Abstract

Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic receptor via positive allosteric modulation represents an approach to treat the cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease. A series of amides were examined as a replacement for the carboxylic acid moiety in a class of quinolizidinone carboxylic acid M1 muscarinic receptor positive allosteric modulators, and leading pyran 4o and cyclohexane 5c were found to possess good potency and in vivo efficacy.

Keywords: carboxylic acid surrogates, quinolizidinone, positive allosteric modulators

Cholinergic neurons serve critical functions in both the peripheral and the central nervous systems (CNS). Acetylcholine is the key neurotransmitter in these neurons targeting nicotinic and metabotropic (muscarinic) receptors. Muscarinic receptors are class A G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) widely expressed in the CNS. There are five muscarinic subtypes, designated M1–M5,1,2 of which M1 is most highly expressed in the hippocampus, striatum, and cortex,3 implying that it may play a central role in memory and higher brain function.

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the progressive degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain leading to cognitive decline.4 Accordingly, direct activation of the M1 receptor represents an approach to treat the symptoms of AD.5 In this regard, a number of nonselective M1 agonists have shown potential to improve cognitive performance in AD patients but were clinically limited by cholinergic side effects thought to be due to activation of other muscarinic subtypes via binding to the highly conserved orthosteric acetylcholine binding site.6,7

