Abstract

Objective

To examine sex-specific trends in 4-year mortality among young patients with first acute myocardial infarction (AMI), 1987–2006.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

We identified 37 276 cases (19.4% women; age, 25–54 years) from the Swedish Inpatient Register, 1987–2006, who had survived 28 days after an AMI.

Outcome measures

4-year mortality from all causes and standard mortality ratio (SMR).

Results

From the first to last 5-year period, the absolute excess risk decreased from 1.38 to 0.50 and 1.53 to 0.59 per 100 person-years among men aged 25–44 and 45–54 years, respectively. Corresponding figures for women were a decrease from 2.26 to 1.17 and from 1.93 to 1.45 per 100 person-years, respectively. Trends for women were non-linear, decreasing to the same extent as those for men until the third period, then increasing. For the last 5-year period, the standardised mortality ratio for young survivors of AMI compared with the general population was 4.34 (95% CI 3.04 to 5.87) and 2.43 (95% CI 2.12 to 2.76) for men aged 25–44 and 45–54 years, respectively, and 13.53 (95% CI 8.36 to 19.93) and 6.42 (95% CI 5.24 to 7.73) for women, respectively. Deaths not associated with cardiovascular causes increased from 21.5% to 44.6% in men and 41.5% to 65.9% in women.

Conclusions

Young male survivors of AMI have low absolute long-term mortality rates, but these rates remain twofold to fourfold that of the general population. After favourable development until 2001, women now have higher absolute mortality than men and a 6-fold to 14-fold risk of death compared with women in the general population.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Population-based study, that includes all cases with first acute myocardial infarction, aged 25–55 years, in Sweden during a period of 20 years.

Strengths include nationwide coverage and near-complete follow-up.

The main limitation is that the used register does not provide data covering clinical characteristics or treatment which could have been valuable to estimate their impact on mortality.

Introduction

Survival after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has improved during the past several decades in Sweden and elsewhere.1–3 Nonetheless, coronary heart disease (CHD) remains a major contributor to morbidity and mortality with more than one in five men and women currently dying from CHD in Europe.4 5 Survivors of AMI are known to have an impaired prognosis compared with the general population.6 In a recent study from England, the long-term risk of death due to any cause among survivors of first AMI was twice that of the general English population of equivalent age.7

Most patients with AMI are elderly; accordingly, most information on long-term survival is based on patients older than 55 years. However, about one in six AMI survivors is younger than 55 years.8 Knowledge of prognosis among young patients with AMI is essential because younger patients stand to lose more of their remaining life years compared with older patients. This applies particularly to women because women have a longer life expectancy.

Further, younger, but not older, women hospitalised with AMI have a worse long-term prognosis than men as shown in analyses of patient populations dating from the 1980s and 1990s.9 10 However, there have since been marked changes in treatment, diagnostic criteria and post-AMI prognosis. A recent study found that reductions in long-term mortality after 1985 were at least as high for women as for men with AMI,11 but the study did not specifically report findings for young patients. An additional study found that reductions in mortality were similar regardless of age but that younger patients are more likely to receive evidence-based care.12

Few data sets contain a sufficient number of young patients to reliably estimate risk of death compared with the general population. In addition, more information is needed about cause-specific mortality, because an unknown proportion of deaths may not be due to cardiovascular causes, and will thus be less amenable to coronary preventive measures. In the present study, we examined sex-specific trends in long-term survival in a register-based cohort of patients aged 25–54 years hospitalised with first AMI during 1987–2006, and compared death rates for men and women separately with those of the general population.

Methods

Registries and study population

Sweden has a publicly financed healthcare system, with some healthcare facilities privately run but still fully integrated into the healthcare system. The Swedish National Inpatient Register (IPR) has established complete national coverage since 1987. One study stated that positive predictive values (PPV) differ among diagnoses in the IPR, but are generally between 85 and95%. PPV for myocardial infarction was about 98–100% and the sensitivity was 77–91.5%.13 Another validation study concluded that the accuracy of correct diagnosis in AMI was 86% regardless (1987–1995) of age and gender.14 More recent data are lacking. Diagnoses in the IPR are coded according to the Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system (ICD 8th revision until 1986, 9th revision until 1996 and 10th revision thereafter). In the present study, data from the IPR and the Swedish Cause of Death Register were linked through personal identity numbers unique to each Swedish citizen. The Cause of Death Register is based on diagnosis from death certificates. In 2008, 0.8% of death certificates were missing or insufficient (2.7%).15 Validity of a correct diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) in the general population in 1995 was 87%.16

