis | 55 | 2.1 | 116 | 12.8 | 171 | 5.0 | ||

| Total | 2594 | 903 | 3497 | 100.0 | ||||

Table 2. The geographic and climatic information of collected sand flies in Asalouyeh, Southern Iran, 2011.

| Locality | Species |

ATY | AHY | ||||||||||||||||||

|

P. sergenti |

P. papatasi |

P. alexandri |

P. bergeroti |

S. tiberiadis |

|||||||||||||||||

| Indoor n(%) | Outdoor n(%) | Total n(%) | Indoor n(%) | Outdoor n(%) | Total n(%) | Indoor n(%) | Outdoor n(%) | Total n(%) | Indoor n(%) | Outdoor n(%) | Total n(%) | Indoor n(%) | Outdoor n(%) | Total n(%) | |||||||

| Asalouyeh | 69(37.2) | 116(62.8) | 185(23.3) | 239(56.3) | 145(43.7) | 384(19.6) | 13(38.2) | 21(61.8) | 34(22.0) | 21(35.0) | 39(65.0) | 60(14.11) | 11(30.5) | 25(69.5) | 36(21.0) | 23.5 | 40% | ||||

| Nakhl-taghi | 131(51.9) | 121(48.1) | 252(31.8) | 425(63.4) | 245(36.6) | 670(34.2) | 29(70.7) | 23.5 | 41(26.6) | 19(17.5) | 89(73.5) | 108(25.4) | 25(44.6) | 31(63.4) | 56(32.7) | 23.5 | 40% | ||||

| Shirinoo | 121(61.7) | 75(38.3) | 196(24.7) | 305(60.7) | 137(39.3) | 442(22.5) | 30(61.2) | 23.5 | 49(31.8) | 33(8.7) | 81(91.2) | 114(26.8) | 14(36.8) | 24(63.2) | 38(22.2) | 23.5 | 40% | ||||

| Bidkhoon | 61(38.6) | 97(61.4) | 158(20.0) | 312(60.0) | 138(60.0) | 450(23.0) | 20(66.6) | 23.5 | 30(19.4) | 41(26.7) | 112(33.3) | 153(36.0) | 24(58.5) | 17(41.5) | 41(23.9) | 23.5 | 40% | ||||

| Total | 382(48.2) | 409(51.8) | 791 | 1291(66.0) | 665(34.0) | 1956 | 92(59.7) | 62(40.3) | 154 | 104(24.4) | 321(33.6) | 425 | 74(43.2) | 97(63.7) | 171 | 3497 | |||||

N(%): Number (percentage), ATY: Average of temperature in year, AHY: Average of humidity in year.

In this study was observed significant difference between location and species of sand flies (P<0.05).

The most collected (human and animal) species of sand flies in indoor places was P. papatasi. It was also the most predominant species in all areas and accounted for 56% of the identified flies. 85% and 81% of human and animal species of indoor places was P. papatasi, respectively. The adult sex ratio was 370 males versus 100 females.

P. sergenti, consists of 22.5% of sand flies collected form Asalouyeh, and is considered to be the second abundant species of sand flies collected from the area.

In this period two peaks of activity were observed, including early in May and also in the first half of September; This indicates the two generation period per year is, for the insect (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Monthly abundance of phlebotomine sandflies during April-October, 2009 in Asalouyeh region, Bushehr Province, Iran.

4. Discussion

Faunestic study of sand flies and the vectors of leishmaniasis, seems to be a crucial introduction to many epidemiological and ecological studies. The study of the epidemiology of the leishmaniasis, regardless of considering different aspects of sand flies, is not valuable. The survey results can be applied in making hypothesis of the epidemiology of the disease and the vectors. In this study, 5 species of sand fly were detected, 4 of genus Phlebotomus and one of genus Sergentomyia. This is the first report of faunae and monthly activities of sand flies as the vectors of cutaneous leishmainasis of sand flies in Asaluyeh District. Moreover, the studies conducted by Mesghali (1341), Oshaghi (1368) and Soleimani (1376) in Bastak in Hormozgan Province, near Assaluyeh, reported these five species as well[12],[13]. P. papatasi included 56% of the total sand flies in Asalouyeh, thus is considered to be the dominant species in the region. This species was collected in indoor and outdoor (rodent burrows) places. P. papatasi, collected in indoor places, represents the endophilic property of the kind. Regarding the unknown nature of the parasite in the region as well as the fact that P. papatasi is a known vector of cutaneous leishmainasis in Iran's rural areas[8],[9] and the related leptomonosis infection, reported in Isfahan, Golestan, Khorasan, Khuzestan, Bushehr Provinces[10], this phelebotomus can be most likely the vector of cutaneous leishmainasis in Asalouyeh. The before studies show that 5.6% of P. papatasi infected with leishmania major in Iran[14], which normally prefers to live in plains area rather than in mountains region[15], has been collected from all parts of Iran including Musian District (119 m above level of sea) from both the indoor and outdoor places. Cross and et al. have reported that P. papatasi is the most abundant in areas with mean minimum temperature of 16 °C and maximum temperature of 44 °C from May to October[16]. In a faunistic study in Jask, south of Iran, 8 species (3 Phlebotomus and 5 Sergentomyia) were reported by Azizi and Fekri[17]. Although it is suggested that the certain carriers of the disease to be determined in further studies. Moreover, the role of sand flies in the development of sandfly fever in south-southwest[18] as well as the unknown property of the disease in most parts of Iran, including Asalouyeh, recommend further parasitical studies to be done in this field.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to staff of Asalouyeh Primary Health Care Center, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran.