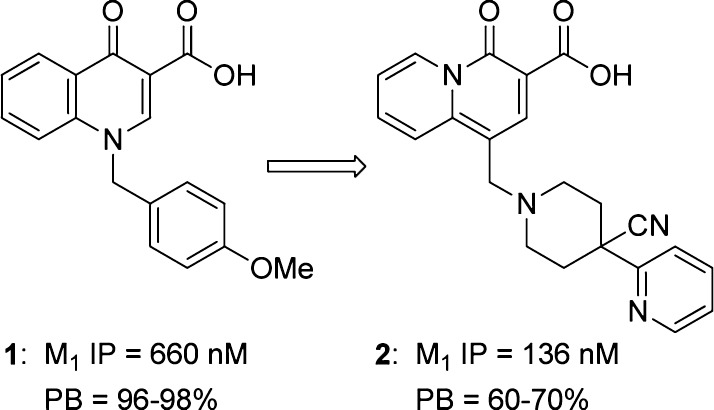

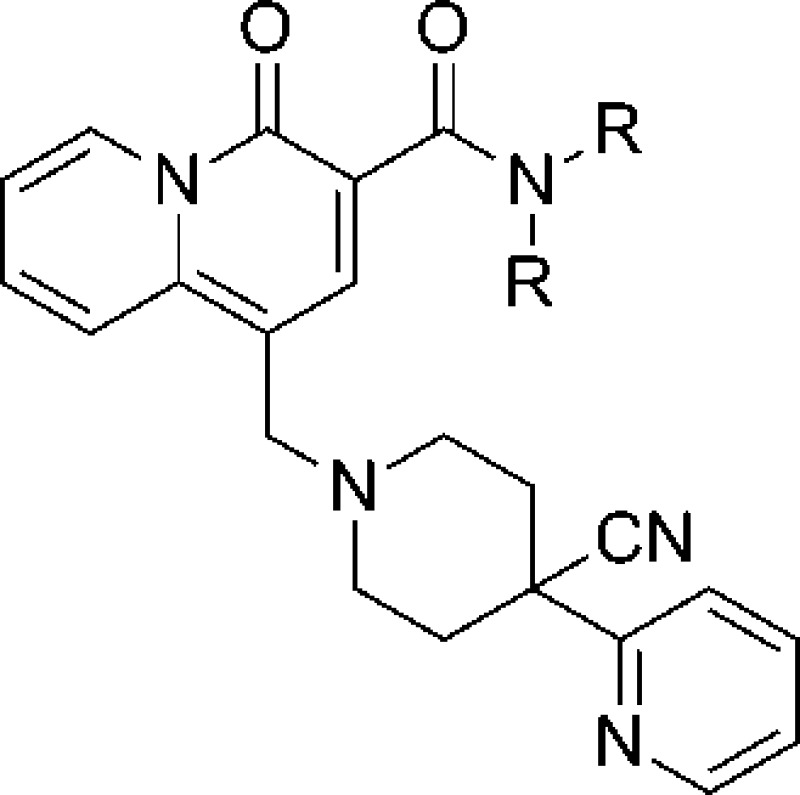

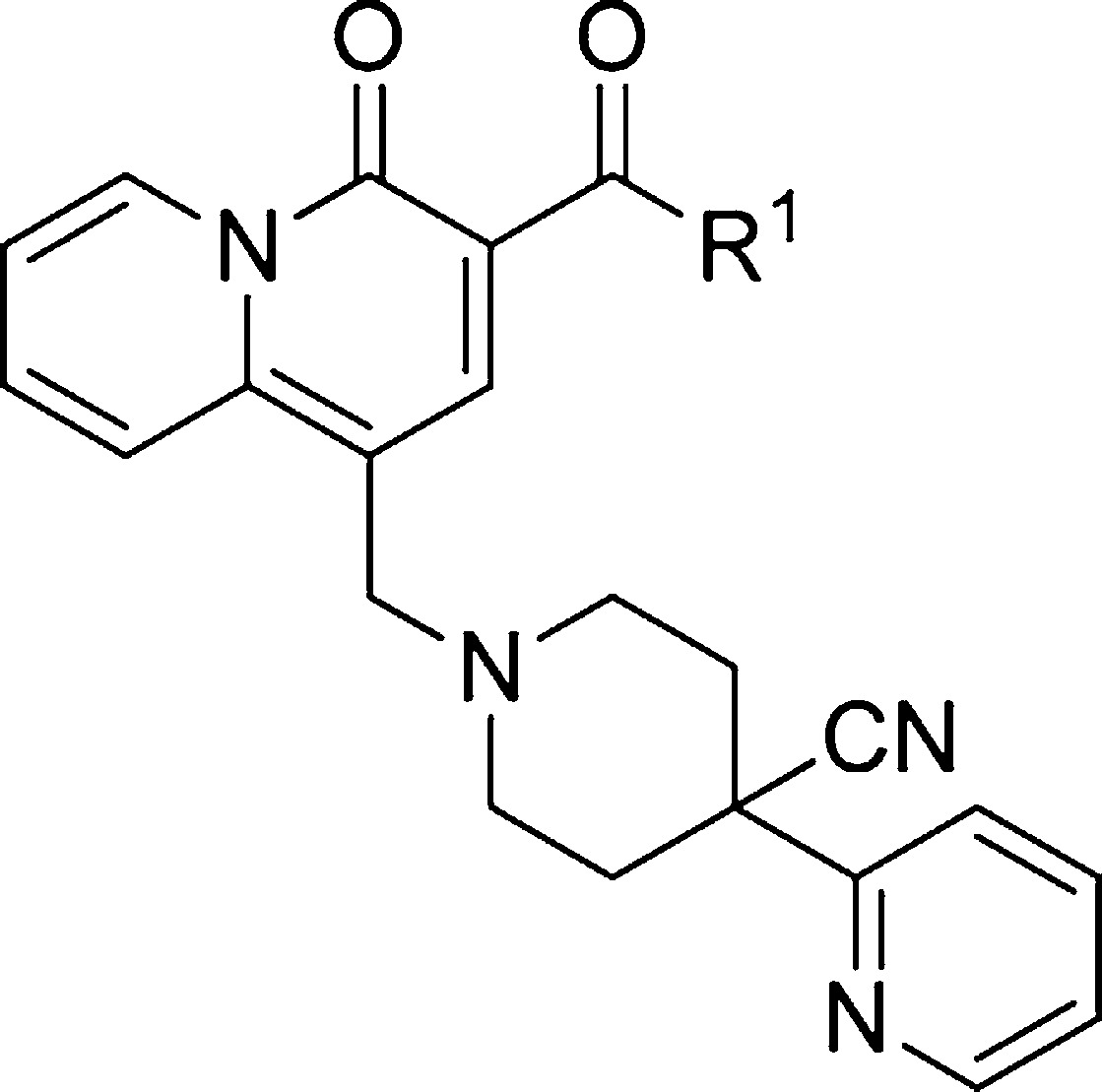

One avenue to engender selectively for M1 over the other muscarinic subtypes is to target allosteric sites on M1 that are less highly conserved than the orthosteric site.8,9 Quinolone carboxylic acid 1 (Figure 1) has been previously identified as a selective positive allosteric modulator of the M1 receptor with exclusive selectivity for the M1 subtype.10 Recent efforts to improve the potency and CNS penetration of 1 led to a number of structural enhancements.11−15 Further advancements were discovered by incorporation of a quinolizidinone ring system such as 2 in lieu of the quinolone, particularly in the area of improved free drug levels and in vivo activity.16−18 However, the presence of the acid in this scaffold limited the extent of CNS exposure, and dominant clearance was by means of direct glucuronidation of the parent acid, complicating human pharmacokinetic predictions. Accordingly, it was of interest to see if noncarboxylic acid M1 potentiators19 could be identified from this acid scaffold. This communication describes efforts to identify CNS penetrant quinolizidinone carboxylic amides as replacements for the acid motif.

Figure 1.

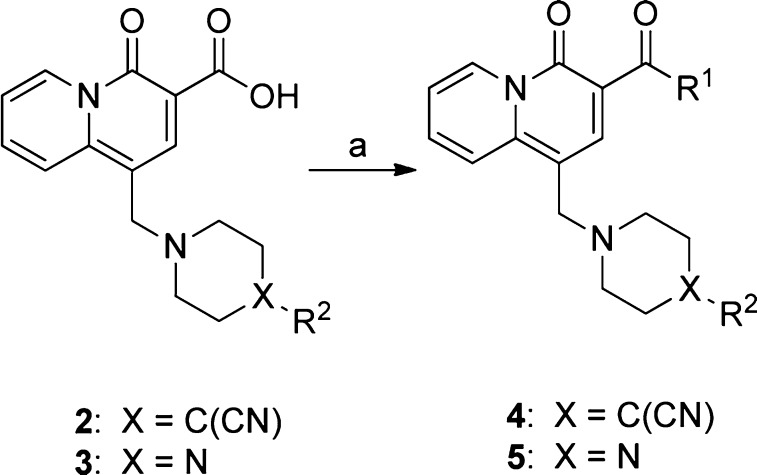

The preparation of requisite amides is shown in Scheme 1. Quinolizidinone carboxylic acids 2 and 3, as well as related analogues, were prepared using previously described procedures.17 Amide bond formation with the appropriate amine using benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (BOP) provided amides 4 and 5.

Scheme 1.

Compound potencies were determined in the presence of an EC20 concentration of acetylcholine at human M1 expressing CHO cells using calcium mobilization readout on a FLIPR384 fluorometric imaging plate reader. A large number of amines were used in library format in Scheme 1 with either 4-cyanopiperidine (2)- or piperazine (3)-linked quinolizidinone carboxylic acids. Select examples are shown in Table 1. Replacement of the acid in 2 with NH2 (4a) led to a >10-fold drop in potency, but at least some activity was preserved. Methylamine (4b) or pyrrolidine (4c) further decreased activity. Several aromatic amines were investigated as represented by 4d–h, with 2-aminopyridine 4h highlighting the most promising among the group.

Table 1. M1 FLIPR Data for Select Compoundsa.

IP, inflection point. Values represent the numerical average of at least two experiments. The interassay variability was ±30% (IP, nM), unless otherwise noted.

