Abstract

Scientific and clinical activities undertaken by public health agencies may be misconstrued as medical research.

Most discussions of regulatory and legal oversight of medical research focus on activities involving either patients in clinical practice or volunteers in clinical trials. These discussions often exclude similar activities that constitute or support core functions of public health practice. As a result, public health agencies and practitioners may be held to inappropriate regulatory standards regarding research.

Through the lens of the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, and using several case studies from these departments, we offer a framework for the adjudication of activities common to research and public health practice that could assist public health practitioners, research oversight authorities, and scientific journals in determining whether such activities require regulatory review and approval as research.

Title 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 46, the federal policy for the protection of human participants that is informally known as the “Common Rule,” defines research as “a systematic investigation … designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.”1 This definition was developed to protect human research participants, to promote voluntary informed consent, and to require scientific and ethical review and oversight of research through independent institutional review boards (IRBs). However, attempts to differentiate research from public health practice —defined herein as all nonresearch public health activities—through the rubrics of the Common Rule are problematic in light of their overlapping spheres (see the box on page 597). For instance, Snider and Stroup have observed that “systematic investigations” producing “generalizable knowledge” can describe legally mandated, ethical public health activities—such as surveillance, emergency response, and program evaluation—as well as human participant research.2

Elements Common to Public Health Practice and Public Health Research

| • Use systematic methods. |

| • Based on scientific evidence. |

| • Might use epidemiological study design. |

| • Might involve selection of participants. |

| • Might involve the collection and assessment of personally identifiable and protected health information. |

| • Might involve statistical analysis of data. |

| • Might result in publication of findings in peer-reviewed literature. |

| • Might contribute to generalizable knowledge. |

| • Might involve hypothesis testing. |

Public health practice frequently employs case–control, cohort, and cross-sectional study designs, as well as other systematic methodologies that are used in research. Likewise, findings from public health activities, such as a disease outbreak investigation, may lead to generalizable knowledge even though the investigation was not designed to develop such knowledge. Publication of such generalizable knowledge in peer-reviewed literature presents challenges to public health practitioners and journal editors, because of journals’ policies that may require that such work be subjected to IRB review prior to submission.

DEFINING PUBLIC HEALTH PRACTICE

For practical and ethical reasons, clearly distinguishing between research performed by public health practitioners and agencies (e.g., public health research) and public health practice is critical. As other authors have advocated, the major distinction should reside in the a priori purpose for which the activity was designed.2–5 The purpose of research is to generate or contribute to generalizable knowledge. The purpose of public health practice is to prevent disease or injury and to improve the health of communities through such activities as disease surveillance, program evaluation, and outbreak investigation. Devices such as decision trees may assist public health agencies and practitioners in making valid, defensible, and reproducible decisions regarding whether proposed work should be classified as research or public health practice. Here, we chronicle key initiatives to differentiate public health practice from research, discuss the challenges of such differentiation through several case studies, and present an algorithm intended to help public health practitioners, researchers, IRBs, journal editors, and others to distinguish between public health practice and research.

KEY INITIATIVES

The challenge of distinguishing public health practice from research is not new, as evidenced by a number of key initiatives to provide guidance. The Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) makes the distinction between public health practice and research by defining the proposed work’s purpose and beneficiaries. Whereas public health research is designed to generate knowledge that primarily benefits those beyond the participating community, public health practice is intended to benefit those within the participating community. The essential characteristics of public health practice include

specific legal authorization for conducting the activity,

governmental duty to perform the activity to protect the public’s health,

direct performance or oversight of the activity by a governmental public health authority (or authorized partner) accountable to the public,

legitimacy of involving nonvolunteers, and

activities supported by ethical principles that focus on populations while respecting the dignity and rights of individuals.3

The CSTE report also identifies attributes considered by the authors to be less relevant for making this distinction, such as who is performing or funding the work, which methods are employed for collecting and analyzing data, and whether and where the findings will be published. However, from a regulatory perspective, who is performing or funding the work does have relevance. The current regulations apply only to research conducted or supported by the Common Rule signatories, including over a dozen federal agencies.

