Abstract

The population of the lone star tick Amblyomma americanum has expanded in North America over the last several decades. It is known to be an aggressive and nondiscriminatory biter and is by far the most common human-biting tick encountered in Virginia. Few studies of human pathogen prevalence in ticks have been conducted in our state since the mid-twentieth century. We developed a six-plex real-time PCR assay to detect three Ehrlichia species (E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and Panola Mountain Ehrlichia) and three spotted fever group Rickettsiae (SFGR; R. amblyommii, R. parkeri, and R. rickettsii) and used it to test A. americanum from around the state. Our studies revealed a presence of all three Ehrlichia species (0–24.5%) and a high prevalence (50–80%) of R. amblyommii, a presumptively nonpathogenic SFGR, in all regions surveyed. R. parkeri, previously only detected in Virginia's Amblyomma maculatum ticks, was found in A. americanum in several surveyed areas within two regions having established A. maculatum populations. R. rickettsii was not found in any sample tested. Our study provides the first state-wide screening of A. americanum ticks in recent history and indicates that human exposure to R. amblyommii and to Ehrlichiae may be common. The high prevalence of R. amblyommii, serological cross-reactivity of all SFGR members, and the apparent rarity of R. rickettsii in human biting ticks across the eastern United States suggest that clinical cases of tick-borne disease, including ehrlichiosis, may be commonly misdiagnosed as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and that suspicion of other SFGR as well as Ehrlichia should be increased. These data may be of relevance to other regions where A. americanum is prevalent.

Key Words: : Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, Ticks, Real-time RT-PCR, Vector borne

Introduction

Virginia is a state with diverse and changing tick-borne disease epidemiology that includes human ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), Tidewater spotted fever (an illness caused by Rickettsia parkeri; Wright et al. 2011), Lyme disease, and anaplasmosis. The lone star tick Amblyomma americanum, the most common tick to bite people in the southeastern United States, is increasingly a cause of disease transmission (Paddock and Yabsley 2007, Apperson et al. 2008, Smith et al. 2010, Stromdahl and Hickling 2012), and is likely among the most important arthropod vectors of disease to humans in Virginia.

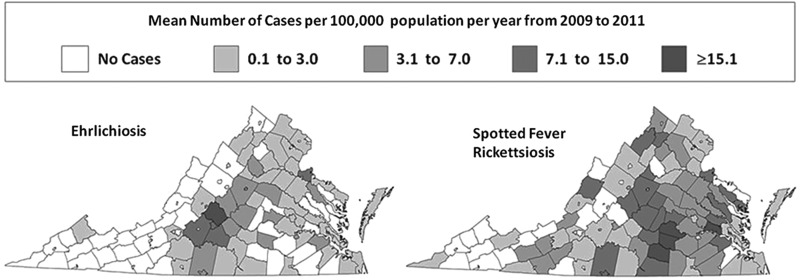

A. americanum potentially transmits ehrlichiosis and rickettsiosis. The case rates of these diseases vary across Virginia (Fig. 1). Human ehrlichiosis attributed to Ehrlichia chaffeensis may cause a mild to fatal illnesses, with a hospitalization rate of 49% and a fatality rate of 1.9% (Dahlgren et al. 2011). Ehrlichiosis caused by E. ewingii is less commonly reported and tends to be associated with previously immune-suppressed patients (Paddock and Yabsley 2007). In 2006, a new Ehrlichia species was discovered in A. americanum in Georgia (Loftis et al. 2006). This new species, known as Panola Mountain Ehrlichia (PME), was subsequently associated with human illness (Reeves et al. 2008) and has been detected in A. americanum collected from 10 different states, including Virginia (Loftis et al. 2008, Yabsley et al. 2008).

FIG. 1.

Mean number of human cases of ehrlichiosis or spotted fever rickettsiosis in Virginia counties and cities averaged over a 3-year period from 2009–2011.

During the past decade, a number of state health departments in the southeastern United States, including the Virginia Department of Health (VDH), have seen large increases in diagnosed and reported cases of RMSF despite a decline in the mortality rate (i.e., a rise in national incidence from 1.7 to 7 cases per million but decrease in mortality from 2.2% to 0.3%) (Chapman et al. 2006, Openshaw et al. 2010, Virginia Department of Health 2012). The agent of RMSF is Rickettsia rickettsii, and Dermacentor variabilis, the American dog tick, is thought to be the primary vector. However, R. rickettsii has rarely been found in the thousands of D. variabilis tested over the past two decades (Ammerman et al. 2004, Dergousoff et al. 2009, Moncayo et al. 2010, Stromdahl et al. 2011). This leaves open the possibility that A. americanum may play a role as a vector (Stromdahl et al. 2011).

A. americanum is also recognized as an important host of Rickettsia amblyommii, a spotted fever group Rickettsia (SFGR) with no apparent pathogenicity for humans. Mixson et al. (2006) found an R. amblyommii infection rate in adult A. americanum of 41.2% from nine states across the eastern United States. Several recent tick surveys in Virginia also found R. amblyommii to be common in A. americanum, with rates of 26–70% (J.S. and H.G., unpublished data) (Jiang et al. 2010).

Another SFGR potentially transmitted by A. americanum is R. parkeri. Although identified over 50 years ago (Lackman et al. 1949, Lackman et al. 1965), R. parkeri was only recognized as a human pathogen in Virginia in 2002 (Paddock et al. 2004). Since that time, human illness caused by R. parkeri has been identified across the southeastern United States (Paddock et al. 2008). The primary vector of R. parkeri is Amblyomma maculatum, the Gulf Coast tick, with high infection rates (41–43%) in ticks collected in Virginia (Fornadel et al. 2011,Wright et al. 2011). However, R. parkeri has also been detected in adult A. americanum from Tennessee and Georgia (Cohen et al. 2009). R. parkeri can infect A. americanum, be transmitted transstadially and transovarially, and subsequently be transmitted to guinea pigs by feeding A. americanum (Goddard 2003).

