On September 16, 2011, President Obama signed the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act into law, which is by far the most comprehensive change to the patent law in at least half a century. Although the impact of the changes in the law will likely not be felt for several years, this law has the potential to fundamentally alter the role of innovation and the status of the researcher within the United States.1

History of Reform

The America Invents Act (“AIA”) is the culmination of a decade long debate on how to “improve patent quality” arising from a series of studies on the relationship of patent law and the larger economy.2 In 2005, Representative Smith of Texas proposed the first version, and between 2005 and 2011, revised patent reform bills were widely criticized by the biopharma and academic sectors and even by the Union of Patent Examiners.3 In 2011, Senator Leahy introduced an amended version of the patent reform legislation, which removed or dampened the most controversial provisions of the law and allowed passage of the AIA.

The AIA

Table 1 provides a comprehensive chart of substantive provisions of the AIA. Those most likely to affect biomedical researchers are: changing from first-to-invent to first-to-file; the new standard for prior art; and postgrant review.

Table 1. Relevant Substantive Provisions of the AIAa.

| §3—“First Inventor to File” | This converts the U.S. patent system from first-to-invent to modified first-to-file. |

| §4—“Inventor's Oath” | This lowers the burden where an inventor is unable or refuses to sign and allows by assignee. |

| §5—Prior User Rights | Prior user defense is broadened for good faith commercial use at least 1 year before filing, with a University Exception. |

| §6—Post-Grant Review and Interpartes review | Post-grant review (PGR) is available within the first 9 months after the patent issues, inter partes review afterward. Both reviews are to be completed within 1 year. PGR can be based on any grounds or on a “novel or unsettled legal question.” Inter partes review is only on prior art patents and publications. The patent owner has an opportunity to amend the claims and provide evidence and comments, and the challenger can file written comments. The challenger must prove unpatentability by a preponderance of the evidence and is precluded in future proceedings from arguing any ground that could have been raised here. |

| §8—3rd Party Submissions | Third parties may submit art to the USPTO, and it will be considered if submitted before the earlier of (1) the date of a notice of allowance or (2) 6 months from publication or first rejection. |

| §12—Supplemental Exam | A postissuance mechanism to cure prosecution defects to avoid charges of inequitable conduct. |

| §15—Best Mode | Failure to disclose best mode is no longer a basis for invalidity, although still required during prosecution. |

| §16—Marking | Marking of products with patent numbers may be virtual. |

| §17—Advice of Counsel | Failure to obtain advice of counsel cannot be used to prove willfulness of infringement. |

| §33—Human organisms | Prohibition of patent claims directed to, or encompassing, human organsms. |

The remaining provisions deal largely with fee setting, venue and jurisdiction, and studies.

First-to-File

Many people think of the AIA primarily as the law that makes the United States a “first-to-file” nation. The United States was unique in its focus on “invention” rather than patent filing.4 Under current law, the first “inventor” is awarded a patent to a new invention, even if someone else was the first to file an application in the matter.5 The relevant statutory section is eliminated in the AIA, although proof of inventorship may still be needed, as it focuses on whether a first filing “inventor” obtained, or could have obtained, the invention from a later filer.6

The AIA adds a new “Derivation” proceeding to allow an inventor on a later-filed patent application to prove that an earlier-filed invention was “derived” from them. The proceedings must be requested within a 1 year time frame and be supported by “substantial evidence”. The USPTO has stated that it will provide guidance on what constitutes “substantial evidence”, but there is concern in the industry that proving derivation is difficult without pre-emptive access to the other party's documents.

Post-Grant Review

Much of the debate around the AIA focused on the new post-grant review provisions. Until now, there were very limited options for a third party to call into question the validity of a patent, but the AIA provides an entirely new period in which anyone can challenge an issued patent on any grounds. Under post-grant review, any party can petition for review of a newly issued patent on any grounds for up to 9 months. After this period, more limited ex- or interpartes review is still available.

Prior Art

One of the most dramatic changes that are instituted in the AIA is the revision of 35 U.S.C §102, which defines what constitutes “prior art” against an invention.7

The most relevant sections of current law state that a person is entitled to an invention unless: (a) prior to the date of invention, it was patented or described in print or known or used by others in the United States;8 or (b) more than 1 year before the filing date, the invention was patented or published by anyone or on sale in the United States.9 The AIA eliminates these provisions and includes as prior art anything that is “patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public” prior the filing date of the claimed invention.10 There is much debate over how the courts will interpret “otherwise available to the public”, but it is generally accepted that this phrase expands the scope of prior art. Importantly, commercial activities are no longer geographically limited to the United States.11

The AIA retains certain protections for researchers, first and foremost a grace period for an inventor's own disclosures. Under the AIA, a disclosure made within 1 year before filing is not prior art if it was made by the inventor or under a joint research agreement,12 or it was made by a third party but the inventor made an earlier public disclosure.13