While cyclopropyl amide 4i was similarly equipotent to amide 4a, cyclobutane 4j was a submicromolar compound. Increasing the ring size (4k–m) led to an increase in functional activity, with cyclohexyl 4l (M1 IP = 253 nM) being the optimal fit. Insertion of a heteroatom such as oxygen into the cyclohexane ring in the form of a pyran was tolerated, with preference for the 4-position (4o) over the 3-position (4n), while the sulfide analogue (4q) was similarly active. N-Methylation of 4o to tertiary amide 4p lost >10-fold activity, highlighting the requirement for a secondary amide for M1 activity.

Substitution on the cyclohexane ring identified the 2-position in the trans configuration as the most promising. The 2-methyl derivative 4r gave an M1 IP = 190 nM, and similar results were also noted with gem-difluoro 4s. The 2-fluoro derivative is noteworthy as it was similarly equipotent to carboxylic acid 2. Thiomethyl ether 4u was similar to methyl 4r, although methyl ether 4v was less preferred. Moreover, hydroxyl 4w, with the (1S,2S) configuration, was the most potent among the group (M1 IP = 31 nM), ∼4-fold better than acid 2. The associated (1R,2R) enantiomer 4x was ∼7-fold less active. Interestingly, while addition of a methyl at the 2-position of 4w in the form of tertiary alcohol 4y was tolerated, addition of the methyl at the 1-position (4z) led to a complete loss of all M1 activity. It is worth pointing out that select compounds were examined in functional assays at other muscarinic subtypes and showed no activity at M2, M3, or M4 receptors, highlighting that quinolizidinone amides maintain selectivity for M1.

