Context

The landscape of community pharmacy practice is changing rapidly across Canada. New pharmacy service frameworks are being implemented across the country, giving community pharmacists the ability to prescribe, inject medications and provide routine medication reviews.1 With the implementation of new service frameworks, increased emphasis on working within a patient-centred care model and the intensifying need for accessible health care services, community pharmacists are currently facing pressure to shift from “providing products” to “providing patient care services.”2 This shift is supported by existing and emerging technologies as well as regulatory changes that have expanded pharmacists’ scope of practice and allowed pharmacy technicians to play a larger role in dispensing medications.3-5 Still, the majority of patients in community pharmacies see themselves as customers6 and consequently view pharmacists’ main role as provision of medication information rather than clinical services.7 Pharmacists can change this by increasing engagement with patients in order to provide patient-centred care in community pharmacies.8,9 For many pharmacists, the process of actively increasing engagement with patients may require a new understanding of patient-pharmacist relationships and development of new skills.10 The purpose of this article is to introduce the Connect and CARE model to increase pharmacist patient engagement.

Connect and CARE is an evidence-based practice model with affiliated tools that will help community pharmacists shift from a product-centred to a patient-centred practice.11 The evidence for the engagement strategies predominantly arises from the medical literature, including developing rapport,12 agenda setting13 and checking for patient understanding.14 Where possible, evidence was drawn from pharmacy practice research, including the importance of talking to patients at the first refill,15 interactive communication approaches8 and tailoring of medication information.16 This model recognizes that providing patient-centred care requires pharmacists to draw more on their cognitive skills and to increase the time they spend providing patient care services. This requires engagement with patients, and Connect and CARE provides a practical framework for increasing patient engagement. It also identifies teachable skills to enhance the quality of pharmacist-patient engagement. Connect and CARE was built on a thematic review of the literature on patient and pharmacist relationships and was supplemented with evidence collected from individual and group interviews with pharmacists and patients.

Process of Connect and CARE development

Connect and CARE was developed using an applied research approach in 3 overlapping phases. In Phase 1, we consulted with stakeholders across Canada, in addition to reviewing existing evidence on effective pharmacist-patient relationships. In Phase 2, we held focus groups with patients (2 groups comprised of a total of 11 participants) and pharmacists (1 focus group and 3 individual interviews for a total of 8 participants) to ask about their community pharmacy experiences, perceptions of an ideal patient-pharmacist relationship and suggestions for improving existing relationships. Drawing on Phases 1 and 2, we developed an initial pilot model with 5 tools. We solicited feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the draft model and tools through 1 patient focus group with 7 participants and 1 community pharmacist focus group with 4 participants. The model and tools were modified accordingly and then retested with a second set of focus groups (1 patient group with 5 participants and 1 community pharmacist group with 8 participants) and further refined. Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The first 2 authors (LMG and SJ) reviewed the transcripts for themes as well as key quotes.

Participants in both patient and pharmacist focus groups were concerned that many pharmacists may not be ready for change or have sufficient time for patient-centred care. We acknowledged these concerns; our focus was on supporting pharmacists who were ready and willing to change. Furthermore, many pharmacists do not need to take more time with patients but rather need to use existing time with patients more effectively. A few focused minutes can really matter to the quality of engagement and consequent patient care.

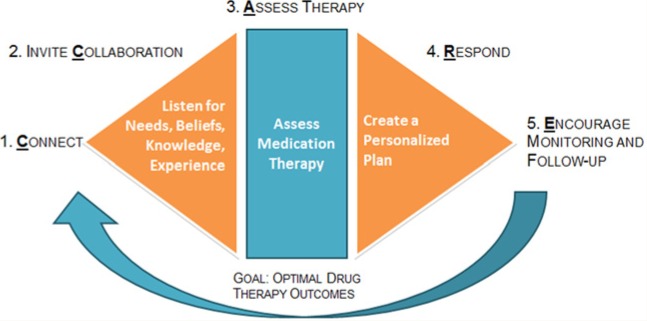

The next section outlines the Connect and CARE model (Figure 1) and related tools (Table 1). Copies of the tools are available on the Blueprint for Pharmacy website.11 We recognize that this model does not work for all practices, nor should a pharmacist use all steps at each interaction. However, we believe that for community pharmacists wanting to shift toward patient-centred care, this model can offer a conceptual framework for change as well as some useful strategies and practical tips for increasing engagement. Finally, we believe that the onus is on pharmacists to be proactive in engaging with patients requiring pharmacy services and, in doing so, to create opportunities for patients to understand and appropriately use community pharmacy services and realize optimal medication therapy outcomes.

