Abstract

A 22-year-old woman first presented in 2009 with abdominal distention. The diagnosis of stage IA right ovarian tumour was made by fertility-sparing surgery. In the subsequent years, the involvement of the left ovary and metastasis to the lungs prompted further surgical intervention and chemotherapy. By 2013, she experienced insidious, debilitating and diffuse musculoskeletal pain with trismus. Polymyositis or diffuse radiculitis was suspected. Imaging studies identified enhancing lesions in the thigh musculature, temporalis, parotid gland, pterygoid, masseter, tongue, cerebellum and leptomeninges. Biopsy of one of the thigh lesions confirmed the diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma. She succumbed to the disease in November 2013. This case illustrates the aggressive nature of mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and its resilience to conventional chemotherapy. On account of its high death rate, it is recommended that the epithelial–mesenchymal transition be researched and early therapy targeted at the k-ras oncogene initiated in spite of the tumour's lower initial staging.

Background

Although ovarian cancer accounts for only 3% of all malignant tumours in women, it is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA.1 Over 100 types of ovarian tumours have been characterised, but the three main types of cancer are derived from the surface epithelium (80%), germ cells (10–15%) or sex cord-stromal cells (5–10%). The epithelial lineage is subdivided further into serous, mucinous, clear cell and endometrioid, each having its unique clinical, pathological and molecular features.2 3 For example, pathological studies have determined that mutations in the K-ras oncogene are more common in mucinous ovarian cancer compared to other subtypes,4 while mutations in the BRCA1 tumour suppressor gene are less common.5

Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC) accounts for approximately 7–14% of invasive ovarian cancer cases,6 7 and in contrast to other epithelial subtypes, it frequently over-expresses the HER-2 antigen.8 It is generally seen in the Asian population who exhibit early stage, low grade and unilateral ovarian involvement. Irrespective of the early stage, mEOC carries a higher death rate than other epithelial ovarian cancers.2 9

A case of a young woman with HER-2 positive mEOC is reported. It is unique, and the first, to the best of our knowledge, to display the aggressive and extensive nature of the epithelial ovarian disease in relation to the musculoskeletal structures, brain parenchyma and visceral organs.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old woman of Philippino descent first presented in 2009 with abdominal pain and distention. She underwent a right salpingo-oophorectomy in 2009 of a 30 cm invasive mucinous ovarian adenocarcinoma, stage IA (figure 1). For staging, the patient underwent periaortic lymph node dissection, peritoneal wash, appendectomy and omentectomy, all of which proved to be free from disease. A limited panel of immunostains was performed at an outside medical facility. The tumour showed strong CK7, and weak and focal CK20 immunoreactivity. Although the CK7/CK20 pattern has a low specificity, it may have been compatible with an ovarian primary. As per reports from the outside institution, an ovarian primary was favoured based on the absence of metastatic disease, negative peritoneal washing, the large size of the tumour, unilateral involvement, morphology (some area with mucinous cystadenoma) and the CK7/CK20 immunoprofile. Observation with serial surveillance pelvic MRI and serum cancer antigen (CA125), β-human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and α-fetoprotein in the absence of adjuvant chemotherapy followed the fertility-sparing surgery.

Figure 1.

Right ovary—invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (H&E stain).

Left oophorectomy was performed a year later because of abdominal distension, MRI findings of a heterogeneous T2 hyperintense 10×11×15 cm pelvic mass abutting the uterus with multiple nodular enhancement, and elevation of CA125 from 5 to 12.5. There was again no evidence of carcinomatosis with negative peritoneal washing, and pathology was consistent with moderately differentiated mucinous ovarian adenocarcinoma. Colonoscopy and mammography were unremarkable. A dose-dense regimen of carboplatin and paclitaxel was administered between July and December 2010. She remained fully functional throughout the treatment.

One year later, a left video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with wedge resection was performed on one of bilateral pulmonary nodules, demonstrating mucinous adenocarcinoma again. Chemotherapy with docetaxel, carboplatin and bevacizumab (Avastin) was given for two cycles. The tumour was shown to possess strong (3+) HER-2 amplification, which prompted a change of bevacizumab to trastuzumab (Herceptin). A total of six cycles of systemic therapy was completed, but the patient developed severe mucositis and onychomadesis (nails falling off). She also had difficulty walking due to pins-and-needles and numbing peripheral neuropathy in the feet, interrupting her college education. Within 6 months, however, she walked without assistance.