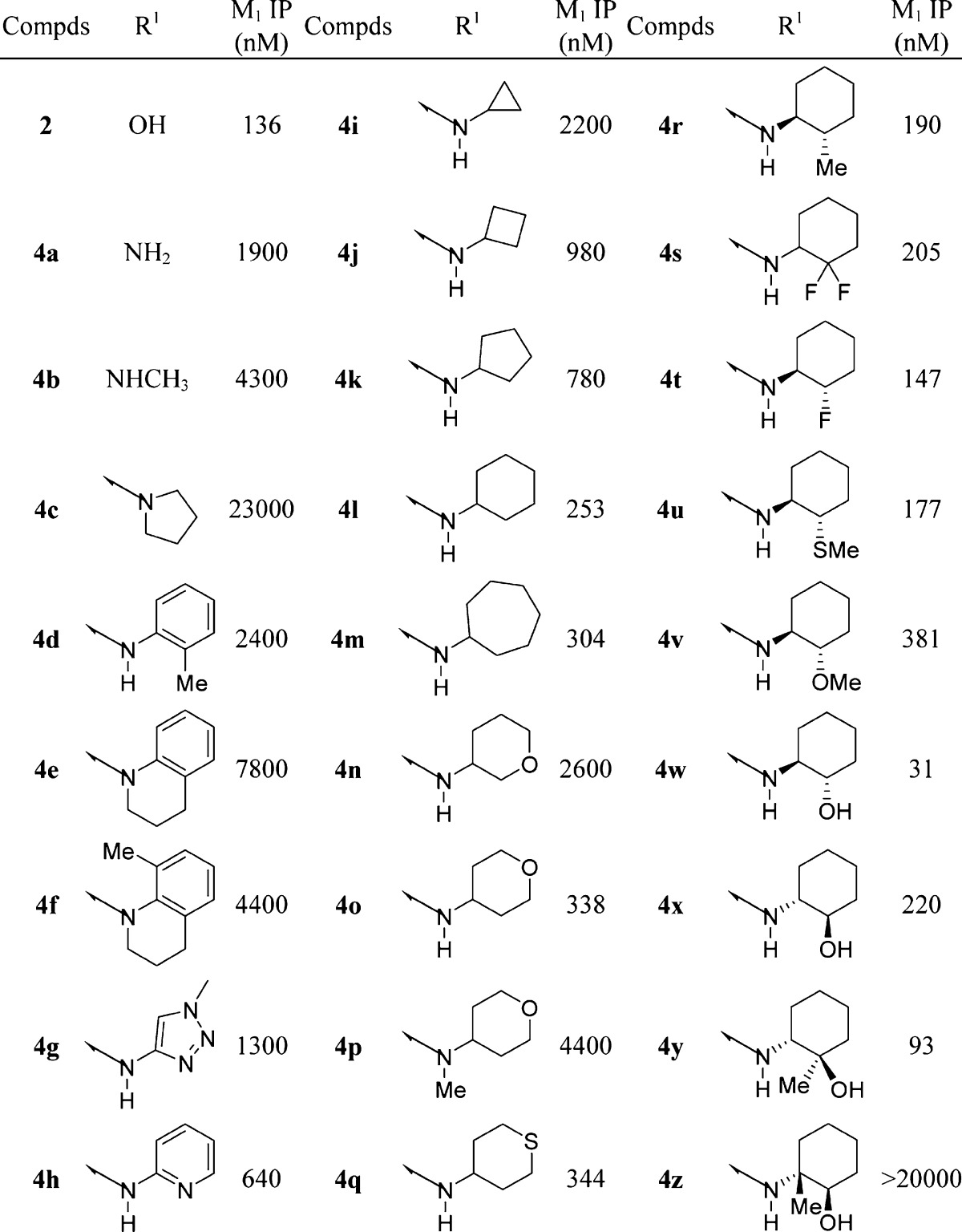

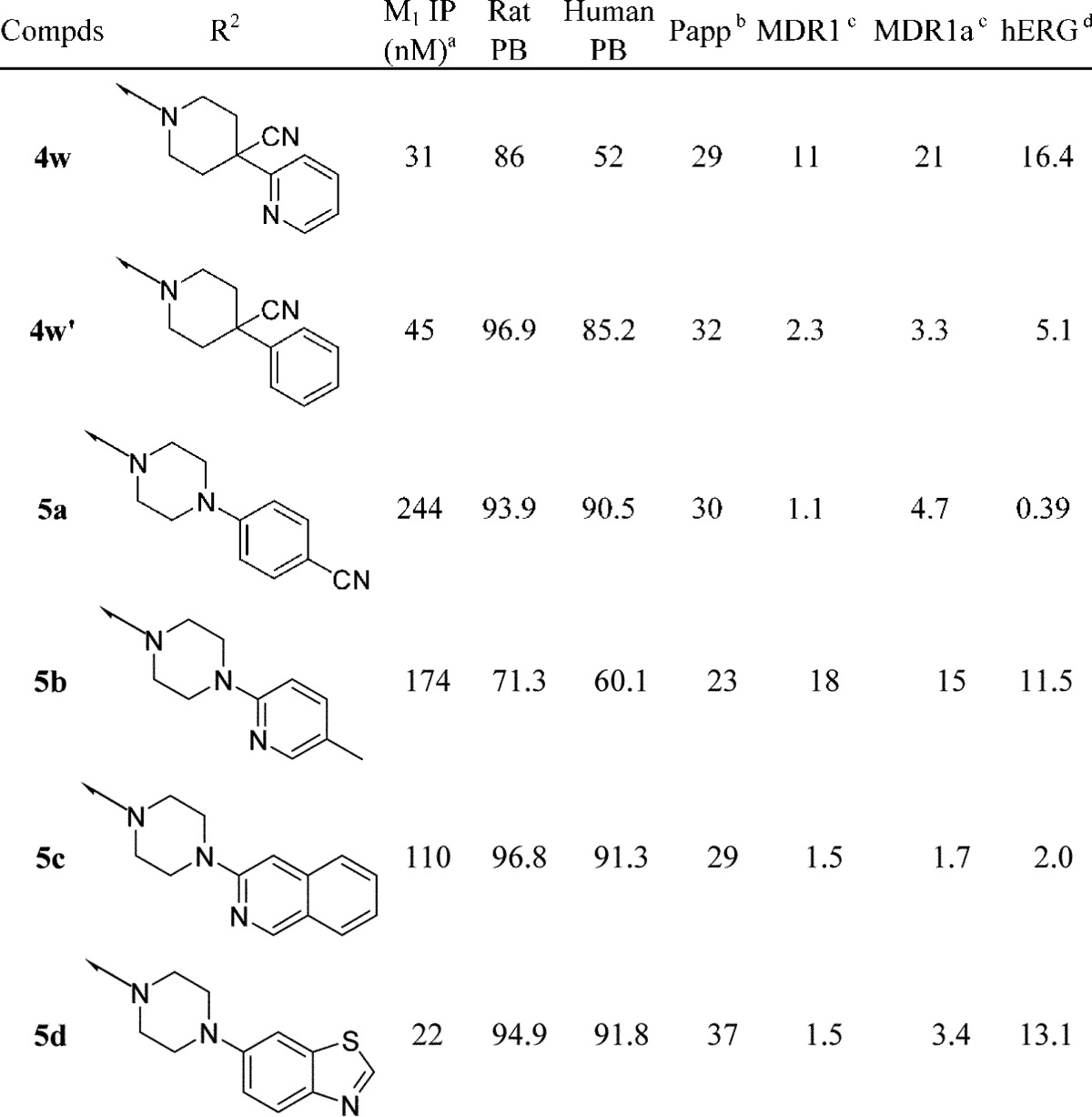

Having identified a number of potent amides, select compounds were examined to see if they were substrates for the multidrug resistant (MDR) efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp). In addition, plasma protein binding was determined using the equilibrium dialysis method in the presence of rat and human serum (Table 2).

Table 2. Protein Binding Data and P-gp Data for Select Compounds.

Passive permeability (10–6 cm/s).

MDR1 (human) and MDR1a (rat) directional transport ratio (B to A)/(A to B). Values represent the average of three experiments, and the interassay variability was ±20%.

Cyclohexane 4l was not a P-gp substrate and exhibited good passive permeability with protein binding in the range of 93–95%. The corresponding pyran analogue 4o increased efflux and was a substrate for rat P-gp (7.5) but showed markedly enhanced free fraction (27 and 49% in rat and human, respectively). Substitution at the 2-position of the cyclohexane with fluorine (4s,t) maintained good permeability and P-gp profiles with improved free fraction relative to cyclohexyl 4l. The most potent potentiator alcohol 4w unfortunately was a substrate for P-gp, as was the tertiary alcohol analogue 4z.