Figure 1.

Pharmacists’ Connect and CARE model

Table 1.

Concept models of 5 tools for implementing the Connect and CARE model

| Tool* | Model stage | Purpose | Potential uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pharmacist Reflection | Prior to using model | Provide an opportunity for pharmacists to reflect on their level of patient engagement and satisfaction. | Pharmacists could explore their need and motivation to change their practice. |

| 2. New or Refill Prescription Check† | Collaborate | Identify patients’ questions or concerns about new or refill prescriptions. Inform patients about pharmacists’ services. | Pharmacists or pharmacy staff could distribute this tool to patients or use it with patients. |

| 3. Invite Listen Summarize (ILS) | Collaborate | Allow patients to share their story and allow pharmacists to check their understanding. | Pharmacists could use ILS to open conversations and replace “any questions?” |

| 4. Personalized Medication Information Sheet† | Respond | Produce individually tailored information sheets for patients to use for at-home reference. | Pharmacists could complete and print individual patient information. |

| 5. Patient Quiz: Do you need a med review?† | Respond/encourage follow-up | Provide an opportunity for patients to self-assess their need for a medication review. Initiate conversations about medication reviews. | This tool could be distributed as a handout or bag stuffer. |

Tools are available at www.blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/resource-items/connect-and-care-model-and-tools-interactive_final.pdf.

Tools could be developed as a poster, patient handout, program touch screen tablet mobile device app and/or another format as appropriate for each tool (e.g., Tool 4 could not be a poster).

Connect and CARE Practice

Tool 1 is a brief survey (Table 1) designed to help pharmacists reflect their practice and current level of interest regarding a shift to patient-centred care. Connect and CARE consists of 5 steps that are typically sequential but can be adapted based on the patient-pharmacist interaction.

Connect

Evidence collected showed that patients want to be recognized as individuals, although not all wanted an ongoing relationship with their pharmacist. Patients wanted to feel a connection with the pharmacist during their time together. This was summarized by the patient comment, “It may be only 2 minutes, but you feel support. You don’t feel like you’re just being passed through.”

We identified several strategies to help pharmacists connect with patients: briefly pausing before each patient interaction to focus, introducing themselves, using the patient’s name, taking time for small talk, offering a private area to talk and pausing to let the patient know that the pharmacist has time to talk. For example, “I know it’s hectic around here, but I would like to take 3 minutes to chat to you.” Patients felt it was important to recognize prior encounters if possible: “How has [med name] been working for you this past month?” or “I think you have been in before.” One patient shared, “When I see my pharmacist, he doesn’t say, ‘So, how’s that [med name] working for your migraines?’ He doesn’t, it’s like I’m a whole new person every time I go in.”

Collaborate

In the collaboration stage, the conversation shifts from social talk toward medical or medication issues where patients and pharmacists mutually establish priorities. Pharmacists may “invite” collaboration with the awareness that not all patients will wish to collaborate, but every patient deserves an invitation, ideally from the pharmacist personally. It is important for pharmacists to explain why they are doing this to avoid a negative patient reaction.

Tool 2, the New or Refill Prescription Check (Table 1), provides a structured format to assist pharmacists in identifying patient questions or concerns with new prescriptions or refills. Both include the typical information a pharmacist will provide or ask, as well as additional items that help pharmacists address a patient’s medication needs. To foster collaboration, pharmacists may consider communication techniques such as “Invite Listen Summarize”17 (Tool 3, Table 1) or the “3 prime questions,” where the pharmacist asks an open-ended question to gather information about the purpose, direction and monitoring of a medication.8,18

Assess medication therapy

Patients did not question the quality of pharmacists’ knowledge when they sought advice. Still, to help pharmacists efficiently assess the clinical appropriateness of medication therapy for all patients, community pharmacists may benefit from a systematic thought process. Cipolle et al19 provided 4 concise questions to determine whether a medication is appropriate: Is a medication indicated, effective, safe and manageable for the individual patient? In effect, pharmacists should ask whether this is the right medication therapy for this patient at this time. This assessment of medication appropriateness and the resulting care plan define the key areas in which pharmacists’ roles differ from those of pharmacy technicians.

Respond

In Stage 4, pharmacists can respond with a personalized plan that addresses patients’ needs and preferences. Tool 4, the Personalized Medication Information Sheet (Table 1), was designed to help pharmacists produce patient-specific information. Information should be provided in small chunks, with reference to patients’ understanding of the medication, and time should be taken to check patient understanding.