Few studies of tick species distribution and human pathogen prevalence have been conducted in Virginia since the mid-twentieth century, when research focused on D. variabilis and R. rickettsii (Sonenshine et al. 1966) and more recent surveys have focused on ticks other than A. americanum (Fornadel et al. 2011, Nadolny et al. 2011, Wright et al. 2011). In the intervening decades, deer populations have increased and have led to the subsequent increase and range expansion of the ticks they host, including A. americanum (Paddock and Yabsley 2007, Virgina Department of Game and Inland Fisheries 2007). To investigate the epidemiological role of A. americanum, we first developed a multiplex real-time PCR assay for Ehrlichiae (E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and PME) and three species of Rickettsiae (R. amblyommii, R. parkeri, and R. rickettsii) that could be applied to tick samples. We then collected tick samples from across the state, tested a total of 2545 nymph and adult A. americanum, and compared these findings with state human disease statistics.

Materials and Methods

Study areas and sample collection

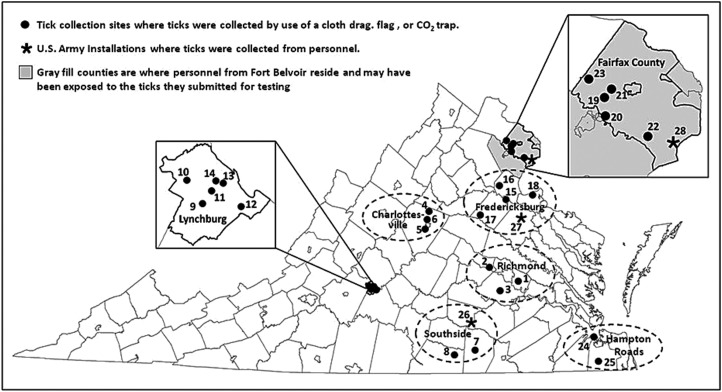

The ticks collected for this study came from the VDH, the Fairfax County Department of Health (FCDH), the Old Dominion University (ODU) Department of Biology, and the US Army Public Health Command (USAPHC). Ticks collected by the VDH were obtained between June 1 and August 15, 2012, by cloth drags, primarily from sample sites at selected municipal, county, or state park lands within each of five survey regions of Virginia, including the Richmond City Area, an area in Southside Virginia, the Charlottesville Area, the Lynchburg Area, and the Fredericksburg Area (Fig. 2). Tick samples were prepared as single adult samples (n=112) or as pooled nymphs (n=1206 nymphs in 388 pools; Table 1). Small pools (two ticks/pool) were created to permit the estimation of infection rates for agents that were likely to be common (i.e., >50% infection rates). Large pools contained up to eight ticks and served to increase the number of ticks tested. Ticks collected by VDH were processed and tested at the University of Virginia (UVA).

FIG. 2.

Amblyomma americanum collection sites across Virginia. Richmond City area: 1, Henrico County; 2, Goochland Co.; 3, Chesterfield Co. Charlottesville area: Sites 4–6, Albemarle Co. Southside Virginia area: 7, Brunswick Co.; 8, Mecklenberg Co., and Site 28, Fort Pickett, Nottoway County. Lynchburg area: Sites 9–14, Lynchburg City. Fredericksburg area: 15, Fredericksburg; 16, Stafford Co.; 17, Spotsylvania Co.; 18, King George Co.; Site 27, Fort A.P Hill, Caroline Co.; Fairfax County Sites 19–23 and Site 28, Fort Belvoir (Fairfax Co. and adjacent counties/cities). Hampton Roads Area: 24, Portsmouth City; 25, Cheaspeake City.

Table 1.

Tick Demographics

| Nymphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total samples tested | Adults | Pools | Total | |

| Richmond Area | 103 | 40 | 63 | 192 |

| Charlottesville Area | 103 | 19 | 84 | 261 |

| Southside Virginia | 102 | 41 | 61 | 194 |

| Lynchburg Area | 100 | 9 | 91 | 284 |

| Fredricksburg Area | 92 | 3 | 89 | 275 |

| Hampton Roads Area | 57 | 45 | 12 | 12 |

| Fairfax Area | 99 | 49 | 50 | 163 |

| US Army Public Health Command | 822 | 370 (351 pools) | 471 | 588 |

| Overall | 1276 | 576 | 871 | 1969 |

Ticks collected by the FCDH were obtained from five sites within Fairfax County (Fig. 2) by means of cloth drags, flags, or CO2-baited traps. Ticks were initially submitted to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) for DNA extraction, and, subsequently, VDH personnel made a random sampling of tick samples collected between June 4 and August 15, 2012, to be sent to UVA for testing. Nymph extracts were pooled (two to nine extracts per pool), while adults were tested as single samples. A total of 49 single adult ticks and 163 nymphs (in 50 pools) were tested (Table 1).

Ticks from ODU were collected by use of drag cloths from March 1 to July 18, 2012, and came from one site in the City of Chesapeake and one in the City of Portsmouth (Fig. 2). Tick specimens were initially extracted at ODU, and included 45 single adult tick extracts and 12 single nymph extracts from 2012 collections (Table 1). ODU also provided tick extracts (24 adults and 18 nymphs) collected from these two sites in 2010 and 2011.

Ticks from the USAPHC were removed from humans at three army installations: Fort Pickett in Southside Virginia, Fort A.P. Hill in the Fredericksburg Area, and Fort Belvoir in Fairfax County (Fig. 2), and submitted to the USAPHC Tick-borne Disease Laboratory, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland for Ehrlichia testing. Ticks from Fort Pickett and Fort A.P. Hill were removed from soldiers training on those installations, whereas ticks from Fort Belvoir were collected from military personnel, civilian employees, and dependents that worked at that installation but lived in the surrounding areas. USAPHC had “superpooled” extracts from the Virginia ticks with tick extracts from installations in other states. USAPHC also maintained extracts of each individual tick so they could be individually retested when a superpool tested positive. Among these pools, a total of 370 adult ticks (351 pools) and 588 nymphs (471 pools) from Virginia, submitted to USAPHC from March 21, 2012 to September 13, 2012, were tested. Because these superpools were not originally tested for SFGR, it was not possible to back trace the original geographic origin of contributing samples whose superpool later tested positive for a SFGR.