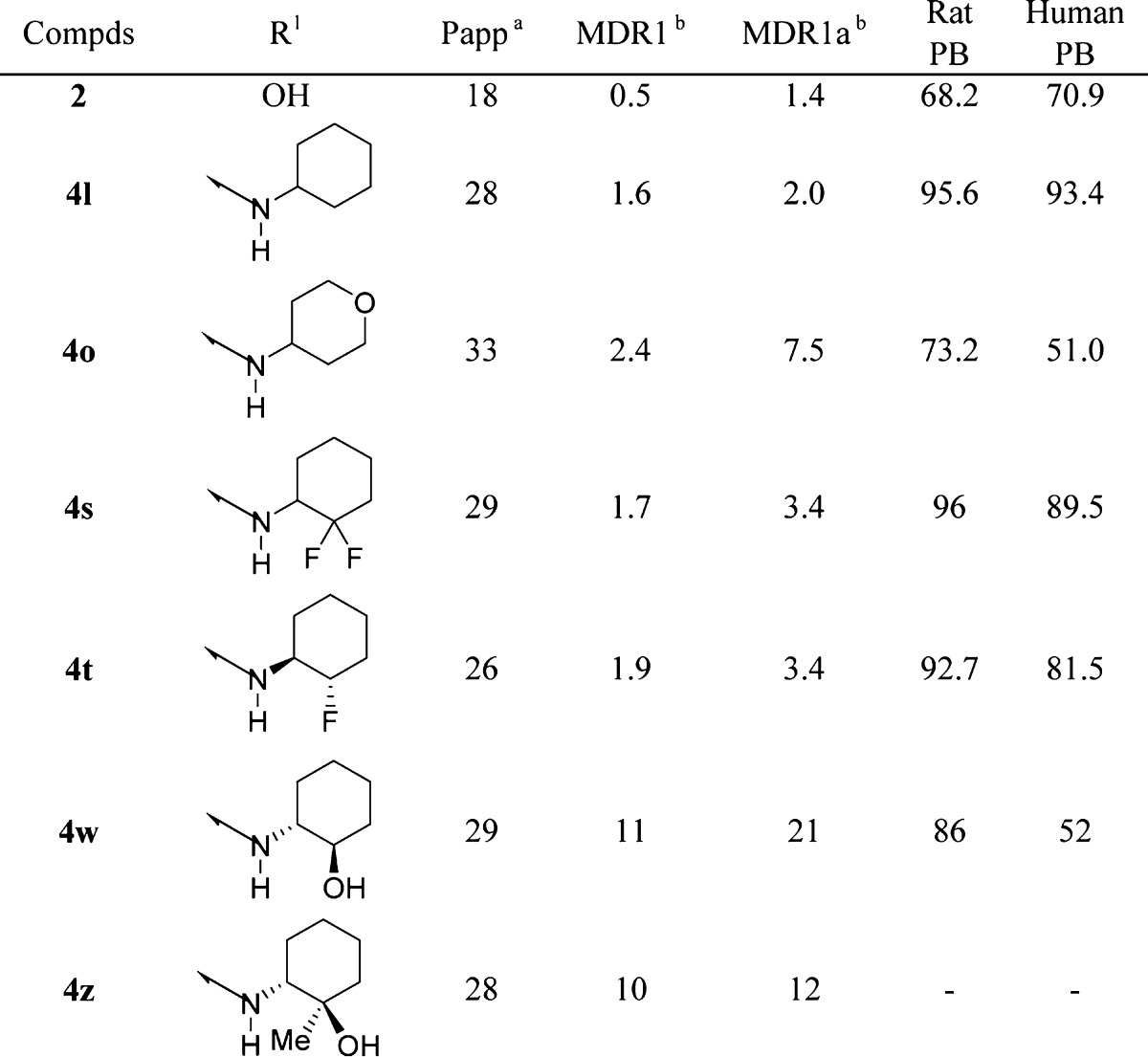

It was thought that the P-gp efflux of highly potent alcohol 4w could be modulated by finding a different amine in place of the 4-cyano-4-(2-pyridyl)piperidine. Replacement of the pyridyl with a phenyl (4w′) led to a modest reduction in M1 potency and free fraction but substantially reduced P-gp efflux. However, this change also led to an increase in human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel binding (IC50 = 5.1 μM), a ∼3-fold increase over pyridyl 4w. Previously in the quinolizidinone carboxylic acid series, aryl piperazine derivatives were identified as potent and CNS penetrant.16 The 4-cyanophenylpiperazine 5a was reasonably potent (M1 IP = 244 nM), with good free fraction, and was not a substrate for P-gp. Unfortunately, hERG binding (IC50 = 0.39 μM) was an issue. Incorporation of a methylpyridine (5b) for the cyanophenyl decreased the hERG binding but markedly increased P-gp efflux. Isoquinoline 5c alleviated the P-gp issues observed with 5b but did so at the expense of higher protein binding. Lastly, benzothioazole 5d represented the most optimized potentiator among the group in terms M1 potency, free fraction, P-gp profile, and hERG binding.

Table 3. M1 FLIPR, Protein Binding, P-gp, and hERG Data for Select Compounds.

Values represent the numerical average of at least two experiments. The interassay variability was ±30% (IP, nM), unless otherwise noted.

Passive permeability (10–6 cm/s) in Madin Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells.

MDR1 directional transport ratio (B to A)/(A to B). Values represent the average of three experiments, and the interassay variability was ±20%.

Values represent the numerical average of at least two experiments. The interassay variability was ±20% (IC50, μM).

