Abstract

Objective

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) is a clinical diagnosis characterised by progressive lower motor neuron (LMN) symptoms/signs with sporadic adult onset. It is unclear whether PMA is simply a clinical phenotype of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in which upper motor neuron (UMN) signs are undetectable. To elucidate the clinicopathological features of patients with clinically diagnosed PMA, we studied consecutive autopsied cases.

Design

Retrospective, observational.

Setting

Autopsied patients.

Participants

We compared clinicopathological profiles of clinically diagnosed PMA and ALS using 107 consecutive autopsied patients. For clinical analysis, 14 and 103 patients were included in clinical PMA and ALS groups, respectively. For neuropathological evaluation, 13 patients with clinical PMA and 29 patients with clinical ALS were included.

Primary outcome measures

Clinical features, UMN and LMN degeneration, axonal density in the corticospinal tract (CST) and immunohistochemical profiles.

Results

Clinically, no significant difference between the prognosis of clinical PMA and ALS groups was shown. Neuropathologically, 84.6% of patients with clinical PMA displayed UMN and LMN degeneration. In the remaining 15.4% of patients with clinical PMA, neuropathological parameters that we defined as UMN degeneration were all negative or in the normal range. In contrast, all patients with clinical ALS displayed a combination of UMN and LMN system degeneration. CST axon densities were diverse in the clinical PMA group, ranging from low values to the normal range, but consistently lower in the clinical ALS group. Immunohistochemically, 85% of patients with clinical PMA displayed 43-kDa TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) pathology, while 15% displayed fused-in-sarcoma (FUS)-positive basophilic inclusion bodies. All of the patients with clinical ALS displayed TDP-43 pathology.

Conclusions

PMA has three neuropathological background patterns. A combination of UMN and LMN degeneration with TDP-43 pathology, consistent with ALS, is the major pathological profile. The remaining patterns have LMN degeneration with TDP-43 pathology without UMN degeneration, or a combination of UMN and LMN degeneration with FUS-positive basophilic inclusion body disease.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The characteristics of motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or progressive muscular atrophy were comprihensively described.

The severity of upper motor neuron involvement was semiquantitatively compared between the clinical groups, and quantitatively surrogated by axonal densities in the corticospinal tract.

Pathological results clearly indicated the differences of upper motor neuron involvement between the clinical groups.

To evaluate the entire regions in the motor cortex or the corticospinal tract is not possible.

We prepared formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues to quantificate axonal densities in the corticospinal tract. In this protocol, the tissues can be distorted compared with the conventional fixation using glutaraldehyde and Epon. The results can vary more than those from other histological techniques.

Introduction

Motor neuron disease (MND) constitutes a group of heterogeneous neurodegenerative diseases that are associated with progressive upper motor neuron (UMN) and/or lower motor neuron (LMN) degeneration. A portion of MND cases has genetic causes; however, the majority of MND cases are sporadic and of unknown aetiology. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) constitutes the majority of MND cases. ALS is a clinicopathological disorder that presents with progressive UMN and LMN symptoms/signs. Neuropathologically, the UMN and LMN systems exhibit neuronal loss and gliosis and Bunina bodies are detected in surviving neurons. Although various immunohistochemical profiles have been identified in patients with ALS, 43-kDa TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) is the major pathological protein in sporadic ALS.1

In contrast, MND that presents with LMN symptoms/signs alone occurs in several disorders, including genetically mediated disorders such as, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), symmetrical axonal neuropathy and spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA).2 3 Additionally, a sporadic and adult-onset LMN disease has been referred to as progressive muscular atrophy (PMA).3 4 Although the revised El Escorial criteria, the standard diagnostic criteria for ALS, exclude patients who only present with LMN symptoms/signs, several studies have revealed that a subset of patients with clinically diagnosed PMA exhibit the neuropathological hallmarks of ALS. Postmortem histopathological studies have revealed corticospinal tract (CST) degeneration in more than half of the patients with MND clinically limited to LMN symptoms/signs.5 6 TDP-43-immunoreactive inclusions have been detected in the LMNs and cortical neurons of patients with PMA.7 8 The disease course of PMA is relentlessly progressive, although somewhat longer than that of ALS.2 4 9 10

However, it is unclear whether clinically diagnosed PMA is simply a clinical phenotype of ALS in which UMN symptoms/signs are undetectable. In this study, we investigated the clinicopathological profiles of patients with clinically diagnosed PMA compared with those of patients with clinically diagnosed ALS using a series of consecutive adult-onset sporadic MND autopsy cases.