DNA extraction

The Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) was used for ticks processed at UVA or at ODU, with some modifications to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, adult ticks (extracted individually) were bisected longitudinally with a razor or surgical blade. Nymphs were extracted individually or in pools. Ticks were placed into 180μL of Buffer ALT and homogenized with glass beads. Samples were centrifuged at 18,000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 30 s at room temperature and placed at 56°C in a dry block. For some samples, an additional 180 μL of Buffer ALT was added followed by the addition of 40 μL of Proteinase K Solution and 6 μL of carrier RNA (1 μg/μL; Qiagen). Samples were placed on the side in a shaker incubator at 56°C for a 1- to 3-h digestion. DNA was isolated using the spin-column protocol for animal tissues, eluted, and stored at −20°C prior to testing by PCR.

At JHSPH, DNA was extracted from individual ticks using a MasterPure DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI), with a modified procedure. Briefly, a tick was placed in Tissue and Cell Lysis Solution, disrupted with a 5-mm stainless steel bead using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen) for 3 min, then centrifuged for 1 min at 16,100 rcf at room temperature in a microcentrifuge. To each sample, 250 μL of Tissue and Cell Lysis Solution containing 1 μL of Proteinase K (50 g/μL) was added. Beads were removed magnetically, and each sample was incubated at 65°C for 60 min followed by a 5-min incubation on ice. DNA was isolated from debris by addition of 150 μL of MPC Protein Precipitation Reagent and centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min at 17,000 rcf. The DNA was then pelleted using isopropanol, air dried, and then resuspended in 30 μL of molecular-grade water.

At USAPHC, genomic tick DNA was extracted by using a Zymo Genomic DNA II Kit™ (Zymo Research Corporation, Orange, California) according to manufacturers' instructions (Stromdahl et al. 2011).

Detection of bacterial DNA by real-time PCR

All multiplex testing for this study was performed at UVA using the Applied Biosystems ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Reactions were performed with Bio-Rad iQ Multiplex Powermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a 25-μL reaction volume with 5 μL of DNA extract. Primers and TaqMan probes (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL) were used at concentrations listed in Table 2. Probes for R. rickettsii and R. amblyommii were adapted from molecular beacon designs. All reactions were run using the following program: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 61°C for 1 min. Each run included a “No template control” (nuclease-free water) and positive controls for each of the six bacterial targets. Postreaction baselines and thresholds were adjusted manually as needed.

Table 2.

Primers and Probes

| Bacterial target | Gene target | Oligo name, type | Sequence, 5′→3′ | Final conc., μM | Amplicon size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. rickettsii | OmpB | RR1370F, F primer | ATAACCCAAGACTCAAACTTTGGTA | 0.4 | 124 bp | Smith et al. 2010 |

| RR1494R, R primer | GCAGTGTTACCGGGATTGCT | 0.4 | ||||

| RR1425B, Probe | FAM-TTAAAGTTCCTAATGCTATAACCCTTACC-BHQ1 | 0.2 | ||||

| R. amblyommii | OmpB | Ra477F, F primer | GGTGCTGCGGCTTCTACATTAG | 0.2 | 141 bp | Smith et al. 2010 |

| Ra618R, R primer | CTGAAACTTGAATAAATCCATTAGTAACAT | 0.2 | ||||

| Ra532P, Probe | HEX-TCCTCTTACACTTGGACAGAATGCT-BHQ2 | 0.2 | ||||

| R. parkeri | OmpB | Rpa129F, F primer | CAAATGTTGCAGTTCCTCTAAA | 0.2 | 96 bp | Jiang et al. 2010 |

| Rpa224R, R primer | AAAACAAACCGTTAAAACTACCG | 0.2 | ||||

| RpaTM-P-TAMRA, Probe | TAMRA-AATTAATACCCTTATGARCASCAGCAG-BHQ2 | 0.2 | This study | |||

| E. chaffeensis/E. ewingii | 16S rRNA | ECH16S-17, F primer | GCGGCAAGCCTAACACATG | 0.4 | 81 bp | Loftis et al. 2003 |

| ECH16S-97, R primer | CCCGTCTGCCACTAACAATTATT | 0.4 | ||||

| E. chaffeensis | 16S rRNA | ECH16S-38, Probe | Texas Red-AGTCGAACGGACAATTGCTTATAACCTTTTGGT-BHQ2 | 0.2 | ||

| E. ewingii | 16S rRNA | EEW16S-97, R primer | CCCGTCTGCCACTAACAACTATC | 0.2 | 83 bp | This study |

| EEW16S-P, Probe | Cy5.5-AGTCGAACGAACAATTCCTAAATAGTCTCTGAC-BHQ2 | 0.4 | This study | |||

| Panola Mountain Ehrlichia | gltA | Ehr3CS-214F, F primer | TGTCATTTCCACAGCATTCTCATC | 0.4 | 145 bp | Loftis et al. 2008 |

| PME344R, R primer | ATTAGCGCAATCATACTTGCAA | 0.4 | This study | |||

| PME266P, Probe | Cy5-TGCCTTAGCTGCACATTATTGTGAT-BHQ2 | 0.2 | This study |

Sequencing of R. parkeri samples

Samples positive for R. parkeri in the multiplex assay were retested by singleplex PCR containing the same R. parkeri primers and probe used in the multiplex. Amplicons from the singleplex were cloned into the PCR 2.1 TOPO vector using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and resulting plasmids were sequenced using GeneWiz (South Plainfield, NJ) or Eurofins MWG Operon DNA sequencing services. Sequence data were compared to the corresponding ompB gene sequence of R. parkeri strain At24 (Genbank EF102239).