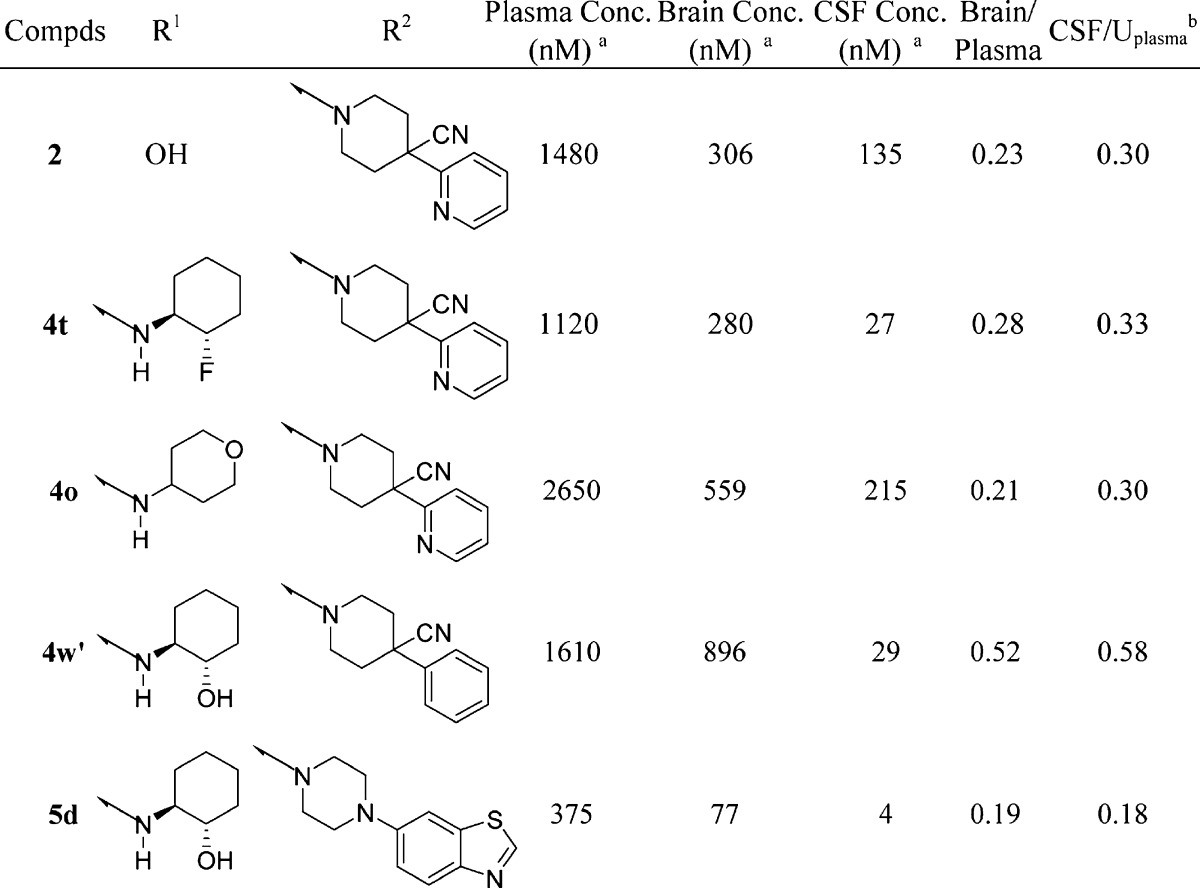

Selected compounds were examined for CNS exposure in rat as shown in Table 4. Brain, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels were measured after 2 h following a 10 mg/kg oral dose. Data for carboxylic acid 2 are shown for comparison.

Table 4. Bioanalysis of Plasma, Brain, and CSF Levels in Rat for Selected Compounds.

Fluorocyclohexane 4t gave a CSF/Uplamsa ratio of 0.33, which was similar to that observed with acid 2, although absolute CSF levels were lower. Pyran 4o gave robust plasma (2.6 μM) and CSF (215 nM) levels, with a comparable CSF/Uplamsa ratio of 0.30. The hydroxycyclohexane 4w′ possessed similar CSF levels to 4t and had the highest total brain levels of the compounds tested. The high CSF level of 4o was believed to be driven by the large free fraction due to the pyran (27%), while all other amides had greater than 90% protein binding. Interestingly, benzothiazole 5d gave very low drug levels in all matrices examined, which was surprising since 5d is not a P-gp substrate, with excellent permeability (Papp = 37) and free fraction similar to other compounds.

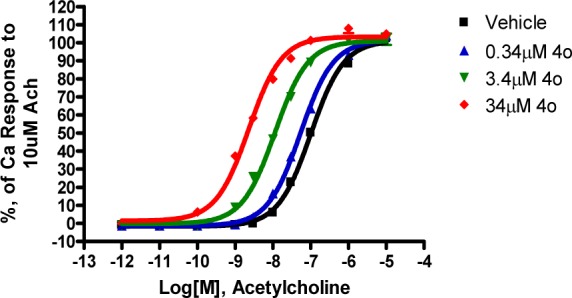

On the basis of the significant CSF levels of pyran 4o, additional studies were conducted to further investigate the properties of amide derived modulators. Fold potentiation with a fixed concentration of modulator 4o was evaluated on the M1 dose response with acetylcholine as the agonist. As can be seen from Figure 2, with increasing concentration of potentiator, a left shift was observed up to 52-fold at 34 μM in the acetylcholine dose response, showing that 4o is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the human M1 receptor.

Figure 2.