The present study included all 38 836 cases (31 216 men, 7620 women) in Sweden aged 25–54 years, discharged from hospital after first AMI in 1987–2006; AMI was defined as a principal discharge code according to the ICD-8 : 410 (until 1987), ICD-9: 410 (until 1996) and ICD-10: I21 (from 1997 onwards). After excluding 1560 cases who died during the first 28 days, 1169 men (3.01% of cases), median age 50, and 391 women (1.01% of cases), median age 49, 37 276 cases (7229 women and 30 047 men) with first AMI remained for analysis. Data from 1980 onwards were used to identify first AMIs only, with a time frame of 7 years throughout, to ensure that AMIs registered each year had the same chances of being identified as first AMIs. Owing to the 7-year time frame, 443 cases were recurrent AMIs after 7 years (53 women, median age 52; 390 men, median age 51). Criteria for diagnosis of AMI in Sweden have followed established guidelines, changing after the adoption of new AMI criteria in the year 2000.17 18 Thus, the characteristics of AMIs in our analysis changed during the study period. Use of troponins became standard after the year 2000.

Comorbidities were defined by the following main or contributory discharge codes during the preceding 7 years, including the index hospitalisation: diabetes (ICD-9 250; ICD-10 E10–E14), hypertension (ICD-9 401–405; ICD-10: I10–I15), valvular disease (ICD-9 394–397, 424; ICD-10 I05–I09, I34–I35), congenital heart disease (ICD-9 745–747; ICD-10 Q20–Q26), stroke (ICD-9 431–434, 436; ICD-10 I61–I64), chronic respiratory disease (ICD-9 490–496; ICD-10 J40–J47), malignancy (ICD-9 140–208; ICD-10 C00–C97), renal failure (ICD-9 584–586; ICD-10 N17–N19), coronary artery bypass grafting (3067, 3066, 3105, 3127, FNA, FNB, FNE, FNC) and percutaneous coronary intervention (3080, FNG 00, FNG 02, FNG 05).

Follow-up

We analysed 4-year all-cause mortality for four 5-year periods (1987–1991, 1992–1996, 1997–2001 and 2002–2006) through the Swedish Cause of Death Register. The following codes were used for assignment of causes of death among fatal cases: CVD (390–459, I00–I99), IHD (410–414, I20–I25), stroke (430–438, I60–I68) and all other causes (including malignancies; 140–208, C00–C97).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (R V.2.15.1 to obtain the graphs). For comorbidities, χ2 tests were used to evaluate differences between men and women and for trends; a p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. To compare mean age within the respective age groups, t tests were performed.

Standardised mortality ratios (SMR) with 95% CIs were calculated as the ratio of the observed to expected number of deaths, for 4-year follow-up during each period, estimated from rates in the general Swedish population by gender, age and calendar year, using life expectancy tables from Official Statistics of Sweden (SCB).

To examine the excess mortality risk in the study population absolute risk (AR) was calculated separately for the general population and the study population by dividing the observed mortality with person time. This yields an average annual excess risk for each period. The absolute excess risk (AER) is the difference between the observed and the expected AR. For standardisation purposes, the estimates were then multiplied by 100 person-years. The AER calculations add a useful measure of excess risk in absolute terms. Life expectancy tables from SCB) were used to calculate the expected mortality in the Swedish general population by gender, age and calendar year.

Cox proportional hazard regression, providing HR with 95% CIs, was used to estimate age and gender-specific changes in all-cause mortality over time.19 The first period (1987–1991) was used as reference. The multivariable models were adjusted for age, diabetes, hypertension, valvular and congenital heart disease, stroke, chronic respiratory disease, malignancy and renal failure. Furthermore, in the final model the periods were also tested for proportionality by interactions of age, time and with significant comorbidities only (men, 45–54; malignancies, women, 45–54; chronic respiratory disease).

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival probability. The proportionality assumption of Cox regression was tested by including interactions between covariates (age, gender and period) with time; neither interaction test was statistically significant.20 A log-rank test was conducted to study changes in survival between the time periods.