Statistics and calculations

Minimum infection rate (MIR) for pooled adults or nymphs is the number of positive pools per total number of pooled nymphs and assumes that each positive pool of nymphs contains only one infected tick. Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) was calculated using a the PooledInfRate, ver. 4.0 add-on to Microsoft Excel (Biggerstaff 2009). MLE calculations are based on the number of pools, pool sizes (number of ticks per pool), and number of positive pools. This calculation provides a 95% confidence interval (CI) on the estimate (Biggerstaff 2008). Adult detection rates by region were compared using the Fisher exact test. All p values were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Test results from ticks collected from the environment by use of dragging or trapping are presented in Tables 3A–C. Test results for ticks collected from personnel on Army Installations are presented in Tables 4A and B.

Table 3A.

Virginia Amblyomma americanum Adults by Survey Regions, Collection Sites and Dates, and Test Results

| Tick collection regions, sites and site numbers | Collection dates | Ticks tested | Ehrlichia chaffeensis % Positive | Ehrlichia ewingii% Positive | Panola Mountain Ehrlichia% Positive | Rickettsia amblyommii % Positive | Rickettsia parkeri % Positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richmond City | 40 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 72.5 | 0 | |

| Henrico Co. (1) | 7/4–6/2012 | 33 | 3.0 | 9.1 | 3.0 | 78.8 | 0 |

| Goochland Co. (2) | 7/11–23/2012 | 6 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 |

| Chesterfield Co. (3) | 7/23/12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Charlottesville | 19 | 0 | 5.3 | 0 | 68.4 | 0 | |

| Albemarle Co. (4) | 6/10 to 7/20/2012 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | 0 |

| Albemarle Co. (5) | 7/19/2012 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Albemarle Co. (6) | 7/19/2012 | 10 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | 80.0 | 0 |

| Southside Virginia | 41 | 0 | 9.8 | 0 | 75.6 | 0 | |

| Brunswick Co. (7) | 7/25/2012 | 38 | 0 | 10.5 | 0 | 79.0 | 0 |

| Mecklenberg Co. (8) | 7/25/2012 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | 0 |

| Lynchburg | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55.6 | 0 | |

| Lynchburg (9) | 7/31/2012 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lynchburg (10) | 7/31/2012 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Lynchburg (11) | 7/31/2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lynchburg (12) | 7/31/2012 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lynchburg (13) | 8/3/2012 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 66.7 | 0 |

| Lynchburg (14) | 8/3/2012 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fredericksburg | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | |

| Fredericksburg (15) | 8/7/2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Stafford Co. (16) | 8/7/2012 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Spotsylvania Co. (17) | 8/15/2012 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| King George Co. (18) | 8/15/2012 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fairfax County | 49 | 24.5* | 14.3 | 6.1 | 81.6 | 2.04 | |

| Fairfax Co. (19) | 6/15–28/2012 | 3 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Fairfax Co. (20) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 50.0 | 100 | 0 |

| Fairfax Co. (21) | 6/7 to 7/11/2012 | 19 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 0 | 57.9 | 0 |

| Fairfax Co. (22) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 11 | 0 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 100 | 9.1 |

| Fairfax Co. (23) | 6/4 to 7/30/2012 | 14 | 28.6 | 0 | 7.1 | 92.9 | 0 |

| Hampton Roads | 45 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0 | 64.4 | 2.2 | |

| Portsmouth (24) | 6/1 to 7/18/2012 | 28 | 3.6 | 3.60 | 0 | 71.4 | 0 |

| Chesapeake (25) | 3/23 to 7/18/2012 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 52.9 | 5.9 |

| Total Across All Sites | 206 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 1.9 | 72.8 | 1.0 |

p<0.05, for detection rate of E. chaffeensis in Fairfax County area vs. Richmond, Charlottesville, Southside, and Hampton Roads areas.

Table 3B.

Virginia Amblyomma americanum Nymphs by Survey Regions, Collection Sites, Collection Dates, and Test Results for Ehrlichia Species

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Ehrlichia ewingii | Panola Mountain Ehrlichia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled nymphs | Pooled nymphs | Pooled nymphs | |||||||||

| MLEb | MLEb | MLEb | |||||||||

| Tick collection regions, sites, and site numbers | Collection dates | Nymphs tested | MIRa% pos. | % pos. | (95% CI) | MIRa% pos. | % pos. | (95% CI) | MIRa% pos. | % pos. | (95% CI) |

| Richmond City | 192 | 3.7 | 3.8 | (1.7–7.4) | 0.5 | 0.5 | (0.0–2.5) | 2.1 | 2.2 | (0.7–5.1 | |

| Henrico Co. (1) | 7/4–6/2012 | 82 | 1.2 | 1.2 | (0.1–5.6) | 1.2 | 1.2 | (0.1–6.0) | 1.2 | 1.2 | (0.1–6.0) |

| Goochland Co. (2) | 7/11–23/2012 | 54 | 1.9 | 1.8 | (0.1–8.4) | 0 | 0 | — | 1.9 | 1.8 | (0.1–8.4) |

| Chesterfield Co. (3) | 7/23/12 | 56 | 8.9 | 10.5 | (4.0–22.3) | 0 | 0 | — | 3.6 | 3.7 | (0.7–11.9) |

| Charlottesville | 261 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.4 | 0.4 | (0.0–1.8) | 0.8 | 0.8 | (0.1–2.5) | |

| Albemarle Co. (4) | 6/10 to 7/20/2012 | 14 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Albemarle Co. (5) | 7/19/2012 | 101 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 2.0 | 2.0 | (0.4–6.2) |

| Albemarle Co. (6) | 7/19/2012 | 146 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.7 | 0.7 | (0.0–3.2) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Southside Virginia | 194 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.5 | 0.5 | (0.0–2.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | (0.2–3.4) | |

| Brunswick Co. (7) | 7/25/2012 | 116 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.9 | 0.9 | (0.0–4.0) | 0.9 | 0.9 | (0.1–4.2) |

| Mecklenberg Co. (8) | 7/25/2012 | 78 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 1.3 | 1.3 | (0.1–5.9) |

