Abstract

Objectives

Anaemia has an adverse impact on the outcome in the general patient population undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The aim of this study was to analyse the impact of anaemia on the 12-month clinical outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) undergoing PCI and therefore requiring intense antithrombotic treatment. We hypothesised that anaemia might be associated with a worse outcome and more bleeding in these anticoagulated patients.

Setting

Data were collected from 17 secondary care centres in Europe.

Participants

Consecutive patients with AF undergoing PCI were enrolled in the prospective, multicenter AFCAS (Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting) registry. Altogether, 929 patients participated in the study. Preprocedural haemoglobin concentration was available for 861 (92.7%; 30% women). The only exclusion criteria were inability or unwillingness to give informed consent. Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin concentration of <12 g/dL for women and <13 g/dL for men.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint was occurrence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) or bleeding events.

Results

258/861 (30%) patients had anaemia. Anaemic patients were older, more often had diabetes, higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, prior history of heart failure, chronic renal impairment and acute coronary syndrome. Anaemic patients had more MACCE than non-anaemic (29.1% vs 19.4%, respectively, p=0.002), and minor bleeding events (7.0% vs 3.3%, respectively, p=0.028), with a trend towards more total bleeding events (25.2% vs 21.7%, respectively, p=0.059). No difference was observed in antithrombotic regimens at discharge. In multivariate analysis, anaemia was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality at 12-month follow-up (hazard ratio 1.62, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.51, p=0.029).

Conclusions

Anaemia was a frequent finding in patients with AF referred for PCI. Anaemic patients had a higher all-cause mortality, more thrombotic events and minor bleeding events. Anaemia seems to be an identification of patients at risk for cardiovascular events and death.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00596570.

Keywords: HAEMATOLOGY, CARDIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The enrolment of consecutive patients with the only exclusion criteria being unwillingness/inability to participate in the study. In this sense, the study population represents well real-world patients with AF referred for PCI.

The study adds to our knowledge on the prevalence and impact of anaemia in patients with AF undergoing PCI and thus requiring combination antithrombotic medication. It shows that anaemia is a frequent finding and that even mild anaemia has an adverse impact on outcome.

The current study has the inherent limitations of the observational study design, including individual risk-based decision-making in treatment choices, which may introduce selection bias. Another possible confounder is the heterogeneity of the AF population among the participating centres and some differences in the periprocedural routines.

The aetiology of anaemia could not be systematically investigated and is therefore outside the scope of this study.

Introduction

It is estimated that around 5% of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) need long-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) due to atrial fibrillation (AF).1 2 Yet, the current recommendations on the management of antithrombotic treatment in patients with AF undergoing PCI and stenting are mainly derived from small studies, amounting to a weak level of evidence.3 4 Moreover, the real-world management of patients on OAC undergoing PCI is variable, and only partially adherent to the current recommendations.5

Defined according to the WHO, anaemia has been reported to affect nearly 25% of patients undergoing PCI and stenting. Anaemic patients undergoing PCI are generally older, with more comorbidities, and have higher rates of in-hospital mortality and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), as well as 1-year mortality.6 7 Furthermore, low admission haemoglobin level was found to be an independent predictor of in-hospital and long-term mortality, and was associated with higher rates of in-hospital minor and major bleeding events in patients undergoing primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (MI).8 9

However, little is known about the effect of anaemia on the outcome of patients with AF undergoing PCI, and thus requiring intensive antithrombotic treatment. Anaemia is possibly a marker of high bleeding risk, which could be aggravated by the underlying cause. Therefore, we analysed data from the prospective AFCAS (Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting) registry to explore the impact of anaemia on the 12-month clinical outcome of patients with AF undergoing PCI.10

Methods

Patients

The AFCAS registry (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00596570) is a prospective, multicenter registry that enrolled patients with AF referred for PCI in five European countries. The study design has been described in detail previously.11 Patients were enrolled if they had: (1) history of AF (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent) or (2) ongoing AF during the index PCI. Of the 929 participants, 861 (92.7%) had a preprocedural haemoglobin count available and were included in this analysis.