Results

Of the 37 276 cases in the study, 7905 (21.2%) were aged 25–44 years (19.6% women) and 29 371 (78.8%) were aged 44–54 years (19.3% women). Other than diabetes and hypertension (11% for both), this population had few diagnosed comorbidities (table 1). Women had more diabetes, hypertension, chronic lower respiratory disease and malignancies than men (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in 37 276 men and women aged <55 years with first AMI, 1987–2006

| All | Men | Women | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 37 276 | 30 047 | 7229 | |

| Age 25–44, n (%) | 7 905 (21.2) | 6 357 (21.2) | 1548 (21.4) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 40.21 (3.74) | 39.84 (4.04) | 0.055 | |

| Age 44–54, n (%) | 29 371 (78.8) | 23 690 (78.8) | 5681 (78.6) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 50.31 (2.75) | 50.39 (2.76) | 0.0549 | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 064 (10.9) | 3 017 (10.0) | 1047 (14.5) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 4110 (11.0) | 3141 (10.6) | 969 (13.4) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease, n (%) | 287 (0.77) | 211 (0.70) | 76 (1.05) | 0.0023 |

| Congenital heart disease | 36 (0.10) | 23 (0.08) | 13 (0.18) | 0.0111 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 412 (1.11) | 302 (1.01) | 110 (1.52) | 0.0002 |

| Chronic lower respiratory disease, n (%) | 557(1.49) | 368 (1.22) | 189 (2.61) | <0.0001 |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 354 (0.95) | 255 (0.85) | 99 (1.37) | <0.0001 |

| Renal failure | 230 (0.62) | 164 (0.55) | 66 (0.91) | 0.0003 |

| CABG*, n (%) | 253 (0.68) | 221 (0.74) | 32 (0.44) | 0.007 |

| PCI*, n (%) | 235 (0.63) | 198 (0.66) | 37 (0.51) | 0.16 |

*Procedures dating at least 6 months prior to hospitalisation for AMI.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Online supplementary table S1 shows the comorbidities for each 4-year period. All comorbidities except for congenital heart diseases increased significantly over time. Diabetes and hypertension were the most prevalent comorbidities in men and women but the rates of other comorbidities remained low even in the last period (<4%).

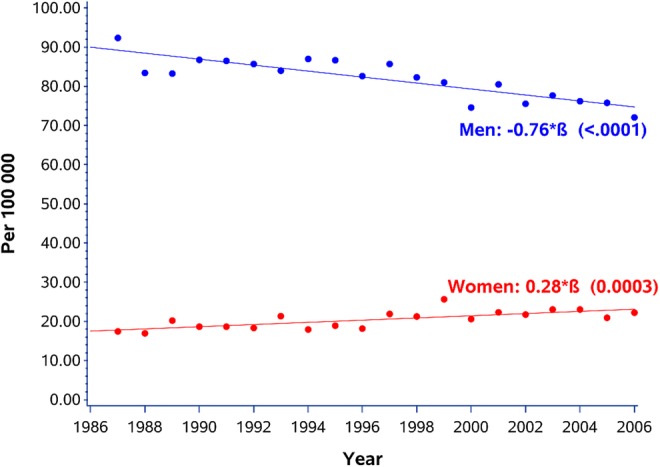

During the study period (1987–2006) annual rate per 100 000 population in men and women aged 25–54 years surviving a first AMI for at least 28 days decreased among men from 92.3 per 100 000 in 1987 to 72.1 in 2006 (figure 1). Women, on the other hand, showed a different pattern with an increase from 17.4 per 100 000 in 1987 to 22.3 in 2006 (p value for men <0.0001, for women 0.0003).

Figure 1.

Annual rate per 100 000 population in men and women aged 25–54 years surviving a first acute myocardial infarction for at least 28 days.

