Abstract

Objectives. We conducted a rapid needs assessment in the Rockaway Peninsula—one of the areas of New York City most severely affected by Hurricane Sandy on October 29, 2012—to assess basic needs and evaluate for an association between socioeconomic status (SES) and storm recovery.

Methods. We conducted a cross-sectional survey within the Rockaways 3 weeks after the hurricane made landfall to elicit information regarding basic utilities, food access, health, relief-effort opinions, and SES. We used a modified cluster sampling method to select households with a goal of 7 to 10 surveys per cluster.

Results. Thirty to fifty percent of households were without basic utilities including electricity, heat, and telephone services. Lower-income households were more likely to worry about food than higher-income households (odds ratio = 4.5; 95% confidence interval = 1.43, 15.23; P = .01). A post-storm trend also existed among the lower-income group towards psychological disturbances.

Conclusions. Storm preparation should include disseminating information regarding carbon monoxide and proper generator use, considerations for prescription refills, neighborhood security, and location of food distribution centers. Lower-income individuals may have greater difficulty meeting their needs following a natural disaster, and recovery efforts may include prioritization of these households.

Hurricane Sandy was a tropical cyclone that made landfall in the Northeastern United States on October 29, 2012. It was reported by meteorologists to be one of the largest Atlantic storms on record, and was classified as a category 3 storm system at its maximum intensity.1,2 It devastated hundreds of miles of coastline, left 8 million homes without power, caused an estimated 50 billion dollars in damages, and resulted in the death of 132 individuals.3,4

The Rockaway Peninsula is located on the Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the borough of Queens in New York City (NYC), and is home to approximately 130 000 individuals. Socioeconomically, Rockaway encompasses luxury summer beachfront houses at its westernmost tip and government housing projects toward the east. Geographically isolated from Manhattan, it was structurally isolated without mass transit until 1956. In the mid-20th century, it transformed into an urban beachfront resort that might be accessible to the poor, simultaneously attracting wealthy city beach-goers. Furthermore, city-sponsored housing projects promoted the movement of minorities, recipients of public assistance, the elderly, and those with psychiatric conditions to the peninsula. This resulted in a unique demographic in a relatively small area.5

IMPORTANCE

Hurricane Sandy caused extensive damage to the Rockaway Peninsula, resulting in fires that destroyed more than 100 homes, widespread power and heat outages, and the closure of health facilities and grocery stores.6 The only hospital that remained open on the peninsula reported a 40% increase in emergency department visits during the immediate aftermath of the storm.7 Although the Rockaways were profoundly affected by the storm, it did not receive the immediate influx of recovery efforts that other areas of NYC (e.g., Manhattan) received. During the citywide recovery effort, individual reports suggested that the Rockaways were neglected, citing the restoration of electricity across the bay in lower Manhattan weeks sooner.8

Rapid needs assessments are conducted as expeditiously as possible following a hurricane in an attempt to quantify, categorize, and stratify disruption of basic human needs.9 Most commonly undertaken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the United States, questionnaires conducted during a hurricane assessment focus on structural damage, displacement, the loss of heat and electricity, health concerns, and food shortages.10–15 Previous studies utilizing this surveillance method highlighted the importance of quantification of basic human necessities immediately after natural disasters to direct aid and relief efforts.16,17

GOALS OF THIS INVESTIGATION

To our knowledge, a comprehensive rapid needs assessment had not yet been performed in the Rockaways 19 days after Hurricane Sandy made landfall. The purpose of our study was to conduct such an assessment in the Rockaway Peninsula using a cross-sectional study design. We included in our survey proxy-variables to measure socioeconomic status (SES) in order to evaluate associations between income and recovery from this natural disaster. Additionally, we included questions regarding government and volunteer relief efforts to elicit opinions regarding perception of their efficacy during the recovery process.