Coronary angiography and PCI were performed via either radial or femoral access, and haemostasis was achieved according to local practice. Coronary lesions were treated according to contemporary interventional techniques. Low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin sodium, dalteparin), unfractionated heparin, bivalirudin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were administered at the operator's discretion. The postdischarge medication was completely at the discretion of the treating physician.

The primary endpoints of the current study were (1) occurrence of MACCE defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, any non-fatal MI, any revascularisation, definite/probable stent thrombosis, transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or stroke and peripheral arterial embolism; (2) bleeding events and (3) total adverse events (a composite of MACCE plus bleeding events). Bleeding events were defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria as minor (BARC 2) and major (BARC 3a, 3b, 3c and 5) bleeding events; however, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)-related bleeding was excluded12 (see online table S1).

Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin concentration of <12 g/dL for women and <13 g/dL for men, according to the definition of the WHO.13 Chronic renal impairment was defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min.

Ethical aspects

The study was initiated by the investigators and conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2002. Informed written consent was obtained from every patient after full explanation of the study protocol. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participating centres.

Statistical analysis

For analysis, patients with available preprocedural measurement of haemoglobin concentration were divided into two subgroups: anaemic patients and control patients without anaemia. Continuous variables were reported as the mean±SD if normally distributed and as median (IQR) if they were skewed. Data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Categorical variables were described with absolute and relative (percentage) frequencies. Comparisons between the two study subgroups were performed using the unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. The Cox regression hazard model was used to identify the independent predictors of MACCE and all-cause mortality at 12-month follow-up. Baseline variables correlating at p<0.10 level with the dependent variable in univariate analyses were entered in the Cox regression model as covariates. The Cox regression hazard model was used to identify the independent predictors of MACCE and all-cause mortality at 12-month follow-up in the subgroup of anaemic patients. Finally, we constructed Kaplan-Meier survival curves to display the time-to-event relationship for the occurrence of all-cause mortality, MACCE and all bleeding events. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS V. 16.0.1, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 929 patients enrolled in the AFCAS registry and followed up for 12 months, 861 (92.7%) had available preprocedural measurement of haemoglobin concentration, of whom 258 (30%) had anaemia and 603 (70%) had normal haemoglobin concentration. Anaemic patients were older; more likely to have diabetes mellitus, hypertension, history of heart failure and chronic renal impairment; HAS-BLED score ≥3; higher CHA2DS2-VASc score and more likely presented with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) as opposed to chronic stable angina, compared with those without anaemia (p<0.05 for all), as shown in table 1. Furthermore, anaemic patients had more vessels treated during the index procedure and a greater total stent length, compared with those without anaemia (p<0.05 for both; table 2). At discharge, no significant differences were seen in the prescription of antithrombotic medications in the two study groups (p=0.15; table 3). The duration of clopidogrel treatment did not differ in anaemic versus non-anaemic patients on triple therapy (median (IQR): 3 (11) vs 3 (5) months, p=0.61), on dual antiplatelet therapy (median (IQR): 12 (11) vs 12 (11) months, p=0.72) or on vitamin K antagonist+clopidogrel (median (IQR): 12 (11) vs 3 (11) months, p=0.65). Proton pump inhibitors were more frequently prescribed to patients with anaemia versus those without (47.7 vs 31.3%, respectively, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the two study subgroups

| Variable | Anaemia (N=258) | Non-anaemic (N=603) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 76 [9] | 73 [11] | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 89 (34.5) | 170 (28.2) | 0.074 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 119 (46.1) | 191 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 162 (62.8) | 407 (67.5) | 0.183 |

| Current or ex-smoking | 26 (10.1) | 62 (10.3) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension | 221 (85.7) | 503 (83.4) | 0.48 |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 103 (39.9) | 229 (38.0) | 0.594 |