| Lynchburg | 284 | 4.9 | 5.3 | (3.1–8.5) | 4.6 | 5.1 | (2.9–8.4) | 2.8 | 3.0 | (1.4–5.6) | |

| Lynchburg (9) | 7/31/2012 | 14 | 7.1 | 8.3 | (0.5–42.6) | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (10) | 7/31/2012 | 82 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 2.4 | 2.6 | (0.5–8.6) |

| Lynchburg (11) | 7/31/2012 | 12 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 25.0 | 27.8 | (8.1–60.6) |

| Lynchburg (12) | 7/31/2012 | 80 | 1.0 | 12.0 | (5.8–21.9) | 11.3 | 15.7 | (7.7–28.7) | 2.5 | 2.6 | (0.5–8.2) |

| Lynchburg (13) | 8/3/2012 | 48 | 8.3 | 8.3 | (3.0–18.2) | 2.1 | 2.2 | (0.1–10.4) | 2.1 | 2.2 | (0.1–10.4) |

| Lynchburg (14) | 8/3/2012 | 48 | 2.1 | 2.0 | (0.1–9.3) | 6.3 | 6.7 | (1.8–17.2) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fredericksburg | 275 | 0.7 | 0.7 | (0.1–2.4) | 0.7 | 0.7 | (0.1–2.3) | 1.5 | 1.5 | (0.5–3.5) | |

| Fredericksburg (15) | 8/7/2012 | 14 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Stafford Co. (16) | 8/7/2012 | 20 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Spotsylvania Co. (17) | 8/15/2012 | 96 | 2.1 | 2.1 | (0.4–6.9) | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| King George Co. (18) | 8/15/2012 | 145 | 0 | 0 | — | 1.4 | 1.4 | (0.3–4.4) | 2.7 | 2.9 | (0.9–6.8) |

| Fairfax County | 163 | 11.6 | 13.4 | (8.7–19.6)* | 4.3 | 4.5 | (2.0–8.7) | 1.2 | 1.3 | (0.2–4.0) | |

| Fairfax Co. (19) | 6/15–28/2012 | 22 | 4.5 | 5.1 | (0.3–25.0) | 9.1 | 8.8 | (1.8–25.3) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fairfax Co. (20) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 28 | 10.7 | 11.4 | (3.3–28.2) | 0 | 0 | — | 3.6 | 3.8 | (0.2–18.4) |

| Fairfax Co. (21) | 6/7 to 7/11/2012 | 41 | 7.3 | 7.2 | (2.1–17.8) | 2.4 | 2.5 | (0.1–10.7) | 2.4 | 2.3 | (0.1–10.7) |

| Fairfax Co. (22) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 38 | 13.2 | 14.0 | (5.8–27.8) | 5.3 | 5.2 | (1.0–15.7) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fairfax Co. (23) | 6/4 to 7/30/2012 | 34 | 20.6 | 28.6 | (14.2–51.6) | 5.9 | 6.4 | (1.2–20.3) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hampton Roads | 12 | 8.3 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Portsmouth (24) | 6/11/2012 | 4 | 25.0 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Chesapeake (25) | 6/4 to 10/15/2012 | 8 | 0 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | – |

| Total across all sites | 1381 | 3.1 | 3.4e | (2.4–4.3) | 1.8 | 1.9 | (1.4–2.7) | 1.6 | 1.6 | (1.1–2.4) | |

MLE estimates for Fairfax County area higher than other regions.

MIR is minimum infection rate for pooled nymphs; number of positive pools per total number of pooled nymphs; assumes that each positive pool of nymphs contains only one infected nymph.

MLE is maximum likelihood estimation from Pooled Infection Rate calculator, Excel add-in; estimates the maximum likely infection rate (%) based on the number of pools, number of ticks per pool, and number of positive pools; provides a 95% confidence interval (CI) on the estimate (Biggerstaff 2009).

Calculation of MLE was not necessary because each tested sample consisted of a single tick.

All pools in this group tested positive, making it impossible to estimate a MLE for the testing outcome.

The calculation for MLE-% positive across sites includes the samples from all sites.

Table 3C.

Virginia Amblyomma americanum Nymphs by Survey Regions, Collection Sites, Collection Dates, and Test Results for Rickettsia Species

| Rickettsia amblyommii | Rickettsia parkeri | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled nymphs | Pooled nymphs | |||||||

| MLEb | MLEb | |||||||

| Tick collection regions, sites, and site numbers | Collection dates | Nymphs tested | MIRa% Pos. | % Pos. | (95% CI) | MIRa% Pos. | % Pos. | (95% CI) |

| Richmond City | 192 | 30.2 | 68.3 | (55.4–80.9) | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Henrico Co. (1) | 7/4–6/2012 | 82 | 29.3 | 67.4 | (47.6–88.6) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Goochland Co. (2) | 7/11–23/2012 | 54 | 29.6 | 61.5 | (39.6–84.3) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Chesterfield Co. (3) | 7/23/12 | 56 | 32.1 | 72.1 | (48.7–94.0) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Charlottesville | 261 | 26.8 | 54.4 | (44.4–65.1) | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Albemarle Co. (4) | 6/10 to 7/20/2012 | 14 | 28.6 | 44.8 | (16.4–87.8) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Albemarle Co. (5) | 7/19/2012 | 101 | 27.7 | 56.1 | (40.3–73.1) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Albemarle Co. (6) | 7/19/2012 | 146 | 26.0 | 53.0 | (39.8–67.4) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Southside Virginia | 194 | 24.7 | 48.4 | (37.3–60.5) | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Brunswick Co. (7) | 7/25/2012 | 116 | 25.0 | 47.9 | (34.2–63.6) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Mecklenberg Co. (8) | 7/25/2012 | 78 | 24.4 | 47.9 | (31.2–67.6) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg | 284 | 24.7 | 46.8 | (37.9–56.6) | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Lynchburg (9) | 7/31/2012 | 14 | 21.4 | 35.8 | (10.4–85.6) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (10) | 7/31/2012 | 82 | 23.2 | 41.9 | (27.2–60.1) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (11) | 7/31/2012 | 12 | 33.3 | 39.9 | (14.8–74.3) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (12) | 7/31/2012 | 80 | 25.0 | 49.1 | (32.5–68.5) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (13) | 8/3/2012 | 48 | 25.0 | 48.4 | (28.0–73.4) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lynchburg (14) | 8/3/2012 | 48 | 25.0 | 48.4 | (28.0–73.4) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fredericksburg | 275 | 27.6 | 57.5 | (47.4–67.9) | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Fredericksburg (15) | 8/7/2012 | 14 | 28.8 | 44.8 | (16.4–87.7) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Stafford Co. (16) | 8/7/2012 | 20 | 20.0 | 28.2 | (9.9–60.8) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Spotsylvania Co. (17) | 8/15/2012 | 96 | 26.0 | 50.4 | (35.1–67.7) | 0 | 0 | — |