Implications for Researchers

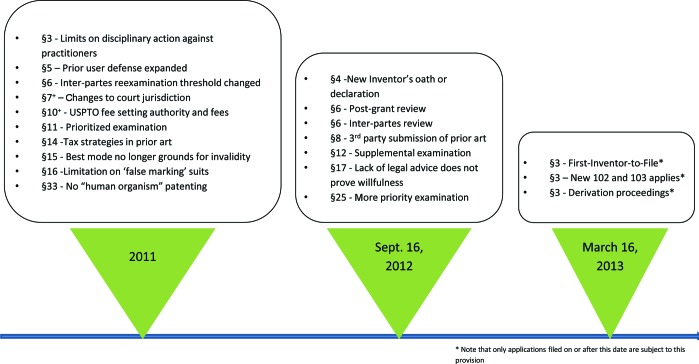

The language of the AIA will require interpretation by the courts, and many provisions do not go into effect immediately and will not be felt for another 3 or 4 years (see Figure 1), making it difficult to predict their effects. However, one principal impact of the AIA on researchers will likely be on document retention. Most researchers are aware of the need to keep and authenticate lab notebooks to support their “invention” but may now also need to keep evidence that another person could have “derived” or obtained an idea from them. Evidence could include tracking conference calls, lab meetings, and other discussions with collaborators. Formal confidentiality agreements and collaboration agreements will also likely become even more important.

Figure 1.

Researchers will also likely feel the impact of post-grant review as it may be more difficult to license early technologies. On the other hand, patents that emerge from post-grant review will be extremely strong and therefore more valuable. In the academic arena, there will be a great deal of interest in the interpretation of “otherwise available” to the public. Would meetings that are currently exempt (such as lab meetings) now qualify? Does treatment of grant applications or paper/abstract submissions change? In addition, some researchers may see a benefit in early publication to eliminate prior art concerns, although less so in the biomedical area.

Overall, the way that the new law will affect researchers remains to be seen. The AIA tasks the USPTO with a number of “reports” (see Table 2), which will allow interest groups, including researchers, an opportunity to provide feedback on implementation. It will be interesting to see how the most controversial provisions are treated and whether fears that biomedical research could be adversely affected emerge as unfounded.

Table 2. Reports Due to Congress.

| report | date due |

|---|---|

| International Protection for Small Businesses Report | January 14, 2012 |

| Prior User Rights Report | January 16, 2012 |

| Genetic Testing Report | June 16, 2012 |

| Effects of First-Inventor-to-File on Small Business Report | September 16, 2012 |

| Patent Litigation Report | September 16, 2012 |

| Report on Misconduct Before the Office Report | September 16, 2013 |

| Open Satellite Offices | September 16, 2014 |

| Virtual Marking Report | September 16, 2014 |

| Satellite Offices Report | September 30, 2014 |

| AIA Implementation Report | September 16, 2015 |

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- The AIA is not the only recent development in patent law that affects the ability of researchers, particularly those in the biomedical arena, to develop new technologies. Over the past decade, the courts have taken on a variety of patent cases that are generally considered to have reduced patent value. Decisions have generally limited the ability of a patentee to go after infringers [see, e.g., eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006), and Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008)]; reduced patent protection during clinical development [see, e.g., Merck KGaA v. Integra Lifesciences I, Ltd., 545 U.S. 193 (2005)]; made it difficult to patent diagnostics [see, e.g., Ass. Molecular Pathology v. U.S.P.T.O., 653 F.3d 1329, 99 USPQ2d 1398 (Fed. Cir. 2011)]; made it more difficult to patent fundamental technologies [see, e.g., Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v Eli Lilly, 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc)]; and made it easier to argue that an invention is obvious [see, e.g., KSR International Co., v. Teleflex Inc. et al., 550 U.S. 398 (2007)].

- See Merrill S., et al. A Patent System for the 21st Century; Committee on Intellectual Property Rights in the Knowledge-Based Economy, National Research Council, National Academy Press: Washington, DC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The opposition focused primarily on three features: a provision limiting damages in patent infringement cases, post-grant revocation proceedings, and a “first-to-file” provision. The bills were heavily supported by high tech but largely opposed by biopharma and academic sectors.

- The AIA has been promoted as a mechanism to conform to international standards.

- The basis for this is current 35 USC §102(g)(2), which provides that a person is “entitled to a patent unless...before such person's invention thereof, the invention was made in this country by another inventor who had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it.”

- Although this may seem pedantic, had Congress taken out the requirement that the person filing have invented the subject matter, it is unlikely that the law would have survived constitutional review. See, for example, Holbrook and Janis letter to Congress, June 13, 2011, http://judiciary.house.gov/issues/Patent%20Reform%20PDFS/holbrook%20janis%20letter.pdf.

- Documents and uses identified under the rules of §102 are used in assessing both novelty under §102 (“was this exact invention disclosed previously”) and obviousness under §103 (“was this obvious to an ordinary person in the art”).

- See current 35 USC §102(a) and (e).

- See current 35 USC §102(b) and (d); current 35 USC §102(c) relates to whether an inventor abandoned his invention, §102(f) relates to whether he stole it from another, and §102(g) provides for interferences if there are multiple independent inventors.

- See amended 35 USC §102(a)(1).

- The law also, for the first time, uses the filing date of a foreign application as its prior art date.

- Or by someone who obtained it directly or indirectly from the inventor.

- See amended 35 USC §102(b).