Methods

Patients and clinical evaluations

We enrolled 130 consecutive autopsied patients who were clinically diagnosed with and pathologically confirmed as suffering from sporadic, adult-onset MND at the Department of Neuropathology of the Institute for Medical Science of Aging at the Aichi Medical University from January 1998 to December 2010. All of the patients had been clinically evaluated by neurological experts at the Nagoya University Hospital, the Aichi Medical University Hospital or their affiliated hospitals. Permission to perform an autopsy and archive the brain and spinal cord for research purposes was obtained from the patients’ relatives by the attending physician after death. We evaluated the clinical profiles of the included patients by retrospectively reviewing case notes written at the time of diagnosis and in an advanced disease stage. Disease onset was defined as the time at which patients became aware of muscle weakness. The inclusion criteria for the patients with MND were as follows: older than 18 years at disease onset; no family history of ALS, PMA, progressive lateral sclerosis, inherited SMA or SBMA or any other neurodegenerative disorder; motor neuron involvement based on neurological examination and neuropathological evidence of neuronal loss and gliosis in the UMN and/or LMN systems that were not due to any cerebrovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, genetic neurological disorders, inflammatory disorders, neoplasms or traumas. We excluded 22 patients due to invalid clinical data and 1 patient with only UMN symptoms/signs throughout his disease course; 107 patients were ultimately included in this study. Based on the clinical data, we separated these 107 patients with MND into two groups, namely the clinical PMA and clinical ALS groups. According to a previous study,4 clinical PMA was defined by neurological evidence of LMN involvement (decreased or diminished deep tendon reflexes and muscle atrophy) and a lack of UMN symptoms/signs (increased jaw jerk, other exaggerated tendon reflexes, Babinski sign, other pathological reflexes, forced crying and forced laughing) throughout the clinical course. Patients who exhibited motor conduction block(s) based on extensive standardised nerve conduction studies,11 exhibited objective sensory signs (apart from mild vibration sensory disturbances in elderly patients) or had a history of diseases that may mimic MND (eg, spinal radiculopathy, poliomyelitis and diabetic amyotrophy) were not included in the clinical PMA group.4 We defined clinical ALS, based on the revised El Escorial criteria, as fulfilling ‘possible’ or above categories, which require UMN signs/symptoms in at least one region of the body.12

Pathological evaluations

For pathological evaluations, we excluded one patient with clinical PMA due to severe anoxic changes in the brain and four patients with clinical ALS due to insufficient tissue material. Ultimately, we enrolled 13 patients with clinical PMA for pathological evaluations. For comparison, we enrolled 29 patients with clinical ALS who were consecutively autopsied during the past 5 years of the study period (after January 2006). Additionally, 13 age-matched controls (mean age at death 68±6.91 years) were enrolled. We prepared 8 mm coronal sections of the cerebrum and 5 mm axial sections of the brainstem. The tissues were fixed using 20% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4.5 μm. We evaluated the sections from the precentral gyrus (four segments from the left hemisphere), hippocampus, brainstem and spinal cord. In all cases, the spinal cord was examined at all segment levels. Two investigators (YR and MY) evaluated the degeneration of the motor neuron systems and the immunohistochemical profiles of the included patients. The investigators were completely blinded to each patient's ID and the clinical diagnosis corresponding to each specimen. With respect to the degeneration of motor neuron systems, the severity of motor neuron loss in the primary motor cortex, facial and hypoglossal nuclei and spinal anterior horns, myelin pallor within the CST and aggregation of macrophages within the primary motor cortex and CST were evaluated. The evaluations were performed on the most severely affected lesions and graded as none (−), mild (+), moderate (++) or severe (+++; figure 1). The immunohistochemical profiles were evaluated using anti-pTDP-43 and antifused-in-sarcoma (FUS) antibodies in the LMN system and cerebrum. For the routine neuropathological examinations, the sections were subjected to H&E or Klüver-Barrera staining. Immunohistochemistry was performed according to a standard polymer-based method using the EnVision Kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The primary antibodies used in this study were antiubiquitin (polyclonal rabbit, 1:2000; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-TDP-43 (polyclonal rabbit, 1:2500; ProteinTech, Chicago, Illinois, USA), antiphosphorylated TDP-43 (pTDP-43 ser 409/410, polyclonal rabbit, 1:2500; CosmoBio, Tokyo, Japan), anti-FUS (polyclonal rabbit, 1:500; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA), anti-α internexin (monoclonal mouse, 1:1000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA), antiperipherin (polyclonal rabbit, 1:200; Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA), anti-CD68 (monoclonal mouse, 1:200; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), antiphosphorylated neurofilament (pNF, monoclonal mouse, 1:600; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and parvalbumin (polyclonal mouse, 1:1000; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA). Diaminobenzidine (Wako, Osaka, Japan) was used as the chromogen.