| King George Co. (18) | 8/15/2012 | 145 | 29.7 | 70.9 | (55.5–85.6) | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fairfax County | 163 | 28.0 | 64.4 | (49.8–79.8) | 3.7 | 3.8 | (1.6–7.7) | |

| Fairfax Co. (19) | 6/15–28/2012 | 22 | 31.8 | —d | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Fairfax Co. (20) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 28 | 32.1 | —d | — | 3.6 | 3.4 | (0.2–15.5) |

| Fairfax Co. (21) | 6/7 to 7/11/2012 | 41 | 24.4 | 49.9 | (26.7–78.8) | 4.9 | 5.0 | (1.0–15.6) |

| Fairfax Co. (22) | 6/4 to 7/25/2012 | 38 | 26.3 | 49.0 | (26.8–78.6) | 7.9 | 8.1 | (2.3–20.3) |

| Fairfax Co. (23) | 6/4 to 7/30/2012 | 34 | 29.4 | —d | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hampton Roads | 12 | 50.0 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Portsmouth (24) | 6/11/2012 | 4 | 75.0 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Chesapeake (25) | 6/4 to10/15/2012 | 8 | 37.5 | —c | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Total across all sites | 1381 | 27.3 | 55.9e | (51.4–60.5) | 0.4 | 0.4 | (0.2–0.9) | |

MIR is minimum infection rate for pooled nymphs; number of positive pools per total number of pooled nymphs; assumes that each positive pool of nymphs contains only one infected nymph.

MLE is maximum likelihood estimation from Pooled Infection Rate calculator, Excel add-in; Estimates the maximum likely infection rate (%) based on the number of pools, number of ticks per pool, and number of positive pools; provides a 95% confidence interval (CI) on the estimate (Biggerstaff 2009).

Calculation of MLE was not necessary because each tested sample consisted of a single tick.

All pools in this group tested positive, making it impossible to estimate a MLE for the testing outcome.

The calculation for MLE-% positive across sites includes the samples from all sites.

Table 4A.

Amblyomma americanum Adults Submitted to the US Army Public Health Commanda

| Submitting installation | Dates received | Adults tested | Ehrlichia chaffeensis Adult ticks% Positiveb | Ehrlichia ewingii Adult ticks% Positiveb | Panola Mountain EhrlichiaAdult ticks% Positiveb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ft. A. P. Hill | 4/3–7/24, 2012 | 84 | 1.2 | 7.1 | 0 |

| Ft. Belvoir | 3/26–8/21, 2012 | 226 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Ft. Pickett | 5/18–8/21, 2012 | 60 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 0 |

| Total across sites | 370 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 0 |

Data from USAPHC samples is presented separately due to differences in collection methods.

Although some of the adult ticks from each installation pooled, none of the pooled adult samples tested positive, permitting the calculation of infection rates as a percentage of the total number of adult ticks tested.

Table 4B.

Amblyomma americanum Nymphs Submitted to US Army Public Health Commanda

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Ehrlichia ewingii | Panola Mountain Ehrlichia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled nymphs | Pooled nymphs | Pooled nymphs | |||||||||

| MLE | MLE | MLE | |||||||||

| Submitting installation | Dates received | Nymphs tested | MIR % Pos. | % Pos. | (95% CI) | MIR % Pos. | % Pos. | (95% CI) | MIR % Pos. | % Pos. | (95% CI) |

| Ft. A. P. Hill | 3/21–7/24, 2012 | 127 | 0.8 | 0.8 | (0.1–3.8) | 0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | (0.1–3.8) | ||

| Ft. Belvoir | 3/27–9/13, 2012 | 194 | 0.5b | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Ft. Pickett | 5/18–8/21, 2012 | 267 | 1.5 | 1.5 | (0.5–3.6) | 1.5 | 1.5 | (0.5–3.5) | 1.1 | 1.1 | (0.3–3.0) |

| Total across sites | 588 | 0.9 | 1.0c | (0.4–2.1) | 0.5 | 0.7c | (0.2–1.6) | 0.6 | 0.7c | (0.2–1.6) | |

Data from the US Army Public Health Command (USAPHC) samples is presented separately due to differences in collection methods.

Although some of the nymphs from Fort Belvoir pooled, none of the pooled samples tested positive, so the MIR value represents a percentage of the total number of nymphs tested.

The calculation for MLE was % positive across sites includes the samples from all sites.

MIR, minimum infection rate; MLE, maximum likelihood estimation; CI, confidence interval.