METHODS

The Rockaway Peninsula is on the southern coast of the borough of Queens, within NYC, and it extends into the Atlantic Ocean. It is 11 miles in length, and 0.75 miles in width. A modified cluster approach was utilized to select households within a central, highly populated portion of the Rockaway Peninsula. Each cluster was defined as a 10-block region between Beach 50th street to Beach 150th street, covering roughly half of the peninsula, including 7 of its 11 neighborhoods. Teams were assigned to 10-block clusters with a goal of completing 7 to 10 well-spaced, random household interviews per cluster. Each team began at a randomly selected location within their 10-block radius. They were instructed to select every fifth to seventh household for an interview. When an apartment complex or housing project was encountered, the team selected 1 building and a random floor was selected. Every fifth to seventh apartment was selected until a total of 2 surveys were completed within that complex. The CDC’s Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER) recommends selecting 30 clusters and completing 7 interviews per cluster; however, CASPER typically covers multiple census blocks.18 Given the size of the Rockaway Peninsula, approximately 2 census blocks, we chose to cover a smaller area, surveying 7 of 10 neighborhoods in entirety. The regions chosen were the most highly impacted areas with the exclusion of Breezy Point, which was inaccessible secondary to widespread fires.

When an inhabited household was encountered using our sampling method, any adult aged 18 years or older was invited to participate in the survey. They were given the option to refuse to participate in the study.

Survey enumerators were selected from volunteer registered nurses, social workers, and physicians recruited through the Occupy Sandy movement. Teams of 2 to 3 individuals were sent to each cluster to interview randomly selected households. Training was completed on site each morning before teams were dispatched, and consisted of proper questionnaire administration, personal safety, and instructions for referrals.

Methods and Measurements

A questionnaire was developed from selected questions from the CDC’s CASPER toolkit, specifically from Appendix D “Sample Questionnaire.”18 These questions included those that solicited information regarding demographics, type of housing unit, current source of heat and electricity, and basic health information. All questions were included, however, several questions were added regarding transportation and health. Additionally, questions were added to evaluate opinions regarding the relief effort in the Rockaway Peninsula and to assess SES.

The survey was administered 3 weeks after Hurricane Sandy over a 3-day period from November 17–19, 2012. Immediate needs were relayed to local medical and service volunteer groups as well as the NYC Department of Health. If an emergent medical need was identified, teams were instructed to call 911.

Enumerators were instructed to record response data on all households that were randomized, including those that appeared vacant, nonresponsive, or refused to participate in the survey. Demographics, basic needs, health information, and relief effort opinion were reported as frequencies.

We created an aggregate variable for SES using proxy measures because we intentionally avoided asking for household income out of concern it would compromise the interview. We defined those with the lowest incomes as those who were on government assistance and who were also either on Medicaid or uninsured, or who were unemployed. High income was defined by proxy variables as those with private insurance, employment, car ownership, and not on government assistance. The lowest and highest quartiles of income groups were combined to make a binary aggregate variable for SES.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Results are presented as frequencies with proportions (Table 1). We conducted univariate analysis using logistic regression modeling employing the maximum likelihood theory to evaluate the relationship between individual variables and SES.

TABLE 1—

Survey Population Demographics: Rockaway Peninsula, New York City; November 17–19, 2012