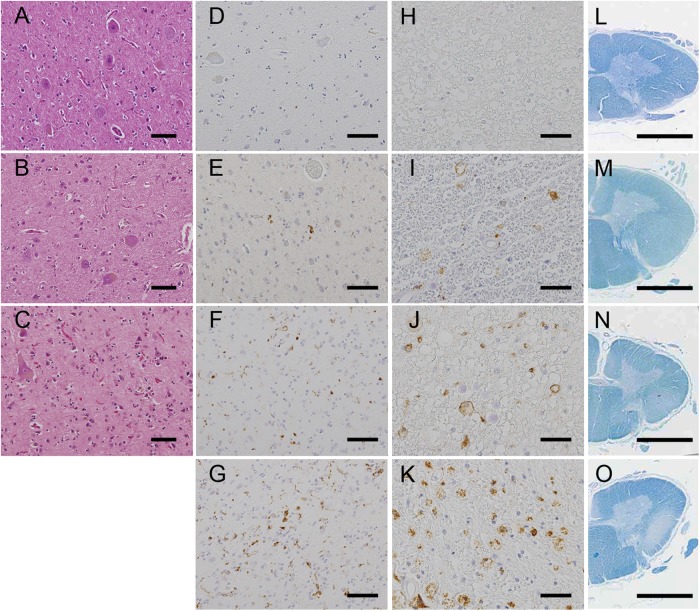

Figure 1.

Measures of degeneration in the upper motor neuron system. (A–D) Loss of Betz cells in the primary motor cortex: stage (−), the Betz cells were spared in number and gliosis was absent (A); stage (+), mild neuronophagia and gliosis were noted (B) and stage (++), marked neuronophagia and glial proliferation were observed (C). (D–K) Aggregation of CD68 macrophages in the primary motor cortex (D–G) and the corticospinal tract in the lateral column of the spinal cord (H–K): stage (−), the aggregates were absent (D and H); stage (+), the aggregates were occasionally present (E and I); stage (++), the aggregates were present at a number of 1–5/ ×100 field (F and J) and stage (+++), the aggregates were diffusely observed (G and K). (L–O) Myelin pallor in the corticospinal tracts (CST) of the lateral column of the spinal cord: stage (−), myelin pallor was not detected (L); stage (+), myelin pallor was slightly notable (M); stage (++), myelin pallor was moderate (N) and stage (+++), the CST was entirely pale. (A–C) H&E staining, (D–K) anti-CD68 immunohistochemistry and (L–O) Klüver-Barrera staining. Scale bars: (A–G) 100 μm, (H–K) 50 μm and (L–O) 3 mm.