Comments

Background

Sand flies are the sole vectors of some diseases; leishmaniases are the most important of them. Cutaneous leishmainasis and visceral leishmainasis forms are endemic in some parts of Iran; cutaneous leishmainasis is rapidly spread to almost all provinces of the country.

Research frontiers

Assalouyeh is financially an important region in Iran because of SPEEZ project which is one of the most important fields of gas in the world. Thousands of temporary workers are going to this town; some of them have active ulcers of cutaneous leishmainasis which could be reservoir of parasites for others. Otherwise, no control program will be successful without accurate information on the fauna and biology of vectors.

Related reports

There are numerous articles on the fauna and biology of sand flies and leishmaniasis vectors in many parts of Iran. In almost all of them P. papatasi was the dominant species and primary and proven vector of ZCL.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Apparently this was the only research on the sand flies in Assalouyeh town.

Applications

The results of this research could be used for designing an effective control program of leishmaniasis vectors.

Peer review

This is an ordinary article which gives useful information just on the fauna and some basic biological aspects of leishmaniasis vector (sand flies) in an important Iranian petrochemical gas field, southern Iran.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) [Landscape indicators of health in the Islamic Republic Iran] Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2009. p. 317. Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramalho-Ortigao M, Saraiva EM, Traub-Csekö YM. Sand fly-leishmania interactions: long relationships are not necessarily easy. Open Parasitol J. 2010;4:195–204. doi: 10.2174/1874421401004010195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houghton R, Morkowski S, Stevens Y, Chen J, Moon J, Raychaudhuri S. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies for development of rapid immunoassays for detection of sand fly fever viruses. In: 59th ASTMH Annual meeting. Atlanta, USA. Deerfield: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2010. Nov 3-7, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sand flies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27(2):123–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Orgnzation (WHO) First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases: working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/2010report/en/. [Accessed on 27 December, 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjeux P. Human leishmaniases: epidemiology and public health aspects. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45:267–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;(27):305–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Motazedian MH, Rafizadeh S, Yaghoobi Ershadi MR, et al. Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) alexandri: a probable vector of leishmania infantum in Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100(1):63–68. doi: 10.1179/136485906X78454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javadian E, Nadim A. Studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in Khuzestan, Iran. Part II. The status of sand flies. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1975;68:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alipour H, Yakarim Z, Rasti J, Hasanzadeh J, Neghab M. Status of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Arsanjan County of Fars Iran during a five years (2004-2008) period. In: Joint International Tropical Medicine Meeting (JITM) Bangkok, Thailand: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Büttiker W, Wittmer W. Entomological expedition of the Natural History Museum, Basle to Saudi Arabia. In: Wittmer W, Buttiker W, editors. Fauna of Saudi Arabia. Basel: Ciba-Geigy Ltd; 1979. pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alborzi A, Rasouli M, Shamsizadeh A. Leishmania tropica-isolated patient with visceral leishmaniasisinsouthern Iran. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:306–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gubler DJ. Vector-borne diseases. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 2009;28(2):583–588. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.2.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghbi-ershadi M. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Iran and their role on leishmania transmission. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2012;6:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rassi Y, Hanafi-bojd AA. Sand fly, the vector of leishmaniasis. Tehran, Iran: Noavaran Elm Publication; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cross ER, Newcomb WW, Tucker CJ. Use of weather data and remote sensing to predict the geographic and seasonal distribution of Phlebotomus papatasi in southwest Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:530–536. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azizi K, Fekri S. Fauna and bioecology of sand flies in Jask country, the endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Hormozgan, Iran. Hormozgan Med J. 2011;15:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theodor O, Mesghali A. On the phlebotomine of Iran. J Med Entomol. 1964;1:285–300. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/1.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]