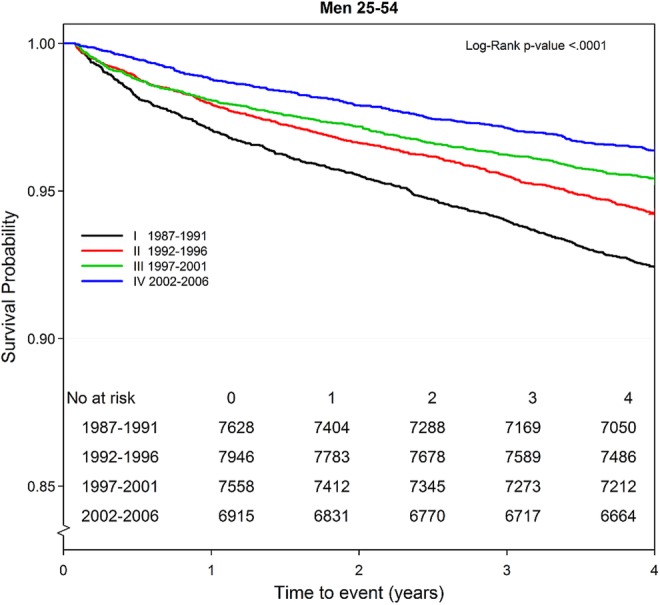

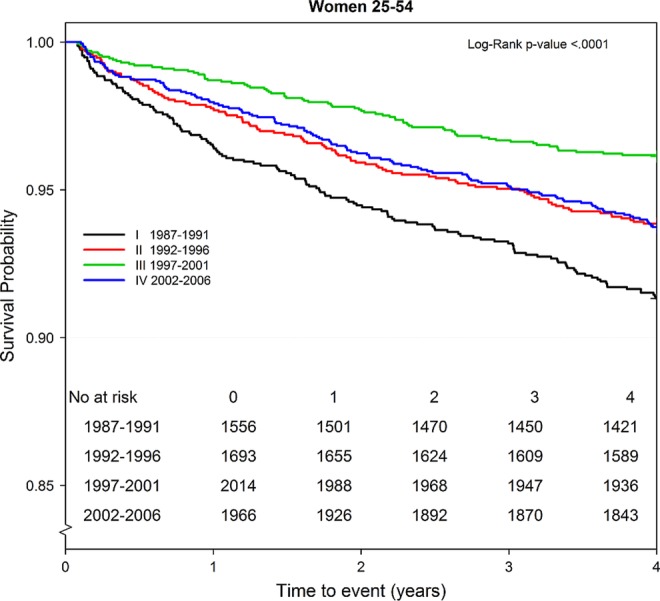

Survival in men improved continuously over the four 5-year periods (figure 2), while the prognosis in women improved until the third period (1997–2001), then reverted to a risk nearly identical to that in the second period (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Four-year trend in survival probability by period and time among men (n 30 047) aged 25–54 years with first acute myocardial infarction.

Figure 3.

Four-year trend in survival probability by period and time among women (n 7229) aged 25–54 years with first acute myocardial infarction.

Table 2 shows mortality by sex, age group and period. For men aged 25–44 years, the annual excess risk of dying decreased continuously from 1.38 to 0.50 deaths per 100 person-years from the first to last period, with an SMR of 4.34 (95% CI 3.04 to 5.87) during the last 5-year period. Corresponding figures for men aged 45–54 were a decrease from 1.53 to 0.59 with an SMR of 2.43 (95% CI 2.12 to 2.76) in the last period (2002–2006). Women displayed more complicated trends, starting from higher ARs of dying compared with men, decreasing sharply until a nadir in 1997–2001, and then increasing to 1.17 and 1.45 deaths per 100 person-years in women aged 25–44 and 45–54, respectively, in the last period. This was more than twice the risk in men of the corresponding age groups. Very high SMRs were noted, particularly for the youngest women, at 13.53 (95% CI 8.36 to 19.93) in the last period and 6.42 (5.24 to 7.73) in women aged 45–54 years.

Table 2.

Observed versus expected mortality ratio, estimated over 4 years, standardised mortality ratio, AR, absolute excess risk and HR for mortality by age group and period among 37276 men and women aged <55 years with first AMI

| Age, period | Observed* | Expected† | SMR (95% CI) | AR‡ | AER§ | HR (95% CI)¶ | HR (95% CI)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men 25–44 | |||||||

| 1987–1991 | 113 | 16 | 6.88 (5.67 to 8.20) | 1.61 | 1.38 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1992–1996 | 81 | 13 | 6.16 (4.89 to 7.57) | 1.25 | 1.05 | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.01) | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.98) |

| 1997–2001 | 58 | 10 | 5.70 (4.33 to 7.27) | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.82) | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.73) |