| Persistent atrial fibrillation | 22 (8.5) | 78 (12.9) | 0.081 |

| Permanent atrial fibrillation | 129 (50) | 294 (48.8) | 0.766 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score >4 | 148 (57.4) | 235 (39.0) | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED score ≥3 | 215 (83.3) | 441 (73.1) | 0.001 |

| History of peptic ulcer | 17 (6.6) | 27 (4.5) | 0.236 |

| History of cerebral haemorrhage | 4 (1.6) | 6 (1.0) | 0.497 |

| History of GI haemorrhage | 9 (3.5) | 12 (2.0) | 0.144 |

| History of heart failure | 69 (26.7) | 113 (18.7) | 0.011 |

| eGFR below 60 mL/min | 119 (52.2) | 175 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Prior transient ischaemic attacks | 12 (4.7) | 30 (5.0) | 1.00 |

| Prior stroke | 36 (14.0) | 67 (11.1) | 0.252 |

| Prior MI | 76 (29.5) | 146 (24.2) | 0.126 |

| Prior PCI | 47 (18.2) | 100 (16.6) | 0.555 |

| Prior coronary bypass surgery | 47 (18.2) | 78 (12.9) | 0.057 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 123 (47.7) | 189 (31.3) | <0.001 |

| Stable angina pectoris | 81 (31.4) | 289 (48.0) | <0.001 |

| ACS | 177 (68.6) | 313 (52.0) | <0.001 |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 53 (20.5) | 107 (17.7) | 0.34 |

| Non-ST-elevation MI | 83 (32.2) | 132 (21.9) | 0.002 |

| ST-elevation MI | 41 (15.9) | 74 (12.3) | 0.156 |

Continuous variables are presented as median [IQR], whereas categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage).

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GI, gastrointestinal; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2.

Procedural data of the two study subgroups

| Variable | Anaemia (N=258) | Non-anaemic (N=603) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral access | 196 (76.0) | 435 (72.1) | 0.275 |

| Number of treated vessels | 1.22±0.45 | 1.15±0.41 | 0.04 |

| DES | 67 (27.0) | 138 (23.6) | 0.293 |

| Periprocedural INR | 1.9 [1] | 1.88 [1] | 0.509 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | 3 [1] | 3 [1] | 0.965 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 20 [18] | 19 [14] | 0.014 |

| Procedural success | 252 (97.7) | 582 (96.5) | 0.085 |

| Haemostasis | |||

| Manual compression | 112 (43.4) | 249 (41.3) | 0.765 |

| Compression device* | 49 (19.0) | 155 (25.7) | 0.083 |

| Access-site closure device† | 82 (31.8) | 165 (27.4) | 0.154 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median [IQR], whereas categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage).

*FemoStop, pneumatic compression device (Radi medical system, Sweden).

†Angioseal, closure device (St Jude medical, USA).

DES, drug-eluting stents; INR, International Normalised Ratio.

Table 3.

Prescription of antithrombotic medications at discharge in the two study subgroups

| Variable | Anaemia (N=258) | Non-anaemic (N=603) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triple therapy | 181 (70.2) | 442 (73.3) | 0.15 |

| DAPT | 58 (22.5) | 100 (16.6) | |

| VKA plus clopidogrel | 15 (5.8) | 51 (8.5) | |

| VKA plus aspirin | 4 (1.6) | 10 (1.7) |

Variables are presented as frequency (percentage).

DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

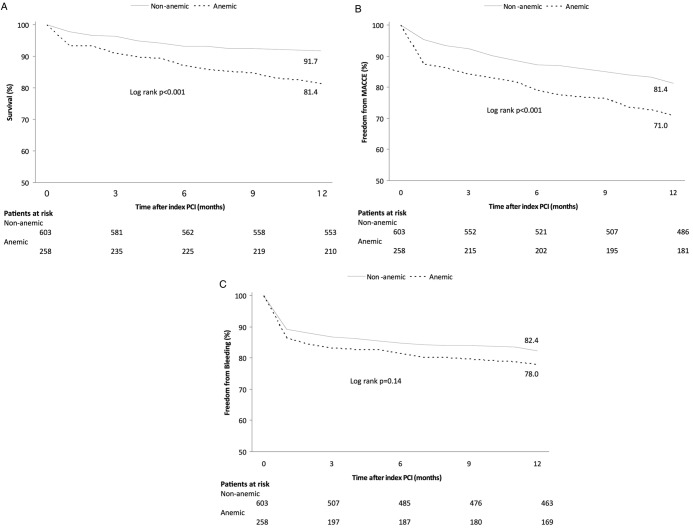

Clinical outcome

Clinical outcomes at 12-month follow-up are presented in table 4 and figure 1. The primary endpoint of MACCE was significantly more frequent in anaemic patients than those without anaemia (29.1 vs 19.4%, respectively, p=0.002). This difference was driven by higher rates of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI and definite/probable ST (p<0.05 for all). Anaemic patients had more BARC 3a bleeding events (7.0% vs 3.3%, respectively, p=0.028). No difference was seen in BARC 5 bleedings. There was a trend towards more total bleeding events (25.2% in anaemic vs 21.7% in controls, p=0.059; for detailed information on bleeding events see see online table S2). Total adverse events occurred more frequently in anaemic versus non-anaemic patients (43% vs 31.5%, respectively, p=0.001).

Table 4.

Clinical outcome at 12-month follow-up in the two study subgroups

| Endpoints | Anaemia (N=258) | Non-anaemic (N=603) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE | 75 (29.1) | 117 (19.4) | 0.002 |

| All-cause mortality | 48 (18.6) | 50 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Stroke/TIA | 6 (2.3) | 17 (2.8) | 0.819 |

| Peripheral arterial embolism | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction | 24 (9.3) | 27 (4.5) | 0.011 |

| Any revascularisation | 19 (7.4) | 51 (8.5) | 0.683 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosis | 10 (3.9) | 4 (0.7) | 0.002 |

| Total bleeding events | 65 (25.2) | 131 (21.7) | 0.059 |

| Minor bleeding (BARC 2) | 22 (8.5) | 48 (8.0) | 0.786 |

| Major bleeding (BARC 3a, 3b, 3c, 5) | 33 (12.8) | 56 (9.3) | 0.142 |

| Access site complications | 25 (9.7) | 49 (8.1) | 0.51 |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 7 (2.7) | 18 (3.0) | 1.0 |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 10 (3.9) | 5 (0.9) | 0.002 |

| Need for corrective surgery | 5 (1.9) | 8 (1.3) | 0.25 |

| Prolonged hospitalisation | 15 (5.8) | 23 (3.8) | 0.21 |

| Total adverse events | 111 (43.0) | 190 (31.5) | 0.001 |

Variables are presented as frequency (percentage).

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; TIA, transient ischaemic attacks.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the occurrence of adverse events in anaemic (dotted lines) versus non-anaemic (solid line) patients at 2-month follow-up: all-cause mortality (A), MACCE free survival (B) and bleeding event-free survival (C). MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The incidence of definite/probable stent thrombosis was significantly higher in anaemic versus non-anaemic patients (3.9% vs 0.7%, respectively, p=0.002). Patients who developed stent thrombosis more often presented with ACS than those who did not (80.0% vs 56.6%, respectively, p=0.07); however, the use of triple therapy did not differ statistically between groups (60.0% vs 73.3%, respectively, p=0.25). Overall, nearly half (46.7%) of ST events occurred early (<30 days). Acute (<24 h after index PCI), early (<30 days) and late ST (>30 and <365 days) were detected in 1 (0.4%) vs 1 (0.2%; p=0.51); 4 (1.6%) vs 2 (0.3%; p=0.07) and 6 (2.3%) vs 2 (0.3%; p=0.01) in patients with anaemia versus those without anaemia, respectively.

