Abstract

A rapid, efficient, and catalyst-free click chemistry method for the construction of 64Cu-labeled PET imaging probes was reported based on the strain-promoted aza-dibenzocyclooctyne ligation. This new method was exemplified in the synthesis of 64Cu-labeled RGD peptide for PET imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression in vivo. The catalyst-free click chemistry reaction proceeded with a fast rate and eliminated the contamination problem of the catalyst Cu(I) ions interfering with the 64Cu radiolabeling procedure under the conventional Cu-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition condition. The new strategy is simple and robust, and the resultant 64Cu-labeled RGD probe was obtained in an excellent yield and high specific activity. PET imaging and biodistribution studies revealed significant, specific uptake of the “click” 64Cu-labeled RGD probe in integrin αvβ3-positive U87MG xenografts with little uptake in nontarget tissues. This new approach is versatile, which warrants a wide range of applications for highly diverse radiometalated bioconjugates for radioimaging and radiotherapy.

Keywords: PET imaging probe, 64Cu radiolabeling, catalyst-free click chemistry, integrin αvβ3, in vivo

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear imaging technique used to map biological and physiological processes in living subjects.1−3 Unlike morphological imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT), PET requires the injection of molecular probes in a tested subject in order to acquire the imaging signal from molecular probes labeled with positron-emitting radionuclides.4,5 Fluorine-18 and cabon-11 are two conventional PET radionuclides used for the development of PET imaging probes. Due to the short half-lives of fluorine-18 (109.8 min) and cabon-11 (20.3 min), 18F- or 11C-labeled PET probes must be radiosynthesized with the need for an on-site cyclotron, and the PET imaging of a subject using 18F- or 11C-labeled PET probes must be performed within a few hours.6 In addition to 18F and 11C, several nonconventional metallic radionuclides, such as 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr, have been applied to PET probes.7 These metallic PET isotopes are usually characterized by longer half-lives, allowing the evaluation of radiopharmaceutical kinetics in the same subject to be achieved by successful PET imaging over several hours or even days. Among these metallic radionuclides, 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h; β+ 655 keV, 17.8%) has attracted considerable interest because of its favorable decay half-life, low β+ energy, and commercial availability.8−10 As the half-life of 64Cu is relatively short, fast, clean, and reliable chemistry which can proceed efficiently under mild condition is required for 64Cu labeling of biomolecules. The exploration of new 64Cu-labeling methods using a simple, versatile, and modular approach is thus highly demanded.

Click chemistry offers chemists a platform for general, modular, and high yielding synthetic transformations for constructing highly diverse molecules.11 The Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction, which fuses an azide and an alkyne together, and provides access to a variety of five-membered heterocycles, has become of great use in labeling studies, in the development of new therapeutics and nanoparticles, and in protein modification.12−15 However, the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction often requires the presence of catalytic amounts of nonradiolabeled Cu(I) ions, which interfere with radiometals, such as 64Cu, and make click reaction unfavorable for the development of radiometal-labeled PET probes. With the recent discovery of Cu(I)-free 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions,16,17 several strain-promoted systems, such as cyclooctynes and dibenzocyclooctynes, have been developed for 18F labeling,18,19 but few examples were reported in radiometal labeling.20 One elegant study was to use a Diels–Alder reaction (norbornene-tetrazine ligation) to prepare 64Cu-labeled antibodies.21 To the best of our knowledge, the catalyst-free aza-dibenzocyclooctyne ligation has not yet been employed in the radiometal-labeled probes. Herein we present a study of using aza-dibenzocyclooctyne ligation—a fast and efficient approach to synthesize 64Cu-labeled probes. A 64Cu-labeled derivative of cyclic RGD peptide [c(RGDfK)] (Figure 1), a well-validated integrin αvβ3 ligand,22−24 was exemplified by using the “click” method. We further demonstrate that our “click” RGD probe maintains good binding affinity to the integrin αvβ3 receptor and exhibits excellent tumor targeting and retention properties in an integrin αvβ3-positive mouse tumor model.