Approximately 12 months after the last treatment, there was radiographic progression of the disease. Chemotherapy was postponed by the patient. An aching pain in the right shoulder extending into the neck began in June 2013. Two to three weeks later, the same aching pain appeared in the left shin and right quadriceps. The pain in the right shoulder worsened, especially when lifting or carrying items at work, and eventually becoming unbearable, without relief from oral hydrocodone or oxycodone. In mid-October, 2013, she had difficulty opening her mouth (trismus). Swallowing was preserved.

She was hospitalised for pain management and required parenteral narcotics. Examination revealed limited movement of the jaw laterally and upon opening, but without frank oedema, weakness or atrophy. She displayed multiple tender spots in the legs, back, shoulders and arms, in association with hyperalgesia/allodynia to light touch. Give-way in limb power was noted as a result of pain, and a 1×2 cm mass was palpable proximal to the right patella. There was no heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia or Gottron papules. Deep tendon reflexes were depressed and toes were equivocal to plantar stimulation.

Differential diagnosis

Several possible aetiologies were entertained, including polymyositis, paraneoplastic syndrome, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis and polyradiculitis. Clinical investigation was thus undertaken.

Table 1 illustrates serum values at the time of admission on 16 October 2013. In addition, CA-125 was 50.4 (2–30.1 U/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was 5.1 (0.5–4.9 ng/mL), antinueronal nuclear antibody (ANNA) types 1, 2 and 3 had a negative titre of <1:240 and myositis panel, including Jo 1, PL-7, PL-12, EJ, OJ, KU, was also negative, except for weakly positive MI-2

Table 1.

Serum analysis at the time of admission

| Serum results | Values | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| ANA IgG Ab | None detected | |

| WCC | 9.5 | 3.9–30.1 U/mL |

| RBC | 4.53 | 3.91–5.18 M/μL |

| Haemoglobin | 12.9 | 11.4–15.3 G/dL |

| Platelet | 233 | 126–377 k/μL |

| Total protein | 7.5 | 6.3–8.2 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.3 | 3.5–5.0 g/dL |

| Calcium | 9 | 8.6–10.2 mg/dL |

| SGPT | 190 | 7.56 U/L |

| SGOT | 123 | 15–46 U/L |

| Sodium | 139 | 137–145 mmol/L |

| Glucose | 109 | 80–128 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.36 | 0.6–1 mg/dL |

| Creatine kinase | 118 | 30–135 U/L |

| C reactive protein | 1.3 | <0.8 mg/dL |

| Sedimentation rate | 19 | 0–20 mm/h |

ANA, antineuclear antibody; RBC, red blood cell; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; WCC, white cell count.