| Variables | Households, No. (%) |

| Age, y (n = 86) | |

| 20–29 | 11 (12.8) |

| 30–39 | 11 (12.8) |

| 40–49 | 20 (23.3) |

| 50–59 | 16 (18.6) |

| 60–69 | 20 (23.2) |

| 70–79 | 4 (4.7) |

| ≥ 80 | 4 (4.7) |

| Gender (n = 91) | |

| Male | 37 (40.6) |

| Female | 54 (59.3) |

| Race (n = 89) | |

| White | 51 (57.3) |

| Black | 23 (25.8) |

| Asian | 6 (6.7) |

| Mixed | 2 (2.2) |

| Other | 7 (7.9) |

RESULTS

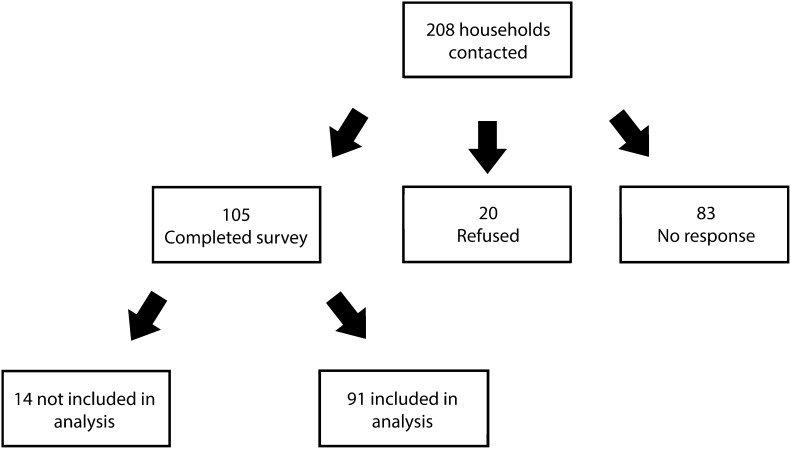

Enumerators visited a total of 208 households on the Rockaway Peninsula (Figure 1). Approximately 40% of households approached did not answer the door, of which 25% appeared vacant. Ten percent of households refused to participate in the study. Information was collected on 105 households with an overall response rate of 51%. Fourteen surveys were excluded from final analysis because of incorrect acquisition and recording of location data, leaving 91 households for inclusion in the final analysis.

FIGURE 1—

Survey response rate: Rockaway Peninsula, New York City; November 17–19, 2012.

Characteristics of Study Participants

There was an even age distribution between ages 20 to 69 years, with a decreased response rate from individuals aged 70 to 79 and 80 to 89 years (Table 1). By race, the respondents were 57% White, 25% Black, 7% Asian, and the remainder were of mixed race or other. Almost 70% were employed with 18% reporting unemployment and 11% in retirement.

During the Hurricane, more than half (57%) of participants reported evacuating their homes (Table 2). Of those who did not evacuate, the most common reason reported was refusal to leave (52%), followed by not knowing where else to go (19%). Only 3 participants stayed because of physical disability, and 1 was unable to find transport.

TABLE 2—

Assessment of Basic Utilities Among Survey Population: Rockaway Peninsula, New York City; November 17–19; 2012

| Variable | Households, No (%) |

| Evacuated home (n = 90) | 51 (56.7) |

| Current electricity source (n = 89) | |

| Without any electricity at time of survey | 28 (31.5) |

| Power company | 49 (55.1) |

| Generator | 12 (13.5) |

| Days without LIPA electricity (n = 81) | |

| 0 | 1 (1.2) |

| 1–7 | 2 (2.5) |

| 8–14 | 14 (17.3) |

| 15–21 | 64 (79.0) |

| Heat source (n = 87) | |

| Without heat at time of survey | 38 (43.7) |

| Propane/gas | 20 (23.0) |

| Wood | 4 (4.6) |

| Space heater/generator | 15 (17.2) |

| Other | 5 (5.8) |

| Don’t know | 5 (5.8) |

| Days without heat (n = 82) | |

| 1–7 | 2 (2.4) |

| 8–14 | 17 (20.7) |

| 15–21 | 63 (76.8) |

| Functional telephone (n = 89) | |

| Yes | 56 (62.9) |

| Don’t know | 4 (4.5) |

| Days without telephone (n = 27) | |

| 1–7 | 1 (3.7) |

| 8–14 | 1 (3.7) |

| 15–21 | 25 (92.6) |

| Main method of transport (n = 89) | |

| Car | 58 (65.2) |

| Bus | 21 (23.6) |

| Train | 4 (4.5) |

| Taxi | 1 (1.1) |

| Other | 1 (1.1) |

| Don’t know | 4 (4.5) |

| Food sourcea | |

| Outside of Rockaways (n = 61) | 29 (47.5) |

| Personal storage (n = 61) | 6 (9.8) |

| Friends/family (n = 60) | 17 (28.3) |

| Donations (n = 61) | 18 (29.5) |

| Other (n = 50) | 13 (26.0) |

| Safetya | |

| House unsafe (n = 89) | 33 (37.1) |

| Neighborhood insecure (n = 89) | 24 (27.0) |

| Neighborhood more unsafe (n = 64) | 31 (48.4) |

| Stated greatest need at 3 wk (n = 87) | |

| Heat | 27 (31.0) |

| Electricity | 25 (28.7) |

| Food | 4 (4.6) |

| Medical | 3 (3.5) |

| Structural | 22 (25.3) |

| Neighborhood recovery | 11 (12.6) |

| Financial | 5 (5.7) |

Note. LIPA = Long Island Power Authority.