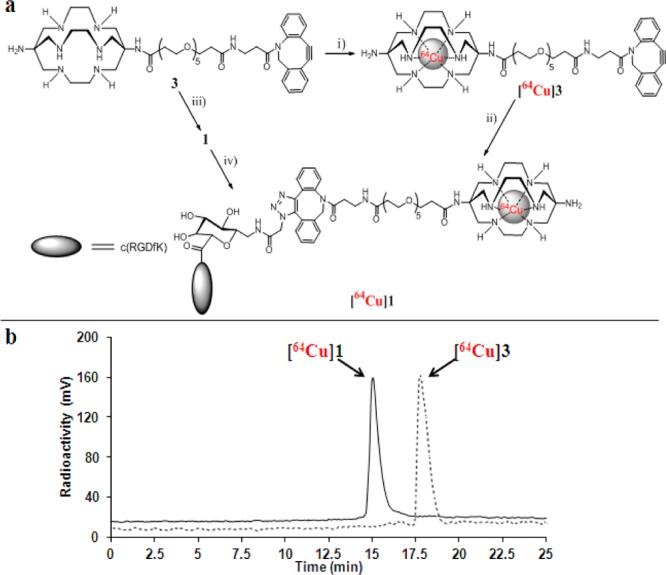

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of relevant RGD peptides.

Our starting point was to select a suitable azide moiety containing RGD peptide. It was found that glycosylation on the lysine side chain of cyclic RGD peptides decreased lipophilicity and hepatic uptake.25 This finding prompted us to consider methods for preparing azido galacto-RGD peptide. To this end, we synthesized 2 as shown in Figure 1. The fully protected c[R(Pbf)GD(OtBu)fK] peptide was conjugated with Fmoc-protected galacturonic acid derivative, followed by deprotection of the Fmoc group, azido acetic acid coupling, and deprotections of guanidine and acid (Supporting Information). The synthesis was achieved in four steps with a total yield of 44%. We successfully obtained 2 in a great chemical purity (>95%) without HPLC purification.

We next sought to select a suitable 64Cu-chelator complex system, which can be readily conjugated with a strained alkyne. Various bifunctional chelators (BFCs), including widely used cyclam and cyclen backbones-based chelators and cross-bridged tetraamine ligands, have been developed for 64Cu labeling.8−10,26 Recently, a new class of BFCs, based on the cagelike hexaazamacrobicyclic sarcophagine, has gained great attention as potential 64Cu chelators. We and others demonstrated that either one of the primary amines of 3,6,10,13,16,19-hexaazabicyclo[6.6.6]eicosane-1,8-diamine (DiAmSar) or both primary amines could be modified and coupled with biologically relevant ligands.27−29 The resulting 64Cu complexes present improved in vivo stability and radiolabeling efficiency. On the other hand, an aza-dibenzocyclooctyne system has been proved to be simultaneously reactive and stable.30 Therefore, we attempted to build a DiAmSar-containing dibenzocyclooctyne analog as a strained alkylne as well as a 64Cu labeling precursor. In addition, because a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) linker can fine-tune the in vivo pharmacokinetics of imaging probes,31,32 we aimed to incorporate a PEG linker between DiAmSar and dibenzocyclooctyne. Our synthesis started from commercially available dibenzocyclooctyne, which was coupled with a short PEG linker. After the activation of the carboxylic acid group, the PEG-dibenzocyclooctyne was conjugated to the commercially available DiAmSar in basic sodium borate buffer to afford 3 in 45% yield (Supporting Information). Radiolabeling of 3 with 64Cu was efficiently accomplished at 40 °C in 0.4 M NH4OAc buffer within 30 min (Figure 2a and Supporting Information). The product [64Cu]3 was purified by HPLC. The radioactive peak containing [64Cu]3 appeared at 17.67 min, as shown in Figure 2b. The specific activity of [64Cu]3 was estimated to be 37 MBq·nmol–1.

Figure 2.

(a) Synthesis of [64Cu]1. Reagents and conditions: (i) 64CuCl2, 40 °C, 0.4 M NH4OAc; (ii) RGD peptide 2, 45 °C, H2O; (iii) RGD peptide 2, room temperature, H2O; (iv) 64CuCl2, 40 °C, 0.4 M NH4OAc. (b) Radio-HPLC profiles of [64Cu]1 and [64Cu]3.