Quantitative analysis of large axonal fibres in the CST

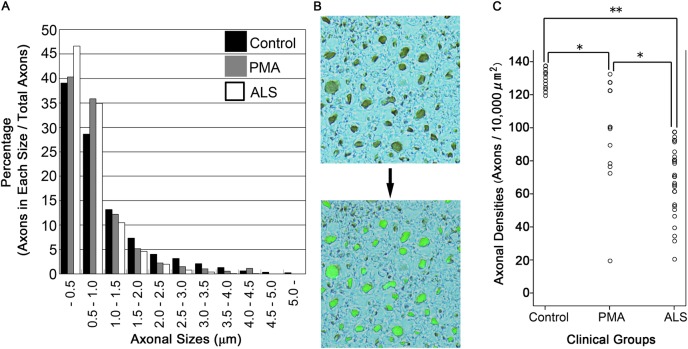

To evaluate the degeneration of axonal fibres in the CST, we calculated the density of axonal fibres in the lateral column of the spinal cord. Specimens corresponding to the C5–6 levels were prepared for all of the patients and 13 controls. For this assay, the paraffin-embedded spinal cords were immunostained using the anti-pNF antibody and diaminobenzidine as chromogen without additional nuclear staining to visualise only axons as brown particles. The microscopic views were binarised and automatically recognised using Luzex AP software (Nireco, Tokyo, Japan) that was coupled to the microscope via a CCD video camera. This software automatically measured the particle counts and diameters on the binarised pictures.13 Axonal counts were evaluated on five areas of 10 000 μm2 (×40 objective) randomly chosen from the CST of the spinal lateral column in each patient and averaged. To validate duplicability between tests, we constructed two axon size histograms from 13 ipsilateral control samples (see online supplementary file). Briefly, the variability between the test and retest was sufficiently small to count the axons for each axon size. We constructed a histogram of axonal sizes in the CST (figure 2A), and the density of the large axons (axonal fibres/10 000 μm2) was calculated (figure 2B,C) for patients with PMA and ALS and control samples.

Figure 2.

Quantitative analysis of the axonal fibres in the corticospinal tract. (A) Phosphorylated neurofilament (pNF)-positive fibres were automatically binarised using Luzex AP software. The density of pNF-positive axons (particles/10 000 μm2) was automatically calculated using averaged data from five fields (×400). The histogram of axonal sizes revealed that the percentages of axons that were more than 1 μm in diameter were smaller in ALS and PMA than in controls. (B) The large axonal fibres more than 1 μm in diameter were automatically recognised, binarised and counted using the software to successfully evaluate the axonal density. (C) There were significant differences in the densities of axons that were more than 1 μm in diameter between all pairs of clinical groups: p=0.001 (*) between the clinical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and clinical progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) groups, p=0.001 (*) between the clinical PMA and control groups and p<0.001 (**) between the clinical ALS and control groups. All patients diagnosed with clinical ALS exhibited lower values than the controls. In contrast, the results of the clinical PMA group were widely diverse, ranging from low values to values within the normal range.

Statistical analysis

The demographic features of patients with PMA and ALS were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables or the Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test to assess bivariate correlations. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for analyses between three groups, and the t test was used for analyses between two groups. The significance level was set at a p value of 0.05 for comparisons between two groups and 0.016 for comparisons between three groups. All of the statistical tests performed were two-sided and were conducted using the software program PASW V.18.0 (IBM SPSS).

Results

Demographic features of the registered patients

The included patients consisted of 67 men and 40 women. The mean age at disease onset was 62.7±12.4 years, and the median duration from disease onset to death was 27 months (range 2–348 months). Seventeen patients were treated with tracheostomy positive-pressure ventilation (TPPV). Initial symptoms included upper limb weakness in 40.2%, lower limb weakness in 32.7%, bulbar symptoms in 24.3% and respiratory symptoms in 2.8% of the included patients. Fourteen (13.1%) patients were categorised into the clinical PMA group, and 93 (86.9%) patients were classified into the clinical ALS group. With regard to clinical diagnosis, 10 (71.4%) of 14 patients with clinical PMA and 88 (94.6%) of 93 patients with clinical ALS were correctly diagnosed as PMA or ALS by the first referred physicians. However, one patient with clinical PMA and four patients with clinical ALS were initially diagnosed as having cervical or lumbar canal stenosis based on focal weakness restricted to one upper or lower limb and canal stenosis on MRI. One of the patients with clinical PMA was initially diagnosed as having carpal tunnel syndrome based on weakness restricted to the distal area of the median nerve in the right hand. One of the patients with clinical PMA was diagnosed as having polyradiculopathy because the cauda equina was slightly enhanced on gadolinium-enhanced MRI. One of the patients with clinical PMA was initially diagnosed as having myositis based on myalgia and slight lymphatic infiltration on a muscle biopsy. One of the patients with clinical ALS was initially diagnosed as having parkinsonian syndrome because the patient showed bradykinesia due to marked rigospasticity in the limbs. The demographic features of patients with clinical PMA and ALS are presented in table 1. In summary, no significant differences in the age at onset, male-to-female ratio, clinical duration (whether including or excluding the TPPV treatment period) or initial symptoms were detected between the clinical PMA and ALS groups.

Table 1.