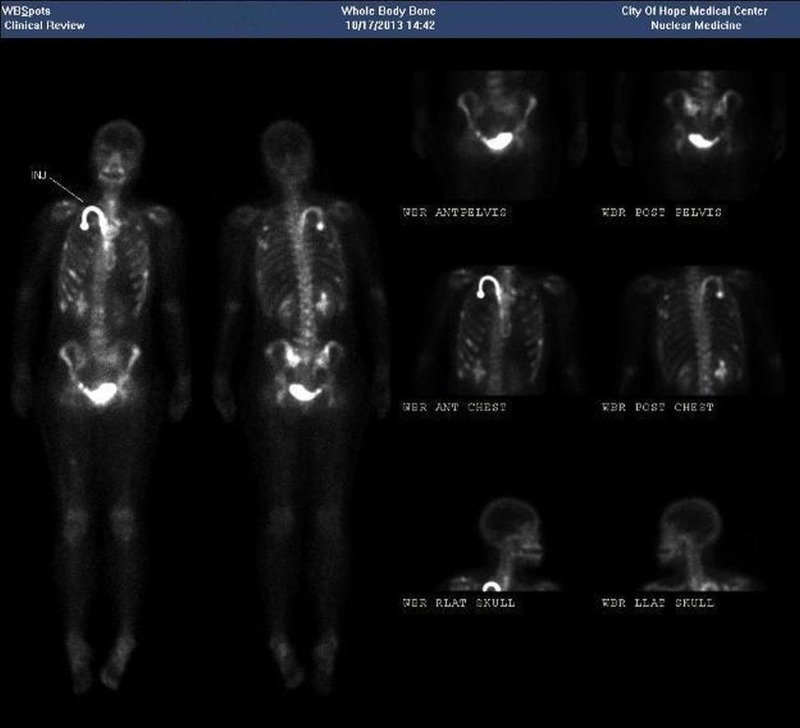

Whole body bone imaging and CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated innumerable abnormal foci within the ribs and pelvis, multiple bilateral pulmonary metastases, some cavitary, as well as hepatic, pancreatic, and left renal metastases (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Whole body bone scan—nuclear uptake is shown within the ribs, pelvis, liver, pancreas and left kidney.