Respondents were permitted to select more than 1 answer.

At the time of the survey, 46% reported being without electricity with 14% using generators. Of the 12 households using generators, only 2 households placed them in an unsafe location (1 indoors and 1 in the garage). The majority (79%) of respondents reported electricity loss for 15 to 21 days.

Almost all respondents (97%) reported being without heat at some point after Hurricane Sandy, and the majority (77%) reported being without heat for 15 to 21 days. Forty-three percent of individuals were still without heat at the time of the survey. The 2 most frequently reported alternative heat sources were propane and gas stoves (23%) and electric space heaters from generators (17%). Accordingly, three quarters of respondents (73%) felt that this was dangerous to their health.

Thirty-two percent of respondents reported being without a functional telephone at the time of the survey, the majority (93%) of which reported disruptions in service for 15 to 21 days. Twenty-five percent of participants reported disruptions in cellular service with half of these reporting disruptions for more than 2 weeks.

The main method of transportation among participants was by car (63%), followed by bus (24%). Nineteen participants volunteered the information that they had lost a car during Sandy. However, this question was not specifically asked.

Almost half of respondents (48%) reported purchasing food outside of the Rockaway Peninsula in the weeks following the storm. The second most common food source was through donations (30%) followed by friends and family (28%). Only 8% relied on personal storage of food. About 40% of people reported using a gas grill or a camp stove to prepare food, of whom 5 reported using it indoors and 1 reported using it in the garage.

Twenty-nine percent reported being worried about food at some point after the hurricane. The majority of respondents (94%) had an adequate supply of water for 3 days and 83% used bottled water as their primary source.

More than one third of residents reported feeling that their house was not safe to inhabit with the most frequently reported reason being mold (27%) followed by lack of heat (15%). Almost half of respondents felt that their neighborhoods were unsafe after the storm because of increased crime and looting.

Three weeks after Hurricane Sandy, the residents’ greatest needs included restoration of heat (31%), restoration of electricity (29%), and structural or household recovery (25%). Other needs included neighborhood recovery, as well as food, medical, and financial assistance.

Health

Injuries following Hurricane Sandy were reported by 9% of households, the most common being cuts and falls requiring medical attention (Table 3). Surveyors identified no acutely emergent needs. However, 1 patient was referred to a psychiatrist secondary to severe anxiety and depression. Twenty-nine percent of respondents reported illnesses after the storm, of which the most common were upper respiratory symptoms or pneumonia (81%) followed by febrile illness (23%) and worsening of chronic illnesses (15%). One third of participants were unable to obtain prescription medications after Sandy, and those who did most commonly reported visiting a pharmacy outside of the Rockaways (46%). In the event of a health-related emergency, 44% of participants stated that they would call 911, 37% would seek care in a hospital outside of the Rockaways, and 23% would seek care in a hospital within the peninsula.

TABLE 3—

Health-Related Variables Among Survey Population: Rockaway Peninsula, New York City; November 17–19, 2012