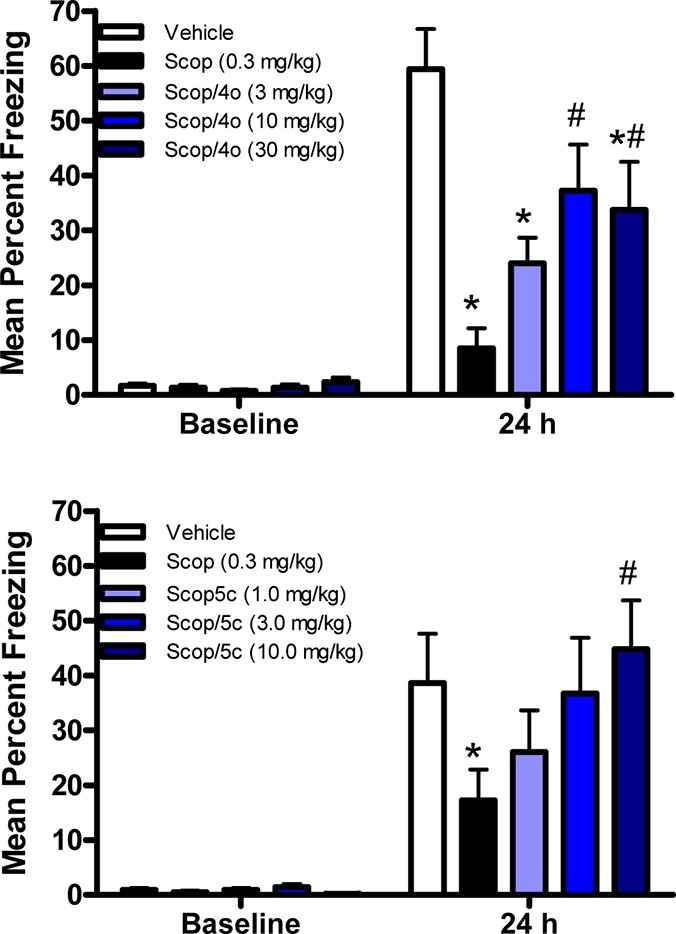

To examine the in vivo properties, amide 4o was evaluated in a mouse contextual fear conditioning (CFC) assay, which serves as a model of episodic memory (Figure 3). In this study, mice were treated with scopolamine before introduction to a novel environment to block a new association. Mice dosed by intraperitoneal injection with 4o exhibited a significant reversal at 10 and 30 mg/kg, as compared to mice treated with scopolamine alone. The corresponding plasma levels at 10 mg/kg were 2.4 μM. By way of comparison, the analogous carboxylic acid 2 showed significant reversal at ∼1 μM plasma levels, which is consistent with greater in vitro potency than 4o in the FLIPR assay. In addition, isoquinoline 5c was also evaluated in mouse CFC and provided full reversal at a very similar plasma level (2.5 μM) to pyran 4o. Accordingly, it appears that amides such as 4o and 5c behave similarly in this rodent cognition model relative to the parent quinolizidinone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators.20

Figure 3.

Evaluation of 4o and 5c in the mouse CFC model.

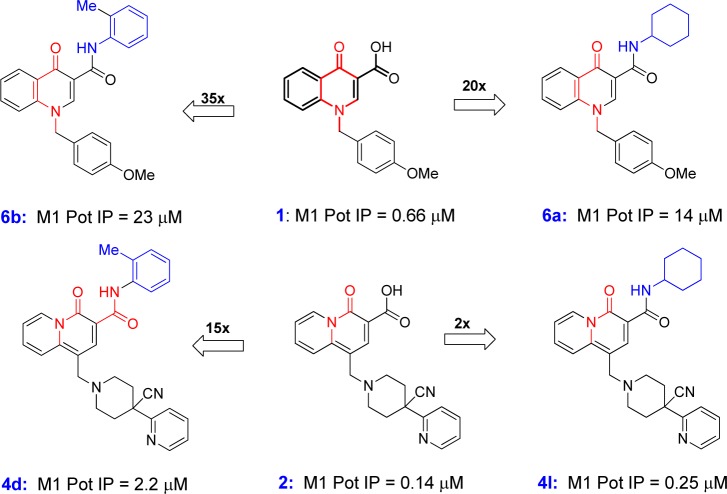

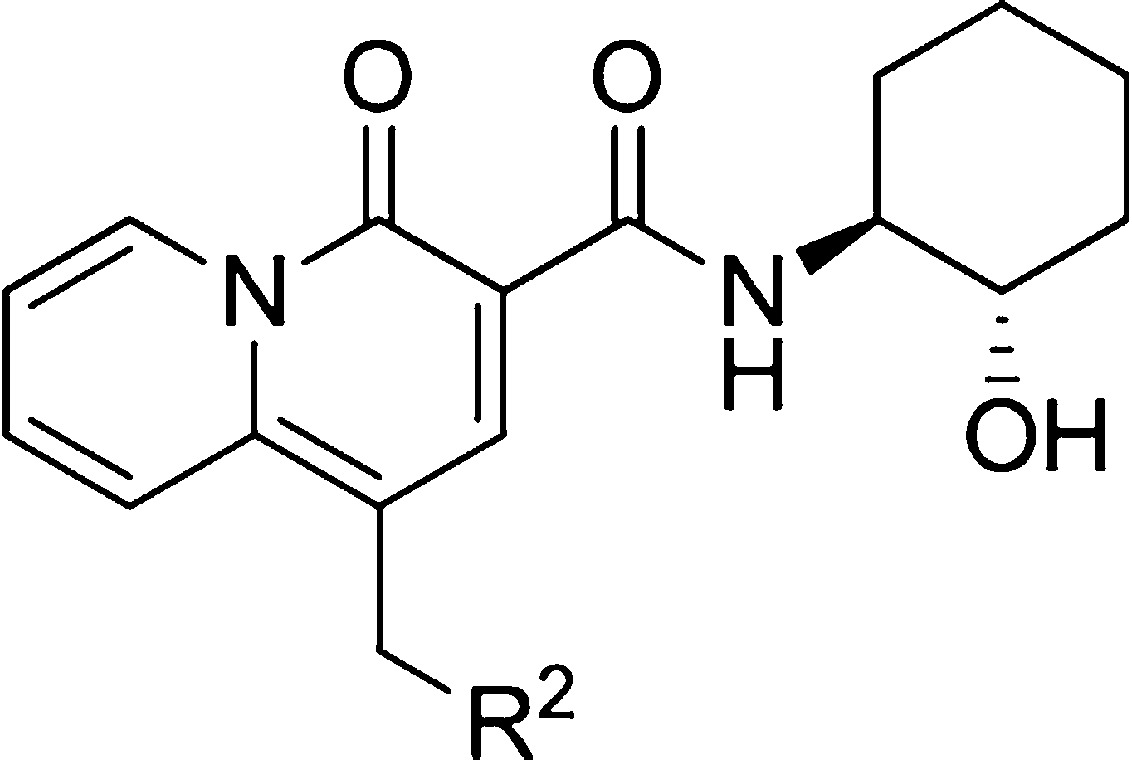

Previously, amides of lead quinolone carboxylic acid 1 have been examined with little success. As can be seen in Figure 4, similar amides made in both the quinolone and the quinolizidinone gave disparate results. For example, while cyclohexyl and tolyl were accommodated in the quinolizidinone context for both 4l and 4d, the quinolone congeners 6a and 6b lost greater than 20-fold potency in the FLIPR assay by way of comparison. Although the exact reason why amides are viable in combination with the quinolizidinone nucleus and not the quinolone is unclear, it serves as another example in which apparently seemingly minor core modifications lead to distinct SAR in allosteric modulator lead optimization.