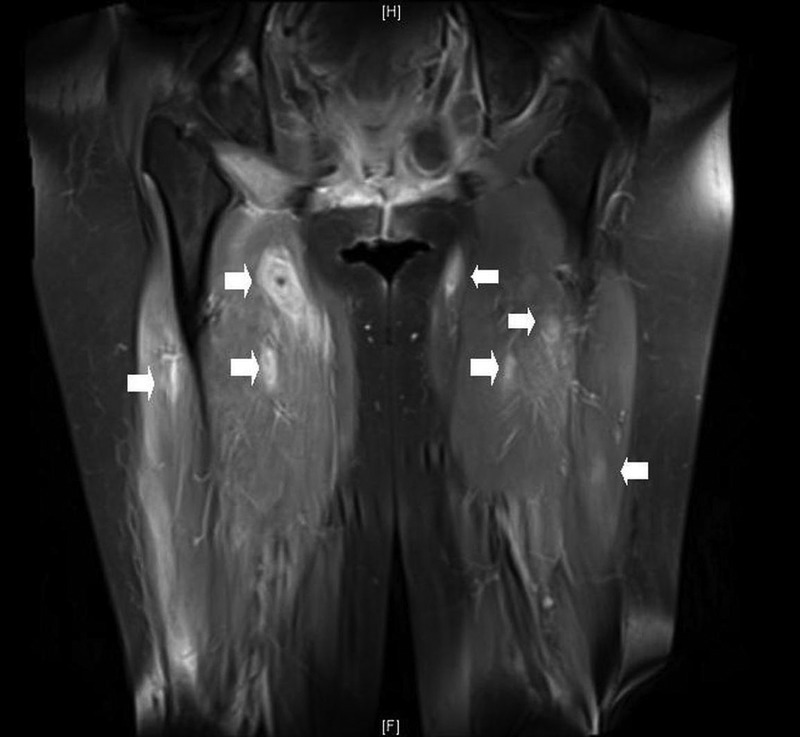

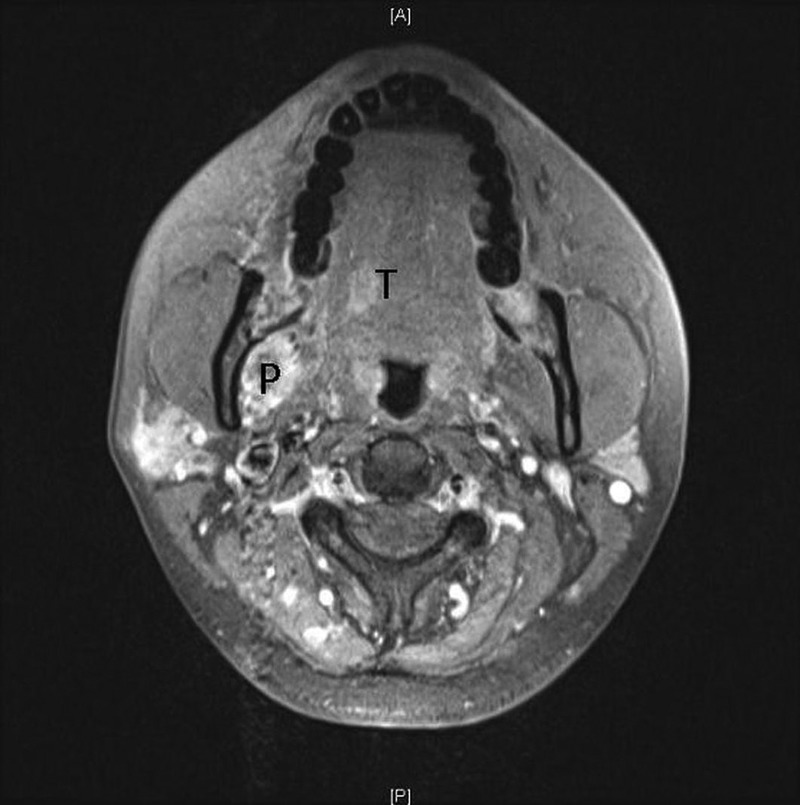

MRI of the bilateral thighs, face and brain was accomplished in the environment of a 3.0 T superconducting magnet using a dedicated extremity surface receiver coil. It showed numerous predominantly nodular and some ring-like enhancing masses in bilateral thigh musculature, with modest T2-weighted hyperintensity and restriction on the diffusion-weighted imaging. Two enhancing masses were demonstrated in the right cerebellum, the largest measuring 13×11 mm with leptomeningeal involvement, right parotid gland measuring 11×8 mm, right pterygoid muscle, left masseter, right posterior lateral tongue and right anterior temporalis muscle (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

MRI sequences (3 T) with gadolinium contrast of the thighs. Arrows indicate multiple enhancing nodules in the rectus femoris and vastus muscles.

Figure 4.

MRI sequences (3 T) with gadolinium contrast of the facial musculature. There is enhancement involving the right pterygoid (P), masseter (lateral to P) and tongue (T).

Limited electrodiagnostic studies (due to pain) revealed demyelinating-axonal neuropathy with acute to subacute denervation on needle electromyography (fasciculation and fibrillation potentials in the right anterior tibialis, right medial gastrocnemius and right posterior tibialis). There was decreased recruitment, but normal firing rate and no clear evidence of myopathic features to suggest polymyositis. The conclusion of probable carcinomatosis polyradiculitis or mononeuritis multiplex was made.

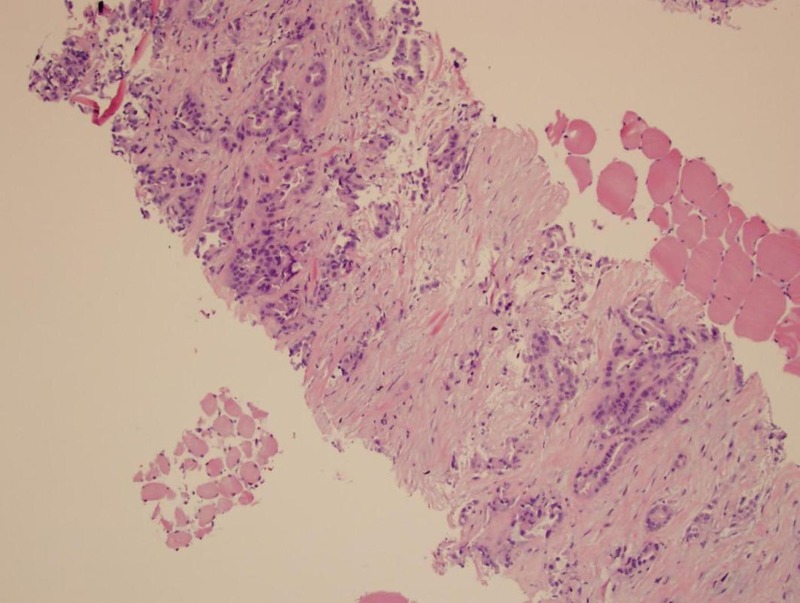

CT-guided needle biopsy of a lesion in the right rectus femoris muscle confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. A panel of immunostains was performed. The tumour showed CK7 immunoreactivity, weak CK20 and PAX8 immunoreactivity (figures 5 and 6), without CDX-2, TTF-1, GCDFP-15, mammaglobin, oestrogen receptor (ER), WT1, MUC2 and p16 immunoreactivity. The immunoprofile did not support colorectal, lung, breast or cervical primary. Compared with the original ovarian tumour, it exhibited similar pathological and immunohistochemical features. It showed a positive (3+) HER-2 gene expression by immunohistochemistry (figure 7).

Figure 5.

Thigh biopsy—metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with primary ovarian cancer (H&E stain).

Figure 6.