Detection of Ehrlichia species

We observed variable E. chaffeensis infection rates in ticks across regions and sites with ranges of 0–24.5% (average 7.3%) in adult ticks and 0–13.4% (average 3.4%) in nymphs. The Charlottesville Area (Table 3A and B) was unique in that E. chaffeensis infection was absent in both nymph and adult ticks at each of the three sites sampled. E. chaffeensis was also absent in the two sites sampled in Southside Virginia, but was detected in a relatively high proportion of ticks from Fort Pickett within that same region. Adult ticks from Fairfax County had a statistically higher rate of E. chaffeensis infection than was seen from any other region (p<0.05, Fisher exact test) (Table 3A and B), but a surprisingly low E. chaffeensis infection rate (0.4% in adult ticks and 0.5% for nymphs) was observed in the ticks collected from Fort Belvoir personnel who resided in Fairfax County and surrounding areas. The geographic distribution of E. ewingii was more uniform, occurring in adult ticks in all regions except for the Lynchburg and Fredericksburg areas, where the numbers of adult ticks tested was relatively low. The E. ewingii detection rate by region ranged from 2.2% to 14.3% for adult ticks (average 7.8%) and 0.4% to 5.1% (average 1.9%) for nymphs (Tables 3A and B). The statewide adult tick infection rate for E. ewingii averaged 7.8%, similar to the 7.3% statewide E. chaffeensis rate. PME was found in adult ticks at sites in only two regions (Fairfax County and the Richmond City Area), but was found in nymphs at all regions except for the Hampton Roads region. Unexpectedly, although rates of PME infection were relatively high in adult and nymph-stage ticks from most sites in Fairfax County, it was not seen in any of the adult or nymph ticks taken from Fort Belvoir personnel who reside in that same region. Compared to E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii, the percentage of PME-positive samples by region was lower, between 2.5% and 6.1% (average 1.9) for adult ticks and 0.8% and 2.8% (average 1.6) for nymphs.

Detection of Rickettsia species

In addition to the three Ehrlichia species, we detected R. amblyommii and R. parkeri (Table 3A and C), but not R. rickettsii. Adult ticks from all regions and all but three sites tested positive for R. amblyommii, and it was found in nymphs from every region and site sampled. R. amblyommii was found in much greater abundance than any bacterial species tested for, with regional detection rates of between 55.6 and 81.6% (average 72.8%) in adult ticks and 46.8 and 68.3% (average 55.9%) in nymphs. Unexpectedly, R. parkeri was found in A. americanum in two regions of Virginia—in the Hampton Roads region and Fairfax County. Additional tick samples from 2010 and 2011 from the Hampton Roads region were tested to determine if the 2012 R. parkeri–positive ticks were a unique finding. R. parkeri was detected in samples from both the previous 2 years, and samples from all 3 years were confirmed for R. parkeri by singleplex PCR and sequence analysis.

Discussion

This bacterial survey in A. americanum ticks represents the first statewide screening of this species in the state of Virginia since the mid-twentieth century (Sonenshine et al. 1966). We developed a multiplex real-time PCR assay for six bacteria of public health relevance and uncovered several findings.

First, the distribution of E. chaffeensis was focal, but where present rates could be relatively high—up to 24.5% in adults and up to 13.4% in nymphs. Across our study, tick infection rates averaged 7.3% in adults and 3.1 % in nymphs. E. ewingii and PME were generally found at lower rates in nymphs but were present at multiple sites in most regions. Therefore, given the preponderance of A. americanum, and its aggressive predilection for biting humans, clinicians in this region should maintain ehrlichiosis high in the differential diagnosis for tick-borne disease. Human ehrlichiosis cases caused by E. chaffeensis have steadily increased in Virginia each year, from 23 cases in 2007 to 130 cases in 2012. This study provides a baseline, whereby future tick surveillance activities could examine whether increases in human illness are paralleled by increases in the tick population and/or its infection rate.

Second, R. amblyommii was found consistently at sites across the state, with regional rates ranging from 56% to 82% of adults and 47% to 68% of nymphs (MLE estimate, Tables 3A and C). In recent years, Virginia has seen substantial increases in RMSF case detection rates. Specifically, in 2010 a total of 145 cases of RMSF were reported, increasing to 231 cases in 2011 and to 461 cases in 2012; these cases are typically reported to health departments by physicians and/or commercial testing laboratories as RMSF, but have been listed under “Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis” in the VDH annual reports since 2011 (Virginia Department of Health 2012). We think it likely that much of this increase in reported RMSF cases is caused by other illnesses, perhaps Ehrlichia, with “false” cross-reacting seropositivity due to the prevalence of R. amblyommii (Apperson et al. 2008, Smith et al. 2010). The rarity of R. rickettsii detection in D. variabilis (Ammerman et al. 2004, Dergousoff et al. 2009, Moncayo et al. 2010, Stromdahl et al. 2011) and its absence in the lone star tick populations we tested further supports this notion and begs the question of what is the RMSF vector? Again, we would advocate for more aggressive consideration of ehrlichiosis in individuals with clinically suggestive tick-borne illness. Of course this distinction does not change treatment (e.g., doxycycline for either), but could greatly affect public health case reporting and more clearly focus the disease prevention message on A. americanum.

We suspect that deer populations are a significant driver of the A. americanum prevalence in Virginia. Virginia deer populations have risen in the last half-century due to several factors, expanding from an estimated 150,000 in the early 1950s, to approximately 422,000 in 1980, to an estimated 945,000 in 2004 (Virgina Department of Game and Inland Fisheries 2007). This expanding population has resulted in some deer becoming adapted to suburban environments, and control efforts in these settings have been largely unsuccessful. The increase in deer has come with an increase in associated ticks, including A. americanum.

A few other findings are worth noting. The discovery of R. parkeri in A. americanum in Virginia was surprising, but strengthens evidence that A. americanum could be a vector. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify this pathogen in multiple A. americanum from each of several regions of within a state. The two regions where these R. parkeri–positive A. americanum ticks were found are the only regions known in Virginia to have established A. maculatum populations, suggesting that A. americanum and A. maculatum share one or more reservoir hosts in these two areas of Virginia. Additional studies will be required to determine the identity of these hosts, assess the extent of host sharing, and determine the shared reservoir host range.

We expected to detect PME within Virginia, but we were surprised to detect it in so many regions of the state. A study by Yabsley et al. demonstrated that PME had entered the Virginia white-tailed deer population as early as 2002 and showed these deer to be a natural reservoir host for PME (Yabsley et al. 2008). PME is not only a disease concern in humans, but in dogs as well (Qurollo et al. 2013).Further surveillance for illness caused by PME is needed to understand its significance as a pathogen.