| Health-Related Variables | Households, No. (%) |

| Injuries since storm (n = 90) | 8 (8.9) |

| Illnesses within household since storm (n = 90) | 26 (29.0) |

| Type of illnessa (n = 26) | |

| Upper respiratory symptoms | 21 (80.7) |

| Febrile illness | 6 (23.1) |

| Worsened chronic illness | 4 (15.3) |

| Can you obtain prescription medication? (n = 83) | |

| Unable to obtain | 27 (32.5) |

| Don’t know | 5 (6.0) |

| Location if obtaining medication | |

| Pharmacy in Rockaways | 7 (14.9) |

| Prescription outside Rockaways | 24 (51.1) |

| Hospital | 1 (2.1) |

| Temporary clinic | 5 (10.6) |

| Other | 10 (21.3) |

| Where would you seek medical help if needed?a | |

| Call 911 (n = 87) | 38 (43.7) |

| Hospital in Rockaways (n = 86) | 20 (23.3) |

| Hospital outside Rockaways (n = 86) | 32 (37.2) |

| Health clinic (including temporary; n = 86) | 17 (19.7) |

| No help (n = 86) | 1 (1.2) |

| Carbon monoxide detector | |

| Missing (n = 90) | 14 (15.4) |

| Nonfunctional (n = 75) | 21 (28.0) |

| Did not receive carbon monoxide warning (n = 69) | 33 (47.8) |

| Psychological needs | |

| Anxiety (n = 90) | 58 (64.6) |

| Sleep disturbances (n = 89) | 58 (64.1) |

| Significant emotional concerns (n = 86) | 43 (50.0) |

Respondents were permitted to select more than 1 answer.

Carbon monoxide detectors were missing in 15% of households and reported to be nonfunctional in 28% of homes. Almost half (48%) of households did not receive a warning about the increased risk of carbon monoxide following a natural disaster as a result of inefficient alternative heating and electricity-generating methods.

In regards to psychological needs, anxiety and sleep disturbances were reported by two thirds of respondents (65% and 64% respectively) following Hurricane Sandy. Half of respondents (50%) reported experiencing significant emotional concerns.

Relief Efforts

One third of respondents came into contact with relief organizations more than 10 times. Sixty-eight percent of respondents were given structural assistance, which was defined as any assistance with clearing debris, the provision of tools or cleaning supplies, and the removal of damaged household structures. Sixty-five percent were provided with food, and 22% were provided with medical assistance. Residents came into contact most frequently with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA; 82%), followed by the Red Cross (41%), and then church organizations (32%). The majority of respondents (65%) felt that the relief effort of volunteer organizations (such as Team Rubicon and Occupy Sandy) was excellent, although 19% felt their effort was fair and 4% stated it was poor or terrible. The opinion of government-based relief was reported to be excellent by 23% of respondents, fair by 36%, and poor or terrible by 31%.

Income-Based Modeling

Logistic regression analysis of the SES variable and 10-block clusters demonstrated a statistically significant association between higher SES and increasing 10-block clusters, which correlates well with the known socioeconomic stratification of the Rockaways by geography (odds ratio [OR] = 1.05; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.02, 1.07; P = .001).

Univariate analysis was performed using logistic regression modeling with all variables and SES. There was no evidence for a statistically significant association between SES and electricity source, days without electricity or heat, heat source, or having a functional telephone. There was no statistically significant evidence for an association between SES and injury, illness, or ability to obtain prescriptions 3 weeks after Hurricane Sandy.

Those from a lower SES reported increased psychological stress compared with those from a higher SES, although this did not reach statistical significance (OR = 2.7; 95% CI = 0.93, 8.1; P = .07).

There was evidence of a statistically significant association between SES and concern for obtaining food. Specifically, those from a lower SES household were 4.7 times more likely to report being worried about food after Sandy (95% CI = 1.43, 15.23; P = .01). Utilizing a grocery store outside of the Rockaways was found to have a statistically significant association with SES. Those from higher SES households were 4.5 times more likely to leave the Rockaways to obtain food compared with those from lower SES households (95% CI = 1.11, 17.90; P = .024).

DISCUSSION

The results of this survey demonstrate that Hurricane Sandy led to the disruption of many core elements of participant’s lives, safety, and health. Despite recovery efforts that started immediately after the hurricane receded and the city government’s promise of prompt return of electricity and subway service, we found many households were without basic public utilities 3 weeks after the storm.19 There were major needs for restoration of electricity and heat because of an average outdoor temperature of 7°C for the 3 weeks after Sandy, coupled with several days of below freezing temperatures.20 Hypothermia-prevention protocols call for indoor temperatures of at least 15°C.21 This was subjectively reinforced by respondents citing the lack of heat as an immediate risk to their health. Several responded with stopgap measures to heat their homes, which can increase the risk of fire and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Storm preparedness appeared to be lacking for certain high-risk health behaviors and for neighborhood security. Almost half of our respondents did not receive notification or education about carbon monoxide risks and the avoidance of high-risk behaviors. Improper generator placement with indoor burning of fossil fuels and the use of gas-cooking stoves to heat homes in this setting can increase the risk of carbon-monoxide-associated morbidity and mortality.22 With regards to security, half of the respondents felt that their neighborhoods were no longer safe, citing looting as a primary concern. This has been associated with poor lighting in previous studies and can be attributed to the persistent loss of electricity, which might be remedied by more aggressive stopgap placement of floodlights.23