To optimize the conjugation between 2 and [64Cu]3, we systematically investigated the coupling efficiency under various reaction conditions by changing reaction factors, including reactant stoichiometry, solvent, reaction time, and reaction temperature. The conjugations between 2 and [64Cu]3 were initially carried out in deionized water and analyzed by analytical HPLC. When [64Cu]3 (3.7 Mbq, 1 μM) was mixed with a large excess of 2 (>100-fold) at room temperature, [64Cu]3 was rapidly consumed within 10–15 min, and [64Cu]1 (tR = 15.05 min, Figure 2b) formed in >92% radiochemical yield (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). With a small excess of 2 (5.7-fold), the radiochemical yield was decreased to 42% after combining 2 and [64Cu]3 for 10 min at room temperature (entry 3). However, the elevated temperature (45 °C) significantly enhanced the [64Cu]1 yield (>98%, entry 4) after 10-min mixing of 2 and [64Cu]3. With prolonged reaction time (15 min), an excellent radiochemical yield (>98%) of [64Cu]1 was still achieved by using a 1.14:1 ratio of 2 and [64Cu]3 (entry 5). Further reducing the concentration of 2 and [64Cu]3 resulted in a low [64Cu]1 yield (16%, entry 6). We also investigated the efficiency of the conjugation between 2 and [64Cu]3 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). As shown in entry 7, [64Cu]1 was formed in a quantitative yield at 45 °C within 15 min. Among the explored reaction conditions, coupling of 2 and [64Cu]3 with a 1.14:1 ratio at 45 °C for 15 min in deionized water or PBS buffer exhibits the highest conjugation efficiency. In addition, after coupling of 2 and [64Cu]3, we did not observe any major side product peaks in HPLC analysis, indicating that the catalyst-free click reaction was rather clean and no free 64Cu was released during radiolabeling.

Table 1. Optimization of Synthesis of [64Cu]1 through the Strain-Promoted Catalyst-Free Conjugation between 2 and [64Cu]3.

| entry | 2 (μM) | [64Cu]3a | solvent | temp (°C) | reaction time (min) | radiochem yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 228 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | H2O | 25 | 15 | >98 |

| 2 | 114 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | H2O | 25 | 10 | 92 |

| 3 | 5.7 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | H2O | 25 | 10 | 42 |

| 4 | 5.7 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | H2O | 45 | 10 | >98 |

| 5 | 1.14 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | H2O | 45 | 15 | >98 |

| 6 | 0.29 | 1.85 MBq (0.5 μM) | H2O | 45 | 10 | 16 |

| 7 | 1.14 | 3.7 MBq (1 μM) | PBS buffer | 45 | 15 | >98 |

The concentration was estimated based on the specific activity of [64Cu]3 (37 MBq·nmol–1), taking into account a correction of radioactive decay.

To compare with “click” labeling of [64Cu]1, direct labeling of 1 with 64Cu was also conducted (Figure 2a). The conjugation of 2 and 3 was initially carried out at room temperature. As anticipated, RGD peptide 1 was formed rapidly in an excellent yield (95%) after HPLC purification (Supporting Information). Radiolabeling of 1 with 64Cu could be achieved at 40 °C in 0.4 M NH4OAc buffer within 30 min. The HPLC retention time (15.05 min) of product from direct 64Cu labeling of 1 was consistent with that of “click” 64Cu labeling product (Figure 2b), suggesting the products from two labeling methods were identical. It is also noteworthy that the specific activity of [64Cu]1 from the direct labeling method (30–37 MBq·nmol–1) was close to that from the “click” labeling approach (30 MBq·nmol–1).

The in vitro stability of [64Cu]1 was evaluated after 1, 6, and 24 h of incubation in PBS or mouse serum by radio-HPLC (Figure S1). Chromatographic results demonstrated no release of 64Cu from the conjugate over a period of 24 h. This high stability is attributed to a Sar cage in the conjugate. The octanol/water partition coefficient (log P) for [64Cu]1 was determined to be −1.94 ± 0.10 (Supporting Information), suggesting that [64Cu]1 is rather hydrophilic. In addition, it is known that the U87MG human glioblastoma cell line overexpresses integrin αvβ3 receptor.33 Therefore, we used the U87MG cells to measure the integrin αvβ3 binding affinity of 1 by a competitive cell-binding assay,33 where 125I-echistatin was employed as integrin αvβ3-specific radioligand for competitive displacement. The IC50 values of c(RGDyK) and 1, which represent the concentrations required to displace 50% of the 125I-echistatin bound to the U87MG cells, were determined to be 105 ± 5 nM and 170 ± 3 nM, respectively (Figure S2). The slightly decreased integrin αvβ3 binding of 1 as compared to c(RGDyK) indicates a minimum impact of a long tail (containing galactose, triazole, and Sar moieties) on the binding of c(RGDfK) to integrin αvβ3 receptors.