Demographic features of clinical patients with PMA and ALS

| Clinical PMA | Clinical ALS | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 14 | 93 | |

| Age at onset (years, mean±SD) | 60.8±10.8 | 63.0±12.7 | 0.388* |

| Male/female | 10/4 | 57/36 | 0.563† |

| Duration from onset to death (months; median, range)‡ | 21 (5–192) | 29 (2–348) | 0.764* |

| Initial symptoms (number of patients) | |||

| Bulbar symptoms | 3 (21.4%) | 23 (24.7%) | 0.738† |

| Upper limb weakness | 5 (35.7%) | 38 (40.9%) | 0.738† |

| Lower limb weakness | 5 (35.7%) | 30 (32.3%) | 0.738† |

| Respiratory symptoms | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

*Mann-Whitney U test.

†Fisher's exact test.

‡Including the TPPV treatment period.

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; PMA, progressive muscular atrophy; TPPV, tracheostomy positive-pressure ventilation.

Pathological evaluations

Degeneration in the UMN system

Loss of Betz cells in the primary motor cortex

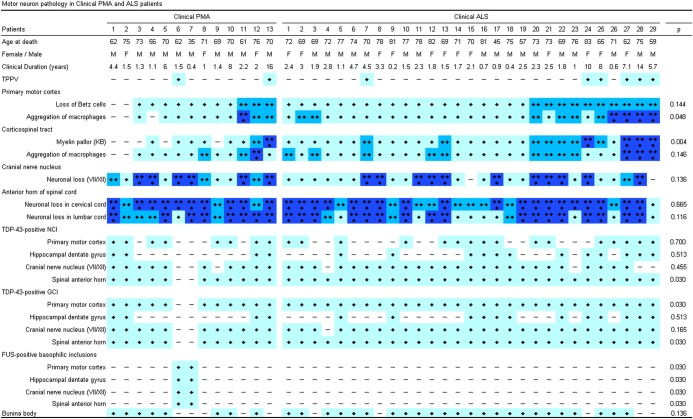

Ten (76.9%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA exhibited a loss of Betz cells, which was severe in 3 (23.1%) of these patients (figure 3). However, in 2 (15.4%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA, no loss of Betz cells or gliosis in the primary motor cortex was detectable. In contrast, all of the patients diagnosed with clinical ALS exhibited a loss of Betz cells, which was severe in 10 (34.5%) of the 29 patients with clinical ALS. There was no significant difference in the severity of this pathological change between the clinical groups.

Figure 3.

Summary of the neuropathological findings in the included patients. The stages of the pathological changes correspond to those in figure 1. Pathological changes between the clinical groups were compared using Pearson's χ² test. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; FUS, antifused-in-sarcoma; GCI, glial cytoplasmic inclusions; KB, Klüver-Barrera staining; NCI, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion; PMA, progressive muscular atrophy; TDP-43, 43 kDa TAR DNA-binding protein; TPPV, tracheostomy positive-pressure ventilation.

Aggregation of macrophages in the primary motor cortex

The aggregation of CD68 macrophages in the primary motor cortex was detected in 10 (76.9%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA. In contrast, all of the patients diagnosed with clinical ALS exhibited the aggregation of macrophages in the primary motor cortex. When comparing the clinical groups, this pathological change was significantly more severe in clinical ALS than clinical PMA (p=0.048).

CST degeneration

Myelin pallor was present in 8 (61.5%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA. The aggregation of macrophages within the CST was detected in 11 (84.6%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA. In the clinical ALS group, all patients exhibited myelin pallor and macrophage aggregation in the CST. When comparing the clinical groups, this pathological change was significantly more severe in clinical ALS than clinical PMA (p=0.004).

Degeneration in the LMN system

All of the patients diagnosed with either clinical PMA or ALS exhibited neuronal loss in the spinal anterior horns (figure 3). This neuronal loss was severe in 11 (84.6%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA and 20 (69%) of the 29 patients with clinical ALS. All of the patients diagnosed with clinical PMA and 27 (93.1%) of the 29 patients with clinical ALS exhibited neuronal loss in the cranial nerve nuclei. This neuronal loss was severe in 6 (46.2%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA and 11 (37.9%) of the 29 patients with clinical ALS. When comparing the clinical groups, there was no significant difference in the severity of LMN loss. Eight (61.5%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA and 24 (82.8%) of the 29 patients with clinical ALS displayed Bunina bodies in the LMN system.