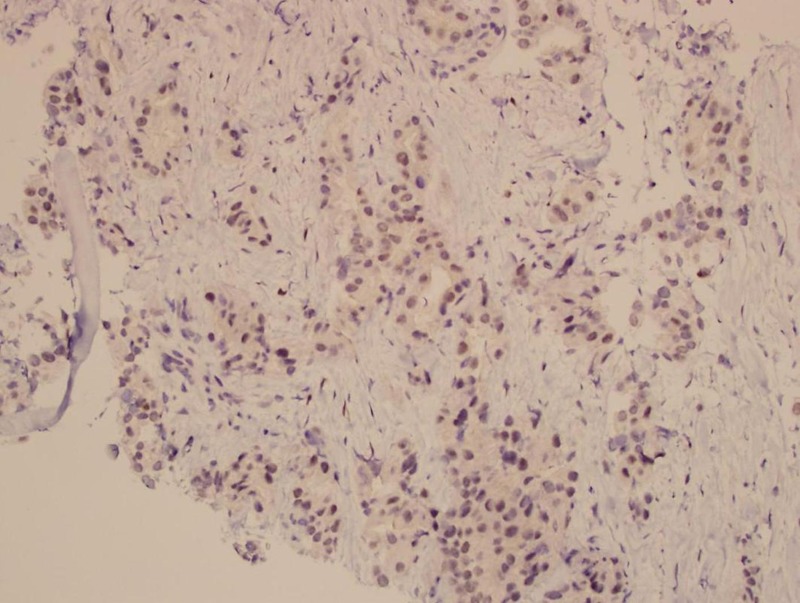

Thigh biopsy—PAX-8 immunohistochemical stain.

Figure 7.

Thigh biopsy—immunohistochemical preparation showing strong (3+) Her-2 expression in the neoplastic cells.

Outcome and follow-up

When pain was adequately controlled with a hydromorphone-based patient controlled analgesia (PCA) pump, she opted to initiate carboplatin and doxorubicin chemotherapy. After the first treatment cycle, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for obstructive jaundice due to a 57 mm metastasis to the distal common bile duct. A right-sided 8.5 French Ring internal/external biliary drain catheter was placed and the patient was released home with palliative care. She expired within a month.

Discussion

Advanced mEOC has been associated with a worse prognosis than the more common serous subtype, chiefly as a result of its highly chemoresistant property.10–12 Typically, mEOC are confined to one ovary, and present with early stage disease (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages I–IIA).13 Less frequently, mEOC is associated with peritoneal or extraperitoneal carcinomatosis. Advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, however, may metastasise throughout the abdominal cavity.14–16 A rare case of gingival metastasis from ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma has been previously reported.17

In pretreated patients, Hynninen et al18 demonstrated with the aid of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) that two-thirds of the cases with advanced EOC had supradiaphragmatic lymph node metastasis, predominately to the cardiophrenic and parasternal lymph nodes.

In order for distant metastasis to occur, the primary cancer must take several steps—from undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (perhaps by the aid of cancer-associated fibroblasts),19 20 to penetrating the stromal matrix, entering the vasculature,21 binding to adhesion and integrin molecules of distant blood vessels,22 exiting the blood vessels, recolonising, expanding, resisting circulatory chemotherapy by coexpression of CD147 with monocarboxylate transporters23 and evading activated immune responses.

For the diagnosis of primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma, a metastasis has to be ruled out clinically. Possible sites include appendix, upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, pancreatobiliary tract, cervix, among others. The importance of immunohistochemistry markers in differentiating ovarian from non-ovarian cancers cannot be overemphasised.

The immunoprofile of the thigh muscle metastasis in this patient shows diffuse and strong CK7 staining and weakly positive CK20 and PAX8, while it shows negative CDX-2, TTF-1, GCDFP15, mammaglobin, ER, WT1, MUC2 and p16. The CK7/CK20 pattern is similar to that of the initial ovarian tumour. The CK7/CK20/CDX-2/MCU2 pattern is not typical for colorectal primary. The negative p16 does not support cervical primary. The negative GCDFP15, mammaglobin and ER argue against breast cancer as the primary tumour. Parenthetically, PAX8 is a transcription factor, crucial for the development of thyroid gland, kidney and the Müllerian system. It is a useful marker in discriminating ovarian carcinomas from non-gynaecological cancers.24 25 Although not typical, PAX 8 reactivity has been reported to be positive in up to 50% of ovarian mucinous carcinoma.26

To the best of our knowledge, this is a first reported case of mEOC with metastases to various musculoskeletal structures. Like other advanced mucinous tumours, chemoresistance seems to be the rule. Epigenetic modification and proteomic research into the epithelial-mesenchymal transition may herald targeted treatment options in the future for such individuals.