The assessment of health-related problems included a relatively high number of individuals with respiratory conditions as compared with other post-hurricane studies.24,25 This may partly be attributed to the seasonality of pathogens in the Northeastern United States in November, which is considered late in the hurricane season cycle.26 Many respondents had difficulty acquiring prescription medications, and one third reported that if help were needed they would have to venture outside the Rockaways. This is likely secondary to the devastation of the health care infrastructure, disruption of regular transportation, and lack of individual preparedness for the length of pharmacy and clinic closures. In fact, because of the deleterious health effects of Hurricane Sandy, Doctors Without Borders created their first mission ever within the United States.27

Other studies reported an increase in the incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in natural disaster victims. Our study did not meet the temporal requirements for these diagnoses, although the data suggest that this could be a considerable risk in the future.28,29

We assessed relief efforts by subjective questions on how the interviewees felt their needs were met by various organizations. The volunteer relief effort was given a more frequent report of being “excellent” compared with the government effort. This did not vary by location or SES. During the surveying process, conversations with several people revealed they felt that government presence was delayed and lacking. This was demonstrated anecdotally in news reports and personal reports of FEMA closing offices because of safety concerns during the nor’easter that hit NYC only several days after Hurricane Sandy, leaving only volunteer organizations to handle the crisis.30,31

The relationship between income and response to disaster has been previously examined, with studies demonstrating that those from lower SES suffer greater psychological stress, are more likely to fall through the cracks during relief efforts, and struggle with post-disaster recovery.32,33 In our study, Hurricane Sandy caused significant and uniform disruption in infrastructure to all areas regardless of SES, but 2 associations with SES were found to be significant. First, it suggested that those from lower SES were more likely to worry about food and less likely to obtain food from outside the Rockaways. This could be a result of the persistent, complete disruption in public transportation and the loss of personal vehicles by flooding.34 Second, there was a trend for those from a lower SES to have increased significant psychological stress, a relationship that has been suggested in other studies.35 Although this relationship is complex, it is in part attributed to high secondary stress attributed to long-standing poverty that can be compounded by the acute stress of a natural disaster.36

Limitations and Strengths

This study has limitations. The sampling method was not a true 2-stage cluster sampling method where households that appear vacant are revisited several times in attempts to obtain a completed survey. Our approach may have introduced selection bias. For example, there may have been overselection of those who returned home as compared with those who evacuated, leading to underrepresentation of those without electricity and heat. Additionally, the elderly and young may have been displaced and therefore underrepresented. It may be argued that our response rate was slightly lower than expected, although there are similarly documented response rates in other hurricane needs assessments.24 While there may be the potential for selection bias given our small sample size, population displacement, inability to reach hard-hit areas, and surveying during daylight hours, it would likely result in an underestimation of individuals without basic utilities in the aftermath of the storm.

Enumerators were selected from volunteers who were trained on site, possibly leading to different methods of ascertaining information, which could lead to inter-observer variability. This could lead to artificially increased variability in respondent answers or inaccuracy in our measurements of some questions.

Because of safety concerns in certain locations of the Rockaways, we were unable to send teams to the lower 30 blocks of the peninsula, leading to an underrepresentation of lower-income individuals. This sampling bias could diminish the power of our logistic regression analysis. Additionally, because of transportation barriers we were unable to send enumerators into Breezy Point, one of the hardest hit communities within the Rockaways where more than 100 homes were destroyed by electrical fire.19 This could result in underestimation of the participants without electricity, heat, phone services, and access to food. Finally, all rapid needs assessment tools are limited by their temporal constraints, and the disaster itself, because of areas that were difficult to access, lack of electricity, and security measures.