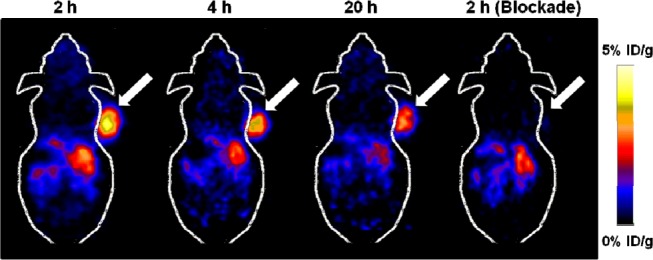

The in vivo tumor-targeting efficacy of [64Cu]1 was evaluated in nude mice bearing U87MG human glioblastoma xenograft tumors (n = 5) by static microPET scans at 2, 4, and 20 h after tail-vain injection of [64Cu]1. Representative coronal slices that contained the tumor are shown in Figure 3. U87MG tumors were clearly visualized at all time points examined. Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis on microPET images showed the tumor uptake values were 4.96 ± 0.73, 4.11 ± 0.54, and 2.41 ± 0.31%ID/g at 2, 4, and 20 h postinjection (pi), respectively (Table 2). At 2 h pi, the tumor/muscle, tumor/liver, and tumor/kidneys ratios reached 11.88 ± 1.31, 2.85 ± 0.28, and 2.22 ± 0.26, respectively. Consequently, the high tumor-to-normal tissue ratios provided excellent contrast for PET imaging. A blocking experiment was conducted to confirm the integrin αvβ3 specificity of [64Cu]1. In the presence of a blocking dose (10 mg/kg) of c(RGDyK), the U87MG tumor uptake was reduced to the background level (0.71 ± 0.30%ID/g) at 2 h pi (Figure 3 and Table 2). The uptake values of normal tissues (e.g., muscle, liver, and kidneys) were also lower than those without coinjection of c(RGDyK) (Table 2). The ex vivo biodistribution of [64Cu]1 was examined in U87MG tumor-bearing mice at 20 h pi after a microPET scan with and without coinjection of c(RGDyK) (10 mg/kg of mouse body weight). The percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) was shown in Figure S3. The biodistribution results were consistent with the quantitative analysis of microPET imaging. At 20 h pi, the U87MG tumor uptake of [64Cu]1 reached 2.26 ± 0.17%ID/g, whereas the presence of c(RGDyK) peptide significantly reduced the tumor uptake to 0.45 ± 0.12%ID/g (P < 0.01) in the blocking group. In addition, [64Cu]1 displayed little accumulation and retention in liver and kidneys at 20 h pi. For the nonblocking group, 1.21 ± 0.17%ID/g and 0.65 ± 0.11%ID/g remained in the liver and kidneys, respectively. Furthermore, similar to microPET imaging analyses, the presence of c(RGDyK) peptide decreased the overall uptake of [64Cu]1 in most tissues and organs. Based on the biodistribution results, the contrast ratios of tumor to normal organs for the nonblocking and blocking groups were calculated. For the nonblocking group, the ratio of tumor uptake to muscle, liver, and kidneys uptake at 20 h pi was calculated to be 5.65 ± 0.11, 1.87 ± 0.17, and 3.48 ± 0.14, respectively, while the corresponding values for the blocking group were 1.41 ± 0.10, 0.64 ± 0.11, and 0.83 ± 0.13, respectively. Overall, the biodistribution pattern of the 64Cu-labeled “click” RGD probe is quite similar to what we previously obtained for 64Cu-labeled non-“click” RGD probes.27

Figure 3.

Decay-corrected whole-body microPET images of U87MG tumor bearing mice (n = 5) at 2, 4, and 20 h after intravenous injection of [64Cu]1. The image obtained with coinjection of c(RGDyK) (10 mg/kg body weight) is shown for a 2 h blockade (right). Tumors are indicated by arrows.