Learning points.

Recurrent metastatic mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC) to the musculoskeletal system is an unusual manifestation of the disease.

Resistance to conventional chemotherapy is the norm for mEOC.

Aggressive and early targeted therapy and close longitudinal surveillance should be considered in spite of the tumour's lower staging at the time of diagnosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: JZ provided the second most aid, followed by RM and the least NP.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2010 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/uscs [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess V, A'Hern R, Nasiri N, et al. Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: a separate entity requiring specific treatment. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1040–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vereczkey I, Serester O, Dobos J, et al. Molecular Characterization of 103 Ovarian Serous and Mucinous Tumors. Pathol Oncol Res 2011;17:551–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gemignani ML, Schlaerth AC, Bogomolniy F, et al. Role of KRAS and BRAF gene mutations in mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:378–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakhani SR, Manek S, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1and BRCA2 carriers. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:2473–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire V, Jesser CA, Whittemore AS. Survival among US women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2002;84:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quirk JT, Natarajan N. Ovarian cancer incidence in the United States, 1992–1999. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:519–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anglesio MS, Kommoss S, Tolcher MC, et al. Molecular characterization of mucinous ovarian tumours supports a stratified treatment approach with HER2 targeting in 19% of carcinomas. J Pathol 2013;229:111–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M, et al. The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:41–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandre J, Ray-Coquard I, Selle F, et al. Mucinous advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma: clinical presentation and sensitivity to platinum–paclitaxel-based chemotherapy, the GINECO experience. Ann Oncol 2010;21:2377–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karabuk E, Faruk Kose M, Hizli D, et al. Comparison of advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and serous epithelial ovarian cancer with regard to chemosensitivity and survival outcome: a matched case-control study. J Gynecol Oncol 2013;24:160–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pectasides D, Fountzilas G, Aravantinos G, et al. Advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:436–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet 2001;357:176–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadia A, Morotti M. Diaphragmatic surgery during cytoreduction for primary or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287:733–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain A, Ryan PD, Seiden MV. Metastatic mucinous ovarian cancer and treatment decisions based on histology and molecular markers rather than the primary location. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:1076–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sher–Ahmed A, Buscerna J, Sardi A. A case report of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer metastatic to the sternum, diaphragm, costae, and bowel managed by aggressive secondary cytoreductive surgery without postoperative chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 2002;86:91–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki H, Ohara N, Minamikawa T, et al. Gingival metastasis from ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma as an initial manifestation (a rare case report). Kobe J Med Sci 2008;54:E174–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hynninen J, Auranen A, Carpen O, et al. FDG PET/CT in staging of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: frequency of supradiaphragmatic lymph node metastasis challenges the traditional pattern of disease spread. Gynecol Oncol 2012;126:64–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson EW, Newgreen DF. Carcinoma invasion and metastasis: a role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition? Cancer Res 2005;65:5991–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Tang H, Zhang T, et al. Ovarian cancer-associated fibroblasts contribute to epithelial ovarian carcinoma metastasis by promoting angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis and tumor cell invasion. Cancer Lett 2011;303:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Steeg PS. Cancer invasion and metastasis: positive and negative regulatory elements. Cancer Invest 1991;9:543–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabriel B, Mildenberger S, Weisser CW, et al. Focal adhesion kinase interacts with the transcriptional coactivator FHL2 and both are overexpressed in epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res 2004;24:921–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, Wang L, Beretov J, et al. Co-expression of CD147/EMMPRIN with monocarboxylate transporters and multiple drug resistance proteins is associated with epithelial ovarian cancer progression. Clin Exp Metastasis 2010;27:557–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nonaka D, Chiriboga L, Soslow RA. Expression of pax8 as a useful marker in distinguishing ovarian carcinomas from mammary carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1566–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiwara M, Taube J, Sharma M, et al. PAX8 discriminates ovarian metastases from adnexal tumors and other cutaneous metastases. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:938–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ordonez NG. Value of PAX 8 immunostaining in tumor diagnosis: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol 2012;19:140–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]