| 2002–2006 | 36 | 8 | 4.34 (3.04 to 5.87) | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.41 (0.28 to 0.60) | 0.30 (0.20 to 0.44) |

| Men 45–54 | |||||||

| 1987–1991 | 465 | 125 | 3.72 (3.39 to 4.07) | 2.10 | 1.53 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref)†† |

| 1992–1996 | 379 | 119 | 3.20 (2.88 to 3.53) | 1.56 | 1.07 | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.85) | 0.70 (0.61 to 0.81) |

| 1997–2001 | 289 | 108 | 2.69 (2.39 to 3.00) | 1.22 | 0.77 | 0.57 (0.49 to 0.66) | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.58) |

| 2002–2006 | 215 | 89 | 2.43 (2.12 to 2.76) | 0.99 | 0.59 | 0.47 (0.40 to 0.56) | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.39) |

| Women 25–44 | |||||||

| 1987–1991 | 34 | 2 | 17.55 (12.15 to 23.94) | 2.39 | 2.26 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| 1992–1996 | 28 | 2 | 17.99 (11.95 to 25.27) | 2.17 | 2.05 | 0.93 (0.56 to 1.55) | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.42) |

| 1997–2001 | 10 | 2 | 6.07 (2.89 to 10.42) | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.27 (0.13 to 0.55) | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.56) |

| 2002–2006 | 21 | 2 | 13.53 (8.36 to 19.93) | 1.26 | 1.17 | 0.55 (0.32 to 0.94) | 0.47 (0.27 to 0.83) |

| Women 45–54 | |||||||

| 1987–1991 | 101 | 15 | 6.90 (5.62 to 8.31) | 2.25 | 1.93 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref)‡‡ |

| 1992–1996 | 76 | 16 | 4.63 (3.65 to 5.73) | 1.45 | 1.14 | 0.64 (0.48 to 0.87) | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.76) |

| 1997–2001 | 68 | 19 | 3.58 (2.78 to 4.48) | 1.08 | 0.78 | 0.49 (0.36 to 0.66) | 0.44 (0.32 to 0.60) |

| 2002–2006 | 102 | 16 | 6.42 (5.24 to 7.73) | 1.72 | 1.45 | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.02) | 0.53 (0.39 to 0.71) |

*Observed number of deaths in the study population.

†Expected number of deaths in the general population.

‡AR per 100 person-years.

§Absolute excess risk per 100 person-years.

¶Age adjusted.

**Multiadjusted for age, diabetes, hypertension, valvular, congenital heart disease, stroke, chronical respiratory disease, malignancy and renal failure.

†Adjusted for changes and interaction over time, malignancy.

‡‡Chronic respiratory disease.

AER, absolute excess risk; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AR, absolute risk; SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

In men aged 25–44 years, the mortality risk decreased by 70% during the study period (multivariable adjusted HR: 0.30, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.44). A similar decrease was seen in men aged 45–54 years (multivariable adjusted HR: 0.32, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.38). Women aged 25–44 years had an overall decline in mortality risk of approximately 50% (multivariable adjusted HR: 0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.83). No significant decrease in mortality risk in the last, compared with the first period was observed in women aged 45–54 years (age-adjusted HR: 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.02), but after adjustment for comorbidities there was a significant decrease in risk (HR: 0.53, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.71).

Table 3 shows causes of death for the 2076 deaths that occurred within 4 years in this cohort. In 1987–1991, 74.8% of all deaths within 4 years were due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) (78.6% for men and 58.5% for women) with a majority due to IHD. However, during the last period (2002–2006), only 48.4% of all deaths were due to CVD (55.4% for men and, notably, only 34.1% for women).

Table 3.

Cause of death by period for 2076 deaths within 4 years among men and women aged <55 years with first AMI during 1987–2006

| Cause of death | Total n (%) | Men n (%) | Women n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987–1991 | 713 | 578 (81.1) | 135 (18.9) | |

| CVD | 533 (74.8) | 454 (78.6) | 79 (58.5) | <0.0001 |

| IHD | 481 (67.5) | 405 (70.1) | 76 (56.3) | 0.0021 |

| Stroke | 18 (2.52) | 16 (2.77) | 2 (1.48) | 0.3909 |

| All other causes | 180 (25.3) | 124 (21.5) | 56 (41.5) | <0.0001 |

| Malignancies | 55 (7.71) | 39 (6.75) | 16 (11.9) | 0.0454 |

| 1992–1996 | 564 | 460 (81.6) | 104 (18.4) | |

| CVD | 369 (65.4) | 318 (69.1) | 51 (49.0) | <0.0001 |

| IHD | 337 (59.8) | 295 (64.1) | 42 (40.4) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 6 (1.06) | 5 (1.09) | 1 (0.96) | 0.9104 |