In univariate analysis, age above 75, diabetes, congestive heart failure, anaemia, chronic renal impairment, ACS at presentation and total stent length were strongly correlated with MACCE and all-cause mortality at 12-month follow-up. In the Cox regression model, including all the above variables, independent predictors of all-cause mortality were anaemia (hazard ratio (HR) 1.62, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.51, p=0.029), ACS at presentation (HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.37 to 3.75, p=0.001), chronic renal impairment (HR 2.35, 95% CI 1.52 to 3.65, p<0.001) and diabetes (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.70, p=0.009). In contrast, anaemia as a categorical variable was not an independent predictor of MACCE at 12-month follow-up, unlike age above 75 years (HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.4, p=0.004), diabetes (HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.3, p=0.002), ACS at presentation (HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.3, p=0.003) and congestive heart failure (HR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.1, p=0.03).

We performed the multivariate model also using haemoglobin as a continuous variable. Independent predictors of all-cause mortality were preprocedural haemoglobin (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.93, p=0.002), ACS at presentation (HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.45, p=0.005), chronic renal impairment (HR 2.06, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.24, p=0.002) and diabetes (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.70, p=0.01) in a Cox regression model including age over 75 years, total stent length and number of treated vessels as covariates. On the contrary to what was found when assessing anaemia as a categorical variable, haemoglobin as a continuous variable also predicted MACCE. Independent predictors of MACCE were preprocedural haemoglobin (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.98, p=0.016), ACS at presentation (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.18, p=0.012), congestive heart failure (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.04, p=0.035), age over 75 years (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.45, p=0.001) and diabetes (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.13, p=0.007) in a Cox regression model including also total stent length, chronic renal impairment and number of treated vessels as covariates.

When the anaemic patients were analysed separately in the Cox regression model, age over 75 years and ACS at presentation were identified as independent predictors of MACCE at 12 months, and chronic renal impairment, age over 75 years and ACS at presentation as independent predictors of all-cause mortality.

Among 861 patients with available preprocedural measurement of haemoglobin concentration, 26 (2.8%) had severe anaemia (defined as haemoglobin below 10 g/dL). In this subgroup, MACCE occurred in 12 (46.2%) patients, 10 (38.5%) patients died and 8 (30.8%) experienced a BARC 2–5 bleeding episode. At discharge, triple therapy was prescribed in 18 (69.2%) patients, dual antiplatelet therapy in 8 (30.8%) and no patient was prescribed vitamin K antagonists plus a single antiplatelet drug. Proton pump inhibitors were prescribed at discharge in 18 (69.2%) patients, and 1 (3.8%) patient had a history of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Discussion

Our study is the first report on the impact of anaemia on the long-term clinical outcome of patients with AF undergoing PCI. The AFCAS registry represents a real-life cohort of high-risk patients with AF requiring PCI. The results of the current study showing that 30% of the patients were anaemic confirm the previous reports that anaemia is a frequent finding in real-world patients with AF referred for PCI.6–9 14 Anaemic patients in the AFCAS registry were older, with more comorbidities and presented more often with ACS, compared with non-anaemic patients, as also reported in previous cohorts.6 7 9 14

Overall, the 12-month clinical outcome was worse in anaemic patients. Anemia remained an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in multivariate analysis. The higher rate of all-cause mortality might be related to the higher risk profile in anaemic patients, as well as the underlying disease causing anaemia. Furthermore, anaemic patients had more frequent MACCE at 12 months, primarily driven by higher rates of all-cause mortality, and non-fatal MI. However, anaemia was not an independent predictor of MACCE. The higher rate of non-fatal MI might be explained, at least in part, by the higher frequency of ACS at presentation in anaemic patients.