Table 2. Decay-Corrected Biodistribution of [64Cu]1 in U87MG Tumor-Bearing Mice Quantified by micoPET Imaging (n = 5)a.

| tissueb | 2 h | 2 h (blockade) | 4 h | 20 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Injected Dose/gram (% ID/g) | ||||

| T | 4.96 ± 0.73 | 0.71 ± 0.30 | 4.11 ± 0.54 | 2.41 ± 0.31 |

| M | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.05 |

| L | 1.76 ± 0.35 | 1.16 ± 0.15 | 1.64 ± 0.23 | 1.25 ± 0.23 |

| K | 2.23 ± 0.21 | 2.09 ± 0.28 | 1.79 ± 0.20 | 0.69 ± 0.26 |

| Tumor-to-Normal Tissue Uptake Ratio | ||||

| T/M | 11.88 ± 1.31 | 2.52 ± 0.81 | 11.65 ± 1.83 | 7.03 ± 1.22 |

| T/L | 2.85 ± 0.28 | 0.60 ± 0.22 | 2.51 ± 0.16 | 1.96 ± 0.26 |

| T/K | 2.22 ± 0.26 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 2.32 ± 0.35 | 3.87 ± 1.26 |

The results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5).

T, tumor; M, muscle; L, liver; K, kidneys.

In conclusion, a new catalyst-free click chemistry approach based on strain-promoted aza-dibenzocyclooctyne ligation has been developed for 64Cu-labeling of biomolecules. In our new approach, we first prepared a 64Cu-labeled alkyne-containing component (prosthetic group), followed by conjugation of biomolecule via click chemistry. Successful employment of catalyst-free click chemistry in the preparation of 64Cu-labeled probes, which was demonstrated in our work, can eliminate the contamination problem of catalyst Cu(I) ions under the conventional Cu-catalyst 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition condition. The strain-promoted click reaction proceeds with a fast rate at low concentration, making it superior to other types of conjugation reactions for radiolabeling with short-lived isotopes, such as 64Cu. Although we focused on the use of integrin αvβ3-specific RGD peptide for proof of principle, the technique is versatile and can be applied to other 64Cu-labeled or other radiometal-labeled probes. More importantly, this new catalyst-free click approach creates a modular platform in which a biomolecule can be modified with a wide variety of chelators and radiometals. Given the fact that different radiometals often require different chelators, this methodology could no doubt assist in the rapid and robust construction of highly diverse radiometalated bioconjugates for in vitro and in vivo screenings, and radioimaging and radiotherapy applications.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PET

positron emission tomography

- CT

computed tomography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- DiAmSar

3,6,10,13,16,19-hexaazabicyclo[6.6.6]eicosane-1,8-diamine

- BFCs

bifunctional chelators

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- pi

postinjection

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures, cell-based integrin αvβ3 receptor binding, and biodistribution data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

2250 Alcazar Street, CSC103, Molecular Imaging Center, Department of Radiology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA.