| All other causes | 195 (34.6) | 142 (30.9) | 53 (51.0) | <0.0001 |

| Malignancies | 79 (14.01) | 57 (12.4) | 22 (21.2) | 0.0201 |

| 1997–2001 | 425 | 347 (81.7) | 78 (18.4) | |

| CVD | 242 (56.9) | 205 (59.1) | 37 (47.4) | 0.0606 |

| IHD | 216 (50.8) | 182 (52.5) | 34 (43.6) | 0.1573 |

| Stroke | 5 (1.18) | 3 (0.86) | 2 (2.56) | 0.2084 |

| All other causes | 183 (43.1) | 142 (40.9) | 41 (52.6) | 0.0606 |

| Malignancies | 63 (14.8) | 52 (15.0) | 11 (14.1) | 0.8428 |

| 2002–2006 | 374 | 251 (67.1) | 123 (32.9) | |

| CVD | 181 (48.4) | 139 (55.4) | 42 (34.1) | 0.0001 |

| IHD | 145 (38.8) | 116 (46.2) | 29 (23.6) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 12 (3.21) | 7 (2.79) | 5 (4.07) | 0.5106 |

| All other causes | 193 (51.6) | 112 (44.6) | 81 (65.9) | 0.00001 |

| Malignancies | 60 (16.0) | 28 (11.2) | 32 (26.0) | 0.0002 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

Discussion

The present study showed that young male survivors of AMI have low absolute long-term mortality rates; however, these rates remain are twofold to fourfold those of the general population. After favourable development in younger women until 2001, when new criteria for AMI were adopted and troponins became standard, women had higher absolute mortality than men in the last period and showed a dramatically higher risk of death than healthy women. However, fewer than half of all deaths in women were due to CVD in the last period.

Few studies have specifically investigated long-term outcomes in young patients with AMI. One Swedish study based on the Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA)21 investigated all consecutive patients younger than 46 years treated for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in Sweden, 1995–2006 (1748 men, 384 women). Long-term annual mortality was around 1% with no difference between men and women, similar to our study. Accordingly, in absolute terms and consistent with prior publications from our group,1 annual mortality rates in AMI survivors younger than 55 years are estimated at about 1%. This is in contrast to older patients in Sweden, among whom annual mortality rates are about 6% for those aged 65–74 years and more than 12% among patients aged 75–84 years.1 The current low absolute mortality figures are a vast improvement on prior estimates. In a retrospective analysis of 23 published studies from the prethrombolytic era, the annual death rate after the first year in patients with first AMI was 5% regardless of age or gender.22 In the late 1980s, the annual mortality for patients younger than 55 years was about 2%.1

There are several reasons for the observed decrease in mortality in younger patients with AMI. First, several pharmacological and coronary interventions were developed and implemented during the study period. Nauta et al12 showed that patients <55 years of age received evidence-based medical care and reperfusion to a greater extent than elderly patients. Second, some of the decrease is likely due to changes in diagnostic criteria during the study period, as well as more sensitive methods.17 23 This may imply that less severe AMIs are detected, with improved survival, but less specificity, as evidenced by increased comorbidities over time and a higher proportion of non-CVD deaths in the last period. Third, there have been changes in clinical presentation, with less severe infarctions,24 25 and fewer STEMIs.26 Factors that affect the risk of developing STEMI rather than non-STEMI include smoking26 and cardioprotective medications that lower the risk.27 Declining smoking rates and more medications used in primary prevention could thus have contributed to milder infarctions and better survival. Comorbidities increased during the study period. However, this can probably at least partly be due to improvements in clinical reporting due to financial incitements.13 The striking increase in hypertension can also probably be attributed to changes in criteria and guideline management by the WHO.28