Immunohistochemical profiles

In 11 (84.6%) of the patients with clinical PMA, we detected ubiquitin and TDP-43-positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCIs) in the LMN system (figure 3). In eight of these patients, TDP-43-positive NCIs were also detected in the primary motor cortex. All of the patients with clinical ALS displayed ubiquitin and TDP-43-positive NCIs in the LMN system. Moreover, TDP-43-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions were observed in the spinal anterior horn and primary motor cortex in all of the TDP-43-positive patients of the clinical ALS and PMA groups. In contrast, two of the patients with clinical PMA (15.4%) exhibited basophilic inclusion bodies in the neuronal cytoplasm, which were broadly extended throughout the central nervous system. These inclusions were positive for FUS but negative for TDP-43, α-internexin and peripherin.

Quantitative analysis of large axonal fibres in the CST

The histogram of axonal sizes revealed that the percentage of axons that were greater than 1 μm in diameter was smaller in ALS (18.5%) and PMA (23.9%) than in controls (32.3%), resulting in a relative increase in the percentage of smaller axons (figure 2). Then, we measured the densities of large axons that were greater than 1 μm in diameter. The average densities were as follows: clinical ALS, 68.3±20.9 fibres/10 000 μm2; clinical PMA, 97.2±31.5 fibres/10 000 μm2 and controls, 129.1±6.1 fibres/10 000 μm2 (p=0.001 between the clinical ALS and PMA groups; p=0.001 between the clinical PMA and control groups; p<0.001 between the clinical ALS and control groups). All patients diagnosed with clinical ALS exhibited lower values than the range of normal values that was obtained from the controls. In contrast, the results from the clinical PMA group were widely diverse. The results from 5 (38.5%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA were within the normal range, but 8 (61.5%) of these patients exhibited lower values than the normal range. One patient with PMA who had been treated with TPPV exhibited an exceptionally low value.

Pathological overview of the patients diagnosed with clinical PMA or clinical ALS

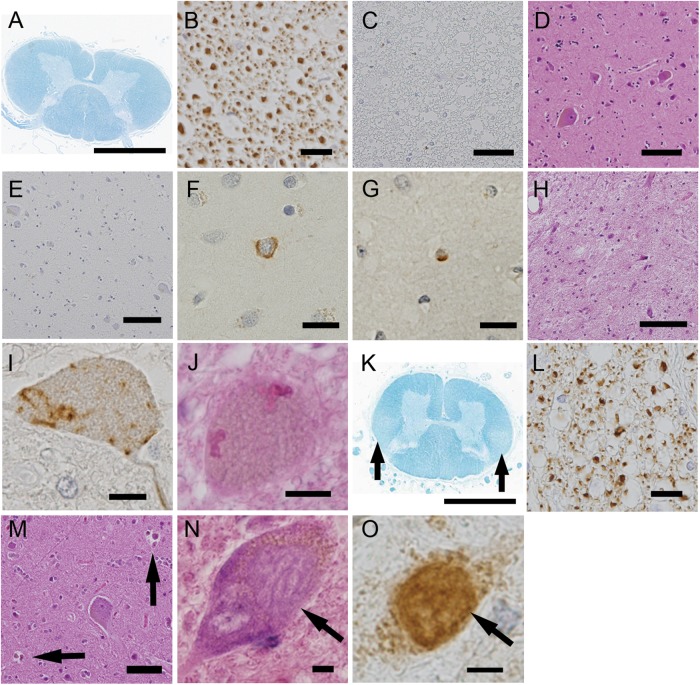

Clinical PMA: 11 (84.6%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA displayed UMN degeneration (either the loss of Betz cells, myelin pallor or the aggregation of macrophages in the primary cortex or CST) and LMN degeneration. Nine of these patients exhibited TDP-43-positive inclusions and the remaining 2 patients displayed FUS-positive basophilic inclusion bodies. Their large CST axon densities were diverse, ranging from low values to values within the normal range that were obtained from the control participants. In 2 (15.4%) of the 13 patients with clinical PMA, neuropathological parameters that we defined as UMN system degeneration were all negative. Their large CST axon density was within the normal range. These two patients exhibited abundant TDP-43-positive neuronal and glial inclusions in the LMN and, occasionally, in layers II–III of the primary motor cortex and the hippocampus. The pathological findings from the representative patients are shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Neuropathological profiles of the patients in the clinical progressive muscular atrophy group. (A–J) correspond to patient 2. The corticospinal tracts (CST) did not display myelin pallor (A), loss of large axonal fibres (B), or aggregation of macrophages (C). Additionally, in the primary motor cortex, neither the loss of Betz cells (D) nor aggregation of macrophages (E) was detected. The upper layers of the primary motor cortex rarely contained phosphorylated 43 kDa TAR DNA-binding protein (pTDP-43)-positive neuronal (F) and glial (G) inclusions. The spinal anterior horn displayed severe neuronal loss (H), pTDP-43-positive skein-like inclusions (I) and Bunina bodies (J). (K–M) correspond to patient 12. The CST displayed myelin pallor (K) and the depletion of large axonal fibres (L). Neuronophagia was often found in the primary motor cortex (M, arrows). (N and O) correspond to patient 6. The spinal motor neurons contained basophilic inclusion bodies (N) that were positive for antifused-in-sarcoma (FUS) based on immunohistochemistry (O). (A and K) Klüver-Barrera staining, (B) antiphosphorylated neurofilament immunohistochemistry, (C and E) anti-CD68 immunohistochemistry, (D, H, J and M) H&E staining, (F, G and I) anti-pTDP-43 immunohistochemistry and (O) anti-FUS immunohistochemistry. Scale bars: (A and K) 3 mm, (D and E) 100 μm, (C, H and M) 50 μm, (B) 20 μm and (F, G, I, J, N and O) 10 μm.