Besides CSTE guidance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2010 policy outlines distinctions between public health practice and research.4 The associate director for science in each center, designated as the official responsible for drawing this distinction, uses purpose as the defining criterion. Like the CSTE report, the CDC’s policy also identifies intended beneficiaries as an important consideration. A proposed updated definition for public health surveillance introduced the phrase “a priori purpose of preventing or controlling disease or injury.”5(p636) This emphasis on the original intent for data collection, analysis, and interpretation further demarcates public health activities from research activities employing similar methods.5 This distinction is also relevant to the sharing of information, which is vital to public health practice.

Although publication per se is not used by some authorities (such as the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Human Research Protections) to define research, others view the intent to publish findings in peer-reviewed medical journals as almost exclusively a function of human participant research.6,7 Prospective authors may encounter resistance from institutions that consider all publication as research, or from scientific journals requiring assurances of human participant protection. Although established standards8 for manuscript submission do not prohibit the publication of findings generated from the practice of public health, there is no specific provision for the publication of scholarly work that is not typical human participant (or animal) research.

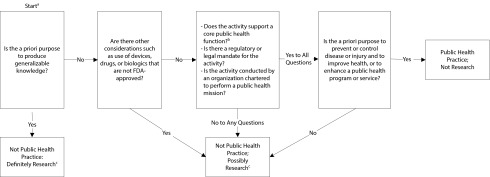

Although CSTE and CDC position statements on public health practice and research are instructive, a mechanism to operationalize their guidance in an explicit, defensible, and reproducible manner is lacking. Thus, institutions with operational missions that include public health services and human participant research may struggle to feasibly and consistently manage their public health activities while complying with research regulatory requirements. We propose an algorithm, illustrated in Figure 1, for the adjudication of activities common to research and public health practice that could assist public health practitioners, research oversight authorities, scientific editors, and others in determining whether such activities require regulatory review and approval as research.9 The algorithm builds on current CDC policy but adds clear questions to guide decision-making, which should provide practical assistance and should result in more consistent decisions. Constructed around the a priori purpose for which an activity was designed, the algorithm begins with whether the a priori purpose of an activity is to produce generalizable knowledge, considers special Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issues, poses questions about the regulatory and legal mandate and mission of an activity, and confirms the a priori purpose as public health practice.

FIGURE 1—

Algorithm for distinguishing public health practice from public health research.

Note. FDA = US Food and Drug Administration.

aThe algorithm assumes that the activity under question is a systematic investigation.

bCore public health functions include assessment, policy development, and assurance.9

cManage by research infrastructure serving the institution, possibly including an institutional review board. Refer to decision checklists for research suggested by Office for Human Research Protections, Department of Health and Human Services (http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/checklists/decisioncharts.html).

CASE STUDIES

Three areas of public health practice—surveillance, emergency response, and program evaluation—have been identified as problematic, given their potential overlap with research.2 From the perspectives of the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 2 agencies with extensive health systems that include direct patient care, public health, and human participant research activities, we present several case studies pertaining to these areas to illustrate the challenges of differentiating public health practice from research. We also discuss an operational approach, using the framework illustrated in Figure 1, for distinguishing these activities. We begin by describing DoD and VA policies to provide context for understanding the case studies.

Department of Defense

Department of Defense agencies conducting research are guided by the Common Rule, as described in 32 CFR 219, “Protection of Human Subjects.”10 Other documents describe roles, responsibilities, and clinical research policies for activities conducted by the Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force.11,12 Public health practice in the military, however, is not explicitly described in any comprehensive DoD policy directive or instruction. Activities labeled “force health protection” include traditional public health activities, such as needs assessment, surveillance, early detection of health threats, and emergency response.13 The DoD also provides policy guidance for response to public health emergencies, including isolation, quarantine, and outbreak and case notification procedures.14

The US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and the Navy Medical Research Command, whose core functions involve research and product development, periodically support the public health mission by lending professional expertise and specialized technical capabilities, such as infectious disease laboratories.