There was a continuous decrease in case fatality among men; however, rates in women did not follow the same pattern. Mortality in women decreased until the third period and then increased during the fourth period to nearly the same level as in the second period. This may have been due to chance because the numbers were limited. However, it could also reflect differences in diagnostics. With increasing use of troponins, the rate of detection has increased, and this effect could be stronger for women than for men. In a study that simultaneously measured creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) and troponin,29 a 64% and 95% increase in the AMI rate among men and women, respectively, was observed when using troponins. Accordingly, the increasing mortality among women hospitalised in 2002–2006 could be due to the capture of other and more complicated types of myocardial damage because an increase in troponin levels is also seen in other conditions.30 Even so, comorbidities, although increasing over time, were still low in the most recent period. Since the most marked change between the third and the fourth period of our study was the change from CK-MB to troponins as the predominant marker for myocardial damage, we speculate that the additional AMIs captured by this more sensitive method are clinically different, not only in being smaller but also to an unknown extent reflecting myocardial damage not due to atherosclerotic disease. Circumstantial evidence for this might be derived from the increasing and much higher proportion of non-CVD deaths, as well as more comorbidities, in women compared with men over the study period. In the present study the results showed an increased rate of survivors but a decreasing trend in death in CVD among young women. These results strengthen the idea that increased all-cause mortality is most likely a result of a combination of the use of troponin and increasing comorbidities.

Few studies have compared mortality rates in young patients with AMI with those in the general population. A record linkage of hospital and mortality data identified 387 452 individuals in England, hospitalised with a main diagnosis of AMI in 2004–2010 and who survived at least 30 days.7 Long-term risk of death due to any cause among survivors of first AMI was twice that in the English general population of equivalent age, highest among younger patients aged 55–64 years (about twofold and threefold for men and women, respectively), and approached the mortality rate of the general population for those aged 85 years or more. Estimates for individuals younger than 55 years were not stated in the study by Smolina et al, but we have since been provided with information that mortality ratios were 2.6 for men and 5.6 for women aged 30–54 years after 4 years, which is more or less comparable to our findings (K Smolina, personal communication). For the period corresponding to that in the study by Smolina et al7 we found mortality ratios of 4.3 and 2.4 for men aged 25–44 and 45–54 years, respectively. For women aged 25–44 years, the estimated mortality ratio was 13.5, but this was based on very few cases (about four deaths per year). The estimate of 6.4 for women aged 45–54 years should be more reliable. It should be noted that women in the general population in this age range have very low mortality rates, which partially explains the high SMRs in women.

The main limitation of the present study is the reliance on administrative registers with no details of changes in several characteristics, such as biomarkers, ECG findings, smoking, medication, hyperlipidaemia, family history, ethnicity and socioeconomic status and a lack of other clinical information, notably hospital treatment and clinical presentation. Also, we were unable to apply uniform criteria for diagnosis over time. This limits considerably the interpretation that can be made; however, the findings should be applicable to current patients with AMI in an industrialised modern country. The quality of the data is obviously of fundamental importance, but validation studies of the IPR indicate reasonable accuracy.13 14 Incorrect death certificates could lead to uncertainty with respect to attributing cause of death,15 but IHD diagnoses has been estimated to be correct in 87% for ischaemic heart disease although the data for this study were collected two decades ago.16 The causes of death are also considered to be more reliable for the younger population than for the elderly population.15

The strengths of the study include nationwide coverage with virtually no loss to follow-up and the large sample size. Given the low mortality in absolute terms, larger populations are needed, particularly for women, because they constitute less than 20% of the AMI population younger than 55 years.