Figure 4.

In summary, amides of quinolizidinone carboxylic acids were found to be potent and CNS penetrant alternatives as selective M1 positive allosteric modulators. Amides derived from (1S,2S)-2-aminocyclohexanol were found to be markedly the most potent variants but were substrates for the P-gp efflux transporter. Isoquinoline 5c was an exception, which provided efficacy in a mouse contextual fear model of episodic memory but possessed low micromolar hERG channel inhibition. Pyran 4o showed minimal inhibition of hERG (IC50 > 15 μM), was reasonably potent with high CSF levels in rat, and also provided good in vivo activity in mouse CFC. Further optimization of these amides and employment of this strategy in other scaffolds is ongoing.

Supporting Information Available

Representative assay and experimental procedures and data for test compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bonner T. I. The molecular basis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor diversity. Trends Neurosci. 1989, 12, 148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner T. I. Subtypes of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989, 11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey A. I. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression in memory circuits: Implications for treatment of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 13541–13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula C. Abnormalities of neural circuitry in Alzheimer's disease: Hippocampus and cortical innervation. Neurology 1998, 51, 518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead C. J.; Watson J.; Reavill C. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors as CNS drug targets. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 117, 232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodick N. C.; Offen W. W.; Levey A. I.; Cutler N. R.; Gauthier S. G.; Satlin A.; Shannon H. E.; Tollefson G. D.; Rasumussen K.; Bymaster F. P.; Hurley D. J.; Potter W. Z.; Paul. S. M. Effects of Xanomeline, a selective muscarinic receptor agonist, on cognitive function and behavorial symptoms in Alzheimer. Disease. Arch. Neurol. 1997, 54, 465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee W.; Clader J.; Asbersom T.; McCombie S.; Ford J.; Guzik H.; Kozlowski J.; Li S.; Liu C.; Lowe D.; Vice S.; Zhao H.; Zhou G.; Billard W.; Binch H.; Crosby R.; Duffy R.; Lachowicz J.; Coffin V.; Watkins R.; Ruperto V.; Strader C.; Taylor L.; Cox K. Muscarinic agonists and antagonists in the treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Il Farmaco 2001, 56, 247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J.; Christopulos A.; Lindsley C. W. Allosteric modulators of GPCRs: A novel approach for the treatment of CNS. Disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example of an allosteric activator of the M1 receptor, seeJones C. K.; Brady A. E.; Davis A. A.; Xiang Z.; Bubser M.; Noor-Wantawy M.; Kane A. S.; Bridges T. M.; Kennedy J. P.; Bradley S. R.; Peterson T. E.; Ansari M. S.; Baldwin R. M.; Kessler R. M.; Deutch A. Y.; Lah J. J.; Levey A. I.; Lindsley C. W.; Conn P. J. Novel selective allosteric activator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulates amyloid processing and produces antipsychotic-like activity in rats. J. Neurosci. 2008, 41, 10422–10433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Seager M.; Wittmann M.; Jacobsen M.; Bickel D.; Burno M.; Jones K.; Kuzmick-Graufelds V.; Xu G.; Pearson M.; McCampbell A.; Gaspar R.; Shughrue P.; Danziger A.; Regan C.; Flick R.; Garson S.; Doran S.; Kreatsoulas C.; Veng L.; Lindsley C.; Shipe W.; Kuduk S. D.; Sur C.; Kinney G.; Seabrook G.; Ray W. J. Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allosteric potentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 15950–15955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F. V.; Shipe W. D.; Bunda J. L.; Wisnoski D. D.; Zhao Z.; Lindsley C. W.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M. W.; Koeplinger K.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D. Parallel synthesis of N-biaryl quinolone carboxylic acids as selective M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Cofre V.; Pitts D. R.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Pyridine containing M1 positive allosteric modulators with reduced plasma protein binding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Cofre V.; Pitts D. R.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. N-Heterocyclic Derived M1 Positive Allosteric Modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 1334–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Di Marco C. N.; Chang R. K.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Heterocyclic fused pyridone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 2533–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; DiPardo R. M.; Beshore D. C.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Hydroxy cycloalkyl fused pyridone carboxylic acid M1 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 19, 2538–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Identification of Quinolizidinone Carboxylic Acids as CNS Penetrant, Selective M1 Allosteric Muscarinic Receptor Modulators. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 263–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Ray W. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T. Quinolizidinone Carboxylic Acid Selective M1 Allosteric Modulators: SAR in the Piperidine Series. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1710–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuduk S. D.; Chang R. K.; Di Marco C. N.; Pitts D. R.; Greshock T. J.; Ma L.; Wittmann M.; Seager M.; Koeplinger K. A.; Thompson C. D.; Hartman G. D.; Bilodeau M. T.; Ray W. J. Discovery of a Selective Allosteric M1 Receptor Modulator with Suitable Development Properties Based on a Quinolizidinone Carboxylic Acid Scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 13, 4773–4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of noncarboxylic positive allosteric M1 modulators, seeReid P. R.; Bridges T. M.; Sheffler D. A.; Cho H. P.; Lewis L. M.; Days E.; Daniels J. S.; Jones C. K.; Niswender C. M.; Weaver C. D.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Wood M. R. Discovery and optimization of a novel, selective and brain penetrant M1 positive allosteric modulator (PAM): the development of ML169, an MLPCN Probe. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 2697–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In addition, 4o exhibited good preclinical PK properties (dog Cl = 2.8 mL/min/kg, t1/2 = 11 h).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.