In sum, we developed a six-plex real-time PCR assay to interrogate bacterial populations within the lone star tick, a vector of substantial increase and public health significance in the state of Virginia. We used the assay in tick populations from around the state, resulting in a substantial detection of Ehrlichia, (including rarely considered species), massive detection of R. amblylommii, and occasional detection of R. parkeri. We advocate use of such methods in the future to track changes in pathogen prevalence in this important tick.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by grant number K25AI067791 to H.G. from the National Institute Of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was also supported by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation to C.W. Support to D.E.N. for this project comes from Fairfax County, Virginia, and support to T.H. comes from NIH grant number T32 AI 007471, the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, and the A. Ralph and Silvia E. Barr Fellowship.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors declare no competing financial interests exist that may create a conflict of interest in connection with this article.

References

- Ammerman NC, Swanson KI, Anderson JM, Schwartz TR, et al. Spotted-fever group Rickettsia in Dermacentor variabilis, Maryland. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:1478–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, et al. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: Is “Rickettsia amblyommii” a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8:597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggerstaff BJ. PooledInfRate, Version 4.0: a Microsoft® Office Excel© Add-in to compute prevalence estimates from pooled samples. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO, USA; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AS, Murphy SM, Demma LJ, Holman RC, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1997–2002. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2006; 6:170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Yabsley MJ, Garrison LE, Freye JD, et al. Rickettsia parkeri in Amblyomma americanum ticks, Tennessee and Georgia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1471–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren FS, Mandel EJ, Krebs JW, Massung RF, et al. Increasing incidence of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in the United States, 2000–2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 85:124–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dergousoff SJ, Gajadhar AJ, Chilton NB. Prevalence of Rickettsia species in Canadian populations of Dermacentor andersoni and D. variabilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:1786–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornadel CM, Zhang X, Smith JD, Paddock CD, et al. High rates of Rickettsia parkeri infection in Gulf Coast ticks (Amblyomma maculatum) and identification of “Candidatus Rickettsia andeanae” from Fairfax County, Virginia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11:1535–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard J. Experimental infection of lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (L.), with Rickettsia parkeri and exposure of guinea pigs to the agent. J Med Entomol 2003; 40:686–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Yarina T, Miller MK, Stromdahl EY, et al. Molecular detection of Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma americanum parasitizing humans. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10:329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackman DB, Parker RR, Gerloff RK. Serological characteristics of a pathogenic rickettsia occurring in Amblyomma maculatum. Public Health Rep 1949; 64:1342–1349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackman DB, Bell EJ, Stoenner HG, Pickens EG. The Rocky Mountain spotted fever group of rickettsias. Health Lab Sci 1965; 2:135–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Massung RF, Levin ML. Quantitative real-time PCR assay for detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2003; 41:3870–3872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Reeves WK, Spurlock JP, Mahan SM, et al. Infection of a goat with a tick-transmitted Ehrlichia from Georgia, U.S.A., that is closely related to Ehrlichia ruminantium. J Vector Ecol 2006; 31:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Mixson TR, Stromdahl EY, Yabsley MJ, et al. Geographic distribution and genetic diversity of the Ehrlichia sp. from Panola Mountain in Amblyomma americanum. BMC Infect Dis 2008; 8:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mixson TR, Campbell SR, Gill JS, Ginsberg HS, et al. Prevalence of Ehrlichia, Borrelia, and Rickettsial agents in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from nine states. J Med Entomol 2006; 43:1261–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, Huang E, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83:653–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadolny RM, Wright CL, Hynes WL, Sonenshine DE, et al. Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) in southeastern Virginia and implications for the spread of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. J Vector Ecol 2011; 36:464–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw JJ, Swerdlow DL, Krebs JW, Holman RC, et al. Rocky mountain spotted fever in the United States, 2000–2007: Interpreting contemporary increases in incidence. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83:174–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Yabsley MJ. Ecological havoc, the rise of white-tailed deer, and the emergence of Amblyomma americanum-associated zoonoses in the United States. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2007; 315:289–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, et al. Rickettsia parkeri: A newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Finley RW, Wright CS, Robinson HN, et al. Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis and its clinical distinction from Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:1188–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qurollo BA, Davenport AC, Sherbert BM, Grindem CB, et al. Infection with Panola Mountain Ehrlichia sp. in a dog with atypical lymphocytes and clonal T-cell expansion. J Vet Intern Med 2013; 27:1251–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WK, Loftis AD, Nicholson WL, Czarkowski AG. The first report of human illness associated with the Panola Mountain Ehrlichia species: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2008; 2:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MP, Ponnusamy L, Jiang J, Ayyash LA, et al. Bacterial pathogens in ixodid ticks from a Piedmont County in North Carolina: Prevalence of rickettsial organisms. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10:939–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine DE, Atwood EL, Lamb JT., Jr.The ecology of ticks transmitting Rocky Mountain spotted fever in a study area in Virginia. Ann Entomol Soc Am 1966; 59:1234–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromdahl EY, Hickling GJ. Beyond Lyme: Aetiology of tick‐borne human diseases with emphasis on the South‐Eastern United States. Zoonoses and Public Health 2012; 59:48–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromdahl EY, Jiang J, Vince M, Richards AL. Infrequency of Rickettsia rickettsii in Dermacentor variabilis removed from humans, with comments on the role of other human-biting ticks associated with spotted fever group Rickettsiae in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11:969–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgina Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Virginia Deer Management Plan 2006–2015. Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Health (VDH). Reportable Disease Surveillance in Virginia, 2012

- Wright CL, Nadolny RM, Jiang J, Richards AL, et al. Rickettsia parkeri in gulf coast ticks, southeastern Virginia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:896–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabsley MJ, Loftis AD, Little SE. Natural and experimental infection of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from the United States with an Ehrlichia sp. closely related to Ehrlichia ruminantium. J Wildl Dis 2008; 44:381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]