The strengths of this study include an established systematic post-hurricane survey methodology, fairly comprehensive coverage of an urban oceanfront peninsula that was severely affected, and sufficient sample size for analysis with information about SES. It is one of only a handful of methodologically sound studies of such events in the United States. The purpose of a health needs assessment is to provide data that help prioritize the content of relief efforts and locations of greatest need. It is important to note that the findings from this rapid needs assessment provided information regarding basic utilities stratified by 10-block clusters. The actual data we obtained were rapidly relayed to the New York City Department of Health to better inform and direct their relief efforts.

Conclusions

Hurricane Sandy destroyed services and infrastructure that were essential for maintaining the health and security of the community. This survey conducted 3 weeks after the storm adds new quantitative data to a limited body of evidence derived from the CDC post-hurricane assessment tool, CASPER.11,12,14,15 It also provides information regarding the impact of natural disasters stratified by SES. Our small sample size may contribute to bias, but this is an inherent limitation of a needs assessment tool conducted after a natural disaster. Our findings suggest that the restoration of locally delivered food supplies and of basic utilities should be a priority. Furthermore, the absence of police presence and light led to a heightened sense of insecurity, which may be ameliorated by rapid deployment of floodlighting and increased security measures. We observed an inadequate awareness of the dangers of carbon monoxide poisoning and fire from in-house propane and gas ovens. We also observed a substantial shortfall in personal medication stores and availability. In the future, when natural disasters are anticipated, public health officials should consider focusing on intensive public health education and preparedness, including timely information and warnings about the dangers of carbon monoxide in the home from alternate heating sources, as well as the need to ensure an adequate personal store and supply of necessary medications. Health care recovery efforts should assist those who may have difficulty with access to care, such as the elderly and the debilitated.

Finally, as highlighted in previous sociological studies, those from lower socioeconomic classes may be more severely affected by natural disasters.32,37 Our study suggested this group might have increased difficulties accessing food and coping with emotional stress during the recovery period. Immediate response and subsequent recovery organizations might consider identifying and possibly stratifying households based on these variables.

Further research is also needed to explore associations with socioeconomic status and long-term recovery from hurricanes, focusing on physical health, psychosocial needs, and financial recovery. Additionally, research is needed to further explore interventions to improve outcomes among households that are acutely vulnerable after natural disasters either through isolation, illness, or geographical location.38

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Occupy Sandy for providing volunteer enumerators for this project. We acknowledge Diana Costine for her key insight and advice. We would also like to thank Wallace Carter, MD, Anne Hoffman, and Sunday Clark, ScD, for providing unfaltering administrative support and academic guidance for this project.

Human Participant Protection

This project was determined to be exempt by the Columbia University institutional review board (AAAK9951). There were no participant identifiers collected or questions regarding HIPAA protected sensitive information.

References

- 1. Shukman D. Hurricane Sandy “largest storm recorded in Atlantic.” BBC News. October 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-20128931. Accessed January 22, 2014.

- 2.Newman A. Hurricane Sandy vs. Hurricane Katrina. The New York Times. 2012 Available at: http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/27/hurricane-sandy-vs-hurricane-katrina/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0. Accessed June 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutro R. NASA—Hurricane Sandy (Atlantic Ocean) Greenbelt, MD: NASA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hurricanes and Tropical Storms (Hurricane Sandy). The New York Times. 2012. Available at: http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/h/hurricanes_and_tropical_storms/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2013.

- 5.Kaplan LK. Between Ocean and City: The Transformation of Rockaway, New York. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2003. p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilgannon SD. Wind-driven flames reduce scores of homes to embers in Queens Enclave. The New York Times. 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/31/nyregion/wind-driven-flames-burn-scores-of-homes-in-queens-enclave.html. Accessed June 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. St. John’s Episcopal Hospital Recovers from Sandy. Episcopal Health Services. 2012. Available at: http://www.ehs.org/Press-Center/News/2012/St-Johns-Episcopal-Hospital-Recovers-from-Sandy.aspx. Accessed June 16, 2013.