Department of Veterans Affairs

The Veterans Health Administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs has an Office of Public Health, whose activities include (1) surveillance and (2) outbreak and look-back investigations in the VA. (“Look-back” is an organized process for identifying patients who may be at risk because of exposure incurred through past clinical activities.) The VA Office of Research Oversight has defined nonresearch public health activities in the VA as operational endeavors that fulfill 2 requirements: (1) the activity is designed or implemented for internal VA purposes and (2) the activity is not designed to produce information that expands the knowledge base of a scientific discipline or other scholarly field. This may include public health investigations, internal quality improvement projects, and routine data collection and analysis for operational monitoring, evaluation, and program improvement. Data collected for nonresearch operations may subsequently become research if they expand the knowledge base of a scientific discipline or scholarly field.

Activities always considered research by the VA are those funded or otherwise supported as research by the VA Office of Research and Development, or by any other entity, and clinical investigations as defined under FDA regulations.

Surveillance

Public health surveillance can be defined as the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of health-related data with the a priori purpose of preventing or controlling disease or injury.5 Most surveillance activities are mandated or authorized by state statute and do not require IRB approval. For example, monitoring health-related events during the Deep Water Horizon oil spill or the emergence of dengue virus infections in south Florida have been considered nonresearch operational activities and not contingent on IRB review.15,16 In these situations, the VA was asked to assist public health authorities in an interjurisdictional assessment of possible illness associated with oil exposure and the extent of emergent endemic dengue virus infections, respectively. By the algorithm in Figure 1, both activities would be considered core public health functions without a prior intent of producing generalizable knowledge. However, the information derived from these surveillance activities was considered important information for public health practitioners and disease experts and was therefore presented at scientific meetings.

Unlike these examples, some surveillance activities can be regarded as both research and public health practice. The Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) serves as a central repository of health surveillance data for the US Armed Forces to monitor the occurrence and distribution of health conditions in the US military population.17 Although its major function is public health, the DMSS is also used for research purposes. For instance, the DMSS has been employed for research on infectious gastroenteritis-related reactive arthritis,18 anthrax vaccination and risk of optic neuritis,19 and mild traumatic brain injuries among US service members.20 The use of the DMSS is governed by policy21 established by its parent organization, the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC), which in turn reflects DoD policies and regulations on privacy, data management, public health, and human participant research. The AFHSC policy provides specific guidance for managing requests (classified as research or operational; i.e., public health practice) for DMSS data and serum specimens stored in the DoD Serum Repository through a procedure resembling but not identical to that outlined in Figure 1. Each of the studies mentioned here were determined to be research since they were designed to generate knowledge applicable to populations beyond the US military or to contribute new information about a health condition. These studies and others like them require IRB approval and research management support external to the AFHSC, and are referred elsewhere for appropriate research review and approval. Requests for data or sera that are judged by the AFHSC to constitute operational or public health practice are evaluated for feasibility and scientific merit by an internal board, which is not a human participant research IRB. These examples using the DMSS underscore the importance of the a priori purpose for which an activity was designed rather than the organization conducting the work. A traditional research institution could be engaged in public health practice, whereas a public health organization could be engaged in research.

Emergency Response

Emergency responses, including outbreak investigations, can be defined as public health activities undertaken in an urgent or emergent situation, usually involving an imminent health threat to the population.22 They are intended to determine the nature and magnitude of a public health problem and to implement appropriate response measures,23 and must be distinguished from research undertaken in emergency settings or disasters, which also poses unique ethical and operational challenges.24 Although emergency response activities fall within the purview of public health authority—and are often mandated by law or regulation—IRB requirements are often uncertain and inconsistently applied, as illustrated by the following examples.

Report of an outbreak investigation of African tick typhus among soldiers in Botswana did not mention IRB review or oversight. In this outbreak of tick typhus, work was initiated as an investigation of an outbreak: “An epidemiologic team from Walter Reed Army Institute of Research [WRAIR] was sent to Botswana to assist with the outbreak investigation.”25(p217) The original intent was not to produce generalizable knowledge but to understand and mitigate the outbreak. Although WRAIR is primarily a research organization, at the time of the outbreak in 1992, it was tasked by the surgeon general of the US Army to apply its subject matter expertise (personnel and laboratory capabilities) to nonresearch activities in the form of an epidemiological consultation, or EPICON. The investigation involved no FDA regulatory concerns, fell under the mandate and mission of WRAIR, and supported a core public health function. Application of the algorithm in Figure 1 consequently categorizes this work as public health practice, consistent with the lack of IRB involvement.