The estimated thromboembolic risk of anaemic patients according to CHADS2 score was higher. However, no excess in TIA or stroke was seen during the follow-up and only a trend towards more bleeding was observed. This is contradictory to previous studies which have reported a higher incidence of cardiac and cerebrovascular thrombotic events at long-term follow-up in anaemic versus non-anaemic patients in various patient cohorts referred for PCI.7 9 14–18 The relatively small number of complications in our patient cohort might explain this difference.

The estimated bleeding risk according to the HAS-BLED score was higher in anaemic patients, but there was only a trend towards increased risk of major bleeding. However, the results of the current study support the previous reports on the increased bleeding risk associated with anaemia in various patient groups undergoing PCI.8 9 19 Anaemia may be a marker and consequence of an underlying condition such as bleeding diathesis, occult gastrointestinal bleeding or malignancy that augments the bleeding risk. An interesting observation is that neither the presence of anaemia nor higher estimated bleeding risk seemed to affect the clinician's choice of antithrombotic medications at discharge. In view of our results, patients with anaemia tolerated triple therapy surprisingly well with only a trend towards increased bleeding.

We observed that the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis was significantly higher in anaemic versus non-anaemic patients (p=0.002). ACS at presentation may have contributed to the higher rate of stent thrombosis in anaemic patients, as patients with anaemia more often presented with ACS versus those without anaemia. In addition, in individual cases, the presence of anaemia may have influenced the choice of antithrombotic medication. Also, a bleeding event could have led to interruption of combination antithrombotic therapy, and thus to a higher risk of stent thrombosis. Consistent with our results, Pilgrim et al14 observed a higher rate of definite stent thrombosis at 4-year follow-up in anaemic patients who underwent PCI with unrestricted use of drug-eluting stents, compared with non-anaemic ones. Interestingly, in a recent study, anaemia was the only independent predictor of high residual platelet reactivity on clopidogrel in a series of patients undergoing PCI.20 These observations warrant further studies to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

The effect of anaemia on the clinical outcome of PCI appears early during hospitalisation. Kaplan-Meier event-free survival curves in the current study revealed that most of the thrombotic as well as bleeding events occurred early (within 30 days) following the index PCI (figure 1). This finding is in line with previous reports.6 8 9 15 In patients with coronary artery disease, anaemia may aggravate myocardial ischaemia and unveil significant coronary obstruction. Cardiac output increases in patients with anaemia in order to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the tissues. This increases heart rate and induces myocardial hypertrophy, which in turn increases myocardial oxygen demand, and further exaggerates the myocardial oxygen demand/supply imbalance.21 On the other hand, patients with severe anaemia receive more frequent blood transfusion, which was reported to have an adverse impact on survival after PCI.22 Unfortunately, information on blood transfusions was not available in our registry except for the in-hospital phase. More importantly, anaemia is frequently associated with severe underlying chronic diseases which may compromise long-term survival. Of note is a recent report suggesting that in patients who underwent PCI with drug-eluting stents, those in whom anaemia improved at follow-up had less MACCE at a median follow-up of 25 months, compared with those with sustained anaemia, suggesting that a transient cause is less detrimental than a long-standing state causing anaemia, for example, malignancy.16

Limitations of the study

The current study has the inherent limitations of the observational study design, including individual risk-based decision-making in treatment choices, which may introduce selection bias, even though we did not observe any difference between the two study groups in the antithrombotic treatment prescribed at discharge. Another possible confounder is the heterogeneity of the AF population among the participating centres and some differences in the periprocedural routines. Moreover, the aetiology of anaemia was not systematically investigated; yet, it is beyond the scope of the current study. The strength of the study is the enrolment of consecutive patients with the only exclusion criteria being unwillingness/inability to participate in the study. In this sense, the study population represents well real-world patients with AF referred for PCI.