If a patient would benefit from additional services, this is an opportune time to offer a medication review, injection or other applicable service that specifically meets the patient’s medication needs. Pharmacists are often reluctant to discuss additional patient services they can provide, due to a perception that they may be “up-selling” their services to generate additional revenue. McDonough and Doucette20 document a relationship marketing strategy they have used successfully in community pharmacies, and their relationship marketing approach aligns well with Connect and CARE. For pharmacists not yet comfortable proposing new services, Tool 5 (Table 1) is a Patient Medication Review Quiz, which helps patients self-assess the need for a medication review and start a conversation with their pharmacist.

Encourage monitoring and follow-up

Patients should be aware that pharmacists are interested in their health and want to know how they are doing. It is neither practical nor required for pharmacists to directly contact most patients for follow-up. Still, all patients need to know what to watch for (e.g., benefits and side effects of a medication) in order to accurately assess whether they need help. Pharmacists should let patients know they would like to hear how they are doing: for example, “Drop by next time you are in the pharmacy and let me know how this worked for you.”

Next steps

In presentations to over 100 participants, pharmacists have provided positive feedback on Connect and CARE and found elements that were useful for their individual practices. While elements of the model are evidence based, the use of the Connect and CARE model has not been tested and evaluated in pharmacy practice. If Connect and CARE is to be implemented, the next steps could take place in any or all of the following areas: final development of tools, exploring partnerships for implementation and developing training resources for pharmacists and pharmacy students.

Conclusions

Pharmacist reimbursement frameworks are increasingly shifting from payment for the filling of prescriptions to payment for medication management services, and thus the practice of community pharmacy is moving toward more patient-centred care. Connect and CARE both outlines the unique patient-centred care that community pharmacists offer and illustrates practices for engaging patients in that patient-centred care. ■

Footnotes

Financial acknowledgment:The development of the Connect and CARE Model and tools was funded through a grant from the Blueprint for Pharmacy.

References

- 1. Summary of pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice across Canada. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2014. Available: www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/pharmacy-in-canada/ExpandedScopeChart.pdf (accessed March 11, 2014).

- 2. McPherson TB, Fontane PE. Pharmacists’ social authority to transform community pharmacy practice. Inn Pharm 2011;2(2):Article 42. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lynas K. Ontario leads the country in creating new class of health professional—the pharmacy technician. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2011;144:11 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lynas K. Alberta also moving into pharmacy technician regulation. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2011;144:161 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lynas K. British Columbia becomes second province to register regulated pharmacy technicians with expanded training and scope of practice. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2011;144:155 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perepelkin J. Public opinion of pharmacists and pharmacist prescribing. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2011;144:86-93 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krueger JL, Hermansen-Kobulnicky CJ. Patient perspective of medication information desired and barriers to asking pharmacists questions. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2011;51:510-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guirguis LM. Mixed methods evaluation: pharmacists’ experiences and beliefs toward an interactive communication approach to patient interactions. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:432-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaae S, Nørgaard LS. How to engage experienced medicine users at the counter for a pharmacy-based asthma inhaler service. Int J Pharm Pract 2012;20:99-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blackburn J, Fedoruk C, Wells B. Documenting innovative pharmacy practice in Canada 2007. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2008;141:275 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Secretariat for the Blueprint for Pharmacy National Coordinating Office. Connect and CARE model and tools. Available: www.blueprintforpharmacy.ca/docs/resource-items/connect-and-care-model-and-tools-interactive_final.pdf (accessed Oct. 16, 2013).

- 12. Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract 2002;15:25-38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barrier PA, Li JT, Jensen NM. Two words to improve physician-patient communication: what else? Mayo Clin Proc 2003;78:211-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller MJ, DeWitt JE, McCleeary EM, O’Keefe KJ. Application of the cloze procedure to evaluate comprehension and demonstrate rewriting of pharmacy educational materials. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:650-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hugtenburg JG, Blom AT, Gopie CT, Beckeringh JJ. Communicating with patients the second time they present their prescription at the pharmacy: discovering patients’ drug-related problems. Pharm World Sci 2004;26:328-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dickinson R, Hamrosi K, Knapp P, et al. Suits you? A qualitative study exploring preferences regarding the tailoring of consumer medicines information. Int J Pharm Pract 2013;21:207-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyle D, Dwinnell B, Platt F. Invite, listen, and summarize: a patient-centered communication technique. Acad Med 2005;80:29-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pharmacist-patient consultation program (PPCP-1): an interactive approach to patient consultation. New York: Pfizer; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: the patient-centered approach to medication management. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDonough RP, Doucette WR. Using personal selling skills to promote pharmacy services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2003;43:363-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]