Whereas the investigation of tick typhus was undergirded by a singular public health purpose to control disease, the response to an outbreak of adenovirus type 14 (Ad14) among recruits at Lackland Air Force Base in 2007 was more complicated. In this Ad14 outbreak investigation, the intent was stated explicitly by the authors: “We investigated this cluster of Ad14 cases … with the intent of clarifying the public health risk and implementing control measures.”26(p1420) The intent of the outbreak investigation defines it as public health practice. In addition, there were no FDA regulatory considerations, the investigation supported a core public health function, and it was led by the CDC, which has a legal mandate for such activities. However, as part of the outbreak investigation, additional studies were conducted that could be construed as research. “Because a new vaccine against Ad7—a serotype antigenetically related to Ad14—[was] under development,” the investigators also “sought to determine whether naturally acquired neutralizing antibodies to Ad7 would also provide some protection against severe Ad14 disease.”26(p1420)

If the a priori purpose of this facet of the investigation was to produce generalizable knowledge, then following the algorithm in Figure 1, this activity would be deemed research and not public health practice. However, according to the authors, the entire investigation was viewed as “an emergency public health response to an outbreak” and, as such, “no review by the human ethics committee [of the CDC] was required.”26(p1420) This example illustrates the need for vigilance and flexibility in the approach to emergency response scenarios. Research questions often arise in the course of an outbreak investigation, the pursuit of which would require thorough reexamination of agency intentions and objectives, and possible reconsideration of at least some of the activity as research. For example, emergence of a new goal (e.g., examining antibody protection) should dictate a reexamination that could be facilitated by the algorithm in Figure 1. An answer of “yes” to the first question posed by the algorithm would classify this new component as research rather than public health practice.

Unlike the Ad14 investigation, a different approach was taken during an outbreak investigation of norovirus and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli onboard a US Navy ship in 2008. The authors state that the a priori purpose of their work was

to identify the etiologic agent, to evaluate factors associated with the outbreak and to provide recommendations to the ship’s commander on how to control the current and prevent future outbreaks.27

By the algorithm in Figure 1, the initial question would classify the outbreak investigation as public health practice, since the a priori purpose was not to produce generalizable knowledge. Moreover, an IRB is not applicable to a public health response. In actuality, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the IRB affiliated with the US Naval Medical Research Unit Six (NAMRU-6), which determined that the work did not meet the definition of human participant research and waived the need for consent.27 Because Title 45 CFR 46 applies to human participant research only, upon determining that a project does not meet the definition of human participant research, the IRB appears to have had no additional role or responsibility in this case. In addition, no special FDA considerations were mentioned in the article. The question of whether the NAMRU-6 agency (primarily a research institute) has the mandate or mission to conduct public health practice remains. Because the unit has been directly supported to provide this type of response through DoD emerging infectious disease surveillance programs over many years, this kind of work can be justified and can be differentiated from work performed under its research mandate.

Likewise, when it was discovered that patients were potentially exposed to improperly cleaned endoscopes at several VA medical centers, the Veterans Health Administration’s Office of Public Health conducted an epidemiological look-back investigation to determine whether patients could have acquired blood-borne pathogen infections from their exposure.28 Because the investigation required notification, disclosure, and additional blood samples for viral pathogen testing and molecular fingerprinting as part of a public health investigation and not routine clinical care, the question arose as to whether obtaining such samples to determine causality and linkage of infections constituted a research project and therefore required written informed consent before obtaining samples. The VA Offices of Research Oversight, General Counsel, and Medical Ethics determined that this investigation was public health practice and did not constitute research, thus precluding IRB review. This decision is consistent with our algorithm in Figure 1. Although there was no prior intent to produce generalizable knowledge, the findings of this investigation did generate new knowledge regarding risk of infection following infection control breaches, and its publication in the peer-reviewed literature is considered an important contribution.