Author Contributions

§ These authors contributed equally.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the research fund (#IRG-58-007-51) from the American Cancer Society and by the USC Department of Radiology.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Phelps M. E. Positron emission tomography provides molecular imaging of biological processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97169226–9233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambhir S. S. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 29683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Conti P. S. Target-specific delivery of peptide-based probes for PET imaging. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010, 62111005–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ametamey S. M.; Honer M.; Schubiger P. A. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 2008, 10851501–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Chen X. Positron emission tomography imaging of cancer biology: current status and future prospects. Semin. Oncol. 2011, 38170–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller P. W.; Long N. J.; Vilar R.; Gee A. D. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47478998–9033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis B. M.; Lewis J. S. A practical guide to the construction of radiometallated bioconjugates for positron emission tomography. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40236168–6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao G.; Singh A. N.; Oz O. K.; Sun X. Recent advances in copper radiopharmaceuticals. Curr. Radiopharm. 2011, 42109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. T.; Donnelly P. S. Peptide targeted copper-64 radiopharmaceuticals. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 115500–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokeen M.; Anderson C. J. Molecular imaging of cancer with copper-64 radiopharmaceuticals and positron emission tomography (PET). Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 427832–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Sharpless K. B. The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2003, 8241128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlmark A.; Hawker C.; Hult A.; Malkoch M. New methodologies in the construction of dendritic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 382352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallana E.; Riguera R.; Fernandez-Megia E. Reliable and efficient procedures for the conjugation of biomolecules through Huisgen azide-alkyne cycloadditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50388794–8804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J. F.; Zarafshani Z. Efficient construction of therapeutics, bioconjugates, biomaterials and bioactive surfaces using azide-alkyne “click” chemistry. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 609958–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwe K.; Brechbiel M. W. Growing applications of “click chemistry” for bioconjugation in contemporary biomedical research. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2009, 243289–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debets M. F.; van Berkel S. S.; Dommerholt J.; Dirks A. T.; Rutjes F. P.; van Delft F. L. Bioconjugation with strained alkenes and alkynes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 449805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett J. C.; Bertozzi C. R. Cu-free click cycloaddition reactions in chemical biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 3941272–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Verduyn L. S.; Mirfeizi L.; Schoonen A. K.; Dierckx R. A.; Elsinga P. H.; Feringa B. L. Strain-promoted copper-free “click” chemistry for 18F radiolabeling of bombesin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 504711117–11120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Cai H.; Hassink M.; Blackman M. L.; Brown R. C.; Conti P. S.; Fox J. M. Tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene ligation for the rapid construction of 18F labeled probes. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46428043–8045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumhover N. J.; Martin M. E.; Parameswarappa S. G.; Kloepping K. C.; O’Dorisio M. S.; Pigge F. C.; Schultz M. K. Improved synthesis and biological evaluation of chelator-modified alpha-MSH analogs prepared by copper-free click chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21195757–5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis B. M.; Mohindra P.; Weissmann G. I.; Divilov V.; Hilderbrand S. A.; Weissleder R.; Lewis J. S. Modular strategy for the construction of radiometalated antibodies for positron emission tomography based on inverse electron demand Diels-Alder click chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22102048–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Chen X. Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49Suppl 2113S–128S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R.; Beer A. J.; Wang H.; Chen X. Positron emission tomography tracers for imaging angiogenesis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37Suppl 1S86–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. Radiolabeled multimeric cyclic RGD peptides as integrin αvβ3 targeted radiotracers for tumor imaging. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2006, 35472–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubner R.; Wester H. J.; Burkhart F.; Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R.; Weber W.; Goodman S. L.; Kessler H.; Schwaiger M. Glycosylated RGD-containing peptides: tracer for tumor targeting and angiogenesis imaging with improved biokinetics. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 422326–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Sun X.; Niu G.; Ma Y.; Yap L. P.; Hui X.; Wu K.; Fan D.; Conti P. S.; Chen X. Evaluation of 64Cu labeled GX1: A phage display peptide probe for PET imaging of tumor vasculature. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2012, 14196–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H.; Li Z.; Huang C. W.; Shahinian A. H.; Wang H.; Park R.; Conti P. S. Evaluation of copper-64 labeled AmBaSar conjugated cyclic RGD peptide for improved microPET imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 expression. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 2181417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Li Z.; Yap L. P.; Huang C. W.; Park R.; Conti P. S. Efficient preparation and biological evaluation of a novel multivalency bifunctional chelator for 64Cu radiopharmaceuticals. Chemistry 2011, 173710222–10225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. T.; Neels O. C.; Denoyer D.; Roselt P.; Karas J. A.; Scanlon D. B.; White J. M.; Hicks R. J.; Donnelly P. S. Gallium-68 complex of a macrobicyclic cage amine chelator tethered to two integrin-targeting peptides for diagnostic tumor imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22102093–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debets M. F.; van Berkel S. S.; Schoffelen S.; Rutjes F. P.; van Hest J. C.; van Delft F. L. Aza-dibenzocyclooctynes for fast and efficient enzyme PEGylation via copper-free (3 + 2) cycloaddition. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46197–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Hou Y.; Tohme M.; Park R.; Khankaldyyan V.; Gonzales-Gomez I.; Bading J. R.; Laug W. E.; Conti P. S. Pegylated Arg-Gly-Asp peptide: 64Cu labeling and PET imaging of brain tumor αvβ3-integrin expression. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45101776–1783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Li Z. B.; Cai W.; He L.; Chin F. T.; Li F.; Chen X. 18F-labeled mini-PEG spacered RGD dimer (18F-FPRGD2): synthesis and microPET imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34111823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Xiong Z.; Wu Y.; Cai W.; Tseng J. R.; Gambhir S. S.; Chen X. Quantitative PET imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression with 18F-FRGD2. J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 471113–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.