- 8.Maslin S. In sight of Manhattan skyline, living forlorn and in the dark. The New York Times. 2012 Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/05/nyregion/in-sight-of-manhattan-skyline-a-population-lives-forlorn-and-in-the-dark.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed June 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noji EK. Disaster epidemiology: challenges for public health action. J Public Health Policy. 1992;13(3):332–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noji EK, Baxter PJ, Churchill RE, Etzel RA, Flynn BW, French JG. The Public Health Consequence of Disaster. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. xiv–xv. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid assessment of health needs and resettlement plans among Hurricane Katrina evacuees–San Antonio, Texas, September 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(9):242–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid needs assessment of two rural communities after Hurricane Wilma–Hendry County, Florida, November 1-2, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(15):429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for injuries and illnesses and rapid health-needs assessment following Hurricanes Marilyn and Opal, September-October 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45(4):81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center for Disease. Control and Prevention, Rapid community health and needs assessments after Hurricanes Isabel and Charley–North Carolina, 2003-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(36):840–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid health needs assessment following hurricane Andrew–Florida and Louisiana, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(37):685–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redmond AD. ABC of conflict. Needs assessment of humanitarian crises. BMJ. 2005;330:1320–1322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7503.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lillibridge SR, Noji EK, Burkle FM., Jr Disaster assessment: the emergency health evaluation of a population affected by a disaster. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(11):1715–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER) Toolkit. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coscarelli J. Breezy Point Leveled by Rain and Flames in Hurricane Sandy. New York Magazine. 2012 Available at: http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2012/10/breezy-point-leveled-by-hurricane-sandy.html. Accessed June 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weather History and Data Archive. Available at: http://www.wunderground.com/history. Accessed June 18, 2013.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypothermia-Related Deaths- United States- 1999-2002, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(10):282–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Carbon monoxide exposures after hurricane Ike—Texas, September 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(31):845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Painter K. The influence of street lighting improvements on crime, fear and pedestrian street use, after dark. Landsc Urban Plan. 1996;35(2-3):193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayleyegn T, Wolkin A, Oberst K et al. Rapid assessment of the needs and health status in Santa Rosa and Escambia counties, Florida, after Hurricane Ivan, September 2004. Disaster Manag Response. 2006;4(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee LE, Fonseca V, Brett KM et al. Active morbidity surveillance after Hurricane Andrew–Florida, 1992. JAMA. 1993;270(5):591–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowell SF, Ho MS. Seasonality of infectious diseases and severe acute respiratory syndrome-what we don’t know can hurt us. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(11):704–708. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01177-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honan E. Sandy inspires first Doctors Without Borders US relief effort. Reuters. November 8, 2012 Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/09/storm-sandy-doctors-idUSL1E8M90GK20121109. Accessed January 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madakasira S, O’Brien KF. Acute posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of a natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(5):286–290. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DNAinfo Staff. FEMA Disaster Centers Shut Doors “Due to Weather.” DNAinfo, November 7, 2012. Available at: http://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20121107/tottenville/staten-island-fema-disaster-center-shuts-doors-due-weather. Accessed June 21, 2013.

- 31.Topino J. Bad Sign: FEMA office on Staten Island closes “due to weather.”. New York Post. November 8, 2012 Available at: http://www.nypost.com/p/news/local/staten_island/it_bad_sign_for_staten_GDyn7duXSlTbTxAkrjIHBM. Accessed June 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fothergill A, Peek LA. Poverty and disasters in the United States: a review of recent sociological findings. Nat Hazards. 2004;32(1):89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masozera M, Bailey M, Kerchner C. Distribution of impacts of natural disasters across income groups: a case study of New Orleans. Ecol Econ. 2007;63:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marritz I. Next post-Sandy challenge: the sea of damaged cars. All Things Considered. National Public Radio. December 8, 2012. Available at: http://www.npr.org/2012/12/08/166777949/next-post-sandy-challenge-the-sea-of-damaged-cars. Accessed January 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter MR, Little PD, Mogues T, Negatu W. Poverty traps and natural disasters in Ethiopia and Honduras. World Dev. 2007;35(5):835–856. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa Y, Shaw R. Social capital: a missing link to disaster recovery. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters. 2004;22(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]