Program Evaluation

Program evaluation refers to the systematic application of scientific and statistical procedures for measuring program design, implementation, and utility.29 For example, the Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics (ESSENCE), which is used to detect outbreaks and track disease trends, was evaluated by the CDC in an outbreak of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) at the US Air Force Academy in 2009.30 The stated purpose of the evaluation was to assess the performance of ESSENCE during the outbreak, which would classify the activity as public health practice according to Figure 1. Appropriately, there was no mention of IRB review. Although the findings and conclusions about the usefulness, simplicity, flexibility, and other features of ESSENCE in the specific outbreak could be generalizable to other situations, because the a priori purpose was not to produce generalizable knowledge, Figure 1 confirms that the activity was not research.

The VA also used ESSENCE to conduct ongoing influenza biosurveillance for situational awareness within the VA. This activity would be considered standard public health practice. However, the circumstances around the arrival of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) provided the VA with the opportunity to evaluate ESSENCE detection performance and determine whether improvements could be made to existing detection algorithms.31 Likewise, at the Lovell Federal Health Care Center, the VA and the DoD jointly evaluated disease surveillance of combined VA and Navy data.32 Although both activities used resources required for ongoing public health practice and program evaluation, the evaluators ruled that they were distinct from ongoing public health investigations and a priori would produce generalizable knowledge; therefore, according to Figure 1, they would be labeled as research, thus requiring IRB review and approval.

CONCLUSIONS

Public health activities entail both research and public health practice. Distinguishing these 2 realms is often difficult in light of elements common to both. Analyses of several case studies illustrate the difficulties and uncertainty of making this distinction while emphasizing the practical need to do so. It should be noted that our analyses are based only on our reading of the literature as it appears. We drew conclusions from published accounts of events that were reported, rather than what may have actually transpired. Each of the case studies may have involved additional information, details, and deliberations that were not published and therefore not taken into account in our analysis. For example, absence of a specific citation of an IRB review in the published article does not necessarily mean there was no review.

Nonetheless, applying an algorithm constructed around the a priori purpose of an activity provides a mechanism for public health agencies to make valid, defensible, and reproducible decisions regarding the nature of an activity. Our algorithm in Figure 1 operationalizes CDC guidance in an explicit manner, offering a practical and simple tool that should result in more consistent decisions. However, its chief limitation resides in the lack of inherent guidance on how it should be used, namely, who has authority to ascertain each of the questions posed by the algorithm. In addition, even though the algorithm relies upon an honest assessment of a priori purpose, disagreement may still occur among people of integrity. We anticipate that further use of the algorithm will elucidate additional limitations not completely envisioned thus far.

Routine public health activities cannot be implemented in a timely and effective manner if subjected to the substantial administrative burdens and delays associated with an a priori IRB review. Certain public health efforts, such as outbreak investigations, must be executed rapidly to reduce disease transmission. Public health practice would benefit from a mechanism, analogous to those for human participant research, of adequate and consistent ethical oversight. We anticipate that development of independent and dedicated accreditation and certification processes will lead to increased recognition and definition of public health practice that adheres to unique standards, and is not subjected to those misapplied from the research domain. Scientific journals should recognize that an article documenting public health practice does not require IRB approval as research; however, they should ensure that the work performed is consistent with ethical public health practice, is conducted by a governmental institution or delegate duly authorized for such activity, and complies with regulatory and statutory mandates to maintain, protect, and restore community health.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bryant Webber and Susan Ford for their substantial help in reviewing and editing the article.

Human Participant Protection

No institutional review board was needed because the project involved no interactions with human participants.

References

- 1. Title 45 Code of Federal Regulations. Part 46: protection of human subjects. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2007-title45-vol1/pdf/CFR-2007-title45-vol1-part46.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 2.Snider DE, Jr, Stroup DF. Defining research when it comes to public health. Public Health Rep. 1997;112(1):29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodge JG, Jr, Gostin LO. CSTE Advisory Committee. Public health practice vs research: a report for public health practitioners including cases and guidance for making distinctions. 2004. Available at: http://www.cste2.org/webpdfs/CSTEPHResRptHodgeFinal.5.24.04.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s policy on distinguishing public health research and public health nonresearch. 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/od/science/integrity/docs/cdc-policy-distinguishing-public-health-research-nonresearch.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2011.