Clinical ALS: All 29 patients displayed a combination of UMN and LMN system degeneration and exhibited TDP-43-positive inclusions.

Additionally, of the respirator-managed patients, three patients (patient 13 of clinical PMA and patients 27 and 28 of clinical ALS) showed diffusely extended neuronal loss, gliosis and TDP-43 pathology beyond the motor neuron systems, which involved all layers of the cerebral neocortices, the striatum, thalamus, cerebellar dentate nucleus and non-motor nuclei in the brainstem, including the substantia nigra, red nucleus, periaqueductal grey matter, inferior olivary nucleus and reticular formation.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the clinicopathological profiles of patients with clinical PMA and ALS in a consecutive autopsy series. The clinical evaluations in this study revealed rapid disease progression and short survival duration in patients with clinical PMA, which are analogous courses to those that are characteristic of clinical ALS. Contrary to our results, it has been described that PMA exhibits slower progression and longer survival duration compared with ALS.3 However, recent studies revealed that PMA follows a relentlessly progressive course and that the survival duration is not much longer than that of ALS.2 4 9 10 14 The relatively small number of patients in our study may have contributed to the absence of significant differences in the survival durations between the clinical PMA and ALS groups.

Our pathological results indicate that, of the patients with clinical PMA, 85% exhibited degeneration in the UMN and LMN systems, which corresponds with ALS. However, the remaining 15% of patients with clinical PMA lacked any apparent degeneration in the UMN system. A previous study reported that approximately 50% of all patients with PMA exhibit macrophages in the CST.5 Another report demonstrated the degeneration of the pyramidal tract and loss of Betz cells in 65% and 60%, respectively, of the patients diagnosed with the PMA phenotype.6 Our results revealed that patients with PMA more frequently had degeneration in the UMN system than those reported in previous studies; however, in a few patients with PMA, UMN degeneration remained undetectable at death. Our pathological results revealed differential UMN involvement between patients with PMA and indicated that PMA and ALS are continuous pathological entities. Regarding immunohistochemical aspects, several studies have revealed that TDP-43 pathology is commonly observed in the cerebral cortices or the subcortical grey matter of patients with PMA.7 8 In our results, TDP-43-positive neuronal or glial inclusions in the motor cortices or hippocampus were common in the clinical ALS and PMA groups and were found even in patients apparently lacking UMN degenerative changes. A recent report described the propagation of TDP-43 pathology in ALS, which starts from the UMN and LMN systems and spreads to the anteromedial temporal lobes through the motor neuron system.15 Based on this theory of TDP-43 propagation, TDP-43 pathology beyond the LMN system in patients with PMA may support the pathological continuity between these two clinical phenotypes.

The standard diagnostic criteria for ALS are the revised El Escorial criteria, which require a combination of UMN and LMN symptoms/signs for the diagnosis of ALS.12 However, it is often difficult to clinically determine whether the UMN is involved,16 which sometimes results in diagnostic difficulty. In our patient series, only 71.4% of the patients with clinical PMA were correctly diagnosed by the first referred physicians, although 94.6% of the patients with clinical ALS were diagnosed correctly. Recently, several studies have demonstrated the utility of radiological procedures, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, 1H MR spectroscopy and diffusion tensor imaging in the detection of UMN system deterioration in a subset of patients with PMA.14 17–20 Based on our results, a large subset of patients with PMA may have some degree of UMN degeneration. In such patients, these radiological or electrophysiological procedures would be expected to increase the sensitivity of detection of UMN degeneration. However, our results also indicate that some of the patients with PMA exhibit sparse morphological changes in the UMN system, even at death. It may be difficult to detect UMN degeneration using these procedures in such patients. To diagnose clinical patients with PMA displaying sparse UMN degeneration as ALS in the early phase of the disease course may be a future subject of focus.