Conclusion

Anaemia was a frequent finding in patients with AF referred for PCI. Anaemia seems to be an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality during 12-month follow-up. Anaemia is also associated with more MACCE and a trend towards a higher rate of bleeding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study coordinator Tuija Vasankari, RN, for her valuable input in data management.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP and TK participated in data collection and analysis and writing the manuscript. WN contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript. AS, AR, KN, PK and PK contributed to data collection and critical revision of the manuscript. GYHL contributed to study design, data collection and critical revision of the manuscript. JKEA acted as the primary investigator of the AFCAS study and contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Helsinki, Finland.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The ethical committees of the participating hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The whole study data is available from the study coordinator Ms Tuija Vasankari email: tuija.vasankari@tyks.fi or TK tuomas.kiviniemi@utu.fi in addition to corresponding author JKEA juhani.airaksinen@tyks.fi.

References

- 1.Rubboli A, Halperin JL, Airaksinen KE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients treated with oral anticoagulation undergoing coronary artery stenting. An expert consensus document with focus on atrial fibrillation. Ann Med 2008;40:428–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubboli A, Colletta M, Valencia J, et al. for the WARfarin, Coronary STENTing (WAR-STENT) Study Group. Periprocedural management and in-hospital outcome of patients with indication for oral anticoagulation undergoing coronary artery stenting. J Interv Cardiol 2009;22:390–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lip GYH, Huber K, Andreotti F, et al. Antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing coronary stenting: executive summary—a Consensus Document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 2010;31:1311–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faxon DP, Eikelboom JW, Berger PB, et al. Consensus document: antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary stenting. A North-American perspective. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:522–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubboli A, Dewilde W, Huber K, et al. The management of patients on oral anticoagulation undergoing coronary stent implantation: a survey among interventional cardiologists from eight European countries. J Interv Cardiol 2012;25:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKechnie RS, Smith D, Montoye C, et al. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2). Prognostic implication of anemia on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2004;110:271–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Aymong ED, et al. Impact of anemia on outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:1023–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dündar C, Oduncu V, Erkol A, et al. In-hospital prognostic value of hemoglobin levels on admission in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty. Clin Res Cardiol 2012;101:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayhan E, Aycicek F, Uyarel H, et al. Patients with anemia on admission who have undergone primary angioplasty for ST elevation myocardial infarction: in-hospital and long-term clinical outcomes. Coron Artery Dis 2011;22:375–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiviniemi T, Karjalainen P, Rubboli A, et al. Thrombocytopenia in patients with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2013;112: 493–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlitt A, Rubboli A, Lip GY, et al. for the AFCAS (Management of patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting Study Group). The management of patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation: in-hospital-data from the atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary artery stenting study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013;82:E864–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation 2011;123:2736–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.[No authors listed] Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO scientific group World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1968;405:5–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilgrim T, Vetterli F, Kalesan B, et al. The impact of anemia on long-term clinical outcome in patients undergoing revascularization with the unrestricted use of drug-eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:202–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PC, Kini AS, Ahsan C, et al. Anemia is an independent predictor of mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:541–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TH, Koh YS, Chang K, et al. CathOlic university of Korea—percutAneous Coronary inTervention registry investigators. Improved anemia is associated with favorable long-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing PCI. Coron Artery Dis 2012;23:391–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitai Y, Ozasa N, Morimoto T, et al. on behalf of the CREDO-Kyoto registry investigators. Prognostic implications of anemia with or without chronic kidney disease in patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 2013;168: 5221–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosseini SK, Ansari MJ, Lotfi Tokaldany M, et al. Association between preprocedural hemoglobin level and 1-year outcome of elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiovasc Med 2014;15:331–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manzano-Fernández S, Pastor FJ, Marín F, et al. Increased major bleeding complications related to triple antithrombotic therapy usage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary artery stenting. Chest 2008;134:559–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toma C, Zahr F, Moguilanski D, et al. Impact of anemia on platelet response to clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1148–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Hamett JD, et al. The impact of anemia on cardiomyopathy, morbidity, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;28:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maluenda G, Lemesle G, Ben-Dor I, et al. Value of blood transfusion in patients with a blood hematocrit of 24% to 30% after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1069–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.