Conclusions

These data extend and update what is currently known about sex-specific absolute and relative survival in patients with AMI younger than 55 years, with a large population of more than 35 000 cases during a 20-year period. Among patients surviving for 28 days after AMI, the annual mortality rates are now comparatively low at approximately 1%. Given the much lower mortality in this age group in the general population, young survivors of AMI, particularly women, remain at a much higher risk of death, much of this, however, due to non-CVD causes. Accordingly, while mortality is low in absolute terms, younger women with AMI lose the survival advantage women normally have over men. Additional strategies to bring mortality closer to that which would be expected for this age group are needed, in particular for women.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SN, AR, LB, JB and KWG were involved in the study concept and design. SN, TZS, AR, LB, JB and KWG were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. SN, LB, JB, KWG, TZS, KF, SM and AR were involved in the drafting and revised the manuscript. All the authors involved in the critical revision of the final version of the manuscript. AR was the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number VR 521–2010-2984); the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (grant number 2012-0325); and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (grant number Epilife 2006-1506), the VGR region and the Swedish state under the ALF-LUA agreement.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: All personal identifiers were removed and replaced with a sequential number in the final data set. The protocol was approved by the regional Ethics Board of Gothenburg.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dudas K, Lappas G, Rosengren A. Long-term prognosis after hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction from 1987 to 2006. Int J Cardiol 2012;155:400–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langorgen J, Igland J, Vollset SE, et al. Short-term and long-term case fatality in 11 878 patients hospitalized with a first acute myocardial infarction, 1979–2001: the Western Norway cardiovascular registry. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16:621–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardoon SL, Whincup PH, Petersen I, et al. Trends in longer-term survival following an acute myocardial infarction and prescribing of evidenced-based medications in primary care in the UK from 1991: a longitudinal population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:770–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rayner M, Allender S, Scarborough P. Cardiovascular disease in Europe. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16(Suppl 2): S43–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols MTN, Scarborough P, Luengo-Fernandez R, et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2012. Brussels: European Heart Network; Sophia Antipolis: European Society of Cardiology, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagring AJ, Lappas G, Kjellgren KI, et al. Twenty-year trends in incidence and 1-year mortality in Swedish patients hospitalised with non-AMI chest pain. Data from 1987–2006 from the Swedish hospital and death registries. Heart 2010;96:1043–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, et al. Long-term survival and recurrence after acute myocardial infarction in England, 2004 to 2010. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:532–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale CP, Cattle B, Woolston A, et al. Resolving inequalities in care? Reduced mortality in the elderly after acute coronary syndromes. The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project 2003–2010. Eur Heart J 2012;33:630–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosengren A, Spetz CL, Koster M, et al. Sex differences in survival after myocardial infarction in Sweden; data from the Swedish National Acute Myocardial Infarction Register. Eur Heart J 2001;22:314–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Yarzebski J, et al. Sex differences in 2-year mortality after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:173–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nauta ST, Deckers JW, van Domburg RT, et al. Sex-related trends in mortality in hospitalized men and women after myocardial infarction between 1985 and 2008: equal benefit for women and men. Circulation 2012;126:2184–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nauta ST, Decker JW, Akkerhuis KM, et al. Age-dependent care and long-term (20 year) mortality of 14,434 myocardial infarction patients: changes from 1985 to 2008. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:693–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammar N, Alfredsson L, Rosen M, et al. A national record linkage to study acute myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(Suppl 1):S30–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Cause of death statistics—history, production methods and reliability. 2010. (In Swedish). http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-4-33 (accessed 16 Sep 2013).

- 16.Johansson LA, Björkenstam C, Westerling R. Unexplained differences between hospital and mortality data indicated mistakes in death certification: an investigation of 1,094 deaths in Sweden during 1995. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1202–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, et al. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 1994;90:583–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 1972;34:187–220 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawesson SS, Stenestrand U, Lagerqvist B, et al. Gender perspective on risk factors, coronary lesions and long-term outcome in young patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart 2010;96:453–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law MR, Watt HC, Wald NJ. The underlying risk of death after myocardial infarction in the absence of treatment. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2405–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh NI, Gona P, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in myocardial infarction incidence and case fatality in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart study. Circulation 2009;119:1203–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myerson M, Coady S, Taylor H, et al. Declining severity of myocardial infarction from 1987 to 2002: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation 2009;119:503–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goff DC, Jr, Howard G, Wang CH, et al. Trends in severity of hospitalized myocardial infarction: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study, 1987–1994. Am Heart J 2000;139:874–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjorck L, Rosengren A, Wallentin L, et al. Smoking in relation to ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: findings from the Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions. Heart 2009;95:1006–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjorck L, Wallentin L, Stenestrand U, et al. Medication in relation to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with a first myocardial infarction: Swedish Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA). Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1375–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization, International Society of Hypertension Writing Group. 2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens 2003;21:1983–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luepker RV, Duval S, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. The effect of changing diagnostic algorithms on acute myocardial infarction rates. Ann Epidemiol 2011;21:824–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier MA, Al-Badr WH, Cooper JV, et al. The new definition of myocardial infarction: diagnostic and prognostic implications in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1585–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.