A limitation of our study was the inability to evaluate the entire motor cortex and CST, and it is controversial whether patients with apparently intact UMN systems actually lack or have extremely mild UMN involvement. Another methodological limitation is that we evaluated axonal sizes and densities using neutral formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens. The tissues may be somewhat distorted when compared with conventional nerve fixation using glutaraldehyde followed by Epon embedding. Our methods were considered to be appropriate to assess the proportional changes in the sizes of pyramidal axons, but the absolute values of axonal diameters can vary from those that have been obtained using other histological techniques.13

In summary, 84.6% of patients with clinical PMA displayed UMN and LMN degeneration, which is consistent with the pathological profiles of ALS. In 15.4% of the patients with clinical PMA, degeneration in the UMN system was undetectable. The large axon density in the CST varied from low values to a normal range. In contrast, all of the clinical patients with ALS displayed a combination of UMN and LMN system degeneration and significantly reduced large axon density in the CST.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors specially thank Dr M Hasegawa, Department of Neuropathology and Cell Biology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, for performing the genetic analysis of the fused-in-sarcoma (FUS) genes.

Footnotes

Contributors: YR and NA contributed to the conception and design of the study. All of the authors participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. MY and GS drafted the manuscript. MI and HW assisted in writing and editing the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Research Committee of CNS Degenerative Diseases of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics committees of Nagoya University and Aichi Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006;314:130–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Carvalho M, Scotto M, Swash M, et al. Clinical patterns in progressive muscular atrophy (PMA): a prospective study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2007;8:296–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris FH. Adult progressive muscular atrophy and hereditary spinal muscular atrophies. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, De Jong JMBV, eds. Handbook of clinical neurology: diseases of the motor system. Vol 59 Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1991:13–34 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser J, van den Berg-Vos RM, Franssen H, et al. Disease course and prognostic factors of progressive muscular atrophy. Arch Neurol 2007;64:522–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ince PG, Evans J, Knopp M, et al. Corticospinal tract degeneration in the progressive muscular atrophy variant of ALS. Neurology 2003;60:1252–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownell B, Oppenheimer DR, Hughes JT. The central nervous system in motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1970;33:338–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geser F, Stein B, Partain M, et al. Motor neuron disease clinically limited to the lower motor neuron is a diffuse TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2011;121:509–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishihira Y, Tan CF, Hoshi Y, et al. Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis of long duration is associated with relatively mild TDP-43 pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2009;117:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim WK, Liu X, Sandner J, et al. Study of 962 patients indicates progressive muscular atrophy is a form of ALS. Neurology 2009;73:1686–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Berg-Vos RM, Visser M, Kalmijn S, et al. A long-term prospective study of the natural course of sporadic adult-onset lower motor neuron syndromes. Arch Neurol 2009;66: 751–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koike H, Hirayama M, Yamamoto M, et al. Age associated axonal features in HNPP with 17p11.2 deletion in Japan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:1109–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, et al. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2000;1:293–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobue G, Hashizume Y, Mitsuma T, et al. Size-dependent myelinated fiber loss in the corticospinal tract in Shy-Drager syndrome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 1987;37:529–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsumoto H, Ulug AM, Pullman SL, et al. Quantitative objective markers for upper and lower motor neuron dysfunction in ALS. Neurology 2007;68:1402–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Toledo JB, et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013;74:20–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swash M. Why are upper motor neuron signs difficult to elicit in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:659–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sach M, Winkler G, Glauche V, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI of early upper motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2004;127:340–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vucic S, Ziemann U, Eisen A, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiological insights. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:1161–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham JM, Papadakis N, Evans J, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging for the assessment of upper motor neuron integrity in ALS. Neurology 2004;63:2111–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prudlo J, Bißbort C, Glass A, et al. White matter pathology in ALS and lower motor neuron ALS variants: a diffusion tensor imaging study using tract-based spatial statistics. J Neurol 2012;259:1848–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.