- 5.Lee LM, Thacker SB. Public health surveillance and knowing about health in the context of growing sources of health data. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(6):636–640. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wedeen RP. Public health practice vs public health research: the role of the institutional review board. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1841. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DiPietro J. Institutional review board. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Available at: http://www.jhsph.edu/sebin/k/b/irb_process_2007-08.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- 8.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. April 2010. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/urm_full.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012. [PubMed]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Title 32 Code of Federal Regulations. Part 219: protection of human subjects. Available at: http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=38d81486398138c7f7ed1c6044318301&rgn=div5&view=text&node=32:2.1.1.1.22&idno=32. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 11. Department of Defense Directive 3216.02: protection of human subjects and adherence to ethical standards in DoD-supported research. November 8, 2011. Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/321602p.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 12. Department of Defense Instruction 6000.08: funding and administration of clinical investigation programs. December 3, 2007. Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/600008p.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 13. Department of Defense Directive 6200.04: force health protection. April 23, 2007. Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/620004p.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 14. Department of Defense Directive 6200.03: public health emergency management within the Department of Defense. June 1, 2012. Available at: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/620003p.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 15. Rangel MC, Martinello RA, Lucero C, et al. Adapting a syndromic biosurveillance system to monitor veterans’ health impact associated with the Gulf Coast oil spill (abstract 585). Paper presented at: International Society for Disease Surveillance Conference; December 1–2, 2010; Park City, UT.

- 16. Lucero CA, Benoit S, Santiago LM, et al. Enhanced provider education and dengue surveillance in Florida Veterans Affairs healthcare facilities, 2009–2010 (abstract 120). Paper presented at: Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) Annual Meeting; April 1–4, 2011; Dallas, TX.

- 17.Rubertone MV, Brundage JF. The defense medical surveillance system and the Department of Defense serum repository: glimpses of the future of public health surveillance. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1900–1904. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curry JA, Riddle MS, Gormley RP et al. The epidemiology of infectious gastroenteritis related reactive arthritis in US military personnel: a case–control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:266–275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne DC, Rose CE, Kerrison J. Anthrax vaccination and risk of optic neuritis in the United States military, 1998–2003. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(6):871–875. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron KL, Marshall SW, Sturdivant RX, Lincoln AE. Trends in the incidence of physician-diagnosed mild traumatic brain injury among active duty US military personnel between 1997 and 2007. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(7):1313–1321. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Policy on requests for information and serum and the protection of human subjects in the performance of surveillance, public health practice, and research. June 15, 2011. Available at: http://afhsc.mil/viewDocument?file=DoDSR_Items/110615_IPM2011-05RequestsPHP.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- 22.Langmuir AD. The Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Center for Disease Control. Public Health Rep. 1980;95(5):470–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman RA, Buehler JW. Field epidemiology defined. In: Gregg MB, Dicker RC, Goodman RA, editors. Field Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tansey CM, Herridge MS, Heslegrave RJ, Lavery JV. A framework for research ethics review during public emergencies. CMAJ. 2010;182(14):1533–1537. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smoak BL, McClain JB, Brundage JF et al. An outbreak of spotted fever rickettsiosis in US Army troops deployed to Botswana. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2(3):217–221. doi: 10.3201/eid0203.960309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate JE, Bunning ML, Lott L et al. Outbreak of severe respiratory disease associated with emergent human adenovirus serotype 14 at a US Air Force training facility in 2007. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(10):1419–1426. doi: 10.1086/598520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzaga VE, Ramos M, Maves RC et al. Concurrent outbreak of norovirus genotype I and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli on a US Navy ship following a visit to Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holodniy M, Oda G, Schirmer PL et al. Results from a large-scale epidemiologic look-back investigation of improperly reprocessed endoscopy equipment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(7):649–656. doi: 10.1086/666345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-11):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessment of ESSENCE performance for influenza-like illness surveillance after an influenza outbreak—US Air Force Academy, Colorado, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(13):406–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schirmer P, Lucero C, Oda G et al. Effective detection of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in US Veterans Affairs medical centers using a national electronic biosurveillance system. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucero CA, Oda G, Cox K et al. Enhanced health event detection and influenza surveillance using a joint Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense biosurveillance application. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]